Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

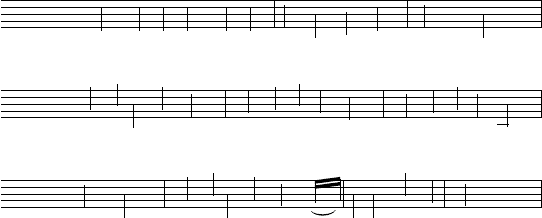

comedian; he was “The Great Vance” and played other character-types,

such as the “swell”—the exhibitionist toff or swaggering “man about

town.” Example 7.5 gives a taste of the very different character of music

and lyrics found in his celebrated swell song “The School of Jolly Dogs.”

To summarize phase 2, the identity of the performer remains sepa-

rate from that of the character portrayed. The cultural experience of

Cockneys is mediated by performers who are character-acting on the

music hall stage, and hence the appeal of the Cockney character-type

is broader in class terms than that of the parodic type.

182 Sounds of the Metropolis

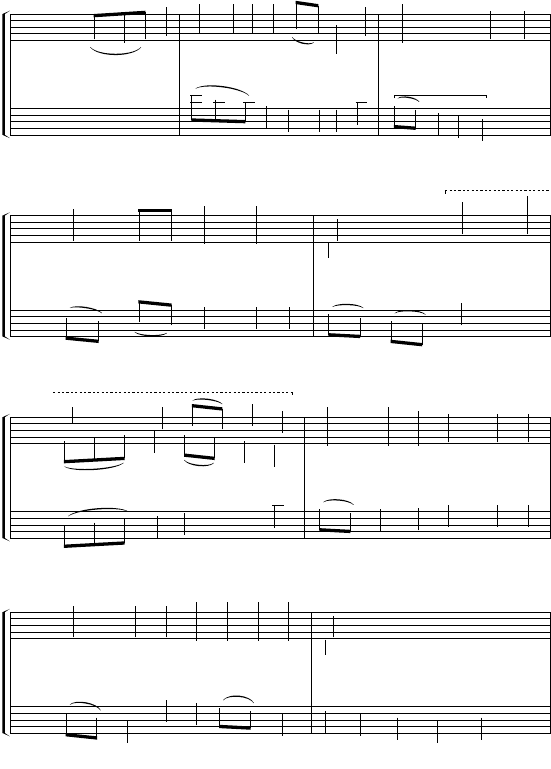

Example 7.3 Hallel Festival Hymn, excerpt, Sephardic liturgy,

published London 1857, transposed up a tone to aid comparison.

&

?

#

#

c

c

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

Hal - le -

Ó

.

.

j

œ

œ

r

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

lu et A - do-nai col go -

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

.

J

œ

R

œ

J

œ

J

œ

Hal - le - lu et A - do -

˙

˙#

œ

œ

œ

œ

yim Sha - be -

œ

œ

J

œ

J

œ

˙

nai col go-yim

&

?

#

#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

chu - hu col a - u -

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

j

œ

Sha - be - chu - hu col

˙

.

.

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

mim ki - ga -

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

a-u-mim

&

?

#

#

.

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

j

œ

bar a - le - nu chas -

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

.

œ

J

œ

ki - ga - bar a -

œ

œ#

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

do ve - e - met A - do -

œ

œ

J

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

j

œ

le - nu chas - do ve - e -

&

?

#

#

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ#

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

nai len - go - lam hal - le - lu -

œ

œ

J

œ

j

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

met A - do - nai len - go -

˙

Œ

yah.

˙

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ#

œ

lam hal - le - lu - yah.

(Relative major)

Phase 3: The Imagined Real

When we reach phase 3 in the 1880s, the performer is no longer thought

of as playing a role, but as being the character. In putting forward this

argument, I must warn against too close a link being made to Jean Bau-

drillard’s theory of simulacra. I am, certainly, claiming that just as in

Baudrillard’s third-order simulation, this third phase substitutes “signs

of the real for the real itself”;

32

but Baudrillard sees third-order simula-

tion as a feature of twentieth-century postmodernity: it is a “generation

by models of a real without origin or reality.”

33

As far as the music hall

Cockney ceases to relate to the real world and is, instead, generated by

stage models, this phenomenon might be considered to adumbrate the

type of postmodern hyperreality Baudrillard has in mind. He did, after

The Music Hall Cockney 183

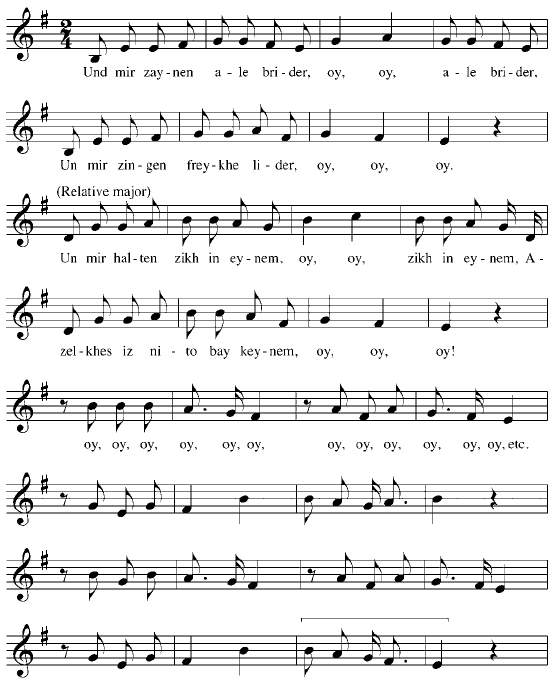

Example 7.4 “Ale Brider,” music traditional, the Yiddish text is

based on the poem “Akhdes” by Morris Winchevsky (1856–1932).

all, make the following pertinent comments on the role of art: “For a

long time now art has prefigured this transformation of everyday life.

Very quickly, the work of art redoubled itself as a manipulation of the

signs of art. . . . Thus art entered the phase of its own indefinite repro-

duction.”

34

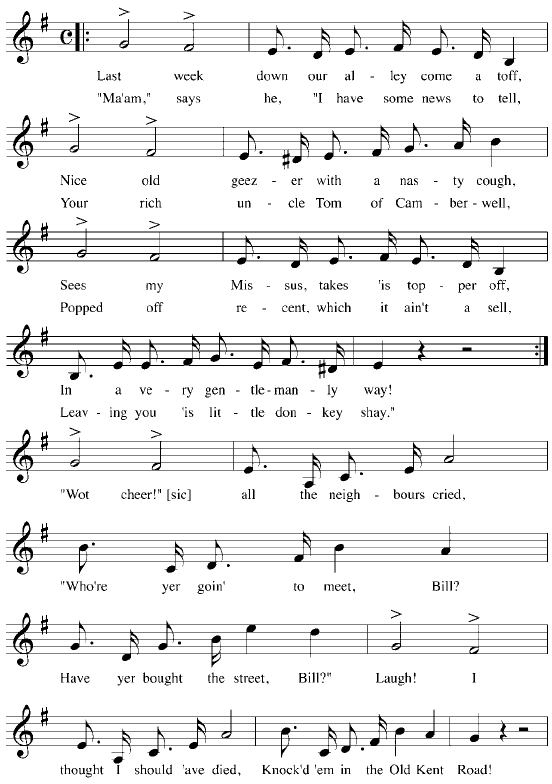

The music hall Cockney song becomes increasingly reflexive. Bessie

Bellwood’s “What Cheer ’Ria” (Herbert/Bellwood, 1885) has a title that

is a catch phrase in the making: in the lyrics to later songs (discussed

later) it moves, over time, to “Wot Cher” and “Wot’cher,” gradually

transforming itself into the “wotcha” still heard around the East End

today.

35

Bessie Bellwood (1857–96) was regarded as a real Cockney,

and she took a hand in the writing of this her best-known song. Actu-

ally, she was born Kathleen Mahoney, and as one might expect from

such a name, she started out as a singer of Irish songs.

36

So now we see

the influence of the Irish Cockney as well as the Jewish Cockney.

37

The song concerns someone attempting to rise above her station,

speculating a “bob” (1 shilling) for a posh seat in the stalls rather than

sitting with her friends in the cheap gallery seats (see ex. 7.6). It might

be thought that Jewish elements can still be detected in this song, in the

melodic style of the minor key verse and in the key change to the rel-

ative major for the refrain, but perhaps these features came now as a

influence from already-assimilated elements in other music hall songs.

From now on, it becomes difficult to say exactly where Jewish elements

come from, even in twentieth-century musical theatre such as Lionel

Bart’s Oliver! (1960).

38

A clear example of how inward-looking music hall song has be-

come in the 1880s appears in the chorus of “What Cheer ’Ria,” in the

line “she looks immensikoff [sic],” which refers back to a Cockney swell

song hit, “Immenseikoff,” written and sung by another star of the halls,

Arthur Lloyd (who, we might note, was actually Scottish) in 1873 (see

184 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 7.5 “Slap Bang, Here We Are Again, or The School of

Jolly Dogs,” excerpt, words and music by Harry Copeland

(London: D’Alcorn, c. 1865).

&

#

#

#

#

4

2

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

Fal de the ral, de the

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

ral lal li do

œ

œ

Slap, bang,

&

#

#

#

#

r

œ

r

œ

R

œ

r

œ

j

œ

‰

here we are a - gain,

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ

j

œ

‰

here we are a - gain,

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ

j

œ

‰

here we are a - gain,

&

#

#

#

#

œ

œ

Slap, bang,

r

œ

r

œ

R

œ

r

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

here we are a - gain, What

J

œ

J

œ

j

œ

j

œ

jol- ly dogs are

œ

Œ

we.

ex. 7.7). It is evident that this particular Cockney dandy has learned

from the Viennese popular style, since his song is a polka. Dance rhythms

from Vienna were making their mark on British music hall songs. An-

other swell song, “The Marquis of Camberwell Green,”

39

contains a

waltz refrain complete with a characteristic Viennese hemiola rhythm.

It should be mentioned, perhaps, that the swell was not a character-

type restricted to male performers: Jenny Hill (1850–96) performed in

drag, singing about another Cockney would-be swell, in “’Arry,” in the

1880s.

40

The character remained male, however; there was no London

music hall equivalent of the female swell or gommeuse seen in Parisian

cafés-concerts. The female counterpart of ’Arry and his pearly buttons

The Music Hall Cockney 185

Example 7.6 “What Cheer ’Ria,” chorus, words by Will Herbert,

music by Bessie Bellwood, arranged by George Ison (London:

Hopwood and Crew, 1885).

&

#

4

2

œ œ

What cheer

J

œ

.

œ

Ri - a?

j

œ

J

œ

J

œ

j

œ

Ri - a's on the

.

œ

‰

job,

&

#

œ œ

What cheer

J

œ

œ

R

œ

R

œ

Ri - a? did you

J

œ#

j

œ

J

œ

J

œ

spe - cu - late a

.

œ

J

œ

bob, Oh,

&

#

J

œ

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

Ri - a she's a

œ

J

œ

J

œ

toff, and she

J

œ

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

looks im - men - si -

œ

j

œ

J

œ

koff, And they

&

#

œ

j

œ

j

œ

all shou - ted

œ

œ

"what cheer

J

œ

œ

‰

Ri - a?"

Example 7.7 “Immenseikoff, or The Shoreditch Toff,” chorus,

words and music by Arthur Lloyd (London, 1873).

&4

2

r

œ

Im -

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

≈

r

œ

mense - i - koff, Im -

j

œ

J

œ

J

œ≈

r

œ

mense - i - koff, Be -

j

œ

J

œ

J

œ≈

r

œ

hold in me A

&

j

œ

J

œ

J

œ

≈

r

œ

Shore - ditch Toff, A

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ#

r

œ

j

œ

≈

r

œ

Toff,a Toff,a Toff, A

j

œ

J

œ

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

Shore - ditch Toff, And I

&

J

œ

j

œ

.

J

œ

r

œ

think my - self Im -

j

œ

J

œ

J

œ

‰

mense - i - koff.

was his “donah” ’Arriet and her feathered bonnet. It was she Bernard

Shaw had in mind for Eliza Doolittle when he set about writing Pyg-

malion in 1913: “Caesar and Cleopatra have been driven clean out of

my head,” he remarked, “by a play I want to write for them in which

he shall be a west-end gentleman and she an east-end dona with an

apron and three orange and red ostrich feathers.”

41

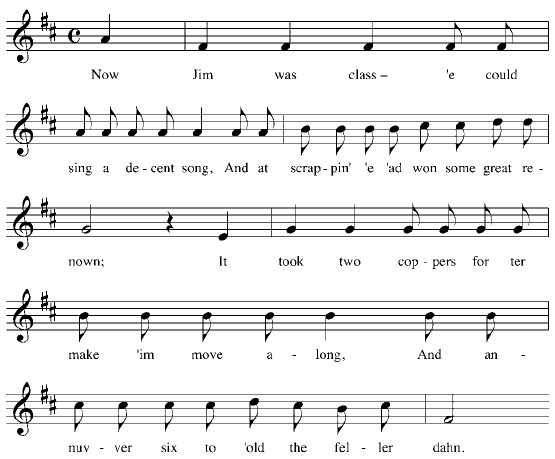

The reflexivity of music hall song is evident in both the title of “Wot

Cher!” (Chevalier/Ingle) of 1891 and, musically, in its use of minor key

verse and relative major key chorus. However, some details of pronun-

ciation have changed: we are given “very,” not the “werry” that was

used in the first verse of Bellwood’s song. “Wot Cher!” enjoyed enor-

mous popularity and helped to establish a jerky dotted rhythm and

leaping melody as standard features of coster songs. The overall effect

can be enhanced with lurching stage movements and cracks in vocal

delivery (see ex. 7.8).

The song was made famous by Albert Chevalier (1861–1923), who

was important to the growing respectability of the halls. The music hall

management were, at this time, concerned to emphasize that men took

their wives to the music hall rather than going there to consort with

“loose women.” The police had become very persistent in looking out

for prostitutes: they even opposed a license to London’s lavish Oxford

Music Hall in 1874 on the grounds that women had been admitted

without men, which they assumed could mean only one thing.

42

May-

hew’s research had shown that costers usually cohabited in an unmar-

ried state, so Chevalier’s coster song “My Old Dutch” (1892) strikes a

blow for respectability.

43

It is a eulogy to forty idyllic years with his wife

(“Dutch” is short for “Duchess of Fife,” Cockney rhyming slang for

“wife”). With his theatrical flair, however, Chevalier raised the emo-

tional temperature of the song, as well as introducing social comment,

by singing it in front of a stage set consisting of the doors to a work-

house, a place that was often a last refuge for many poor elderly couples

and that segregated them by sex. Notice how respectability pervades

the music itself, in the guise of features that would have been associ-

ated with the middle-class drawing room ballad (see ex. 7.9). Similar

repeated quaver chords appear, for example, in the final repeat of the

refrain of Balfe’s “Come into the Garden, Maud” (1857). The song has

untypical harmonic richness, and more attention has been given to the

bass line than is the norm for music hall songs. It has an unusually ac-

tive harmonic rhythm, too, lending it hymn-like associations.

Mrs. Ormiston Chant, the moral crusader outraged by the likes of

Marie Lloyd, recorded visiting a music hall in the “poorest part” of Lon-

don and being moved by the audience’s singing of the chorus to this

song. She thought the emotion it generated “might be a means of in-

troducing into lives a tenderness and a sentiment not hitherto dis-

played.”

44

Unlike the style of “Wot Cher!” however, the refined style of

“My Old Dutch” had no lasting impact on music hall songs. In 1911,

186 Sounds of the Metropolis

Hubert Parry felt able to draw a general comparison between music hall

songs and Cockney speech; they were both, he considered, “the result

of sheer perverse delight in ugly and offensive sound.”

45

Ernest Augustus Elen (1862–1940) was, and still is, often put for-

ward as the “real” to Chevalier’s “sentimental” coster, as the “tough”

and “true to life” character found out on the streets of London. Gus

Elen’s working-class background is often cited approvingly; Chevalier’s

background was lower middle class. Elen had worked as a draper’s as-

sistant, an egg-packer, and a barman, though how much such experi-

The Music Hall Cockney 187

Example 7.8 “Wot Cher!” words by Albert Chevalier, music by

Charles Ingle (his brother) (London, 1891).

188 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 7.9 “My Old Dutch,” excerpt, words by Albert Chevalier,

music by Charles Ingle (his brother) (London,1892).

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

c

c

c

œ

There

œ

œ

œ

Œ

.

œ

J

œ

J

œ

j

œn

J

œ

J

œ

ain't a la - dy liv - in'

œ

œn

Œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

#

œ

œ

Œ œ

œ

Œ

œ œn

œ

j

œ

j

œ

in the land, As I'd

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

n

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œb

œ

œ

œ œn

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

œ

J

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

swop for my dear old

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

˙

J

œ‰œ

Dutch, There

œ

œ

œ

strepitoso

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

.

œ

J

œ

J

œ

j

œn

J

œ

J

œ

ain't a la - dy liv - in'

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

n

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

decresc.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ œn

œ

j

œ

j

œ

in the land, As I'd

œ œn

œ

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ ‰ œ

œb

œ

œ

œ œn

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

œ

J

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

swop for my dear old

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œŒ ‰

œ

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

˙

Dutch.

Ó

Tempo Primo

œ

œ

œ

œ

ences informed his stage persona is impossible to say. He spoke of the

influence of Chevalier when interviewed in the Era (a music hall paper)

in 1905, yet on being asked if he had studied actual costers he replied,

“unconsciously, perhaps.” To point the contrast between Chevalier and

Elen, my next example turns from the lovely wife to the horrid wife.

There is a short film of Elen, late in life, performing “It’s a Great Big

Shame,” a song about a large, burly man who has fallen victim to a tiny,

bullying wife.

46

Elen’s detailed notebook has survived, showing how

carefully he worked out gestures and routines (“Business Make-ups,”

as he called them).

47

Stage movements can, of course, be timed with

precision when accompanied by music. In the Pathé short of 1932, he

reproduces the directions in the notebook. Such a meticulous approach

is not one associated with “being yourself” or “getting into character”

using the Stanislavski method. His movements (the shamble and the

jerk) and his demeanor (the grim and “deadpan” face to suit a tragi-

comic role) point to the kinesic and mimic codes of music hall. His char-

acteristic vocal delivery (little falsetto breaks in the voice before plung-

ing down onto a melody note) also indicates a stylized performance. In

fact, not even these cracks in the voice are left to be improvised; their

precise locations are set down in his notes:

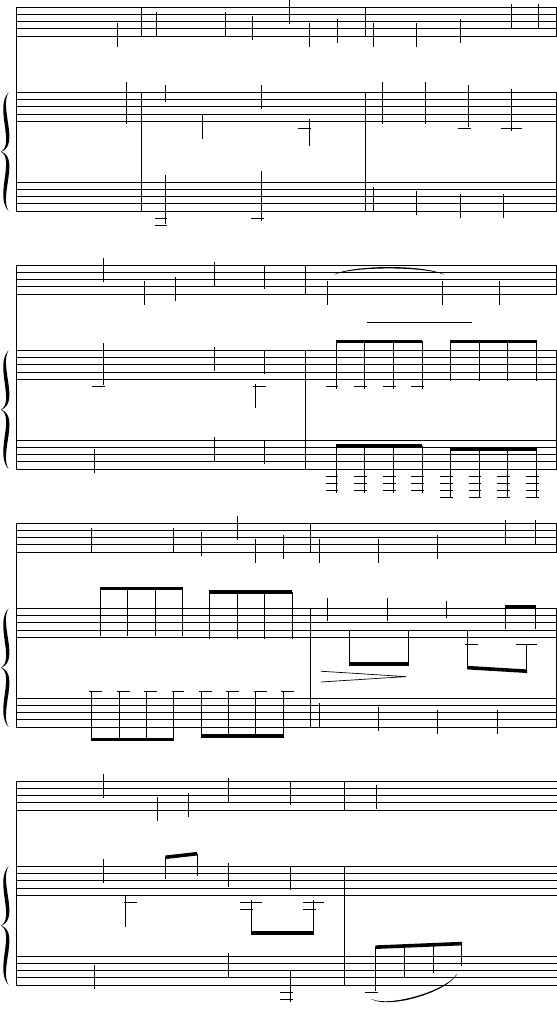

When singing lines—at scrappin’ ’e ’ad won some great

renown.

It took two coppers for to make ’im move along.

And annover six to ’old the feller dow-own.

On word ‘renown’ Jerk this out—latter part of word like

double note

(Re-now-own)—an extra Jerk out word (down)

48

The music to these words is reproduced in ex. 7.10.

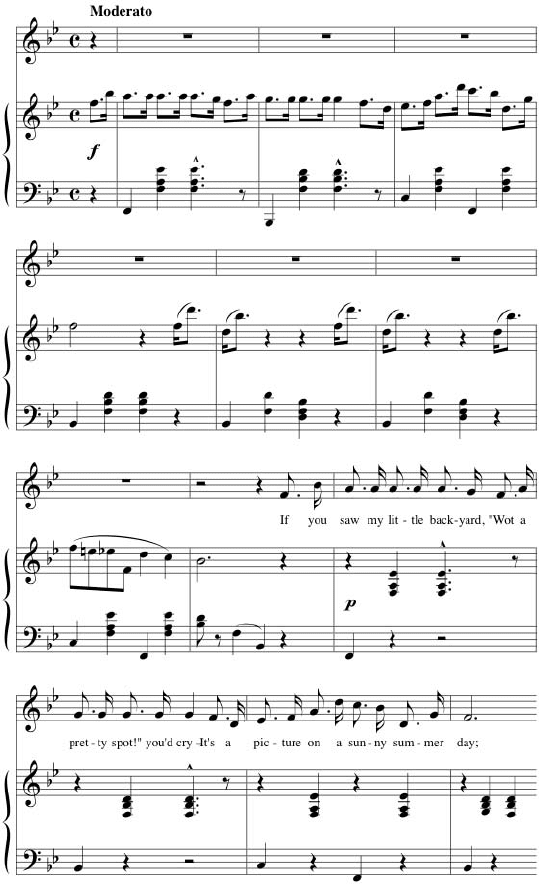

The melodic style developed for Elen by composer George Le

Brunn is designed to enhance such a vocal delivery. The style perme-

ates one of Elen’s best-known songs, “If It Wasn’t for the ’Ouses in Be-

tween” of 1894 (see ex. 7.11).

49

Notice, also, that there is not a plain

“vamp till ready” between verses, but something suggesting an oppor-

tunity for comic stage business.

The musical style would have driven Parry to fury. “Ugly and of-

fensive sounds” begin almost at once: for example, the first measures

of the introduction have the leading note falling to the sixth he hated

so much, a product, as we have seen, of the Viennese popular revolu-

tion. There are also what he would have regarded as crude dissonances

in the second half of measure 3. These two songs show the lyricist

Edgar Bateman introducing features of the “new Cockney” accent that

is found in the work of Andrew W. Tuer (notably, The Kaukneigh Awl-

minek of 1883) and, later, in the work of Bernard Shaw.

50

Both writers

listened to actual Cockneys speaking and, concluding that the Dicken-

sian Cockney had passed away, introduced phonetically a new range of

The Music Hall Cockney 189

sounds—not that this stopped other writers, like George R. Sims and

Somerset Maugham, from continuing in the older vein. Bateman uses

the new f for th in words like “think,” and the new ah for ow. In the

song sheet of “If It Wasn’t for the ’Ouses in Between,” he finds it nec-

essary to add a footnote explaining that “kah” means “cow.” Other fea-

tures of the “new” pronunciation, for example, “down’t” for “don’t,”

“loike” for “like,” “grite” for “great” or Cockney glottal stops in words

like “little” (“li’le”), were not indicated in the song as published, but

then Elen was not restricted to reproducing only the phonetic spellings

provided by Bateman, as his extant recordings demonstrate. For ex-

ample, in “It’s a Great Big Shame,” although Bateman writes “I’ve lost

my pal,” Elen sings “I’ve lorst my pal.” However, he retains the long a

in “great big shame,” in preference to Shavian Cockney, which would

be “gryte big shyme.”

51

An idea of the critical reception of Elen in the 1890s can be ascer-

tained from the typical praising of his performances as “authentic

Cockney,” “true pictures,” and an “ungarnished portrayal of the coster

as he really is.”

52

Sixty years later, the abiding memory of Elen was that

he was “the real thing . . . not an actor impersonating a coster, but a

real coster, or, at any rate, a real Cockney of the poor streets.”

53

For

those who chose to interpret Elen’s stage persona as the real Cockney,

the sign had, to borrow words from Umberto Eco, abolished “the dis-

190 Sounds of the Metropolis

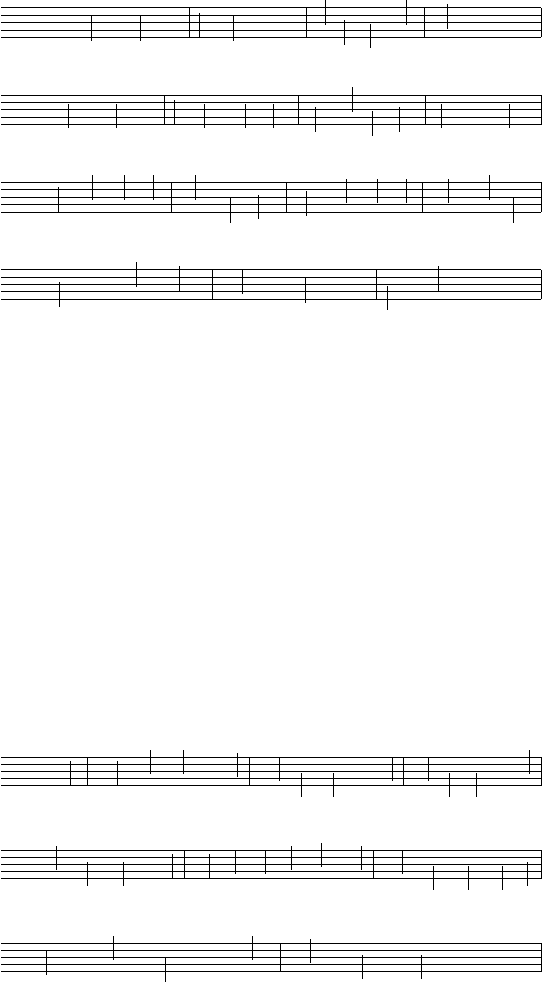

Example 7.10 “It’s a Great Big Shame,” verse 2, excerpt, words by

Edgar Bateman, music by George Le Brunn (London: Francis, Day

and Hunter, 1895).

The Music Hall Cockney 191

Example 7.11 “If It Wasn’t for the ’Ouses in Between,” excerpt,

words by Edgar Bateman, music by George Le Brunn (London:

Francis, Day and Hunter, 1894).