Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

its “sehr hübsche Motive” (very pretty themes) and had no doubt that

it would be reckoned one of the season’s best dance compositions.

74

In confirmation of its enduring melodic appeal, a tune from this waltz

(added to one from Vermählungs-Toaste, op. 136) was used for the duet

“Warm” in the film musical The Great Waltz (MGM, 1972).

Strauss Jr. enriched the waltz in terms of harmony and timbre (his

orchestra swelled in size to around fifty, because he absorbed his fa-

ther’s players after his father’s death), and he composed melodies that

outlasted his father’s in memorability. Strauss Jr. was responsible for

the Verzückungswalzer, which exercised a seductive charm with its

rhythm and harmony (Verzückung is a state of ecstasy). In an instance

of popular art influencing “high” art, it had an influence on Wagner’s

music for the Flower Maidens in Parsifal. Perhaps Strauss Jr. in the mid-

1860s stands in the same relationship to his father’s music as, a century

later, the Beatles and “Strawberry Fields” did with respect to Elvis Pres-

ley and “Jailhouse Rock.” There is more obvious artistry and refine-

ment, but there is also something earthy and spontaneous (or could the

word be “electric”) that has been lost. Early rock ’n’ roll was very defi-

nitely intended to be danced to, just as were the waltzes of Lanner and

Strauss Sr., but the “art rock” that developed in the 1960s had the same

dual character as the “symphonic waltzes” of the 1860s. Public esteem

may be carried along with such developments, though it often turns

against them (especially if pretentiousness is suspected).

Excursions into the domain of high art notwithstanding, the serious

music art world continued to cold-shoulder Strauss. When his music

was heard in the grand surroundings of the recently opened Goldener

Saal of the Musikverein, 13 March 1870, some critics thought it inap-

propriate for this high cultural venue. The concert’s success, however,

led to thirty more years of Sunday afternoon concerts. In the fiftieth

anniversary year of his debut concert at Dommayer’s Casino, Strauss

was made an honorary member of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde,

and was thereby accorded recognition as a composer of status, albeit a

mere five years before his death. As for Johann’s youngest brother, Ed-

uard, who survived into the twentieth century, he remains a neglected

figure, though he produced over 300 compositions and enjoyed a big

success in London in 1885. He became conductor of the Strauss Or-

chestra after Josef’s death in 1870 (having already been its conductor

during Johann’s and Josef’s absences in Russia), and after Strauss Jr.

was relieved of his duties as Hoffball-Musikdirektor because of ill health

in 1871, Eduard took over the following year. He disbanded the Strauss

Orchestra in 1901.

Today, millions watch the New Year’s Day concert from Vienna on

television, imagining that the link between the Vienna Philharmonic

Orchestra and the music of the Strauss family is lost in the mists of

time. In fact, the Wiener Philharmoniker was reluctant to play this type

of music in the nineteenth century, and when the orchestra did so on

142 Sounds of the Metropolis

14 October 1894, it was intended as a special honor to Johann Strauss

as part of the fiftieth-anniversary celebrations of his debut. Many more

years were to elapse before the New Year concerts at the Musikverein

were established; the very first of these was conducted by Clemens

Krauss during wartime in 1941.

A Revolution on the Dance Floor, a Revolution in Musical Style 143

6

Blackface Minstrels,

Black Minstrels, and

Their European

Reception

144

African Americans and their cultural practices were first seen through

the distorting medium of blackface performance, which began when

New Yorker Thomas Rice copied his “Jim Crow” dance routine from an

African-American street performer, and introduced it into his act at the

Bowery Theatre, 12 November 1832.

1

Charles Hamm remarks that the

minstrel song “emerged as the first distinctly American genre.”

2

Rice

visited London in 1836. The first troupe, the Virginia Minstrels (fiddle,

banjo, tambourine, and bone castanets) formed in New York in 1842,

calling themselves minstrels after the recent success enjoyed by the Ty-

rolese Minstrel Family. Stephen Foster (1826–64), who composed for

E. P. Christy, another pioneering troupe, had helped to win approval for

the genre. He boasted, “I find that by my efforts I have done a great deal

to build up a taste for the Ethiopian songs among refined people.”

3

His

first big success, “Oh! Susanna,” was published in New York in 1848.

“Massa’s in de Cold Ground” and “My Old Kentucky Home, Good

Night,” published in New York in 1852 and 1853, respectively, were

both labeled “plantation melodies,” though the words of the former are

in minstrel dialect and those of the other are not. Visitors to America

sometimes mistook Foster’s songs and other blackface minstrel songs

for African-American songs. Moritz Busch collected and published some

of them as Negro songs in Wanderungen zwischen Hudson und Mississippi,

1851 und 1852;

4

they included “O Sussianna” (“Oh! Susanna”) and “The

Yellow Rose of Texas,” which became “Gelbe Röslein von Indiana.”

5

Minstrelsy overshadowed the achievements of black composers in the

1840s, such as the dance-band leader Frank Johnson.

6

The conditions for the British reception of blackface minstrelsy, an

entertainment purporting to depict the recreational activities of black

plantation slaves, differed in various respects from those in America,

and for historic reasons. Slavery had been illegal in Britain since 1772,

and after the campaigning efforts of William Wilberforce and others,

the slave trade had been abolished in 1807. Those opposed to abolition

had failed in their arguments that black slaves led happy and contented

lives on American plantations and that their Christian masters were

striving to save the souls of heathens. Another issue that forced the re-

consideration of slaving interests was that Britain, at that time, was

having to define its understanding of freedom in the wake of the revo-

lutionary interpretation of la liberté in France and the circulation of

French political ideas in Britain. This was fueled by the founding of rad-

ical groups like the London Corresponding Society and the appearance

of publications such as Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man (1791–2) and Mary

Wollstonecroft’s Vindication of the Rights of Men (1790), in which she

condemned the slave trade—“a traffic that outrages every suggestion of

reason and religion.”

7

Slavery was eventually abolished throughout the

whole British Empire in 1833. Later in that decade, radicalism was

reawakened by the Chartist movement, which associated freedom with

the right to vote. In 1843, the year the Virginia Minstrels, the first es-

tablished blackface troupe, visited Britain, the leader of the London

Chartists was William Cuffey, the grandson of an African slave.

The reaction to the early minstrel troupes in the 1840s, then, was

not one of uniform praise throughout England, and often entailed some

unease, especially in the industrial Northwest. To win approval, black-

face performers stressed the wholesomeness of their entertainment and

their personal respectability. This had been true of the pioneering solo

blackface performer Thomas Rice, whose visit in 1836, according to the

London Satirist, spread a “Jim Crow” mania though “all classes.”

8

Ten

years later, the Ethiopian Serenaders made their first London appear-

ance at the prestigious Hanover Square Rooms, charging hefty prices of

2 and 3 shillings for tickets. Their status was assured when they were

invited to perform before Queen Victoria. From then on, although it

was true that blackface minstrels did appeal to British working-class

audiences, in Britain they always had a bourgeois audience more firmly

in their sights, and thus left available a cultural space that was to be

filled by the music hall. In contrast, minstrelsy remained the most pop-

ular form of urban working-class entertainment in America until the

rise of vaudeville in the 1880s—though, ironically, vaudeville came

about as a deliberate attempt to attract the “middling class” into theatres.

I do not wish to give the impression that minstrelsy automatically

endorsed slavery. There are, indeed, antislavery minstrel songs, for ex-

ample, by Henry Russell and, later, Henry Clay Work. In New York, the

Hutchinson Family sang their abolitionist song “Get off the Track” to

the tune of “Old Dan Tucker,” one of the Virginia Minstrels’ biggest

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 145

hits.

9

Many minstrel troupes were also quick to incorporate scenes

from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s highly successful novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin

(1852). The primary purpose of the blackface mask was to signify a par-

ticular theatrical experience, and to allow performers to behave on stage

in a way that would not normally be condoned.

10

Blackface minstrels

were double coded, inscribing racism, but at the same time subverting

bourgeois values by celebrating idleness and mischief rather than work

and responsible behavior. An example of how the blackface mask pro-

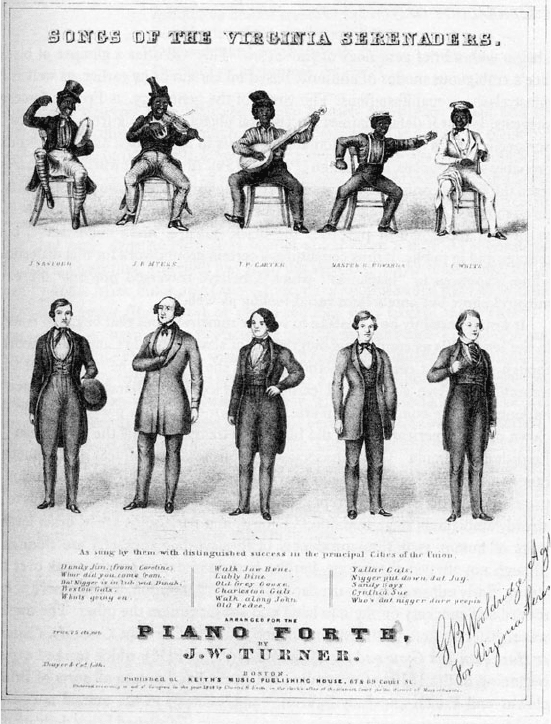

duces a character transformation on the Virginia Serenaders can be seen

on the front cover of a collection of their songs (see fig. 6.1).

Such humor works on its own terms and requires no knowledge of

African-American behavior—and just as well, because most Europeans

146 Sounds of the Metropolis

Figure 6.1 The Virginia Serenaders.

had none. The unruly humor may explain why minstrelsy appealed to

British audiences, providing them with a release of tension in an age of

social restraint and inhibition. The influence on British society of those

campaigning on behalf of black emancipation had declined by the middle

of the century, though slavery remained an issue of public interest until

the 1870s.

11

British minstrels retained their cross-class appeal in these

succeeding years, borrowing from music hall on occasion, but always

selling themselves to the middle class as wholesome entertainment and

displaying a more eloquent wit in their burlesques and comic songs than

that found in the music hall. Even British banjos began to differ from

those in America, with the development of five- and six-string models

as well as the zither banjo. That said, it is highly likely that minstrelsy in

Britain encouraged the acceptance of imperialist ideology by depicting

emotional and hyperactive blackface characters who needed to be kept

in check by a firm but fair Mr. Interlocutor. It easy to see how this could

extend to the idea that a colonial presence was required to ensure a pa-

ternalistic regulation of conduct in countries overseas.

The Virginia Minstrels commenced their English tour at the Con-

cert Rooms, Concert Street, Liverpool, on 21 May 1843. They sang in

solo or unison, and accompanied themselves on fiddle, banjo, tam-

bourine and bone castanets (made of cow ribs).

12

They were not par-

ticularly successful in Liverpool, but earned enough to travel to Man-

chester, where they appeared in the upmarket Athenaeum Rooms.

There was hardly an enthusiastic response from the Manchester critics;

one wrote, “As a specimen of Negro holiday enjoyment, the entertain-

ment is worth seeing once.”

13

The Virginia Minstrels were finally given

a warm critical reception when they appeared at the Adelphi Theatre,

London, in June 1843, for a fee, the manager claimed, of £100 a week.

Manchester remained unconvinced about minstrelsy; when the Ethi-

opian Delineators arrived in 1846, the Manchester Guardian advised its

readers, “The Ethiopian Delineators are amusing enough to hear and

see once.”

14

Remarkably, when the Ethiopian Serenaders performed to

a rather empty Free Trade Hall later that year, the press handed out ac-

colades. Fresh from their London success, they sang in harmony, wore

concert dress, and did not dance. They were six strong, favored songs

of a sentimental hue, and accompanied them with two banjos, accor-

dion, guitar, tambourine, and bones. A song they sang that became

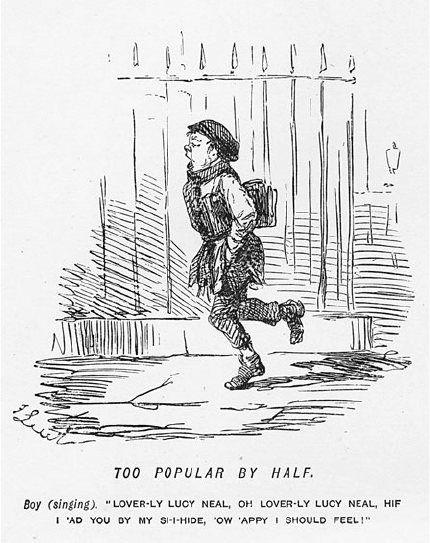

a great favorite in England (see fig. 6.2) was “Lucy Neal,” which re-

inforced antislavery feelings with its tale of enforced separation and

heartbreak on the plantation.

15

(Final verse)

Dey bore her from my bosom, but de wound dey cannot heal;

And my heart, my heart is breaking, for I lub’d sweet Lucy Neal.

O! yes and when I’m dying, and dark visions round me steal,

De last low murmur ob dis life shall be, sweet Lucy Neal.

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 147

(Refrain)

O! poor Lucy Neal, O! poor Lucy Neal!

If I had you by my side, how happy I should feel!

The year after the visit of the Ethiopian Serenaders, the Manchester

Guardian returned to berating minstrelsy, calling the songs “musical

abortions.”

16

They were not alone; the Manchester Courier, having wit-

nessed the New Orleans Serenaders at the Free Trade Hall, declared,

“one exhibition of the kind is quite sufficient in one generation.”

17

The

general tenor of these quotations does make evident, however, that the

citizens of Manchester had no objection to trying out anything once.

Interestingly, Manchester, renowned for its freethinking and radical-

ism, received a visit from a seven-strong troupe, the Female American

Serenaders, in 1847, a time when female minstrels do not seem to have

performed publicly in America. The Manchester Guardian, with charac-

teristic distaste, described their performance as a “questionable enter-

tainment.”

18

The attitude of the Manchester press could easily be inter-

preted as defensiveness in the face of a new kind of popular music. One

148 Sounds of the Metropolis

Figure 6.2 “Too Popular by Half” (1847), cartoon

by John Leech, in John Leech’s Pictures of Life and

Character from the Collection of “Mr. Punch” (London:

Bradbury, Agnew, 1886), 250.

remembers that it was in Manchester’s Free Trade Hall that Bob Dylan

was booed for picking up an electric guitar.

Seeking the Black beneath the Blackface

Hans Nathan and other scholars have shown that early minstrel songs

often bear a kinship to English theatre music and Irish and Scottish

dance music, but it is a more difficult matter—particularly in the ab-

sence of contemporary documentation—to demonstrate African influ-

ence. However, it seems highly likely that minstrelsy in the 1840s was

a fusion of black and white cultural elements. After all, would the early

minstrels be so keen to copy the instruments of plantation music mak-

ing

19

but not the actual music those instruments played? Among what

strike me as black elements are the following ten features.

The Constant Pulse

This was usually emphasized by the banjoist tapping his heel. If playing

solo in, say, a circus, a banjoist would stand on a small wooden plat-

form to help the taps resonate, thus showing it was considered an im-

portant percussive feature and not merely a crude means of keeping

time. This steady background pulse, with which the rhythmic fore-

ground interacts, is important to syncopation and polyrhythmic de-

vices. It also encourages the omission of notes on strong beats and

prompts, instead, the playing of accented offbeat notes. Heel tapping is

absent from the sheet music, of course—with the exception of the op-

eratic parody song “Stop Dat Knocking,” which at one point refers jok-

ingly to a “Solo wid de heel.”

20

The Drone

The banjo has an inverted drone (on the dominant in the nineteenth

century); it is the highest string, but positioned to be played by the

thumb. It affects harmonies and creates clashes that were unfamiliar in

European music of that time. Joel Sweeney, who is often given credit

for adding the fifth string to the banjo, added an extra low string, not

this short drone string (as is sometimes assumed).

The Use of Slides

These are not common in European playing practices, especially when

accented, and their effect would be more pronounced on older nonfret-

ted banjos. (Henry Dobson is credited with being the first to add frets,

around 1878.)

Motivic Structure

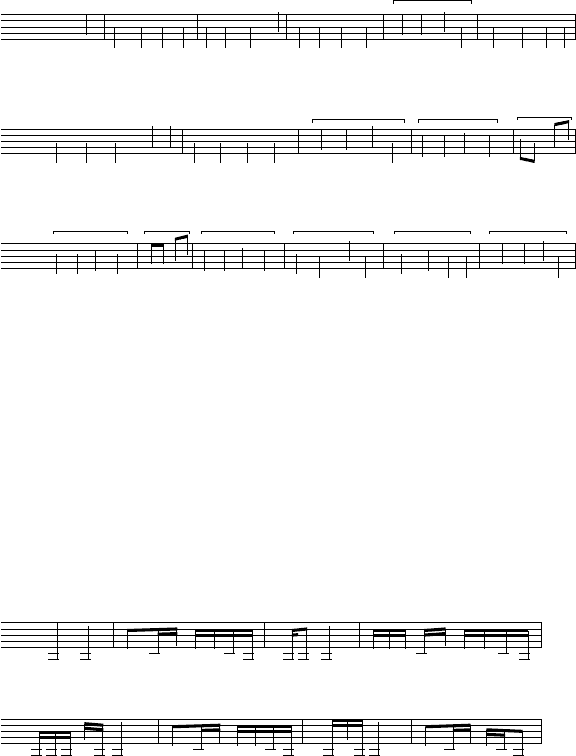

Many of the early songs are dominated by repeated motives. An ex-

ample is “Old Dan Tucker” (which Emmett claimed as his own compo-

sition, though evidence suggests otherwise). One of the most popular

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 149

songs in the Virginia Minstrels’ repertoire, it contributes a musical new-

ness to complement the newness of dance and words that had already

been established with “Jim Crow” (ex. 6.1).

150 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 6.1 “Old Dan Tucker,” attributed to Dan Emmett (New York:

Atwill, 1843). A and B indicate repetitions of melodic-rhythmic motives.

&

b

b

4

2

j

œ

I

.

J

œ

R

œ

.

J

œ

R

œ

come to town de

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

j

œ

ud-der night, I

.

J

œ

R

œ

.

J

œ

R

œ

hear de noise den

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

J

œ

saw de fight, De

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

watch-man was a

&

b

b

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

r

œ

r

œ

run - nin' roun', Cry-in'

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

Old Dan Tuc- ker's

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

J

œ

come to town, So

R

œ

J

œ

R

œ

œ

get out de way!

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

b

b

R

œ

J

œ

R

œ

œ

Get out de way!

œœ

œ

œ

R

œ

J

œ

R

œ

œ

Get out de way!

J

œ

J

œ

j

œ

J

œ

Old Dan Tuc-ker,

J

œ

J

œ

.

J

œ

R

œ

You're too late to

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

J

œ

come to sup-per.

A

A

B

A1

B

A

BA1

B1 A

A manuscript of Emmett contains a dance entitled Genuine Negro Jig

that has the kind of two-measure cell structure that would later, in the

language of twentieth-century jazz, be unhesitatingly called a riff.

21

It

also contains minor third versus major third ambiguity, another feature

of blues and jazz (ex. 6.2).

Syncopation

This is not the usual European syncopation of this period, in which the

syncopated note is accented. The syncopated note tends to have no ac-

cent; instead the accent falls on the preceding note.

22

The difference be-

Example 6.2 Genuine Negro Jig, collected by Emmett, MSS 355 Daniel D.

Emmett Papers, c. 1840–1880, Archives/Library of the Ohio Historical

Society. Columbus, OH.

&4

2

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ œ

œn

œ

≈

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ œ

œ#

œ

œ œ

œn

œ

3

&

œ œ œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

3

œ

œ#

œ

œ œ

œn

œ

≈

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

œn

œ

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 151

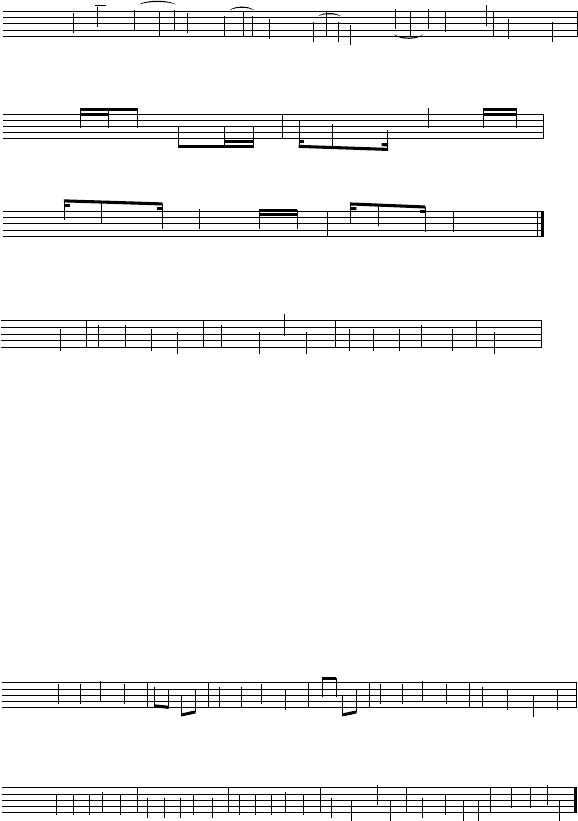

tween the two types can be heard by comparing a syncopated passage

in Suppé’s Poet and Peasant Overture with “Buffalo Gals” (ex. 6.3). Note

that the accent is on “come,” not on “out” (the syncopated note). Sim-

ilarly, toward the end of the refrain of Stephen Foster’s song “Angelina

Baker” the accent is on the note before the syncopated note.

It took awhile for this kind of unaccented syncopation to embed

itself as a popular feature. For example, there are no syncopations on

the “out” of the “get out” refrain of some versions of “Old Dan Tucker”

(ex. 6.4).

Example 6.3 (a) Dichter und Bauer (1846), Franz von Suppé; (b) refrain of

“Buffalo Gals,” as published in Davidson’s Universal Melodist (London, 1853);

(c) “Angelina Baker” (1850).

&

b

b

4

2

J

œ

œ

>

J

œ

J

œ

œ

J

œ

J

œ

œ

J

œ

J

œ

œ

j

œb

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

&

b

4

2

Allegretto

œ œ œ

œ œ œ

Buf fa lo gals, can't you

œ

œ

œ

j

œœœ

come out to night? can't you-- -

&

b

œ

œ

œ

j

œœœ

come out to night? can't you

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰

come out to night?--

(a)

(b)

(c)

Example 6.4 (a) “Old Dan Tucker,” attributed to Dan Emmit (sic) (Boston:

Keith, 1843); (b) “Old Dan Tucker,” attributed to Henry Russell (London:

Davidson, Universal Melodist, 1853).

&

#

#

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

œ

get out de way!

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

œ

get out de way!

œ œ

œ

œ

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

œ

get out de way!

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

Old Dan Tuc- ker

&

b

b

.

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

J

œ

Git out ob de way,

.

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

J

œ

Git out ob de way,

.

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

J

œ

Git out ob de way,

J

œ

J

œ

j

œ

J

œ

Ole Dan Tuc-ker;

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

You're too late to

.

j

œ

r

œ

j

œ

J

œ

come to sup-per.

(a)

(b)

&4

2

R

œ

She

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

left me here to

.

J

œ

R

œ

j

œ

J

œ

weep a tear And

R

œ

J

œ

R

œ

J

œ

J

œ

beat on de old jaw

˙

bone.-