Ball Martin, M?ller Nicole. The Celtic Languages

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

696 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

did not even know of their existence. Further, such leafl ets and forms were not always

publicly displayed. This meant that if one wanted to use the Welsh language in an offi cial

capacity it entailed the extra effort of seeking out such a facility if it existed.

29

During the late 1980s a number of incremental reforms in education, public administra-

tion, the legal system and local government sought to increase the opportunities available

both to learn and to use Welsh in society. At the time these were recognized as being piece-

meal, insuffi cient and rudimentary. Nevertheless they have had an impact on subsequent

events – none more so than the Education Reform Act, 1988 which granted a Core Subject

status for Welsh in all schools within the statutory education age range of 5–16. For the fi rst

time in national history, all of the children of Wales have had an opportunity to develop

some bilingual skills, and for a substantial minority to develop real fl uency in Welsh. The

most tangible move was the decision taken in July 1988 by the Rt Hon. Peter Walker MP,

acting on the advice of eight prominent Welshmen, to establish the Welsh Language Board.

Its brief was to advise on matters which called for legislative or administrative action. It

was also to advise the Secretary of State for Wales on the use and promotion of the Welsh

language. In January 1989 the Board published Yr Iaith Gymraeg: Strategaeth i’r Dyfodol

(The Welsh Language: A Strategy for the Future) (Welsh Language Board 1989a). Its aims

were to create a bilingual community and to encourage new situations where Welsh could

and would be used. It would seek legislation in order to achieve these aims, but this would

be done within a framework of equal validity rather than of equal status. The Board saw

this as the only way forward and in spite of a discordant response to its proposals, it pre-

sented its case for equal validity to the Secretary of State for Wales in July 1989 and in

October of the same year, it presented a Draft Bill (Welsh Language Board 1989b) to the

Welsh Offi ce. The Board’s approach is that of persuasion and since 1988 it has sought to

expand the use of Welsh in the public sector and more recently in the private sector through

exhortation rather than through compulsion. During 1989 it published A Bilingual Policy:

Guidelines for the Public Sector (Welsh Language Board 1989d) and Practical Options for

the Use of Welsh in Business (Welsh Language Board 1989e). In March 1990 the Inland

Revenue established a special unit for dealing with taxation matters through the medium

of Welsh. The Department of Social Security also developed bilingual policy guidelines

for its staff, and similar initiatives were launched by other state bodies and agencies which

served the general population.

Critics of the Draft Bill agreed with the general aims of the Welsh Language Board, but

feared that it would be too weak to secure permanent success. It advocated equal valid-

ity and not equal status and in this respect followed the lead of the Hughes Parry report

and the Welsh Language Act 1967. Yet the latter did not work satisfactorily. Hughes Parry

(Welsh Offi ce 1965) and the Council for the Welsh Language (1978a) rejected statutory

bilingualism because of serious fi nancial and practical obstacles, in spite of the fact that

such a pattern would have lifted all limitations upon the use of the Welsh language. In

the context of equal validity, the clause which has caused most dissent is 2.la. ‘So far

as is practicable, comply with the reasonable requirements of every person resident in

Wales who indicates that he wishes to receive written material of whatever nature, or

otherwise to communicate, by any means whatsoever in Welsh or English as the case

may be’ (Welsh Language Board 1990b: 2.1a). This may be interpreted as stating that

Welsh is only available if the request is a reasonable one and fulfi lling it is practicable.

The terms ‘reasonable’ and ‘practicable’ may be interpreted in a host of different ways.

Here lies the fear of all who criticized the Draft Bill. Eleri Carrog of ‘Cefn’,

30

reacting to a

revised version of the Draft Bill, said ‘Our basic standpoint is that no individual nor soci-

ety should be forced to prove the reasonableness of using his own language in his own

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 697

country’ (Carrog 1990: 5–6). The revised version stressed that if a request is refused, then

such action would have to be justifi ed at law. The second part of the Bill sought to set up a

Statutory Welsh Language Board which would be responsible for all matters dealing with

language maintenance and possibly with language planning. The need of a single body

to assess and promote linguistic matters was abundantly clear, but there were fears that it

would not be a strong body with the necessary authority to implement policies.

The resultant Welsh Language Act 1993 provided a statutory framework for the treat-

ment of English and Welsh on the basis of equality.

31

Its chief policy instrument was

the strengthened Welsh Language Board, established on 21 December 1993, as a non-

departmental statutory organization.

32

It had three main duties:

1 Advising organizations which were preparing language schemes on the mechanism

of operating the central principle of the Act, that the Welsh and English languages

should be treated on a basis of equality.

2 Advising those who provide services to the public in Wales on issues relevant to the

Welsh language.

3 Advising central government on issues relating to the Welsh language.

The eleven Board members were appointed by the Secretary of State for Wales and they

devoted two days a month to the activities of this quango. The day to day work of the

Board was undertaken by thirty staff members divided into seven areas of responsibil-

ity, namely Policy, Public and Voluntary Sector, Grants and Private Sector, Education and

Training, Marketing and Communication, Finance, Administration.

The Welsh Language Act 1993 details key steps to be taken by the Welsh Language

Board and by public sector bodies in the preparation of Welsh- language schemes. These

schemes are designed to implement the central principle of the act which is to treat Welsh

and English on the basis of equality. Between 1995 and 1999 a total of sixty- seven lan-

guage schemes had been approved including all twenty- two local authorities. On the eve of

devolution notices had been issued to a further fi fty- nine bodies to prepare schemes. Today

over 500 such schemes have been implemented, and undoubtedly they have been highly

instrumental in changing the character of bilingual services within public authorities. Yet

it may be asked how effective they have been in changing the linguistic choice and behav-

iour both of providers and of the general public. Systematic monitoring of the schemes by

the Language Board as part of its audit function reveals a wide variation in behaviour pat-

terns, both among the various local authorities and institutions and by the general public.

33

The Board also had the right to extend its remit in other sectors covered by the Act, and

had given priority to education and training. By June 1998 the Welsh education schemes

of two local authorities had been approved and a further fi fteen were being developed

(Welsh Language Board 1998). Further and higher education colleges, together with

Welsh- medium pre- school provision have also received attention. Between 1998 and

2006 Education Learning Wales (ELWa), with input from the Board, had co- ordinated

a national strategy for Welsh for Adults, and this sector has benefi ted from a more robust

and systematic provision of service, accreditation of Adult Tutors, resource develop-

ment and strategic intervention related to skills acquisition in key areas of the economy,

such as insurance and banking, retails sales and the legal profession. In total, grants of

£2,027,000 were distributed in the year 1997–8 to local authorities to promote Welsh-

language education.

The Welsh Language Board’s primary goal is to enable the language to become self-

sustaining and secure as a medium of communication in Wales. It has set itself four

698 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

priorities: 1) to increase the numbers of Welsh speakers; 2) to provide more opportuni-

ties to use the language; 3) to change the habits of language use and encourage people to

take advantage of the opportunities provided, and 4) to strengthen Welsh as a community

language.

In order to meet its fi rst aim of increasing the numbers speaking Welsh it has focused

its efforts on promoting the use of Welsh among young people by seeking to

• ensure that the provision of Welsh- language and Welsh- medium education and train-

ing is planned in conjunction with the key players, to ensure an appropriate level of

provision for young people to obtain Welsh language education services;

• discuss and formulate policies and effective initiatives for promoting the use of

Welsh among young people, in conjunction with relevant organizations;

• ensure the proper provision of public and voluntary services for young people

through the medium of Welsh (in conjunction with public and voluntary bodies);

• provide grants for initiatives which promote the use of Welsh among young people.

The Board’s second objective is

to agree measures which provide opportunities for the public to use the Welsh lan-

guage with organizations which deal with the public in Wales, giving priority to those

organizations which have contact with a signifi cant number of Welsh speakers, pro-

vide services which are likely to be in greatest demand through the medium of Welsh

or have a high public profi le in Wales, or are infl uential by virtue of their status or

responsibilities.

In order to increase opportunities the Board has

• agreed Welsh language schemes with organizations in accordance with the stated

objective;

• encouraged providers of public services to regard the provision of high- quality

Welsh- medium services on a basis of equality with English as a natural part of pro-

viding services in Wales;

• encouraged Welsh speakers through marketing initiatives to make greater use of the

services available through the medium of Welsh;

• worked closely with the voluntary sector in formulating and implementing Welsh-

language policies, particularly in relation to the delivery of child- or youth- related

services and special needs;

• promoted and facilitated the use of the language in every aspect of education and

training and ensured that appropriate provision is made for persons who wish to learn

Welsh;

• maintained an overview of the strategic educational plans and schemes of all edu-

cation authorities and establishments, and created partnership with the agencies

concerned to improve provision where appropriate;

• ensured that planning of provision for vocational education and training takes

account of potential increases in demand from employers for Welsh speakers;

• promoted the authorization and standardization of Welsh- language terminology, in

conjunction with relevant academic and professional bodies;

• encouraged professional training and recognized standards for translators working

with Welsh;

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 699

• ensured that appropriate Welsh- language software continues to be developed to meet

the needs of users;

• encouraged the increased provision of Welsh in the private sector.

A third objective is to change the habits of language use and encourage people to take

advantage of the opportunities provided. This is done through an innovative marketing

campaign, including attractive bilingual public display signs, the development of a Welsh

spellchecker and on- line dictionary, a direct Welsh Link Line for queries regarding the

Welsh language and language- related services, a language in the workplace portfolio/fi le,

a Plain Welsh campaign with excellent guidelines for writing Welsh, an agreement with

Microsoft that a Welsh version of its computer functions be available from 2005 onwards,

and other improvements to the infrastructure so necessary before a real language choice

can be made by the general public.

The Welsh Language Board’s (WLB) fourth objective is ‘that Welsh- speaking commu-

nities be given the facilities, opportunities and the encouragement needed to maintain and

extend the use of Welsh in those communities’. The Board has committed itself to

• undertake research into the linguistic make- up of Welsh- speaking communities and

the social and economic factors which affect them;

• identify the main threats to the Welsh language within Welsh- speaking communities,

and formulate effective action plans for addressing potential problems in conjunction

with key players across all sectors;

• discuss and develop with unitary authorities, especially those in the traditional strong-

holds, their role in terms of administering language initiatives and co- ordinating

language policies;

• promote co- operation between communities to foster mutual support, encouragement

and understanding;

• assess the effectiveness of existing community- based initiatives (such as ‘Mentrau

Iaith’) as a means of promoting the use of Welsh and their usefulness as a model for

facilitating the creation of new locally run initiatives;

• facilitate the establishment of local language fora to promote Welsh language initia-

tives, to create opportunities for using Welsh and to motivate end encourage people

to do so;

• promote the learning of Welsh by adults (including the provision of worthwhile

opportunities to use Welsh outside the classroom and other ancillary support);

• provide grants to support activities to strengthen Welsh within the community.

A signifi cant infl uence on the ability of Welsh speakers to use their language within

employment is the spread of multilingual Information Technology. Many small companies

have been engaged in this process for a long time, but real co- ordination of develop-

ments in the fi eld was achieved as a result of the Welsh Language Board taking the lead

and advancing strategic initiatives.

34

A priority was the standardization of terminology

and lexicographical resources, which was facilitated by the establishment of a Corpus

Planning Unit within the WLB, whose standardized dictionary of IT terms has proved

invaluable, as have the more universal spellcheckers, grammar checkers and computer-

ized dictionaries, developed in partnership with the WLB.

35

A number of long- standing

issues were tackled by the WLB, whose professional staff have both identifi ed the needs

and resourced the resultant solutions. Among these may be listed: localization and other

applications, switchability of interface and language attributes, especially in relation to

700 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

Microsoft products, KDE and GNOME, bilingual web design standards, and content cre-

ation aids. A key development has been the standardization of Welsh- language keyboards,

diacritical marks and fonts, so that both keyboard short cuts or character code numbers

can be employed by PC users.

36

Another fi eld which has grown as a result of simultaneous developments within IT

and increased demand from the National Assembly for Wales (NAfW), local govern-

ment and major institutions, has been computer-aided translation which although in its

early stages of deployment, augurs well for the greater deployment of bilingual technol-

ogy aids. Speech recognition, adaptive technology and integration of machine translation

and speech technology (MT, SR, TTS) have also developed. However, as any behavioural

scientist will advise, a major stumbling block is the willingness of the end users to take

advantage of the opportunities afforded. Thus basic IT skills training, language awareness

and e- learning are now on the agenda of many specialist training companies.

37

The pre- existent Welsh Offi ce governmental system, though strong in parts, was

more concerned with implementing statutory provision, than with language planning

and the creation of a new vision for bilingualism in Wales. It discharged its remit prima-

rily through the Welsh Language Board, a quango, established by the UK Conservative

government in 1989, to act as a sounding board for the development of Welsh- medium

services. By 1999, the WLB had established itself as the principal agency for the promo-

tion of Welsh in public life. However, throughout the period independent commentators

had queried the original settlement of the Language Act and had concluded that in vest-

ing public institutions with language obligations while gliding over the issue of individual

language rights, the Welsh Language Act had fallen far short of establishing Welsh as a

co- equal language (C. H. Williams 1998a, 2000).

THE IMPACT OF DEVOLUTION ON THE FORMULATION OF LANGUAGE

POLICY, 1999–2008

As a consequence of UK devolution, a Scottish Parliament and a National Assembly for

Wales were established in 1999. The bilingual National Assembly puts into oper ative

effect the reality of two offi cial languages as acknowledged in the Welsh Language Act

of 1993. A priority for the Assembly’s fi rst term was a thorough review of the condition

of Welsh carried out by both the Culture Committee and the Education Committee. The

key recommendation was the political goal of establishing a bilingual society to be en-

couraged by the implementation of a new government strategy as enunciated in Iaith

Pawb (2003). Critical decisions on language policy are now being taken by involved

and informed politicians, leading many to presume that civil society has also been ‘em-

powered’ by devolution in respect of formulating and implementing language- related

policies.

38

The largely positive trends identifi ed by the 2001 census on the Welsh language

also boosted self- confi dence as a 2 per cent increase in the proportion of Welsh speakers

was recorded between 1991 and 2001. These results need to be tempered by the type of

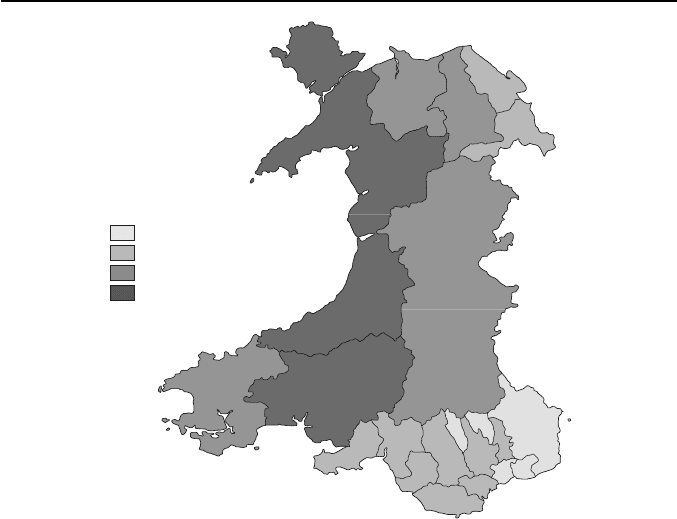

critical analysis offered by Higgs et al. (2004). As Figure 14.10 reveals, the overall pattern

from the censuses of 1981 and 1991 is retained with only Angelsey, Gwynedd, Ceredigion

and Carmarthenshire having over 50 per cent of their population who can speak Welsh. In

terms of absolute numbers, Carmarthenshire has the largest numbers of Welsh speakers.

Following a comprehensive review of the state of Welsh undertaken during 2002, the

WAG has committed itself to achieving these fi ve goals:

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 701

1 by 2011 to increase the proportion of Welsh speakers by 5 percentage points from the

2001 census baseline;

2 to arrest the decline in heartland communities, especially those with close to 70 per

cent+ Welsh speakers;

3 to increase the proportion of children in pre- school Welsh education;

4 to increase the proportion of families where Welsh is the principal language;

5 to increase the provision of Welsh- medium services in the public, private and volun-

tary sectors.

Iaith Pawb is the current benchmark for calibrating government commitment. It has

adopted many of the fi ne recommendations put to the Assembly’s Education and Cul-

ture reviews during 2002. The most notable of these are: the operation of the principle of

language equality; devising an effective in- house bilingual culture; deciding how Welsh

will be a crosscutting issue in all aspects of policy; producing bilingual legislation; devel-

oping a professional bilingual legislative drafting team of jurilinguists as in Canada;

developing innovative IT translation procedures; prioritizing the NAfW’s translation needs;

fi nessing WAG’s relationship with the Welsh Language Board and its many partners; relat-

ing its bilingual practices to other levels of government, institutions and to civil society.

A critical area of sociolinguistic maintenance is language transmission both within the

family and within the education system. Thus a campaign has been launched to boost lan-

guage acquisition, principally through the statutory age 5–16 education provision, life- long

learning, and latecomer centres. In an increasingly mixed language of marriage context the

Percentages

0–10

10–20

20–50

50–70

Figure 14.10 Proportion of people aged 3 and over who can speak Welsh (2001 census)

Source: Offi ce of National Statistics (2003); reproduced from Higgs et al. 2004: 192

702 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

successful pilot project on the ‘Twf’ – Family Language Transfer – programme will be

extended to other sites in Wales. There is a commitment to boosting the bilingual services

of NHS Wales, and of Iaith Gwaith, the Welsh in the workplace programme. Finally, in

order to access such increased choice, the government has recognized the need to invest in

language tools and the sociocultural infrastructure both through increasing the resources

of the WLB and through its own in- house developments. The WAG has to determine how

it will handle the recommendations adopted by Iaith Pawb, listed earlier in the pargraph.

Beyond the realms of public administration there remains the pressing need to promote

Welsh within the private sector. This would include greater political and legal encourage-

ment, with sanctions where necessary, the adoption of holistic perspectives rather than

a fragmented and sectoral mind- set; the development of appropriate terminology and

sharing of best practice; a Language Standardization Centre; the highlighting of the eco-

nomic benefi ts of bilingualism; encouraging a professional discussion regarding the role

of Welsh in the economy; developing role models among the SMEs and larger companies;

infl uencing key decision- makers who are often based outside Wales. Whether a single

new Welsh Language Act can deliver such a diverse range of responses is problematic,

but there can be no doubt that the absence of binding legislation affecting the bilingual

delivery of goods and services from whatever source is the greatest impediment to the

realization of a fully functional bilingual society.

For the immediate future a number of reforms are required. These would include:

• a review of the way in which Welsh is taught and used as a medium for other subjects

within the statutory education sector;

• a comprehensive review of teacher training for Welsh medium and bilingual schools;

• priority action in the designated ‘Fro Gymraeg’ districts;

39

• more concerted action by the WDA, WLB, WTB, and ELWa (and their successor

agencies) to implement the integrated planning and policy proposals agreed within

the Language and Economy Discussion Group;

• urgent consideration to the need to expand the bilingual education and training oppor-

tunities afforded by the Welsh university and further education sector;

• extension of the Welsh Language Act, both to strengthen the status of Welsh within a

revised political landscape and to take account of the rights of consumers and work-

ers within designated parts of the private sector;

• the establishment of a Language Commissioner for Wales.

40

COALITION GOVERNMENT FOR ONE WALES

In the summer of 2007 the Labour Party and Plaid formed a coalition government, based

on the agreed policy aims enunciated in ‘One Wales’ (2007). The coalition government

allowed Plaid to enter government with three strategic areas of responsibility. Its leader

Ieuan Wyn Jones became the Economy and Transport Minister, Rhodri Glyn Thomas

became the Heritage Minister (which includes responsibility for the Welsh language) and

Elin Jones became Rural Affairs Minister. Each of these appointments allows for a fresh

injection of ideas and in some policy areas a far greater commitment to the mainstreaming

of bilingualism. Of the many strident promises made in ‘One Wales’ (2007) three areas

are worthy of note. They relate to Welsh- medium education, to legislative reform and to

a greater recognition of the role which Wales might play within the international commu-

nity. In terms of Welsh- medium education, ‘One Wales’ states:

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 703

We will set out a new policy agreement with Local Education Authorities to require

them to assess the demand for Welsh- medium education, including surveying parental

wishes, and to produce a resulting School Organisation Plan, setting out clear steps to

meet needs. We will create a national Welsh- medium Education Strategy to develop

effective provision from nursery through to further and higher education backed up

by an implementation programme. We will establish a Welsh- medium Higher Edu-

cation Network – the Federal College – in order to ensure Welsh- medium provision

in our universities. We will explore the establishment of a Welsh for Adults Unit with

suffi cient funding, giving priority to tutor education. (p. 22)

The mandate also resolves to regenerate communities, establish credit unions, reduce pov-

erty, maintain sustainable environments, support rural development, promote local food

procurement, and encourage renewable technologies.

On the Welsh language itself, the document confi rms the thrust of Iaith Pawb and

asserts that

We will be seeking enhanced legislative competence on the Welsh language. Jointly we

will work to extend the scope of the Welsh Language Legislative Competence Order

included in the Assembly government’s fi rst year legislative programme, with a view

to a new Assembly Measure to confi rm offi cial status for both Welsh and English lin-

guistic rights in the provision of services and the establishment of the post of Language

Commissioner. (p. 34)

Other features include working in tandem with Westminster to press the case for Welsh

becoming an offi cial EU language, enhancing the use of Welsh in cyberspace, address-

ing the effects of population migration imbalances, promoting the representation of Wales

within international agencies, drawing on the collective energies of the Welsh diaspora. In

other words, realizing a wish list of activities which give recognition to Wales’s independ-

ent character and role within the wider world in the manner of Québec and Catalunya.

When he was the responsible Minister, Rhodri Glyn Thomas proved an effective oper-

ator in clearing several log- jams and in releasing more resources for publishing, the arts

and live theatre, not least of which was a substantial re- negotiation of the debts and annual

subsidy given to the Millennium Centre. His successor A. F. Jones made determined state-

ments about the need to empower the National Assembly to legislate for the needs of the

Welsh language. In broad terms, therefore, there is far greater impetus now to promote

and regulate the Welsh language across a wide variety of fi elds.

CONCLUSION

The vitality of Welsh cannot be doubted. There is a quantum difference between the cur-

rent period and the 1970s and 1980s of the last century in almost all aspects of education,

public service provision, the mass media and IT applications. And yet, many entertain sig-

nifi cant doubts about the ability of the base of speakers to sustain itself over the long term.

The growth in the number of speakers, produced by both the statutory education system

and the adult learners’ programmes, is very welcome. Observers are more sanguine, how-

ever, when it is revealed that less than 6.5 per cent of all families in Wales are made up of

parents and children who are capable of speaking Welsh. Further, the majority of Welsh

speakers are to be found in domestic contexts where they are the only speakers of the

704 THE SOCIOLINGUISTICS OF THE CELTIC LANGUAGES

language within the household, either as a result of their families having grown up and

relocated or because the younger speakers have acquired a profi ciency in school which

is not shared by their parents. Clearly such language isolation does not bode well for the

long- term reproduction of either the language or its related culture.

The principal agency of language and governance, the Welsh Language Board, has

matured to become a professional, para- public institution, an arm of government backed by

UK parliamentary legislation, a champion of radical and innovative measures, and a critic

of many aspects of Welsh public and commercial life. Its actions and underlying approach

have been criticized mainly in respect of its grant allocation decisions, its prioritizing of

some cultural and youth- rated activities over others, and its regulatory behaviour vis- à- vis

some public institutions. It has also been accused of being naive in advancing neo- liberal

presumptions regarding its capacity to intervene in the marketplace, to infl uence the lan-

guage choice and child- rearing practices of parents and for its quango- like relationship

with government. However, because of its relative autonomy of action it has forged a wide

variety of enabling partnerships, at one step removed from the day- to- day concerns of

government, thereby acquiring its own legitimacy as the authoritative language- planning

body. It has also mobilized a genuine discussion on the question of language rights and the

establishment of a Language Commissioner. This has been the long- term aim of selected

political parties, Cymdeithas yr Iaith and language advocates. The enforcement of com-

pliance with Welsh- language schemes is dependent on action by the National Assembly

for Wales. Public bodies believe that the board has far more powers than it actually has to

enforce its recommendations. Consequently, the largely constructive, consensual approach

of the WLB, especially when dealing with large organizations that do not have an obvi-

ous self- interest in promoting bilingualism, has paid off. More recently National Assembly

decisions have strengthened the WLB and made more urgent its deliberations in terms of

constructing a bilingual society.

Despite the professional competence and care of language- planning agencies, the ulti-

mate future of the language rests on the myriad inter- connected decisions of speakers,

acting either as individuals or in concert. A minority language cannot survive as a targeted

resource or as a social network phenomenon; it must be the normal natural communication

medium of distinct communities. Even though the number of Welsh speakers is increasing

in the anglicized south- east, this growth must be tempered by the realization that the lan-

guage continually loses ground in the ‘heartland’ areas. Any expansion in the use of Welsh,

with its recognized offi cial status, will have only a limited impact if the numbers of native

speakers diminish and if Welsh- speaking communities are gradually dispersed. Survival of

the language demands careful planning and resources at all levels – educational, economic,

social, institutional and cultural. But ultimately it requires stamina, enthusiasm, and above

all sheer determination on the part of its speakers to make it vibrant and essential.

NOTES

1 Our interpretation of the ‘sociolinguistics’ of Welsh is broad here; for a treatment which details

the linguistic aspects more, see Coupland (2008).

2 The most refi ned and developed form of their knowledge and training is portrayed in Gra-

madegau’r Penceirddiaid. Although the grammar section is basically a translation of Latin

grammar (Donatus and Priscian), a substantial section deals with the art of poetry. See Wil-

liams and Jones (1934: xiii–xxxix); Jarman and Hughes (1979: 74–86); Matonis (1981: 128);

and Parry (1962). Further insights concerning the status and professionalism of the bards are

given in the Welsh Laws.

THE SOCIOLINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF WELSH 705

3 The repertoire consisted of three main types:

(a) those of Welsh origin;

(b) those which show evidence of European infl uence;

(c) translations.

There is therefore evidence of European cultural and linguistic contact but that in fact enriched

the native Welsh tradition and illustrated the vitality and resourcefulness of the Welsh language

itself.

4 William Salesbury ‘Oll Synnwyr Pen Kembero Ygyd’, in Hughes (ed.) (1951: 10–11).

5 Geolinguistics in general and certainly in Wales owes much to the meticulous and imaginative

work of John Aitchison and Harold Carter, who concentrated on census analysis, W. T. R. Pryce

who reconstructed historical church records to map linguistic changes, and Colin H. Williams

who used his interpretations of the spatial analysis of Welsh to inform public policy and lan-

guage planning studies.

6 See Lieberson 1972, 1980 where it is shown that societal language shift (French/English) is

due to intergenerational switching. Bilinguals pass on one of the two languages to the next gen-

eration. E. G. Lewis (1972) cites migration as a dominant factor in language shift in what used

to be the USSR.

7 See Gal (1979), Dorian (1980) and Timm (1980). In each of these studies the language erosion

and accompanying bilingualism and the following language shift were in the direction of the

high- status language.

8 For details and a comprehensive discussion see Roberts (1998).

9 In 1885 Dan Isaac Davies HMI published a pamphlet ‘Tair Miliwn o Gymry Dwyieithog’ –

three million bilinguals by 1890. He was obviously optimistic that the system would create

bilinguals of both Welsh and English monoglots.

10 Southall (1895). English speakers who migrated to Cardiganshire were assimilated into the

Welsh- speaking communities because their numbers made that possible: ‘Carefully consid-

ered, the evidence shows pretty conclusively that Welsh must have been acquired by thousands

of English settlers or their immediate descendants since 1847, who have thus become success-

ful candidates for initiation into the circle of Welsh nationality’ (Southall 1895: 17).

11 This call was repeated in Williams and Evas (1997) and implemented in the successful Twf

Project run by the Welsh Language Board and Cwmni Iaith.

12 E. G. Lewis (1978). He suggests that the Welsh language is increasingly identifi ed with a

declining rural economy and a vanishing culture. As a result Welsh is seen as the language

of intimacy and ethnic affi liation rather than as the language of economic interests. Migra-

tion as a factor affecting language shift is well documented. See Tabouret- Keller (1968, 1972);

E. G. Lewis (1978); Dressler and Wodak- Leodolter (1977); and Timm (1980).

13 Carter (1989) examined the geographical distribution in 1981 of those born in Wales and also

examined the change in the percentage of Welsh speakers in the decade 1971–81: ‘It is this

which has induced the present crisis of the language for the reservoir which continually renewed

it is in danger of drying up’ (Carter 1989: 21). See James (1986: 69–70). Between 1971 and

1977 it is estimated that 12,000 immigrants moved into Anglesey and of those only 2,150 (18

per cent) were Welsh speaking. In fact 73 per cent of all immigrants came from England.

14 The arrival of small numbers of monoglot English children at a small rural school affected

the linguistic balance and often resulted in a switch from Welsh- medium teaching to English-

medium teaching.

15 Ambrose and Williams (1981) conclude that the Welsh language is not necessarily safe in areas

where 80 per cent of the inhabitants speak the language, and they stress that it is not necessarily

dying in areas where 10 per cent or less of the population do so. Cardiff is, of course, a case in

point. Welsh speakers constitute approximately 11 per cent of its population and yet in recent

years the area has seen a great increase in the number of Welsh speakers. It is suggestive of

future trends that Welsh- language cultural and educational facilities are better in this area than

in some other areas with a high density of Welsh speakers.

16 This is obviously the legacy of an educational system which taught every subject except Welsh

through the medium of English.