Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Chifflet’s study deserves to be considered the first

truly scientific archaeological publication.

This study has proved all the greater a boon be-

cause most of the original artifacts have disappeared.

The archduke took them home to Vienna when he

retired. Upon his death in 1662 they came into the

possession of Leopold I, emperor of Austria, who,

in 1665, sent them to France as a diplomatic present

to young King Louis XIV. The collection survived

the French Revolution intact, but one night in 1831

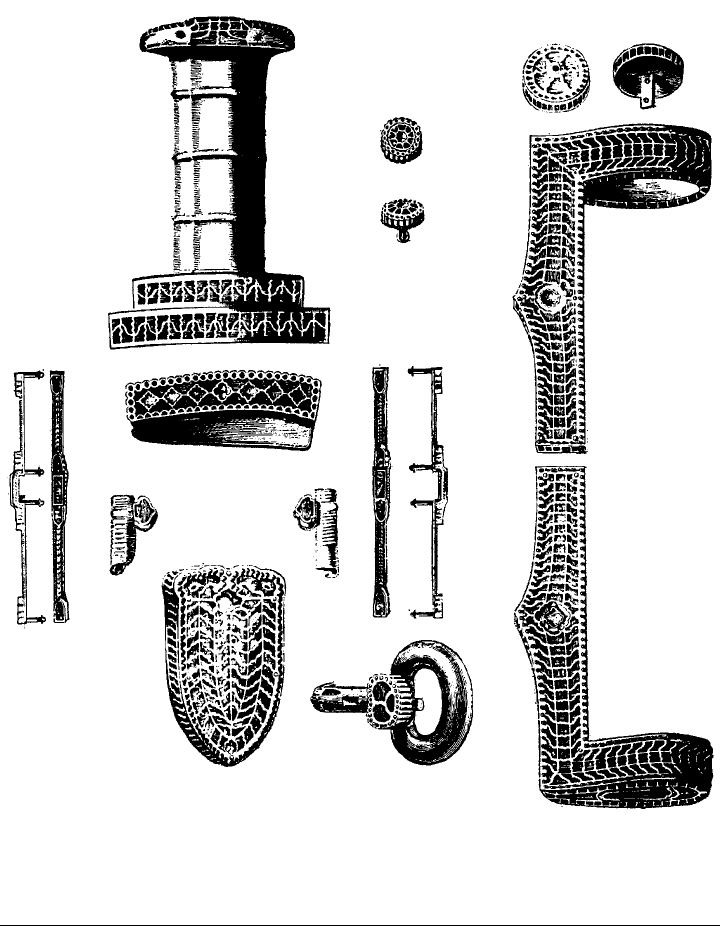

Fig. 2. Childeric’s “treasure” from original 1655 plates: fibula, signet ring, cloisonée ornament.

FROM VALLET AND KAZANSKI 1995. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

two thieves broke into the Bibliothèque Royal and

stole the trove. By the time they were caught, most

of the gold objects had been melted down, but a

few artifacts, such as the gold cloisonné ornament

of the sword, had been thrown into the Seine in

leather sacks, and these were recovered.

What do we know of Childeric? The sixth-

century ecclesiastic and historian Gregory of Tours

tells us something of his life in Historia Francorum

(The history of the Franks). Childeric may have

TOMB OF CHILDERIC

ANCIENT EUROPE

521

been the son of Merovech, and he was considered

a king so debauched that his own subjects drove

him into exile for eight years among the Thurin-

gians, at the court of King Basinus and Queen Ba-

sina. During this time the Roman general Aegidius

ruled the Franks in his place. Upon his departure

from court, Queen Basina followed him. They even-

tually married, and she gave birth to a son, Clovis.

Meanwhile Childeric fought a battle at Orléans

against the Visigoths and another at Angers against

the Goths and Saxons. When he died in about

A.D.

481, his son Clovis replaced him. On the basis of

this information and the way in which Gregory re-

counts Clovis’s subsequent (

A.D. 486) defeat of Sya-

grius, Aegidius’s son and heir, Childeric often has

been presented in history books as a minor Frankish

warlord whose power was based on the rather minor

and out-of-the-way northern town of Tournai.

(This is assumed because of the place of his burial.)

He is thought to have played a supporting role to

the Roman commanders in northern Gaul, who

were attempting to defend what was left of Roman

power there from the

A.D. 450s to the 480s.

Much can be learned from Childeric’s grave.

Michel Kazanski and Patrick Périn offer a recon-

struction of the burial and comment on how it fits

into the complex and changing world of the later

fifth century. The polychrome gold-and-garnet or-

nament so prominent in the grave closely parallels

the finds at another contemporary princely warrior

grave at Pouan, in Northeast France. The style

points particularly to the Danube region, where rich

assemblages like those in Pannonia at Apahida (now

in Hungary) and Blucina (now in the Czech Repub-

lic) define an international barbarian elite style asso-

ciated with the Hunnic empire. This “barbarian”

side of the Childeric assemblage also is reflected in

such details as the gold bracelet, which Joachim

Werner has shown was the symbol of German royal-

ty, set permanently on the wrist when the king first

mounted the throne. In the tradition of late imperi-

al “chieftains’ graves,” Childeric had a panoply of

weapons. No evidence has survived of an angon, a

kind of harpoon, or a shield, which are typical com-

plements to such an assemblage, but their vestiges

could have looked like so much rusty iron to on-

lookers in 1653.

There was a spear (the figure on the signet ring

is shown grasping one, as a symbol of royal authori-

ty) and a throwing axe (francisca)—everyday weap-

ons, balancing the parade-ground pomp of the

gold-and-garnet double-edged long sword and the

short, single-edged scramasax. The style of the very

fine cloisonné ornament on these weapons recalls

Byzantine-Sassanid techniques crafted in Byzantine

workshops and often distributed as diplomatic gifts.

Could Childeric have traveled east and received

them, perhaps during his long Thuringian exile? Ka-

zanski sees the Childeric material as reflecting mo-

tifs and techniques widespread in the Mediterra-

nean world; he and Périn suggest that at least some

of the work may have been done locally for

Childeric, perhaps by craftspeople trained in the

East. There is thus an international flavor to the bar-

barian side of the burial.

The Roman side is represented most strongly by

a gold cruciform fibula with a finely decorated foot.

Such brooches were worn by high-ranking Roman

officials, affixing to the right shoulder the official

purple cloak, or paludamentum. The gold signet

ring, too, suggests both the authority of a Roman

commander and the technology of writing: it is used

to seal orders. The image engraved upon it deftly

blends the two sides, Roman and barbarian: the

king is depicted as a Roman general with cloak and

body armor, but he has long hair. Long hair, a sym-

bol of vitality, was the prerogative of the royal lin-

eage with its claim to divine ancestry.

There were said to have been two human skulls

in the grave, one smaller than the other, and this led

to suggestions that Childeric had been buried with

his wife, Basina. A sphere of rock crystal, always a

feminine artifact, was found in the assemblage, but

there are no other clearly feminine objects, so this

theory seems unlikely. More plausible is the hypoth-

esis that a horse was buried within or near the king’s

grave (a horse’s skull was found). This is a custom

with many parallels in the Germanic world, and

some of the iron fragments could have derived from

harness equipment. Indeed some think the enig-

matic decorative objects, the bull’s head and the

golden bees—finds that remain unique—could have

ornamented the royal harness rather than a royal

robe, as was long thought.

In the 1980s understanding of Childeric’s grave

and its significance was revolutionized by a series of

excavations led by Raymond Brulet. This research

was part of a larger investigation of Tournai, origi-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

522

ANCIENT EUROPE

nally a Roman town of secondary importance locat-

ed at the border of two civitates, or states, whose

status rose in the late empire until it became the seat

of a bishopric. Why was a Frankish war leader like

Childeric buried there? Nothing in the meager writ-

ten sources suggests any specific connection, let

alone a reason. What was the context of the grave?

Was it isolated, as has often been suggested?

The site of the grave itself is precisely known,

thanks to Chifflet, but inaccessible: a house with a

deep cellar has replaced it. Brulet was able to exca-

vate underneath the street in front of it, and he ob-

tained permission from the homeowners to dig

trenches in their backyards. It soon became clear

that Childeric’s grave was part of a cemetery where

the northern Gallo-Frankish style of furnished buri-

al was practiced: weapons common in men’s graves

and jewelry in women’s graves, with a funerary de-

posit of late imperial tradition common to both. It

is possible, even plausible, that Childeric’s was the

“founder’s grave,” the focal point around which the

cemetery grew. The two most unexpected discover-

ies were the monumental conception of the entire

tomb and evidence of lavish sacrifice no doubt asso-

ciated with the funeral. The archaeological features

upon which these deductions rest are three pits with

several horse burials surrounding the royal grave

like satellites and an undisturbed zone encompass-

ing the royal grave itself. This is interpreted as evi-

dence of a monumental tumulus, or grave mound,

20 meters or more in diameter.

Twenty-one horses were packed into the three

pits. All of the skeletal material was studied careful-

ly, and carbon-14 tests were run on bones from five

animals. The results focus on the later fifth century

as the most likely time of burial. The animals them-

selves were clearly a very selective, not a random,

group. Most were geldings—warhorses—and many

of the rest were stallions; only one probable mare

could be identified. Four were colts, and seventeen

were mounts, adults ranging from six to eighteen

years old. This seems to have been the royal stable,

sacrificed in a lavish gesture at Childeric’s funeral.

The king was buried in a stoutly built timber fu-

nerary chamber over which the great tumulus was

built. It would have been clearly visible from the

Roman road, passing a little to the south on its way

to the bridge over to the right bank of the Schelde

(Escaut) River, where the main part of the town was

located. The royal tumulus thus would have be-

come perhaps the most striking monumental fea-

ture of the landscape around the town. It fits well

with the lavish nature of the grave goods and with

the extravagant gesture of sacrificing the royal sta-

ble. Was the funerary symbolism meant to recall the

mighty figure of Attila, the great war leader in the

time of Childeric’s youth, who also was buried

under a great tumulus and whose funeral featured

mounted Huns circling it, singing laments?

Guy Halsall, who has insisted on the need to

understand the ceremonial and even theatrical as-

pects of funerary practice, calls the scale of

Childeric’s burial display staggering. He also asserts

that it was not Childeric but rather his son, Clovis,

who created the tomb to demonstrate his right to

succession. There is no evidence to support this hy-

pothesis; indeed if Childeric already controlled Gaul

as far south as the Loire, as Halsall, following the re-

visionist thesis of Edward James, argues, the choice

of a small town far to the north to make this demon-

stration seems curious.

Brulet suggests that Tournai may have been

where Childeric’s ancestors were buried; a contem-

porary Roman writer, Bishop Apollinaris Sidonius,

relates that about

A.D. 450 the Salian Franks under

Clodio seized the nearby civitas of Arras. This is

likely to have been Childeric’s grandfather, who

then occupied the lands as far south as the Somme.

As Périn points out, funerary archaeology supports

this limit for Frankish power in Childeric’s day, and

Tournai makes more sense as a central place within

it. Childeric’s burial always has seemed exceptional

for the lavish display of grave goods; Brulet’s recon-

struction of the funerary environment makes it

stand out all the more, accentuating the pagan and

barbarian resonance of this cosmopolitan funerary

monument.

As imperial authority was fragmenting through-

out the western empire and new polities, mostly

identified with barbarian leaders and peoples, were

emerging to replace it, funerary ritual offered a po-

tent means to claim power symbolically. There is no

reason to assume that so successful and decisive a

figure as Childeric in the complex and changing po-

litical and cultural environment of the day would

not have decided so fundamental a matter as his

own funeral. Indeed he appears to have fashioned

from various traditions (most notably the Germanic

TOMB OF CHILDERIC

ANCIENT EUROPE

523

“chieftain’s burials” that his Frankish ancestors had

known for generations) a bold new funerary model

fit for a king. Within a few years the astounding suc-

cess of Clovis, eliminating rival rulers and conquer-

ing most of Roman Gaul, changed all the funda-

mentals of the situation. Clovis centered his new

power on Paris, in the Seine basin, far southwest of

Tournai. Furthermore, by converting to Catholic

Christianity, Clovis turned away from the too pagan

funerary model of his father. His own death in Paris

in

A.D. 511 opens a new funerary chapter, that of

royal ad sanctos burial (burial next to or near a mar-

tyr or a saint-confessor).

See also Merovingian Franks (vol. 2, part 7); Sutton Hoo

(vol. 2, part 7); Merovingian France (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brulet, Raymond. “La sépulture du roi Childéric à Tournai

et le site funéraire.” In La noblesse romaine et les chefs

barbares du IIIe au VIIe siècle. Edited by Françoise Val-

let and Michel Kazanski, pp. 309–326. Association

Française d’Archéologie Mérovingienne Mémoire 9.

Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France: Musée des Antiquités

Nationales, 1995.

———, ed. Les fouilles du quartier Saint-Brice à Tournai.

Vol. 2, L’environnement funéraire de la sépulture de

Childéric. Louvain-la-Neuve, France: L’Université

Catholique de Louvain, 1990–1991. (Details the exca-

vations of the 1980s, including the original specialist re-

ports.)

Carver, Martin. Sutton Hoo: Burial Ground of Kings? Lon-

don: British Museum Press; Philadelphia: University of

Pennsylvania Press, 1998. (See chap. 5.)

Cochet, Abbé. Le tombeau de Childéric I, roi des Francs, re-

stitué à l’aide de l’archéologie. Paris: Gerald Montfort,

Brionne, 1859. (A nineteenth-century attempt to put

the Childeric grave in context.)

Dumas, Françoise. Le tombeau de Childéric. Paris: Bibliothè-

que Nationale, Département des Médailles et Antiques,

1976.

Gregory of Tours. The History of the Franks. Translated and

with an introduction by Lewis Thorpe. Harmonds-

worth, U.K.: Penguin Books, 1974. (See book 2, sec-

tions 9, 12, and 18 on Childeric and sections 27–43 on

Clovis.)

Halsall, Guy. “Childeric’s Grave, Clovis’ Succession, and the

Origins of the Merovingian Kingdom.” In Society and

Culture in Late Antique Gaul: Revisiting the Sources.

Edited by Ralph W. Mathiesen and Danuta Shanzer,

pp. 116–133. Aldershot, U.K.: Ashgate, 2001.

James, Edward. The Franks. Oxford: Blackwell, 1988. (A re-

visionist view of Childeric.)

Kazanski, Michel, and Patrick Périn. “Le mobilier de la

tombe de Childéric I: État de la question et perspec-

tives.” Revue archéologique de Picardie 3–4 (1988): 13–

38.

Müller-Wille, Michael. “Königtum und Adel im Spiegel der

Grabkunde.” In his Die Franken: Wegbereiter Europas,

2 vols. Vol. 1, pp. 206–221. Mainz, Germany: Verlag

Philipp von Zabern, 1996.

Périn, Patrick. La datation des tombes mérovingiennes: Hi-

storique, méthodes, applications. With a contribution by

René Legoux. Geneva, Switzerland: Librarie Droz,

1980.

Périn, Patrick, and Laure-Charlotte Feffer. Les Francs. Vol.

1, A la conquête de la Gaule. Paris: Armand Colin,

1997.

Werner, Joachim. “Neue Analyse des Childerichgrabes von

Tournai.” Rheiisches. Vierteljahrsblatter 35 (1971):

43ff.

B

AILEY K. YOUNG

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

524

ANCIENT EUROPE

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

EARLY MEDIEVAL IBERIA

■

Although early medieval Spain and Portugal may

seem to stretch the definition of the “barbarian

world” considerably—from the point of view of

contemporaries they were perhaps one of the most

“civilized” parts of the Western world at the time—

they provide an interesting view of the transforma-

tion of the classical tradition as it merged with other

cultures and gradually developed into new tradi-

tions that we recognize in the modern world.

It is only since the last decades of the twentieth

century that archaeology has begun to transform

our understanding of early medieval Iberia. In the

middle decades of the twentieth century, the ar-

chaeology of Spain and Portugal was for political

reasons somewhat isolated from outside trends and

restricted in its discourse. Since the 1980s, medie-

val archaeology in Spain has benefited tre-

mendously from a great expansion in archaeological

research and from active and energetic debate of

the theoretical issues. Portuguese archaeology has

developed less rapidly, but important new work

began to appear in the 1990s. Well-documented

salvage excavations in urban centers, more

detailed study of the detritus of everyday life (such

as utilitarian pottery, animal bones, and traces of ir-

rigation systems), and regional surveys of surface ev-

idence for settlements are among the new forms of

evidence available; in part it is the freedom to dis-

cuss issues of social theory such as feudalization,

structures of state power, and processes of ethnic

distinction that has driven this expansion of archae-

ological research.

HISTORICAL OVERVIEW

A brief overview of the sequence of events known

from written historical sources helps to provide a

framework for understanding the effects of modern

archaeology on our understanding of early medieval

Iberia. The Early Middle Ages have rarely been

treated as a unified topic by historians; a great divide

has traditionally existed between historians who

study sources written in Latin and those who study

sources in Arabic. The Latin sources tend to be

frustratingly sparse and brief, but they are the only

evidence for the period before 711 and the principal

evidence for northern Spain after that date as well.

The Arabic sources are more informative but also

more limited in their coverage, and less accessible to

most Western scholars. Only the florescence of ar-

chaeological research beginning in the late twenti-

eth century has made it possible to transcend this

linguistic divide and see the continuities in the Early

Middle Ages of Spain and Portugal.

In

A.D. 400, Spain and Portugal had been part

of the Roman Empire for hundreds of years. A com-

plex provincial administration based in major cities,

trade connections with the entire Mediterranean

basin, and a cosmopolitan culture combining classi-

cal Latin learning with the new imperial religion of

Christianity were all part of the legacy of Roman

rule. A few years later, however, the defenses of the

western Roman frontier collapsed, and the Suevi-

ans, Vandals, and Alans, tribes from what is now

Germany, entered the Roman provinces. The Suevi-

ans, together with fragments of the other tribes,

ANCIENT EUROPE

525

Selected sites in early medieval Iberia.

took over what is now northern Portugal and north-

western Spain.

As the Western Roman Empire collapsed dur-

ing the course of the fifth century, the Visigoths (a

Germanic tribe from eastern Europe) formed a

kingdom in southern France that eventually ex-

panded into Spain. Over the course of the fifth cen-

tury, the Visigoths extended their control over all of

Roman Spain and Portugal except for the Suevian

enclave in the northwest. Through a long series of

wars with the Suevians, the native tribes of moun-

tainous northern Spain, and eastern Roman armies

that attempted to reestablish Roman rule in south-

ern Spain, the Visigothic kings eventually united all

of the Iberian Peninsula (together with a small por-

tion of southern France) under their rule by the

early seventh century. In doing so they created a tra-

dition of central authority and ideological uniformi-

ty, all focused on their capital in Toledo, that gave

them the most powerful government in western Eu-

rope at the time.

Between 711 and 720, an invasion by a small

Arab and Berber army from North Africa overthrew

the Visigothic kingdom, and all of Spain and Portu-

gal became part of the Islamic Empire. Arab rule

seems to have been established quickly and with lit-

tle disruption of society, but a series of civil wars

among the conquerors over the next several decades

may have been more destructive. The developing

divisions within the Islamic world soon resulted in

the establishment of an independent Arab emirate

in al-Andalus, as the Arabs called their Iberian

realm, ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. By the tenth

century this evolved into an independent caliphate,

centered on the city of Córdoba.

Unlike the Visigoths, the Arabs were unable or

unwilling to maintain central control in the moun-

tains of northern Spain. Perhaps as early as 718,

some Visigothic nobles in the Asturias of northwest-

ern Spain had set up an independent, Christian

kingdom. This kingdom gradually extended its con-

trol over Galicia, León, and Castille. During the

ninth century other small Christian realms were

formed by the Franks in Catalonia and the Basques

in Navarre. By

A.D. 1000, although the Arab Ca-

liphate of Córdoba controlled most of the Iberian

Peninsula, the Kingdom of León, the Kingdom of

Pamplona, and the County of Barcelona in the

north represented the origins of what would, over

the course of the later Middle Ages, evolve into the

modern countries of Spain and Portugal.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

526

ANCIENT EUROPE

The written sources provide little detail,

though, to flesh out this narrative with a deeper un-

derstanding of how society worked and how people

lived their lives—in other words, the social and cul-

tural processes that guided the course of historical

events. Archaeological research is providing new in-

sights into subjects where the texts raise many ques-

tions but provide few clear answers, such as the defi-

nition and evolution of ethnic and religious

identities, the processes of political and social con-

trol, and the demographic and economic basis of

society.

ETHNIC AND RELIGIOUS

IDENTITIES

Ethnic and religious differences such as the distinc-

tions between Catholic Christians and Arian Chris-

tians, between Christians and Muslims, between

Romans and Goths or Suevians, between Latins and

Arabs, or between Arabs and Berbers were of para-

mount importance from the point of view of the

writers of the historical sources, and the persistence

of other unassimilated minorities such as Basques

and Jews throughout this period added to the di-

verse mixture. What is not clear is the practical im-

portance that these categories had in reality. They

evolved over time, and distinctions that were impor-

tant in one period became unimportant later on. By

showing how these identities affected behavior, ar-

chaeology makes it possible to understand their

evolution more fully.

Rome’s Spanish provinces were among the

most romanized parts of the empire, meaning that

the native populations had widely adopted Roman

culture and ethnicity. The modern Castilian (Span-

ish), Portuguese, and Catalan languages are all de-

scended from the Latin brought by the Romans,

and the Catholic religion of Spain and Portugal was

a creation of the Roman Empire. It is not clear to

what degree local ethnic identities survived roman-

ization—certainly the Basques in the Pyrenees re-

tained their language and identity, and other peo-

ples in remote parts of the peninsula may have as

well. Similarly, scattered pre-Christian religious

practices are likely to have carried on for a long time

in rural areas, long after the people who maintained

them had become nominally Christian. But for the

most part, as far as one can see in the available evi-

dence, the Iberian Peninsula in

A.D. 400 was inhab-

ited by people who were Roman in ethnicity and

Catholic Christians by religion.

The Germanic invasions of the fifth century dis-

rupted this seeming unity by introducing new rul-

ing elites that identified themselves as ethnically

Suevian or Visigothic. The Visigoths were also dis-

tinct religiously, because they adhered at first to a

different theological tradition in Christianity known

as Arianism, characterized by an interpretation of

the Trinity emphasizing the separateness of its ele-

ments rather than their unity as manifestations of a

single god. Although the distinction between Ari-

ans and Catholics was of great importance to theo-

logians, it seems to have had little practical effect on

daily life. There is no way, for example, to distin-

guish an Arian cathedral from a Catholic one from

their archaeological traces, nor do people seem to

have made an effort to use clothing, household be-

havior, or burial rituals to proclaim their identity

with one or the other form of Christianity. If there

was an effect, it was a negative one—that only after

589, when the Visigothic regime officially adopted

Catholicism, was the powerful intellectual tradition

of the Hispano-Roman Catholics turned to the ac-

tive ideological support of the Gothic state.

This conflict, however rarified, may nonetheless

have had an effect on the attitudes of the Spanish

Church. Jerrilynn Dodds, in Architecture and Ideol-

ogy in Early Medieval Spain (1990), has suggested

that the defensive position of the Spanish church,

subordinated first to the Arian Visigoths and later

to Islam, manifested itself architecturally in a use of

constricted, horseshoe-shaped arches and apses as

well as screens or barriers separating choir from con-

gregation to create secretive, enclosed spaces for the

performance of the liturgy. It is difficult, however,

to verify such interpretations of subtle, subcon-

scious meanings.

The Visigoths and Suevians constituted only a

small minority of the population. In the fifth centu-

ry their ethnic identity must have been quite distinct

from that of the native Hispano-Roman population,

but this identity has left few obvious traces archaeo-

logically. They seem to have adopted the culture of

the Roman provinces very rapidly in almost all re-

spects. What were traditionally identified as Visi-

gothic cemeteries in northern Spain, for example,

are now thought by many to be related to changes

in Roman society, not to Visigothic traditions. A

EARLY MEDIEVAL IBERIA

ANCIENT EUROPE

527

few artifact types may have served specifically to sig-

nify this ethnic distinction, such as eagle-shaped

brooches, but over time the sense of ethnic differ-

entness between Hispano-Romans and the Ger-

manic conquerors seems to have lost its importance

to people. For the most part, the archaeological evi-

dence suggests that the Visigoths and Suevians rap-

idly assimilated to Hispano-Roman culture. By the

seventh century, the ethnic distinction between

Hispano-Romans and the Germanic Visigoths or

Suevians seems to have merged with and been

superseded by concepts of social class and wealth.

Like the distinction between Arianism and Cathol-

icism, this ethnic divide does not seem to have had

enough practical importance to sustain itself in the

long run. In the eighth century and later, Latin

Christians in Spain seem to have regarded their

Visigothic and Roman pasts as parts of a single

cultural heritage.

The social divisions brought about by the Arab

conquest proved to be a different matter. Like the

Visigoths and Suevians, the Arabs and Berbers were

at first a small minority relative to the native popula-

tion, and initially they brought few significant cul-

tural differences, with the important exception of

their religion. Unlike Arianism, Islam manifested its

differentness not only in abstract theological con-

cepts but also in many aspects of daily life, from

what one could eat or drink, to the daily routine of

prayer, to the appropriate placement of the dead in

their graves. This religious distinction is not only

more visible archaeologically, but it also would have

given the boundary between Muslims and Chris-

tians more force in processes of cultural change.

Cultural assimilation worked both ways in this in-

stance—the Latin Christian population of al-

Andalus gradually assimilated to the culture of their

rulers, becoming Muslim Arabs, but the Islamic civ-

ilization that they adopted was itself heavily influ-

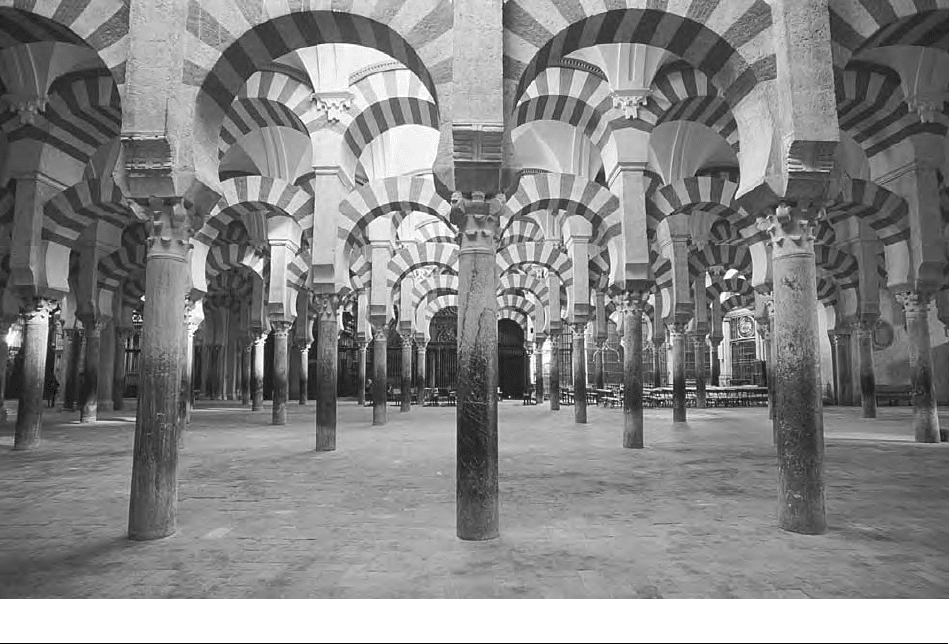

enced by Hispano-Roman culture. The Great

Mosque of Córdoba, for example, built in stages

from the eighth to tenth centuries, combines ele-

ments of Hispano-Roman and Byzantine architec-

tural styles into a building whose function was spe-

cifically Islamic (fig. 1).

The immediate effect of the Arab conquest on

the archaeological record was probably small, due

to the limited numbers of the invaders. It is debat-

ed, for example, whether Berber styles of pottery

were introduced to Spain in the eighth century.

The process of Islamization of the native pop-

ulation, however, had a more prominent impact

over time; it is likely that by

A.D. 1000 a majority

of the population had converted to Islam, and

Arabic was probably becoming the most common

language.

Food remains provide one way to observe this

process. In Roman times, pork was an important

source of meat in many parts of Spain, and this con-

tinued to some extent through the Visigothic peri-

od. After the Arab conquest, the frequency of pig

bones in archaeological sites gradually declined,

probably indicating conversion of the population to

Islam, which prohibits the eating of pork. Pig bones

usually continue to be present in small quantities,

though, suggesting the presence of a Christian mi-

nority even in mainly Muslim communities. An ex-

ception that proves the rule is a site in southeastern

Spain called the Rábita de Guardamar, a retreat

where Muslim warriors could combine asceticism,

religious contemplation, and defense of their faith.

Not surprisingly, such a specifically Islamic site lacks

pig bones.

POLITICAL COMPLEXITY AND THE

ORGANIZATION OF SOCIETY

As the rulers changed from Romans to Visigoths to

Arabs, the structures of political control and social

dominance, unsurprisingly, changed as well. The

scanty written documentation gives little insight

into the processes of control, however, except to

some degree in the caliphate toward the end of the

Early Middle Ages.

The Roman government was not the massive

bureaucratic system that modern governments are,

but by ancient standards it was a powerful and ambi-

tious state. A complex taxation system was adminis-

tered by professional civil servants, and the proceeds

were used to support a standing army, public works

such as roads and bridges, and of course the admin-

istrative system itself. The government produced

massive quantities of coinage as a medium for its

taxes and expenditures, and it produced many facili-

ties such as forts and government buildings.

As the Roman Empire disintegrated, its succes-

sors such as the Visigoths and the Suevians attempt-

ed to retain as much of the Roman administrative

system as served their purposes. Invasion and war-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

528

ANCIENT EUROPE

Fig. 1. Rows of columns inside the Mezquita mosque in Córdoba, Spain. © VITTORIANO RASTELLI/CORBIS. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

fare must have disrupted many governmental func-

tions, though, and they had probably already been

in decline in later Roman times. In the middle of the

fifth century, for example, while the city of Tarrago-

na was still under Roman administration (which

lasted there until around 470), what had earlier

been public buildings and spaces, such as the pro-

vincial forum, had clearly lost their political function

and were used as quarries for old building stone and

dumping grounds for garbage. In Valencia, the

Roman forum was replaced in the fifth century by

a church (probably the city’s cathedral) and a ceme-

tery, not only indicating the decline of the former

civic administration but also symbolizing how the

church hierarchy was replacing the old institutions

of local authority.

The Suevians and Visigoths, who had no tradi-

tion of administrative government, relied on surviv-

ing Roman institutions to control and exploit their

new territories, but probably at a more limited level

of activity. They produced coinage derived from

Roman types, but in limited quantities and mostly

in gold, suitable for large payments within the rul-

ing class but not for everyday use in small transac-

tions. Some public works and state construction

projects continued under the Visigoths, but the evi-

dence is much more scarce than for the Roman peri-

od; no facilities for a professional standing army are

apparent, for example. The state seems also to have

been less able to enforce even the policies it was in-

terested in; for example, despite draconian legisla-

tion in the seventh century intended to suppress Ju-

daism, Jewish tombstones inscribed in Hebrew

were still made.

This decline of state control seems to have af-

fected the entire population in another way. The

Roman government had been able to maintain

peace and enforce laws well enough for people to

live dispersed throughout the country with reason-

able security. As Roman rule broke down, however,

people tended to live in more clustered settlements,

often in defensible locations, in some cases reusing

prehistoric hillforts. This change suggests that the

people in the countryside were at increased risk

from marauders, bandits, feuds, or other forms of

small-scale violence.

EARLY MEDIEVAL IBERIA

ANCIENT EUROPE

529

In sociopolitical organization as in many other

things, the Christian north and the Islamic center

and south followed different trajectories after the Is-

lamic conquest. This has been made most clear since

the late 1970s through studies of the social role of

castles.

In much of western Europe, particularly France,

medieval castles first appeared as part of a social

transformation in which a class of feudal lords

emerged during the tenth and eleventh centuries

and seized for themselves on a local basis the politi-

cal powers formerly exercised by the kings as well as

by communities of free peasants, who were then re-

duced to serfdom. Castles served as the focal points

of feudal settlement, and thousands were built dur-

ing the decades around the year 1000. As feudal

lords obtained economic power over the peasants,

previously dispersed rural settlement was restruc-

tured in the form of larger villages located near the

castles, so that compulsory labor service was easily

accessible to the lords.

This transition to feudalism is generally agreed

to have occurred also in Catalonia, which had close

ties to France at the time. It is more disputed to

what degree these changes happened in other parts

of Spain or in Portugal. In the Kingdom of León,

castles were built and villages were established as in

France, but they seem to have happened separately,

not as part of a single, drastic transformation of soci-

ety. The written sources likewise suggest that nei-

ther royal power nor the freedom of the peasantry

was so completely usurped there.

In Islamic al-Andalus, as well, castles became

abundant, in contrast to their absence in most other

Islamic lands at the time. And in some ways these

castles may have had functions similar to those of

northern Spain, especially in areas where the Mus-

lim elite was formed from converted Hispano-

Gothic nobles. Because society was organized dif-

ferently in al-Andalus, though, the seizure of power

by local nobles that was the essence of feudalism

did not happen there. Castles in al-Andalus served

as defensive refuges and as local outposts of the

central administration, so rather than causing a

restructuring of rural settlement for the benefit

of local lords, they were instead placed where people

already were.

POPULATION, TRADE, AND

THE ECONOMY

Traditionally, the end of the Roman Empire was

imagined in apocalyptic terms of collapse and de-

struction. Modern research has modified this atti-

tude in many important ways, emphasizing the con-

tinuities from Roman times to the Early Middle

Ages as well as the creativity and vitality of late an-

cient and early medieval civilization. Nevertheless,

many changes occurred in the material aspects of

life. Although there are difficulties with the evi-

dence, the overall pattern appears to be one of eco-

nomic decline from the later part of the Roman pe-

riod through the Visigothic period, with gradual

recovery beginning in the ninth or tenth century.

These trends appear in the evidence relating to rural

population, urbanism, and trade.

Under Roman rule, the Iberian Peninsula was

densely settled with an assortment of towns and vil-

lages, small farms, and large aristocratic villas, most

often situated in the best agricultural land. Al-

though many of these sites remained occupied into

the fifth and sixth centuries, the number of sites de-

clined, and those that remained were smaller; also,

as noted above, new sites were often in defensive lo-

cations. By the seventh century, a very different pat-

tern had taken shape: people lived mostly in small

sites, which were much less abundant and which

were commonly located in mountainous areas or in-

accessible hilltops. This pattern, which suggests

both a substantial decline in population and a con-

cern with defense instead of maximization of pro-

duction, continued through the Arab conquest into

the ninth century. Only from the late ninth or tenth

century does there seem in many regions to have

been an expansion of settlement back into lower,

more productive, but also more vulnerable areas.

Towns and cities followed a broadly parallel

trend. By late Roman times, not only the public

buildings but also many residential areas of the

towns had fallen out of use, suggesting a diminished

number of residents. Although written sources

seem to indicate that towns and cities remained im-

portant centers of civil and religious administration

throughout the Early Middle Ages, the archaeologi-

cal evidence is sparse. In many urban excavations in

Spain, a late Roman level is immediately followed by

deposits of the tenth or eleventh century or later,

suggesting relatively little occupation during the in-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

530

ANCIENT EUROPE