Ямпольский М. Физиология символического. Возвращение Левиафана: Политическая теология, репрезентация власти и конец Старого режима

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

804 М. Ямпольский. Физиология символического

is fused into an organic unity of the king's body. In such terms —

nation is a heterogeneous artificial assemblage, and the king — it's

redeemer into an organic unity. Even Hegel claimed that the nation

as abstraction needs a face of a sovereign to acquire reality. Without

such a face the people remain, according to him, only an amorphous

mass. Allegorical reading of the monarchic body radically reverses

these relations. Now it's no longer a monarch that incorporates the

organic unity of the commonwealth, but contrariwise by his own

allegorical artificiality he obstructs the constitution of this unity.

A new model of a democratic representation was gradually

coined. It was no more a personification, an incarnation in one figure,

but (as a member of the Convention Jean-Louis Seconds formulated

it) the new political representation should imitate a polyp — which is

at the same time an animal and an "individual people" (un peuple

animal et individuel). The abstraction of the Nation should now be

represented not by a king but by Robespierre's Supreme Being that

preserved all characteristics of a politico-theological abstraction. The

composite allegorical being doesn't correspond to the task of

unification because of an increasing process of a homogenization of

the society itself. This homogenization is carried into effect thanks

to a growing exclusion of every heterogeneous element. The organicity

is achieved by exclusion, first of all, of the monarch himself'— a

figure above the social body, a monstrous allegory and mimetic mirror

of power.

The trial of Louis XVI was a dramatic attempt to dissociate the

society from the king. This dissociation expulsed the king outside

the community, i. e. the communal law and thus excluded the king

from the system of French jurisprudence. However the king was

generally considered as a constituting and not a representative power.

It meant that France itself was deriving its existence (its "face") from

the king and thus was not able to prosecute him for a break in a

contract of representation. Finally Robespierre tried to justify the

execution of the king as a simple murder on the account of the

Nation. Saint-Just claimed that the only way to deal with the king is

to look at him as at the external enemy. The execution of Louis XVI

had a clear savor of the murder that it never lost. It could be

"justified" only in terms of exception and sacrality. The ambiguity

of this event corresponded quite well to the ambiguity of the sacred

itself. Latin Sacer equally defines the divine and the most abject aspect

of a person who is sacrificed. The sacred aspect of the supreme

sacrifice revealed monstrosity of the figure of exclusion — of a

murdered king.

The fight between the defenders of the king and his persecutors

focused on the interpretation of the execution. For king's supporters

it was primarily a sacrifice, for his detractors — an event without

any symbolic significance. The revolutionaries planned the execution

as a final blow to monarchic symbolism. Louis XVI, however, tried

to transform his own beheading into a Christological gesture of a

Summary

805

redeeming martyrdom. He was consciously copying the behavior of

Charles I who succeeded to present his death as a sacrifice. In spite

of all the efforts Louis acted rather as a pharmakos — a purifying

sacrifice that absorbs into oneself all dirt, sins, wickedness without

any chance of his or her own redemption.

The failure to transform an execution into a sacrifice is grounded

in a new status of a sovereign body. First of all it's due to a general

collapse of symbolism of this body, but also to an impossibility to

imitate Christ's sacrifice whose meaning was exactly to stop all

sacrifices forever, i. e. to be the last and inimitable sacrifice. The

transfiguration of the sovereign body has already happened when it

was transformed into a pure representation of one's own image —

a "portrait of a portrait", according to Louis Marin. Monarchic power

is already an "effect of figuration" — a result of transfiguration of a

body into an image. Christ and the king are figures — both "leave"

their body in an excess of a figurative disembodiment. However both

figures are fundamentally different to a point of the absolute non-

similarity (Pascal). Paradoxically, only when the king is not

surrounded by an aura of figuration that generates his power,

similarity between him and the Man of Sorrows is unmistakably

revealed, i.e. the king reveals his similarity to Christ only when he

is no more a king.

The failure of the sacrifice also manifests the failure of a

mechanism of a discarnation that produces figures. The body of the

king preserves its materiality in spite of all manipulations applied to

it. This materiality takes form of the so called "corps d'effroi" —

allegorical composite monsters — or of simple bestiality. The beast

that usually represented the king in popular imagery was a pig. These

representations included the whole bunch of motifs associated with

hogs in popular mythology — impotence (castration), gluttony,

leprosy etc. Many of these motifs were usually applied to another

group of excluded individuals — the Jews. The weird contamination

of anti-monarchic imagery with the anti-Semitic one — is one of

the most striking features of a discourse desecrating the monarchy.

The association of the king with a pig and a Jew made any possibility

of sacrificial model unrealistic and doomed Louis to remain homo

sacer — a simple and unredeemable pharmakon. The sovereign's

transgressiveness had no more relations to a symbolic dimension of

a constituent power, but was confined to the domain of bestiality. During

the Revolution, animals were often used for a profanation of the

sacred, of the symbolical. Finally this role of the desecration is

prescribed to the incarnation of the symbolic par excellence. The king

made animal destroyed the foundation of his own symbolic power.

In such a situation an execution of the king-hog was nothing else

than a gesture of foundation of a new symbolic order, of a new society

and of a new state.

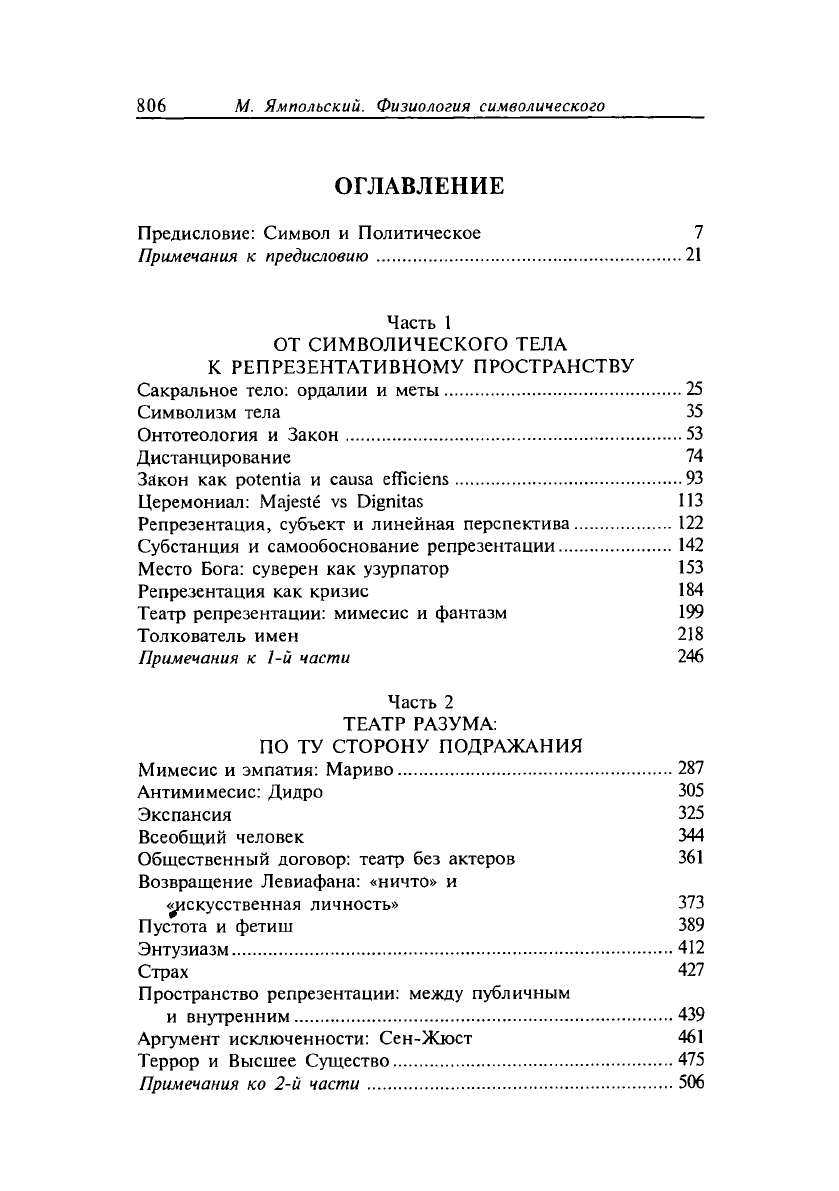

806 М. Ямпольский. Физиология символического

ОГЛАВЛЕНИЕ

Предисловие: Символ и Политическое 7

Примечания к предисловию 21

Часть 1

ОТ СИМВОЛИЧЕСКОГО ТЕЛА

К РЕПРЕЗЕНТАТИВНОМУ ПРОСТРАНСТВУ

Сакральное тело: ордалии и меты 25

Символизм тела 35

Онтотеология и Закон 53

Дистанцирование 74

Закон как potentia и causa efficiens 93

Церемониал: Majeste vs Dignitas 113

Репрезентация, субъект и линейная перспектива 122

Субстанция и самообоснование репрезентации 142

Место Бога: суверен как узурпатор 153

Репрезентация как кризис 184

Театр репрезентации: мимесис и фантазм 199

Толкователь имен 218

Примечания к 1-й части 246

Часть 2

ТЕАТР РАЗУМА:

ПО ТУ СТОРОНУ ПОДРАЖАНИЯ

Мимесис и эмпатия: Мариво 287

Антимимесис: Дидро 305

Экспансия 325

Всеобщий человек 344

Общественный договор: театр без актеров 361

Возвращение Левиафана: «ничто» и

«искусственная личность» 373

Пустота и фетиш 389

Энтузиазм 412

Страх 427

Пространство репрезентации: между публичным

и внутренним 439

Аргумент исключенности: Сен-Жюст 461

Террор и Высшее Существо 475

Примечания ко 2-й части 506

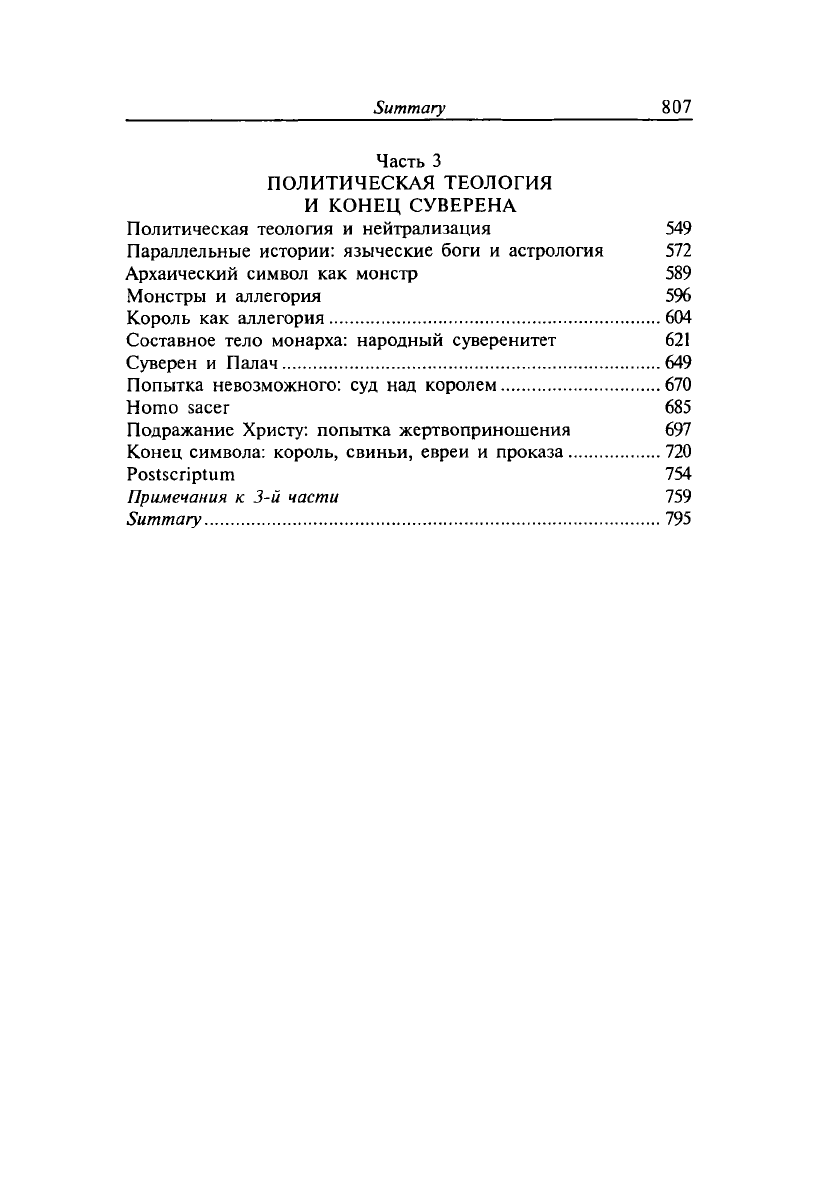

Summary

807

Часть 3

ПОЛИТИЧЕСКАЯ ТЕОЛОГИЯ

И КОНЕЦ СУВЕРЕНА

Политическая теология и нейтрализация 549

Параллельные истории: языческие боги и астрология 572

Архаический символ как монстр 589

Монстры и аллегория 596

Король как аллегория 604

Составное тело монарха: народный суверенитет 621

Суверен и Палач 649

Попытка невозможного: суд над королем 670

Homo sacer 685

Подражание Христу: попытка жертвоприношения 697

Конец символа: король, свиньи, евреи и проказа 720

Postscriptum 754

Примечания к 3-й части 759

Summary 795