Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

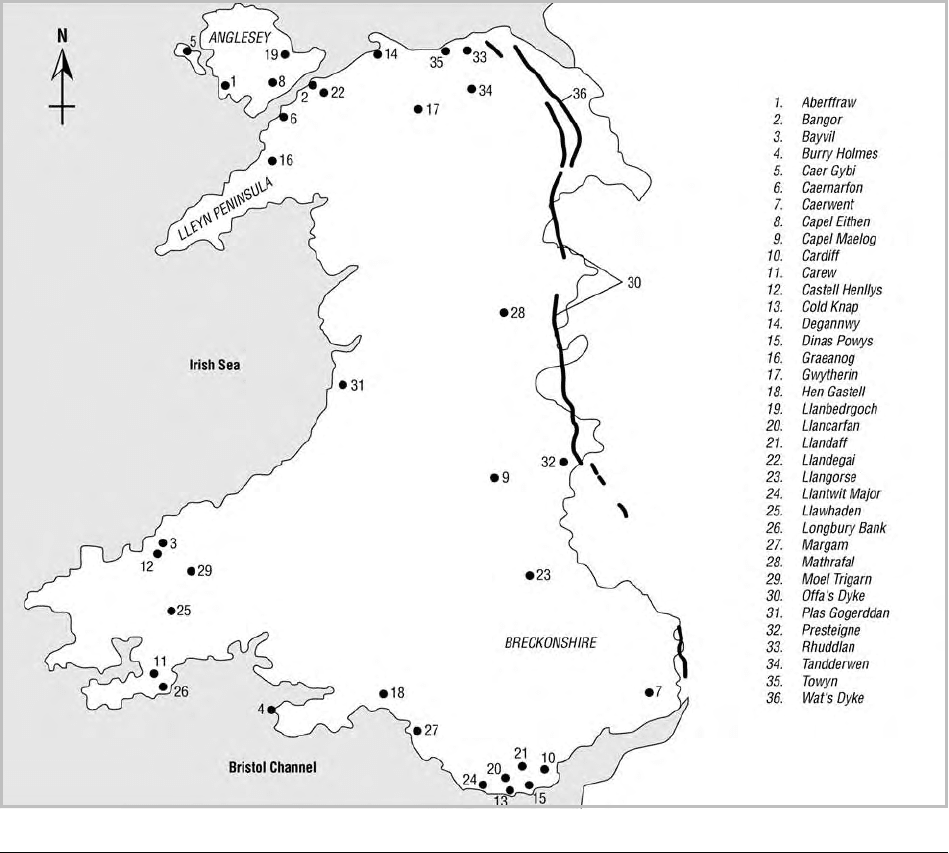

Selected sites in early medieval Wales.

others from the sixth century show clear affiliations

with the Roman world. For some, the tradition of

inscribed stones in Latin was introduced into Wales

from southern Gaul in the fifth century. For others,

they demonstrate a more complex pattern with con-

tinuity of Christianity and Romanitas within Wales,

although with influence from the Continent. The

use of Latin titles such as magistratus on memorials

with crude but clearly Roman-style lettering might

be taken to indicate an administrative structure,

heavily adapted to more uncertain and less central-

ized times but which had aspirations to continue the

traditions or at least the aura of Roman rule. Charles

Thomas has argued that some inscriptions contain

complex messages hidden within them, though this

has been challenged.

IRISH MIGRATIONS

Inscribed memorial stones form the main archaeo-

logical source of evidence for the movement of Irish

population, possibly only an elite, from southern

Ireland to northwestern and particularly southwest-

ern Wales. Documentary sources also support this

interpretation, as do place-name studies. The tribe

that moved to southwestern Wales was the Déisi,

and Thomas has suggested that the Iron Age hillfort

of Moel Trigarn, Pembrokeshire, which was also

EARLY MEDIEVAL WALES

ANCIENT EUROPE

481

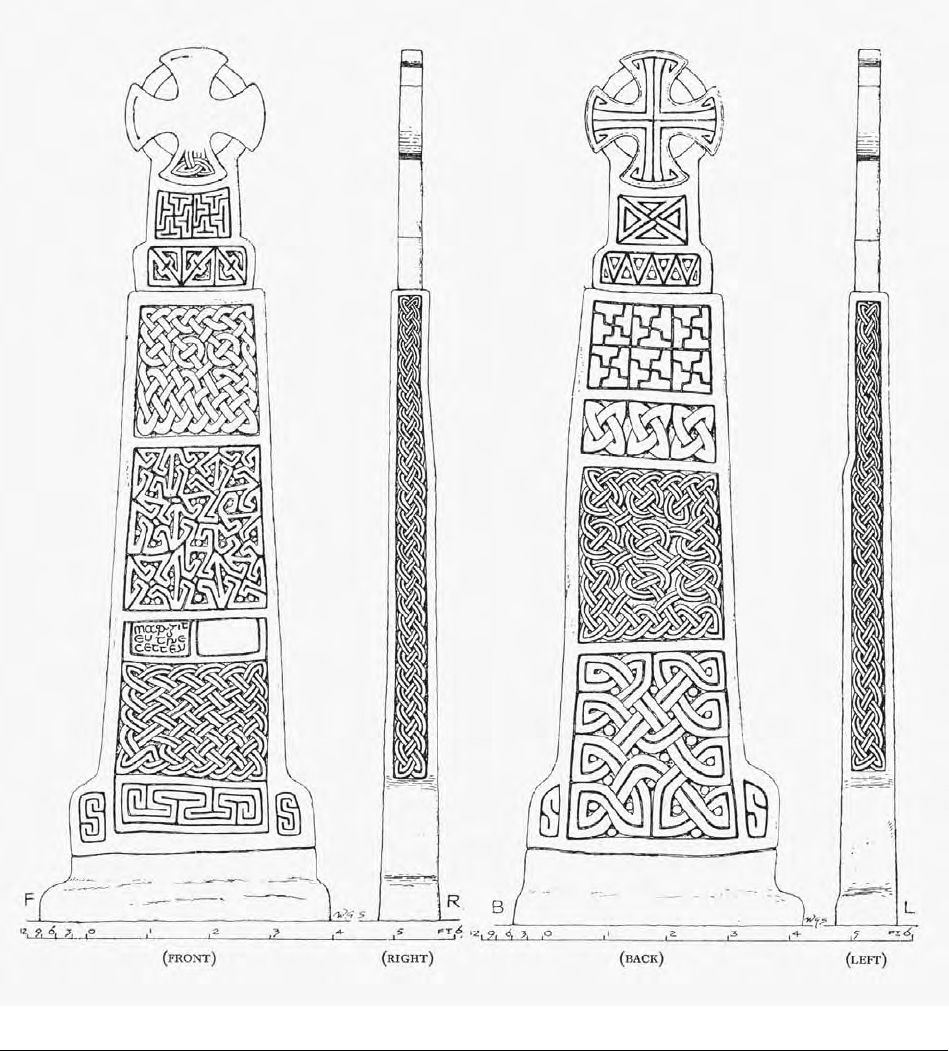

Fig. 1. Early Christian monuments, Wales. FROM NASH-WILLIAMS 1950. © UNIVERSITY OF WALES. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

used in the Roman period, was perhaps their early

base. Excavation at the nearby settlement of Castell

Henllys has identified a late Roman or immediately

post-Roman refortification of an inland promontory

fort. Settlement and control was initially over the

northern part of Pembrokeshire, but subsequently

spread east and south. The date of initial settlement

is uncertain, but it perhaps first began around

A.D.

400.

The earliest inscribed stones are probably those

only in ogham, a style of writing that was first devel-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

482

ANCIENT EUROPE

oped in Ireland, and with Irish words and names.

Later inscriptions, from the later fifth and the sixth

centuries, occur bilingually in ogham and Latin, and

it is during this phase that obvious Christian fea-

tures also occur. Irish and British names can now be

noted, and relationships between individuals (usual-

ly X son of Y) were often recorded.

Less substantial evidence for Irish settlement

has also been found in the Lleyn Peninsula of north-

western Wales, and in Brecknockshire (present-day

Breconshire) in central southern Wales. In Breck-

nockshire, a kingdom of Brycheiniog was carved out

of territory along the river Usk, and the presence of

a number of bilingual inscriptions containing

ogham suggests that this was also linked to Irish set-

tlement. This may have been a secondary movement

from southwestern Wales. Another piece of evi-

dence that suggests an elite link with Ireland, and

one that was continued over generations, is the

presence at Brecknockshire of the only known cran-

nog, an early medieval lake settlement of character-

istically Irish type, in Llangorse Lake. Excavations

there have shown that little survives of the settle-

ment itself, though dendrochronological dates from

planking suggest dates of

A.D. 890 and 893 for at

least one phase of development. Some of the early

medieval artifacts recovered from the silts around

the crannog are probably earlier in date and suggest

a long period of occupation. The finds include items

with a clear Irish origin, such as a pseudo-

penannular brooch fragment and a fragment of a

portable reliquary shrine of the eighth century.

SECULAR SETTLEMENT

A number of sites have been located in Wales that

are considered to be elite secular settlements. The

first of these to be investigated, and the one that has

conditioned interpretations and expectations since,

was that of Dinas Powys. Extensive excavation with-

in the interior of the small inland promontory fort

located slight traces of two rectangular structures

that have been tentatively interpreted as a hall and

barn. Little survived within these buildings, but in

contrast some middens were excavated that provid-

ed rich finds of many kinds.

The early medieval pottery from the site was all

imported; it was identified as belonging to four

major classes, namely A, B, D, and E, and classified

on their form and fabric as defined at the site of Tin-

tagel, Cornwall, where they were first recognized.

Class A pottery at Dinas Powys seems to be of early-

sixth-century Phocaean Red Slip Ware, originally

from the eastern Mediterranean. These fine table-

wares comprised bowls and dishes, one of which

had stamped designs on the interior base. The B

ware sherds were from amphorae vessels, and these

have been further subdivided by subsequent schol-

ars into categories such as Bi and Bii as more re-

search on the forms and fabrics in the Mediterra-

nean has allowed distinctive types with particular

origins to be identified in Britain and Ireland. Dinas

Powys has produced Bi material from the Aegean,

Bii sherds date to the middle or later sixth century

having come from the eastern Mediterranean, and

B Misc, which has not been closely provenanced. In

contrast to these Mediterranean products, there

were also forty-six sherds of D ware in tableware

bowls and in mortaria, mixing bowls of a Roman

tradition. These were probably made in France, per-

haps the Bordeaux region, and were a rare import

to Britain. Dinas Powys also produced Roman-style

bowls, storage jars, and pitchers in E ware of the late

sixth and seventh centuries. E ware may also have

been produced in France.

International contacts are also attested through

the presence of glass, which in the 1980s was the

subject of reassessment. It can now be seen as mate-

rial of Continental origin, but not all from the same

sources that supplied Anglo-Saxon England, sug-

gesting that some came along the same routes as the

imported ceramics.

Leslie Alcock defined Dinas Powys as a llys site,

the residence of a king or prince, based on evidence

from the Welsh Laws, though these only survive in

a later form. The llys formed the central point within

the maerdref, land which supported the llys. These

lands were set within the larger unit, the commote,

and above that was the cantref. This administrative

structure was in use by the end of the period under

consideration here, though its applicability several

centuries earlier is less certain.

The interpretation of Dinas Powys as a high-

status site was based on the presence of exotic im-

ported goods and from the way in which the elites

in less complex stratified societies controlled pro-

duction and distribution of craft products such as

jewelry. The attribution to a llys was additionally

based on the faunal assemblage that was thought to

EARLY MEDIEVAL WALES

ANCIENT EUROPE

483

match what would be expected if the site had been

supplied by food renders as described in the Welsh

Laws. Discoveries in the 1990s found B ware ce-

ramics at the nearby monastery of Llandough,

which might indicate a high-status ecclesiastical site

under the patronage of the Dinas Powys elite. This

pairing of major secular and ecclesiastical sites has

been suggested as a typical pattern, though this has

yet to be firmly demonstrated.

Following the identification of Dinas Powys as

a defended elite site, many other forts were pro-

posed as examples of this type. Few, however, have

produced conclusive evidence, although some such

evidence was recovered below late medieval activity

at the hilltop site of Degannwy, Gwynedd. Excava-

tions at Hen Gastell, Glamorganshire, in the early

1990s have located another such site, heavily dam-

aged by quarrying but displaying a range of sixth-

and seventh-century finds—Bi, and possibly Bii,

amphorae; D and E ware, as well as Continental

glass vessels—on a small hilltop location. Craft ac-

tivity there was demonstrated by the presence of

lumps of fused glass. Documentary evidence hints

that the major political center in the area may have

been at Margam, where a possible secular site and

a definite major monastic site with inscribed monu-

ments have been identified.

Another probable high-status settlement has

been excavated at Longbury Bank, Pembrokeshire.

Again dated to the sixth and seventh centuries by

imported ceramics (Ai, Bi, Bii, Biv, D, and E wares)

and glass, this was an undefended settlement on a

low promontory. This suggests a wider range of

types of high-status sites than previously had been

considered. Structural evidence was limited: one

small building was found, set in a rock-cut platform,

but all other settlement evidence had been de-

stroyed by later agriculture. Craft activity was dem-

onstrated by scrap copper alloy and silver, and also

crucibles, heating trays, and metal droplets. The

early monastic site of Penally lay only 1 kilometer

away, and the secular defended site of Castle Hill,

Tenby, was only 2 kilometers distant. This suggests

that there may have been quite a high density of

these higher-status sites in a region, though they

may have formed networks of functionally distinct

sites used by the same elite group.

Other defended sites such as Carew, Pembroke-

shire, indicate that more of the early elite sites may

often lie beneath later castles, and other site types

undoubtedly await discovery. For example, sand

dunes around the coast contain early medieval arti-

facts in some numbers, suggesting activity there,

and these finds probably represent a category of set-

tlement yet to be revealed through excavation.

Attempts to find later elite residences have not

been successful, with documented high-status sites

at both Mathrafal, Powys, and Aberffraw, Anglesey,

remaining elusive, despite considerable investment

in survey and excavation. Within the boundaries of

the present Principality of Wales lies the Anglo-

Saxon burh at Rhuddlan, with Late Saxon material

culture and structures within an urban context of

the ninth and tenth centuries, although there is no

indication that the native population imitated this

settlement form. Anglo-Saxon occupation spread

across parts of northeastern Wales, and physical

boundaries between the Welsh and the Anglo-

Saxon were defined by the construction of linear

earthworks. Known as Offa’s and Wat’s Dykes, they

have been subject to much detailed survey and lim-

ited excavation beginning in the late 1960s. Al-

though they are extremely difficult to date closely

enough to link with specific historical events, they

probably belong to the later ninth century.

BURIALS

Evidence for burial in Wales comes from a range of

sources. Although the Irish inscribed stones were

memorials, not all may have been set up at the burial

sites themselves, and the overwhelming majority are

now no longer in their original positions. Evidence

has therefore mainly come through casual discover-

ies and archaeological excavations.

Open cemeteries, discovered because of their

adjacency to prehistoric remains including barrows

and standing stones, have been found at several sites

scattered across Wales. The most notable are Capel

Eithen on Anglesey, Llandegai in Gwynedd, Tand-

derwen in Clwyd, and Plas Gogerddan in Cardigan-

shire. Orientation was roughly east-west, though

with a tendency toward a more northeast-southwest

alignment. Bone survival was slight, and so sexing

of the burials was not possible, but the size of the

grave cuts shows that both adults and children were

buried at some sites, though others were just for

adults. Some of the interments had surviving wood-

en coffin stains. A few of the graves were surround-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

484

ANCIENT EUROPE

ed by square structures, but these vary in form with-

in and between sites. Some, such as those at

Tandderwen, were clearly ditches that silted up nat-

urally, and the central area may have been covered

with a mound. In other cases, there were founda-

tions for a building. At Plas Gogerddan a plank-

built structure 4.5 by 3.2 meters could be identi-

fied, with a doorway to the east. At Capel Eithen,

flooring survived within the wooden structure; this

floor sealed the central grave. Graves with rectangu-

lar ditches or structures are also known from south-

ern England, and some Anglo-Saxon graves have

been noted as parallels. Some burial sites in Scotland

also have square barrows, but these seem to be of

a different tradition.

The dating of the cemeteries with the square

enclosures has primarily been through radiocarbon

dating. Coffin stains have been dated approximately

to

A.D. 430–690 and A.D. 770–1050 at Tandder-

wen,

A.D. 265–640 at Plas Gogerddan, and a more

problematic Roman or eighth- or ninth-century

date from Capel Eithen. Clearly, most if not all such

burials date to the early medieval period in Wales,

but more precise chronology for these cemeteries is

still uncertain and so their relationship with church

burial sites cannot be interpreted.

Some other sites have produced evidence of

simple earth-dug inhumation cemeteries, including

ones such as that at the Atlantic Trading Estate,

Barry. This continued from the second century up

to perhaps the tenth century

A.D., and may be the

cemetery for an estate established in the Roman pe-

riod with the same family members using it for gen-

erations.

A particular form of burial that has been identi-

fied for this period in Wales, and which has parallels

in southwestern England, Scotland, and Ireland, is

the long-cist burial, where stone slabs set on edge

have been placed around the edge of the grave and,

in some cases, across the top of the inhumation.

Long-cist burials occur in cemeteries, with the

graves aligned east-west. Many such sites have been

recorded, particularly in southwestern Wales, but

few have been scientifically examined. One at Bay-

vil, Pembrokeshire, was set within an Iron Age en-

closure, and contained numerous long-cist graves,

one dated by radiocarbon to

A.D. 640–883. Later

examples of long-cist graves have been found at

church sites, dated up to the twelfth century, so this

method of burial had a long life and was used in

cemeteries with and without churches.

Relatively few early burials have been found at

church sites, and only at Capel Maelog, Powys, have

extensive excavations allowed a full sequence of site

development to be appreciated. Radiocarbon dates

suggest that burial began there after the seventh

century when a ditch silted up, but unfortunately

only one interment was dated. A coffin stain provid-

ed a sample from the ninth or tenth century

A.D.,

confirming the early medieval date for the burials.

The cemetery was still in use when a church was

built on the site in the late twelfth or early thir-

teenth century. The only other excavated site with

a significant number of early medieval burials is that

of Berlland Bach, Bangor, Gwynedd. A total of sev-

enty-eight burials have been found; they varied

slightly in orientation, and this may relate to their

date.

THE CHURCH

Many churches that became part of the parochial

system in the Norman period may have been built

during the early medieval period. The only early

standing fabric from Wales is at Presteigne, Powys,

but as the surviving fragments of nave and chancel

arch are in the Anglo-Saxon style, they provide no

indication of native Welsh ecclesiastical architec-

ture. Wooden churches were probably the normal

construction, but only a tiny example at Burry

Holmes, Glamorgan, has been excavated. This

building was only about 3.4 meters by 3.1 meters

and so would be very comparable with timber ora-

tory churches excavated in Ireland and southwest-

ern Scotland.

Inscribed stones from the sixth century onward

indicate Christian features not only in the use of the

Latin phrase hic iacet, “here lies,” which occurs else-

where in Gaul in Christian contexts, but also by def-

inite Christian symbolism. Notable examples in-

clude simple crosses with various terminals for the

arms, ringed crosses, Chi-Rho symbols (Christo-

grams), and some ringed crosses that resemble a fla-

bellum or liturgical fan. Many of these designs can

be paralleled in Ireland but that may reflect designs

inspired from a common, shared Christian material

culture and documentation in Britain, Ireland, and

Gaul than on direct copying from one primary

source. Historical sources indicate considerable

EARLY MEDIEVAL WALES

ANCIENT EUROPE

485

movement of religious personnel within and be-

tween these regions, and indeed to other parts of

Europe. V. E. Nash-Williams attempted a classifica-

tion and termed the simple designs associated with

ogham and Latin as class 1. Later inscriptions were

decorated with various forms of a cross, and some

had inscriptions carved with half-uncial style letter-

ing, derived from seventh-century and later manu-

script writing; these are termed class 2. The inscrip-

tions are in Latin, with the one exception at Towyn,

Merionethshire, which is the earliest surviving ex-

ample of the written Welsh language.

The latest group of stone sculpture, the class 3

memorials, was carved beginning in the ninth cen-

tury and continuing until the eleventh century.

These are mainly found in southern Wales, where a

range of styles is found, with few examples in north-

ern Wales. The class 3 monuments have more elab-

orate carving than the earlier stones and can be

broadly divided into pillar crosses, slab crosses, and

cross slabs. Figure representation is rare on the

Welsh monuments, and occurs almost completely in

the southeast. The main design features were inter-

lace, fret, and key patterns. Though never matching

the quality of design and execution of the fine high

crosses of Ireland and Scotland, some were substan-

tial monuments.

Many of the early inscribed stones discussed

above are now found at ecclesiastical sites, and some

may have been erected there. Others, however, have

been moved into churches and churchyards in rela-

tively recent times, and so the presence of stones

alone does not necessarily indicate an early church

site. The likely sites of early churches are suggested

by several other features occurring together, such as

the use of early saints’ names, the presence of a holy

spring or well, and a circular or oval churchyard.

Some of the major sites can also be linked with doc-

umentary references. Aerial photography, particu-

larly in southwestern Wales, has highlighted the

presence of outer concentric enclosures around

many subcircular churchyards, suggesting possible

continuity of late prehistoric and Roman period sec-

ular settlements, perhaps given to the church in the

early medieval period. These arrangements are also

highly reminiscent of some of the concentric enclo-

sures found on Irish monastic sites. As yet there has

been insufficient excavation on Welsh sites of this

type to determine more regarding their detailed

chronology and functions.

Unlike contemporary Ireland, Wales possessed

no large monasteries endowed with impressive

stone structures. Although there was some sculp-

ture, even this was limited in quantity and quality.

Welsh monasteries did contain some small stone

buildings, and such institutions owned some relics

and libraries, but little survives. A small fragment of

a reliquary casket from Gwytherin, Denbighshire, is

similar to those surviving in some numbers from

Ireland. Fragments of another shrine have been ex-

cavated from Llangorse crannog, Brecknockshire,

even though that is a secular site.

Welsh monasteries appear relatively impover-

ished compared with the equivalent contemporary

establishments in Ireland and Scotland. This may

relate to the relative wealth of such regions, but

other factors may have played their part. Welsh cul-

tural expectations were probably that surpluses

should be devoted to feasting and almsgiving rather

than used for heavy investment in material culture

that could be displayed as part of social competition

and so survive for archaeological study today. Of

particular interest are sculptured crosses of class 3,

which, although not numerous and of inferior qual-

ity compared with Irish and Scottish high crosses,

nevertheless provide evidence for ecclesiastical

workshops and patronage.

Written sources late in the early medieval period

in Wales survive in some numbers for southeastern

Wales, and have been the subject of much scholar-

ship since the 1970s, particularly concerning the

charters associated with Llandaff. These demon-

strate how Llandaff, and by analogy other successful

ecclesiatical sites, became substantial landowners

with estates that provided manpower and agricul-

tural produce. Llandaff gained most of its land in

the eighth century, and Wendy Davies suggests that

this may have been when estates, which had contin-

ued intact from the late Roman period, were finally

broken up and royalty lost their control of dona-

tions to religious houses. At this writing, however,

no evidence has come to light that would demon-

strate a material shift in ecclesiastical investment in

buildings or sculpture at that time.

Scholarship in archaeology and history since the

1990s has highlighted the fact that a Celtic church,

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

486

ANCIENT EUROPE

distinct from Continental and Anglo-Saxon tradi-

tions, never existed. Many administrative powers

were held by bishops, though monasteries could be

powerful entities. In Wales there could even be

some federations of monasteries and dependent

churches, as with those linked to Llancarfan, Gla-

morganshire, but such features also occurred else-

where in the Christian west. The idea of a Celtic

church or a distinctive Celtic Christianity is there-

fore a modern invention.

VIKING INCURSIONS

Viking raids around the coast of Wales took place in

the late tenth and the eleventh centuries and affect-

ed monastic establishments in the north, west, and

south. A small number of Viking burials have been

found, all close to the coast. There were, however,

a few Viking settlements, and one was excavated at

Llanbedrgoch, Anglesey, in the 1990s. Building 1

of the tenth century was a house 11 meters long and

5 meters wide, with a clear domestic area in the

northern part of the structure, with a central hearth

and bench or bed areas around the sides. A wide

range of artifacts have been recovered from the site,

including Hiberno-Norse style artifacts, probably

from Viking Dublin, such as ringed pins and an

arm-ring trial piece. The Vikings in Wales formed

part of a complex network of trading and political

links that were built around the two powerful cen-

ters of Dublin and York.

CONCLUSIONS

The pattern of adaptation following the collapse of

Roman administration, and the movement of war-

rior elites to take advantage of any instability seen

in Wales, can be paralleled elsewhere in post-Roman

Britain. The development of a series of small king-

doms ruled from relatively small but sometimes de-

fended settlements, and linked with ecclesiastical

sites established out of patronage, can also be paral-

leled in Ireland and western Britain. There were,

however, distinctive features of the Welsh experi-

ence in this period, even if these tended toward

small-scale solutions that seem unimpressive in ar-

chaeological terms. Monasteries never became large

centers, and the secular political structure did not

become centralized. Expression through material

culture never became a cultural strategy, giving the

impression that Wales was poorer than it probably

was. Only with the coming of the Anglo-Normans

did monumental construction—in castles, church-

es, monasteries, and planned towns—become an ac-

tive strategy in Wales, with dramatic remains that

now dominate the landscape.

See also Hillforts (vol. 2, part 6); Viking York (vol. 2,

part 7); Raths, Crannogs, and Cashels (vol. 2, part

7); Viking Dublin (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alcock, Leslie. Economy, Society and Warfare among the

Britons and Saxons. Cardiff: University of Wales Press,

1987. (Updated and expanded version of Alcock

1963.)

———. Dinas Powys. Cardiff: University of Wales Press,

1963.

Brassil, K. D., W. G. Owen, and W. J. Britnell. “Prehistoric

and Early Medieval Cemeteries at Tandderwen, near

Denbigh, Clwyd.” Archaeological Journal 148 (1991):

46–97.

Britnell, W. “Capel Maelog, Llandrindod Wells, Powys: Ex-

cavations 1984–1987.” Medieval Archaeology 34

(1990): 27–96.

Campbell, Ewan, and Alan Lane. “Excavations at Longbury

Bank, Dyfed, and Early Medieval Settlement in South

Wales.” Medieval Archaeology 37 (1993): 15–77.

Davies, Wendy. Wales in the Early Middle Ages. Leicester,

U.K.: Leicester University Press, 1982. (A comprehen-

sive review by a historian who integrates archaeological

evidence effectively.)

Edwards, Nancy, and Alan Lane, eds. The Early Church in

Wales and the West. Oxbow Monograph 16. Oxford:

Oxbow, 1992. (A collection of papers by specialists on

various aspects of history and archaeology.)

Murphy, Ken. “Plas Gogerddan, Dyfed: A Multi-Period

Burial and Ritual Site.” Archaeological Journal 149

(1992): 1–38.

Mytum, Harold. The Origins of Early Christian Ireland.

London: Routledge, 1992. (One section of the book

considers the migration of Irish to Wales and the impact

of this contact on stimulating change in Ireland.)

Nash-Williams, V. E. The Early Christian Monuments of

Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1950. (The

classic work on the stone inscriptions and sculpture,

with a detailed catalog and many line drawings; it is due

to be replaced by a completely reworked study by

Nancy Edwards.)

Quinnell, H., M. Blockley, and P. Berridge. Excavations at

Rhuddlan, Clwyd: 1969–1973: Mesolithic to Medieval.

CBA Research Report, no. 95. London: Council for

British Archaeology, 1994.

Redknap, Mark. Vikings in Wales. An Archaeological Quest.

Cardiff: National Museums and Galleries of Wales,

EARLY MEDIEVAL WALES

ANCIENT EUROPE

487

2000. (A popular account covering many aspects of Vi-

king Age Wales with abundant color illustrations.)

Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments

in Wales. An Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of

Glamorgan. Vol. 1, part 3, The Early Christian Period.

London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1976.

Thomas, Charles. Christian Celts: Messages and Images.

Stroud, U.K.: Tempus, 1998. (A controversial account

of the inscriptions and their possible hidden meanings.

For a substantial critique, see H. McKee and J. McKee,

“Counter Arguments and Numerical Patterns in Early

Celtic Inscriptions: A Re-examination of Christian

Celts: Messages and Images,“ Medieval Archaeology 46

[2002]: 29–40.)

———. And Shall These Stones Speak? Post-Roman Inscrip-

tions in Western Britain. Cardiff: University of Wales

Press, 1994. (A detailed analysis of the inscriptions and

their archaeological and historical implications.)

———. Celtic Britain. London: Thames and Hudson,

1986. (A popular, well-illustrated account covering

Cornwall, southwestern England, and Scotland as well

as Wales, and so sets Wales in context.)

Wilkinson, P. F. “Excavations at Hen Gastell, Briton Ferry,

West Glamorgan, 1991–1992.” Medieval Archaeology

39 (1995): 1–50.

Williams, George, and Harold Mytum. Llawhaden, Dyfed:

Excavations on a Group of Small Defended Enclosures,

1980–1984. BAR British Series, no. 275. Oxford: Brit-

ish Archaeological Reports, 1998.

H

AROLD MYTUM

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

488

ANCIENT EUROPE

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

ANGLO-SAXON ENGLAND

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAYS ON:

Spong Hill . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 496

Sutton Hoo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 498

West Stow . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 500

Winchester . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 501

■

From an Anglo-Saxon monk, the Venerable Bede

(

A.D. 673–735), comes the traditional portrayal of

the downfall of Roman Britain and the beginnings

of early Anglo-Saxon England. Written in the first

third of the eighth century, Bede’s Ecclesiastical

History of the English People (Historia ecclesiastica

gentis Anglorum) was drawn in part from On the

Fall of Britain (De excidio Britanniae et conquestu),

a polemical sermon by the sixth-century British cler-

ic, Gildas. Supplementary accounts of the arrival of

the Anglo-Saxons come from a ninth-century revi-

sion accredited to the Welsh monk Nennius, the

late-ninth-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and brief

references in continental documents.

These sources present a cataclysmic history of

battle and bloodshed. According to their account,

Roman military forces were withdrawn from the

province in the early fifth century, leaving the Brit-

ons to defend themselves against barbarian attacks.

The Picts and Scots soon after recommenced their

raids and were so successful that the Britons called

in vain upon the Roman commander in Gaul to aid

the native defenses. Although abandoned, the Brit-

ish rallied and overthrew the enemy forces. After a

period of peace, ominous rumors led the Britons to

hold council over enemy attacks. The head of the

Britons’ council, Vortigern, then invited the Saxons

of northern Germany to protect them. Led by

Hengist and Horsa, three ships bearing Saxons ar-

rived on the English coast. The number of Saxons

multiplied and, in time, a quarrel about compensa-

tion arose between the Saxon warriors and their

British overlords. The Saxons rebelled and, during

the ensuing destruction, the Britons fled to the safe-

ty of the western forests and mountains. The tide of

Saxon conquest was halted by the British victory at

Mons Badonicus. From the time of that battle to

the writing of De excidio Britanniae et conquestu,

relations between the two groups remained peace-

ful.

EARLIEST EVIDENCE

The traditional image of the transition from Roman

Britain to early Anglo-Saxon England as a period of

turmoil and warfare has been supplanted by a more

complex and modulated conception of culture

change. The eighth- and ninth-century written ac-

counts of the fifth- and sixth-century preliterate

Anglo-Saxon past are not always believable, as they

incorporate fantastic characters and events and in-

ANCIENT EUROPE

489

vented chronologies. No longer is the Anglo-Saxon

invasion viewed as a single event. Ceramics, belt fit-

tings, and dress ornaments indicate that Germanic

people were entering Britain prior to the fifth-

century dates calculated from the documentary

sources. The lands bordering the North Sea exhibit

the earliest archaeological evidence for a Germanic

presence in late Roman Britain. Germanic merce-

naries in the Roman army were garrisoned at coastal

forts and inland towns. The withdrawal of Roman

military support from the province in the early fifth

century was closely followed by the middle of the

fifth century with the appearance of Germanic-style

cemeteries. Continental parallels argue for the sub-

sequent immigration into eastern England in the

sixth century of people from southern Norway.

The size and character of Germanic populations

engaged in this transition remains contested. Some

archaeologists argue that a few warrior bands from

northern Germany and southern Scandinavia seized

control of regional British polities while others con-

sider the discontinuities in material culture and lan-

guage as evidence of large-scale migration. The lack

of any clear continuity of urban life and the evidence

for a breakdown in the rural villa system from the

Roman to the Anglo-Saxon period indicates a dislo-

cation of the economic structure. Likewise, the re-

placement of Celtic dialects with Old English

speech and the renaming of the landscape with Old

English place names indicate extensive Anglo-Saxon

settlement. Although the extent and character of

British continuity is contested, British kingdoms

survived in the highland zone, Wales, and the

southwest. Some of these kingdoms, such as Elmet,

which lost its autonomy to the Anglo-Saxon king

Edwin of Northumbria in 617, were subsumed in

the process of political centralization. Recognition

that in early medieval Europe ethnic identity was

fluid and situational has called for a reassessment of

the extent and character of native British survival

and assimilation. Indeed, no single model adequate-

ly accommodates the regional variability now recog-

nized during the settlement period.

CEMETERIES

Early Anglo-Saxon England remains best known ar-

chaeologically through more than one thousand

cemeteries, many of which were unsystematically

excavated during the eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries. Unfortunately, the relationship between

cemeteries and the settlements that they served is

poorly understood, as few excavations include both

types of evidence. However, at Mucking (Essex)

and West Heslerton (Yorkshire), the settlements

display a structural uniformity that implies a social

equality not apparent in the diverse burial assem-

blages of the adjacent cemeteries.

During the early Anglo-Saxon period (c. 450–c.

650), two main burial practices predominated: cre-

mation and inhumation. Cremation required burn-

ing the dressed body of the deceased on a pyre. A

selection of the burned bone, generally from the

head and chest, was then buried either directly into

the earth or enclosed in a ceramic urn, or more rare-

ly, a metal, cloth, or leather container prior to inter-

ment. Miniature toilet implements, perhaps serving

as symbolic substitutes for the full-scale items, were

occasionally included with the cremated bone. Cre-

mation pits, sometimes marked by stones, con-

tained a single deposit or a cluster of vessels. Wood-

en post-built structures, perhaps housing the

cremated remains of a family grouping, have been

identified at Apple Down (Sussex) and Berinsfield

(Oxfordshire).

Inhumation burials required the dressed but

unburned body to be deposited into a rectangular,

often wood- or stone-lined pit. Rarely, an elaborate

wooden chamber, as at Spong Hill (Norfolk), or a

boat, as at Snape (Suffolk) or at Sutton Hoo (Suf-

folk), was incorporated into the burial structure. At

some sites, such as Spong Hill and Morningthorpe

(Norfolk), ring ditches enclosed a number of

graves. The dead were furnished with weaponry,

drinking and eating paraphernalia, foodstuffs, and

tools, and in some cases were covered with plant

fronds, animal hide, or fabric.

During the course of the sixth century, burial in

large cremation cemeteries, such as Elsham (Lin-

colnshire) and Newark (Nottinghamshire) was gen-

erally replaced by the use of numerous smaller pre-

dominantly inhumation graveyards, such as

Welbeck Hill in Irby-on-Humber (Lincolnshire)

and Fonaby (Lincolnshire). The trend toward smal-

ler inhumation cemeteries may reflect a change in

the sense of group cohesion from membership with-

in a larger quasi-ethnic group to membership within

a localized community or may reflect the waning of

ancestral claims to community identity. However,

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

490

ANCIENT EUROPE