Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ern part of the West Highland coast, and retained

close ties with their Irish homeland. The other

group was the Northumbrian Angles, based at Bam-

burgh on the northeastern coast of England by the

mid–sixth century. The Angles expanded their con-

trol over the kingdom of Gododdin by the seventh

century and over Rheged, in the southwest of Scot-

land, by the eighth century, leaving Strathclyde as

the only remaining autonomous British kingdom.

The intrusiveness of these groups has long been

emphasized by historical tradition, but archaeology

warns against exaggerating the differences among

the Brittonic Britons and Picts, the Gaelic Scots,

and the Germanic Angles. Despite their linguistic

differences, the economies and material cultures of

these groups were very similar. All of them relied on

mixed farming, where cattle were the most impor-

tant livestock, followed by sheep and pigs; barley

and oats were the principal crops; and along Scot-

land’s convoluted coast, fish and sea mammals also

were important resources. Most people would have

lived on isolated farmsteads or in small, self-

sufficient hamlets—there was nothing resembling

an urban center in Scotland until the twelfth centu-

ry. Pottery was uncommon in most of Scotland dur-

ing this period, and most metal would have been re-

cycled. But excavations at waterlogged sites have

produced a wide range of wooden vessels and other

organic artifacts.

The scarcity of well-preserved artifacts has left

Scottish archaeologists precious little to work with

and accounts for the lack of a well-defined chronol-

ogy for much of later prehistory and the early medi-

eval period until the advent of radiocarbon dating

in the mid–twentieth century. The artifacts that are

useful for dating, usually because of their wider cul-

tural milieu, were high-status objects: fine metal-

work, imported pottery, and sculpture—items asso-

ciated with the elite rather than with ordinary

members of society. Consequently much early me-

dieval archaeology has concentrated on high-status

sites, such as fortified settlements and religious cen-

ters, although rescue excavations in advance of de-

velopment or coastal erosion are providing more ev-

idence for the lower classes of early medieval

society.

It is important to recognize this bias toward the

upper classes not only because it is mirrored in the

historical sources (written by and for elites) but also

because these were precisely the people most likely

to be defining ethnicity in ways advantageous to

their own position in the competition for power.

Historical, art historical, and archaeological evi-

dence illustrates the ease with which northern Brit-

ish elites mixed and mingled, in political marriage

alliances and exile as much as on the battlefield, re-

gardless of linguistic or religious differences. A well-

documented example is when Æthelfrith, king of

the Angles (r. c.

A.D. 592–616), was killed. His sons

took refuge in other kingdoms. Oswald (r.

A.D.

634–641) went to Dál Riata, and Oswiu (r.

A.D.

641–670) married into Irish and British royal hous-

es as well as that of their Northumbrian rival. Ean-

frith (r.

A.D. 633) had a son who reigned as a king

of the Picts. All three were converted to Christianity

while in exile, although Eanfrith is reported to have

reverted to paganism during his brief reign, and

Oswald imported Columban Christianity into his

kingdom from Dalriadic Iona with the foundation

of Lindisfarne. It was within these dynamic cross-

cultural contexts that the Insular art style devel-

oped, and it should serve as a warning against the

use of simplistic ethnic labels for things as well as

people during the early medieval period.

SETTLEMENTS

While the elites were participating in an increasingly

shared and internationally connected culture, there

are regional differences in the archaeological record,

particularly in settlements. In the south, among the

British and Angles, slightly different forms of rec-

tangular post-in-ground timber halls have been ex-

cavated on such sites as Doon Hill in the east and

Whithorn in the west, some defended by palisades;

similar forms appear to have been used by the

southern Picts. (This thinking is based largely on

the evidence of crop marks and soil marks visible in

aerial photographs, however, and excavation is

needed to confirm the dates of these structures.

One such hall, believed to be early medieval, turned

out to be three thousand years too old.) In the west,

among the Britons and the Scots, are crannogs—

natural or modified islands, usually with round tim-

ber and wattle houses. These are considered defend-

ed settlements because of the water barrier, and ex-

amples such as Buiston and Loch Glashan were

high-status sites. Along the West Highland coast

and in the Northern Isles, duns and brochs, large

round drystone structures built in the Late Iron

DARK AGE/EARLY MEDIEVAL SCOTLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

471

Age, were reoccupied, often with modifications, or

cannibalized for the construction of more modest

cellular or figure-of-eight houses. Figure-of-eight

houses have been found from the Orkneys to Coun-

ty Antrim, Ireland, illustrating the wide spread of

some elements of material culture. It is well to re-

member that the Picts and Scots were allies against

the Romans, and both could assemble substantial

fleets of ships, which would have been used to sail

between the islands during peace as well as war.

The promontory fort at Burghead, in the north-

east, is the largest fortified site of this period in Scot-

land, and it overlooks an excellent harbor. At least

thirty stones carved with Pictish bull symbols were

found there, and the wooden framework for its tim-

ber-laced ramparts was fastened with nails. The only

other known example of nailed timber-laced ram-

parts is at Dundurn, another Pictish stronghold.

Dundurn is a nuclear fort: it has a small citadel at the

summit of a hill, with annexes built wherever the hill

is relatively level. Britons and Scots as well as Picts

used nuclear forts; the type site is Dunadd, the capi-

tal of Dál Riata. Fortified sites such as these forts

and crannogs would have been the residences of

royalty, and these sites have produced evidence for

specialized craft working, particularly the produc-

tion of fine metalwork, suggesting that smiths

worked under the patronage or control of kings and

other nobles.

ARTIFACTS

Fine metalwork constitutes one of the more distinc-

tive classes of artifacts from early medieval Scotland,

like the highly ornamented Hunterston brooch, a

pseudo-penannular brooch, one that looks as if it

has a gap in the ring, which would be a penannular

brooch, but does not. While the Angles have more

bow brooches (essentially highly elaborate safety

pins), the Celtic groups favored hand pins (large

straight pins) and penannular brooches (circular

forms with a gap for the pin to pass through). These

pins were made of silver or bronze, and some were

decorated with gold, enamel, and semiprecious

stones or glass. The brooches and pins themselves

are rare survivals, and many were chance finds made

before the twentieth century. This limits their value

as archaeological evidence, but there is lively debate

among art historians regarding the origins of differ-

ent styles, the sources of various decorative ele-

ments, and the social functions of such rich objects.

Increasingly these finds are supplemented by the re-

covery of the molds used to make such objects from

sites like the Mote of Mark in the southwest (late

sixth century to early seventh century) or Dunadd

(seventh century). They can establish conclusively

that a particular type was made at a specific place

during a given time period.

A larger number of high-status sites have pro-

duced small quantities of imported pottery and glass

vessel fragments. This material falls into two catego-

ries: imports from the Mediterranean dated from

the later fifth century to the mid-sixth century and

imports from western France dated from the sixth

through the seventh centuries. The Mediterranean

pottery includes African red slip tableware from Tu-

nisia (A ware), which has been found at Whithorn

and Iona, and several types of amphorae (B ware),

the earlier forms from the eastern Mediterranean

and the later ones from Tunisia. The amphorae

would have been shipping containers for commodi-

ties like wine or olive oil, and the only other site in

Scotland where they have been found is Dumbarton

Rock, the capital of Strathclyde. While most of these

Mediterranean imports have been found in South-

west Britain and the Scottish examples are best seen

as outliers, that is not the case for the later French

imports, known as D ware and E ware. D ware is a

derivative form of late Roman tableware, dating to

the earlier sixth century, and has been found at

Dunadd, the Mote of Mark, and Whithorn. E ware

is a hard, gritty ware that, like the earlier amphorae,

probably was a container. It dates from the late sixth

century and possibly into the early eighth century,

but most examples in Scotland have been found in

contexts dating to the first half of the seventh centu-

ry. More of this ware has been found in Scotland

than anywhere else in the British Isles; Dunadd has

the largest collection and Whithorn the second larg-

est, and it has been discovered on at least thirteen

other sites, including a couple in the Pictish east.

SCULPTURE

The Picts are associated more commonly with a very

distinctive art tradition found mainly on stone—the

famous Pictish symbol stones. More than fifty dif-

ferent symbols are known: highly naturalistic figures

of animals; recognizable objects, such as combs and

mirrors; and abstract figures, the most common

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

472

ANCIENT EUROPE

symbols being the double disk and crescent, often

overlain by linear symbols known as Z-rods and V-

rods. The meanings of the symbols and the func-

tions of the stones are a matter of perennial debate;

a writing system, totems, marks of rank or occupa-

tion, territorial or alliance markers, or memorials

for important events or the dead have all been sug-

gested.

Class I stones, where the symbols usually are in-

cised into undressed stone, are believed to date to

the sixth and seventh centuries and perhaps earlier

and are concentrated in Northeast Scotland. The

stones with bulls from Burghead are Class I, and

there is evidence that others were associated with

burials. The only Pictish carving in Dalriadic territo-

ry is a Class I boar carved into the bedrock at

Dunadd, which has fueled debate about who was

overlord over whom and when. Class II stones,

where the symbols typically are carved in relief and

accompanied by Christian motifs and scenes of elite

activities, such as hunting and war, date to the late

seventh century and early eighth century and have

been found primarily in southern Pictland. The

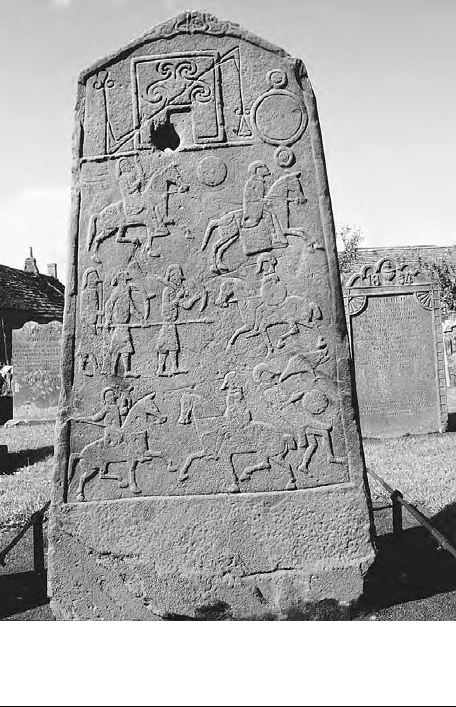

Aberlemno Kirkyard (Churchyard) stone is a Class

II stone: it has an interlace-decorated cross on the

front, while the reverse shows an extraordinary bat-

tle scene with Pictish symbols in relief above (fig. 1).

It has been suggested that this stone commemo-

rates the battle of Nechtansmere (Dunnichen),

which was fought nearby in

A.D. 685, where the

Picts defeated the Angles and killed their king,

Oswiu’s son Ecgfrith (r.

A.D. 670–685), ending An-

glian expansion to the north. Secular scenes from

these stones have given the clearest images of the

people of early medieval Scotland: men armed for

war, riding after stags, and drinking from horns; a

woman with a large penannular brooch riding side-

saddle with a man on horseback barely visible be-

hind her; and hooded clerics with crosiers.

In Dál Riata to the west there was a different

sculptural tradition and a distinctive form of inscrip-

tion used primarily on stone. The Scots were re-

sponsible for bringing the ogham script, where

short slashes are incised across a baseline, from Ire-

land, and ogham subsequently was adopted by the

Picts. Inscriptions in this style date from the sixth to

tenth centuries, but they are difficult to transcribe

and translate; few can be read, even by experts.

More than 450 early medieval carved stones have

Fig. 1. Battle scene on the cross-slab at Aberlemno

churchyard. © CROWN COPYRIGHT. REPRODUCED COURTESY OF

HISTORIC SCOTLAND.

been recorded in Argyll, about a hundred from

Iona, but many are very simple crosses and difficult

to date with certainty. Most attention is given to the

elaborately carved crosses that date to the second

half of the eighth century, such as Saint Oran’s,

Saint John’s, and Saint Martin’s crosses at Iona and

the Kildalton cross on Islay. This sculpture almost

always is associated with religious sites, and there is

little evidence comparable to the hunting scenes on

the Pictish stones to suggest that it was an impor-

tant way for secular elites to display their status. As

with the Pictish stones, however, many of the deco-

rative elements on these monuments are shared

with the Insular art tradition as it appears on fine

metalwork and in Gospel books, such as the Book

of Durrow or the Book of Kells. It is now thought

that the latter two were created at Iona, which illu-

minates the interaction between the secular and reli-

gious spheres as well as between the different ethnic

groups during this time.

DARK AGE/EARLY MEDIEVAL SCOTLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

473

RELIGION

The expansion of Christianity across Scotland dur-

ing this period also has been a topic of continuing

scholarly interest. It was Christianity that promoted

the literacy that produced the earliest indigenous in-

scriptions and documents, and even in the post-

Roman period some Britons were Christian. The

Scots were Christians by the time they were histori-

cally active in Argyll, and it was to Dál Riata that

Saint Columba came in

A.D. 563, founding the

monastery of Iona shortly afterward. While Colum-

ba’s Life shows him visiting the pagan king of the

northern Picts, there is little evidence for explicitly

missionary efforts. Nevertheless both the Angles

and the Picts had adopted Columban Christianity

before those groups switched to the Roman date for

Easter, the Angles in the late seventh century and

the Picts in the early eighth century.

Little structural evidence for churches in Scot-

land has survived, except for Whithorn. In many

cases these sites remain in use, and later construc-

tion has obliterated the remains of the earliest foun-

dations, although ongoing excavations at Port-

mahomack, which appears to have been a monastery

during the eighth and ninth centuries, will provide

better evidence for the Pictish northeast. At Iona

part of the vallum—the bank and ditch that separat-

ed the religious community from the secular

world—survives, but texts reveal that the buildings

within were built of timber and wattle, which has

left no clear trace. Building churches of wood ap-

parently was part of the Irish Columban tradition,

although hermits’ refuges usually had small, round

drystone cells; it was the Roman tradition that en-

couraged stone construction. In the absence of sur-

viving structural remains, the presence of early

churches typically is indicated by place-name evi-

dence—eccles- names in British territory and kil-

names in Dál Riata.

Burials have little to contribute to an under-

standing of the early historic phase. First of all, the

acid soils of Scotland have destroyed most of the

skeletal remains. Second, burial practices were quite

similar among the different groups, both before and

after the adoption of Christianity. Even in the Late

Iron Age the most usual rite was extended inhuma-

tion in either a simple grave or a long cist, where

stone slabs form a rough coffin, without grave

goods. The only identifiable characteristic for Chris-

tian graves therefore is their east–west orientation.

Some Picts did place such graves under low mounds

with square stone kerbs (curbs) in the early medieval

period. But most such monuments are known only

from aerial photographs, and more excavation is

needed to confirm the dates.

VIKING PERIOD

At this point a fifth group and sixth language en-

tered Scotland: the Vikings. Unlike the evidence for

the Angles and Scots, historical sources provide a

definite date for their arrival, for one of the earliest

references to these “gentiles” is of their raid on Iona

in

A.D. 795. By the mid-ninth century the Norse

were moving in, rather than making hit-and-run

raids, almost entirely in the Northern and Western

Isles, which were conveniently placed on the island-

hopping sea route from western Norway to Ireland.

The intensity of Norse settlement is shown by place

names, and in the Northern Isles and northern

mainland the local language was replaced by Norn,

a dialect of Norwegian. The Scandinavian place-

names of Southwest Scotland, however, are not re-

lated to this land taking but instead are evidence for

settlement during the twelfth century from north-

ern England.

The most alien thing about these Galls, or “for-

eigners,” to the people of early medieval Scotland

was their pagan religion—which is why they had no

scruples about plundering churches and taking

Christians as slaves. The archaeological record pro-

vides ample evidence of this in the form of furnished

graves for both men and women: the men were bur-

ied with their weapons and sometimes with horses

or merchants’ scales and the women with character-

istic oval “tortoiseshell” brooches and tools for

making linen. In a few cases men and women have

been found buried in small clinker-built boats.

These graves provide the best evidence for a dis-

tinctly Norse material culture. This is important, be-

cause on many sites where rectangular Norse long-

house forms replace earlier Pictish cellular structures

are found a mix of Pictish and Norse artifact types

and even bilingual runic inscriptions. These finds

imply that local populations survived, whether as

slaves, an underclass below Norse elites, or perhaps

as allies and collaborators.

By the late ninth century the Northern Isles

were the base of the powerful earls of Orkney, origi-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

474

ANCIENT EUROPE

nally from western Norway; by the late tenth centu-

ry, when they were officially converted to Christian-

ity, their sphere of political control included

Shetland, the northern mainland, and the Western

Isles. Most of the Viking hoards found in Scotland,

which include Arabic coins, ring money (small, ir-

regular silver rings used as a form of currency by the

Vikings), and hack silver (pieces of silver cut from

larger objects used for the same purpose), date to

this later period, from the mid–tenth century into

the early eleventh century. Unlike hoards of reli-

gious and secular fine metalwork from the earlier

period, such as the Saint Ninian’s Isle treasure from

Shetland, these pieces would have been associated

more closely with trading than raiding.

It has been suggested that the hogback monu-

ments found in southern Scotland and dating to the

tenth and early eleventh centuries marked the

graves of Scandinavian traders from northern En-

gland. Once they had become Christians and sub-

scribed to broadly shared cultural values, Scandina-

vians were simply one more element in Scotland’s

multicultural mix. The Hunterston brooch men-

tioned above, a high-status object, has a runic in-

scription: “Melbrigda owns [this] brooch.” The

language is Norse, yet Melbrigda is a Celtic name.

CREATING “SCOT-LAND”

While past historians cast the early medieval period

as a time of war between monolithic ethnic groups

for control over what would become Scotland, with

the Dalriadic Scots as the winners, archaeology has

shown that the situation was much more complicat-

ed and has highlighted the ways in which the differ-

ent groups contributed to the process of forging a

common culture. If there is a large-scale notable

trend throughout this period, it is increasing socio-

political centralization. In the Roman period

sources attest to a multiplicity of Pictish tribes; by

the early historic phase there are probably three sig-

nificant Pictish political groups. The hierarchical le-

vels of kingship are evident in Dál Riata, with kings

of kindreds, the most powerful of them the Dal-

riadic overking, and the overkings of the Scots, An-

gles, and Picts competing for the position of “high

king” of northern Britain during the early historic

phase. It was only in the Viking phase, as the Norse

and their superior sea power annexed the island half

of Argyll, that the bonding of these mainland

groups into a permanent and internally complex

state occurred.

Despite historical uncertainty about the relative

power of the Scots and Picts at this time, the Scots

moved eastward, and from about

A.D. 843 Cinead

mac Ailpín (Kenneth mac Alpin) and his descen-

dants ruled both Scots and Picts from Forteviot in

southern Pictland. Later historical revision makes it

difficult to determine to what extent this was a vio-

lent overthrow of Pictish power as opposed to as-

similation. Nonetheless by c.

A.D. 900 Dál Riata and

Pictavia vanish from the sources, replaced by Alba:

a nation called by a Gaelic name and using the Gael-

ic language but with much of its administrative

structure apparently derived from the Picts.

See also Hillforts (vol. 2, part 6); Dál Riata (vol. 2, part

7); Picts (vol. 2, part 7); Viking Settlements in

Orkney and Shetland (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alcock, Leslie, and Elizabeth A. Alcock. “Reconnaissance

Excavations on Early Historic Fortifications and Other

Royal Sites in Scotland, 1974–84: 4, Excavations at Alt

Clut, Clyde Rock, Strathclyde, 1974–75.” Proceedings

of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 120 (1990): 95–

149.

———. “Reconnaissance Excavations on Early Historic For-

tifications and Other Royal Sites in Scotland, 1974–84:

2, Excavations at Dunollie Castle, Oban, Argyll, 1978.”

Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 117

(1987): 73–101.

Alcock, Leslie, Elizabeth A. Alcock, and Stephen T. Driscoll.

“Reconnaissance Excavations on Early Historic Fortifi-

cations and Other Royal Sites in Scotland, 1974–84: 3,

Excavations at Dundurn, Strathearn, Perthshire, 1976–

77.” Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland

119 (1989): 189–226.

Clancy, Thomas Owen, and Barbara E. Crawford. “The For-

mation of the Scottish Kingdom.” In The New Penguin

History of Scotland: From the Earliest Times to the Pres-

ent Day. Edited by R. A. Houston and W. W. J. Knox,

pp. 28–95. London: Allen Lane–Penguin Press, 2001.

Crawford, Barbara E. Scandinavian Scotland. Leicester,

U.K.: Leicester University Press, 1987.

Driscoll, Stephen T. “The Archaeology of State Formation

in Scotland.” In Scottish Archaeology: New Perceptions.

Edited by W. S. Hanson and E. A. Slater, pp. 81–111.

Aberdeen, Scotland: Aberdeen University Press, 1991.

Fisher, Ian. Early Medieval Sculpture in the West Highlands

and Islands. Edinburgh: Royal Commission on the An-

cient and Historical Monuments of Scotland–Society of

Antiquaries of Scotland, 2001.

DARK AGE/EARLY MEDIEVAL SCOTLAND

ANCIENT EUROPE

475

Foster, Sally M. Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scot-

land. London: B. T. Batsford–Historic Scotland, 1996.

Graham-Campbell, James, and Colleen E. Batey. Vikings in

Scotland: An Archaeological Survey. Edinburgh: Edin-

burgh University Press, 1998.

Henry, David, ed. The Worm, the Germ, and the Thorn: Pict-

ish and Related Studies Presented to Isabel Henderson.

Balgavies, U.K.: Pinkfoot Press, 1997.

Hill, Peter. Whithorn and St. Ninian: The Excavation of a

Monastic Town 1984–91. Stroud, U.K.: Alan Sutton

Publishing–Whithorn Trust, 1997.

Laing, Lloyd, and Jenny Laing. The Picts and the Scots.

Stroud, U.K.: Alan Sutton Publishing, 1993.

Lane, Alan, and Ewan Campbell. Dunadd: An Early Dal-

riadic Capital. Oxford: Oxbow Books, 2000.

Ritchie, Anna. Viking Scotland. London: B. T. Batsford–

Historic Scotland, 1993.

Spearman, R. Michael, and John Higgitt, eds. The Age of Mi-

grating Ideas: Early Medieval Art in Northern Britain

and Ireland. Stroud, U.K.: Alan Sutton Publishing;

Edinburgh: National Museums of Scotland, 1993.

Wainwright, F. T. The Problem of the Picts. Edinburgh:

Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1955.

E

LIZABETH A. RAGAN

■

TARBAT

The Gaelic word tarbat refers to a dry crossing

where boats were hauled across the neck of a penin-

sula. The Tarbat peninsula in northeastern Scotland

juts into the Moray Firth and permitted such cross-

ings between Cromarty and Dornoch Firths. This

peninsula contains some of the finest sculpture of

the European Early Middle Ages. It is now recog-

nized as the site of the first and so far the only

known early monastery in eastern Scotland, land of

the lost nation of the Picts.

The sculpture at Tarbat survives in the form of

monumental cross slabs, all carved and erected

about

A.D. 800. At Nigg, at the southern foot of the

peninsula, the cross-slab features the biblical king

David and the story of St. Paul and St. Anthony in

the desert. At Shandwick, the large cross is accom-

panied by cherubim and seraphim and a mass of in-

tricate Celtic spiral ornament. At Hilton of Cadboll,

the cross side of the slab has been erased, but the re-

verse features a secular scene showing a woman rid-

ing to the hunt accompanied by servants and hunts-

men. All of these cross slabs face the sea, and all

carry symbols of the Pictish iconic language, sym-

bols that probably represent the names of the per-

sons commemorated.

Archaeological excavation since 1994 at the

peninsula’s main settlement of Portmahomack has

given a context for these remarkable monuments

(fig. 1). During the nineteenth century, pieces of

carved stone were discovered by gravediggers in the

churchyard and surroundings of Portmahomack’s

church of St. Colman. Among them was a stone

carved in relief in insular majuscules recalling the

Book of Kells (approximately

A.D. 800). In 1984 a

buried ditch around the church was discovered by

aerial survey. The ditch’s D-shaped plan recalled the

enclosure that defines the monastery of St. Colum-

ba (Columcille) on Iona, an island off western Scot-

land. It was Columba (according to Adomnán of

Iona, his biographer) who had attempted to convert

the northern Picts around

A.D. 565. Here were clues

that Portmahomack might have been a settlement

of the first Christians in Pictland.

In 1994 the University of York was invited by

a local restoration group (Tarbat Historic Trust) to

adopt the site as a research project. After an initial

evaluation, the church itself was excavated and its

fabric recorded, while outside the churchyard an

area of 0.6 hectare was opened, with sensational re-

sults. In the church, excavators recorded a sequence

of two hundred burials, beginning with sixty-seven

graves that were wholly or partly lined with stone

slabs (the distinctive “cist” burials of the Picts).

These proved to contain the remains of primarily

middle-aged or elderly men, the earliest of which

has been radiocarbon dated to the sixth century

A.D.

The later burials, with a more normal distribution

of men, women, and children, belong to the twelfth

to fifteenth centuries

A.D. Six principal phases of

church building were distinguished. The earliest

stone church is signaled by a single wall and proba-

bly dates to the eighth century

A.D. It was replaced

in the twelfth century by an east-west chapel with

a square-ended chancel, which was lengthened and

provided with a tower and crypt in the thirteenth

century. In the sixteenth century (at the Reforma-

tion) the axis of worship was altered to run north-

south and a northern “aisle,” or quarter, reserved

for the laird, was constructed. When the Church of

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

476

ANCIENT EUROPE

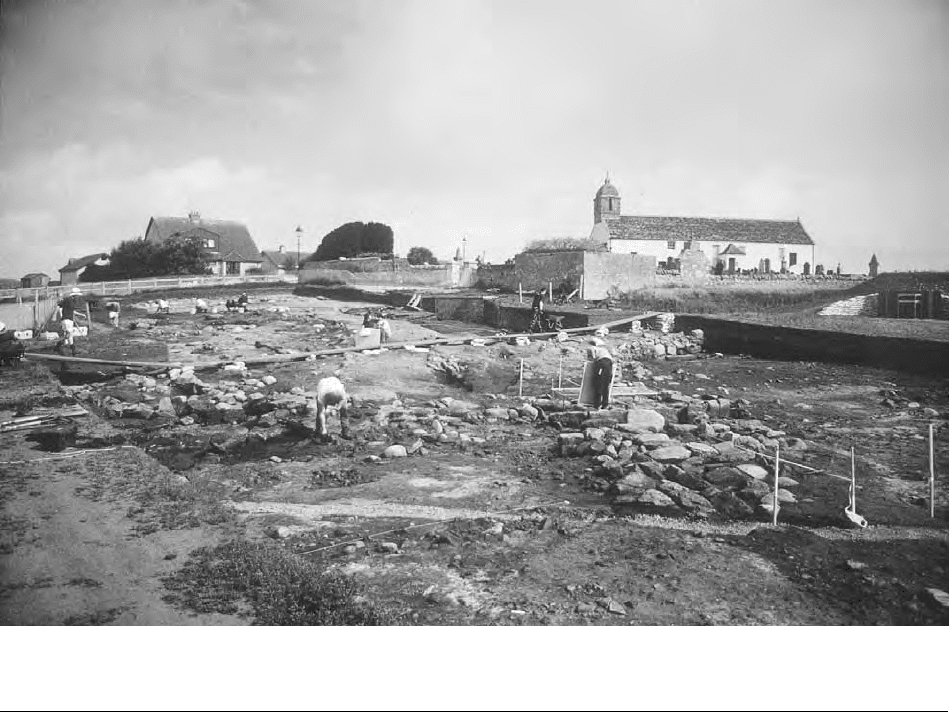

Fig. 1. Excavations at Portmahomack in 2000. In the background is the church of St. Colman; to the left workshops are under

excavation; and in the foreground is the dam for the mill pond. © MARTIN CARVER AND THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK. REPRODUCED BY

PERMISSION

.

Scotland split in two because of the Disruption of

1843, the axis returned to the east-west. The con-

struction of the present church largely dates from a

restoration undertaken in the mid-eighteenth cen-

tury.

Numerous pieces of carved stone were found to

have been reused in the foundations of the elev-

enth-century church, the majority carrying orna-

ment of the eighth century. As of the early 2000s,

more than 150 carved stones had been recovered

from excavation in the church or outside it. Many

of these are simple grave-markers carrying a cross

and recalling examples known from Iona. One mas-

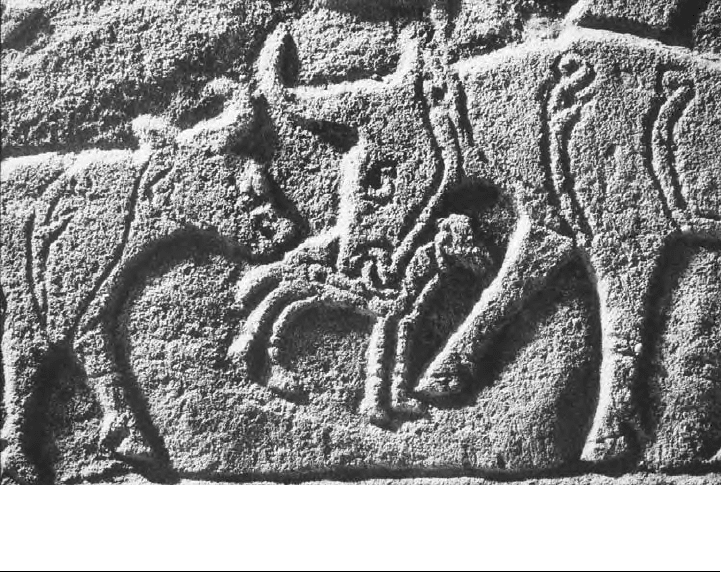

sive slab with a lion and a wild boar in relief belongs

to a sarcophagus lid, or possibly an altar. Another

with a picture of a family of cattle comes from a wall

slab, perhaps a cancellum (fig. 2). Many other pieces

derive from one or more monumental cross slabs

that closely resemble those surviving at Nigg and

Shandwick.

Excavations in the field next to the church re-

vealed a large segment of an early Christian monas-

tery in plan. Nearest to the church is a workshop

area laid out on either side of a paved road. The

workshops have produced evidence for the making

of objects of silver (cuppelation dishes), bronze

(hearths, crucibles, molds, and whetstones), glass

(molds), leather (a tanning pit, bone pegs for a

stretcher frame, and pumice leather-smoothers),

and wood (a chisel clad by ferriferous wood shav-

ings). The objects that were made appear to have

been ecclesiastical in nature, since the molds and

studs recall reliquaries and liturgical vessels known

from the early Celtic world. South of the workshops

is a millpond with a dam to provide a head of water

for driving a horizontal millwheel. Farther south,

still against the enclosure boundary, lie a number of

grain-drying pits and the foundations of a timber-

framed structure bag-shaped in plan. This was prob-

ably a kiln-barn, although its hearth shows evidence

TARBAT

ANCIENT EUROPE

477

Fig. 2. A family of cattle carved on a slab found at Portmahomack, Easter Ross, eighth century

A.D. After the monastery was destroyed by the Vikings, the slab was reused as a drain cover.

© MARTIN CARVER AND THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

of use by a blacksmith. The boundary ditch itself

was by no means defensive but appears to have been

employed in collecting and bringing water to differ-

ent areas of the monastery.

The male burials, the sculpture, the inscription,

the enclosure, and the manufacture of ecclesiastical

objects identify the Portmahomack settlement as an

early monastery. The earliest burial took place in the

sixth century, while the majority of the artifacts, in-

cluding the sculpture, belong to the eighth century

with a terminus around 800. Records indicate that

Columba settled in Iona in 563 and took part in an

expedition to the northern Picts in 565. He passed

up the Great Glen by way of Loch Ness and met the

Pictish king Bridei, son of Mailchu, somewhere near

Inverness. Although the conversion of the Picts is

not claimed in Adomnán’s Life of St. Columba, he

does say that monasteries were founded in Colum-

ba’s time. Discoveries from the 1990s allow us to

identify Portmahomack (“port of Colman”—or

Columba) as one of these, established at the oppo-

site end of the Great Glen to Iona, perhaps by Co-

lumba himself. By

A.D. 800 the whole Tarbat penin-

sula had emerged as a major ecclesiastical center, its

boundaries marked by monumental cross slabs car-

rying some of the most complex iconography seen

in early Christian art. The end of the monastery and

its consignment to oblivion for more than one

thousand years remain something of a mystery.

Sometime between 800 and 1100, the workshop

area was destroyed by fire, and at the same time the

monumental cross slabs were broken up and

dumped. It seems likely that this targeted attack was

the work of the Vikings.

See also Celts (vol. 2, part 6); Picts (vol. 2, part 7);

Vikings (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adomnán of Iona. Life of St Columba. Translated by Richard

Sharpe. Harmondsworth, U.K., and New York: Pen-

guin, 1991.

Bulletins of the Tarbat Discovery Programme. 1995–. Avail-

able at www.york.ac.uk/depts/arch/staff/sites/tarbat.

Carver, Martin. Surviving in Symbols: A Visit to the Pictish

Nation. Edinburgh: Canongate, 1999.

———. “Conversion and Politics on the Eastern Seaboard

of Britain: Some Achaeological Indicators.” In Conver-

sion and Christianity in the North Sea World. Edited by

Barbara E. Crawford, pp. 11–40. St. Andrews, U.K.:

University of St. Andrews, 1998.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

478

ANCIENT EUROPE

Foster, Sally. Picts, Gaels, and Scots. London: B. T. Batsford/

Historic Scotland, 1996.

M

ARTIN CARVER

TARBAT

ANCIENT EUROPE

479

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

EARLY MEDIEVAL WALES

■

The archaeology of early medieval Wales has been

studied largely within a historical framework pri-

marily derived from sources created late in the peri-

od under consideration, about

A.D. 400 to 1000,

with many of the written sources even later than this

and their relevance to earlier periods inferred. Two

major themes have emerged from research, that of

elite settlements and ecclesiastical archaeology. Elite

settlements were first defined at Dinas Powys, Gla-

morganshire, with the presence of imported vessels

and craft production debris. Subsequent excava-

tions have widened the range of such site types, but

they have done little to reveal later high-status sites

or much of the lower-level settlements of any part

of the period. Ecclesiastical archaeology has relied

heavily on sculpture and inscriptions but has been

augmented by important excavated evidence of

burial. Research has also increased the evidence for

Viking settlement, and there is lively debate regard-

ing the interpretation of the inscribed stones and

sculpture.

POST-ROMAN CONTINUITY

Some late Roman military activity is known at sites

such as Cardiff, various locations on Anglesey, and

at Caernarfon. These are thought to have been a re-

action to Irish raids that led to Irish settlement in

several parts of Wales. Even after the Roman mili-

tary presence ceased around

A.D. 410, aspects of

Roman life continued into the fifth and sixth centu-

ries, though settlement evidence for this is inconclu-

sive and relies more on later inscriptions discussed

below.

Several high-status Romanized sites in south-

eastern Wales show reuse. At villas such as Llantwit

Major there may have been continuity of estates

that later came within a monastic context. Other re-

ligious foundations were created at Roman sites

such as Caer Gybi, Anglesey, in northwestern Wales

and Caerwent, Gwent, in southeastern Wales,

though in these cases there may have been a consid-

erable hiatus between Roman abandonment and

early medieval use. In some cases such as Cold

Knap, Glamorganshire, the occupation seems secu-

lar, and was set in the ruins of the Roman structures.

Here, again, a gap in occupation is suggested. Some

continuity of settlement is demonstrated at a few

burial locations discussed below, suggesting that es-

tates and communities may have continued, even if

the location and nature of settlement sites on those

estates altered following the end of the Roman

period.

Hillforts in Wales have produced evidence of

late Roman occupation, and a few have activity from

the early medieval period also, although continuity

of settlement or repeated episodes of reuse are both

possible. Several native settlements such as

Graeanog, Gwynedd, and some of the enclosed

farmsteads around Llawhaden, Pembrokeshire, sug-

gest that such sites continued to attract habitation

into the fifth and sixth centuries.

The most obvious archaeological evidence for

continuity of Roman traditions and elements of cul-

ture comes from some of the inscribed stones.

Though difficult to date, some from the fifth and

480

ANCIENT EUROPE