Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

farm’s animals, a storage place for grain, and work-

shops for common crafts, such as ironworking. Ex-

cavations of higher-status ringforts often reveal a

greater range of crafts produced, including the

manufacture of objects made of bronze and pre-

cious metals. However, the essential function of

high- and low-status ringforts varied little.

The actual defensive capabilities of ringforts is

debated, with some archaeologists viewing the walls

simply as a way to keep animals in the farmyard and

having no defensive use, while others have argued

for palisaded or hedge-lined embankments with

some sort of defensive character. The most defen-

sive element of ringforts, however, was perhaps not

in their physical layout but in their distribution

across the countryside. Studies have shown that

ringforts regularly occur in semiclustered groups.

Although quite separated in distance, each ringfort

would have been within sight of another, and these

clusters often have a larger and presumably more

defensive multivallate ringfort within close proximi-

ty. This would have created an interlocking commu-

nity that used the view across the landscape as a type

of defense and that would have given the inhabi-

tants time to flee to more defensive positions in the

larger ringforts or in the surrounding mountains

and bog lands.

Crannogs are artificial islands built in lakes and

rivers that are located primarily in the northern and

western parts of Ireland. While not as numerous as

ringforts (about two thousand Irish crannogs have

been identified), these sites are the second most

common type of early medieval settlement and have

played a central role in understanding the period.

They are considered a predominantly early medieval

class of settlement, although research in the 2000s

has extended the chronology of crannog construc-

tion back into the Late Bronze Age and perhaps ear-

lier. The nature of crannog use may have been much

different prior to c.

A.D. 400, with crannogs perhaps

serving a predominantly ritual use in earlier periods

or as seasonal dwellings only. Evidence for their use

in the Iron Age (c. 700

B.C.–A.D. 400) is very scarce,

and it is during the early medieval period that cran-

nogs developed as settlements. Most crannogs are

built up on lake and river beds with stones and de-

bris until they emerge from the water, and some

have stone causeways built connecting the crannog

to the shore. These artificial islands were then sur-

rounded with wooden palisades, and houses and

other outbuildings were located inside. Crannogs

vary greatly in size and shape but are most common-

ly oval or round in plan and about 20 meters in di-

ameter.

Unlike ringforts, crannogs were probably not

directly related to the farming economy, as their lo-

cation in the water would make access to fields and

animals quite difficult. However, large amounts of

animal bones are often found on excavated cran-

nogs, and this is commonly interpreted as evidence

of feasting by the occupants. This supports the be-

lief that crannogs were the bases of powerful lords,

and some crannogs have been identified by histori-

cal documents as royal centers. Excavations of these

high-status and royal crannogs have revealed exten-

sive evidence of metalworking, the large-scale man-

ufacture of brooches and other high-status personal

objects, and impressive collections of imported

goods, such as Continental and Mediterranean pot-

tery. Despite the large amounts of archaeological

material commonly found on crannogs, most seem

to have no more than one or two small houses and

were probably inhabited by a family group. Excava-

tions have traditionally focused on these higher-

status sites, but research since the late 1990s has re-

vealed that there are also less-wealthy crannogs.

Their role in the early medieval settlement pattern

is, however, less well understood.

See also Celts (vol. 2, part 6); Early Christian Ireland

(vol. 2, part 7); Dark Age/Early Medieval Scotland

(vol. 2, part 7); Early Medieval Wales (vol. 2, part

7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Edwards, Nancy. The Archaeology of Early Medieval Ireland.

London: Routledge, 1990.

Fredengren, Christina. Crannogs: A Study of People’s Inter-

action with Lakes, with Particular Reference to Lough

Gara in the North-west of Ireland. Bray, Ireland: Word-

well, 2002.

O’Sullivan, Aidan. The Archaeology of Lake Settlement in Ire-

land. Discovery Programme Monograph, no. 4. Dub-

lin: Royal Irish Academy, 1998.

Stout, Matthew. The Irish Ringfort. Dublin: Four Courts

Press, 1997.

J

AMES W. BOYLE

RATHS, CRANNOGS, AND CASHELS

ANCIENT EUROPE

461

■

DEER PARK FARMS

Late in 1984 a rath mound in Deer Park Farms

townland in Glenarm, County Antrim, was threat-

ened with destruction in the course of farm im-

provements. It proved impossible to preserve the

monument by negotiation, so four summer seasons

of rescue excavations were carried out by the De-

partment of the Environment (Northern Ireland).

These revealed a remarkable sequence of well-

preserved houses and associated finds. The rath

stood at a height of 150 meters above sea level in

a north-sloping field overlooking the Glenarm

River. The monument was a large flat-topped

mound, 26 meters in diameter across the summit

and 4.5 meters high. The base of the mound was

about 50 meters in diameter and was encircled by

a ditch, very wide and deep on the uphill side. Oc-

cupation layers were visible at various heights in the

mound’s sides, showing that it had built up in stages

over a period of time.

The surface on which the rath was built revealed

several prehistoric features, probably dating from

the Bronze Age or earlier. The first feature of the

early Christian period was a circular ring ditch, with

an overall diameter of 25 meters and an east-facing

entrance gap. The ditch was about 2 meters wide

and 1 meter deep. It was not accompanied by a bank

and may have served to delimit and help drain the

site chosen for settlement in the early Christian peri-

od, probably in the mid-seventh century. The ditch

had silted up or had been deliberately filled in be-

fore the rath was built over it.

Before the end of the seventh century the first

rath bank was constructed approximately over the

site of the primary ring ditch. The external ditch

that went with the bank was cut away by subsequent

enlargement to obtain material for heightening the

rath. Probably at the same time as the first rath bank

was built, the first of a long sequence of woven hazel

buildings was erected in the enclosure.

After a lengthy period of occupation, perhaps

fifty years, the rath was converted into a flat-topped

mound and a sloping access ramp of clay and gravel

was built over the original east-facing entrance. The

outer surface of the mound was encased in a heavy

revetment wall of basalt boulders and the ditch was

deepened. This main phase of mound heightening

was accomplished in several stages. The houses in

the final stage of the rath were not abandoned and

replaced all at once, as had been presumed on the

basis of trial excavations at other rath mounds. In-

stead, each house was abandoned and its remains

covered over only when it reached the end of its use-

ful life. As a result, some new houses stood on iso-

lated platforms overlooking other inhabited houses

not yet replaced. Two souterrains were incorporat-

ed in a further heightening of the rath, probably by

the end of the tenth century.

The hillside site sloped to the north, but the

rath entrance faced east, with the result that there

was persistent ponding of water against the inner

face of the clay bank on the downslope, north side.

This resulted in the preservation of an accumulation

of organic midden material in this area up to 1.5

meters deep. The heightening of the rath caused a

rise in the water table in the mound, which pre-

served the wickerwork remains of the buried houses

in the final phase of the primary, unheightened rath.

This well-preserved horizon, dating from the early

eighth century, is characteristic of the occupation

surfaces of the entire rath.

The most obvious feature of the rath in the early

eighth century is, paradoxically, untypical. The en-

trance, instead of being a simple gap, was inturned.

Two parallel banks of earth ran for 6.5 meters into

the rath interior. They were stone-revetted on the

inner faces and formed a long, stone-paved rectan-

gular antechamber inside the gate some 11 meters

by 3.8 meters. A further meter inward from the end

of the antechamber was the doorway of the largest

house, which stood at the center of the rath. This

was of figure-eight plan and the larger component,

the main house, was 7.4 meters in diameter. It had

a central, stone-curbed, rectangular fireplace, also

aligned on the easterly axis of the rath layout. The

structure, like all the others found in the rath, was

double-walled. The inner wall bore the main weight

of the structure, whereas the outer wall, spaced 30

centimeters away, mainly served to retain insulating

material—grass, straw, weeds and bracken—in place

against the inner wall. The smaller “backhouse,”

which could be entered only from within the main

dwelling, was 5 meters in diameter. Its woven walls

interlocked with those of the main house showing

that the two elements of this figure-eight-shaped

house had been built simultaneously. This figure-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

462

ANCIENT EUROPE

Fig. 1. Wickerwork structures zeta (left) and X (right), early eighth century. The structures were woven together as a conjoined

figure-of-eight unit with zeta as the backhouse, which could be entered only from X. The communicating gap was closed by a

woven hurdle as zeta was abandoned before X. To the left, in zeta, is a collapsed section of its inner wall, almost reaching the

central fireplace. At the bottom right are branches forming the base of a bedding area in the south side of structure X. This

composite structure at the center of the rath was clearly the most important in this phase, with smaller dwellings set behind to

north and south. © CROWN COPYRIGHT. COURTESY OF CHRIS LYNN, ENVIRONMENT AND HERITAGE SERVICE. REPRODUCED WITH THE PERMISSION OF

THE

CONTROLLER OF HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE.

eight plan was the normal layout for the main dwell-

ing at the center of the rath in other phases.

The walls were woven using a basketry tech-

nique, giving an enormously strong structure. The

horizontal component of the wall was woven in spi-

raling sets of 2-meter-long hazel rods twisted

around short uprights, giving the courses of the wall

a spiralling rope-like appearance. The surfaces of

both inner and outer walls were smooth, because

the cut ends of the hazel rods were hidden in the

space between the walls. The uprights of the wall

were composite: they did not run continuously

through the full height of the structure. The first set

of pointed uprights was driven into the ground

about 25 centimeters apart and rose to a height of

about 1 meter. When wall weaving reached this

height, the next set of uprights was hammered into

the body of the woven wall alongside the primary

uprights. These protruded up for a further meter,

wall weaving continued to that height, a further set

of uprights was hammered in, and so on. In one area

a large panel of pushed-over walling was found,

which would have stood to nearly 4 meters in

height, showing that the roof was probably con-

structed in a similar technique to the walls and not

as a separate cone of long rafters.

The central house had two bedding areas, one

on the north and one on the south, formed of thin

branches and twigs alternately laid radially and con-

centrically against the house walls. These were filled

with finer chopped vegetable material. The ends of

the bed on the north were protected by wicker

screens fixed into drilled holes in oak beams on the

floor, forming bed ends. Two stone-curbed paths

DEER PARK FARMS

ANCIENT EUROPE

463

ran north and south on either side of the entrance

to the main house and curved to the west to provide

formal access to two other dwellings. The one on

the south was a simple single circular house or hut

with a central fireplace and a bedding area on the

north. The structure on the north was another fig-

ure-eight, but smaller than the central one. The

western component of this structure at first stood as

an isolated single house, but after some time the

larger, eastern component was woven onto the

front of it. This may reflect a change in the social

status of the occupant of the single home, for exam-

ple maturity and marriage. The complete doorframe

of the primary component of the figure-eight was

preserved. This was the outside doorframe of the

original single house, which then became the con-

necting door between the conjoined houses. The

isolated house on the south may have been occu-

pied by a single or widowed relative of the occupant

of the main central house.

One of the most interesting aspects of the exca-

vation is the close correlation between the archaeo-

logical evidence from the site and the details of

houses, furniture, fittings, and personal equipment

and tools given in the contemporary law tracts on

status. These specify the equipment and buildings

appropriate to hierarchial grades of free farmers who

lived in raths. Hitherto, these legal inventories have

been considered by archaeologists as somewhat ide-

alized and not a true representation of reality. The

occupants of the rath at this phase possessed many

artifacts and craft-techniques listed in the law tracts

as appropriate to what would now be termed upper-

middle-class farmers. They used a coppicing meth-

od to grow hazel for their houses and fences, they

wore composite leather shoes, they ate a variety of

animal products (cow, sheep, pig), and they had ac-

cess to a water mill for grinding cereals. The wood-

en hub and two paddles of a mill wheel were found

in the waterlogged midden. The rath occupants

wore woolen clothes; they plowed the land (as evi-

denced by two iron plough tips); they made their

own stave-built wooden vessels, probably using

light from iron candle and rush-light holders also

found in the excavation. They had metal cooking

pots and hooks for hanging meat, they cultivated

woad for dyeing, and they decorated themselves

from an extensive range of metal pins and colored

glass beads. More personally, evidence suggests that

they and their settlement were occupied by more

than sixty species of parasitic and decomposer insect

species, in proportions normally regarded as typical

of more densely occupied urban sites, such as Vi-

king Age York. From the number of head-louse re-

mains found immediately outside the main central

structure, one can picture the family sitting on the

end wall of the entranceway combing and grooming

one another. Perhaps hair cutting went on at the

same time as five locks of cut human hair were

found in different levels of the midden nearby.

The deposits in the lower levels of the Deer Park

Farms rath were uniquely well preserved, permitting

close contact with the life of the people who lived

there. In the context of this encyclopedia one is

tempted to ask, were these people “barbarians”?

What share of their material, cultural inheritance

came from a prehistoric insular past and what had

been adopted from the Roman world? The round

wickerwork houses have not been found in earlier

contexts in Ireland, but little is known about houses

and settlement in Ireland in the preceding Iron Age.

Bronze Age houses, although also of round form,

seem to have been made of heavier materials such

as stone, clay, and timber. Nevertheless, the round

house was essentially a prehistoric form which,

uniquely in Europe, survived in Ireland into the his-

toric period. Circular earthworks are known from

prehistory but these generally occur in ceremonial

or funerary contexts. In turn, this suggests that if

there is some continuity with prehistory, the rath

enclosures may have had a sacred or legal signifi-

cance, identifying the special importance of the

home place. This could include its significance as

the primary domain of women, where household

and lighter agricultural crafts were carried out.

Some of the smaller items of equipment found

in Deer Park Farms and other raths, such as brooch-

es and iron tools, are of forms that can be paralleled

earlier in Roman Britain. Similarly, small enclosed

settlements were built in western Britain during the

Iron Age and Roman period and some researchers

interpret these as being ancestral to Irish raths. The

clear view from Deer Park Farms of Slemish, 8 kilo-

meters to the southwest, suggests that the occu-

pants of the rath adhered to the Christian faith of

the late Roman Empire, introduced to Ireland by

St. Patrick and his contemporaries in the fifth centu-

ry. Slemish is the prominent hill where St. Patrick

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

464

ANCIENT EUROPE

is said to have labored as a swineherd some 250

years before the Deer Park Farms rath was built. A

small hone, found in the midden layer of the rath,

had engraved on it an animal head in the style of the

well-known Tara Brooch (from Bettystown, Coun-

ty Meath). Underneath the head is a scratched in-

scription of seven letters, the earliest archaeological

evidence for an awareness of writing in a domestic

site in Ireland.

See also Early Christian Ireland (vol. 2, part 7); Raths,

Crannogs, and Cashels (vol. 2, part 7); Viking York

(vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Kelly, Fergus. Early Irish Farming. Early Irish Law Series,

no. 4. Dublin: School of Celtic Studies, Dublin Insti-

tute for Advanced Studies, 1997.

Lynn, Chris J., and Jacki A. McDowell. A monograph report

by Lynn and McDowell on the Deer Park Farms excava-

tion is at an advanced stage of preparation. Some draft

chapters may be consulted on the Internet at http://

www.ehsni.gov.uk/built/monuments.

Mytum, Harold. The Origins of Early Christian Ireland.

London: Routledge, 1992.

Stout, Matthew. The Irish Ringfort. Dublin: Four Courts

Press, 1997.

C.

J. LYNN

DEER PARK FARMS

ANCIENT EUROPE

465

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

VIKING DUBLIN

■

Forty years of archaeological excavation in Dublin,

much of it under the aegis of the National Museum

of Ireland, has shed considerable light on the char-

acter of this the largest of the Scandinavian-founded

urban settlements in the west. Although unconcert-

ed as elements of an overall program and begun in

response to building development, in their sum

these excavations add up to the most extensive of

their time and type undertaken in Europe north of

the Alps and west of the Oder. The scale of the total

excavated areas together with the waterlogged air-

less conditions in which as much as 3 meters deep

of organic cultural deposits survive means that there

is excellent evidence for buildings, town layout, de-

fenses, environment, diet, trade, commerce, and ev-

eryday life especially for the three centuries

A.D.

850–1150. There are also well-preserved wooden

dockside revetments and building and carpentry ev-

idence from the thirteenth to the sixteenth centu-

ries.

Ireland is blessed with rich historical sources in-

cluding references to the establishment of Dublin in

about 840, but it was not until the 1960s at sites like

High Street, Winetavern Street, and especially

Christchurch Place, all of which were excavated by

A. B. ó Ríordáin, that the quality of Dublin’s

uniquely rich archaeological deposits became appar-

ent. More extensive work by Patrick Wallace on the

large Fishamble Street–Wood Quay site from 1962

to 1976 expanded on ó Ríordáin’s work, particular-

ly in regard to layout, the succession of town plots

and their boundaries, building evidence, and the

town’s Viking Age port. Work by Clare Walsh at

Ross Road in 1993 gave additional information on

the circuit of the earthen defenses that enclosed the

early town; the Castle Street and Werburgh Street

sites showed that while it was possible to generalize

about buildings and town layout, there are varia-

tions within the town; and Parliament Street and es-

pecially Linzi Simpson’s work at Essex Street

showed that the earliest settlement in the ninth cen-

tury must have been at the confluence of the tidal

Liffey and its southern tributary, the Poddle. It also

showed that the settlement probably expanded

southward up the hill from the waterfront and,

later, that the early medieval town expanded from

east to west. Most significantly, work done from

1996 to 1998 indicates that the main building type,

with its tripartite floor space arranged longitudinally

between doors in the end walls, was established al-

most from the beginning and persisted throughout

the period up to the twelfth century and possibly

beyond (going by the evidence from the parallel

Hiberno-Norse town of Wexford) and that the set-

tlement was divided into plots or yards well before

900.

Although Ireland’s great monastic “towns”

flourished from before the arrival of the Vikings

and, with other native settlements of this culturally

extraordinary phase of Ireland’s history, had some

urban traits, it is likely that the concept of main-

stream urbanism was introduced to Ireland possibly

from ninth-century England, with the Scandina-

vians acting as the catalysts who transferred the idea.

Excavations at the other Hiberno-Norse towns—

Limerick, Waterford, and Wexford—show that they

466

ANCIENT EUROPE

share many physical traits with Dublin and that it is

now possible to speak of the Hiberno-Norse town

as a phenomenon in archaeology as well as in histo-

ry. Revisits to the historical sources as well as excava-

tions at Cork in 2002 and the great monastery at

Clonmacnoise in the 1990s show that by the late

eleventh–early twelfth century the concept of true

urbanism was fully a part of the overall Irish experi-

ence.

In its developed form in the later tenth century,

Dublin consisted of a number of streets from which

radiated several lanes including an intramural vari-

ant. The settlement was located around high

ground overlooking the tidal and estuarine Liffey

near its confluence with the Poddle. In the early

tenth century it was defended by a palisaded earthen

embankment that encircled the settlement and ac-

commodated ships along its main riverine side. The

extent of the defenses on the West is at present un-

clear. Inside, the settlement was divided into plots

of roughly rectangular shape by low lines of post-

and-wattle fencing; each plot had its own pathway

leading from a street or lane to the entrance of a

main building that was located with an end toward

the street. At the backs of these main buildings were

lesser smaller buildings. It is presumed that plot

owners controlled access to the plots, with access to

the lesser buildings being difficult: in most cases vis-

itors would have had to walk through the main

buildings, which usually straddled the widths of

their plots. Cattle were not kept in the plots; it ap-

pears that they were not kept in town at all but rath-

er were driven to town in great numbers when it was

time for slaughter, judging from the number of

bones that have been recovered from the excava-

tions.

Specialized crafts including those of nonferrous

metalworking, antler (especially comb) working,

woodcarving, and possibly merchandising appear to

have been concentrated in different parts of the

town. Commerce was regulated, to judge from the

hundreds of lead weights (for weighing silver in a

bullion economy) that have been recovered; these

conform to multiples and fractions of what has been

termed a Dublin ounce of 26.6 grams. Ships’ tim-

bers, unworked amber, lignite, soapstone, and even

walrus ivory testify to the import of bulk commodi-

ties; silks (including head scarves), braids, worsteds,

English brooches, and coins are among finished

products that were imported. Discoveries of runic

inscriptions on discarded red-deer antlers and cattle

bones show a persistence of close Scandinavian in-

fluence two centuries after the initial establishment

of the town as a slaving emporium.

In its settled eleventh-century development,

Dublin became very rich due to its location on the

east of the Irish Sea, then a “Viking lake”: it profited

from provisioning ships, from the hire of its large

mercenary fleet (most notably to the Saxons of the

Godwinson dynasty), and from the export of wool-

ens and of manufactured goods like kite brooches,

ringed pins, strap ends, combs, and possibly orna-

ments carved in the local variety of the international

Ringerike style, which was so distinctive and prolific

that it is now called the “Dublin style.”

See also Viking Ships (vol. 2, part 7); Early Christian

Ireland (vol. 2, part 7); Early Medieval Wales (vol.

2, part 7); Viking York (vol. 2, part 1).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clarke, Howard B. Irish Historic Towns Atlas No.11: Dublin,

Part 1, to 1610. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 2002.

———. “The Bloodied Eagle: The Vikings and the Devel-

opment of Dublin, 841–1014.” Irish Sword 18 (1991):

91–119.

Fanning, Thomas. Viking Age Ringed Pins from Dublin.

Medieval Dublin Excavations 1962–1981, series B, vol.

4. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1994.

Hurley, M. F., and S. J. McCutcheon. Late Viking Age and

Medieval Waterford Excavations 1986–1992. Water-

ford, Ireland: Waterford Corporation, 1997.

Lang, James T. Viking Age Decorated Wood: A Study of Its

Ornament and Style. Medieval Dublin Excavations

1962–1981, series B, vol. 1. Dublin: Royal Irish Acade-

my, 1988.

McGrail, Seán. Medieval Boat and Ship Timbers from Dub-

lin. Medieval Dublin Excavations 1962–1981, series B,

vol. 1. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy, 1993.

O’Rahilly, C. “Medieval Limerick: The Growth of Two

Towns.” In Irish Cities. Edited by Howard B. Clarke,

pp. 163–176. Cork, Ireland: Mercier Press, 1995.

Simpson, Linzi. Director’s Findings: Temple Bar West. Dub-

lin: Margaret Gowen, 2000.

Wallace, Patrick F. “Garrda and Airbeada: The Plot Thick-

ens in Viking Dublin.” In Seanchas: Essays in Early and

Medieval Irish Archaeology, History, and Literature in

Honour of F. J. Byrne. Edited by Alfred P. Smyth. Dub-

lin: Four Courts Press, 2000.

VIKING DUBLIN

ANCIENT EUROPE

467

———. “The Archaeological Identity of the Hiberno-Norse

Town.” Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of

Ireland 122 (1992): 35–66.

———. The Viking Age Buildings of Dublin. Medieval Dub-

lin Excavations 1962–1981, series A, vol. 1, 2 parts.

Dublin: National Museum of Ireland, 1992.

———. “The Economy and Commerce of Viking Age Dub-

lin.” In Untersuchungen zu Handel und Verkehr der

vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Zeit in Mittel- und

Nordeuropa. Vol. 4, Der Handel der Karolinger- und

Wikingerzeit. Edited by K. Düwel et al., pp. 200–245.

Göttingen, Germany: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht,

1987.

———. “The Archaeology of Anglo-Norman Dublin.” In

The Comparative History of Urban Origins in Non-

Roman Europe. Vol. 2. Edited by Howard B. Clarke

and Anngret Simms, pp. 379–410. BAR International

Series, no. 255. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports,

1985.

———. “The Archaeology of Viking Dublin.” In The Com-

parative History of Urban Origins in Non-Roman Eu-

rope. Vol. 1. Edited by Howard B. Clarke and Anngret

Simms, pp. 103–145. BAR International Series, no.

255. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, 1985.

———. “Carpentry in Ireland,

A.D. 900–1300: The Wood

Quay Evidence.” In Woodworking Techniques before

A.D. 1500. Edited by Seán McGrail, pp. 263–299. BAR

International Series, no. 129. Oxford: British Archaeo-

logical Reports, 1982.

P

ATRICK F. WALLACE

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

468

ANCIENT EUROPE

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

DARK AGE/EARLY MEDIEVAL SCOTLAND

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAY ON:

Tarbat . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 476

■

In the later first millennium A.D., Scotland was a

complex and dynamic mosaic of political and cultur-

al traditions, where natives and incomers (immi-

grants) competed for power and influence—a land

of “four nations and five languages,” in the words

of the contemporary Anglian historian the Venera-

ble Bede. The evidence for the various groups con-

tributing to the development of the kingdom of

Scotland is uneven, however, both in terms of his-

torical sources and archaeological research. It is

therefore necessary to consider the broadest possi-

ble range of information to reconstruct the period:

archaeology, history, linguistics and place-name

studies, and art history provide the most significant

evidence.

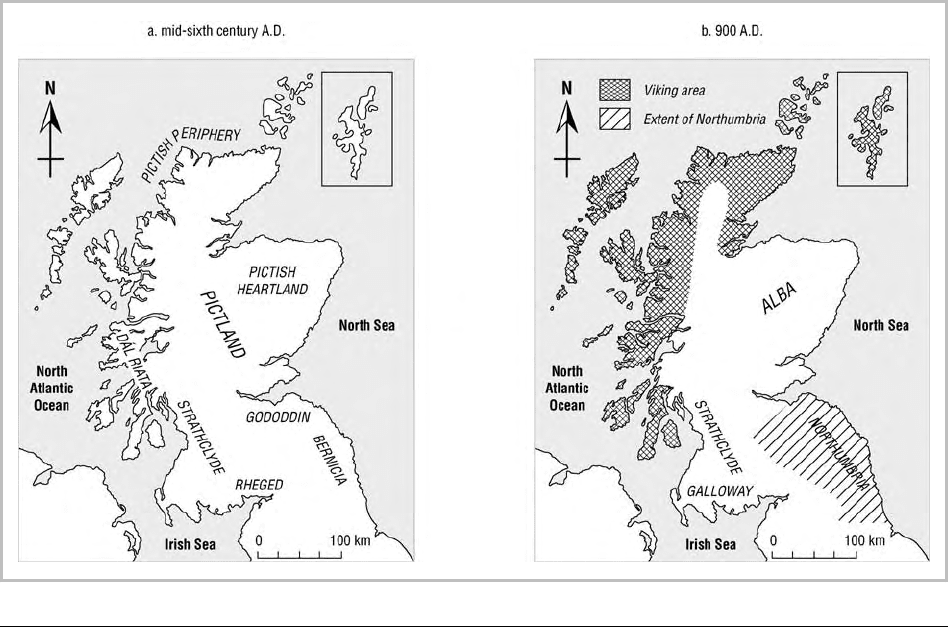

The early medieval period in Scotland can be di-

vided into three major phases. Limited evidence re-

mains for the post-Roman phase (c. fifth century

A.D.), which appears to have been a time of transi-

tion, when significant cultural changes took place.

The early historic or early Christian phase (c. sixth

to eighth centuries

A.D.) was a period of interaction

and competition, at least among the elites, of four

major political or ethnic groups and also saw the es-

tablishment of Christianity as the dominant reli-

gion. Then came the Viking phase (ninth century

through mid–eleventh century

A.D.), when a new

set of pagans, mainly from western Norway, dis-

rupted earlier patterns, initially through raiding and

later by settling in the north and west. Their attacks

were surely an important catalyst for the unification

of the Dalriadic and Pictish kingdoms into Alba, the

kingdom of Scotland.

POST-ROMAN PERIOD

Unlike southern Britain, Scotland never was incor-

porated fully into the Roman Empire, although the

southern lowlands were part of the militarized zone

between the Antonine Wall, which ran between the

River Forth and the River Clyde, and Hadrian’s

Wall, now south of Scotland’s border. Unlike the

situation with the Germanic territories beyond the

Rhine frontier, little evidence suggests significant

levels of trade across these walls, and so the with-

drawal of Rome in the early fifth century was less

obviously disruptive in Scotland than elsewhere. It

is widely accepted, however, that the people be-

tween the walls were influenced significantly by the

Roman military presence. In fact, with the recogni-

tion that the Picts and the Britons both spoke P-

Celtic, or Brittonic languages, some scholars have

suggested that cultural differences between the

southern Britons and the northern Picts may have

been emphasized, if not created, by the adoption of

certain elements of late Roman culture, including

Christianity, by the Britons.

ANCIENT EUROPE

469

Scotland in the mid-sixth century and c. A.D. 900. ADAPTED FROM FOSTER 1996.

Several small kingdoms are known among the

post-Roman Britons. The people the Romans called

the Votadini, for instance, appear in the sixth centu-

ry in the southeast as the Gododdin. In the late

Roman period they were based at the Iron Age hill-

fort of Traprain Law, which has produced a spectac-

ular hoard of Roman silver dated to sometime after

A.D. 395; this cache is interpreted either as loot or,

more likely, a diplomatic bribe or payment for mili-

tary services. But Traprain Law was abandoned by

the mid–fifth century, and it appears that their new

seat of power was at Din Eidyn, modern Edinburgh;

excavations in Edinburgh Castle have found evi-

dence for occupation during this period.

Whithorn, in the southwest, was the site of the

earliest recorded Christian church in Scotland, the

episcopal seat of Saint Ninian, reportedly sent to

minister to an already existing Christian communi-

ty. Dating the activity of any post-Roman figure is

extremely difficult, owing to a lack of contemporary

documents, but scholarly opinion now places Nini-

an at Whithorn in the later fifth century. This dating

is supported by the site’s mid-fifth-century Latinus

stone, an inscribed cross slab with a Latin inscrip-

tion, including the name “Latinus,” and a six-armed

Constantinian Chi-Rho Christian cross.

Little evidence exists for the Picts at this period:

historically they were the enemies of the Romans,

allied with the Scotti (or Irish). Archaeologically

there is strong continuity with Late Iron Age cul-

ture, particularly in the Northern Isles and Western

Isles, although there appear to have been significant

changes in settlement types during the later Roman

period. Understanding of the Picts, however, is

patchy: F. T. Wainwright’s pioneering book titled

The Problem of the Picts was written in 1955, and it

is only since the 1970s that excavations have made

them less of an enigma.

EARLY HISTORIC OR EARLY

CHRISTIAN PERIOD

The Scotti, or at least the Scots of Dál Riata, were

one of two groups that first appeared in Scotland

during the sixth century, complicating the political

picture and contributing new elements to northern

British culture. They controlled Argyll, the south-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

470

ANCIENT EUROPE