Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Stow settlement included about seven individual

farms.

Artifactual evidence indicates that the West

Stow village was inhabited from the early fifth cen-

tury to the mid-seventh century. Pottery and metal-

work suggest that the village was first occupied in

about

A.D. 420. The presence of Ipswich ware, dis-

tinctive kiln-fired pottery that was produced on a

slow wheel, indicates that the village must have

been inhabited until about

A.D. 650. Detailed chro-

nological analyses indicate that no more than three

or four farmsteads were occupied at any one time,

so West Stow was probably more of a hamlet than

a true village.

One of the main goals of the West Stow excava-

tion was to study Early Anglo-Saxon farming and

animal husbandry practices. The technique of flota-

tion was developed in the 1960s to recover small

seeds and other plant materials from archaeological

soils. West Stow was one of the first sites in Britain

where flotation techniques were used. Remains of

wheat, rye, barley, and oats were recovered from

several of the Anglo-Saxon features at West Stow.

Some of the fifth-century features produced the re-

mains of spelt wheat (Triticum spelta), a form of

wheat that was grown commonly in Roman Britain.

The presence of this variety of wheat may indicate

some degree of continuity between Roman and

Early Anglo-Saxon farming practices. By the sev-

enth century, however, spelt wheat seems to have

disappeared from Anglo-Saxon agriculture. It was

replaced by other varieties of wheat and rye.

The West Stow site produced more than

180,000 animal bone fragments that could be used

to study Anglo-Saxon animal husbandry and hunt-

ing practices. These faunal remains have shown that

the denizens of West Stow kept herds of cattle,

sheep, and pigs. The cattle probably were grazed on

the rich pastures along the Lark River edge, while

the sheep would have been herded on the drier up-

land areas behind the site. Pigs were most numerous

in the early fifth century; most likely they were herd-

ed in the wooded areas along the river terraces.

Herding was supplemented by the occasional hunt-

ing of red deer, roe deer, and waterfowl; poultry

keeping; and fishing for pike and perch in the Lark

River. The early Anglo-Saxons also kept a small

number of horses. These animals, which were the

size of large ponies, may have been used for riding

and traction, but they also were eaten on occasion.

The large, straight-limbed Anglo-Saxon dogs were

about the size of modern German shepherds. They

may have been used as hunting, herding, and guard

dogs.

One of the most difficult questions for archaeol-

ogists to answer is exactly who lived at the West

Stow village. Based on traditional historical evi-

dence, the early Anglo-Saxons were seen as mi-

grants from continental Europe who entered Brit-

ain shortly after the withdrawal of Roman military

power in about

A.D. 410. Later scholarship has sug-

gested that the Anglo-Saxons may have been a small

military elite that took control of eastern England

in the fifth century. In that case, the denizens of

West Stow may have been native Britons who

adopted Anglo-Saxon material culture, including

pottery, metalwork, and building styles, from their

Continental overlords. While it may never be

known with certainty who lived in West Stow vil-

lage, the archaeological evidence for spelt cultiva-

tion points to significant economic continuity be-

tween the Romans and the early Anglo-Saxons.

A program of experimental reconstruction of

the West Stow farm buildings was begun in 1974.

Several SFBs and a single hall have been reassem-

bled using early medieval tools and techniques.

These buildings currently are part of a county park

that is open to the public.

See also Ipswich (vol. 2, part 7); Animal Husbandry (vol.

2, part 7); Agriculture (vol. 2, part 7); Anglo-Saxon

England (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Crabtree, Pam J. West Stow: Early Anglo-Saxon Animal Hus-

bandry. East Anglian Archaeology 47. Ipswich, U.K.:

Suffolk County Department of Planning, 1989.

West, Stanley. West Stow: The Anglo-Saxon Village. East An-

glian Archaeology 24. Ipswich, U.K.: Suffolk County

Department of Planning, 1985.

P

AM J. CRABTREE

■

WINCHESTER

Winchester, Roman Venta Belgarum, the principal

royal city of Anglo-Saxon England, is today the ad-

WINCHESTER

ANCIENT EUROPE

501

ministrative center for the county of Hampshire in

southern England. To a great extent, the archaeolo-

gy of Winchester was still terra incognita in 1961

when the first large-scale excavation took place.

Nothing certain was known of its origins and almost

nothing of the plan or development of the Roman

town. As for Winchester after the Romans, it did

not exist as an organized field of archaeological en-

quiry. The contrast between the written evidence

for the importance of early medieval Winchester and

the virtual absence of an archaeology of that period

compelled attention. The aim of the work that the

Winchester Excavations Committee began in 1961

was, according to “The Study of Winchester”

(1990),

to undertake excavations, both in advance of build-

ing projects, and on sites not so threatened, aimed

at studying the development of Winchester as a

town from its earliest origins to the establishment

of the modern city. The centre of interest is the city

itself, not any one period of its past, nor any one

part of its remains. But we can hope that this ap-

proach will in particular throw light upon the end

of the Roman city and on the establishment and

development of the Saxon town, problems as vital

to our understanding of urban development in this

country, as they are difficult to solve. Further it is

essential to this approach that the study and inter-

pretation of the documentary evidence should go

hand in hand with archaeological research.

It was also realized from the start, as stated in the

same publication, that this would have to be “a

broadly based exploration of the fabric of the city,

across the full range of variation in wealth, class, and

occupation. This involved more than gross distinc-

tions between castle, palace, and monastery on

the one hand and the ‘ordinary’ inhabited areas

of the city on the other.” This was the founding

manifesto of urban archaeology, copied in both

concept and execution in a multitude of towns and

countries.

Eleven years of excavation followed, for ten or

more weeks each summer, aided by two-hundred

student volunteers from over twenty-five countries

working on four major sites and many smaller ones

across the city and suburbs. In 1968 the Winchester

Research Unit was set up to prepare the results for

publication in a series entitled Winchester Studies. In

1972, following the end of the major campaign of

excavations, the post of City Rescue Archaeologist

was set up to make observations of sites threatened

by development and to carry out excavations as

needed. That work continues today on a permanent

basis as part of the Winchester City Museums

Service.

EARLIER PREHISTORIC CONTEXT

AND THE IRON AGE

Situated where the River Itchen cuts through the

chalk downs on its way to Southampton Water and

the sea, the city is a natural focus of long-distance

communication from east to west and north to

south. The area may have been settled in the Late

Neolithic period or perhaps earlier. From the third

century

B.C., during the Iron Age, people occupied

St. Catharine’s Hill, on the east bank of the Itchen,

south of the later city. The summit of the hill was

later encircled by a line of bank and ditch dominat-

ing the river valley below, but these defenses were

destroyed about the middle of the first century

B.C.

At that point, the focus of settlement shifted up-

stream and to the other side of the river, which be-

came the site of the future city. There, a roughly

rectangular area of about 20 hectares was enclosed

by a ditch and bank with entrances on all four sides

through which the major lines of communication

had to pass. Now known as the Oram’s Arbour en-

closure, this was a regionally and strategically im-

portant site, as fragments of Mediterranean wine

jars (amphorae) show. Occupied for some fifty

years, the enclosure was long abandoned when the

Romans passed through in

A.D. 43.

VENTA BELGARUM

There is no continuity between the Iron Age settle-

ment and the beginning of the Roman city, except

that Roman long-distance roads passed through the

northern and western entrances of the deserted

Oram’s Arbour enclosure. Timber buildings in the

upper part of the town that date to the 50s of the

first century

A.D. are the earliest traces of Roman oc-

cupation. In the valley floor, a rectangular area of

unknown size was defined by a substantial ditch.

First identified as part of a small Roman fort, it may

have been part of a religious enclosure, as the pres-

ence of a later Roman temple and a wooden statue

of the goddess Epona suggest.

In the 70s of the first century

A.D., a chess-

board pattern of graveled streets at intervals of 400

Roman feet was laid out within earth and timber de-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

502

ANCIENT EUROPE

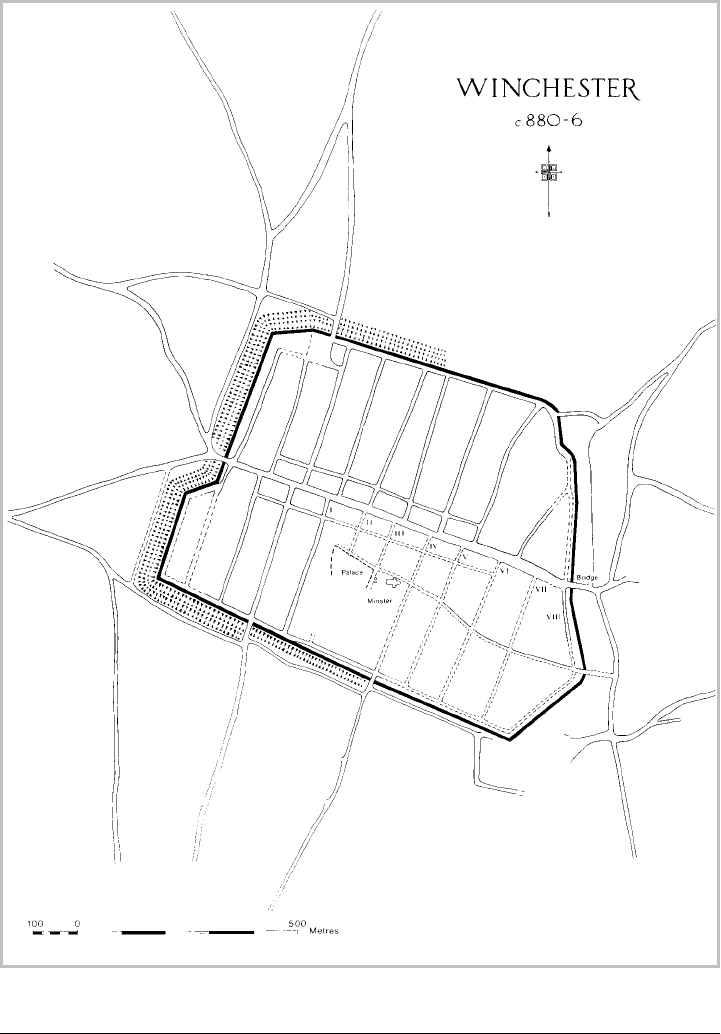

Fig. 1. Plan of the Anglo-Saxon town of Winchester, England, c. A.D. 880–886. COURTESY OF MARTIN

BIDDLE. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

fenses. A forum, the settlement’s administrative and

commercial heart, was later built on a grand scale,

filling the central block or insula, of the grid. Its

construction illustrated that the town was now the

capital of the civitas of the Belgae, as the name

Venta Belgarum (venta, or market, of the Belgae)

implies. Timber houses with tiled roofs, painted

plaster walls, and mosaic floors were built along the

streets. In the 150s and 160s, some of these houses

were rebuilt in stone, or on stone foundations, often

on a substantial scale. By the end of the second

century, water in iron-jointed wooden pipes was

fed to parts of the town, implying the existence

of an aqueduct, traces of which have been

found running along the contours to the north of

the city.

WINCHESTER

ANCIENT EUROPE

503

By A.D. 200, when the circuit of the defenses

was completed, Venta Belgarum, with an area of

58.2 hectares, was the fifth largest city of Roman

Britain. In the early third century, the defenses were

rebuilt in stone. The streets were kept clean and reg-

ularly resurfaced, and houses were still being built

and repaired into the first half of the fourth century.

Shortly after 350, however, the city underwent a

profound change. Major public buildings and the

larger townhouses were partly or wholly demol-

ished, and large areas inside the walls were apparent-

ly enclosed to form compounds possibly for cattle

and sheep awaiting slaughter for hides or shearing

for wool. The water supply was reorganized with

new iron-jointed wooden pipes, and all parts of the

walled area seem to have been more densely popu-

lated than before. Varied and intensive industrial ac-

tivity took place, and the streets continued to be re-

surfaced. The city walls were strengthened by the

addition of external bastions. The cemeteries out-

side the walls grew greatly in extent: of some 1,300

burials from the Roman era that had been excavated

through 1986, more than 1,000 were from the

fourth century. In the second half of the fourth cen-

tury, Venta seems to have become a busier, cruder,

more pressured place. A possible explanation is that

the city was no longer a civil settlement but a de-

fended administrative base and supply center, deal-

ing with the tax in kind known as the annona mili-

taris and engaged in the industrialized production

of textiles in a gynaeceum, a large-scale textile mill

under imperial control.

POST-ROMAN VENTA

The Roman town collapsed in the fifth century. The

decline is sharply reflected in the petering out of

graves at the limit of the Lankhills cemetery, one of

the most poignant images of the end of Roman

Britain. Some rough street surfaces were put down

during this period and the water supply relaid, but

the wooden pipes used for the water supply no

longer had iron collars. From this time onward,

buildings began to be abandoned and some streets

ceased to be used as thoroughfares and were instead

taken over for domestic or other use. In the mid-

later fifth century the south gate collapsed onto the

street, but traffic continued across the uncleared

rubble, and two further street surfaces were laid

above it. At some date around 600, entry was

blocked by cutting a ditch across the street, later re-

inforced by a rough stone wall. The north gate was

probably blocked at the same time, so that in the

end only one of the five east-west streets and one of

the north-south streets of the Roman grid remained

in use. The blocking of the gates shows that two

centuries after the collapse of the Roman city there

was still some authority controlling access to the

walled area.

There is evidence from widely spread parts of

the city for continuous activity of various sorts

through the fifth and sixth centuries. Traces have

been found wherever excavation has reached the

relevant deposits over areas large enough to allow

one to understand what survived and where the se-

quence was specific enough to provide some idea of

the use of the area in spite of the destruction caused

by the digging of cellars, wells, and cesspits during

the medieval and later periods. The first signs of a

barbarian Germanic presence can be dated to the

early fifth century, when the Roman city was still at

least partly functioning. Small amounts of Early

(that is, pagan) Anglo-Saxon pottery have been

found on widely distributed sites within the walls,

suggesting that there may have been as many as six

areas of Germanic occupation at that time. In addi-

tion, two later occupations have been indicated by

place-name evidence.

Outside the walls, within a seven-kilometer ra-

dius of the city, there are seven recorded sixth- to

seventh-century Anglo-Saxon cemeteries or isolated

burials. Five of these date in whole or in greater part

to the pre-Christian period. They form a cluster of

a kind unique in Hampshire and rarely paralleled in

central-southern England. This demonstrates the

relative importance of the former Venta as a focal

point in the pre-Christian Anglo-Saxon settlement

of Hampshire. Since the early 1970s, discussion has

focused on how the town’s importance can be ex-

plained and what its significance may have been for

the foundation of a minster church within the walls

in the middle of the seventh century. Some argue

that the church was founded only because the West

Saxon clergy wished to establish the church within

a former Roman town. Others maintain that it was

founded to serve an existing center of Anglo-Saxon

power and authority within the walled area. The

“authority hypothesis” provides an explanation of

the archaeological evidence as currently known.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

504

ANCIENT EUROPE

WINTANCEASTER

The arrival of Christianity c. 650 is marked by the

building of the church later known as Old Minster

in the middle of the town’s walled area. Its cross-

shaped plan, set out on a modular geometry using

the long Roman foot, appears to be derived from

northern Italy. This suggests that it was built under

the influence of St. Birinus (d. c. 650), the apostle

of Wessex, who had been consecrated in Genoa

about 630 by Bishop Asterius of Milan. The church

was founded by the Anglo-Saxon King Cenwealh of

Wessex (r. 643–672), who appears to have endowed

it with a large territory around the city. The see of

Wessex was moved to Winchester c. 660 and has re-

mained there ever since. Excavation has revealed the

long and complicated structural history of the

church, but until shortly after 900 it stood almost

unchanged. During the greater part of this period,

Winchester was not an urban place but a royal and

ecclesiastical center. It included a royal enclosure,

the cathedral church and its community, a series of

high-status private estates, and some service activity,

including ironworking, along the east-west axis,

now High Street. Only this street and one north-

south street survived in use from the Roman period,

with a post-Roman street wandering at an angle

across the grain of the Roman plan from the south-

east corner of the walled area towards the minster

and palace in the center.

In 860 Winchester was attacked by the Vikings.

There is no record that the church suffered, perhaps

because Bishop Swithun (who held his post 852–

863) had already put the defenses in order, building

a bridge across the Itchen outside the east gate in

859. The bridge may have been part of a larger cam-

paign of defense undertaken by King Æthelbald of

Wessex (r. 855–860) that saw the walls and gates

repaired.

FELIX URBS WINTHONIA

Modern Winchester has a regular pattern of streets,

comprising four elements: High Street running

from west to east; backstreets flanking High Street;

a series of north-south streets running off to either

side of High Street; and a street (now much inter-

rupted) running inside the city walls. When the

main outlines of the Roman street plan were worked

out in the early 1960s, it became clear that Winches-

ter’s present streets were not, as had long been

thought, of Roman origin: Roman buildings lie be-

neath today’s streets and Roman streets beneath

standing buildings.

Archaeologists then sought to establish when

the present street plan was laid out. Coins found in

1963 above and below the second of a series of sur-

faces of what is now called Trafalgar Street, one of

the north-south streets, showed that it was laid in

the early tenth century. Excavation below the earth-

works of William the Conqueror’s castle, built in

1067, showed that another of the north-south

streets and part of the street running inside the wall

had been resurfaced eight or nine times before

being buried below the castle, and that the first sur-

faces dated to the early tenth century or before.

Written evidence showed that some of the present

streets were already there by the tenth century. The

precinct of New Minster, founded in 901, is defined

in terms of the streets on all four sides of its site. The

street plan of Winchester is therefore Anglo-Saxon,

laid down either by King Alfred (r. 871–899) in the

880s, or (as seems increasingly likely) in the reigns

of one or other of his older brothers, possibly

Æthelbald.

There can be no doubt that the streets were part

of a single deliberate operation. The first surface is

everywhere of the same kind, of small, deliberately

broken flint cobbles, while a “four-pole” (roughly

1.2 × 5 meters [4 × 16.5 feet]) module of 20.1 me-

ters (66 feet), or one “chain,” seems to have con-

trolled the spacing of the north-south streets. Plans

of the Winchester type can be seen in a series of

other fortified places that were in use by the early

tenth century in southern England, some of them

on new sites where the street design could not have

been influenced by an existing street system of

Roman date. Earlier models need not be sought.

There is nothing in the regularity of street plans of

the Winchester type that was not well known to the

hundreds of nameless individuals who in the eighth

and ninth centuries had covered England with the

vast pattern of rectangular strip fields that were to

survive for a thousand years. This is the first great

moment of English town planning and one of the

earliest schemes of its kind in the post-Roman West.

The streets provided the skeleton upon which

a populous and vibrant city emerged during the last

century and a half of the Anglo-Saxon state. In

about 900, Alfred’s wife, Ealhswith (d. 902), estab-

WINCHESTER

ANCIENT EUROPE

505

lished a nunnery, the Nunnaminster, on her proper-

ty inside the east gate. In 901 her son King Edward

the Elder (r. 899–924) founded the New Minster

(so-called from the start to distinguish it from the

ancient cathedral, henceforth Old Minster) imme-

diately next to Old Minster in the center of the city.

In 963 Bishop Æthelwold (who served 963–984)

reformed the religious houses of the city, replacing

clerks with Benedictine monks. In 971 he relocated

his predecessor Swithun from his original grave to

a specially made gold-and-jeweled shrine and began

the reconstruction of Old Minster on a huge scale.

With the dedication of the works of Æthelwold and

his successor Ælfheah (served 984–1006) in 980

and 992–994, Old Minster become the greatest

church of Anglo-Saxon England. It is also the only

Anglo-Saxon cathedral that has been almost com-

pletely excavated, its long structural sequence eluci-

dated, and its architectural design restored on

paper. It is one of the great and most individual

monuments of early medieval Europe.

By the year 1000 the whole southeastern part

of the walled area was a royal and ecclesiastical quar-

ter, containing the cathedral and two other min-

sters, all of royal foundation, the bishop’s palace at

Wolvesey (where the bishop still resides), and a

royal palace to the west of the minsters where the

king’s treasure was kept for the first time in a perma-

nent location. Winchester was now the principal

royal city, the Westminster, of Anglo-Saxon En-

gland. It served as a center of learning, music, litur-

gy, book production and manuscript illumination,

metalwork and sculpture, and of writing in Old En-

glish and Anglo-Latin. Outside the southeast quar-

ter, the frontages of the streets were becoming fully

built up with more than one thousand properties,

many parish churches, and a wide range of craft pro-

duction and industries, not least bullion exchange

and minting. This was the golden age of the Old

English state, and Winchester was its early capital.

The city was soon to attract the attention of

outsiders. In 1006 the people of Winchester, safe

behind their walls, watched the Danish Viking army

pass on their way to the sea. In 1013 Svein Fork-

beard, king of Denmark (r. c. 987–1014) took the

city. In the years that followed, his son Cnut, king

of England and Denmark (r. 1016–1035), made

Winchester the principal center of his Anglo-Danish

North Sea empire. He and his family were buried in

Old Minster. In November 1066, the principal citi-

zens surrendered the city without a fight to William

the Conqueror, heralding a century during which

Winchester would remain second only to the bur-

geoning wealth of London.

See also Anglo-Saxon England (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Biddle, Martin. “The Study of Winchester: Archaeology and

History in a British Town, 1961–1983.” In British

Academy Papers on Anglo-Saxon England. Edited by

E. G. Stanley, pp. 299–341. Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1990. (Reviews the excavations of 1961 through

1971. Also includes a bibliography of sources published

through 1988.)

———. “Excavations at Winchester, 1971: Tenth and Final

Interim Report.” The Antiquaries Journal 55 (1975):

96–126 and 295–337.

———. “Excavations at Winchester, 1970: Ninth Interim

Report.” The Antiquaries Journal 52 (1972): 93–131.

———. “Excavations at Winchester, 1969: Eighth Interim

Report.” The Antiquaries Journal 50 (1970): 277–326.

———. “Excavations at Winchester, 1968: Seventh Interim

Report.” The Antiquaries Journal 49 (1969): 295–329

———. “Excavations at Winchester, 1967: Sixth Interim

Report.” The Antiquaries Journal 48 (1968): 250–284.

———. “Excavations at Winchester, 1966: Fifth Interim Re-

port.” The Antiquaries Journal 47 (1967): 251–279.

———. “Excavations at Winchester, 1965: Fourth Interim

Report.” The Antiquaries Journal 46 (1966): 308–339.

———. “Excavations at Winchester, 1964: Third Interim

Report.” The Antiquaries Journal 45 (1965): 230–264.

———. “Excavations at Winchester Cathedral, 1962–63:

Second Interim Report.” The Antiquaries Journal 44

(1964): 188–219.

Biddle, Martin, et al. Object and Economy in Medieval Win-

chester. Winchester Studies, vol. 7, pt. 2. Oxford: Clar-

endon Press, 1990.

Biddle, Martin, ed. Winchester in the Early Middle Ages: An

Edition and Discussion of the Winton Domesday. Win-

chester Studies, vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1977.

Biddle, Martin, and R. N. Quirk. “Excavations near Win-

chester Cathedral, 1961.” The Archaeological Journal

119 (1962): 150–194.

Clarke, Giles, et al. Pre-Roman and Roman Winchester: The

Roman Cemetery at Lankhills. Winchester Studies, vol.

3. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1980.

Collis, John. Winchester Excavations 1949–60, Vol. 3. N.p.,

n.d.

Collis, John, and K. J. Barton. Winchester Excavations, Vol.

2, 1949–1960. Excavations in the Suburbs and the West-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

506

ANCIENT EUROPE

ern Part of the Town. Winchester, U.K.: City of Win-

chester, 1978.

Cunliffe, Barry. Winchester Excavations 1949–1960. Win-

chester, U.K.: Winchester City Council, Museums and

Libraries Committee, 1964.

Keene, Derek, and Alexander R. Rumble. Survey of Medieval

Winchester. Winchester Studies, vol. 2. Oxford: Claren-

don Press, 1985.

Kjo

⁄

lbye-Biddle, Birthe. “Old Minster, St. Swithun’s Day

1093.” In Winchester Cathedral: Nine Hundred Years,

1093–1993. Edited by John Crook, pp. 13–20. Chich-

ester, U.K.: Phillimore, 1993.

———. “Dispersal or Concentration: The Disposal of the

Winchester Dead over 2000 Years.” In Death in Towns:

Urban Responses to the Dying and the Dead, 100–1600.

Edited by Steven Bassett, pp. 210–247. Leicester, U.K.:

Leicester University Press, 1992.

Lapidge, Michael. The Cult of St Swithun. Winchester

Studies, vol. 4, pt. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2003.

Rumble, Alexander R. Property and Piety in Early Medieval

Winchester: Documents Relating to the Topography of the

Anglo-Saxon and Norman City and Its Minsters. Win-

chester Studies, vol. 4, pt. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press,

2002.

Scobie, G. D., John M. Zant, and R. Whinney. The Brooks,

Winchester: A Preliminary Report on the Excavations,

1987–88. Archaeology Report, vol. 1. Winchester,

U.K.: Winchester Museums Service, 1991.

Zant, John M. The Brooks, Winchester, 1987–88: The Roman

Structural Remains. Archaeology Report, vol. 2. Win-

chester, U.K.: Winchester Museums Service, 1993.

M

ARTIN BIDDLE

WINCHESTER

ANCIENT EUROPE

507

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

VIKING YORK

■

York was already eight hundred years old when it

was captured by the Scandinavian great army in

A.D.

866 during the Vikings’ attempted conquest of En-

gland. Thereafter known as Jorvik, the town re-

mained under Scandinavian control for most of the

next eighty-eight years, ruled either by English pup-

pets or Danish or Norwegian kings. In these years

it became one of the foremost towns in northern

Europe and the central place for a large area of Scan-

dinavian settlements in Northumbria, the northeast

of England. After the expulsion of the last Viking

king, Erik Bloodaxe, in

A.D. 954, Northumbria was

incorporated into the kingdom of England but con-

tinued to be ruled by earls based in York. The town

retained a distinctive Anglo-Scandinavian culture

and allegiance for more than a century.

The Roman Ninth legion that founded York

had placed the fortress Eboracum where the naviga-

ble river Ouse cuts through moraines that give good

routes across the broad low-lying Vale of York; the

settlement was thus well positioned for good water

and land communications. When captured by the

Vikings, York was still very much a Roman place.

The stone-built defenses, main gateways, and street

layout of Eboracum and the nearby civil town

Colonia Eboracensis, largely survived into the Vi-

king era. Within the fortress an ecclesiastical enclave

had grown up around the church of St. Peter,

founded

A.D. 627 and since A.D. 735 seat of the

archbishop of York, probably with an establishment

nearby for the kings of Northumbria. With other

churches, domestic occupation, and riverside trad-

ing activity, York already had the aspects of a town,

one of very few in England at the time. The Scandi-

navians, with huge input of effort and materials,

transformed this over the next two generations to

provide political, military, administrative, religious,

industrial, and commercial and trading functions for

what was in effect a separate Viking kingdom de-

pendent on Jorvik.

To provide for Jorvik’s defense the Roman for-

tifications were put in order, in some places being

heightened with palisaded ramparts over the

Roman walls and in others being extended to incor-

porate and defend a larger area. The town within

the defenses was radically replanned to accommo-

date dwellings for a growing population and for

commercial and industrial expansion. The Roman

bridge across the river Ouse was replaced by another

crossing downstream on the site of the present Ouse

Bridge. New streets with Scandinavian names ran

down to the crossing: Micklegate (“the great

street”) from one side and Ousegate (“the Ouse

street”) and its extension Pavement from the other.

Similarly Walmgate led up to a crossing of the tribu-

tary river Foss and continued into the town as

Fossgate. This concentrated commercial activity

along the riversides and on the spur of land between

the two rivers. A network of other new streets was

laid out in relation to them.

The area is low-lying and has a drainage-

impeding clay substrate. Organic debris from the

new settlement rapidly caused anoxic (oxygen defi-

cient) ground conditions to develop that preserved

archaeological remains very well, especially the nor-

mally perishable organic components. The resultant

508

ANCIENT EUROPE

Fig. 1. Coppergate, York. Excavating post-and-wattle buildings of c. A.D. 930. © YORK ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST. REPRODUCED BY

PERMISSION

.

great depths of stratification therefore contain a

uniquely detailed record of life in the commercial

heart of a Viking town, although, being under mod-

ern York, they are difficult for archaeologists to ac-

cess.

Excavations along some of the new streets dur-

ing modern redevelopment have shown that the

frontages were divided up into individual proper-

ties. Houses were set gable end to the street front

on long narrow plots running back into the block.

Four such properties were excavated at 16–22 Cop-

pergate between 1976 and 1981. The street and the

land divisions here, established by about

A.D. 900,

have maintained their positions until the present. By

A.D. 930 the plots contained post-and-wattle build-

ings for domestic occupation and industrial scale

manufacturing. These were replaced in the 960s

and 970s by semisunken two-story plank and post-

built oak structures and again in some cases in the

eleventh century by further surface-level oak-built

structures. Excavations and observations during

building developments show that similar Viking

Age buildings and layouts exist in many other parts

of central York.

People lived in the street-front buildings. Crafts

and industries were carried out there and in build-

ings and open areas behind on the long narrow

plots. Such activities at Coppergate included wood-

working; production of iron objects; production of

copper alloy, silver, and other nonferrous metal ob-

jects; craft working of amber and other jewelry, ant-

ler combs, and textiles (including spinning, weav-

ing, dying, and the making up of garments); and

leatherworking (including shoe manufacture). Die

making for coin minting—or minting itself—may

also have gone on, Jorvik having produced vast

quantities of silver coinage in the tenth and eleventh

centuries. The site also contained evidence for re-

gional and international trade. Environmental ar-

chaeology has enabled researchers to deduce living

conditions, diet, and disease, and cemetery excava-

VIKING YORK

ANCIENT EUROPE

509

tions in various parts of Anglo-Scandinavian York

have helped determine contemporary demography.

Paganism rapidly gave way to Christianity in Vi-

king York. The former Anglo-Scandinavian cathe-

dral was probably situated north of the present York

Minster, whose site was occupied by a high-status

Anglo-Scandinavian cemetery. Lesser churches

known from documentary and archaeological evi-

dence include one surviving structure, St. Mary

Bishophill Junior. Together they imply an Anglo-

Scandinavian precursor of the medieval parish sys-

tem.

Stone sculpture dating to the ninth to eleventh

centuries from the Minster and other churches

shows that wealthy patrons stimulated a flourishing

metropolitan art tradition—also seen on leather,

wood and metal objects—reflecting both Anglo-

Saxon and Viking traditions and styles. This, along

with excavated musical instruments and document-

ed literary works demonstrate cultural aspirations in

Jorvik as well as administrative and commercial suc-

cess.

The Domesday Book drawn up on the orders of

the Norman conqueror William I shows that by

1086 Jorvik had become a city of some 1,800

households and perhaps 10,000 people, vast for

northern Europe at the time. Repeated attacks or

planned attacks by Norwegian armies between

1066 and 1085 suggest continuing Scandinavian

links. Jorvik—The Viking City, an underground

display on the Coppergate excavation site, provides

a full-scale evidence-based simulation of Copper-

gate in the 970s. Other artifacts from Viking York

can be seen in the Yorkshire Museum, York.

See also Vikings (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Addyman, P. V., ed. The Archaeology of York. 20 vols. to

date. Ongoing series issued in fascicles. York: Council

for British Archaeology, 1976–.

Hall, Richard. Viking Age York. London: Batsford, 1994.

———. The Viking Dig: The Excavations at York. London:

Bodley Head, 1984.

Additional information is available at the York Archaeologi-

cal Trust’s website at http://www.yorkarchaeology.

co.uk, especially under “Secrets Beneath Your Feet”

and “Jorvik: The Viking City.”

P.

V. ADDYMAN

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

510

ANCIENT EUROPE