Ball Martin, M?ller Nicole. The Celtic Languages

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

716 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

have to go to X to fi nd it.’ The generational shift was evident, and one man, about 50,

commented, ‘our generation already spoke French by preference’ (Timm 1983: 453).

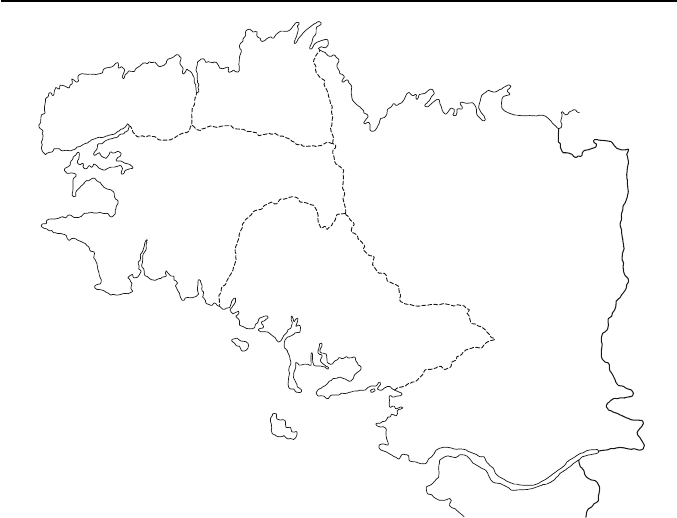

My investigation brought one important modifi cation to the Sébillot/Panier line: the

city of Vannes and its hinterlands in the Morbihan, previously included west of the fron-

tier, needed to be situated east of the line (see Figure 15.1), as interviewees stressed that

Breton was ‘fi nished’ in that area and that ‘one needs to go to the Finistère’ to fi nd it (ibid.:

454). In the end, it was clear that the very concept of a linguistic ‘frontier’ separating

Breton- speaking from French- speaking Brittany was illusory. Instead I envisioned Breton

as ‘surviving in islands strung throughout a widening sea of French speakers’ (ibid.). In

twenty- fi rst- century Brittany, this interpretation still holds, though the islands are becom-

ing smaller and smaller among the traditional Breton- speaking population and may be

better conceptualized as social networks or communities of practice (see below).

BRITTANY’S LATER HISTORY

Current versions of the history of Brittany look to the ‘glorious’ years of an independent

kingdom under Nominoë and then under several male successors who ruled Brittany until

907. However, this independence started unravelling with assaults in that same year by

Vikings who devastated Brittany, burning churches and monasteries, and pillaging as they

went. The raids wreaked havoc on the literary treasures created and housed in monas-

tic establishments. Taking what manuscripts they could, the monks, along with many of

the aristocracy, fl ed to more secure sites well to the east or to England and other parts of

Europe (Galliou and Jones 1991: 167–8).

Though Viking raids on Brittany gradually subsided and a new Breton leader – Alain

Barbetorte (d. 952) – attempted to restore the kingdom, he did not enjoy the success of

his predecessors and Brittany was inexorably drawn politically into the Frankish fold,

bolstered by aristocratic intermarriage between Bretons and Franco- Normans.

6

Brittany

entered the Middle Ages as an emerging feudal society dominated by a landed aristocracy,

some with powerful political links to the Carolingian dynasty and its Capetian succes-

sor. The territory existed as a semi- autonomous duchy through much of the Middle Ages

until it was offi cially annexed to the French Crown in 1532 by an Act of Union. This Act

still resonates negatively with many Bretons who view as humiliating a statue that was

inaugurated in 1911 in Rennes showing the last Duchess of Brittany, Anne de Bretagne,

kneeling in submission to the French king. A clandestine group of Breton nationalists

bombed the statue in 1932 on the occasion of the celebration of the 400th year of the Act

of Union.

In spite of its incorporation into the French Crown in the sixteenth century, Brittany

continued to enjoy a fairly high degree of autonomy, having retained its own parliament

and wielding considerable control over its own fi nances and judicial system; indeed for

several centuries following the union it had a fl ourishing economy, based on agricultural

goods, salt, industrial crops such as fl ax and hemp, and a thriving merchant marine and

fi shing industry (Collins 1994: 60). Galliou and Jones refer to maritime expansion in the

seventeenth–eighteenth century that created ‘the commercial fortunes of the merchants,

privateers, armateurs [ship- owners] and bourgeoisie of the great ports – Nantes, Brest,

Saint- Malo and Port- Louis (now Lorient, M[orbihan])’. These historians point out that

one can still see this wealth in the architecture of Nantes and in many chateaux and large

country houses in the environs (1991: 284). On the other hand, conditions for the masses

in late medieval times ‘would have differed scarcely at all from the penury revealed by the

LANGUAGE, CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN BRITTANY 717

excavations at Lann Gouh en Melrand and Pen- er- Malo [twelfth century] . . . windowless

temporary shacks, sunken- fl oored huts or simple single- cell buildings’ (ibid.: 259–60).

Conditions did not improve signifi cantly among the ordinary people until the latter half of

the nineteenth century.

Travellers through Brittany in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries attest to this back-

wardness, encapsulated in one famous writer’s description – Victor Hugo in Quatre- vingt

treize – of the Breton peasant:

wild, grave and peculiar, this clear- eyed man with long hair, living off of milk and

chestnuts, restricted to his thatched roof . . . using water only for drinking . . . speak-

ing a dead language, loving his kings, his lords, his priests, his lice

(cited in Laîné 1992: 65)

Breton monolingualism was the norm for the very numerous poor peasantry evoked by

Hugo as well as for other subsistence- level social classes well into the nineteenth cen-

tury (cf. Deguignet 1904). All of this began changing in the last decades of that century as

the forces of modernization, urbanization, out- migration, compulsory education and con-

scription drove the process of restructuring Breton society that would play out over the

next 150 years, favouring the learning and use of French and the increasing marginaliza-

tion of the Breton language (see below).

LANGUAGE HISTORY

Old Breton is dated to the fi fth–eleventh centuries. Unfortunately, there is not much evi-

dence of this early form of the language; what exists consists of a few proper nouns for the

earliest centuries and then, from the eighth century, more numerous examples in the form

of glosses on manuscripts and additional personal and place names found in cartularies or

other Latin sources (Fleuriot 1985: 33). However, it is not doubted by most historians that

Old Breton had a rich literary tradition that, for a variety of reasons, including the contin-

uing assaults on Breton monasteries by the Vikings during the ninth to tenth centuries, has

largely disappeared.

Middle Breton runs from the eleventh century to the early seventeenth century. His-

torical linguist Kenneth Jackson breaks this into two sub- periods, the fi rst lasting until

c. 1450 and during which most information surviving about this form of the language is

found in cartularies and other documents (1967: 3). The longest piece of text known to us

from this period is in fragments of a poem penned by a scribe in the margins of a Latin

manuscript

7

that he had been copying; it has been dated to approximately 1350. These are

described by Hardie (1948: 6) as ‘typical boutades humoristiques’, which helped ease the

dreary monotony of scribe- work; they have been reconstructed from the handwriting and

translated by Breton scholars Ernault and Loth as

An guen heguen am louenas The fair one, her cheek gladdened me

An hegarat an lacat glas The lovable (one) of the blue eye

Mar ham guorant va karantic If my dear one assures me [that]

Da vout in nos o he costic I shall be in the night at her side

Vam garet. nep prêt. et ca. va Mother dear, etc.

(Loth 1913: 244–5; 247)

718 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

The internal rhyming scheme, so characteristic of Middle Breton, is very apparent in these

fragments. The last line, with its mention of ‘etc.’, seems to show that it was a well- known

refrain and did not need to be written out (Hardie 1948: 7).

Historian Michael Jones points out that there are no administrative texts in Breton

from this period and that ‘it is rare indeed even to fi nd a phrase recorded in that language’

(2003: 5). He does give one example extracted from an inquiry in the city of Vannes in

the year 1400 following a public disturbance in which a local church authority, writing in

Latin, described how men and women from the bourg began to shout in Breton ‘Ferwet,

ferwet, ferwet, donet avant’, which the clergyman translates (in Latin) as ‘Close up, close

up, close up, they are coming here” (ibid.: 12, n. 47). One cannot fail to notice the French

infl uence surfacing in this fragment of Breton.

The second sub- period of Middle Breton identifi ed by Jackson runs from the latter half

of the fi fteenth century to the early seventeenth. It gives us the richest set of literary texts

(ibid.), including the fi rst printed work in Breton, the Catholicon – a Breton–French–Latin

dictionary compiled by Jean (Jehan) Lagadeuc (1499), though it had appeared much ear-

lier, in 1464, in manuscript form – saints’ lives and other doctrinal writings, as well as

dramatic works of a religious nature.

Modern Breton is dated from the seventeenth century to the present. Here, too, it is

necessary to distinguish two phases. Jackson speaks of Early Modern Breton for the

seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and Modern Breton for the nineteenth and twentieth;

in each case, of course, what we are really talking about is an elaborated, literary Breton,

rather than the traditional spoken forms of the language, which are fairly different in pho-

nology and lexicon. However, the elaborated variety has become in recent decades the

principal form of Breton offered (and available) to people learning it as a second or addi-

tional language, about which more will be presented further on.

Modern (literary) Breton, particularly following its re- vamping in the early decades of

the twentieth century, is associated with a considerable body of literature encompassing

multiple genres, with new titles appearing regularly at present. In this regard it has tran-

scended the fairly limited repertoire of themes and genres associated with Breton- medium

literature of past centuries.

THE PRESENT SITUATION

Numbers and age cohorts of speakers

It has been estimated that in the early years of the twentieth century 1.4 million or 93 per

cent of the population of Lower Brittany was still speaking Breton on a daily basis (Brou-

dic 1983; cited in Foy 2002: 29). This included an estimated 900,000 monolinguals and

500,000 bilinguals (ibid.). It has also been estimated that 100,000 people (7 per cent of

the total population of Lower Brittany: 1.5 million) were at that time monolingual French

speakers (ibid.).

8

A diglossic regime regulating language choice would most likely have

prevailed at that time – i.e., with French as the High language for most public and offi cial

domains of use and with Breton as the Low language for family, neighbourhood, and work

contexts (agricultural, maritime), and for religion (along with Latin and some French).

Fifty years later, in 1952, Francis Gourvil estimated (he did not conduct a survey)

that there were 1.1 million people speaking Breton regularly, but now with only 100,000

of these being monolinguals, the remaining one million being bilinguals. Monolingual

French speakers had risen in numbers to 400,000 or 27 per cent of the population (Gour-

vil 1968: 106–8).

LANGUAGE, CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN BRITTANY 719

Several decades after Gourvil’s estimates, surveys on language use in Brittany were

undertaken by individual researchers, radio stations, and such agencies as the Breton-

regional newspaper Le Télégramme and the research institute TMO- Régions Ouest;

these revealed steady declines and even dramatic drops in the number of people in Lower

Brittany identifying themselves as Breton speakers. For example, Humphrey Lloyd Hum-

phreys in 1962 conducted a survey in the commune of Bothoa in northern Lower Brittany,

which was based in part on the local electoral register of 1882; extrapolating from that,

he derived an estimated 686,000 speakers for the whole of Lower Brittany (1993: 627–8).

In 1987 Fañch Broudic worked with the regional public radio station Radio Bretagne

Ouest to sample 999 Bretons in Finistère, arriving at a projected estimate of 614,587

adults (aged 15 or more) speaking Breton in Lower Brittany, i.e., 57.1 per cent of that

population, with an additional 195,146 who claimed to understand but not speak the lan-

guage (reported in Humphreys 1993: 630).

Ten years later Broudic worked with the TMO- Régions Institute to conduct a new sur-

vey which turned in a dramatic result: the revised estimate for the number of individuals

able to speak Breton was 240,000, less than half the number reported in Broudic (1987).

An additional 140,000 claimed to understand the language. The age distribution of speak-

ers was similarly striking, although not completely surprising in light of clear tendencies

reported on in the literature on this subject in the past (see Table 15.1).

Table 15.1 Distribution of Breton speakers by age in 1997. Source: Broudic 1999: 32

Age Percentage of Breton speakers

15–19 0.5

20–39 5.0

40–59 28.0

60–74 49.5

> 75 17.0

In today’s Brittany there are no longer any Breton monolinguals, as all Breton speakers

also speak French and the vast majority have acquired their literacy skills in that lan-

guage as well (except in the case of children schooled in Diwan or bilingual classes, to be

discussed later). Further, nearly 80 per cent of speakers who know of Breton, according

to Broudic, say they use it only occasionally (1997: 45), even among friends and with

family, the former strongholds of the language.

The most recent survey on speakers of non- French languages in France was conducted

by INSEE in 1999 (results reported in Le Bouëtté 2003; see also Broudic 2003). This is

an important survey, as it is the largest representative sample ever attempted in France:

380,000 adults aged 18 or more were surveyed throughout the country, including 40,000

in Brittany. The principal fi nding relevant to the present overview is that 257,000 Breton

adults claimed that they sometimes used Breton to converse with people close to them

(spouses, partners, parents, friends, colleagues, shopkeepers, etc.); interestingly, English

was second, with 111,600 claiming to speak the latter at times in these situations. Not sur-

prisingly, the survey also showed that the use of Breton was ten times more likely in the

western department of Finistère than in the eastern department of Ile- et- Vilaine. Another

fi nding – one known anecdotally for quite a while, but here confi rmed – was this: in the

1920s 60 per cent of children learned their Breton from their parents; by the 1980s, only

6 per cent of children learned Breton in this old- fashioned way (ibid.: 21). To anticipate

a bit, by the 1980s Diwan’s immersion pedagogy was gaining headway, and the public

720 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

school and Catholic school systems would soon follow this lead with the introduction of

bilingual (Breton–French) classes. It is in these institutions that the vast majority of chil-

dren from the 1980s on would learn their Breton.

REASONS FOR THE DECLINE IN THE USE OF BRETON

For several decades scholars have been analysing the reasons for the decline in the use

of Breton (and other regional languages in France and other parts of Europe). There are

doubtless many features shared in the stories of regional languages. In the case of such

languages in France, these reasons may be considered under two rubrics: (1) social, eco-

nomic, institutional and lifestyle changes that affected the entire country; (2) negative

attitudes towards regional languages.

Socioeconomic, institutional and lifestyle changes

A good example of institutional change that had widespread consequences for Breton is

found in the educational reforms carried out by Jules Ferry, the Minister of Education

in the 1880s. Ferry’s ‘laws’ established free, public, compulsory, and secular elementary

education for all children of primary school age, and were thus an important vector of lin-

guistic change, bringing the standard, offi cial language of the Republic into their lives,

and serving as the basis for the development of their literacy and numeracy skills.

Other forces of a socioeconomic nature were also at work that would have a cumula-

tive impact on linguistic practices. The export of commercial products and the attraction

of foreign business people to Brittany encouraged the diffusion of French among at least

the commercial classes of Bretons. Commercial exchanges with outsiders had in fact been

going on for some time, for even during the sixteenth–seventeenth centuries Brittany was

recognized as a centre of fi rst- class horse fairs, drawing customers from as far away as

Germany and the Netherlands (Collins 1994: 60); French was necessarily the language

of such negotiations. In the nineteenth century, the laying of national rail lines that linked

much of inland Brittany with the outside facilitated and accelerated such exchanges and

provided greater accessibility to the more isolated interior areas of the peninsula. The rail-

way also facilitated out- migration of Bretons to other sites in France in search of work,

especially to the Paris region, where it was necessary for them to learn at least some

French. In fact, Paris had for centuries been a favoured destination of Bretons seeking to

improve their economic lot, and we fi nd that as early as the thirteenth century there was

a satirical literature caricaturing the Bretons as menial laborers and poking fun at their

awkward French (Galliou and Jones 1991: 185). Construction of railways also brought

French- speaking railway workers into Brittany, along with their often more left- leaning

political ideas, as happened in the interior largely bretonnant town of Carhaix in the early

twentieth century (Broudic 1995: 414, n. 8). An evolution in mentalités was well under

way: Breton was increasingly viewed as the language of socioeconomic stagnation and

the past, French as the language of social mobility, high culture and the future. Unsur-

prisingly, parents began choosing in ever- increasing numbers, especially after the Second

World War, not to “burden” their own children with the ancestral tongue (see below).

Universal male conscription was instituted in 1872, which meant that young Breton

men serving in the French armed services would be exposed to and would almost cer-

tainly learn some French, although they may have continued speaking Breton among

themselves. There are accounts of especially harsh verbal treatment of Breton recruits by

LANGUAGE, CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN BRITTANY 721

French- speaking offi cers and soldiers, scathing and racist in tone; and it is claimed that

some Breton soldiers were summarily executed as German spies during the First World

War because they did not speak French and could not defend themselves in that language

against espionage charges (Gwegen 1975: 45).

Finally, an important lifestyle change in the form of tourism became a reality for the

more leisured classes beginning in the mid- to late nineteenth century, and Brittany was a

destination of choice for Parisian tourists (and also for artists such as Gauguin). A hostelry

industry expanded to accommodate such visitors, whose numbers swelled following the

French state’s institution in 1936 of paid hodiays for all salaried workers. Naturally this

would have promoted the learning of French among locals working or seeking work in the

booming hotel and restaurant industry.

Negative attitudes towards the language

In addition to the effects of universal French- based education, military conscription, and

socioeconomic developments on the practice and maintenance of (or shift from) Breton,

the complex issue of internalized negative attitudes towards the language, and sources

of these, cannot be overlooked. Though not affecting everyone everywhere in Brittany,

the use of le symbole introduced during the Third Republic to humiliate school children

‘caught’ speaking Breton on the school premises produced in many who experienced it a

negative attitude towards their mother tongue, which of course was the intended effect.

Le symbole (‘the symbol’, variably called le signal ‘the signal’, le signe ‘the sign’, or

la vache ‘the cow’) worked in this way: a simple object from daily life – most often a

sabot (the iconic peasant wooden shoe), but sometimes a piece of wood, a bobbin, an old

potato, a cork, an iron ring, a tin can, etc. (Prémel 1995: 85–6) – would be attached by the

teacher around the neck of a child heard speaking Breton; the only way the child could

earn release from this humiliating display was by reporting hearing another child speak-

ing Breton, to whom the ‘symbol’ would then be transferred, and so the item passed from

one child to another as the day progressed. The child ending up with it at the end of the

day might receive corporal punishment, be assigned to clean the latrines after school;

or perhaps be made to write 100 times on the chalkboard such lines as Je parle breton à

l’école ‘I speak Breton at school’ (ibid.: 81). For many children who experienced this sort

of treatment, Breton would become negatively associated with school, learning, and most

aspects of social mobility, hastening the shift to French.

Parents often approved of this practice, for they saw it clearly in their children’s best

interests to learn French, by whatever means necessary, knowing that in speaking only

Breton they would be on a short tether vis- à- vis the expanding outside world. However,

this did not mean that Breton would not continue to be the principal, or sole, language of

the household and the neighbourhood in rural Brittany, and thus many children from this

period (late 1800s–early 1900s) would still have spoken the language, or at the least, have

developed a strong passive or comprehension knowledge of it.

Complementing the negative set of values attached to speaking Breton was the

increasing perception of French as the language not only of education and upward socio-

economic mobility but of fashionability, of being in vogue, a perception held especially

by the female population. Linguist Albert Dauzat (1929) reported that in the 1920s young

rural women from Lower Brittany dreamed not of marrying an eligible peasant bachelor

of their own pays, but rather of walking away on the arm of a civil servant or a military

man, and setting up house in the nearby bourg or town. He also notes how young female

servants in hotels would pretend not to know a word of Breton in exchanges with clients

722 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

dressed in city attire (Dauzat 1929: 38). Fañch Broudic briefl y discusses a 1951 study

that considered gender differences in the use of Breton at that time; of young women the

study’s author says, ‘Every time a girl has been relatively distanced from her parents, she

only speaks French to old people and even . . . to the cows’ (1995: 428).

In the early 1970s, sociologist Fañch Elegoët conducted interviews with fi fty-nine Bre-

tons living in Northern Finistère, fi nding that while the vast majority of the men (30/34)

agreed to hold the interview with him in Breton, less than half (9/19) of the women agreed

to do so. Moreover, while all the men 17–20 years old would speak Breton in their neigh-

bourhood – at least with older people – young women of that age would never do so

(reported in Gwegen 1975: 62). In a multi- year study of social change conducted by a

team of social scientists in the community of Plodémet (Finistère) in the early 1960s,

one researcher concluded that ‘women [are] the secret agent of modernity’ (Morin 1967:

164).

During the Second World War, the German occupation of France, and the subsequent

unfortunate choice made by a small number of Breton militants belonging to the Parti

National Breton (PNB) to collaborate with the Nazis in the hope of ultimately securing

Breton independence, the Breton language was further undermined. The PNB’s offi cial

organ, Breiz Atao (Brittany Forever) has become emblematic of this entire movement,

and the mere mention of it today can be moderately distressing to many Bretons.

As part of the aftermath of that war, Breton cultural expression was largely repressed

for some years as thousands of Bretons were prosecuted by the French government under

suspicion of collaboration even in the absence of direct evidence of this (Fouéré 1977: 67;

Hamon 2001: 229). Several of the most prominent leaders of the Nazi- implicated activists

were condemned to death or sent to forced labor camps (Fouéré 1977: 67–8); others were

exiled from France. It is important to point out that the vast majority of Bretons during

this diffi cult period took no part in this separatist movement and, indeed, were outspoken

French patriots; many were among the Resistance fi ghters opposing both the Nazis and

Petain’s Vichy Regime.

9

However, the taint of ‘collabo’ came subsequently to be associ-

ated with anything faintly resembling Breton political organization, more so than in other

regions of France, which also had had collaborators in their midst (ibid.)

THE RE- VALORIZATION OF BRETON LANGUAGE AND CULTURE

In the late 1940s certain elements of Breton culture began to re- emerge more publicly

again: L’Association des sonneurs de biniou (The Association of Biniou Players) was

reorganized in 1946; in the same year the Breton language literary revue Al Liamm was

launched (Fouéré 1977: 75), and continues to this day. The national Loi Deixonne (Deix-

onne Law) was passed in 1951, making it possible for regional languages to be taught

optionally for a few hours a week under certain circumstances; it was in truth not a very

meaningful advance for teaching or learning such languages, given the conditions it

imposed, but it was at least a nod in the direction of tolerance of (a tightly constrained)

linguistic diversity. On the other hand, courses by correspondence (which had been

started before the Second World War) continued, as well as Breton language workshops

and summer camps (ibid.: 78).

Also re- emerging after the Second World War in Brittany were Cercles celtiques

(Celtic Circles), volunteer/enthusiast associations, focusing on the promotion of tradi-

tional songs and dances throughout historic Brittany. Public performance of dances in

traditional costumes is one of the goals of these circles, and they have become a familiar

LANGUAGE, CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN BRITTANY 723

part of the lavish festivals, found especially in the summertime in Brittany. More local

festivals known as festoù- noz (night festivals) based on traditional communal parties con-

sisting of singing kan- ha- diskan (call- and- response) and group dancing, were re- instituted

in the late 1950s and have recently become very popular in their own right, for younger

generations as well.

Brittany’s linguistic and cultural renewal was accelerated by the tumultuous events of

1968 that shook France and much of the rest of western Europe, launching a new era of

movements to revitalize languishing ethnolinguistic minorities and to gain more local or

regional control of social and economic institutions. Along with other regions in France,

Brittany was swept into this new momentum. Two major strikes by workers in Brittany

in 1972 (factory workers in St Brieuc and milk producers in central Brittany) helped

draw general public attention to issues of inequity felt by the regions vis- à- vis the cen-

tral authorities, and a growing current of sentiment against centralized government was

becoming discernible among other sectors of the Breton population than those centrally

involved in the strikes. The metaphor of Brittany as an ‘internal colony’, around since the

early 1960s (Fouéré 1977: 87), with France (or at least Paris) as the occupying power of a

‘colonized’ Brittany, was gaining greater and greater currency.

It is during this period of foment, in the late 1960s through the 1970s, that the seeds

were sown of a vigorous revalorization of the Breton language, now seen by much of the

public as a distinctive symbol of Breton identity. There was an upsurge in the production of

Breton learners’ manuals and cassette tape sets; new editions of older dictionaries appeared

along with the publication of new ones. Increasing numbers of summer and weekend lan-

guage camps were organized, reaching out to adults to learn the traditional language. A

signal event during this era was the creation in 1977 of a Breton- medium nursery school,

the fi rst of the Diwan classes that would soon proliferate in Brittany (see below).

In sum, the decades following the Second World War, particularly from the 1960s to

the present, have brought an increasing recognition and validation of both Breton lan-

guage and culture. At the same time the traditional Breton- speaking culture has been

disappearing through the effects of modernization, urbanization, globalization, and of

course the inevitable attrition due to the aging of the population who are the last standard-

bearers of that traditional culture.

FORMS OF BRETON

The Breton language has thus far been discussed in rather generic terms, but this masks

considerable underlying complexities that must be addressed in any account of the socio-

linguistic situation in Brittany. This section provides an overview of the varieties of

Breton, of efforts to normalize the language through time and of the latter- day construc-

tion of what is now usually called ‘Neo- Breton’ in the literature.

Regional dialects: the vernaculars

It has long been customary, if not entirely justifi able linguistically, to speak of four

regional dialects of (spoken) Breton that correspond territorially, grosso modo, to the four

ancient dioceses of medieval Brittany: to the north lies the diocese of Léon, whence the

dialect designator léonais (in French, leoneg in Breton); east of that lies Tréger and its

vernacular Breton trégorrois (Breton tregerieg); the central diocese is called Cornouaille,

with its dialect cornouaillais (Breton kerneveg); and in the southern part of the peninsula

724 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

is found the diocese of Vannes and its dialect vannetais (Breton gwenedeg, see Figure

15.2). Together the three northern dialects are often abbreviated as KLT. Vannetais, as

noted earlier, differs suffi ciently from the other three, principally in terms of phonology,

10

to have retained its own orthography, in spite of twentieth- century efforts to provide a

‘unifi ed’ orthographic representation of the language.

Within each of the traditionally designated regional dialects there is considerable var-

iation at the spoken level, even from commune to commune. This has led one linguist

(Le Dû 1997) to envisage spoken Breton in another way – as consisting of what he calls

‘badumes’ (coined by him from the Breton phrase e- barzh du- mañ, translatable as ‘over

here among us’ (ibid.: 420), that is, highly localized forms of speech among people who

are in daily contact with one another.

In more recent sociolinguistic parlance, we might think of these as the speech forms of

a social network (cf. Milroy 1987) or a community of practice (cf. Eckert and McConnell-

Ginet 1992) and therefore rather different from what is normally understood as a regional

dialect. In any event, the sense of tight connection between a particular place/people and

a particular variety of Breton has been one of the reasons traditional speakers of the lan-

guage have found it awkward, or even bizarre, to speak Breton with others outside their

community of practice, typically preferring to switch to French.

Written forms of the language in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries

Throughout most of the period of Middle Breton, until the fi fteenth century, there was

a more or less shared, interdialect, written form of the language (Abalain 1989: 197).

Léonais/Leoneg

Trégorrois/

Tregerieg

Cornouaillais/

Kerneveg

Vannetais/

Gwenedeg

UPPER BRITTANY

(Romance-speaking)

Figure 15.2 Upper and Lower Brittany and traditional dialect areas within the latter

LANGUAGE, CULTURE AND IDENTITY IN BRITTANY 725

More dialect- slanted writing began to appear after that, probably due to a generalized

teaching of the language, meaning that those writing – often clerics working within their

local jurisdictions producing documents that they hoped would be understood by their

parishioners – improvised as they went along. It was not until the advent of Jean- François

Le Gonidec (1775–1838), generally regarded as the fi rst great grammarian of Breton

– he systematized the language in his Grammaire Celto- bretonne in 1807 – that a seri-

ous attempt to normalize the grammar and its written expression was made. Le Gonidec

made the decision to base this normalized language on the léonais dialect in the north;

in his manipulations he did not attempt to capture vannetais, which had had its own lit-

erary form since the seventeenth century. As Elmar Ternes has pointed out, léonais and

vannetais represent the two most divergent dialects of the four, making the two literary

forms of the language nearly incomprehensible to the majority of Breton speakers (1992:

382). A major emphasis of Le Gonidec was the elimination of French- derived words, to

be replaced with neologisms based on Celtic elements; in fact, this had already been a

concern to some of his predecessors, notably Dom Michel Le Nobletz (1577–1652) in

the sixteenth century, and his disciple Julien Maunoir (1606–1683) in the following cen-

tury. These Jesuit priests were interested in rectifying the French- infused Breton of their

predecessors and contemporaries, whose Breton has long been deprecated as ‘priests’

Breton’ (brezoneg beleg) and compared, in unfl attering terms, with ‘kitchen Latin’ (Timm

1996: 27).

Twentieth- century reforms

The push for lexical purity remained a theme and a modus operandi of subsequent gener-

ations of Breton language reformers, notably in the Grande dictionnaire français–breton

(1980; orig. 1931) of François Vallée (1860–1949) who ‘applied himself to the system-

atic exploitation of the derivational possibilities of Breton for the creation of neologisms’

(Humphreys 1993: 617). Vallée collaborated in his efforts with René Leroux (alias Meven

Mordiern, 1878–1949) to construct a language in which any subject of erudition could be

discussed. Interestingly, neither of these reformers was a native Breton speaker, and they

made little or no effort to come into contact with native speakers of the language (Le Dû

1997: 424), but devoted their lives to perfecting Breton as they understood that process.

Following two generations later in that same spirit of linguistic reform was a group of

writers and activists gathered under the umbrella of a new literary journal called Gwalarn,

headed by the Brest- born (hence native francophone) linguist and English teacher Roparz

Hemon (1905–1974).

In order to promote the teaching of Breton in schools during the Vichy regime, these

language activists decided in 1941 to adopt a completely unifi ed (Breton peurunvan)

orthography that would accommodate certain pronunciation needs of the KLT dialects

and the more divergent vannetais. The result was the incorporation of a new letter, the

digraph <zh>,

11

to be used in words in which the KLT dialects had a written <z> (either

a phonetic [z] or [s] depending on position in the word) and vannetais had a written <h>,

phonetically [h]; thus, for example, Breiz (Brittany) in KLT and Breih in vannetais would

now be written Breizh, and readers would pronounce the letter according to their dialect

preference. The new orthography was soon dubbed in Breton zedacheg (in reference to

the letter <z> (‘zed’) in the digraph). As this reform was made during the time of German

occupation of northern France and the aforementioned collaboration with the occupying

regime on the part of a number of Breton militants and intellectuals, the new orthogra-

phy was soon seen as ideologically tainted in the eyes of many other Bretons and rejected