Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

MEROVINGIAN FRANCE

■

FOLLOWED BY FEATURE ESSAY ON:

Tomb of Childeric . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 519

■

At the end of the year A.D. 406 a confederation of

Germanic peoples, including Vandals, Suevi, and

Alans, crossed the frozen Rhine near Mainz and

began plundering as far as Spain and North Africa.

The Rhine frontier (limes) was never to be restored,

and the Great Invasions, or Migrations, had reached

Gaul. These movements were set off by the arrival

from central Asia of the Huns in the 370s, thus pro-

voking the panicked Visigoths to break into the

Roman Empire; they were to bring numerous “bar-

barian” peoples into the western provinces to stay

and found new polities. The decisive phase occurred

between the 450s, when the collapse of Hunnic

power and the accelerating fragmentation of Impe-

rial Rome’s authority left the field free for new play-

ers, and the years around 600, when major popula-

tion movements took a hiatus and enduring

territorial identities began to emerge in the west.

By that time the most successful barbarian

dynasty was clearly that of the Merovingian Franks,

reunited under Clotaire II and his son Dagobert in

the early seventh century. The lands between the

Loire and the Rhine, which had been provinces of

Roman Gaul, were becoming known as Francia, the

heartland of this “Frankish” power, which extended

south into more Romanized regions (Aquitania,

Burgundy, and Provence) and eastward into Ger-

manic territories (Thuringia, Alemannia, and Bavar-

ia). What were the roles of the “Franks” and the

“Romans” in the development of this new power

and of the cultural dynamism that was to carry the

Franks to such heights in the oncoming Middle

Ages? These questions have been at the heart of his-

torical debates for centuries and have provided the

framework for the evolution of Merovingian archae-

ology. They spring from the paradigm of the decline

and fall of the Roman Empire, which first took form

under Renaissance historians. When archaeology

began to play a role, this paradigm was conceived in

terms of identifying the historical actors, already

known from the written sources, through studying

their graves.

FUNERARY ARCHAEOLOGY

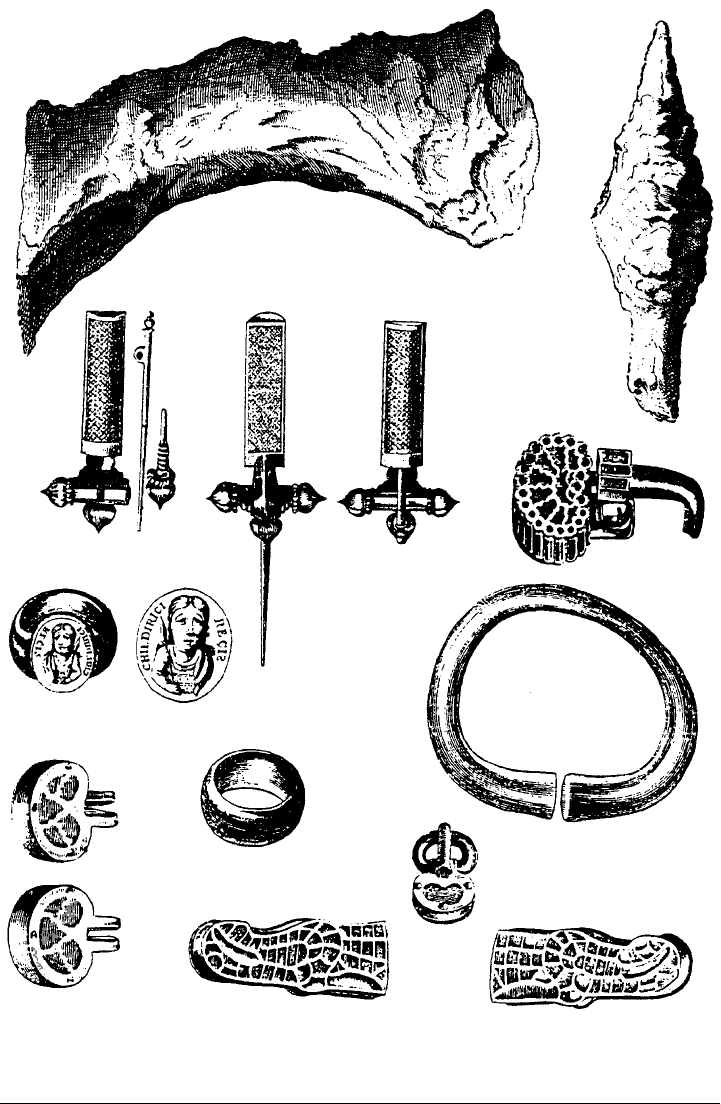

In 1653 during construction near the church of

Saint-Brice in Tournai, Belgium, workers came

upon a “treasure” of gold and silver coins, along

with a profusion of iron and bronze objects—some

clearly weapons—and bones, including two human

skulls and a horse skull. Thanks to the prompt ac-

tion of local authorities and the interest taken by

Archduke Leopold William in asserting ownership,

most of these finds were collected and given for

study to the archduke’s personal physician, Jean-

Jacques Chifflet, who was a noted historian. In

1655 Chifflet published a detailed account of the

ANCIENT EUROPE

511

find, as it could be reconstructed from witnesses and

study of the artifacts, each one carefully illustrated.

Chifflet identified the find as the burial of the

Frankish king Childeric, on the basis of a gold signet

ring that depicted a long-haired warrior holding a

spear and that was inscribed “CILDIRICI REGIS.”

According to the major narrative source for Frank-

ish history, written by Bishop Gregory of Tours (d.

593), Childeric, a ruler of the western Franks, had

fought alongside Roman commanders in the later

fifth century and had died in

A.D. 481/482. His

son, Clovis, then attacked and defeated the Roman

general Syagrius (486), launching a fighting career

during which he eliminated rival Frankish rulers and

defeated other barbarian peoples to establish, by his

death in 511, the first dynasty to rule France, the

Merovingians. The archduke took the Childeric col-

lection with him to Vienna; after his death it was of-

fered to King Louis XIV as a diplomatic present and

disappeared from sight until the nineteenth century.

Over the next two centuries, as graves with arti-

facts turned up in northwest Europe, “antiquaries”

argued over their attribution to specific groups of

ancient peoples known from written sources. After

1800, early industrialization (the construction of

roads and railways) led to the discovery of thou-

sands of graves; this discovery combined with the

growth of scientific methodologies and the Roman-

tic enthusiasm for a national past created a climate

favorable to the emergence of “national archaeolo-

gies.” In 1848 Wilhelm and Ludwig Lindenschmidt

argued convincingly that the twenty-one well-

furnished graves that they had excavated at Selzen

(Rheinhessen) must be Frankish because two of

them included gold coins of the Byzantine emperor

Justinian I (r. 527–565). They published a careful

tomb-by-tomb description with sketches depicting

all the objects in place.

Between 1855 and 1859 the abbé Cochet pub-

lished three influential volumes based on his many

excavations in Normandy. His approach was more

general. He contrasted the indigenous (and pagan)

Gallo-Romans, who typically placed offerings of

food, tableware, and small coins with their cremated

dead, with the invading Germanic warriors, who

laid the unburned bodies in graves, along with

weapons and, for women, ornaments such as

brooches and hairpins. Cochet’s methods were

crude. He usually did not publish tomb drawings or

site plans or grave assemblages, and he did not pay

heed to the chronological dimension of artifacts.

For example, his “typical Frankish warrior” was

shown carrying weapons of different periods and

even female ornaments. Although Cochet rescued

Childeric’s grave from the obscurity into which it

had fallen, he did not appreciate its potential value

as a precisely dated closed-finds assemblage. None-

theless, his enthusiasm for Merovingian archaeolo-

gy stimulated interest in this new discipline in

France and abroad.

In the half-century before World War I thou-

sands of graves were opened, often as the by-

product of construction. What may be called the

“ethnic paradigm” remained dominant. In 1860

Henri Baudot published an account of graves at

Charnay (near Dijon), which he thought must be

those of Burgundians before their kingdom was

conquered by the Franks in 534. In 1892 and 1901

Camille Barrière-Flavy published material from

graves in southwestern France, labeling it “Visi-

gothic” on the principal ground that the Visigoths

had ruled this region until their defeat by Clovis in

507. Some researchers developed notions of field

methodology and the critical problems posed by the

material uncovered. The abbé Haigneré in 1866

published a study of four cemeteries in Boulogne

with a list of artifact assemblages for each grave and,

for one site, a plan with each grave numbered. In

Picardy, Jules Pilloy proposed the first chronologi-

cal study of Merovingian artifacts. He distinguished

an early period that corresponded to the invasions;

a second one marking the growth of Merovingian

power in the sixth century; a later phase of transi-

tion, when weapons such as the throwing axe (fran-

cisca) disappeared from grave groups and a new

type, a single-edged short sword (scramasax), ap-

peared; and a final phase, characterized by such ob-

jects as iron plate buckles with silver and gold inlay

(damasquinure), which he took to be Carolingian

(fig. 1).

While such men as Pilloy and the abbé Haigneré

were laying the foundations for sound research,

other diggers were pillaging sites to sell the booty

on the expanding antiquities market. The example

of Fréderic Moreau illustrates another type of exca-

vator of the day. He worked on a vast scale, opening

thousands of graves. Although he was known to

present artifacts to visitors, he kept a daily excava-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

512

ANCIENT EUROPE

Fig. 1. Belt buckles and plate, Merovingian era, from Dangolsheim tomb. THE ART ARCHIVE/

ARCHAEOLOGICAL MUSEUM STRASBOURG/DAGLI ORTI. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

tion journal, maintained a restoration laboratory in

his house, and privately printed summaries of his

work in folio albums with splendid color litho-

graphs. World War I led to a significant decline in

Merovingian archaeological activity in France, last-

ing into the 1960s. Excavations were few and limit-

ed in scope; the most important general studies

were by foreign scholars, such as the Swede Nils

A

˚

berg and the German Hans Zeiss. Édouard Salin

kept the French tradition alive. A mining engineer

from Lorraine, he began excavating rural cemeteries

in that region in 1912 and continued to dig and

publish through the 1950s. He gave impetus to

technical studies by founding, with Albert France-

Lanord, the first laboratory in France specializing in

archaeological metallurgy, the Musée de l’Histoire

du Fer in Nancy. He proposed an ambitious general

interpretation of the Merovingian period founded

on graves, written sources, and laboratory analysis.

The technical studies of Merovingian metalwork

were highly innovative, demonstrating the complex

skills that went into making pattern-welded swords,

iron belt buckles decorated with patterns of inlaid

gold and silver wire, and gold-and-garnet and gold

filigree brooches.

Salin’s historical vision remained firmly within

the boundaries of the “ethnic paradigm”: He set

out to distinguish Gallo-Roman from Germanic

graves on the basis of typical artifacts and funerary

customs and to identify the particular groups of “in-

vaders”—Franks, Burgundians, Alemanni, and Visi-

goths. These groups were presumed to have come

into contact with one another at the time of the

“Great Invasions” of the fifth century, as distinct

groups with fully formed funerary traditions. At a

particular site, such as Villey-Saint-Etienne in Lor-

raine, the archaeologist could discern how, over

time, these traditions interacted, giving rise to a new

funerary culture in later Merovingian times. Salin

stressed that all aspects of this practice—grave con-

struction and orientation, cemetery organization,

such traces of ritual activity as fire, and body posi-

tion—needed to be considered along with the arti-

fact assemblages. Like the abbé Cochet, Salin was

deeply interested in what could be learned about

ideology and religion from these graves.

Salin’s earlier notion of “progressive fusion”

overlaps here with the idea of “Christianization.”

He assumed that the original funerary culture was

pagan, the antithesis of the Christian funerary cul-

MEROVINGIAN FRANCE

ANCIENT EUROPE

513

ture practiced by the Gallo-Romans, and that the

latter gradually triumphed, leading to the abandon-

ment of the old “row-grave cemeteries” and the dis-

appearance of artifacts from graves during the later

Merovingian period. At the end of his career, Salin

engaged in the excavation of Merovingian sarcoph-

agi in the crypt of the abbey church of Saint-Denis,

associated with King Dagobert (r. 629–639).

During the 1970s and 1980s French archaeolo-

gy became more professional, and Merovingian ar-

chaeology benefited for the first time from leader-

ship based in research organizations. Excavations by

the C.R.A.M. (Center for Medieval Archaeological

Research) in the Caen region soon corrected the

earlier impression that there had been little Mero-

vingian activity in western Normandy; Frénouville

was the first Merovingian cemetery in France to be

totally excavated and published. In the Rhône-Alps

region a group of archaeologists from Geneva,

Lyon, and Grenoble excavated numerous early me-

dieval churches and cemeteries in consultation with

one another. One of them, Michel Colardelle, pub-

lished a global study of funerary archaeology in this

region from the late Roman to the medieval period.

The intellectual center of the Merovingian re-

vival was the A.F.A.M. (Association Française

d’Archéologie Mérovingienne; French Association

of Merovingian Archaeology), founded in 1979 by

Patrick Périn. Périn’s study of a rich early Merovin-

gian cemetery in his hometown of Charleville-

Mézières led him to focus on the refinement of

chronological systems as the key to progress. He de-

veloped an artifact typology based on a series of

cemeteries in the Champagne-Ardennes region,

studied the frequency of object associations and

their changes over time, and proposed a system of

phases tied to absolute chronology by well-dated

reference graves. Périn also stressed the fundamen-

tal importance of using these tools to study the in-

ternal dynamics of each cemetery, or its

“topochronology.”

The decades of the late twentieth century were

marked by higher standards of fieldwork, more

post-excavation specialist studies, and a much more

critical attitude toward the problems of interpreting

fragmentary archaeological data in the light of selec-

tive written sources. The direct link assumed by

Salin between religion and funerary practice has

been criticized, for example. Correlations that were

drawn between funerary culture and ethnic identity

now appear much more complex and ambiguous.

The close and careful work of several archaeologists

has supported the emergence of a “Germanic” fu-

nerary rite within and beyond the Roman frontiers

during the late empire (c.

A.D. 350–450), which

provided the basis for the Frankish funerary rite that

emerged and spread under Childeric and Clovis. A

generation later, this cultural model was established

in newly conquered regions, from Basel in Switzer-

land to Saintes in Aquitania.

Most researchers now agree that the Visigoths

did not have an archaeologically distinct funerary

culture while they occupied Aquitania, nor did the

early Burgundians in eastern France, except, per-

haps, for a few artificially deformed skulls. This is an

unusual example of a plausible ethno-cultural con-

clusion drawn from skeletal data. Other studies have

established that, while much can be learned from

physical anthropology about ancient population

structures, their health, and their relative homoge-

neity, these data do not lend themselves to ethnic

profiling. Funerary practice could, on the other

hand, reflect episodic assertions of group or regional

identity, such as the belt buckles with Christian ico-

nography that flourished briefly in part of Merovin-

gian Burgundy. Researchers have pointed to the

need to allow for the role of ceremony and display,

usually archaeologically invisible, in understanding

funerary practice. For the region around Metz, for

example, the funerary domain might well have been

a site of contest among local elite groups struggling

for hegemony.

SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY

Settlement archaeology is a new and rapidly ex-

panding field in France. As late as 1970 fewer than

twenty sites were known, and none of them were

explored more than partially. Not until 1972 was a

Merovingian village—Brébieres, near Douai—

excavated and the finds published in France. Be-

tween 1980 and 1993, 127 new sites became

known, and the number has continued to rise.

This trend reflects the building boom in those

years, coupled with legally mandated salvage ar-

chaeology, which is carried out with great method-

ological rigor at a pace and on a scale that dwarfs

anything done in the past. For instance, in 1998 a

team that included specialists of the prehistoric,

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

514

ANCIENT EUROPE

Iron Age, and Roman and Merovingian periods was

charged with evaluating and excavating a 237-

hectare area at Onnaing (near Valenciennes) before

the construction of a Toyota plant. Initial analysis

indicated the development of many small settle-

ments in the Late Iron Age and the earlier Gallo-

Roman period, with general abandonment of sites

before

A.D. 200 and reoccupation in one place by a

Merovingian settlement with sunken-featured

buildings (SFBs). From that time the fertile Onna-

ing plain was given over to intensive cultivation.

While this example of landscape archaeology

that allows us to situate Merovingian settlement in

a period of long duration is quite exceptional, it also

serves to underline the tentative nature of any gen-

eral conclusions one might draw today, so soon

after the Brebières excavation. The full-scale publi-

cation of more recent sites is still awaited. The infor-

mation now available is unequally distributed geo-

graphically. A great density of sites in northern

France contrasts with scarcity in western and south-

ern France.

Brebières offers an object lesson in the dangers

of drawing hasty conclusions from available data.

The excavation disclosed some thirty-one SFBs

spread out along either side of a street several hun-

dred meters long. These were small rectangular

buildings, 3 to 6 meters long and 2 to 3.5 meters

wide, with wattle-and-daub walls and thatch roofs

supported by two, four, or six wooden posts set into

the dugout floor. There were few fireplaces. Locat-

ed near a marsh, which was drained by two ditches,

this site suggested to some scholars a damp,

cramped, and squalid lifestyle, an impression that

re-enforced the theory of economic decline and cul-

tural regression following the Great Invasions.

However, it is based on only a partial investiga-

tion of the site, for work was limited to a 50-meter-

wide band whose surface had been scraped away be-

fore the archaeologists arrived. There may have

been larger surface-level buildings whose traces had

been destroyed, or that lay beyond the excavated

area. The SFBs could have been only outbuildings

used for storage or workshops, as the discovery of

such artifacts as loom weights suggests. Brebières

also has to be understood in relation to the nearby

royal villa of Vitry-en-Artois (known from written

sources), to which it probably belonged. In 1985

more SFBs were found in a rescue operation at

Vitry, as well as posthole alignments, which suggest

a ground-level timber-frame house. At Juvincourt-

et-Damary (Aisne) three such houses were excavat-

ed. The largest (15 by 5 meters) had an entrance

porch leading to two rooms, one a living room

equipped with a fireplace and the other used for

sleeping.

By the mid-1990s many timber-frame buildings

had been documented in the northern part of

France. More information about the complexities of

site evolution also has become available. It has been

suggested that Juvincourt, for example, was a ham-

let within a polynuclear village. When founded at

the beginning of the Merovingian period, it consist-

ed of several surface-level buildings with SFB out-

buildings. In the later sixth century, settlement

shifted to the north; by the mid-seventh century it

had relocated even farther north, with several

aligned buildings facing a rectangular enclosure. By

the ninth century the settlement had been aban-

doned.

Excavation of the settlement at Mondeville,

near Caen in Normandy, sheds new light on the dy-

namics of early medieval settlement and its role in

the transition from antiquity to the Middle Ages,

tying it to the evolution of funerary practice as well.

Occupied in the Iron Age, Mondeville became a

vicus (substantial rural settlement) with houses built

on solid stone foundations. By about

A.D. 300 these

houses were replaced by SFBs: small timber-and-

thatch buildings with floors dug into the bedrock.

Timber architecture remained characteristic until

about

A.D. 700, when houses with stone founda-

tions reappeared. This also may have been the time

when a church with stone foundations was built

within the settlement and burials were made around

it, a sign that the traditional separation of the living

and the dead was giving way to new Christian atti-

tudes. There is more evidence of this shift at Saleux,

in Picardy, a particularly interesting site since the

entire settlement, in use from the seventh to the

eleventh century, was excavated along with the ne-

cropolis of almost twelve hundred graves. At first

the dwellings were placed close to the river and the

dead buried on higher ground, a good distance to

the west. The burial site focused around a special

grave housed in a stone sarcophagus and protected

by a wooden structure. During the eighth century

this structure was transformed into a small timber

MEROVINGIAN FRANCE

ANCIENT EUROPE

515

church, which was later rebuilt in stone; the ceme-

tery was enclosed by a ditch. By then the village it-

self had advanced to adjoin the churchyard, provid-

ing a plausible early example of the typical medieval

village, with the living and the dead knit into a

seamless community around the parish church.

Was the Merovingian period fundamentally in

rupture with antiquity, or should more stress be laid

on elements of continuity? Did the basic patterns of

medieval life have their roots deep in this period, or

did they emerge essentially around the end of the

first millennium, after centuries of instability and

poverty? Lively debate on such critical questions has

replaced the assumption that archaeology’s role is

merely to provide artifacts that illustrate a historical

narrative (whose outline is firmly fixed by written

sources) or, at most, to fill in the gaps. In the last

decades of the twentieth century there was a funda-

mental change not only in the scale and precision of

excavation but also in the scope of the larger archae-

ological enterprise, as it has been called upon to col-

laborate with other disciplines in confronting his-

torical questions. Boundaries once thought secure

now seem fluid, as is apparent in the interaction of

those “Merovingian archaeologists” primarily con-

cerned with rural settlements and cemeteries, with

scholars working on the related problems of cities

and Christianity during this period.

URBAN AND CHRISTIAN

ARCHAEOLOGY

In 1830 concern for preserving the past, which had

been growing since the destructions caused by the

French Revolution, led France to create the Com-

mission des Monuments historiques (Historical

Monuments Commission), whose trained architects

went to work restoring medieval churches. A paral-

lel pursuit, whose origins go back to the Renais-

sance, was the study of early Christian remains, such

as carved sarcophagi and inscriptions. The French

presence in North Africa and the Near East also led

to pioneering archaeological studies of early Chris-

tian buildings, many still standing in part, in the for-

mer provinces of the Roman Empire. Because few

monuments from that time survived above ground

in France itself, interest in the heritage there was

slight before the mid-twentieth century. Change

began when the fifth International Congress of

Christian Archaeology was held at Aix-en-Provence

in 1954.

Under the influence of the great historian

Henri-Irénée Marrou, the critical centuries from

A.D. 300 to 800 were seen less as a time of deca-

dence and collapse (the “Dark Ages”) than as a dy-

namic and creative period (late antiquity) driven by

the novel forces released by Christianity. It was clear

that any attempt to study this phenomenon archae-

ologically must involve excavating cities, for they

were the heart of the early Christian world. How

had the hundred civitas capitals of Gaul, the nodal

points of the Roman administration that had be-

come in the Christian empire the seats of bishops as

well, fared with the barbarian onslaught? Much of

the evidence was hidden; the great medieval cathe-

drals were built atop complex groups of early Chris-

tian buildings. A variety of literary sources, inscrip-

tions, sarcophagi, coins, and vestiges of old

buildings offered many avenues for research. Given

the poverty of resources for excavation in France

and the lack of trained excavators and of training

programs, what could be done?

By 1986, when the International Congress of

Christian Archaeology returned to France (Lyon),

impressive progress had been made, thanks to cre-

ative and energetic scholarly enterprise and to the

growth of publicly mandated salvage archaeology.

Since the mid-1970s a group of scholars had been

meeting regularly to pursue a critical and systematic

study of all the sources, written and material, for

each of the Gallo-Roman towns that had become

episcopal seats in late antiquity. At the same time re-

search-oriented archaeologists developed focused

research programs in partnership with the Archaeo-

logical Service of the Ministry of Culture, local and

regional authorities, and businesses and private en-

thusiasts. The most thoroughgoing long-term proj-

ect has been under way in the city and canton of Ge-

neva since the 1970s, until 1998 under the

direction of Charles Bonnet. The archaeology of re-

ligious edifices has been a specialty of the Bonnet

team. Their most spectacular accomplishment was

the thorough excavation of the cathedral and its sur-

roundings, showing how a complex Merovingian

cathedral group (including a bishop’s palace with a

sixth-century mosaic pavement) developed out of

late Roman administrative buildings (fig. 2).

While it would be imprudent to draw quick

conclusions from the vast amounts of new data gen-

erated by this type of work, two general comments

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

516

ANCIENT EUROPE

Fig. 2. Mosaic from the sixth-century Bishop’s palace. PHOTOGRAPH BY MONIQUE DELLEY. COURTESY SERVICE CANTONAL D’ARCHÉOLOGIE,

GENEVA. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

can be made. First, it is clear that the urban compo-

nent of Merovingian civilization was much more

important and dynamic than once was thought and

that Christianity was the primary force in the surviv-

al and redefinition of these towns. That the over-

whelming majority of the Roman civitas capitals in

Gaul did survive as urban settlements, apparently

without any break in continuity, is a clear contrast

with the discontinuity found in Britain.

The nature and scale of survival varied dramati-

cally. It was most attenuated in Tours, once a

planned Roman town of 80 hectares. By

A.D. 500

there remained a 9-hectare walled citadel by the

river, where the bishop in his cathedral and the

count in his hall kept company. Two kilometers to

the west stood a funerary church dedicated to Saint

Martin, around which a new community, called by

a contemporary the vicus christianorum (settlement

of the Christians), was emerging. Most of the old

Roman town, between these points, had become

fields. The western pole grew rapidly, stimulated by

the popularity of Saint Martin’s tomb as a goal of

pilgrimage; it came to be enclosed within its own

wall. In Geneva, around

A.D. 500, the bishop’s

monumental new buildings were filling the walled

hilltop citadel; other new churches were revitalizing

the suburbium (the area around the core) below.

Farther out in the countryside churches were going

up as well.

This picture leads to the second general obser-

vation authorized by recent research: the Christian

impact on the rural world. At Sezegnin, about 10

miles from Geneva, a rural cemetery of more than

six hundred graves developed around three privi-

leged burials in the center. They were not “elite”

graves in the traditional social sense, for they includ-

ed almost no artifacts, but they were set off by a

wooden structure that can be interpreted as a me-

MEROVINGIAN FRANCE

ANCIENT EUROPE

517

moria, a monument to commemorate the honored

Christian dead. The fugitive traces of such a struc-

ture would have escaped attention in the past, but

there is growing evidence in the core Frankish re-

gions to the north that by the later sixth century

elite burials were shifting to unmistakable Christian

contexts.

A rural cemetery excavated at Hordain (near

Douai) shows that an emphatically un-Christian

burial style (cremation under tumulus) co-existed c.

A.D. 550 with richly furnished (weapons and orna-

ment) inhumation burials in a funerary chapel built

in the midst of the cemetery. In Belgium a private

funerary chapel at Arlon included an elite warrior

grave and that of a young woman buried sometime

around

A.D. 600 with ornaments that included a

Christian silver locket. One of the earliest well-

dated examples of richly furnished elite burials in a

Christian context (c.

A.D. 530/540) comes from

the old Roman town of Cologne, capital of the Rhe-

nish Franks. In a chapel within the atrium of the ca-

thedral a young boy was buried with weapons (in-

cluding a helmet) and furniture (bed and chair);

beside him a young woman lay with finery that rivals

that of Aregonde in Saint-Denis a generation later.

Thus both archaeological finds and written sources

associate the Merovingian elites with the towns and

stress the vitality of the Christian culture there.

Even funerary practices were beginning a gradual

shift toward what would emerge in the Carolingian

period as a fully Christian organization of death.

See also Merovingian Franks (vol. 2, part 7); Tomb of

Childeric (vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Archéologie de la France: 30 ans de découverts. Paris: Réunion

des Musées Nationaux, 1989. (Catalogue of the high-

lights of recent archaeology in France, with useful intro-

ductory essays by topic.)

Böhme, Hörst W. Germanische Grabfunde des 4. bis 5.

Jahrhunderts zwischen unterer Elbe und Loire. 2 vols.

Müncher Beiträge. Vor- und Frühgeschichte, no. 19.

Munich: C. H. Beck, 1974. (Classic study of late

Roman Germanic graves.)

Böhner, Kurt. Die fränkischen Altertümer des Trier Landes.

2 vols. Berlin: Germanische Denkmäler der Völker-

wanderungzeit, 1958. (First regional relative artifact

chronology.)

Bonnet, Charles. Genève aux premiers temps chrétiens. Gene-

va, Swizerland: Fondations des Clefs de Saint Pierre,

1986.

Catteddu, Isabelle. “Le site médiévale de Saleux ‘Les Cou-

tures’: Habitat, nécropole, et églises du haut Moyen

Age.” In Rural Settlements in Medieval Europe. Edited

by Guy De Boe and Frans Verhaeghe, pp. 143–148. Pa-

pers of the 1997 Medieval Europe Brugge Conference,

vol. 6. Zellik, Belgium: Institute for the Archaeological

Heritage, 1997.

Colardelle, Michel. Sépulture et traditions funéraires du Ve

au XIIIe siècle ap. J.C. dans les campagnes des Alpes

françaises du Nord (Drôme, Isère, Savoie, Haute-

Savoie). Grenoble, Switzerland: Societé Alpine de Do-

cumentation et de Recherche en Archéologie, 1983.

(Regional study, integrating artifacts and funerary prac-

tices for relative chronology.)

Effros, Bonnie. Merovingian Mortuary Archaeology and the

Making of the Early Middle Ages. Berkeley: University

of California Press, 2003.

Die Franken: Wegbereiter Europas. 2 vols. Mainz, Germany:

Verlag Philipp Von Zabern, 1996. (Catalogue from the

Reiss-Museum, Mannheim, of largest exhibition ever

held of Frankish archaeology, with many fundamental

articles by leading scholars.)

Galinié, Henri. “Tours from an Archaeological Standpoint.”

In Spaces of the Living and the Dead: An Archaeological

Dialogue. Edited by Catherine Karkov, Kelley Wick-

ham-Crowley, and Bailey Young, pp. 87–106. Ameri-

can Early Medieval Studies, no. 3. Oxford: Oxbow

Books, 1999.

Geary, Patrick J. Before France and Germany: The Creation

and Transformation of the Merovingian World. Oxford:

Oxford University Press, 1988.

Halsall, Guy. “Burial, Ritual, and Merovingian Society.” In

The Community, the Family and the Saint: Patterns of

Power in Early Medieval Europe. Edited by Joyce Hill

and Mary Swan, pp. 325–338. Turnhout, Belgium:

Brepols, 1998.

———. Settlement and Social Organization: The Merovin-

gian Region of Metz. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge

University Press, 1995.

James, Edward. The Franks. Oxford: Blackwell, 1988.

———. The Merovingian Archaeology of South-west Gaul.

BAR Supplementary Series, no. 25. Oxford: British Ar-

chaeological Reports, 1977.

Lorren, Claude. “Le village de Saint-Martin de Traincourt

à Mondeville (Calvados), de l’Antiquité au Haut

Moyen Age.” In La Neustrie: Les pays au nord de la

Loire de 650 à 850. Vol. 2. Edited by Hartmut Atsma,

pp. 439–466. Sigmaringen, Germany: Thorbecke,

1989.

Martin, Max. Das fränkische Gräberfeld von Basel-

Bernerring. Basel, Switzerland: Basler Beiträge zur Ur-

und Frühgeschichte, 1976.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

518

ANCIENT EUROPE

Mertens, Joseph. Tombes mérovingiennes et églises chrétiennes

(Arlon, Grobbendonk, Landen, Waha). Archaeologica

Belgica, no. 187. Brussels, Belgium. 1976.

Musset, Lucien. The Germanic Invasions: The Making of Eu-

rope,

A.D. 400–600. Translated by Edward and Columba

James. University Park: Pennsylvania State University

Press, 1975. (A still pertinent overview of the period;

excellent bibliography to 1975.)

Naissance des arts chrétiens: Atlas des monuments paléochré-

tiens de la France. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1991.

(Lavishly illustrated interpretative survey by leading

scholars.)

Périn, Patrick. “Settlements and Cemeteries in Merovingian

Gaul.” In The World of Gregory of Tours. Edited by

Kathleen Mitchell and Ian Wood, pp. 67–98. Leiden,

The Netherlands: Brill, 2002.

———. “Les tombes de ‘chefs’ du début de l’époque

mérovingienne: Datation et interprétation historique.”

In La noblesse romaine et les chefs barbares du IIIe au VIe

siècle. Edited by Francoise Vallet and Michel Kazanski,

pp. 247–301. Association Française d’Archéologie

Mérovingienne Mémoires, no. 9. Saint-Germain-en-

Laye, France: Musée des Antiquités Nationales, 1995.

———. La datation des tombes mérovingiennes: Historique,

méthodes, applications. Geneva, Switzerland: Droz,

1980. (Fundamental for the history and methodology

of funerary archaeology.)

Périn, Patrick, and Laure-Charlotte Feffer. Les Francs, de

leur origine jusq’au 6ème siècle, et leur heritage. 2 vols.

Paris: Armand Colin, 1997. (Vol. 1, A la conquête de la

Gaule; vol. 2, A l’origine de la France. Well-illustrated,

accessible overview with archaeological emphasis.)

Peytremann, Edith. Archéologie de l’habitat rural dans le

nord de la Gaule du IVe au XIIIe siècle. 2 vols. Associa-

tion Française d’Archéologie Mérovingienne Mé-

moires, no. 13. Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France: Musée

des Antiquités Nationales, 2002. (The first general

study of the subject, with a complete site catalogue.)

Pilet, Christian. La nécropole de Frénouville: Étude d’une po-

pulation de la fin du IIIe à la fin du VIIe siècle. 2 vols.

BAR International Series, no. 83. Oxford: British Ar-

chaeological Reports, 1983.

Privati, Béatrice. La nécropole de Sézegnin (Ive–VIIe siécle).

Société d’Histoire et d’Archéologie de Genève, no. 10.

Geneva, Switzerland: A. Jullien, 1983.

Salin, Édouard. La civilisation mérovingienne d’après les sé-

pultures, les textes et le laboratoire. 4 vols. Paris: A. and

J. Picard, 1950–1959. (Vol. 1, Les idées et les faits; vol.

2, Les sépultures; vol. 3, Les techniques; vol. 4, Les croy-

ances. Although dated and much criticized, still a funda-

mental work by the pioneer of twentieth-century Mero-

vingian archaeology in France.)

Sapin, Christian. “Architecture and Funerary Space in the

Early Middle Ages.” In Spaces of the Living and the

Dead: An Archaeological Dialogue. Edited by Catherine

Karkov, Kelley Wickham-Crowley, and Bailey Young,

pp. 39–60. American Early Medieval Studies, no. 3.

Oxford: Oxbow Books, 1999.

Young, Bailey K. “The Myth of the Pagan Cemetery.” In

Spaces of the Living and the Dead: An Archaeological

Dialogue. Edited by Catherine Karkov, Kelley Wick-

ham-Crowley, and Bailey Young, pp. 61–85. American

Early Medieval Studies, no. 3. Oxford: Oxbow Books,

1999.

———. “Les nécroples (IIIe–VIIIe siècle).” In Naissance des

arts chrétiens: Atlas du monde paleochrétien. Paris: Im-

primerie Nationale, 1991. (Includes extensive site bibli-

ography.)

———. “Paganisme, christianisation, et rites funéraires

mérovingiens.” Archéologie médiévale 7 (1977): 5–83.

(Includes site gazetteer.)

B

AILEY K. YOUNG

■

TOMB OF CHILDERIC

On 27 May 1653 a deaf-mute mason named Adrien

Quinquin, working on a construction project near

the church of Saint-Brice in Tournai, Belgium,

struck gold. As the abbé Cochet reconstructs the

story in Le tombeau de Childéric I, he was down

about 7 or 8 feet in dark earth when a chance blow

of the pick suddenly revealed a gold buckle and at

least a hundred gold coins. This surprise find caused

him to throw down the tool and run about, waving

his arms and trying to articulate sounds. The first

witnesses who crowded around the trench saw some

two hundred silver coins; human bones, including

two skulls; a lot of rusted iron; a sword with a gold

grip and a hilt ornamented in the gold-and-garnet

cloisonné technique and sheathed in a cloisonné-

decorated scabbard; and numerous other gold

items, among them, brooches, buckles, rings, an or-

nament in the form of a bull’s head, and about three

hundred gold cloisonné bees.

The authorities acted quickly to gather together

this “treasure,” and news of it soon reached the

archduke Leopold William, governor of the Austri-

an Netherlands, who had it sent to him in Brussels.

He further ordered that a careful written account of

the find be made and confided the collection for

study to his personal physician, Jean-Jacques Chif-

TOMB OF CHILDERIC

ANCIENT EUROPE

519

Fig. 1. Childeric’s “treasure” from original 1655 plates: weapons. FROM VALLET AND KAZANSKI 1995.

REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

flet, who also was a historian. The outstanding find

was a gold signet ring inscribed with the figure of

an armed warrior and the name CHILIRICI

REGIS. In 1655 Chifflet published a folio volume

of 367 pages with 27 plates of engravings furnishing

an excellent visual record of all the artifacts and a

careful discussion and interpretative essay identify-

ing the subject as the father of Clovis I, the great an-

cestor of the French monarchy. This discovery is the

starting point of Merovingian archaeology, and

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

520

ANCIENT EUROPE