Stewart J. College Algebra: Concepts and Contexts

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

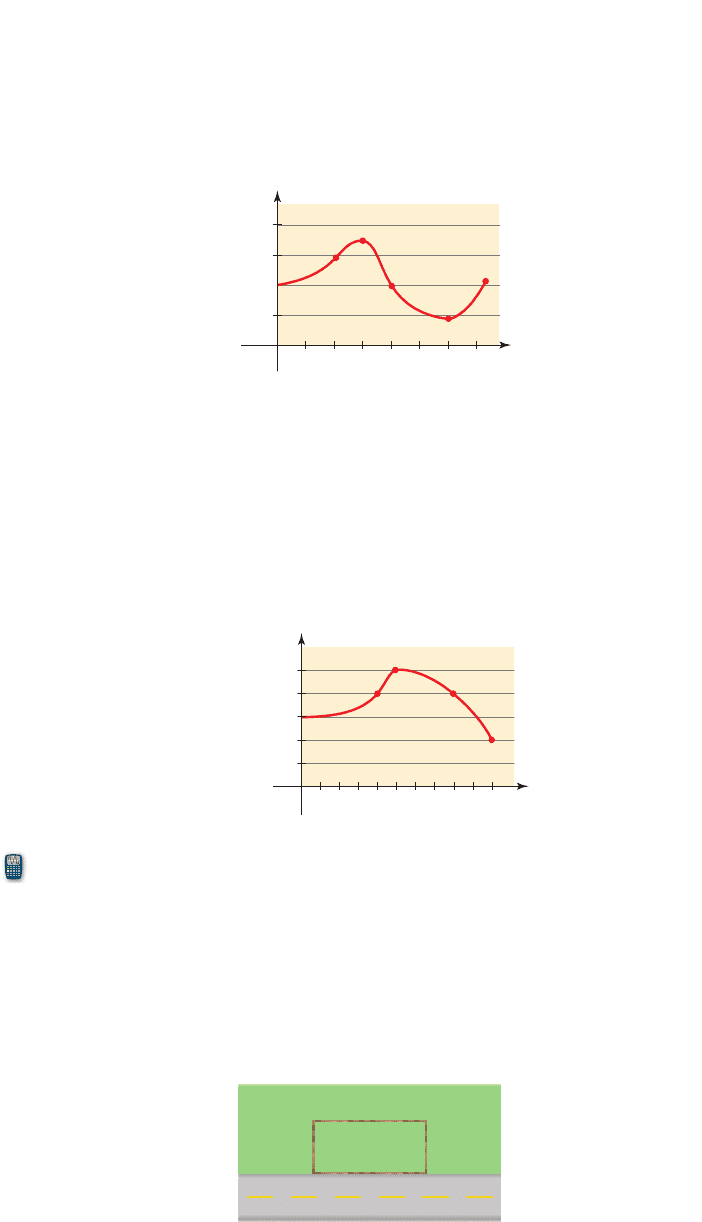

75. Depth of a Reservoir The graph shows the depth of water W in a reservoir over a

1-year period, as a function of the number of days x since the beginning of the year.

(a) What are the domain and range of W?

(b) Find the intervals on which the function W is increasing and on which it is

decreasing.

(c) What is the water level in the reservoir on the 100th day?

(d) What was the highest water level in this period, and on what day was it attained?

124 CHAPTER 1

■

Data, Functions, and Models

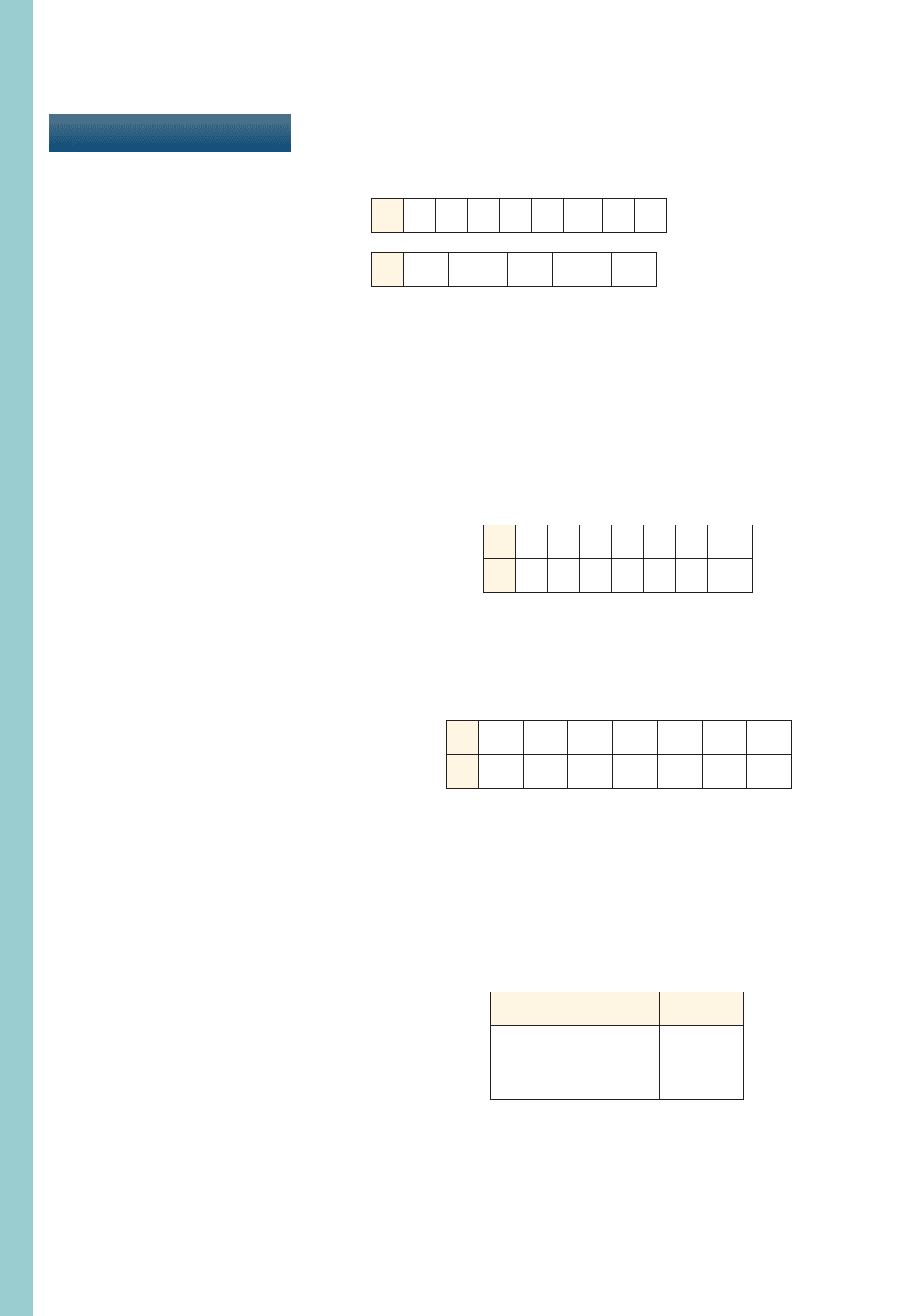

77. Fencing a Garden Plot A property owner wants to fence a garden plot adjacent to a

road, as shown in the figure. The fencing next to the road must be sturdier and costs $5

per foot, but the other fencing costs just $3 per foot. The garden is to have an area of

.

(a) Find a function C that models the cost of fencing the garden.

(b) Use a graphing calculator to find the garden dimensions that minimize the cost of

fencing.

(c) If the owner has at most $600 to spend on fencing, find the range of lengths he can

fence along the road.

1200 ft

2

x

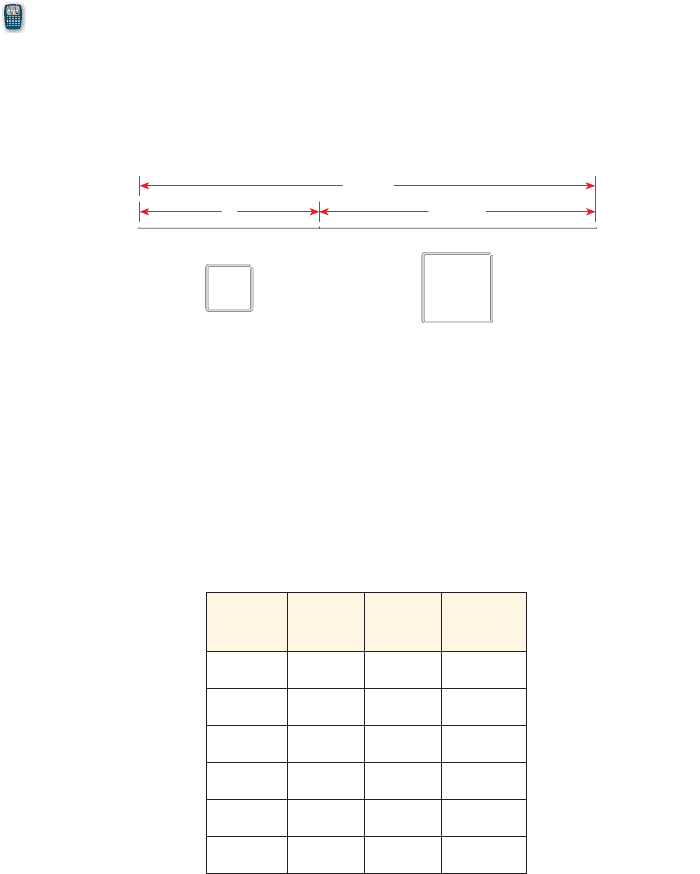

Years

P

(thousands)

0

10

20

30

40

50

10 20 30 40 50

x

x

Days

W (ft)

0

25

50

75

100

100 200 300

76. Population Growth and Decline The graph below shows the population P in a

small industrial city from 1950 to 2000. The variable x represents the number of

years since 1950.

(a) What are the domain and range of P?

(b) Find the intervals on which the function P is increasing and on which it is

decreasing.

(c) What was the largest population in this time period, and in what year was it

attained?

CHAPTER 1

■

Review Exercises 125

10 cm

x 10-x

Length

(in.)

Width

(in.)

Height

(in.)

Volume

(in

3

)

36 14

40 10

12 12

16 8

72 3

10 10

79. Mailing a Package One measure of the size of a package, used by the postal service

in many countries, is “length plus girth”—that is, the length of the package plus the

distance around it. So if a package has length l, width w, and height h, then its size S is

given by the formula

(a) The maximum size parcel that the U.S. Postal Service will accept has a length plus

girth of 84 in. What is the width of a package of this maximum size if its length is

64 in. and its width equals its height?

(b) Using the fact that the volume of a box is , complete the following table for

various packages that are all assumed to have a length plus girth equal to 84 in.

V = lwh

S = l + 2w + 2h.

78. Maximizing Area A wire 10 cm long is cut into two pieces, one of length x and the

other of length , as shown in the figure. Each piece is bent into the shape of a

square.

(a) Find a function A that models the total area enclosed by the two squares.

(b) Use a graphing calculator to find the value of x that minimizes the total area of the

two squares.

10 - x

126 CHAPTER 1

■

Data, Functions, and Models

TEST

1. Find the average and the median of the values of x given in the list.

(a)

(b)

2. A set of two-variable data is given.

(a) Express the data as a relation (a set of ordered pairs), using x as the input and y as

the output.

(b) Find the domain and range of the relation.

(c) Make a scatter plot of the data.

(d) Is the relation a function? Why or why not?

(e) Does there appear to be a relationship between the variables? If so, describe the

relationship.

(f) Which input(s) correspond to the output 5?

3. A set of two-variable data is given.

(a) Find a linear model for the data.

(b) Use the model to predict the outputs for the inputs 4.5 and 10.

(c) Sketch a graph of the model.

4. An equation in two variables is given. Does the equation define y as a function of x?

(a)

(b)

5. The function f has the verbal description “Square, subtract 4, then divide by 5.” Express

the function algebraically using function notation.

6. A car dealership is offering discounts to buyers of new cars, with the amount of the

discount based on the original price of the car, as indicated in the following table.

x

2

+ 3y = 9

3x + y

2

= 9

x 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

y 4.0 4.5 5.0 5.5 6.0 6.5 7.0

x 0 1 2 3 4 5 6

y 1 5 7 7 5 1

-5

x 1.2

-2.4

4.4

-5.1

3.9

x 7 1 6 6 2 10 4 0

CHAPTER

1

Original price x ($) Discount

x 6 20,000

20% of x

20,000 … x 6 40,000

$5000

x Ú 40,000

$8000

(a) Let be the discounted price of a car whose original price was x dollars.

Express the function f as a piecewise defined function.

(b) Evaluate , , , and .

(c) What two different values of x both give a discounted price of $34,000?

f 140,0002f 138,0002f 122,0002f 119,000 2

f 1x 2

7. Ella is an editor of gardening books. She is planning a reception at a bookstore to

promote a new book by one of her authors. Use of the facility costs $300, and

refreshments for the guests cost $4 per person.

(a) Find a function C that models the total cost of the reception if x guests attend.

(b) Sketch a graph of C.

(c) Evaluate C(50) and C(200). What do these numbers represent? Plot the points that

correspond to these values on your graph.

(d) If the total cost of the reception was $600, how many guests attended?

8. When a bullet is fired straight up with muzzle velocity 800 ft/s, its height above the

ground after t seconds is given by the function

(a) Use a graphing calculator to draw a graph of h.

(b) Use your graph to determine the maximum height that the bullet reaches and the

time when it reaches this height.

(c) When does the bullet fall back to ground level?

(d) For what time interval is h decreasing? What is happening to the bullet during this

time?

9. The surface area of a rectangular box with length l, width w, and height h is given by

the formula .

(a) Find the surface area of a box that is 30 cm long, 12 cm wide, and 4 cm high.

(b) Find a formula that expresses h in terms of the other variables.

A = 2lw + 2lh + 2wh

h1t 2= 800t - 16t

2

.

CHAPTER 1

■

Test 127

Bias in Presenting Data

OBJECTIVE To learn to avoid misleading ways of presenting data

In this chapter we studied how data can be used to discover hidden relationships in

the real world. But collecting and analyzing data are human activities, so they are not

immune from bias. When we are looking for trends in data, our goal should be to dis-

cover some true property of the thing or process we are studying and not merely to

support a preconceived opinion. However, it sometimes happens that data are pre-

sented in a misleading way to support a hypothesis that is not valid. This is some-

times called fudging the data, that is, reporting only part of the data (the part that

supports our hypothesis) or even simply making up false data. Mark Twain suc-

cinctly described these practices when he said, “People commonly use statistics like

a drunk man uses a lamppost; for support rather than illumination.”

Here’s a simple example of how we may choose to present data in a biased fash-

ion. Tom and Harry compete in a two-man race, which Tom wins and Harry loses.

Harry tells his friends, “I came in second, and Tom came in next-to-last.” Although

correct, Harry’s statement gives a misleading impression of what actually happened.

But misrepresenting or misinterpreting data is not always just silly—it can be a

very serious matter. For example, if experimental data on the effectiveness of a new

drug are misrepresented to bolster the claim of its effectiveness, the result could be

tragic to patients using the drug. So in using data, as in all scientific activities, the

goal is to discover truth and to present the results of our discoveries as accurately and

as fairly as possible. In this exploration we investigate different ways in which data

can be misrepresented, as a warning to avoid such practices.

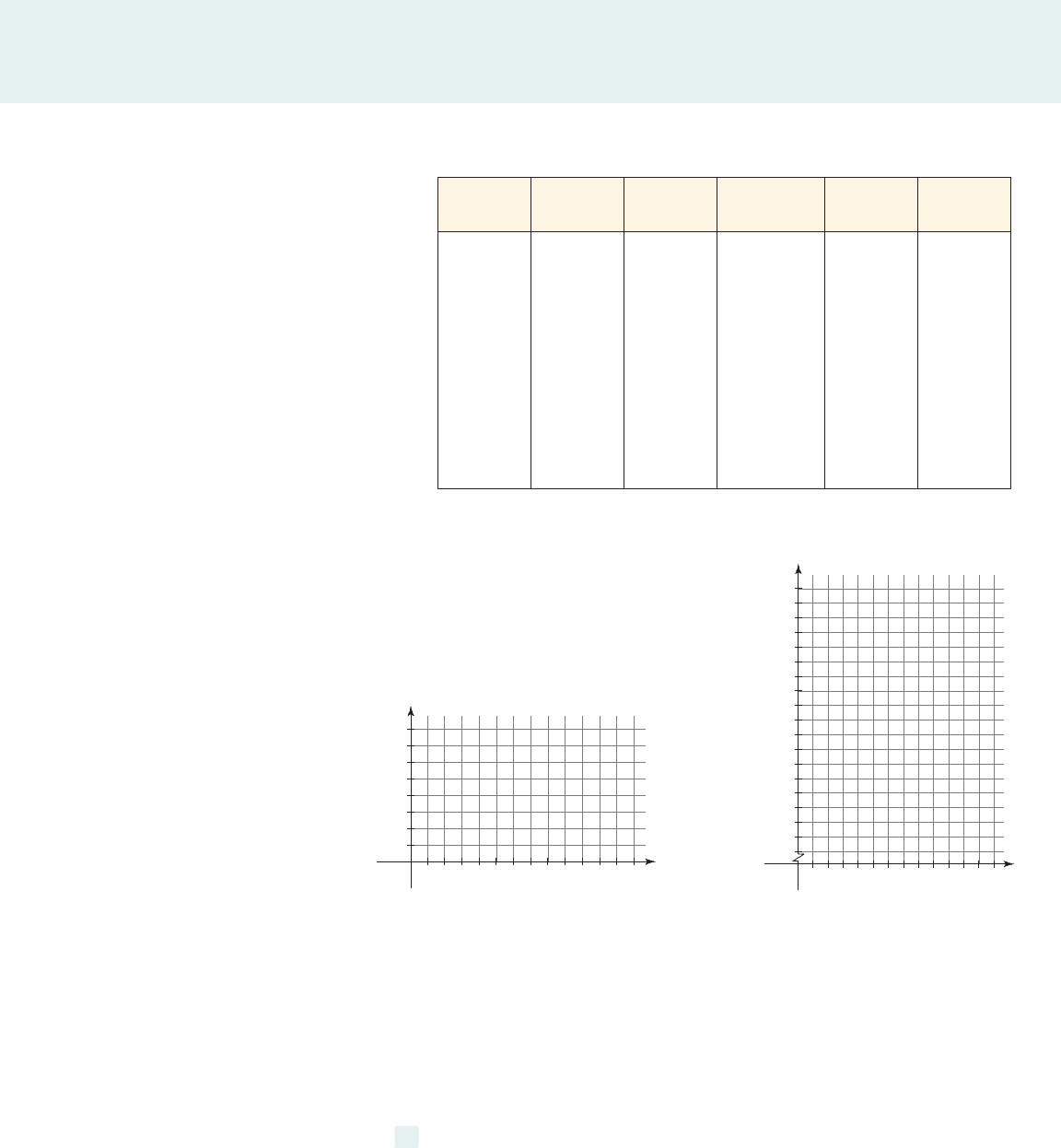

I. Misleading Graphs

Although graphs are useful in visualizing data, they can also be misleading. One

common way to mislead is to start the vertical axis well above zero. This makes small

variations in data look large. The following graphs show Tom’s and Pat’s annual

salaries. Does Pat make a lot more money than Tom, or do they make about the same?

Look carefully at the scale on the y-axis before answering this question.

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

1

60,000

59,000

61,000

62,000

63,000

64,000

65,000

Tom Pat

10,000

00

20,000

30,000

40,000

50,000

60,000

70,000

Tom Pat

1. The business manager of a furniture company obtains the following data

from the accounts department. She needs to present a report on the financial

state of the company to the executive board at their annual meeting.

128 CHAPTER 1

Winner: Tom; Loser: Harry

www.grinningplanet.com

(a) Plot the profit data on each of the axes shown below.

Month

Labor

(ⴛ $1000)

Materials

(ⴛ $1000)

Advertising

(ⴛ $1000)

Revenue

(ⴛ $1000)

Profit

(ⴛ $1000)

Jan. 320 247 14 709 122

Feb. 343 330 12 810 118

Mar. 332 330 16 806 123

Apr. 367 295 7 795 120

May 405 370 33 938 124

June 430 424 18 1002 123

July 440 407 13 992 126

Aug. 427 395 12 967 128

Sept. 392 363 21 912 130

Oct. 295 284 6 722 131

Nov. 288 260 28 714 132

Dec. 315 310 8 784 134

130

132

134

116

118

120

122

124

126

128

Profit

2468

Month

10 12

0

(b) The two graphs you sketched in part (a) display the same information. But

which gives the impression that profit increased dramatically? What graph

gives a more realistic impression of profit growth for this year?

(c) The business manager also wishes to give a graph of monthly revenue in

her report. Sketch two graphs of the monthly revenue: one that gives the

impression that revenues were dramatically higher in the middle of the

year and one that shows that revenue remained more or less steady

throughout the year.

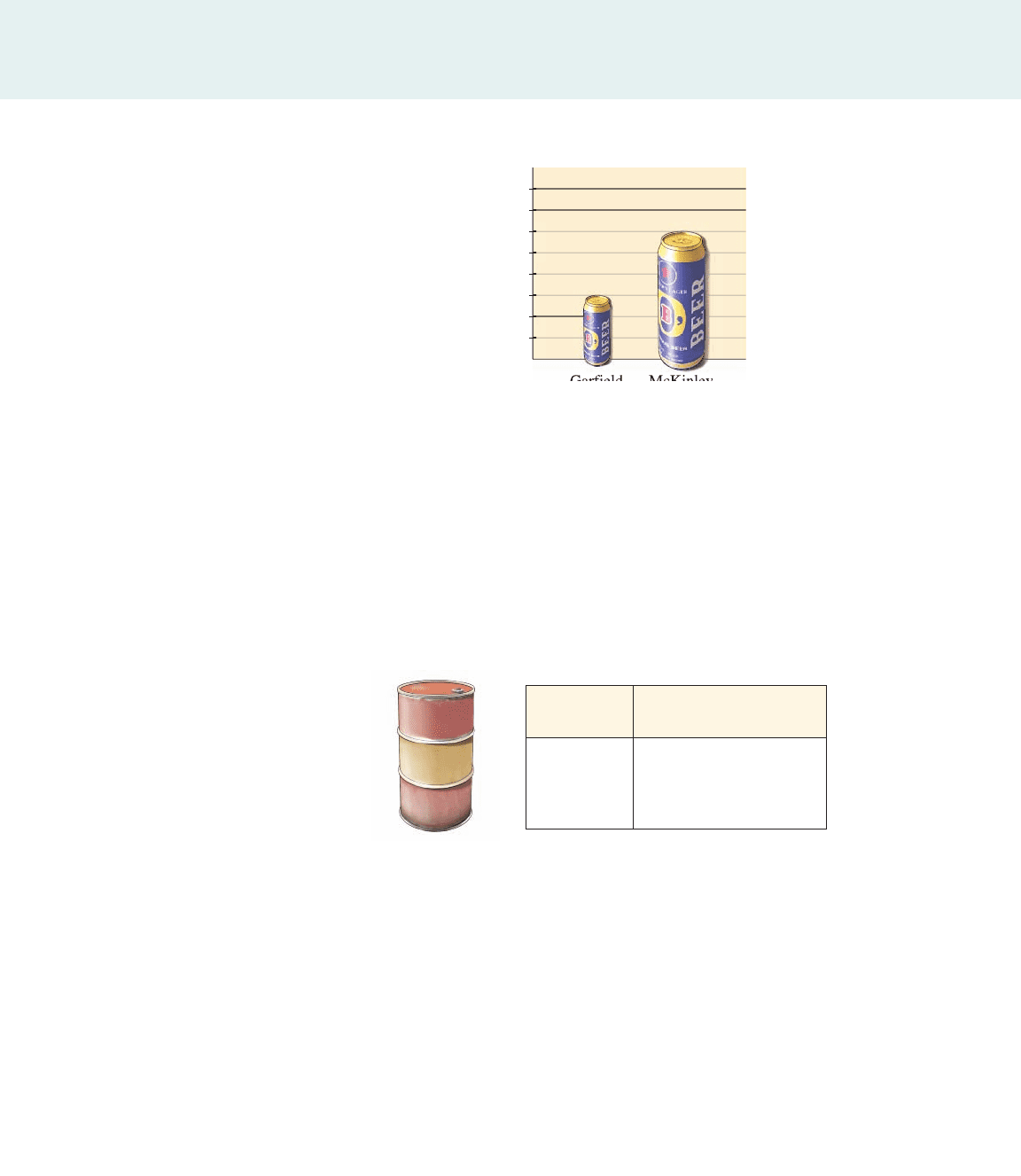

2. The students at James Garfield College drink on average about 3 liters of beer

each per month. The rival college across town, William McKinley University,

has the reputation of being a “party school.” Its students drink about 6 liters of

beer each per month. In the following graph, each college’s average beer

consumption is represented by the height of a beer can.

200

150

100

50

Profit

2468

Month

10 12

0

x

y

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

EXPLORATIONS 129

Garfield

McKinley

Colle

ge

Beer

(

L

)

6

3

II. Are We Measuring the Right Thing?

Suppose we are told that one school district employs 50 science teachers while an-

other district has just 5. Can we assume that the parents in the first district care

more about science education than those in the second? Of course not. The rela-

tive sizes of the school districts must be taken into account before we can come to

any conclusions. If the population of the first district is ten times that of the sec-

ond, then both have the same relative proportion of science teachers. In many

cases data have to be properly scaled to understand their significance. Let’s ana-

lyze the following data about two of the leading causes of death in the United

States.

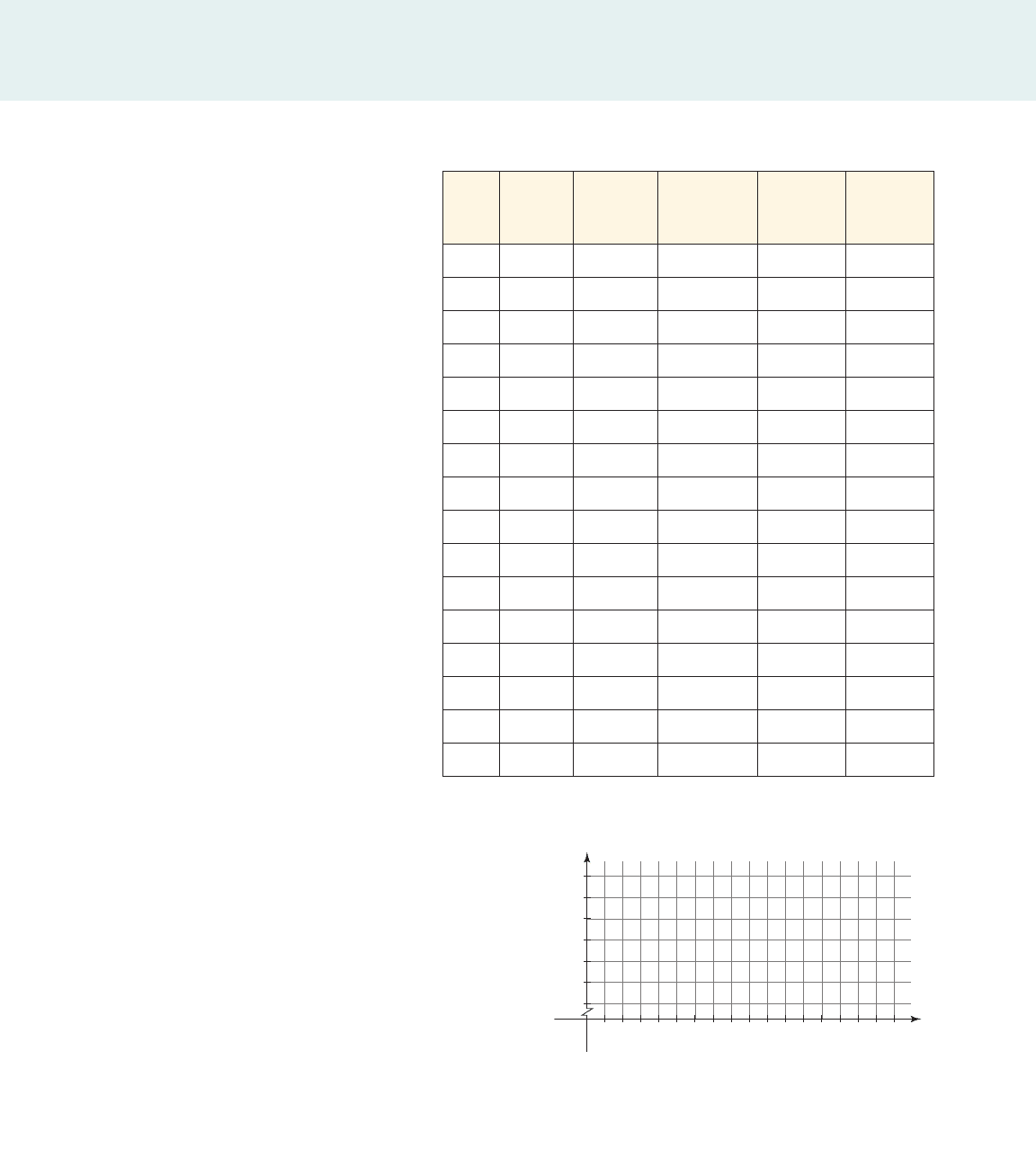

1. The following table gives the number of deaths from all forms of cancer and

the number of deaths from automobile accidents in the United States from

1988 to 2003, together with population data for those years.

130 CHAPTER 1

(a) Does the graph give the correct impression about the relative amount of

beer consumed at each college? Why is using images of three-dimensional

cans instead of just drawing a plain bar graph deceptive? [Hint: By what

factor does the volume of a cylindrical can increase if its height and radius

are doubled?]

(b) The table gives estimates of the daily oil consumption of four large

countries. Draw a bar graph of the data, using the height of a three-

dimensional oil barrel to represent oil consumption. How does the graph

give a misleading impression of the data?

Country

Oil consumption per day

(millions of barrels)

United States 20.7

China 7.9

Russia 2.7

Mexico 2.1

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

(a) Graph the cancer mortality data on the given axes.

Year

Cancer

deaths

Auto

fatalities

Population

(ⴛ $1000)

Cancer

mortality

rate

Auto

mortality

rate

1988 485,048 49,078 244,480

198.4 20.1

1989 496,152 47,575 246,819

1990 505,322 44,599 248,710

1991 514,657 41,508 252,177

1992 520,578 39,250 255,078

1993 529,904 40,150 257,783

1994 534,310 40,716 260,341

1995 538,455 41,817 262,755

1996 539,533 42,065 265,284

1997 539,577 42,013 267,636

1998 541,532 41,501 270,360

1999 549,838 41,611 272,737

2000 553,091 41,945 275,307

2001 553,768 42,196 284,869

2002 557,271 43,005 288,443

2003 556,902 42,884 290,810

(b) Describe the trend in the number of cancer deaths over this 16-year period.

Did the number of deaths per year increase, decrease, or hold steady?

450

500

550

600

Cancer deaths

(⫻ 1000)

1988

0

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000

Year

2002 2004

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

EXPLORATIONS 131

132 CHAPTER 1

(c) Complete the column in the table headed “Cancer mortality rate” by

calculating the cancer mortality rates per 100,000 population. For

example, the cancer death rate for 1988 is

(d) Graph the cancer mortality rate data on the given axes.

485,048

244,480,000

* 100,000 = 198.4

Year

National debt

(ⴛ $ trillion)

GDP

(ⴛ $ trillion)

National debt as

percent of GDP

1986 2.13 4.55

46.8%

1988 2.60 5.25

1990 3.23 5.85

1992 4.06 6.48

1994 4.69 7.23

1996 5.22 8.00

1998 5.53 8.95

2000 5.67 9.95

2002 6.23 10.59

2004 7.41 11.97

2006 8.51 13.49

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

180

190

200

210

Cancer

mortality

rate

1988

0

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000

Year

2002 2004

(e) Describe the general trend in the cancer mortality rate. Compare this to

the trend in the actual number of cancer deaths that you found in part (b).

Which do you think gives a better representation of the truth about cancer

deaths: the data on number of cancer deaths per year or the data on the

cancer mortality rate per year?

(f) Do the same analysis as in parts (a) to (e) for the automobile fatality data.

2. The U.S. public debt, usually referred to as the national debt, consists primarily

of bonds issued by the Department of the Treasury. Since it was founded in 1790,

the department has kept meticulous records of the national debt. The table below

gives the value of the national debt at 2-year intervals between 1986 and 2006.

(a) In which county were homicides most prevalent? Least prevalent? What

about burglaries?

(b) Of course, you know that Los Angeles has a lot more people than the other

counties in the table. What role does the population play in determining in

which county one would be least likely to be a victim of these crimes?

Use the population data below to determine a better measure of the

homicide rate and the burglary rate in each of these counties. Which

county has the highest homicide rate and which has the lowest? What

about burglary rates? Do you find your answers surprising?

Population data: Calaveras, 46,871; Humboldt, 128,376; Los Angeles, 9,935,475;

Monterey, 412,104; San Bernardino, 1,963,535; San Luis Obispo, 255,478;

Sonoma, 466,477; Stanislaus, 505,505.

EXPLORATIONS 133

County Homicides Burglaries

Calaveras 2 308

Humboldt 3 1334

Los Angeles 1068 58,861

Monterey 14 2809

San Bernardino 174 14,548

San Luis Obispo 4 1469

Sonoma 5 2340

Stanislaus 30 4836

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

■

EXPLORATIONS

(a) Sketch a graph of the national debt data. Describe any trends you see from

the graph.

(b) As the population of the United States grows, so does the economy. So it’s

probably not meaningful to compare the size of the national debt in 1790

(about 75 million dollars) to its current size (over 9 trillion dollars). To

take into account the overall size of the economy, economists calculate the

national debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP). For

example, for 1986 we get

Use similar calculations to complete the rest of the table.

(c) Sketch a graph of the percentage data that you calculated in part (b). Compare

your graph to the graph you sketched in part (a). What information does your

new graph provide that was not apparent from your graph in part (a)?

(d) What other factors do you think should be taken into account in consid-

ering the impact of the national debt? For example, does inflation play a

part in the size of the debt?

3. The following table gives the numbers of homicides and burglaries committed

in some California counties in 2005.

4.55

2.13

* 100 = 46.8%