Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

beautiful and pleasant and gay in Vienna.”

129

This parallels the admira-

tion that still existed in London for the music of Arthur Sullivan at the

time he died, a year after Strauss Jr. The Times obituary for Sullivan ac-

knowledged this high regard, found everywhere except, it noted wryly,

among those “musicians of earnest and highly cultivated taste.”

130

Notwithstanding the appeal of folk music to those who were “un-

critical,” efforts to cultivate taste were undiminished. Henry Wood, dis-

cussing the initial planning of promenade concerts at Queen’s Hall,

London, in 1895, quotes the musical entrepreneur Robert Newmand

(the Hall’s lessee): “I am going to run nightly concerts and train the

public by easy stages . . . [p]opular at first, gradually raising the stan-

dard until I have created a public for classical and modern music.”

131

Here

we have the term “popular” being used clearly in the sense of inferior

(music of a lower standard) and also as something to be contrasted with

“classical” music. At the first prom, songs alternated with orchestral

and instrumental items (which included a cornet solo). “This was,”

Wood explains, “a new venture, and as such it had to be popular.”

132

“Serious music” in the later nineteenth century became more and

more confused with autobiography—the belief that it was a portrayal

of “inner feelings.” Composers were presumed to be offering some-

thing of themselves, something personal, and certainly not something

concerning the self of the listener, beyond the recognition of a common

humanity. A paradoxical antidote to the idea of art as autobiography is

Josef Strauss’s waltz Mein Lebenslauf ist Lieb’ und Lust! op. 263, which,

far from conveying the conviction that the composer’s life is all love

and pleasure, is a composition designed to convince listeners or dancers

that their lives are like that. As an emotional summation of Josef Strauss’s

own curriculum vitae (Lebenslauf), a brief journey filled with constant

work and cigar smoke, it rings so hollow that it can as readily prompt

sadness as joy.

Bourgeois female accomplishments and working-class rational rec-

reations now seemed insufficiently dedicated to the shrine of art. A cor-

respondent complained to the editor of the Musical Times in 1880 about

an article on notation in Grove’s Dictionary of Music, that said that Tonic

Sol-fa “could never be used for any other purpose than that of very

commonplace singing.”

133

As if that were not insult enough, the preface

by Lucy Broadwood and J. A. Fuller Maitland to English Country Songs

(1893) reveals antagonism from another quarter, that of the new breed

of folk song collectors, toward Tonic Sol-fa choirs and their “fatuous

part-songs.” Even the oratorio had now declined in status, although in

1861 it had received unstinting praise: “The oratorio is the highest form

of musical composition, combining in itself the two great divisions,

vocal and instrumental, in their most complete development.”

134

In the

summer of 1880, the New York Times ran three editorials opposed to the

enthusiasm for brass instruments and brass bands. At this time, Sousa

increased the number of reeds in his band, bringing it closer to the clas-

112 Sounds of the Metropolis

sical orchestra and making it more acceptable to the music critics,

though not all approved of the way he mixed the “classics” and the

“popular.”

135

In the first half of the century, popular music was possible

in the “best of homes,” but from now on the message of “high art” was

that there was a “better class of music” and another kind that appealed

to “the masses.” This laid the ground for mass culture critique, which

proceeds from the following group of negative premises: there is a type

of culture solely about profit; it debases high culture by borrowing from

it; it harms people by offering spurious gratification and making them

passive consumers; and it reduces a society’s total cultural quality.

136

The friction between entertainment and art continued well into the

twentieth century. A law passed in Austria in 1936, and not challenged

until the 1970s, enabled 2 percent of royalties derived from “entertain-

ment” music (Unterhaltungsmusik) to be reallocated to those making

“serious” music.

137

The Rift between Art and Entertainment 113

This page intentionally left blank

II

STUDIES OF

REVOLUTIONARY

POPULAR GENRES

This page intentionally left blank

5

A Revolution on

the Dance Floor,

a Revolution in

Musical Style

The Viennese Waltz

117

This chapter investigates and evaluates evidence for the claim that the

Viennese version of the revolving dance known as the waltz stimulated

the development of a revolutionary kind of popular music that created

a schism between entertainment music (Unterhaltungsmusik) and seri-

ous music (ernste Musik). As a consequence, the idea of the “popular”

changed, and although the concept of a music liked by many people did

not disappear, popular or light music soon began to be associated with

business and commercial success. That is why calling pieces like Mo-

zart’s divertimenti “popular” leads to confusion. I gave some consider-

ation in the previous chapter to Carl Dahlhaus’s view (though it was a

view I contested) that a distinction should be drawn between the de-

sire for wide appeal that arises from eighteenth-century philanthropy

and one that he regarded as springing from the manipulations of nine-

teenth-century capitalism. Adopting William Weber’s term, we might

say a “general taste” prevailed in eighteenth-century concert life; yet

that taste consensus was dissipated as nineteenth-century capitalism

brought an increasingly commodified structure to bear on musical pro-

duction. The consequence was that some music came to be promoted

as serious—demanding learning and attentive listening—and another

kind was promoted as entertainment.

Most accounts of the popularity of the dance music of nineteenth-

century Vienna have tended to concentrate on the social history of the

period and autobiographical information about the Strauss family.

1

Yet

the origins of the Viennese waltz, its revolving movement and its inno-

vative musical style, are still matters of uncertainty. It has been com-

mon, for instance, to emphasize the importance of the Ländler to the

waltz and neglect the influence of the Dreher. The whirling type of dance

had been popular in the German countryside since at least the mid–six-

teenth century, and various authorities attempted to prohibit dances

with unseemly turns (unziemblichen Verdrehen).

2

The Dreher, in particu-

lar, was opposed by ministers of religion, and it was this dance that led

most directly to the waltz.

3

Turning or rotating dances (drehen means to

turn, walzen to rotate) were regarded as morally reprehensible in high

society because they were likely to cause a woman’s skirt to fly up.

However, they were not banned in Vienna, where the aristocracy liked

to believe they had not lost touch with ordinary people, an attitude

they were able to sustain because Vienna at the end of the eighteenth

century did not suffer the poverty found in London or Paris. There was

already a mania for dancing at that time, and it was satisfied by a large

number of suburban dance halls. One energetic dance was the Langaus,

which had a slide instead of the Ländler’s hop and could thus be danced

at faster speed. The waltz, which also had a gliding movement, devel-

oped in bars and taverns along the Danube. The river was much used

for transport, and musicians from the country sailed downriver playing

to passengers and in establishments close to where the boats were

moored. Strauss Sr.’s father was an innkeeper on an island in the Dan-

ube in the suburb of Leopoldstadt.

4

J. H. Kattfuss’s Taschenbuch für Freunde und Freundinnen des Tanzes

(Leipzig, 1800) says that the only difference between the steps of the

Dreher, Ländler, and waltz is that the pace of the Ländler is slower. Yet

the waltz had already developed other differences. In the Ländler, the

woman revolved beneath the man’s raised arm while he stamped a

foot, and each of them revolved in opposite directions and around each

other back-to-back, as well as performing other figures that do not ap-

pear in the waltz. Moreover, the feet are dragged in the waltz, giving a

gliding motion to the whirling that marks it out as an indoor dance;

hopping movements in the Ländler were suited to rough terrain, and

country shoes with nails lent emphasis to the stamping. A gliding mo-

tion could be faster on wooden floors, and outdoor boots were frowned

on in dance halls.

5

The first parquet floor was laid at the Monschein

Hall in 1806, although in 1797 the Journal des Luxus und der Moden was

already claiming that the Viennese waltz was the fastest.

6

Naturally, the

faster the waltz, the tighter the grip that was needed on the bodies of

each partner; it meant that, allowing for due decorum, waltzes tended

to be played more slowly for the aristocracy. The tempo of the waltz al-

tered to suit fashions in women’s dresses. It slowed down for the nar-

rower styles of the early nineteenth century, but when fuller skirts

began to develop in the 1820s it speeded up again.

The waltz entered France (via Alsace) in the late eighteenth cen-

tury, and came to England at the same time, but possessed many Ländler-

118 Sounds of the Metropolis

like features. In Thomas Wilson’s manual on waltzing issued in 1816, we

are still far from the Viennese type of similar date.

7

Moral worries con-

tinued (see chapter 3), now being concerned with eroticism, the face-

to-face position, and the contact between bodies unshielded by heavy

corsetry. The biggest initial boost to the Viennese waltz was the holding

of the Peace Congress in Vienna, 1814–15. Diplomats at the Congress

of Vienna (at the Hofburg) visited the palace ballrooms so frequently

that the well-known quip arose, “le Congrès ne marche pas, il danse.”

Unterhaltungsmusik and Popular Style

A crucial development occurred in the 1820s, in the dance music of Jo-

seph Lanner (1801–43) and Strauss Sr. (1804–49). As a writer looking

back on this period in the Musical Times of May 1895 declared, “Haydn

and Mozart . . . left the courtly dance of the last century pretty much

where they found it, but the Strauss waltz is almost a distinct cre-

ation.”

8

Lanner and Strauss, and especially the latter, saw the possibil-

ity of a popular revolution in music, and created a style that was often

consciously at odds with the art music of its time. It was a style that gave

new meaning to entertainment music: the thesis here being that the

concept of the “popular” began to embrace, for the first time, not only

the music’s reception but also the presence of specific features of style.

9

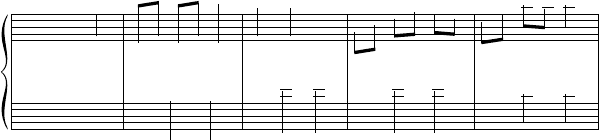

It is the accent on beat 1 that is crucial to the waltz, though there

is often has an accent on beat 3 also. The Ländler has a characteristic ac-

cent on beat 2, as can be found in Franz Schubert’s 8 Ländler, D378, for

piano (1816). It is especially noticeable in the seventh of these dances,

since Schubert marks the accent (see ex. 5.1).

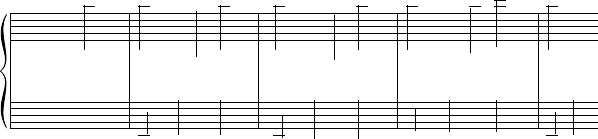

Schubert introduced unexpected modulations into his later piano

waltzes of the 1820s, and began to make more use of “um-pah-pah”

figures (the term is “Hum-Ta-Ta” in Vienna). The waltz he published in

Moderne Liebeswalzer in 1826 (D979) reveals stylistically his familiarity

with Lanner’s music (see ex. 5.2).

10

The accent on beat 1 in the waltz came about as it gained speed; it

is not such a noticeable feature of early waltzes. The “um-pah-pah” ac-

companiment is rare, or scantily applied, before Lanner and Strauss.

11

Another distinction between the waltz and Ländler is that the violin

had not traditionally accompanied the Ländler, yet Strauss and Lanner

A Revolution on the Dance Floor, a Revolution in Musical Style 119

Example 5.1 Schubert, no. 7 of 8 Ländler, D378 (1816).

&

?

b

b

b

b

4

3

4

3

œ

F

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

Z

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

made the most of their skills as violinists and composed idiomatically

for this instrument. Waltzes had commonly been published in groups

of six, each waltz being in a binary form consisting of two repeated

eight-measure sections. Strauss established a new waltz structure of an

introduction, a sequence of five waltzes (each binary), and a coda re-

prising the best tunes. He first used this form in Gute Meinung für die Tan-

zlust (Good opinion for dance pleasure), op. 34, composed for the Car-

nival of September 1830. Before this, he generally preferred six waltzes

and a coda with little or no introduction. The new form was, however,

already there in embryo in his Heitzinger-Reunion-Walzer, op. 24 (1829).

12

Carl Maria von Weber’s widely played “rondo brilliant” for piano, Auf-

forderung zum Tanz (Invitation to the dance) of 1819, was undoubtedly

an influence, since its unique feature was that it framed a set of waltzes

with an introduction building expectation, and a reflective epilogue.

Strauss did more than set in place a structural convention; he also es-

tablished a distinctive Viennese character and sound, partly drawn from

traditional airs and partly invented.

13

Gute Meinung für die Tanzlust is

again a crucial work in this regard, with its yodeling figures (waltz 1a

and 2b), sighing appoggiaturas (1b, and the wienerische Note in 5a), and

the ease with which it moves from modern syncopations (2a) and chro-

maticism (3b) to old Ländler patterns (4a and 5b). The new dance music

of the 1830s consolidated the Viennese identification of themselves

with this style. Composer Richard Heuberger, who experienced the

music of this period as it first entered the ballroom, claimed that people

recognized their own traits in it.

14

Strauss began to extend the eight-measure sections of the waltz to

sixteen measures, sometimes by having a varied repeat, so that instead

of theme A (eight measures) ⫻ 2, we have A ⫹ A1 (making sixteen

measures) ⫻ 2. Another technique was to return to the A section after

the B section. Allowing ideas to reappear also gives coherence to the

waltz sections. His willingness to introduce irregularities is evident

even in his early Täuberln-Walzer, op. 1 (1827). The third waltz theme

has a second half that is twelve measures long, and the final waltz

theme, 7b (8b in the piano version) is also twelve measures.

15

All its

other themes are eight measures, but some repeats are varied.

16

Waltz

theme 6b (7b in the piano version) shows that Strauss’s inventiveness

regarding syncopation is with him from the beginning (see ex. 5.3).

120 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 5.2 Schubert waltz from Moderne Liebeswalzer (1826).

&

?

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

œ

p

Œ

.

.

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

The short syncopated note as notated here might suggest an anticipa-

tion of the second beat of the measure that was to become one of the

most recognizable features of Viennese waltz style, the Viennese lilt

(the slight anticipation of the first “pah” of the “oom-pah-pah”).

The Täuberln-Walzer is scored for a small orchestra consisting of

flute, two clarinets, two horns (doubling trumpets), trumpet, three vi-

olins, double bass, and timpani (E and B, tonic and dominant). There

has been speculation that Lanner had commandeered the viola and

cello players for his own orchestra after his split with Strauss, but it may

well be that Strauss liked this combination (in fact, when he began to

increase the size of his orchestra, he added wind rather than strings).

The sound of a double bass (often a smaller model than the norm)

rather than cello has a history in Viennese dance music, and elsewhere

in Austria, as some of Mozart’s early divertimenti show.

17

Lanner com-

posed his Dornbacher Ländler, op. 9 (c. 1824), for three violins and

double bass. Early Viennese dance music often had two violins and a

double bass, plus a guitar or clarinet and percussion.

The “pushed” note—the note played slightly ahead of the beat—

became a characteristic feature of twentieth-century popular music. As

just noted, it is already in evidence in the Viennese waltz, and evident

from the notation (ex. 5.4).

Elsewhere, the “pushing” is not so mechanistic as to require or, in-

deed, gain clarity from being notated. It is often a question of “feel,” as

in the “swing feel” of jazz. It cannot be performed mechanically. In an-

other pointer to the future of popular music (the importance of Afri-

can-American music making), it is interesting to find that the person

who might be thought of as the initiator of the popular music revolu-

tion (Strauss Sr.) was compared to an African by the writer Heinrich

A Revolution on the Dance Floor, a Revolution in Musical Style 121

Example 5.3 Strauss Sr., Täuberln-Walzer, op. 1 (1827), waltz 6b.

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ

p

Œ

.

œ

œ‰

J

œ

.

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

.

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ‰

J

œ

.

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

.

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Example 5.4 Strauss Sr., Carnivals-Spende, op. 60 (1833), waltz 5b.

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

4

3

4

3

œ œ

œ œ

ŒŒ

j

œ#

‰

j

œ

‰

œ

>

Ó

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

Œ

œ

œ

œ œ

∑

j

œ#

‰

j

œ

‰

œ

>

Ó

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

Œ

œ

œ

œ œ

∑