Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Syncopation was being defined even in 1877 as an “abnormal em-

phasis,” but Emmett is aware of this different type of syncopation from

early on.

23

In his dance My First Jig, he cuts short the duration of the

syncopated note (a practice often found later in ragtime piano). Synco-

pation becomes rare in minstrelsy of the 1860s, but returns vigorously

in the 1890s with ragtime and the renewed input of African Americans

into popular music.

Call-and-Response Patterns

Call and response, which has become almost a defining feature of black

music making, is found in songs like Foster’s “De Camptown Races”

and Emmett’s “Dixie’s Land” (exs. 6.5 and 6.8d).

24

152 Sounds of the Metropolis

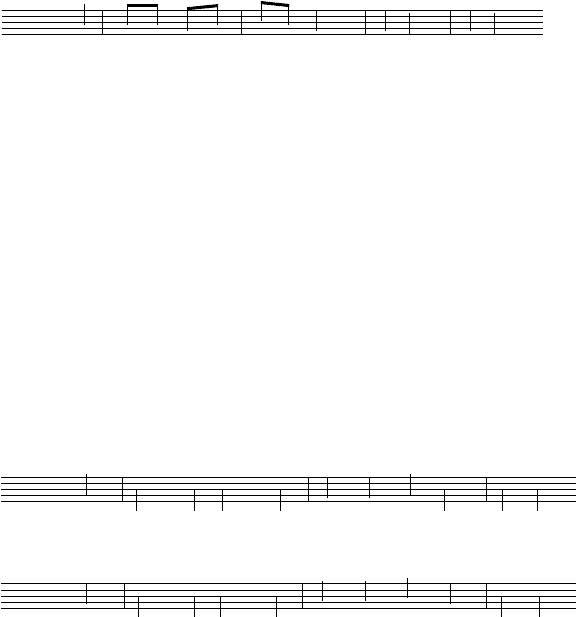

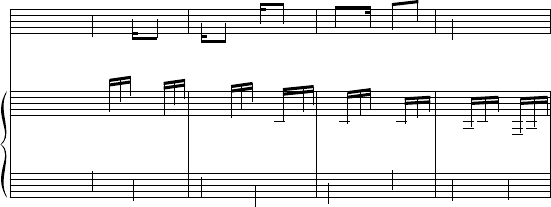

Example 6.5. “De Camptown Races,” words and music Stephen

Foster (Baltimore: Benteen, 1850).

&

#

#

4

2

Moderato

j

œ

soloist

De

œ œ

œ

œ

Camp town la dies

œ

œ

j

œ

‰

sing dis song

j

œ

chorus

.

œ

Doo dah!

j

œ

œ

Doo dah!-- - -

Pentatonic Shapes

Although these shapes are insufficient in themselves to enable us to

verify anything, they become significant as an African-American fea-

ture once they are recognized as forming part of a chain of other sig-

nifiers of black music making (ex. 6.6a). Example 6.6b provides, for

purposes of comparison, alternative pitches typical of a nineteenth-

century European popular style for the words “I hear de noise den saw

de fight” in “Old Dan Tucker.”

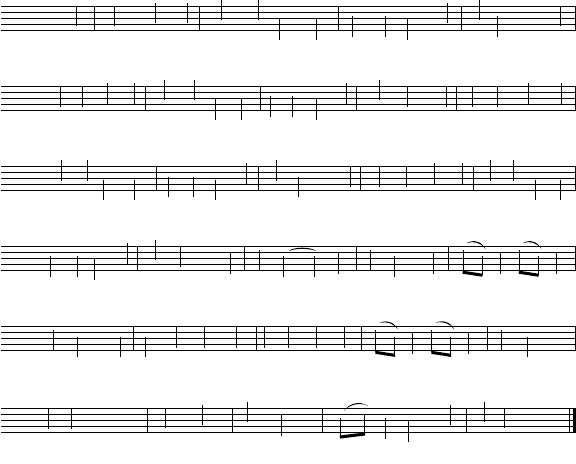

Example 6.6 (a) “Old Dan Tucker,” original pentatonic form; (b) a more

typical nineteenth-century European popular tune shape.

&

b

b

4

2

j

œ

I

.

J

œ

R

œ

.

J

œ

R

œ

hear de noise den

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

J

œ

saw de fight, De

J

œ

J

œ

watch-man

&

b

b

j

œ

I

.

J

œ

R

œ

.

J

œ

R

œ

hear de noise den

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

saw de fight, De

J

œ

J

œ

watch - man

(a)

(b)

The Important Role of Dance

Some songs were danced and sung simultaneously, and almost all songs

incorporated bodily movement, if not what might be described strictly

as dance.

The Texts

Song lyrics can sometimes be linked to African cultural interests, for ex-

ample, animal fables or trickster humor. Rice’s “Jim Crow,” which was

taken, as mentioned earlier, from a black street performer, seems Euro-

pean in musical style; yet the lyrics appear indebted to the Yoruba trick-

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 153

Ambiguous Thirds and Flattened Sevenths

These are sometimes present in a way that prompts parallels to be made

with the “blue notes” of jazz. Hans Nathan finds that “My Old Aunt

Sally” resembles in parts Charles Dibdin’s “Peggy Perkins”;

25

but surely

the most striking feature in the former is the use of flattened sevenths

in the refrain (see ex. 6.7). Henry Russell retains these when he varies

the tune for his song “De Merry Shoe Black.”

26

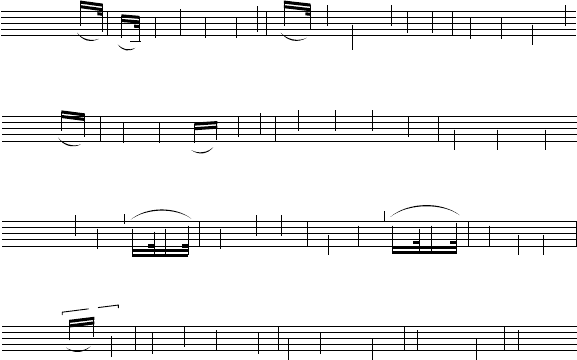

Example 6.7 “My Old Aunt Sally,” as published in Davidson’s Cheap

Edition of the Songs of the Ethiopian Serenaders (London, c. 1848).

&

b

8

6

j

œ

A-

.

œ

œ

j

œ

way down in

œ

j

œ

œ

J

œ

New Or-leans, I

œ

J

œ

œ

j

œ

gets up-on de

j

œ

œ

Œ

j

œ

lan-din', And

&

b

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

dere I spies my

œ

j

œ

œ

J

œ

old Aunt Sal, up -

œ

J

œ

œ

j

œ

on de track a

j

œ

œ

Œ

j

œ

stand-in'; I

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

ax her, 'Won't you

&

b

œ

j

œ

œ

J

œ

take a ride wid

œ

J

œ

œ

j

œ

me, dis cot-ton

j

œ

œ

Œ

j

œ

sea-son';– I

œ

j

œ

œ

j

œ

neb- ber spoke a -

œ

j

œ

œ

J

œ

no-der word, a -

&

b

œ

J

œ

œ

j

œ

cos I had no

j

œ

œ

Œ

J

œ

rea-son; No

J

œb

œ œ

J

œ

rea-son, no

J

œb

œ

Œ

J

œ

rea-son, A -

œb

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

cos I had no

&

b

J

œb

œ

Œ

J

œ

rea-son; I

œ

J

œ œ

J

œ

neb - ber spoke an -

œ

J

œ œ

J

œ

o - der word, A -

œb

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

cos I had no

J

œb

œ

Œ‰

rea-son–

&

b

J

œ œ

Œ‰

Sal-ly!

.

œ

.

œ

Ra, ree,

.

œ

.

œ

ri, ro,

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

j

œ

round de cor - ner,

j

œ

œ

Œ

Sal-ly.

ster, who was a crow. The character of Jim Crow established the ragged,

raucous joker stereotype of the minstrel show.

(Second verse)

I us’d to take him fiddle

Ebry morn and arternoon,

And charm de old buzzard,

And dance to the racoon.

(Refrain)

Wheel about, and turn about, and do jis so,

Ebry time I wheel about, I jump Jim Crow.

According to William Mahar, even the dialect used in minstrelsy

approaches, at times, “period attestations of spoken dialect.”

27

The di-

alect was, however, always going to be compromised, since it had to be

recognizable and understood by a white audience while at the same

time signifying difference and a black Other.

The fusion of styles in minstrel songs was effected from a variety of di-

rections (America, Africa, Europe) and by people of varying social and

cultural backgrounds. Henry Russell, for example, was Jewish, and

George Dixon, whose song “Zip Coon” established the black dandy

stereotype, was of black and white parentage.

28

Thus, the songs are too

fluid to be dissected analytically so as to reveal conclusively the prove-

nance of their constituent parts. Black musicians on southern planta-

tions were accommodating European music to their own aesthetic de-

mands, just as white musicians were reworking plantation songs and

dances to suit themselves. For instance, there were claims that Dan

Emmett’s “Dixie’s Land” was based on a southern African-American air

“If I Had a Donkey,” but if so, then that song must itself have been

based on Henry Bishop’s “Dashing White Sergeant,” to which “Dixie’s

Land” bears clear resemblances (see ex. 6.8).

29

This cultural “to-ing and fro-ing” does not mean that the question

of cultural appropriation may be ignored but, rather, that it should be

seen as a matter of unequal power relations in the social domain rather

than as an abstracted question of musical aesthetics. The white musi-

cian was able to define the nature of black music and dominate its re-

ception, leaving the black musician with an identity at odds with his or

her subjectivity. Thus, one consequence of whites’ power to define

black culture was that African Americans were left dispossessed of a

means of representing themselves on stage, and this was to last a long

time—even Louis Armstrong was never able to shake himself entirely

free of minstrel gestures.

In England, minstrels quickly lost the raucousness and challenging

of dominant moral values found in their early American context. As

the 1850s wore on, instead of wanting to bet money on the horses at

154 Sounds of the Metropolis

the Camptown racetrack, they were content to dream about what it

might be like to be a daisy.

30

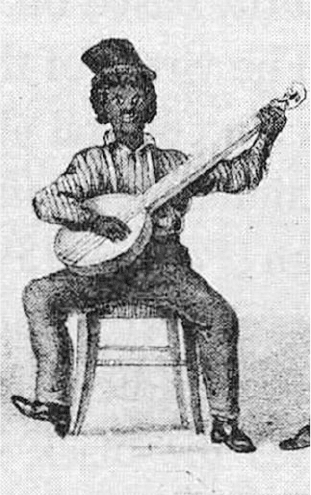

They were also tending to sit with their

legs together, and the banjo was not displayed in such an obviously

phallic manner as it had been (see fig. 6.3).

However, even in America, the catastrophe of the Civil War was to

dampen the minstrels’ high spirits. As the songs were increasingly taken

over by sentiment after 1860, mothers became popular figures. Here

are half a dozen sample titles:

“Mother I’ll Come Home Tonight”

“Mother Kissed Me in My Dream”

“I’m Lonely since My Mother Died”

“Who Will Care for Mother Now”

“Let Me Kiss Him for His Mother”

“Dear Mother, I’ve Come Home to Die”

The mother fixation was to linger on into the twentieth century in Al

Jolson’s impassioned appeals to his mammy.

London became a center of minstrel sheet music production to

equal New York. Hopwood and Crew advertised themselves as “Pub-

lishers of the Whole of the Songs and Ballads, sung by the ORIGINAL

CHRISTY MINSTRELS”—by which they referred not to the original

troupe organized by E. P. Christy, but to the troupe under the propri-

etorship of Moore and Burgess at St. James’s Hall, Piccadilly. Many of

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 155

Example 6.8 (a) “The Dashing White Sergeant,” from the opera The Lord

of the Manor, by Henry Bishop (London: Goulding and D’Almaine, 1812);

(b) “Dixie’s Land,” by Dan Emmett (New York: Firth, Pond, 1860);

(c) “The Dashing White Sergeant”; (d) “Dixie’s Land.”

&

#

#

œ

œ

I

j

œ

j

œœ

œ

r

œ

r

œ

wish I was in de

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

land ob cot - ton,

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

Cim - mon seed

&

#

#

4

2

.

œ

œ

If

.

œ

œ

.

r

œ

r

K

œ

j

œ

.

r

œ

r

K

œ

I had a beau, For a

.

œ

œ#

.

r

œ

R

Ô

œ

j

œ

R

œ

R

œ

sol - dier who'd go, Do you

R

œ

R

œ

J

œ

j

œ

think I'd say no?

&

#

#

j

œ

J

œ

r

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

march a-way,

J

œ

j

œ œ

march a - way,

J

œ

J

œ

r

œ

.

œ

œ#

.

œ

œ

march a-way,

J

œ

J

œ œ

march a - way,

&

#

#

3

œ

œ

R

œ

Den I

J

œ

J

œ

.

J

œ

R

œ

wish I was in

J

œ

œ

J

œ

(Chorus)

Di - xie, Hoo -

.

œ

J

œ

ray, Hoo -

.

œ

ray,

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

the songs were also being published in Charles Sheard’s Musical Bouquet

series. Most of Stephen Foster’s songs, too, were published in the Musi-

cal Bouquet. A cheaper publisher, Davidson, was selling “Negro Songs”

at threepence each in his series the Musical Treasury, which he styled

“the original and only genuine music for the million.” It is not surpris-

ing that minstrel songs, being often of vague provenance, led to battles

over rights between publishers.

Hopwood and Crew knew that the middle-class market for their

music hall songs was limited, but not that for their minstrel songs,

which they proclaimed “have taken such a permanent hold in the es-

teem of the musical public, ever welcomed and highly appreciated in

the drawing room, and the greatest favourites with teachers in Class In-

struction.”

31

One attraction was the ease with which many minstrel

songs (especially of the early variety) could be sight-read at soirées,

should an unfamiliar one be placed in front of the accompanist. As a

character remarks in Bernard Shaw’s novel The Irrational Knot, “you

need only play these three chords. When one sounds wrong, play an-

other.”

32

Thus were the pleasures of a three-chord aesthetic indulged in

well before the days of punk rock. The songs were also taken up by the

Tonic Sol-fa Agency and published in Sol-fa notation for singing classes

and choirs. With the passing of time, the harmonies of some songs be-

came more sophisticated and employed passing modulations, as found

in “Annie Lisle” (see ex. 6.9), a song Hopwood and Crew advertised as

156 Sounds of the Metropolis

Figure 6.3 The Virginia Serenaders’

banjoist, J. P. Carter, in blackface.

one of the songs “sung with the greatest success by the Christy Min-

strels’ eminent Tenor, Mr J. Rawlinson at St. James’s Hall.”

33

There is

unmistakable evidence in such advertisements of the British embour-

geoisement of American minstrelsy.

England’s Preeminent Minstrel Troupes

The Reverend Hugh Haweis called the Moore and Burgess Minstrels

the “princes of the art,” but continued, “From St. James’s Hall, and not

from ‘Old Virginny,’ come constant supplies of new melodies. The orig-

inal melodies, such as ‘Lucy Neal,’ ‘Uncle Ned,’ some of which were no

doubt genuine American Negro productions, are almost forgotten.”

34

His comment reveals that the production of minstrel songs was in full

swing in England in the 1860s and 1870s.

The smaller of the two halls inside what was referred to in singular

fashion as St. James’s Hall (Piccadilly) was a home of minstrelsy from

1859 to 1904. The Moore and Burgess (originally Moore and Crocker)

Minstrels began their long residency there on 16 September 1865. It

lasted the rest of the century, by which time the troupe was sixty

strong. They advertised their shows as suitable for families.

35

Even the

clergy frequented the smaller St. James’s Hall with enthusiasm. Harry

Reynolds reports it being said that “this was the only entertainment

Catholic priests were allowed to attend.”

36

Charles Dodd, a respectable

head teacher from Wrexham who would stay only in temperance ho-

tels, remarks of his visit with friends in 1878: “With the entertainment

we are delighted. We hear some grand music, both vocal and instru-

mental, conundrums, speeches, etc.”

37

An anonymous reviewer toward

the end of the century, looking back at the troupe’s many years of suc-

cess, comments: “It has always been the aim of the conductors of the

Moore & Burgess Minstrels to give an entertainment at which no sen-

sible person can take offence.”

38

When George Washington Moore (a

principal performer and one of the resident troupe’s proprietors) per-

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 157

Example 6.9 “Annie Lisle,” words and music by H. S. Thompson

(Boston: Oliver Ditson, 1857), beginning of the refrain.

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

4

2

4

2

4

2

Moderato

œ

œ

.

œ

Wave willows,

≈

œ

œ

œ

≈

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

‰

J

œ

‰

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

mur mur wa ters,

≈

œ

œ

œ≈

œ

œ#

œ

J

œ

‰

J

œ‰

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

Gol den sunbeams

≈

œ

œ

œ

≈

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

‰

j

œ

‰

˙

smile,

≈

œ

œ

œ

≈

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

‰j

œ

‰

--- -

formed in blackface, it was without the grotesqueness found in many

of the American burnt cork caricatures (fig. 6.4). The makeup had orig-

inally been of a crude variety: corks were simply soaked in alcohol, set

on fire, and then mixed with water into a paste.

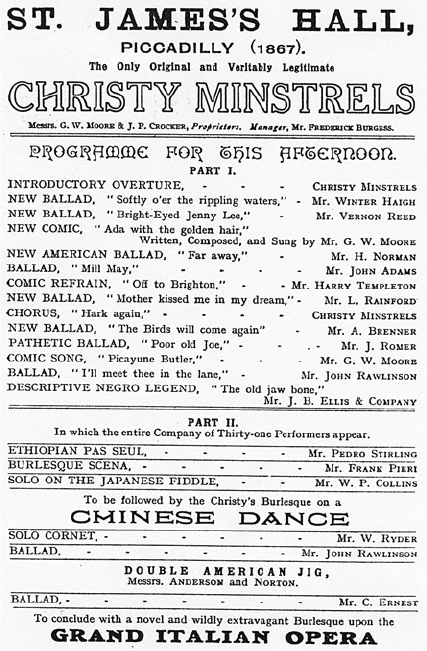

The Moore and Crocker (soon to be Moore and Burgess) Christy

Minstrels program for an unspecified afternoon in 1867 shows the two

contrasting halves of a typical entertainment (fig. 6.5).

39

Ballads and

comic songs fill most of the first half, which concludes with a narrative,

“The Old Jaw Bone,” which probably included “stump speech” conven-

tions. The second half is dominated by parody and burlesque. The

Japanese fiddle may refer to a one-string instrument—such was the

“Japanese fiddle” on which the Cockney blackface performer G. H.

Chirgwin played with much skill later in the century.

40

The show con-

cludes with an opera burlesque. Arthur Sullivan hit back at their fond-

ness for burlesquing opera when he included a parody of their music

making in the ensemble piece “Society has quite forsaken” in act 2 of

Utopia Limited (1893). The troupe was large by 1867 standards, having

thirty-one members.

As an example of their satirical humor, let us examine “The Gre-

cian Bend,” written, composed, and sung by George Moore. In the

1860s, it became fashionable to bunch skirts at the back into panniers

158 Sounds of the Metropolis

Figure 6.4 George Moore.

worn below the waist; the bustle was then developed to fill the gap be-

tween panniers and lower back. Understandably, women needed to

bend forward to keep their balance, and the posture was dubbed the

“Grecian bend.”

41

This furnished ample excuse for a topical satire that

would appeal across classes. Middle-class families must have bought

the song because the sheet music was expensively produced, having a

lithograph on the title page in which the green color of a slim umbrella

was skillfully registered without blotches at a time when lithographic

stones were still being used. It retailed at 3 shillings (fig. 6.6).

I am sure affluent, fashion-conscious women laughed at the song,

as no doubt in more recent times lovers of designer clothes have laughed

at the fashion excesses of Patsy and Edwina on the television comedy

series Absolutely Fabulous. The dance interlude is a Schottische, which

might seem bizarre but for the knowledge that style mixing was never

something that unduly bothered blackface minstrels.

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 159

Figure 6.5 Program for the Christy Minstrels.

The Grecian bend now go it ladies,

Shake yourselves and set us crazy,

Double up, and show the men,

The style is now the Grecian bend.

The Mohawk Minstrels were England’s other celebrated troupe.

They were formed by James and William Francis (who worked for the

music publisher Chappell) to rival the Moore and Crocker Minstrels.

After first working semiprofessionally, they moved into Berners Hall in

1873, next to the Agricultural Hall in Islington. They soon had rivals

themselves in the Manhattan Minstrels, but they determinedly ap-

proached the leader of that troupe, Harry Hunter (1840–1906), and

made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. He was already an accomplished

actor, singer, and sketch writer. The Mohawks now became so success-

ful they moved to the nearby St. Mary’s Hall, which held 3,000. Since

so much of the troupe’s material was original, the Francis brothers got

160 Sounds of the Metropolis

Figure 6.6 “The Grecian Bend,” title page lithograph.

together with David Day of Hopwood and Crew to form a new publish-

ing company. Later they were joined by Hunter himself to become the

huge and successful music business Francis, Day and Hunter. The firm

also sold minstrel requisites, such as plain wigs at 2 shillings and six-

pence and “eccentric” wigs for a shilling more.

The Mohawks included some fine singers, and an unusual feature

of their accompanying instrumental ensemble was that it included a

harp. For a while, they employed a black artist, Billy Banks, who had

come to England with Callender’s Colored Minstrels. Unfortunately, he

died after having been with them one year only. In the 1890s, George

D’Albert won plaudits as their female impersonator; he was a fine

dancer with an excellent falsetto voice. To add to the many contradic-

tions of minstrelsy, a great many of his most fervent admirers were

women. In 1900, Francis and Hunter took over the St. James’s Hall

lease and created the Mohawk, Moore and Burgess Minstrels. Admir-

ers of both troupes were dissatisfied, however, and business was un-

healthy. In 1904, minstrelsy at St. James’s Hall came to an end, and

Harry Hunter died two years later.

42

The Mohawk Minstrels’ “Grand New Programme,” (reproduced in

fig. 6.7) follows the norm of two contrasting halves. Minstrel troupes

sat in a semicircle with Tambo at one end and Bones at the other. These

corner men, or end men, were the comedians. The emcee came to

be known as the Interlocutor, since he was frequently asking the cor-

ner men questions. Perhaps the most famous of minstrel jokes runs as

follows:

Corner man: “My dog’s got no nose.”

Interlocutor: “How does he smell?”

Corner man: “Awful!”

Harry Hunter played Tambo when he joined the Mohawks, but be-

came the Interlocutor, a role he plays here, punctuating a succession of

ballads and comic songs until the cast comes together for a “Japaneasy

Absurdity” before the interval. The second half looks a little like a va-

riety show, minus the performing dogs and acrobats, but note that it

contains a selection from Balfe’s Bohemian Girl.

The Mohawks’ satirical songs could have at times an acerbic qual-

ity, even a political character, as illustrated by Hunter’s “Because He

Was a Nob”:

There was a man, a nobleman,

A nob of high degree,

But he knew how to work it, though

No working man was he;

For though there might be thousands out,

And looking for a job,

He had a job brought thousands in,

Because he was a nob.

43

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 161