Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Laube, later director of the Burgtheater, who heard him playing at the

Sperl gardens in Vienna in 1833: “Typically African, too, is the way he

conducts his dances; his own limbs no longer belong to him when the

desert-storm of his waltz is let loose; his fiddle-bow dances with his

arms; the tempo animates his feet.”

18

As for the revolutionary angle,

Laube remarks:

The power wielded by the black-haired musician is potentially very dan-

gerous; it is his especial good fortune that no censorship can be exercised

over waltz music and the thoughts or emotions it arouses. . . . I do not

know what other things besides music Strauss may understand, but I do

know that he is a man who could do a great deal of harm if he were to play

Rousseau’s ideas on his violin. In one single evening the Viennese would

subscribe to the entire contrat social.

19

Richard Wagner, who first visited Vienna at age nineteen, endorses

Laube’s impression, describing in Mein Leben the frenzy he witnessed at

Strauss’s playing.

20

Strauss biographer Heinrich Jacob sums up the

uniqueness of Strauss’s achievement in the phrase “till then no music

had had such demotic strength.”

21

His music was of a type that related little, however, to that which

might previously have been considered “of the people.” It was not

music to accompany work, whether milking the cow or making the

hay, nor did it function as part of traditional religious or secular rituals.

It was music forming part of an entertainment provided not to every-

one but rather to those prepared to purchase tickets. It was for the

urban social dance, not the festive village dance. Unlike rural types of

music, it was produced for urban leisure-hour consumption. That being

so, it had the advantage of being more readily available for audiences

elsewhere, since cities were beginning to share much in common in the

nineteenth century. Even a locally marked artifact could be widely de-

sirable if its origin was urban: a Parisian gown might be sought out by

fashionable society in London or New York, although rural costume

would be considered “fancy dress” outside its country of origin. The

music of the Strauss family was, likewise, recognizably of a certain

place, Vienna, but its primary purpose—at least, in the early days—was

to satisfy expectations in a particular urban space, that of the dance hall.

The music also had an urban subject position. When folk idioms were

evoked, they were being served up for an urban audience. The drone

effects and yodeling melodic phrases of Dorfschwalben aus Österreich (Vil-

lage swallows), op. 164 (1864), a waltz by Josef Strauss (1827–70), are

scarcely intended to be any more authentic than its imitation bird

calls—there is a sense of an eyebrow being raised humorously over

these devices. They are what an urban middle-class audience would

recognize as rural and not what an Upper Austrian farmer would rec-

ognize as such. Even Jacob, who believed Josef had “a realistic feeling

for nature,” admits that this waltz was “the work of a man who spent

his life in closed rooms.”

22

122 Sounds of the Metropolis

Stylistic Features

When examining Viennese waltz style, we should not neglect the im-

portance of nonnotated performance practices such as the anticipated

second beat, the use of accelerando, strongly marked ritardandi, and so

forth. They all require musical “feel,” just as do later features of popu-

lar music performance, such as “swing” and “groove.” Strauss Sr. dem-

onstrated his awareness of the importance of popular music perform-

ance conventions that are suggestive of spontaneity and intuition rather

than inflexibility and subservience to a musical score when he asked

Philippe Musard if he might play with his orchestra in order to acquire

an idiomatic understanding of French quadrille playing. Other coun-

tries, in turn, needed to acquire the feel of the Viennese waltz. The an-

ticipated second beat of the accompaniment is not something that hap-

pens relentlessly—it depends on context; but the context is judged as

much by feel as by an assessment of the melodic rhythm. Similarly, you

have to feel that a certain pushing and dragging of tempo is appropri-

ate: for example, sensing the need to pull the tempo back slightly and

to add gentle accents to each note as the melody strides downward after

having reached its high point in the third phrase of the first waltz of

Josef Strauss’s Sphären-Klänge, op. 235 (1868). When New Yorkers

finally got to hear a Viennese waltz played idiomatically (during Strauss

Jr.’s tour), they were struck by the “life and color” in the performance:

“It is really wonderful how a pianissimo or a forte, a retardando [sic] or a

crescendo, an emphatic accent or other mark of expression animates, im-

proves and heightens the effect.”

23

A crucial feature of the Viennese waltz style was its treatment of

rhythm (as Berlioz recognized when he heard Strauss Sr. in Paris).

Rhythm is more important to the music’s functional purpose than is

melody. Rhythm makes the dance, as well as signifying the dance type.

Memorable rhythmic motives frequently take precedence over melodic

development, nowhere more so than in the first waltz of Carnivals-

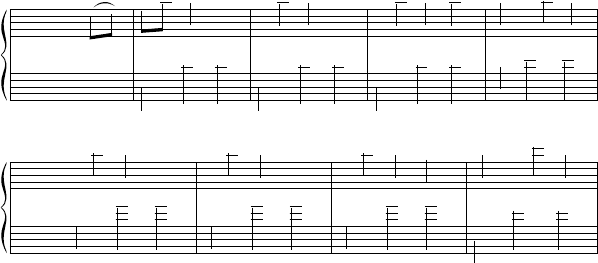

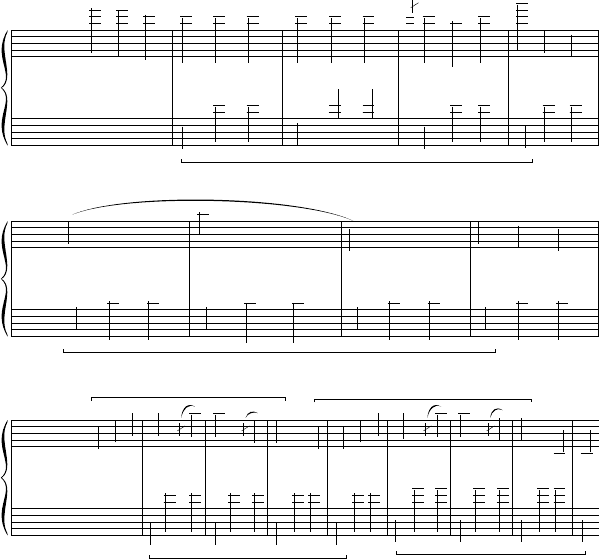

Spende, which is something between a yodel and a donkey’s bray (ex. 5.5).

A Revolution on the Dance Floor, a Revolution in Musical Style 123

Example 5.5 Strauss Sr., Carnivals-Spende, op. 60 (1833), waltz 1a.

&

?

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

p

œ

Œ

œ

.

œ

.

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

.

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

>

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

?

#

#

#

#

‰

J

œ

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

>

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Strauss Sr. also enjoys the kind of cross-rhythms that suggest two

different meters are being played at the same time (ex. 5.6).

Even when longer melodic phrases appear, they tend to be charac-

terized by unexpected rhythmic turns, accents (often emphasized by an

acciaccatura), and syncopation. In the first waltz theme of Strauss Sr.’s

Erinnerung an Berlin, op. 78 (1835), the imitations that punctuate phrases

imitate the rhythm but not the pitches of notes. This prioritizing of the

rhythmic level over the pitch level is rarely found in nineteenth-cen-

tury “classical” music (with the exception of the dance-loving Austrian

composer Anton Bruckner).

Strauss Sr. was fond of syncopation, especially in his polkas and gal-

ops, but the syncopated note is usually accented, unlike the novel kind

of syncopation introduced in blackface minstrelsy (discussed in chapter

6). The syncopation in the Trio of the Sperl Polka, op. 133 (1842), for

example (see ex. 5.7a), can be found already in Beethoven’s Piano So-

nata op. 31, no. 1, a sonata that also contains examples of “pushed”

syncopation.

124 Sounds of the Metropolis

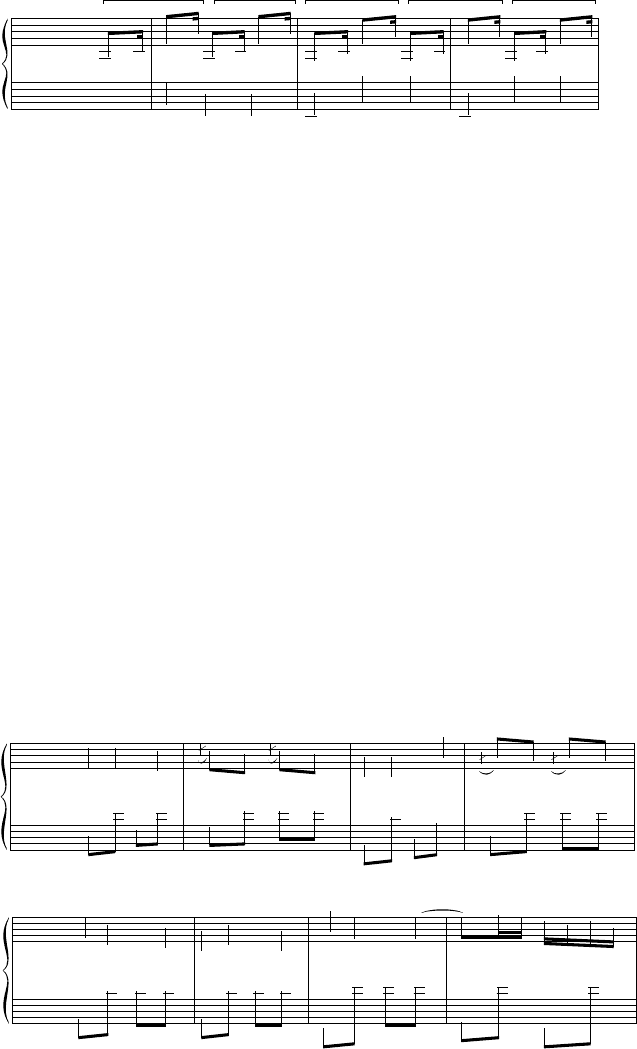

Example 5.6 Strauss Sr., Krapfen-Waldel-Walzer, op. 12 (1828), waltz 6b.

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

.

œ

p

œ

Œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Example 5.7 (a) Strauss Sr., Sperl Polka, op. 133 (1842), Trio; (b) Beethoven,

Piano Sonata No. 16 in G, op. 31, no. 1 (1802), first movement, bars 66–69.

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

4

2

4

2

J

œ

p

œ

>

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œn

œ

.

œ

.

j

œ

œ

.

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œb œ

>

j

œb

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ#

œ

.

œ

.

j

œ

œ

.

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

?

#

#

4

2

4

2

j

œ

.

p

œ#

J

œ#

œ

œ

œ

œ

# œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

.

œ#

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

# œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ#

.

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ#

œ#

œ

œ#

œ

œ

œ

œ

(a)

(b)

The use of syncopation in Strauss Sr. acts as a foil to the predictabil-

ity of the dance rhythm. The fourth waltz of Carnevals-Spende (Carnival

donation), op. 60 (1833), contains timpani strokes that anticipate each

new phrase by one beat (ex. 5.8).

24

Max Schönherr has analyzed the different rhythmic waltz types,

and arrived at sixteen rhythmic models.

25

Linke thinks he has missed

some, and adds an interesting analysis of polyrhythmic patterns.

26

Schönherr relates the syncopated variety of waltz to the Bohemian Fu-

riant (with its hemiola pattern). The hemiola rhythm is a characteristic

of Lanner, and appears in the first waltz theme of one of his best-known

waltzes, Die Schönbrunner, op. 200 (1842). Strauss Jr. makes use of this

particular syncopated rhythm in the third waltz of An der schönen blauen

Donau (On the beautiful blue Danube), op. 314 (1867).

Since the Blue Danube is so well known, I am going to use it to illus-

trate features of Viennese popular dance style. There is no great change

in style between the music of Strauss father and son: Norbert Linke

shows how Strauss Jr.’s style remained indebted to his father’s.

27

Short

motivic ideas continue to provide the material on which many waltzes

are built, and antecedent–consequent structure is usually forgone in

preference to call-and-response or dialogue between instruments (as in

waltz 1a).

28

The orchestra Strauss Jr. employs in the Blue Danube is

larger than that his father was accustomed to use, and the son uses his

orchestral imagination (evident from the beginning of his career) to

much effect in the introduction and coda. Nevertheless, many of the

devices of orchestration that follow were already typical of his father’s

dance music: staccato and pizzicato (staccato violin and pizzicato cello

in waltz 1b); short figures being highlighted with another instrument

(the piccolo in waltz 2); shifting colors, as doubling instruments are

changed during phrases of violin melody (the woodwind and brass in

waltz 3a); cellos doubling the melody one or two octaves below (waltzes

1a, 2, and 4) or moving in parallel tenths below the melody (waltz 3a);

trumpets being made to stand out by giving them a distinctive rhythm

(waltz 4a); emphasizing the dance rhythm with percussion (the snare

drum in waltz 3b); and saving additional percussion to bring excite-

ment to a climactic section (waltz 5b). The use of a trumpet to double

the melody (waltz 2b) is a feature of popular orchestration, creating an

effect that would have been thought vulgar in ernste Musik. A change of

A Revolution on the Dance Floor, a Revolution in Musical Style 125

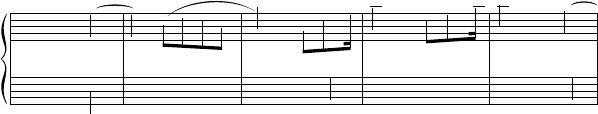

Example 5.8 Strauss Sr., Carnevals-Spende, op. 60 (1833), waltz 4a.

&

?

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

œ

>

Timp.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

∑

œ

‰

œ

.

œ

œ

Ó

œ

>

œ

‰

œ

.

œ

œ

∑

œ

Œ

œ

Ó

œ

>

texture, linked to contrasted dynamics, may be used for a responding

phrase, as in waltz 1b (an example from Strauss Sr.’s output is the Be-

liebte Annen-Polka, op. 137, 1842). It is as if a hesitant, questioning “do

you think we might . . .” receives a confident, affirmative “of course

we can!”

A frequent melodic feature is the upward-leaping interval, often

in Scotch snap rhythm or, as in waltz 1a of the Blue Danube, with the

lower note written as an acciaccatura. The effect seems typically Vien-

nese and may derive from the idiomatic violin technique of crossing

strings with the bow, or it may be indebted to the yodels of the Tyrol.

Another characteristic Viennese melodic device, this time surely of

urban rather than rural provenance, is the use of chromatic appoggiat-

uras (waltz 4a). Three other melodic techniques are to hold a note at

the end of a phrase while other melodic figures occur in the accompa-

niment (the cellos in 1a), to introduce melodic decoration by other in-

struments at a phrase ending so as to link to the next phrase (the cel-

los in 5a), and to write a countermelody (the flute in the closing section

of the coda). Strauss Jr. did not invent these techniques; the last three

can be heard in his father’s Fest-Lieder waltz, op. 193 (1846). Moreover,

that waltz shows that his father was extending some sections of the

waltz beyond sixteen measures (though not to the thirty-two-measure

sections found in the Blue Danube).

Waltz melodies are frequently characterized by grace notes, and

the Blue Danube holds plenty of examples. Strauss Sr., in his early days,

must have made an impact with the number of acciaccaturas he some-

times used (for instance, in the penultimate waltz of the Täuberln-

Walzer or the first waltz of Wiener-Carneval-Walzer, op. 3, 1827). These

grace notes had previously been most associated with the “Turkish

style,” rather than the typical “classical” style (though acciaccaturas de-

veloped as a way of giving an accent to certain notes in music for non-

velocity-sensitive keyboard instruments of the seventeenth century).

The arpeggio-based theme of the Blue Danube has an ancestor in Strauss

Sr.’s Loreley-Rhein-Klänge, op. 154 (1843). Strauss Jr. had learnt about

the dramatic use of chords from his father, and imitated the loud di-

minished seventh that begins the second half of the first waltz in Lore-

ley-Rhein-Klänge in his Sinngedichte, op. 1 (1844). In the Blue Danube,

abrupt changes of key have a similar effect: the second half of waltz 2,

for instance, plunges suddenly into B-flat major, the first melody note

D acting as a pivot point between the new key and the tonic D major.

What is most striking and revolutionary about the harmonic style

is the use of free-floating major sixths and major sevenths. The Blue

Danube has an example of the tonic with added sixth in the fourth phrase

of waltz 1a (see ex. 5.9a). On a technicality, it may be argued that the

sixth is resolved via octave transposition in the cello part, but the ear nei-

ther demands nor needs this reassurance of musical “correct grammar.”

A major sixth is added to the minor triad in waltz 2b of Wein, Weib und

126 Sounds of the Metropolis

Gesang, op. 333 (1869). These dissonances—treated as if consonances—

may be caused by parallel thirds or parallel sixths (see ex. 5.9b, c).

In the Kaiser-Walzer (Emperor waltz), op. 437 (1889), in addition to

dissonant sixths and sevenths (waltz 1a), Strauss begins to use seconds

and ninths: see the close of waltz 1a and measure 5 of waltz 3a. Josef

had already pointed the way in the first waltz theme of Dynamiden (Ge-

heime Anziehungskräfte), op. 173 (1865).

Peter Van der Merwe notes “the relation between melody and har-

mony had received a new twist” in the nineteenth century that per-

plexed theorists who were used to explaining the relationship of melody

notes to accompanying chords.

29

The new popular style had begun to

use notes that could not be explained with reference to the “rules” of

classical harmony. Moreover, Van de Merwe points out that melody and

harmony “seldom go in harness” as they do in the classical style: a se-

quential melody (like the opening waltz of Künstlerleben, op. 316, 1867)

does not necessitate sequential harmonies, and vice versa.

30

Waltz 3b

of Strauss Sr.’s Sperls Fest-Walzer, op. 30 (1829), is a very early example

of his treatment of the sixth as an addition to the tonic chord in a way

that scarcely demands resolution. (The melodic sequence suggests it is

A Revolution on the Dance Floor, a Revolution in Musical Style 127

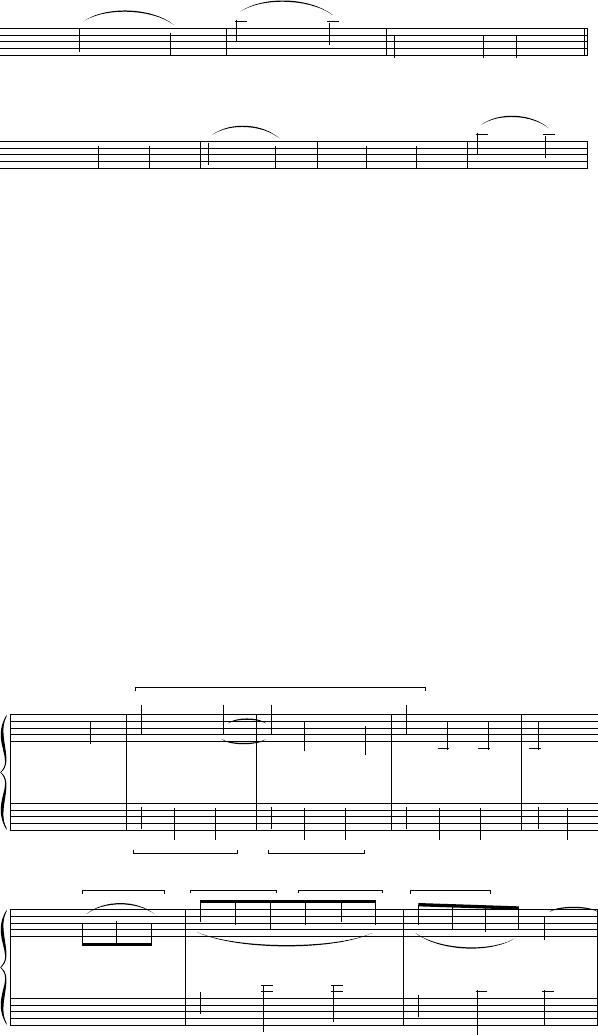

Example 5.9 (a) Strauss Jr., An der schönen blauen Donau, op. 314 (1867),

waltz 1a; (b) Strauss Jr., Künstlerleben, op. 316 (1867), waltz 4b; (c) Strauss

Jr., Geschichten aus dem Wienerwald, op. 325 (1868), waltz 1a.

&

?

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œŒ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

?

4

3

4

3

œ

œ

p

.

.

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

˙

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

˙

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

?

b

b

4

3

4

3

J

œ

œ

#

n

p

‰

˙

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

#

n

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

#

n

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

Œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

(b)

(a)

(c)

as much part of the tonic harmony as the leading note is part of the

dominant in the first measure; see ex. 5.10.)

The added sixth permeates many of his waltzes, and it is part of the

new Viennese sound that Linke sees as largely Strauss’s achievement.

31

The free-floating sixth passed into popular music elsewhere and, as we

shall see in chapter 7, was one of the things about London music hall

songs that irritated high cultural critics like Hubert Parry. Another fea-

ture of the new Viennese sound is the wienerische Note, the leading note

that falls rather than rises, producing a yearning effect over subdomi-

nant or supertonic harmony. It can be heard strikingly, approached un-

compromisingly by a leap of a major seventh, in Strauss Sr.’s waltz

Heimath-Klänge (Homeland sounds), op. 84 (1836) (see ex. 5.11).

Strauss Sr. moved toward more cohesiveness in his waltz structures

as the 1830s wore on, using inner connections in his Erinnerung an

Berlin of 1835. At the same time that he sought greater unity, he showed

a concern with variety of phrasing—upbeat phrases, on-the-beat phrases,

and phrases of different lengths, though usually obeying a regular hy-

permetric scheme of four-measure units.

32

In waltz 4 of Erinnerung an-

Berlin, by delaying the entry of the bass and accompanying chords,

Strauss Sr. deceives the listener into hearing the first measure as a

three-beat anacrusis, thus creating an ambiguity between the phrasing

structure and the regular measure groupings within the eight-measure

sections (the hypermeter). This would not be possible in the old figure

dances, but the waltz is not a figure dance—in a certain sense, as Mark

Twain put it: “You have only to spin around with frightful velocity and

steer clear of the furniture.”

33

The first waltz of the Blue Danube, the tune of which also forms the

basis of the romantic introduction, has an anacrusis of a whole mea-

128 Sounds of the Metropolis

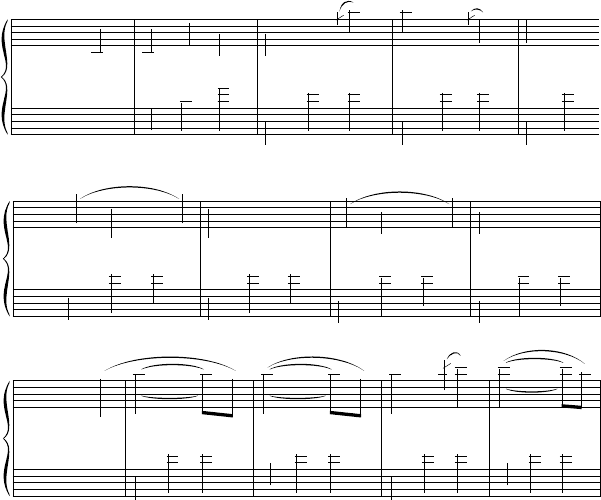

Example 5.10 Strauss Sr., Sperls Fest-Walzer, op. 30 (1829), waltz 3b.

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

p

œ

Œ

˙

œ#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

œ

œn

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Example 5.11 Strauss Sr., Heimath-Klänge, op. 84 (1836), waltz 1b.

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

j

œ#

.

.

˙

˙

>

f

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

.

.

˙

˙

>

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

˙

˙

>

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

œ#

#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

˙

˙

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

sure’s duration, extended further by an additional beat in succeeding

phrases. There is almost a sense of bass and melody being one measure

adrift, just as there is in waltz 2a of his father’s Loreley-Rhein-Klänge (see

ex. 5.12).

A five-measure melodic phrase synchronizes the parts (his father

used a three-measure phrase to do likewise). Waltz 1b has a two-beat

anacrusis, and begins without preparation in the dominant key. It

shares melodic connections with 1a (see ex. 5.13).

Waltz 2a returns to the tonic, but begins with dominant seventh

harmony. Against idiomatic string accompaniment, the new melody

reveals rhythmic connections with the woodwind interjections in 1a,

and varies a legato idea from the penultimate phrase of 1a. Waltz 2b is

contrasted in key and dynamics and introduces a syncopated idea that

anticipates the next waltz. Waltz 3 begins with a melody that intro-

duces the cross-rhythm 3/2 against 3/4, while the second half intro-

duces a cross-rhythm of 3/8 against 3/4 (see ex. 5.14).

Waltz 4, introduced by four measures of modulation, illustrates the

necessity for knowledge about performance practice that is not to be

A Revolution on the Dance Floor, a Revolution in Musical Style 129

Example 5.12 (a) Strauss Sr., Loreley-Rhein-Klänge, op. 154 (1843), waltz 2a;

(b) Strauss Jr., An der schönen blauen Donau, op. 314 (1867), waltz 1a.

&

?

b

b

b

b

4

3

4

3

œ

œ

.

p

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

.

∑

J

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

˙b

j

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œn

n

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

.

œn

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

?

b

b

b

b

.

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

#

n

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

.

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

?

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

œ

œ

∑

œ

Œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

(a)

(b)

found written in the score. It begins with a tune that demands rubato

performance and proceeds to a second half that needs to be più mosso

but in strict tempo. Once more, thematic relationships are evident: the

rhythm of the first measure of 4a is that of the second measure of 3b,

and the rhythm of the sixth measure of 4b is akin to that of the third

measure of waltz 3b. There is an interesting harmonic sleight of hand

between the two halves of waltz 4. The end of the first half implies a

return to the tonic key, but it is thwarted by a sforzando chord. How-

ever, this is an example of Strauss’s long-term planning, since this pas-

sage will be used to return the music to the tonic following the reap-

pearance of waltz 4a in the coda.

A modulating section of ten measures establishes the dominant

key, and the final waltz begins with an anacrusis of a whole measure’s

duration, as did the first waltz. Its second half has no upbeat, and its

130 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 5.13 Strauss Jr., An der schönen blauen Donau, op. 314 (1867),

waltz 1 (measures 30–32, 37–40).

&

#

#

4

3

˙

>

(End of waltz 1a)

œ

˙

>

œ

œ

‰

J

œ œ

&

#

#

Œ

J

œ

(Bars 4–7 of waltz 1b)

‰

J

œ

‰

˙

>

œ

Œ

J

œ

‰

J

œ

‰

˙

>

œ

Example 5.14 (a) Strauss Jr., An der schönen blauen Donau, op. 314 (1867),

waltz 3a; (b) waltz 3b.

&

?

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

p

Œ

œ

œ

Œ œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

>

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

m

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

œ

œ

œ

&

?

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

p

œ

œ

‰Œ

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

(a)

(b)

tune is related to the first half as well as to waltz 4b. It conveys clearly

a sense of being a climactic section, with a feeling of exhilaration that

is enhanced by the rhythmic figures on the bass instruments during the

melody’s sustained notes at phrase endings. The long coda then begins

with its reminiscences of waltz themes 3a, 2a, 4a and, finally, 1a. After

a general pause, there is a return to the romantic atmosphere of the in-

troduction, but with echoing phrases on solo flute that convey a vale-

dictory sentiment as the waltz concludes.

Music and Business

The categorization of a type of urban music as Unterhaltungsmusik was

inextricably linked to the industrial production of sheet music and the

growth of the music entertainment business. An international market

for popular music had opened up in the West in which the popular

managed to bear a local character at the same time as it transcended the

local. At the end of his life, Strauss Sr. had succeeded in becoming the

world’s most popular musician.

Strauss is the most popular musician on earth. His waltzes enrapture the

Americans, they resound over the Wall of China, they triumph in the Af-

rican bivouac, and a Viennese woman friend of mine wrote recently

about how deeply it moved her, when she entered onto Australian soil

and a beggar with a Strauss waltz asked for alms. In Europe, he spread

personally the thrice-sweet teachings of the divine carelessness of the old

Vienna.

34

His early steps had been taken in partnership with Joseph Lanner,

a glove maker’s son born at Oberdöbling near Vienna in 1801. Lanner,

an ex-member of Michael Pamer’s dance band, had formed a trio con-

sisting of two violins and guitar, and before long asked Johann Strauss—

also of petit bourgeois origin—to join him.

35

The band next became a

string orchestra, but Lanner and Strauss went their separate ways in

1825.

36

Rivalry began between the two, especially after the success of

Strauss’s Kettenbrücke-Walzer, op. 4 (1827), and each musician had pas-

sionate admirers—Strauss’s music was found fiery, Lanner’s sweeter,

more sentimental.

37

Lanner was honored with the aristocratic engage-

ment at the Redoutensäle; Strauss was hired at the bourgeois Sperl

dance hall. It might have been thought that Lanner had achieved higher

status, but Strauss was more aware of the new commercial age and its

possibilities. He had been one of the first to realize that it was finan-

cially more advantageous to issue tickets for performances in parks and

gardens than to take postperformance collections. He built up his own

orchestra into a highly disciplined unit, gaining experience performing

in inns and dance halls (several of which establishments appear in the

titles of his early dances). He then set his sights on making money and

fame by touring, something Lanner was not disposed to undertake.

A Revolution on the Dance Floor, a Revolution in Musical Style 131