Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

thorne unmasks himself as an “aesthetic sham” in Patience (1881) also

unmasks the artificiality of dramatic soliloquies delivered in recitative.

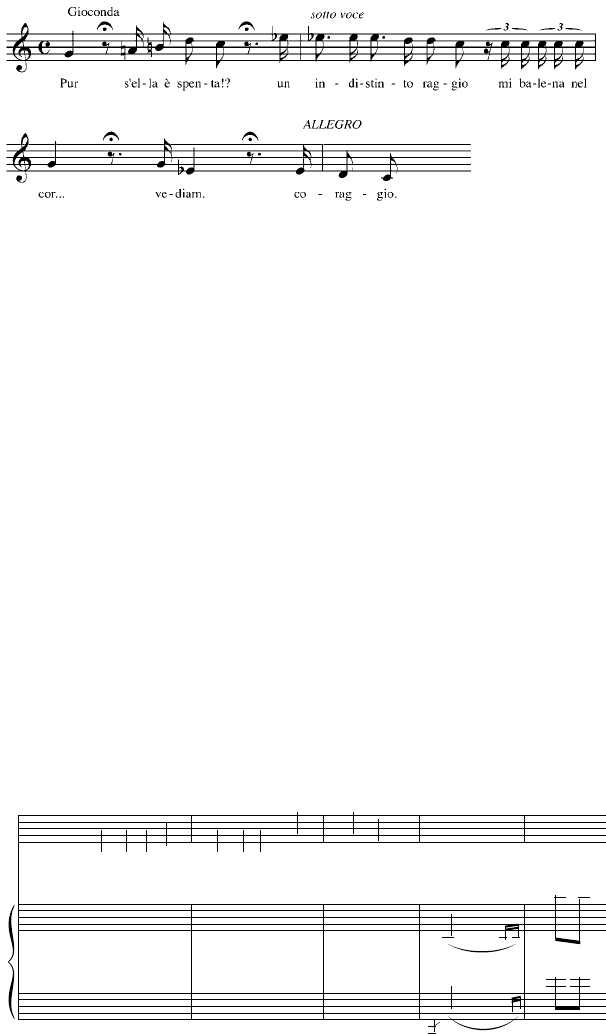

In act 4 of Amilcare Ponchielli’s La gioconda (1876), for example, the

heroine is confessing her innermost thoughts, wondering if there is a

possibility of finishing off her sleeping rival and getting her man back

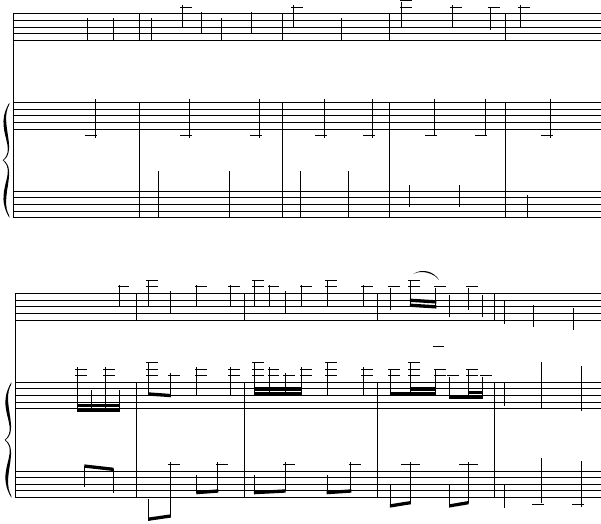

(see ex. 4.2). Compare that with Bunthorne, who is ready to confess

his own inner thoughts—provided nobody is listening (ex. 4.3).

Bunthorne’s recitative makes play with the ridiculousness of pri-

vate confessions before an audience: he confirms he is alone and unob-

served, yet we in the audience know we’re watching him. This recita-

tive also exaggerates the drama of such scenes: notice how the short

rhyming scheme provided by Gilbert and the loud orchestral stabs pro-

vided by Sullivan undermine the dramatic tension by their deliberate

triviality. (“This air severe . . . is but a mere . . . veneer!”)

Another favored moment for parody is the inquisitive or comment-

ing operatic chorus, a body of people who somehow manage to think

up identical questions simultaneously and pose them in a perfectly syn-

102 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 4.2 Recitative, “Pur, s’ella è spenta!” Amilcare Ponchielli,

La Gioconda (1876), act 4.

Example 4.3 Recitative, “Am I alone and unobserved?” Patience (1881),

act 1.

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

4

3

4

3

4

3

Ÿ~~~~~

Ÿ~~~~~

œ

Bunthorne

.

J

œ

R

œ

œb

Am I a lone,

∑

∑

‰

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

œ

And un ob served?

∑

∑

‰

j

œ

œn

Œ

I am!

∑

∑

∑

.

˙

ƒ

a tempo

œn

œ

j

œ

.

˙

œn

œ

Œ

œ

œb

b

>

œ

œn

n

>

œ

œ

œ

#

b

>

œ

œ

œ

>

---

chronized manner. In act 1 of La sonnambula, Teresa announces that the

hour has come when the phantom appears; the chorus declares, “That’s

true!” Rodolfo inquires, “What phantom?” The chorus replies, “It’s a

mystery.” Rodolfo pronounces it foolish. “What are you saying? If you

only knew!” cries the shocked chorus. Rodolfo wants to know, and this

functions as a cue for a song in which the villagers narrate the entire

history of the phantom in strict tempo. The artificiality of this kind of

interaction between solo character and chorus can be heightened if it

concerns more mundane matters, as when Captain Corcoran arrives on

board H.M.S. Pinafore (ex. 4.4).

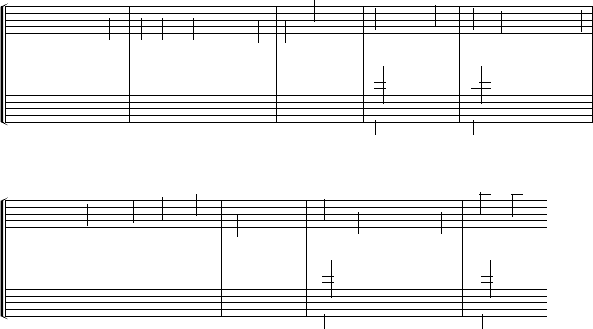

Fun can also be made of the conventional operatic use of the cho-

rus by stressing the chorus’s inability to perform furtive actions or

achieve the appropriate level of discreet silence demanded by certain

scenes. The initially hushed and circumspect Gallic warriors in act 2 of

Bellini’s Norma (1831) suddenly throw caution to the winds to declaim

loudly: “Let us prepare to accomplish our great task in silence” (ex. 4.5).

Offenbach parodied this sort of thing with his heavy-footed carabinieri

in Les Brigands (1869), as did Sullivan with his pirates (ex. 4.6).

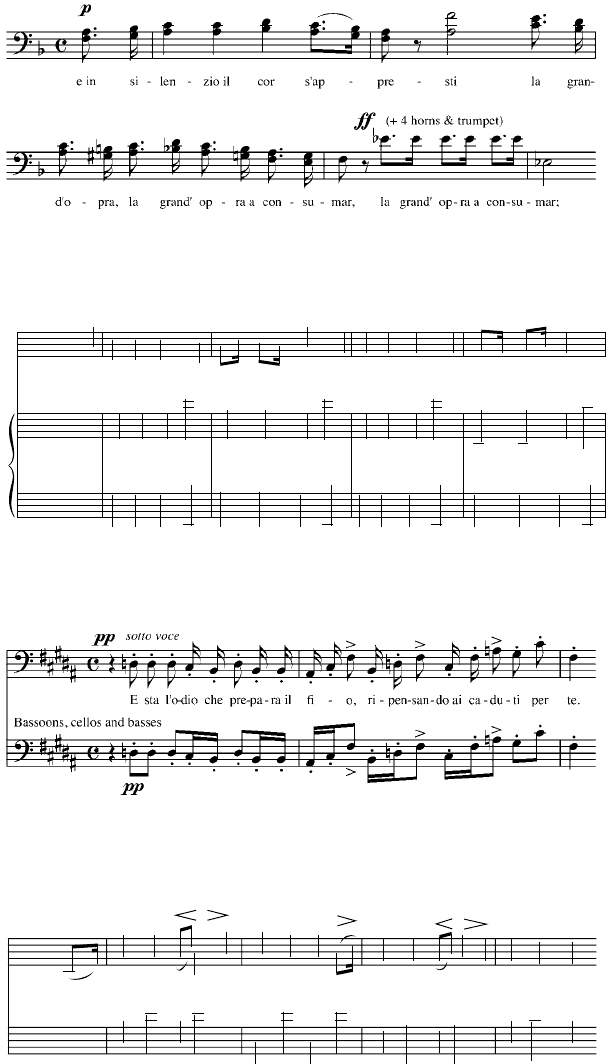

The parody of operatic choruses is certainly not exhausted by these

examples. Consider the conspiratorial group revealing dastardly plans

sotto voce in a sinister staccato, as does the gang of cutthroats in act 2,

scene 2, of Verdi’s Macbeth (1847), or the conspirators of Un ballo in

maschera (1859), and compare them with those in Charles Lecoq’s La

Fille de Madame Angot (1872; exs. 4.7, 4.8).

I turn now to stock scenes and clichés. The operatic curse is a pow-

erful weapon; witness its effect in Verdi’s Rigoletto (1851) and Simon Boc-

The Rift between Art and Entertainment 103

Example 4.4 Entrance of Captain Corcoran, H.M.S. Pinafore (1878), act 1.

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

4

2

4

2

◊◊

≈

R

œ

Captain Corcoran

My

‰

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

≈

R

œ

gal lant crew, good mor

∑

J

œ

j

œ

Œ

ning!

?

∑

œ

Chorus

‰≈

R

œ

Sir, good

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

Œ

J

œ

J

œ

‰≈

r

œ

Captain Corcoran

mor ning!

I

&

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

Œ

-

-

-

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

◊

◊

.

j

œ

r

œ

j

œ

j

œ

hope you're all quite

∑

œŒ

well.

?

∑

J

œ

Chorus

J

œ

‰≈

R

œ

Quite well, and

œ

œ

œ

Œ

œ

Œ

J

œ

J

œ

you, sir?

œ

œ

œ

œ

104 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 4.5 Chorus, “E in silenzio,” Norma (1831), act 2.

Example 4.6 Chorus, “With cat-like tread,” The Pirates of Penzance (1879),

act 2.

&

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

c

c

c

j

œ

f

With

‰

‰

œ œ

.

œ

J

œ

cat like tread, Up

j

œ

œ

p

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

ƒ

‰

J

œ

œ‰

J

œ

œ‰

J

œ

œ‰

j

œ

œ

‰

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

j

œ

on our prey we steal; In

j

œ

œ

p

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

ƒ

‰

J

œ

œ‰

J

œ

œ‰

J

œ

œ‰

j

œ

œ

‰

œ œ

.

œ

j

œ

si lence dread Our

j

œ

œ

p

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

ƒ

‰

J

œ

œ‰

J

œ

œ‰

J

œ

œ‰

j

œ

œ

‰

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

Œ

cautious way we feel!

j

œ

œ

œ

p

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

ƒ

‰

J

œ

œ‰

J

œ

œ‰

J

œ

œ‰

j

œ

œ

‰

-- - -

Example 4.7 Chorus, “E sta l’odio,” Un ballo in maschera (1859), act 1.

Example 4.8 Chorus, “Quand on conspire, quand sans frayeur” La Fille

de Madame Angot (1873), act 2.

&

?

c

c

.

œ

π

œ

Quand

Œ

j

œ

‰

j

œ

‰

œ

œ

J

œ

j

œ

on cons pi re quand

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰

j

œ

‰

j

œ

‰

.

œ

œ

sans fra yeur on

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰

j

œ

‰

œ

œ

j

œ

j

œ

peut se di re cons

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰

j

œ

‰

j

œ

‰

pi ra teur,

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

-- - - - - -

canegra (1857). Indeed, its impact is undiminished in the latter, even

though poor Paulo has been tricked into cursing himself. Thus we find,

in Patience, it is enough for Bunthorne merely to threaten to curse

Archibald Grosvenor in order to get his way. At the opposite extreme

from the venomous curse is the scene of rapture as young lovers fall

into each other’s arms. The scene of operatic ebbrezza, or rapture, is so

familiar that in La Périchole an overjoyed Périchole and Piquillo need

only remind us with an economical “joie extrême, bonheur suprême,

et cetera, et cetera.” After having restricted Nanki-Poo to an expression

of “modified rapture” in The Mikado, Gilbert and Sullivan rang a new

change on this type of scene in Yeomen of the Guard (1888) when, in the

act 2 duet “Rapture, rapture,” what Dame Carruthers interprets as joy-

ful Sergeant Meryll interprets as ghastly. Plenty of other stock scenes

are ripe for parody. In La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867), the grand

operatic ceremonial scene is mocked, as the Duchess hands over with

a ritualistic gesture that talismanic object, her father’s sword. Offen-

bach works up a portentous and throbbing Meyerbeerian accompani-

ment for soloist and chorus in the “couplets du sabre.” Family escutch-

eons and oaths also provide fodder for amusement in operetta.

Alongside satire of the high moral tone adopted by operatic heroes

and heroines, there is a joy in sending up the heroic style of their music,

especially their vocal pyrotechnics, extended melismas, and cadenzas.

Also begging to be sent up are the vocal flourishes that principal sopra-

nos so often add as decoration while a chorus sings—for example,

Amina’s “Sovra il sen la man mi posa” (La sonnambula). They reappear

skittishly in songs like “Poor wand’ring one” from Pirates. Once more,

the parody works by highlighting artifice. It often works though the ef-

fect of bathos, which is created by providing elaborate melismas for the

least likely words. When Helen realizes that Paris stands before her, the

man who, in his famous judgment, awarded the prize of an apple to

Venus, she cries out “l’homme à la pomme!” and proceeds to lavishly

embellish the phrase. Sometimes, an exaggerated flourish can poke fun

at the sentiments being expressed. An example is the melisma Sullivan

writes to underline the assertion “He remains an Englishman” in Pina-

fore (1878) (ex. 4.9), choosing to elongate the syllable “Eng-” rather

than “remains,” which would not have had such an absurd effect. In La

Belle Hélène, the concern felt for Menelaus’s honor is revealed as false

by the absurdity of the vocal flourishes (ex. 4.10).

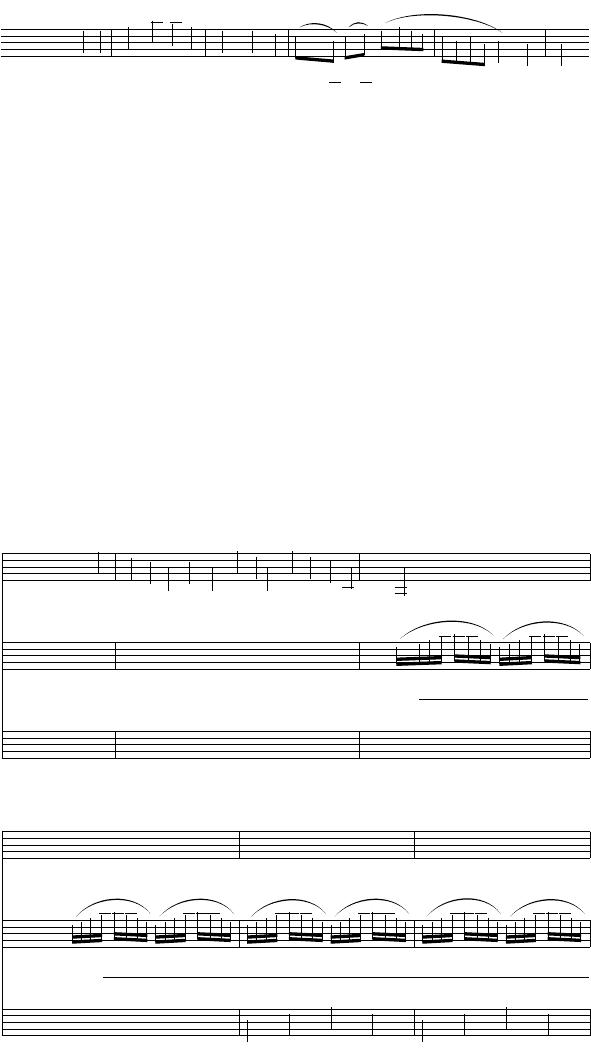

This brings me to a final question: how is musical irony used in op-

eretta? Irony is employed, of course, in the serious as well as the comic

domain. In serious opera, we usually find irony of situation rather than

irony communicated through music. Think of Delilah singing to Sam-

son of her love in Saint-Saëns’s opera. She wants him to believe it, and

it sounds like the truth to us, too, even though we know she hates him;

therefore, we perceive the irony of the scene. In musical communica-

tion, no less than verbal communication, there is no convention that

The Rift between Art and Entertainment 105

acts as a guarantee of sincerity. Language philosopher Donald Davidson

argues forcibly that the “ulterior purpose of an utterance and its literal

meaning are independent.”

105

There are examples of bitter irony in

tragic operas but, again, usually created by situation—think of the

party taking place at the very moment of Laura’s supposed death from

poison in La gioconda. The new departure for irony in operetta is that it

operates through a radical appropriation of stylistic conventions and

signs. The “wrong” musical sign is used to great ironic effect; in other

words, a song or aria may be double coded. An example is the martial

air sung by Général Boum in La Grande-Duchesse. The verse is single

coded: the bellicose words are given the appropriate musical signs, a

march rhythm and a melody containing fanfare-like intervals; but the

106 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 4.9 “He remains an Englishman,” H.M.S. Pinafore, act 2.

?#

#

c

.

J

œ

R

œ

He re

œ

œ

œ

œ

mains an English

˙

.

œ

J

œ

man! He re

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

mains an Eng

œ

rall.

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

J

œ

lish

˙

man!--- --- -

Example 4.10 Concern for Menelaus’s honor, La Belle Hélène (1864),

Finale, act 2.

&

V

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

4

3

4

3

4

3

c

c

c

R

œ

Hélène

Ah!

≈

≈

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

r

œ

r

œ

R

œ

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ

Qu'aije fait, ah! qu'aije fait de son de son hon

∑

∑

j

œ

‰Œ Ó

neur?

œ

Paris

œ

œ

(imitating violin)

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Ah!

∑

-

&

V

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

∑

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

(Ah!)

∑

∑

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

Agamemnon

‰

J

œ

(imitating cello)

‰J

œ

‰

J

œ

‰

∑

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

‰

J

œ

‰J

œ

‰

J

œ

‰

refrain is double coded: while the words tell of battlefield explosions

and assert the character’s military rank, the tune has the mannerisms

of a café-concert song, including an emphasis on the sixth degree of the

scale. The result is a deflation of the pomposity and violence of the

General’s language (ex. 4.11).

The possibilities for musical irony are many. Besides using the

wrong signs, there is the opportunity to use the right signs, but for

words that can scarcely bear the weight of those signs. For instance, the

music of “Tit Willow” from The Mikado never once suggests a knowing

smile at the ridiculous narrative. Then there is the typical parodic de-

vice of exaggeration. An example is the overblown patriotic style Sul-

livan uses for “When Britain Really Ruled the Waves” from Iolanthe

(1882). And that prompts me to end with a warning on the subject of

irony: some people never get it. Among them can be numbered those

who have interpreted this last song as an illustration of Sullivan’s bom-

bastic chauvinism. Thus, against all expectations, an audience may need

more critical engagement to understand the workings of operetta than

those of opera. This would accord, too, with Walter Benjamin’s convic-

tion that one of the most successful methods of stimulating critical

The Rift between Art and Entertainment 107

Example 4.11 “A cheval sur la discipline,” La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein

(1867), act 1.

?

&

?

#

#

#

4

2

4

2

4

2

R

œ

Général Boum

R

œ

A che

j

œ

œ

œ

f

‰

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

J

œ

J

œ

val sur la dis ci

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

pli ne,

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

œ

.

J

œ

R

œ

Par les val

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰

j

œ

‰

œ

lons

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰

---- -

?

&

?

#

#

#

‰

.

R

œ

REFRAIN

avec éclat

Et

œ

f

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

J

œ

J

œ

≈

R

œ

pif, paf, pouf, Et

œ

.

p

œ

.

J

œ

.

≈

R

œ

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

J

œ

≈

R

œ

ta ra pa pa poum, Je

œ

.

œ

.

œ

.

œ

.

J

œ

.

≈

R

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

R

œ

R

œ

suis moi le gé né

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

J

œb

(parlé)

J

œ

ral Boum Boum.

J

œ

j

œ

œb

b

>

j

œ

œ

>

J

œ

j

œ

œb

b

>

j

œ

œ

>

--

thought is through humor: “There is no better start for thinking than

laughter. And, in particular, convulsion of the diaphragm usually pro-

vides better opportunities for thought than convulsion of the soul.”

106

Operetta rejoiced in exposing the mechanics of its stage production

(or, one might say, in breaking frame), while “serious” opera became

more and more concerned with concealing them. The latter did so in

an attempt to create the illusionistic theatrical reality that Bertholdt

Brecht later wished to overturn, believing it encouraged passive wal-

lowing in a “reality” that, in some respects, might be linked to the “false

consciousness” the Frankfurt School condemned. Operetta is prepared

to reveal how the real is constructed as an illusion: in Utopia Limited,

Gilbert and Sullivan expose the stage illusion of “real” emotion by giv-

ing the tenor a song about the impossibility of singing when the emo-

tion that he feels actually exists as an offstage reality.

I could sing, if my fervour were mock,

It’s easy enough if you’re acting—

But when one’s emotion

Is born of devotion

You mustn’t be overexacting.

One ought to be firm as a rock

To venture a shake in vibrato,

When fervour’s expected

Keep cool and collected

Or never attempt agitato.

But, of course, when his tongue is of leather,

And his lips appear pasted together,

And his sensitive palate as dry as a crust is,

A tenor can’t do himself justice.

107

Folk Music: Edification for the Uncritical

One late nineteenth-century development, and its impact on aesthetic

debate, is yet to be considered. After midcentury, the education of taste

was seen as vital to the appreciation of music. For this reason, Manns

had introduced program notes at his concerts, and annotated programs

were also provided when the Philharmonic Society moved to St. James’s

Hall in 1858.

108

Theodore Thomas, who was based in New York, was

praised for his tours with an orchestra (which appears to have been

made up entirely of German players) and for setting a “standard of or-

chestral excellence” in order to “raise public taste as that it shall reach

the level of classic art.”

109

The trouble was, some began to think educa-

tion might not be enough. In line with that part of evolutionary dis-

course known as “recapitulation theory”—that the embryo evolving to

adulthood recapitulates the evolutionary stages through which a race

has passed—a Musical Times editorial foresees problems in bringing

108 Sounds of the Metropolis

highly cultivated music to people whose mental development has been

“handicapped in the struggle for existence by the law of heredity,” and

who have been “stunted morally and physically by their surround-

ings.”

110

Fortuitously, around the time this editor was expressing his

melancholy thoughts, an unexpected type of “easy-but-good” music

had sprung from English soil in the form of folk music.

Carl Engel, writing in the 1860s and 1870s on national song, had

accused English scholars of falling behind the rest of Europe in folk

song research; in return, later English researchers chose to “diminish

and distort” the role he had played in the folk song revival.

111

The En-

glish were certainly slow off the mark. Empress Elisabeth had been pre-

sented with a handsome bound volume of national melodies of the

Austro-Hungarian Empire on her marriage to Franz Joseph in 1854.

112

In France, in 1852, almost as soon as he came to power, Napoléon III

called for a collection of chansons populaires. This supposedly communal

art offered a vision of a more unified France, as well as “a pure, uncor-

rupted heritage.”

113

Politically conservative groups as well as utopian

socialists found qualities to admire in these chansons—at least, until

left-wing ideas began to gain currency among country folk. This inter-

est in national song signals, however, the beginnings of an ideological

schism that separated popular music that was created to make money

from another kind of “people’s music” that was believed to represent

the natural expression of a nation or race.

In England, William Chappell’s Collection of National English Airs

(1838) was a landmark publication in its historical concerns and its at-

tention to tunes, although it was not without an antecedent, the pub-

lication of the work of eighteenth-century collector Joseph Ritson in

1829. Importantly, Chappell had laid the foundation for his celebrated

later publication Popular Music of the Olden Time (1855–59), which was

hardly a work of folk song research but, in its comprehensiveness and

its inclusion of tunes, went far beyond anything achieved before.

114

However, its appeal was mainly to the middle class, evidenced by the

fact that it formed the substance of an evening entertainment by Miss

Poole at the Gallery of Illustration, Lower Regent Street—an establish-

ment so very respectable that it trembled even to call itself a theater.

115

Chappell himself was inclined to think of popular music in terms of

class rather than town and country, as when he informs us that “Early

One Morning” is one of “the most popular songs among the servant-

maids of the present generation.”

116

The term “folk music” served as a means of bracketing off a form of

people’s music that could be considered unsullied by commercial enter-

prise. At the first annual meeting of the English Folk Song Society, Hu-

bert Parry (who, significantly, was regarded as the leader of the English

Musical Renaissance) remarked on the superiority of folk song to music

hall song: the latter puts him in mind of “sham jewellery and shoddy

clothes” and is for people with “false ideals” who mistake “the com-

The Rift between Art and Entertainment 109

monest rowdyism” for the highest expression of human emotion. He

throws in an apparently casual comment about its being made “with a

commercial object,” but it is evident that the commercial aspect con-

tributes enormously to the disgust he feels. When Parry turns to folk

song, he stresses that it “grew in the heart of the people before they de-

voted themselves so assiduously to the making of quick returns.”

117

Cecil Sharp fervently hoped that folk song would oust coarse, commer-

cial popular song entirely; and one of its great advantages was that it

avoided the problem of having to educate people in its appreciation.

Now, one of the most remarkable qualities of the folk-song is its power

of appeal to the uncritical, to those who, unversed in the subtleties of mu-

sical science, yet “know what they like.” Its value lies in its possession of

this dual quality of excellence and attractiveness. Flood the streets, there-

fore, with folk-tunes, and those, who now vulgarize themselves and oth-

ers by singing coarse music-hall songs, will soon drop them in favor of the

equally attractive but far better tunes of the folk. This will make the streets

a pleasanter place for those who have sensitive ears, and will do incalcu-

lable good in civilizing the masses.

118

Sharp wished to make a distinction along German lines between

the “merely popular” song (volkstümliches Lied) and what had previ-

ously been referred to as “national” song but was now, he considered,

better designated by the term “folk-song.” However, the German term

Volkslied is not synonymous with Sharp’s definition of folk song—a

song “not made by the one but evolved by the many,” an anonymous

creation of the “common people” who have undergone no education or

training.

119

In contrast, the cover of Spina’s publication of Strauss Jr.’s

Erinnerung an Covent Garden, op. 329 (1868), describes these waltzes as

being based on English Volksmelodien, though they are a mixture of

music hall songs and drawing room ballads (“Champagne Charlie”

alongside “Home, Sweet Home”). Sharp is influenced by the pseudo-

science of race, believing folk song to be a “communal and racial prod-

uct” that “embodies those feelings and ideas which are shared in com-

mon by the race which has fashioned it.”

120

In putting together some concluding thoughts, the question arises:

was the schism between the “popular” and the “classical” created solely

by market conditions and the reaction to them, or were there other so-

cial and political factors at work? Tia DeNora suggests the possibility

that some of the old aristocracy in early nineteenth-century Vienna

embraced the new concept of greatness in music “as a proactive at-

tempt to maintain status in the face of the loss of exclusive control over

the traditional means of authority in musical affairs.”

121

Later in the

century, William Weber argues, the revolutions of 1848 “lent a power-

ful impetus to the hegemonic status of classical music,” since this music

was associated with morally uplifting and cosmopolitan cultural quali-

ties.

122

He remarks on the number of European choral societies that

were turning to the oratorios of Handel, Haydn, and Mendelssohn dur-

110 Sounds of the Metropolis

ing 1848–49. Nicholas Tawa sees 1830–70 as a period of stylistic transi-

tion to an indigenous American style, but Judith Tick shows that

women composers often bucked the trend, since female musical “ac-

complishment” meant something that resonated of the European salon,

not blackface minstrelsy.

123

A myth came to bedevil popular music: the idea that there is a for-

mula for popular success.

124

The editor of the Musical World in 1855 puts

down the success of the song “The Ratcatcher’s Daughter” (see chapter

7) to the “vitiated taste of the public.” His formula for a popular success

is that you must simply bear in mind that “people will always be led by

the ear, and the public ear must be pleased.”

125

But he soon begins to

contradict himself by recounting the different public tastes in evidence

at the opera house, the concert room, and the promenade concert.

Frederick Corder, writing in 1889, looks at the failure of an expected

hit and the unpredicted success of another piece and declares: “the

true reasons of popularity have ever been a secret and a mystery.”

126

Around this time, however, the early Tin Pan Alley firms of New York

thought that they had lighted on a formula for success, and today the

big corporations have not given up belief in its existence. Much of the

critical antagonism toward popular music in the twentieth century had

in the background an image of conveyor belts carrying prefabricated

sections to be bolted together before being delivered to a mass public of

passive consumers. As I write (in 2006), Mike McCready, the chief ex-

ecutive of Platinum Blue Music Intelligence, claims that he is able to

predict hits within twenty seconds using the firm’s database of previous

hits and a “spectral deconvolution” method of analysis that extracts forty

pieces of information about “deep structure.”

127

It is worth emphasiz-

ing that there has never been any scientifically substantiated evidence

to suggest that the key to popular success can be found solely in a par-

ticular kind of musical structure. The belief that structure is the source

of success neglects the importance of the social aspects of music, the

influence of friends and family, and the lifestyles people wish to lead.

The rift between art and entertainment widened in Vienna toward

the century’s close. The Theater an der Wien thought it could span the

gulf, and began to offer opera as well as its traditional fare of Spieloper.

In 1896–97, when it faced artistic and financial difficulties, the music

critic Richard Wallaschek warned it to make a choice between opera

and operetta, “given the complete separation that exists between these

genres today.”

128

This was the period when Vienna witnessed an in-

crease in learned articles on music, an emphasis on theory and analysis,

and a preference for abstraction and structural listening among erudite

musicians; it was, of course, home to Heinrich Schenker and Arnold

Schoenberg. Yet Hanslick, while holding popular dance music respon-

sible for a decline in intellectual effort on the part of listeners, hailed

Strauss Jr. after his death in 1899 as Vienna’s “most original musical tal-

ent,” and praised the Blue Danube as “a symbol for everything that is

The Rift between Art and Entertainment 111