Bogucki P., Crabtree P. Ancient Europe 8000 B.C.-A.D. 1000: Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World. Volume 2

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

goats, hens, horses, dogs, and cats. Hunting equip-

ment and faunal remains of wild game indicate that

beaver, fox, hare, moose, deer, wolf, lynx, seal, vari-

ous birds, and numerous fish were hunted, some for

food and some for their pelts.

SOCIETY AND CULTURE

Many ethnic groups lived in early medieval Staraya

Ladoga, among them, Balts, Finns, Slavs, and Scan-

dinavians. These groups are distinguished more eas-

ily in the early centuries of settlement. Over time,

the material culture of Staraya Ladoga became more

homogenized. Archaeological research on burials

throughout the Lake Ladoga region suggests that

ethnic integration existed inside and outside the

town. Although it is also known as Russia’s first

“capital,” Staraya Ladoga is best characterized as a

multi-ethnic trade town whose residents participat-

ed in the international Baltic Sea trade network.

See also Rus (vol. 2, part 7); Russia/Ukraine (vol. 2, part

7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Clarke, Helen, and Björn Ambrosiani. “Towns in the Sla-

vonic-Baltic Area.” In their Towns in the Viking Age, pp.

107–127. Rev. ed. Leicester, U.K.: Leicester University

Press, 1995.

Uino, Pirjo. “On the History of Staraja Ladoga.” Acta Ar-

chaeologica 59 (1988): 205–222.

R

AE OSTMAN

STARAYA LADOGA

ANCIENT EUROPE

571

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

HUNGARY

■

Hungary, the central third of the 300,000-

kilometer Carpathian Basin, is divided by the Dan-

ube River. The western hilly region (100–600 me-

ters above sea level) is called Transdanubia. The

marshy grasslands of the Great Hungarian Plain oc-

cupy most of the eastern half. Located at a geopolit-

ical fault line between central Europe and the Eur-

asian steppe, and marked by a major river as well as

a topographic interface, the Carpathian Basin has

been divided periodically since prehistory. The his-

toric east-west difference may be detected even

today.

From the first century

A.D., the paths of Ger-

manic migrations from the north and of Asiatic peo-

ples from the east crossed here in the Barbaricum

and, later, over the ruins of the Roman province of

Pannonia, leaving overlapping archaeological im-

prints that made the Migration period one of the

least tangible archaeological ages in the region.

These peoples are stereotypically described as mo-

bile “nomads,” best known for their spectacular

pieces of portable art. Germanic peoples for whom

there is the best evidence in the Carpathian Basin

between the first and mid-sixth centuries included

Quadi, Vandals, Gepids, Skirs, Goths, and Lango-

bards. Some arrived from the north, and others fol-

lowed a detour through the eastern European

steppe, from where Asiatic Sarmatians, Alans, and

Huns also came. After the late sixth century, Avars,

Bulgars, Hungarians, and Cumanians all moved in

from Asia. By that time Slavic territory surrounded

the Carpathian Basin. Details of this geopolitical

picture developed in a subtle chronological se-

quence. Heterogeneous archaeological sources and

emotionally charged historical stereotypes provide

only a fuzzy picture of “barbarians,” often open to

alternative interpretations.

SOURCES FOR THE

MIGRATION PERIOD

Migrations left an archaeological record in Hungary

that ranges from scarce settlement remains to spec-

tacular hoards. Most field information, however,

originates from burials. Most coeval documents

chronicled historical events and the life of elites.

Our image of barbarians is secondhand, influenced

by the ethnocentrism of classical Greek, Roman,

Byzantine, or Arabic authors. The word “barbar-

ian” derives from the Greek barbaros, meaning

“strange” or “foreign.”

Interpretations have varied as research has

evolved. In conventional terms, the Migration peri-

od in Hungary lasted from

A.D. 271, when Romans

ceded the province of Dacia, to 895, the date of the

Hungarian conquest. Archaeologically, however, its

beginnings and consequences span well over a mil-

lennium. While the historical chronology of barbar-

ian groups is relatively clear, landmark events in the

written record do not necessarily mean sudden inva-

sion or complete disappearance of peoples. Mobility

depended on the motivations and composition of

migrants. Because the length of time that groups

stayed also varied, their material cultures are diffi-

cult to compare. It is the historical model, therefore,

that usually is refined based on stylistic differences

between archaeological artifacts.

572

ANCIENT EUROPE

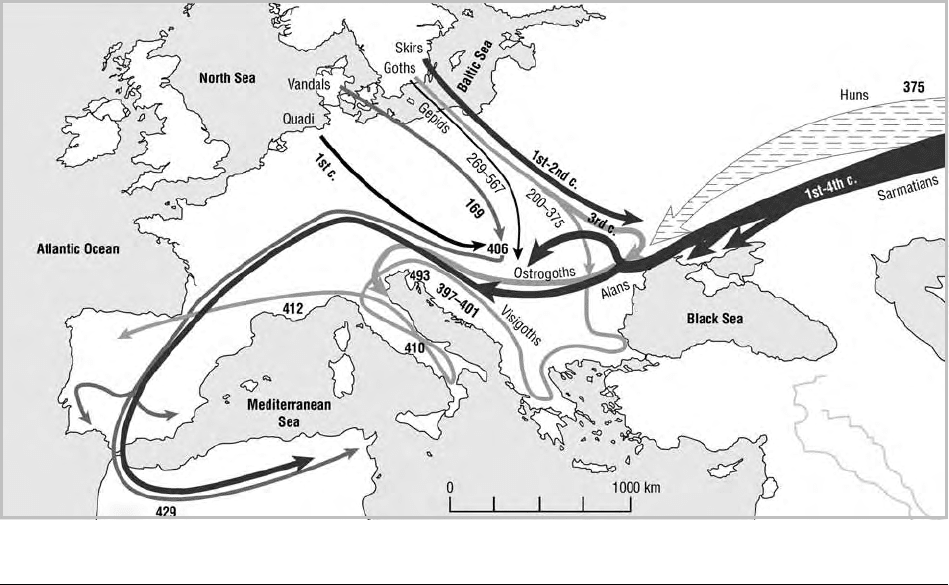

Early Migration period population movements. The migration routes of northern and eastern Germanic tribes as well as Asiatic

peoples crossed in the Carpathian Basin. DRAWN BY LÁSZLÓ BARTOSIEWICZ.

Fine-grained absolute chronologies would be

fundamental in the archaeology of this hectic peri-

od. Poor wood preservation in Hungary limits the

use of dendrochronology. Radiocarbon dating, on

the other hand, is somewhat inaccurate for later pe-

riods. “Typochronology,” that is, the interpretation

of culture change and ethnic relations using the rel-

ative chronology of artifact styles, thus has become

the ruling paradigm in Migration period research.

Weaknesses in this method are inherent to the finds:

various groups are represented by different types of

assemblages ill suited to direct comparison. Settle-

ment remains tend to be few and far between, and

the comprehensive analysis of cemeteries sometimes

is difficult in the absence of proper physical anthro-

pological information. Moreover, high-status grave

goods may have remained in use for generations and

were circulated over long distances. Antiquarians

dug up spectacular hoards during the late eigh-

teenth and nineteenth centuries, before the impor-

tance of stratigraphic information was recognized.

No researcher can afford to ignore these unique as-

semblages, but interpretations often are difficult to

fit into a systematic picture.

ROMAN PERIOD BARBARICUM

Even before the first-century establishment of the

Roman province of Pannonia, inhabited at the time

by “native” Celtic tribes, Transdanubia was linked

closely to central Europe. The Danube served as a

natural boundary for the Roman Empire. During

the second and third centuries, the Barbaricum in

the Great Hungarian Plain and areas to its north

were wedged between Pannonia and the mountain-

ous Roman province of Dacia. Having defeated the

Scythians in southern Russia, Sarmatian tribes

reached the Barbaricum during the first century as

mercenaries for the Quadi, the first northern Ger-

manic group to set foot in the Carpathian Basin.

The Sarmatian light cavalry, covered head to toe by

fish-scale-like armor, is depicted on Trajan’s Col-

umn from

A.D. 110–113.

Owing to their large population and prolonged

presence, Sarmatians are well known from settle-

ment excavations, beyond burials or documented

movements. Rural settlements in the Barbaricum

show that within a few generations they became

sedentary and adopted local technical skills. There-

after, traditional artifacts from the east indicate an-

HUNGARY

ANCIENT EUROPE

573

other Sarmatian wave. At the turn of the second

century, after the Roman occupation of Dacia, Sar-

matians spread across the Great Hungarian Plain.

Ubiquitous Sarmatian pits dot an entire archaeolog-

ical time horizon there.

Meanwhile, the Quadi moved south from their

first-century territory and remained allied with Sar-

matians facing the Romans across the Danube.

Hectic relations between Romans and barbarians

culminated in two decades of Marcomannic/

Sarmatian wars, starting in the

A.D. 170s. Finally,

the Romans pacified the barbarians and created the

province of Sarmatia. Finds show that trade contacts

intensified: Roman goods of all sorts, including

stamped pottery and a variety of jewelry, commonly

occur at Sarmatian sites in the central Great Hun-

garian Plain. Large, barrel-shaped chalcedony beads

may be found in Sarmatian women’s graves, and en-

ameled brooches show Celtic influence. Sarmatian

pastoralists possibly bartered livestock and food-

stuffs for such luxury goods. Weapons as well as set-

tlement features reflect the advanced Sarmatian

ironworking.

Vandals were the next northern Germanic

group to come after the Marcomannic wars. They

occupied northeastern Hungary and raided Roman

provinces in the third to fourth centuries. Allied

with Iranian-speaking Alans, they moved on to dev-

astate Gaul (406–409), Iberia (409), North Africa

(429), and Rome itself (455). Archaeologically, this

group is known from burials in the Carpathian

Basin. Celtic and Roman decorative art influenced

the northern stylistic tradition of their grave goods.

Artifacts from “royal” graves of the third to fourth

centuries in Ostrovany (Slovakia), found in 1790

and 1865, respectively, have been linked with this

group.

The consolidation of China during the third

century, along with the hypothesized deterioration

of steppe environments, drove Asiatic Huns west-

ward. They crossed the Volga River during the early

370s, forcing eastern Germanic peoples (Goths and

Skirs from Scandinavia, who had reached the steppe

across the Baltic during the first century

A.D.) into

the Carpathian Basin. During their westward move-

ment, the Goths, the strongest and most adventur-

ous of the Germans, raided many parts of the

Roman Empire throughout the third to fifth centu-

ries. Their eastern confederacy, Ostrogoths, spent

twenty years in Pannonia before forming a kingdom

in Italy (493). Western Visigoths were driven into

the Balkans in the late fourth century, from where

they sacked Rome in 410 and established a kingdom

in present-day Spain and southern France.

Skirs surfaced for only a short time in the Carpa-

thian Basin, in alliance with the Huns. The burials

of two high-ranking ladies and another woman

found in Bakodpuszta were associated with this

eastern Germanic tribe. Gold and silver jewelry

from these graves postdates Hun rule in the area.

(Skirs rose to historical fame when their king

Odoaker delivered a coup de grâce to the western

Roman Empire by occupying Rome in 476.)

Sarmatians fought bitterly with Germans along

their eastern borders during the fourth century and

even built a 1260-kilometer-long system of ditches

and earthworks, possibly with Roman help, along

the northeastern edge of the Great Hungarian

Plain. In Pannonia stylistic evidence from potsherds

suggests that starting in the 370s, Romans enlisted

Hun, Alan, and Germanic foederati (mercenaries

who retained their tribal organization but acknowl-

edged Roman supremacy) in the defense of the ail-

ing province.

EARLY MIGRATION PERIOD

In 271, the year the Romans ceded Dacia to the

Goths, Gepids occupied the upper reaches of the

Tisza River. Following the uneasy coexistence of

German tribes and Asiatic Sarmatians, as well as

Alans neighboring the Roman Empire in the Carpa-

thian Basin, a new Hun invasion reached Hungary

in the first third of the fifth century. Renewed incur-

sions by Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Vandals, and Alans

(to name but a few) into the Carpathian Basin and

the Roman Empire itself were, in part, a conse-

quence of Hunnic expansion. Between 400 and 402

Huns invaded southern Poland, forcing out Ger-

manic tribes and thereby opening up space for sub-

sequent Slavic settlement. During the 410s, their

power center moved into the Great Hungarian

Plain through the Lower Danube region. Negotia-

tions with the Romans also provided Hun foederati

access to Pannonia. By this time, haphazardly re-

built fortifications and intramural burials bear wit-

ness to the disintegration of Roman power along

the Pannonian limes.

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

574

ANCIENT EUROPE

Huns organized a tribal confederation in the

Carpathian Basin, uniting peoples on the basis of

Roman foederati rights, filling a geopolitical vacu-

um between the competing western and eastern

Roman Empires. Between 441 and 452 Huns con-

ducted military campaigns in both directions, short

of invading Rome itself. After the death of their

king, Attila (in 453), however, allies rose and de-

feated the Huns under the leadership of the Gepids

in 454, ending Hun rule in the Carpathian Basin.

The Hun empire that existed for only a single

generation yielded numerous artifacts, many of

which are commonly associated with oriental, war-

like equestrian peoples but came to light as stray

finds. Grave goods include metal fittings from high

saddles as well as ears of powerful reflex bows (the

extreme ends serving for chord attachment, made

from antler or bone), double-edged swords, and

long combat knives. Gold decoration on these and

numerous utilitarian objects, as well as precious

metal jewelry acquired as war booty or by punitive

taxing, reflect the heyday of the Hun empire. Iden-

tifying “Hun” artifacts is difficult because this em-

pire united numerous ethnic groups whose material

cultures were similar at the outset. Artifacts were

mixed further by diffusion and exchange. After the

collapse of the Hun empire, many former vassals

formed small “kingdoms.” Huns fled toward the

Pontic region, from where Ostrogoths came into

the Carpathian Basin following a treaty with Byzan-

tium. Archaeologically, this development is shown

by jewelry displaying the classic stylistic features of

Pontic metal workshops. One technique employed

violet-red almandine or garnet in combination with

enamel inlay. The Ostrogoths first moved eastward

from southern Pannonia in 473 and then left for

Italy in 489.

Eastern Germanic Gepids left Scandinavia and

regrouped with the Goths in the area of present-day

Poland during the Roman period. Pliny, who first

mentioned the Goths, placed them in northern Ger-

many. The historian Jordanes in his Origin and

Deeds of the Goths, however, named their homeland

as Scandinavia. Linguistic evidence may suport this,

although the Scandinavian origin of the Goths is

still impossible to prove. Archaeological evidence

points to the Goths having slowly migrated from

the Oder-Vistula region to the Ukraine and Scythia.

In the Carpathian Basin they established rural settle-

ments north of Dacia in 269.

Gepids contributed a major contingent to the

Hun army during the mid-fifth century, led the

usurpation of power that followed Attila’s death,

and expanded toward the south and east: Sirmium

(Mitrovica, Serbia), a Roman imperial town, be-

came the Gepid capital. Important finds of Gepid

aristocracy in Transylvania include the royal graves

of Apahida and the Szilágysomlyó (S¸imleul Silva-

niei, Romania) hoards, discovered in 1797 and

1889, respectively, and consisting of Roman memo-

rial gold medallions as well as gold and gilded silver

brooches. Gepid cemeteries from the late fifth and

sixth centuries contain hundreds of graves. Because

many have been robbed, however, they are of limit-

ed help in reconstructing socioeconomic differ-

ences. High-ranking warriors were buried with long

and short swords as well as lances and shields. Com-

moners were interred with silver and bronze

brooches and other clothing accessories. Eagle-

headed buckles seem to have been a favorite fashion

item. It is possible that Christianity also reached this

population through Gothic missionaries during the

fourth century. This hypothesis is supported by cru-

cifix motifs in their decorative art. Certain settle-

ment excavations have revealed Gepid houses and

adjoining sheds and workshops, containing artifacts

related to both household and craft activities.

Wheel-thrown, evenly fired, fine Gepid pottery with

stamped decoration represents the Celtic-Sarmatian

tradition.

After a second-century incursion, the Lango-

bards entered the Carpathian Basin from the north

in about 510 and took over urbanized northern

Pannonia from other Germanic peoples in 526. At

the beginning, they coexisted peacefully with

Gepids, who at that time controlled the Great Hun-

garian Plain and Transylvania. In 535, however,

Langobards forged an alliance with Byzantium that

allowed them access to southern Pannonia, where

they faced Gepids expanding westward. Decades of

military skirmishes followed. After 565 Byzantine

contacts with the Gepids improved, so that Lango-

bards turned for help to the central Asian Avars,

who had just started exploring the possibilities of

westward expansion into the Carpathian Basin.

From 562 onward, the supreme leader (khagan) of

the Avars was Bayan Khan, comparable to Attila the

HUNGARY

ANCIENT EUROPE

575

Hun in political stature. The Langobard-Avar alli-

ance defeated the Gepids in 567. Part of the agree-

ment seems to have been that Langobards had to

leave Pannonia for Italy the following year.

Langobards were the last Germanic group to

rule in the Carpathian Basin. Their material culture

in Pannonia is known exclusively from burials.

Given the history of Langobard occupation in

Transdanubia, the ethnic composition of these cem-

eteries is complex. Men’s burials contained large,

double-edged swords, lances, and shields. Women

were accompanied by gilded silver jewelry, includ-

ing brooches decorated with northern as well as

eastern stylistic elements.

THE LATE MIGRATION PERIOD

The appearance of Avars in the Carpathian Basin in

the last third of the sixth century heralded a new era

of centralized rule that united the Carpathian Basin

for almost a quarter of a millennium. This is not to

say, however, that Avars were an ethnically homo-

geneous population. The core groups of inner and

central Asian extraction were first allied with Byzan-

tium, whose protection they sought against Turkic

groups that had forced them westward. As Lango-

bards left for Italy in 568, the consolidation of Avar

power began. Large cemeteries from the early Avar

period in Transdanubia (Budakalász, Kölked A-B,

Környe, and Zamárdi) suggest that the center of the

emerging empire was in Pannonia. Aside from Avar

finds, such as belt sets, globular earrings, and bead

necklaces, grave goods reflect Germanic contacts.

The first sixty years of the Avar empire saw con-

flicts with Byzantium over Dalmatia and Thrace.

Avars occupied the former Gepid capital of Sirmium

in 582 and Singidunum (present-day Belgrade) in

584. Avars encouraged the settlement of northern

Slavic allies around their empire, to buffer outside

attacks. Merovingian contacts are evident from the

early seventh century, with other Germanic connec-

tions. Amid confrontations and peace treaties, Avars

extorted money and gold from Byzantium, whose

military priority was securing its eastern border

against the Persians. Although some gold solidus

coins found in Hungary were trimmed around the

edges, an estimated 20 metric tons of Byzantine

gold may have reached the Avar empire. In 626

Avar troops laid siege to Constantinople (modern-

day Istanbul) in alliance with the Persian navy, al-

though the two forces failed to unite. At that point,

the Byzantine emperor Heraclius had had his fill of

Avar intimidation and crushed the land offensive.

Thereafter, as far as Byzantium was concerned,

Avars ceased to exist as a political entity. Trying to

compensate for lost revenue, Avars plundered

Forum Iulii (Cividale, Lombardy) in 628, straining

relations with their western, Germanic allies. There-

after, they were confined to the Carpathian Basin.

Their Slavic and Bulgar vassals also rebelled, weak-

ening the empire from the inside.

Finds from both intact and looted high-status

burials in the Great Hungarian Plain (Bócsa, Tépe,

Kunágota, and Kunbábony) show that the Avar

power center shifted from the right bank of the

Danube toward the east during the first half of

the seventh century. While the exact social status of

the deceased is difficult to establish, there is little

doubt that these burials represent the top of the

Avar social hierarchy (fig. 1). All graves stood alone,

with no permanent markers, such as burial mounds

or tombstones. Accompanying burials of complete

warhorses was not merely a privilege accorded to

leaders; horse skeletons also occur in common war-

riors’ graves. Thanks to the prolonged presence of

Avars in the Carpathian Basin, in addition to fifty

thousand known burials, there have been discover-

ies of several of their rural settlements, such as the

150 semi-subterranean houses identified at Kölked.

Early Avar weaponry, horse harness elements,

and utilitarian objects tend to reflect oriental tradi-

tions, whereas jewelry and other high-status items

in treasures (golden bowls and jugs and glassware,

for example) represent a variety of artistic elements

dominated by late antique and especially Byzantine

influences. In comparison with early Avar cemeter-

ies in Transdanubia, however, grave goods in large

cemeteries of the Great Hungarian Plain (e.g.,

Tiszafüred–Majoros) show the declining impact of

Mediterranean material culture. This duality in arti-

fact styles confirms written accounts of early Avar

history in the Carpathian Basin.

By the late seventh century the initial absence

of jewelry and gold objects in graves may be ex-

plained by severed Byzantine contacts. In addition

to a shift in the orientation of burials, grave goods

also changed. These phenomena coincided with the

reappearance of Byzantine stylistic features in the

grave furniture. Such burials seem to mark the arriv-

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

576

ANCIENT EUROPE

al of the Onogur-Bulgarians, a group of Turkic pas-

toral peoples. They had inhabited the northern

Pontic region after 463, until the Khazars destroyed

their empire around 670. Some fled to the Lower

Danube region, and others reached the Avar empire

but maintained intensive contacts with Byzantium.

Large Avar cemeteries from this time, together

with evidence for sedentism in settlement materials,

suggest that ethnic changes took place peacefully,

presumably with the consent of the khagan. Histor-

ical sources reveal no major military events in the in-

creasingly isolated Avar empire until the end of the

eighth century. Burials suggest that equestrian life-

styles were maintained only by the ruling elites, and

agriculture seems to have become a dominant occu-

pation among commoners of mixed ethnicity. The

integrity of burial rites appears to have declined, and

some grave assemblages display signs of impoverish-

ment. A marked change in grave goods is that the

pressed metal fittings in men’s belt sets were re-

placed by molded, usually bronze equivalents. Their

acanthus motifs gave way to the so-called “griffin

and meander” motif. This style was developed to

perfection within the Carpathian Basin from evi-

dently Eurasian/Byzantine roots. Floral elements

replaced the initial animal fight motifs toward the

late eighth century.

Gold objects in the so-called Nagyszentmiklós

hoard (Sînnicolaur Mare, Romania), discovered in

1799, display an unusual richness of stylistic ele-

ments, dating from the seventh to eighth centuries

on a typological basis. Interpretations of this twen-

ty-three-piece “table set” have varied considerably.

Researchers largely have accepted that its details re-

veal the complexity of Avar period mythology, reli-

gion, and possibly writing. Its details reflect Byzan-

tine and Sassanian influences, illustrating the rich

universe of what is considered late Avar culture

today.

After the conquest of Lombardy (774) and the

military campaign on Saxony (772–785) by the

Frankish king Charlemagne, Frankish expansion

from the west first hit the Avar empire in 788. Mili-

tary campaigns in 791 and 795, together with vi-

cious infighting, weakened the Avars to such an ex-

tent that an additional military thrust by Bulgar

forces from the south in 804 destroyed their empire.

Following these defeats, Charlemagne assigned the

territory “Avaria” in 805, between Savaria (Szom-

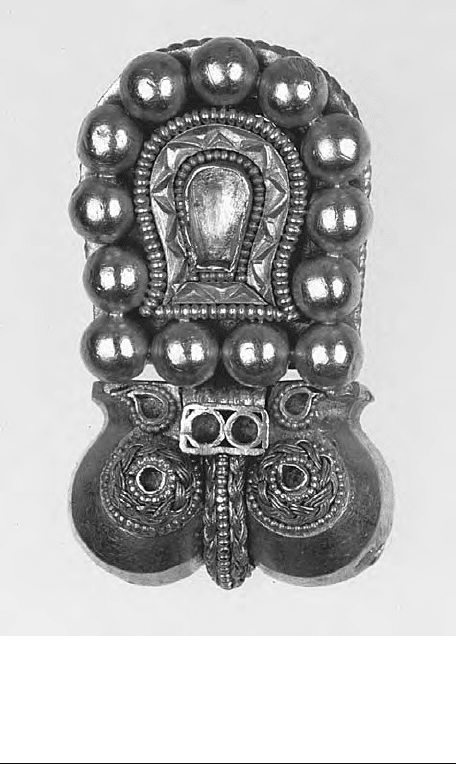

Fig. 1. Avar Period “fake” golden buckle from a robbed grave

in Tèpe, Hungary, mid-seventh century. High-status grave

goods have been instrumental in the attempted

reconstruction of Avar history. PHOTOGRAPH BY ANDRÁS DABASI.

HUNGARIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM. REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION.

bathely) and Carnuntum (Deutsch-Altenburg). Of

the Avar khagans Theodor was baptised in 803 and

Abraham in 805. The Carpathian Basin again be-

came divided: Bulgars took over the eastern section

and raided southeastern Pannonia (826–829), dis-

persing the remaining Avar population. The rest of

Pannonia fell into the Carolingian sphere of inter-

est. Avar peoples in western Hungary are last men-

tioned in 871, as the taxpayers of the Frankish king.

During the 840s the Franks settled the Slavic

chieftain Pribina in Mosaburg (Zalavár) in Panno-

nia. Although his position as head of a “Slavic state”

there needs to be confirmed, he undoubtedly ruled

an area whose Slavic population had increased in the

wake of the Avar period. Pribina and his heir, Kocel,

along with Bavarian settlers, may have represented

Carolingian rule in the area. Archaeological finds

display both Moravian and Carolingian stylistic in-

HUNGARY

ANCIENT EUROPE

577

fluences. It appears that Pannonia was largely under

Frankish rule between the fall of the Avar empire

and the Hungarian conquest.

THE HUNGARIAN CONQUEST

In written sources Hungarians figure as yet another

pastoral group from the steppe, often mistaken for

Scythians, Turks, or Onugrians. The Magyars did

not use the latter name, applied to both Bulgarians

and Magyars (i.e., Hungarians), in reference to

themselves. During the mid-sixth century eastern

Turkic peoples triggered another wave of migra-

tions that brought new peoples to the border be-

tween central Asia and Europe. Groups inhabiting

the parkland steppe to the north, including the

Finno-Ugric–speaking Magyars, also left their

homelands for the steppe, which was economically

more developed than the Ural region. There are

similarities between burials of the sixth to eighth

centuries in the Volga and Ural River interfluve and

the tenth-century Magyar graves in Hungary. Sub-

sequently, Magyars moved west of the Khazar

Khanate north of the Caucasus, where they devel-

oped ties with Onogur-Bulgars. Around 850 the

Magyars moved farther west, into the Etelköz sec-

tion of the Dnieper River, seeking independence

from the Khazar Khanate. It was there that artifact

styles known from burials and settlements of the

conquering Magyars in the Carpathian Basin seem

to have consolidated.

In 862 Magyars scouted the Carpathian Basin,

attacking the eastern Frankish empire. In 881 they

returned to join the Moravians against the Franks

and then led incursions into Transdanubia (894).

Finally, with Turkic Bulgars and Pechenegs on their

heels, the entire Magyar tribal alliance, lead by the

grand duke Árpád, crossed the Carpathians into the

Great Hungarian Plain in 895. The occupation of

Pannonia in 900 reunited the Carpathian Basin.

The first equestrian burial from the Magyar con-

quest period was found at Ladánybene–Benepuszta

in 1834. The next such burial was discovered at

Vereb in 1853, and others soon followed. At the

time, however, tenth-century cemeteries of com-

moners were thought to represent slaves or local

Slavs.

Magyar material culture cannot be regarded as

a straight continuation of the Avar heritage, al-

though the skull and feet of horses sometimes were

included in the graves, possibly as part of the hide.

Goldsmithing is well represented by gilded purse

covers (e.g., Tiszabezde), some of which may have

been made in Etelköz. The style, however, flour-

ished in Hungary. A floral pattern, the so-called pal-

metta motif, became widespread during the con-

quest period. Burials also contain objects reflecting

ancient beliefs. Bone stick handles carved in the

shape of owls’ heads were found at Hajdúdorog and

Szeghalom.

The mass of precious metal acquired through

vicious military campaigns, starting with Italy in

899, gave goldsmithing impetus. The next three

fourths of the tenth century became known as the

“period of raids.” Magyar horsemen destroyed

Great Moravia (902) and then turned on the rest of

Europe, especially the German provinces, reaching

Burgundy in 913 and Bremen in 915. In 924 Mag-

yars simultaneously plundered Italy in the south and

Saxony in the north and reached the Atlantic coast

as well. It was only the desert that halted their west-

ernmost raid toward the Caliphate of Córdoba

(942), and they repeatedly threatened Byzantium

(934, 943, 958, 963, and 970) in the east. Military

success was related to the mobility of their cavalry

compared with the ponderous armies they faced.

Aside from brutality, logistical support for such far-

reaching campaigns would have been impossible

without shrewd diplomacy: not even the most for-

midable cavalry could have covered such distances

crossing purely enemy territory. Raids contributed

to the wealth of chieftains and their military entou-

rage. Precious metal artifacts of foreign origin, how-

ever, hardly ever occur in Magyar graves. One possi-

bility is that they were melted down.

A devastating defeat by Germans near Augs-

burg ended westward aggression in 955. Magyars

attacked Byzantium until their ultimate conquest in

972. By that time a network of agricultural settle-

ments had developed in Hungary, as the elite war-

riors of the old order began losing prestige and eco-

nomic power. These hardships started transforming

a mobile Asiatic horde into an established European

kingdom.

Hungary was caught between east and west

even in peacetime. After 940, a group of Magyar

leaders led by Bultsu was baptized in Constantino-

ple. Constantine Porphyrogenitus (Constantine

VII, 913–959) stood as godfather. The Byzantine

7: EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

578

ANCIENT EUROPE

influence among the Magyars was concentrated east

of the Tisza River.

In 974, however, the grand duke Géza turned

to the Holy Roman Empire and converted to west-

ern Christianity, thereby steering the development

of his people into the European Middle Ages. After

his death, his son István I was crowned in 1000 as

the first Christian king of Hungary. The adoption

of western Christianity changed material culture.

The colorful eastern style disappeared, and ancient

beliefs were suppressed. In return for pacification

and ideological changes, Magyars survived as a po-

litical entity in the Carpathian Basin.

Hungary, however, still faced barbarian threats

on the fringes of Europe for centuries. Incursions by

Pechenegs and other, smaller groups continued,

and “pagan” Magyars also rebelled from within

against the new order. Consolidation took several

generations. During the 1222–1223 campaign of

the Mongol leader Genghis Khan, Turkic-speaking

Cumanians moved west from the Pontic steppe,

adopted Christianity in 1227, and became Hungari-

an subjects. Mongols attacked again in 1238, and

the rest of the Cumanians fled westward from the

Doniec-Dnieper interfluve. In 1239 they crossed

the Carpathians. According to the 1243–1244 Car-

men miserabile by the Italian chronicler Rogerius

(later archbishop of Split, Croatia), “because of

their great multitude, and because their people were

hard and crude and knew no subordination . . .

[King Béla IV of Hungary] nominated one of his

own leaders to guide them into the center of his

country.” Cumanians were granted freedom but

had to submit to the king and convert to Chris-

tianity.

When Mongols reached Hungary in 1241,

Magyars thought they spotted Cumanians among

the attackers and killed the khan of the new settlers.

Cumanians fled southeast, raping and pillaging on

their way. Around 1246 the king invited Cumanians

back into Hungary. A 1279 decree defined a contig-

uous Cumanian homeland in the central portion of

the Great Hungarian Plain. It prescribed that Cu-

manians take up a “Christian, sedentary” way of life.

Cumanian cavalry, however, remained instrumental

in the royal army until the mid-fourteenth century.

Assimilation was accomplished only by the sixteenth

century, when permanent settlements became com-

mon and Cumanians erected their own churches.

See also Animal Husbandry; Goths between the Baltic

and Black Seas; Huns; Langobards; Ostrogoths;

Scythians; Visigoths (all vol. 2, part 7).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bóna, István. “Die Awarenfeldzüge und der Untergang der

Byzantinischen Provinzen and der unteren Donau.” In

Kontakte zwischen Iran, Byzanz und der Steppe in 6.–7.

jh. Edited by Csanád Bálint, pp. 163–183. Budapest,

Hungary: Varia Archaeologica Hungariae, 2000.

———. “The Hungarians and Europe in the Tenth Centu-

ry.” In A Cultural History of Hungary: From the Begin-

ning to the Eighteenth Century. Edited by L. Kósa, pp.

42–59. Budapest, Hungary: Corvina-Osiris Press,

1999.

———. The Dawn of the Dark Ages: The Gepids and the Lom-

bards in the Carpathian Basin. Budapest, Hungary:

Corvina Press, Hereditas Series, 1976.

Bóna, István, and Margit Nagy. Gepidische Gräberfelder am

Theissgebiet I. Budapest, Hungary: Magyar Nemzeti

Múzeum, 2002.

Christie, Neil. The Lombards. Oxford: Blackwell Press, 1995.

Daim, Falko, ed. Reitervölker aus dem Osten: Hunnen +

Awaren. Schloss Halbturn, Austria: Burgenländische

Landesausstellung, 1996.

Kovács, Tibor, and Éva Garam, eds. A Magyar Nemzeti

Múzeum régészeti kiállításának vezeto˜je (Kr. e.

400,000–Kr. u. 804) [Guide to the archaeological ex-

hibit of the Hungarian National Museum]. Budapest,

Hungary: Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum, 2002.

Laszlovszky, József, ed. Tender Meat under the Saddle: Cus-

toms of Eating, Drinking, and Hospitality among Con-

quering Hungarians and Nomadic Peoples. Krems, Aus-

tria: Medium Aevum Quotidianum, 1998.

Lengyel, Alfonz, and G. T. B. Radan, eds. The Archaeology

of Roman Pannonia. Budapest, Hungary, and Lexing-

ton: University Press of Kentucky/Akadémiai Kiadó,

1980.

Pálóczi Horváth, András. Pechenegs, Cumans, Iasians: Steppe

Peoples in Medieval Hungary. Budapest, Hungary: Cor-

vina Press, Hereditas Series, 1989.

L

ÁSZLÓ BARTOSIEWICZ

HUNGARY

ANCIENT EUROPE

579

EARLY MIDDLE AGES/MIGRATION PERIOD

CZECH LANDS/SLOVAKIA

■

The Slavs may have entered the historical scene late,

but they did so in an impressive way. Sometime in

the fifth century

A.D., the expansion of the nomadic

Huns in central Asia led to massive ethnic migra-

tions. The Slavs, too, began to move away from

their original domiciles in the east of Europe, soon

becoming acquainted with the advanced cultural

world of the eastern Roman Empire. From

A.D. 531

onward, Slavic warriors plundered the territory of

the Balkans, leaving terror in their wake. The Slavic

expansion to central Europe took a quieter course.

There the colonists met only remnants of the origi-

nal Germanic population in an almost depopulated

landscape. At about the beginning of the sixth cen-

tury, the first wave of immigration arrived in the ter-

ritories of Bohemia and Moravia. The chronicler

Kosmas, who lived and worked during the late elev-

enth century and early twelfth century, describes the

time of the arrival of the Slavs (who were led by their

mythical ancestor C

ˇ

ech, or “Czech”) and their set-

tlement as idyllic and their life as quiet and peaceful.

The results of archaeological excavations suggest

that this was the case.

The first Slavic settlements followed the fertile

basins of major rivers, and their appearance is re-

markably uniform: a group of several countersunk

dwellings in plots 3.65 by 3.65 meters in size, all

equipped with oven and bed plus storage pits for

grain. Traces of internal social differentiation are

unclear. Unfortified settlements are laid out in a

more or less regular pattern at a distance of about

1.6 kilometers from one another, which gave the in-

dividual communities space for fields and pastures.

Only occasionally, a grouping of some ten houses

appears at a strategic and important site.

THE EMPIRE OF SAMO

The peaceful times did not last long. Apart from the

influences of states west and south of Czech territo-

ry, social changes in the Slavic world stemmed from

a new wave of attacks, this time by the Avars from

the steppes of Asia. In

A.D. 558 a new series of con-

flicts with the Roman Empire began. The Germanic

Langobards started to leave Pannonia, and the terri-

tory was occupied by the Avar ruler. Thus the Czech

Slavs gained an unwelcome neighbor in the south-

east. The pressure from the incursions of these no-

madic horsemen brought about a new wave of Slav-

ic colonists, who arrived in Bohemia and Moravia at

the end of the sixth century.

The degree of the Slavs’ dependence on the

Avars varied. Some Slavic troops even fought in the

Avar armies, but at the beginning of the seventh

century relations became strained. Led by the mer-

chant Samo, perhaps an emissary of the western

Roman Empire, the Slavs rose up and prevailed

against the Avars. In

A.D. 623 Samo was elected

king of a newly established “state,” which included

modern-day Bohemia and Moravia plus parts of

Slovakia and Carinthia (now a part of Austria).

Samo’s domain probably had its center in the low-

lands of southern Moravia.

The independence of this new empire soon be-

came a thorn in the side of its neighbor in the west,

the Merovingian western Roman Empire. In

A.D.

631 King Dagobert of that empire sent expedition-

580

ANCIENT EUROPE