Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Fig. 2. Grave 56 from the Luistari cemetery. PHOTOGRAPH BY RAUNO HILANDER 1969. REPRODUCED BY

PERMISSION

.

recognized as ritual offering places used by the

pagan Finnish farmers. In the small depressions, or

cup-marks, cut into large boulders, Finns would

leave offerings of such things as first fruits from the

harvest as a form of thanks to their guardian spirits

and ancestors. Pollen studies from soil cores taken

at Lake Saimaa show that slash-and-burn cultivation

combined with cattle breeding began in southern

Savo in the Late Iron Age. Permanent settlement of

the area does not seem to have taken hold until the

twelfth century. When choosing a dwelling site,

Finns sought out fine soils and a close relation to

bodies of water. It was more important that a site

be suitable for cattle-breeding than for agriculture.

The cemeteries of the Late Iron Age present

much interesting information about trade contacts,

social organization, and religious beliefs including

the process of conversion to Christianity. Finns

practiced both inhumation (burial of the intact

body) and cremation (burning the body) rites. In a

small circumscribed area of western Finland (corre-

sponding to the traditional parishes of Eura, Köyliö,

and Yläne), large inhumation cemeteries—the larg-

est cemeteries of any kind in prehistoric Finland—

have been found (fig. 2). Many of the dead were ac-

companied by rich grave goods, and many of these

items originated from Scandinavia and western Eu-

rope. Males were often buried with impressive sets

of weapons including swords and spears. Both sexes

were often well ornamented with costly brooches,

rings, beads, and other items. Some early-

twentieth-century scholars felt that these people

were too wealthy and foreign-looking in their dress

to be actual Finns, but researchers are now certain

that they were truly Finnish. The explanation seems

FINLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

551

to be that the trade in furs and other valuable goods

that had first stimulated settlement in Ostrobothnia

was now moving into the interior along the Koke-

mäki River. These cemeteries represent the settle-

ments of people who operated the gateway to that

interior route, which perhaps already reached as far

as the Lake Ladoga markets. Such control over valu-

able long-distance trade would indeed make com-

munities in the area wealthy. Perhaps also, because

these Finns dealt so much with foreign traders, they

learned about, and chose to adopt, burial practices

that are strikingly similar to those used nearby in

western Europe. The large inhumation cemeteries

found here remained in use until Christian times.

Their final phases exhibit the effects of conversion.

The latest burials, during the eleventh and twelfth

centuries, are significantly lacking in grave goods

and demonstrate the Christian teaching that the

dead should not take their worldly possessions with

them. When the parishes were finally organized,

these old cemeteries dating from the pagan centu-

ries were abandoned altogether, and new burials

were placed in proper church graveyards.

Although spectacular in the finds they pro-

duced, the western inhumation cemeteries do not

represent the common burial practice of Late Iron

Age Finns. Cremation seems to have been most

common, and cremations could be found both in

mounds and in low-lying stratified, or layered, areas

called field cemeteries. These are unusual in that the

cremated remains are scattered about and inter-

mixed with the remains of other cremated bodies.

All individuality of burial identity is lost by this mix-

ing. This behavior may reflect a prevailing belief in

cyclical reincarnation from a defined ancestral kin

group. Individuals who die lose their former earthly

identity but are eventually transported into a new

earthly form. Thus, the cremation field cemetery

symbolizes the merging of kindred spirits in the af-

terlife.

Other burial types, particularly mound groups,

flourish in different parts of the country. Finland is

a fascinating place to study Iron Age ritual and reli-

gion, for more fragments, both in the ground and

in the folklore, can still be uncovered there than in

other lands with a longer and more deeply en-

grained history of Christianity.

See also Iron Age Finland (vol. 2, part 6); Saami (vol. 2,

part 7); Pre-Viking and Viking Age Sweden (vol. 2,

part 7); Staraya Ladoga (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edgren, Torsten, ed. Fenno-Ugri et Slavi 1988: Papers Pre-

sented by the Participants in the Finnish-Soviet Archaeo-

logical Symposium “Studies in the Material Culture of

the Peoples of Eastern and Northern Europe.” Helsinki:

National Board of Antiquities, 1990. Iskos 9. (Various

papers of interest, including many Iron Age papers.)

———, ed. Fenno-Ugri et Slavi 1983: Papers Presented by the

Participants in the Soviet-Finnish Symposium “Trade,

Exchange and Culture Relations of the Peoples of Fenno-

scandia and Eastern Europe,” 9–13 May 1983. Helsinki:

Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys, 1984. Iskos 4. (Various

papers of interest, including many Iron Age papers.)

Grönlund, E., H. Simola, and P. Uimonen-Simola. “Early

Agriculture in the Eastern Finnish Lake District.” Nor-

wegian Archaeological Review 23 (1990): 79–85.

Hirviluoto, Anna-Liisa. “Finland’s Cultural Ties with the

Kama Region in the Late Iron Age Especially in the

Light of Pottery Finds.” In Traces of the Central Asian

Culture in the North: Finnish-Soviet Joint Scientific Sym-

posium Held in Hanasaari, Espoo, 14–21 January 1985.

Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 194. Edited

by Ildikó Lehtinen, pp. 71–80. Helsinki: Suomalais-

Ugrilainen Seura, 1986.

Huurre, Matti. 9000 Vuotta Suomen Esihistoriaa. Helsinki:

Otava, 1979. (In Finnish.)

Kivikoski, Ella. Die Eisenzeit Finnlands: Bildwerk und Text.

Helsinki: Finnische Altertumsgesellschaft, 1973.

———. Finland. Translated by Alan Binns. London:

Thames and Hudson, 1967.

Lehtosalo-Hilander, Pirkko-Liisa. “Finland.” In From Vi-

king to Crusader: The Scandinavians and Europe 800–

1200. Edited by Else Roesdahl and David M. Wilson,

pp. 62–71. New York: Rizzoli, 1992.

———. Luistari. 3 vols. Helsinki: Suomen Muinaismuis-

toyhdistys, 1982. (Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistyksen

Aikakauskirja 82, nos. 1–3). (A major inhumation

cemetery excavation report in English; burial and arti-

fact catalog in Finnish.)

Meinander, Carl F. “The Finnish Society during the 8th–

12th Centuries.” In Fenno-Ugri et Slavi 1978: Papers

Presented by the Participants the Soviet-Finnish Sympo-

sium “The Cultural Relations between the Peoples and

Countries of the Baltic Area during the Iron Age and the

Early Middle Ages,” 20–23 May 1978. Edited by Carl F.

Meinander, pp. 7–13. Helsinki: Helsinki University,

1980. (Moniste 22).

Odner, Knut. “Saamis (Lapps), Finns and Scandinavians in

History and Prehistory: Ethnic Origins and Ethnic Pro-

cesses in Fenno-Scandinavia.” Norwegian Archaeologi-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

552

ANCIENT EUROPE

cal Review 18 (1985): 1–35. (Determining ethnicity is

a controversial topic.)

Orrman, Eljas. “Geographical Factors in the Spread of Per-

manent Settlement in Parts of Finland and Sweden from

the End of the Iron Age to the Beginning of Modern

Times.” Fennoscandia Archaeologica 8 (1991): 3–21.

Saksa, A. I. “Results and Perspectives of Archaeological

Studies on the Karelian Isthmus.” Fennoscandia Ar-

chaeologica 2 (1985): 37–49.

Shepherd, Deborah J. Funerary Ritual and Symbolism: An

Interdisciplinary Interpretation of Burial Practices in

Late Iron Age Finland. BAR International Series, no.

808. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1999.

Talvio, Tuukka. “Finland’s Place in Viking-Age Relations

between Sweden and the Eastern Baltic/Northern Rus-

sia: The Numismatic Evidence.” Journal of Baltic

Studies 13, no. 3 (fall 1982): 245–255.

Zachrisson, Inger. “Samisk kultur i Finland under

järna˚ldern.” In Suomen Varhaishistoria. Edited by

Kyösti Julku, pp. 652–670. Oulu, Finland: University

of Oulu, 1992.

D

EBORAH J. SHEPHERD

FINLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

553

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

POLAND

■

During the Late Iron Age and Early Middle Ages,

the area that makes up contemporary Poland be-

longed to the outskirts of “civilized” Europe domi-

nated by the Roman Empire. This distant part of the

so-called Barbaricum, however, maintained con-

tacts with the lands at the forefront of cultural de-

velopment. Thus, processes observed in the Ro-

manized parts of the Continent had unavoidable

effects in the area north of the Sudetic and Carpathi-

an Mountains. Because written sources are scarce

and difficult to interpret, one must rely mainly on

archaeological data, with the support of historical

anthropology, to piece together a history of Poland

from the fifth to the tenth century.

In late antiquity the territories to the north of

the Carpathian and Sudetic Mountains faced a seri-

ous socioeconomic crisis. In the fifth and sixth cen-

turies this resulted in a retreat from hierarchical au-

thority and a return to an egalitarian form of

organization. This process was accompanied by a

decrease in widespread exchange, a deterioration of

crafts, a reduction in the assortment of metal prod-

ucts, the disappearance of adornments, and a declin-

ing quality of pottery production. In general, it was

a phase characterized by visible poverty.

This shift might have stemmed from the disrup-

tion of long-distance trade connections. Imported

Roman products played an important role in the

regulation of the social order among the “barbar-

ians” surrounding the Roman Empire. Thus, con-

trol over the nodes of the trade network had the

weight of a political argument because circulation of

prestige objects used for ostentation of status condi-

tioned the sustaining of power relations. Those rela-

tively ranked societies required a steady stream of

supplies from the outside; this made them quite sen-

sitive to changes in contacts with the empire, which

was the main source of status goods. Those contacts

became unpredictable in the wake of the turbulent

geopolitical situation in and around the Roman

Empire in late antiquity. Historians usually blame

this turmoil on the appearance of the Asiatic Huns,

who arrived in the eastern European steppe zone in

A.D. 375 and subsequently installed the center of

their “empire” in the Carpathian Basin. A later

breakdown of the transcontinental communication

network might have caused barbarian elites to leave

distant peripheries in search of closer contacts with

still attractive Roman markets.

SUDDEN CAREER OF THE SLAVS

Such new circumstances resulted in radical changes

in social organization as well as in the archaeologi-

cally observed material culture. The changes dis-

cernible from the sixth century onward cannot be

reliably explained only by the migration of the Slavs,

who settled lands emptied by departed Germanic

populations, for example, the Vandals. It is difficult

to accept the rather common vision of the whole re-

gion between the Vistula and Oder Rivers being

suddenly completely depopulated and then reset-

tled by the Slavic newcomers. These changes, how-

ever, should be viewed from a much broader per-

spective.

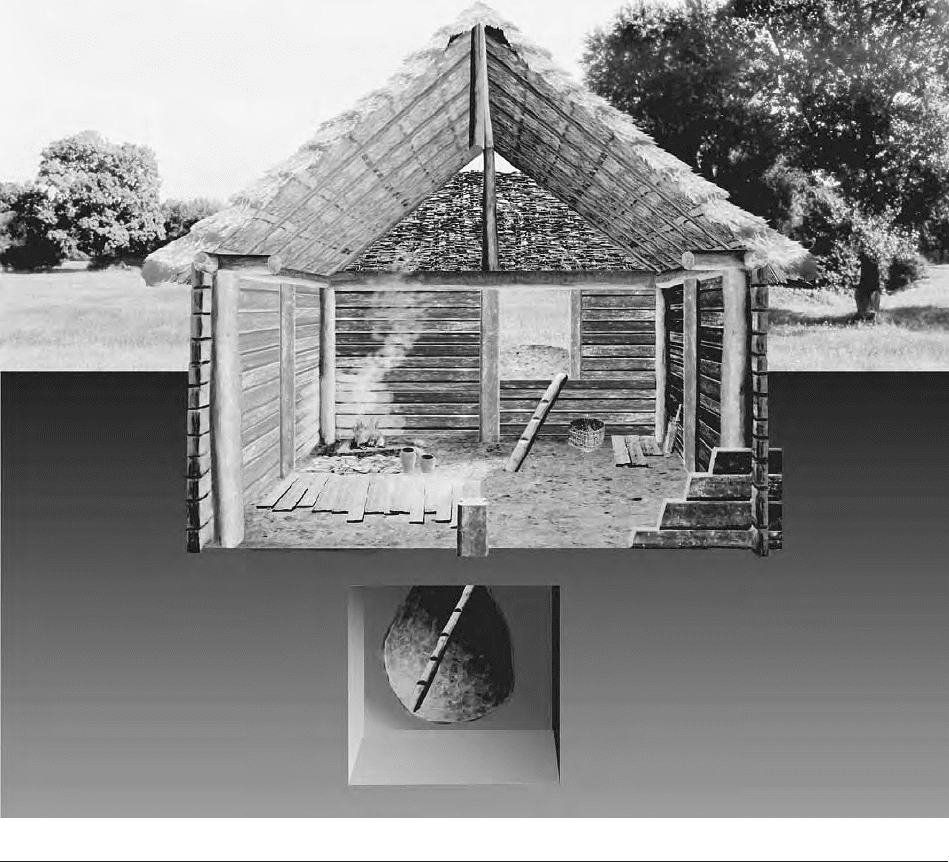

Archaeological data indicate that from the time

of the sixth century, simple societies, based on a

554

ANCIENT EUROPE

nonspecialized, self-sufficient agricultural economy

with an egalitarian power structure, became com-

mon over vast areas of the northern parts of central

Europe. Their uncomplicated socioeconomic orga-

nization is indicated by the layout of their settle-

ments, composed of small houses of a uniform type

(square, sunken huts with stone ovens in one cor-

ner, see figs. 1 and 2) arranged in rows or dispersed

irregularly, as well as by analyses of the cemeteries.

This stage, commonly identified as early Slavonic

culture, was characterized by its small, nondefensive

settlements, poor cemeteries with cremation buri-

als, lack of adornments, and technologically primi-

tive pottery of a uniform shape—the so-called

Prague type. In a rather short time this simple style

of life was adopted by almost all sedentary societies

occupying vast areas of central Europe.

The widespread success of the Slavonic culture,

measured by its spatial expansion, may seem surpris-

ing in light of its poor material equipment and strict

Fig. 1. Example of a Slavic sunken house. COURTESY OF ZBIGNIEW KOBYLIN

´

SKI. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

egalitarianism. Nonetheless, decentralization of the

power structure resulting from a return to the self-

sufficient economy of local farming communities

had the advantage of durability, stability, and pre-

dictability. It was a return to the relationships of sol-

idarity based mainly on kin ties and not on subjuga-

tion (even voluntary) to the interests of military

elites. Studies of spatial patterns of early Slavic set-

tlements indicate a lack of any territorial organiza-

tion, which may suggest that expansion of the Slavs

and the durability of their decentralized ethnicity

were based on the integrative potential of local rural

communities and not on some regional power

structures. During that silent revolution, in the

course of about two centuries, Slavonic culture

came to cover huge areas of the Continent—from

Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany to Thes-

saly in Greece, and from the Ukraine to Bavaria.

This rapid expansion of Slavic culture did not result

from military aggression or a demographic explo-

POLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

555

sion but rather from acceptance of a new lifestyle

that appeared attractive despite its apparent simplic-

ity. It turned out to be economically effective in the

long-term exploitation of various geographic envi-

ronments.

The age-old controversy between supporters of

the “autochthonous,” or indigenous, presence of

Slavs in the vast lowlands between the Oder and

Dnieper Rivers and those who claim that they came

from a small “cradle” located between the Carpathi-

ans and Dnieper cannot be resolved conclusively.

The first group of scholars, stressing continuation of

some elements of “Germanic” material culture and

Fig. 2. A reconstruction of an early Slavic sunken-floored hut (Kraków-Wycia˛z˙ e, Poland). FROM J. POLESKI.

survival of archaic hydronymy is not sensitive

enough to the dynamism of the period of great mi-

grations. Their opponents, who concentrate on the

breakdown of the ancient social structures of the

Barbaricum, overestimate “demographic explo-

sion.” Such an uncompromising opposition of

“continuity” versus “colonization” is false because

both hypotheses are based on radical simplification

of the historical process. Sudden expansion of Slav-

dom cannot be disputed either in cultural terms or

by using demographic categories only, and both as-

pects must be combined. Historical sources, archae-

ological evidence, and linguistic data suggest that

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

556

ANCIENT EUROPE

the spreading of Slavic cultural codes was much

more extensive than the range of the physical migra-

tion of their carriers, who intensively interacted with

locally bound populations. Both processes were

closely interdependent, and it may be impossible to

decide which one was decisive in a given area.

POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT

OF THE SLAVS

The early Slavic self-sufficient agricultural economy

could not supply much of a surplus, which deter-

mined a relatively flat power structure. Apart from

economic constraints, there were also geopolitical

reasons for political retardation of the Slavs. The

most important was the extensive control exerted by

the Avars—Asiatic nomadic warriors who settled in

the Carpathian Basin in 568 and militarily dominat-

ed all of central Europe. It was only after their defeat

by Charlemagne in 799 that dynamic changes

began to be seen among the Slavs. The collapse of

the Avar “empire” and contacts with the mighty

Frankish state, which expanded its tributary zone

toward the east, initiated a lively process of social

hierarchization among the Slavs.

The Polish lowlands had no direct contact with

their mighty eastern Frankish neighbor until the

mid-tenth century. For this reason, the territory

north of the Carpathians did not attract the atten-

tion of early medieval chroniclers. The oldest

source, written c. 848 by the so-called Bavarian Ge-

ographer at the court of the emperor Louis the Ger-

man, offers very vague information, which reflects

little knowledge of the area lying far from the em-

pire’s direct tributary zone. Notes on some mighty

tribes suggest, however, that centralization of polit-

ical power took place there as well. It can be as-

sumed that experience of the long-lasting coopera-

tion with the Avars, the establishment of long-

distance commercial relations, and development of

agrotechnology led, around the mid-ninth century,

to the appearance of local chiefdom organizations

based on redistribution economy. There are various

archaeological indications of such a process.

Great mounds raised in the southeastern Polish

highland in the eighth and ninth centuries (in San-

domierz, Kraków, and Przemys´l) are good indica-

tions of such a process. These monumental earth-

works may be viewed as evidence of attempts to ease

the tensions provoked by growing stratification.

None of these mounds contains a grave, which may

imply that their main function was to materially

manifest the ability to mobilize massive labor input.

The aim was to “hide” the proliferating social differ-

entiation behind the traditional symbolism of a

burial mound. Such actions can be seen as a form

of “propaganda” aimed at social integration despite

the progressive stratification. Big mounds also dis-

play competition for power by men of status who

used them to demonstrate their capacity to mobilize

large groups to act collectively. Thus, they indicate

periods when new elites symbolically marked their

domination.

Arabic written sources address the development

of trade relations with the Muslim world, as does

the inflow of oriental coins that appeared north of

the Carpathian Mountains in three waves during the

course of the ninth and tenth centuries. Slaves were

probably the main export in that period, although

Arabian sources also mention honey, wax, furs, and

amber. These commodities left northern central

Europe either with Scandinavian merchants via the

numerous Baltic trading emporia (e.g., Wolin and

Truso), and later along the eastern European river

system, or by the transcontinental route (from Spain

to Verdun, Mainz, Regensburg, Prague, Kraków,

Kiev, the middle Volga, and Khazaria at the Caspian

Sea coast) served directly by Arab and Jewish mer-

chants.

Apart from the erection of big mounds and the

hiding of silver deposits, archaeological evidence of

a new process of power centralization includes the

building of earth-and-wood strongholds that began

around the mid-ninth century (fig. 3). The strong-

holds indicate a reorganization of the social space

because settlements were concentrated around for-

tified centers, breaking the older network of agricul-

tural settlement into centralized “cells.” As physical

and symbolic centers, they fulfilled an important

role as nodes of social geography. The strongholds

served military functions and were evidence of the

wealth of the ruling elite and its capability to exe-

cute extensive labor expense. Their construction in-

dicated the economic and demographic potential of

the area and might have fulfilled the socially impor-

tant function of uniting a population around a com-

mon goal.

The economic base of a ruling power was sup-

ported by attempts to institutionalize ideology,

POLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

557

which resulted in the organization of cult centers.

Control over these centers was important in sustain-

ing power, because it strengthened political domi-

nation by the sacral legitimization of authority. In

this respect, large regional cult centers located on

“holy” mountains (e.g., S

´

le˛z˙a in Silesia and Łysa

Góra in Little Poland) should be viewed, first of all,

in terms of political struggle.

“CONSTRUCTION” OF THE STATE

The first written evidence of political organization

in Polish lands may be found in the legendary hagi-

ography of St. Methodius, in which “a powerful

prince of Vislech” is mentioned. He used to “ha-

rass” Christian Moravians and subsequently was de-

feated and converted to Christianity between 874

and 880. The traditional interpretation of this ac-

count as a proof of some “state of Vislane” finds no

confirmation in the available data. That “prince”

probably was just one of many regional leaders func-

Fig. 3. Aerial of a small stronghold in Tykocin, Poland. COURTESY OF ZBIGNIEW KOBYLIN

´

SKI. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

tioning around the border of Great Moravia, which

was the main target for looting expeditions.

Despite obvious signs of hierarchization, the

Early Middle Ages were still a time when the process

of power centralization could have been stopped or

even reversed. “Democratic” political institutions

avoided the transition to territorial organizations

ruled by stable monopolistic centers. That “opposi-

tion” had to be broken by ambitious individuals.

Seeking exclusive power, they counteracted egali-

tarian attitudes, while violation of “democratic”

mechanisms often was camouflaged by manipulat-

ing the common tradition. A distant reminiscence

of one such illegitimate takeover of supreme author-

ity is recorded in the dynastic legend of the first rul-

ing Polish dynasty—the Piasts, as cited by the so-

called Gallus Anonymus in the twelfth-century

Cronica Polonorum [Chronicle of the Poles]. The

story relates the expulsion of the ninth-century

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

558

ANCIENT EUROPE

“prince” Popiel because he did not meet the basic

requirements of acceptable leadership.

In the words of Gallus Anonymus, when “the

Polish principality was not yet so large,” Gnezno

was ruled by prince Popiel, who had “many noble-

men and friends.” Once he was not able to “fulfill

the needs of his guests,” meaning he was unable to

give them enough beer and meat; this obligation of

a successful leader was met instead by a simple far-

mer, Piast, whose son Siemowit, “after common ap-

proval,” was elected the prince of Poland. Popiel

was expelled “together with his progeniture.” Sie-

mowit “enlarged the borders of his principality” by

military means, which was continued by his son

Lestek and his grandson Siemomysl. Siemomysl

often used to gather together his “earls and dukes”

and organize sumptuous feasts, at which the prince

asked advice of “the elderly and wise men.” He

ruled unchallenged for many years, and his succes-

sor, Mieszko, also “energetically invaded the neigh-

boring peoples.” “Finally, he demanded to marry

one good Christian woman from Bohemia,” and,

with her help, he “renounced the mistakes of pagan-

ism.”

This is a very good description of the process of

stable territorial state formation, in which military

expansion helped mobilize the whole population

and furnished the economic means to sustain dynas-

tic supremacy. The Piasts were raised to the throne

by disillusioned people. The family managed to

maintain their position thanks to military successes,

which provided material gains and expanded their

domain. The leaders continued to seek the counsel

of the members of the social elite but were, in fact,

beyond their effective control. Mieszko I ultimately

reinforced his power in 966 by conversion to Chris-

tianity, which offered him ideological legitimacy for

unquestioned paramount power.

FOUNDATIONS OF

PRINCELY POWER

From such a perspective one must view not only the

military but also the political and psychological im-

portance of long wars that mobilized and unified

whole societies around victorious chiefs. Wars also

had economic importance because booty supported

the system of redistribution and gift exchange. War

mobilization (against an enemy or for booty) was

the best way to maintain the social order. Most im-

portant, however, war gains (horses, cattle, weap-

ons, slaves, precious metals, and so on) made it pos-

sible to maintain a retinue. Military leadership, even

if temporary, offered very efficient, although short-

term, possibilities of strengthening one’s status. It

also helped limit access to paramount positions to

one privileged family.

Apart from the strategy of reinforcing political

power by military means, it was also necessary to in-

crease the base of economic power by supplement-

ing war income through trade and systematic coer-

cive exploitation of one’s own territory. Thus, the

hundreds of strongholds built by the western Slavs

from the late ninth century onward did not simply

serve military purposes but also were safe places for

staple produce. Those staples came from agricultur-

al surpluses collected from the inhabitants of the

ruler’s own territory. Surpluses were made possible

through the agricultural progress achieved in opti-

mal climatic conditions. The growing role of agri-

culture caused the land to develop into a “commod-

ity” and to become the most important element in

determining the power structure. A class of people

at first controlling and then possessing the land

soon became the main supporters of the state.

Ideological power was strengthened by control

over the ceremonial centers and the rituals celebrat-

ed there as well as by creating an ethnogenetic tradi-

tion. Such a largely legendary tradition was promot-

ed by the privileged elites who, referring to the

Indo-European stereotypes, equaled their genealo-

gy with the origins of their peoples in order to legiti-

mize their dominant position. This was aimed at in-

creasing their power over the people and not over

territory. In the beginning, those people could have

been of many ethnic groups. For this reason, the

monarch needed ideological reinforcement that

would give his people a feeling of unity. Thus, “eth-

nic” identity resulted mainly from relationships with

a specific leader and his family and not from the fact

of living within the same territory or from some

commonly experienced past.

THE ORIGINS OF POLAND

It seems that when a territorial authority and the

control over the religious sphere are turned into a

permanent political center with coercive capability

(an “army”), it is only a step away from becoming

a state. This breakthrough is difficult to discern

POLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

559

from early medieval evidence. For example, the Pol-

ish state of Mieszko I (922?–992) seemed to appear

ex nihilo, because his home area in Great Poland

(Wielkopolska) did not boast any particular concen-

tration of strongholds, no dense settlement, and no

rich cemeteries. In the early tenth century various

areas (Little Poland, Silesia, Great Poland, Masovia,

and Pomerania) showed similar development. Every

one of these regions could have emerged as a small

state. It seems that the main advantage of Great Po-

land was its geographical isolation, which limited

military dangers. Thus, Silesia offered protection

from the direct interventions of the mighty eastern

Frankish empire, Little Poland protected from Rus

aggression, Pomerania absorbed the activity of the

Scandinavian Vikings, and Masovia stood against vi-

olent Prussians. Thus the final success of Great Po-

land was determined greatly by its location, which

enabled the Piast dynasty to win the race for stable

state formation.

Dendrochronological dates indicate a growing

settlement network in Great Poland as late as the

mid-tenth century, when Mieszko’s state already

had entered Continental geopolitics. His strategy

was described in 965/66 by the Spanish Jewish

merchant Ibrahim ibn Jaqub of Tortosa, who re-

ported on his journey to Prague. He noticed the

striking effectiveness of a military model based on

the domination of a professional, heavily armed cav-

alry and the stabilizing effect of the stronghold net-

work. Soon the Polish prince effected an ideological

revolution by accepting Christianity as the new state

religion in 966. All these measures allowed him to

secure unquestionable political domination for him-

self and his descendants.

There must have been a centralized form of co-

ercion applied, under which old kin-based relation-

ships were replaced with new social hierarchy rela-

tionships of political obedience while “democratic”

supervision by the common assembly was replaced

by norms of the imposed royal law. Military power

was applied, which in the core area of the early

Piasts’ state in the mid-tenth century manifested as

the phase of destruction of the old strongholds,

which were replaced by new ones. Those new nodes

of power often were localized at the same site or

nearby the earlier ones.

Mieszko’s state was not yet “Poland.” It was the

state of the Piasts who had executed their dynastic

goals with the support of a military aristocracy. To

Ibrahim ibn Jaqub it was obvious in 965 that it was

the monarch with his retinue who created and rep-

resented the state. Thus he called it “the state of

Mieszko.” It was not until much later, after stable

territorial foundations of dynastic power were laid

down, that it was possible to identify the state not

personally but geographically. It was recorded in

the last quarter of the tenth century, that the name

of the central town (Gniezno) was used for identify-

ing the state ruled by the Piasts. In a document writ-

ten c. 990 and called Dagome iudex (the meaning

of which remains unknown), Mieszko I described

his own domain as civitas Schinesghe/Schignesne,

that is, “the state of Gniezno.” The first coin of his

son Boleslav I (r. 992–1025) makes a similar refer-

ence, written as “Gnezdun civitas.” The general ter-

ritorial name Polonia appeared as late as about

A.D.

1000, when the relatively stable geopolitical struc-

ture of central Europe took shape. It was then that

the need to attain geopolitical legitimacy forced

Boleslav I to introduce a package of commonly ac-

cepted attributes of an independent state, that is, an

archbishopric, coinage, a territorial name, and a

royal crown.

THE REGIONAL POWER

It took three generations of the Piast dynasty to or-

ganize a large, stable, strong state, which came to

dominate central Europe by the turn of the millen-

nium. Dendrochronology indicates that it must

have been Mieszko’s father, Siemomysl, who laid

the foundations of the dynastic domain in central

Great Poland during the fourth and fifth decade of

the tenth century. It was in that period when a net-

work of strongholds was created with centers in

Gniezno, Giecz, Poznan´, Lednica, Moraczewo, and

Grzybowo. They were surrounded by dense systems

of rural settlements. As the first historical ruler,

Mieszko I laid the territorial foundations of the

state, which quickly expanded in all directions.

Growing in power, he had to enter the geopolitical

stage, where he showed skills of an experienced

gambler.

Long unnoticed by the German empire, the

Piast state emerged in the seventh decade of the

tenth century as a military power able to challenge

mighty Bohemian and Hungarian princes. Mieszko

I started a complex game of alliances aimed at rein-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

560

ANCIENT EUROPE