Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

It continues in similar vein, but any suggestion of an inflammatory

call to engage in class struggle is defused by the chorus, which begins “I

wish I was a nob,” thereby suggesting that personal envy overrides a

sense of social injustice. Thus it was that British minstrels were able to

do a balancing act and appeal across classes even on the touchiest of

subjects. In the same year that the Mohawks gave their last perform-

ance, St. James’s Hall was destroyed by fire; its place is now taken by

the Piccadilly Hotel.

Frederick Corder gives a sour view of the later nineteenth-century

British minstrel show in an article in the Musical Times in 1885. He re-

lates that after a considerable period of absence abroad, he decided to

visit a London minstrel show to see if any of its former “quaint charm”

still survived. He describes seeing a thirty-strong “Christy” minstrel

troupe that was almost certainly the Moore and Burgess Minstrels. Al-

though one must make allowances for Corder’s scorn, his review is in-

teresting and unusual in providing information about the musical side

of the show.

162 Sounds of the Metropolis

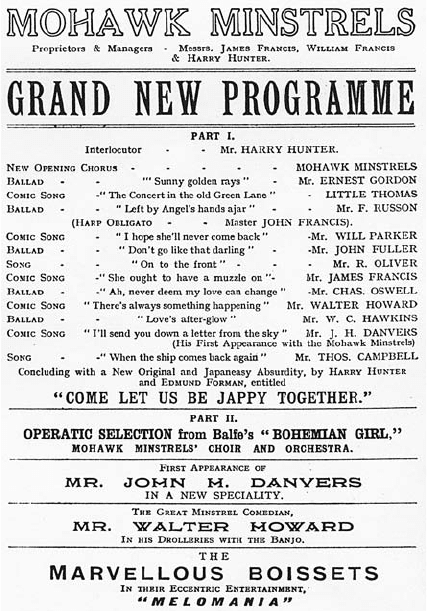

Figure 6.7 Program for the Mohawk Minstrels.

Well, the instrumental portion of the troupe was as follows:—two fiddles

and a cello, a flute, a cornet, a harp, and a big drum and cymbals, to which

were added ten pairs of bones and six tambourines. Imagine, if you can,

the effect of any orchestral piece whatever played by such a collection of

instruments. But no one could who had not heard it. A few odd periods

from one of Auber’s best known overtures were strung together, and this

prelude, though it lasted but a minute and a half, so completely deafened

me that I could hardly catch a word of the first two songs. One was a tenor

ballad, which seemed very touching, every fourth line ended with the

word “mother,” which was brought out with a jerk thus—“moth-a-ar,”

and affected the bystanders profoundly; indeed, I saw one poor woman in

tears, and was sorry to think that she should have perhaps her most sacred

feelings stirred by so coarse a touch. After each verse the chorus sang the

air harmonized (not over correctly), without accompaniment, the last time

in a whisper, which was a pretty effect, till I found it was done to nearly

every song, after which it became silly. I soon discovered that there were

only two kinds of songs; the sentimental, with whispered chorus, and the

grotesque comic, with the full force of the percussion instruments.

44

Black Troupes

Before the American Civil War, the most famous African-American per-

former was Master Juba. His real name was William Henry Lane, and he

has a claim to be acknowledged as the father of American tap-dancing.

45

His performances as “Juba” were greatly admired. Dance historian

Marian Hannah Winters has claimed that he was the “most influential

single performer of nineteenth century American dance.”

46

He made

his reputation in the early 1840s, and was hailed by Charles Dickens on

the latter’s visit to America as “the greatest dancer known.”

47

Juba had

been promoted by Barnum, who found him too pale, so he was blacked

up and given a woolly wig and bright red lips (the earlier convention,

before white was used for lips). This was also a practice not uncommon

for some later performers in supposedly authentic black troupes. Juba

performed as a dancer and tambourine player with Pell’s Serenaders at

Vauxhall Gardens in 1848. He danced the “Virginny Breakdown,” “Al-

abama Kick-up,” “Tennessee Double-shuffle,” and “Louisiana Toe-and-

Heel,” all of which the Illustrated London News took to be “Negro na-

tional dances.”

48

Juba broke many social taboos of the day. He toured—

as top of the bill—with white blackface performers in 1845, and settled

in England after marrying a white woman.

49

He was only twenty-seven

years old when he died in 1852.

The aftermath of the American Civil War and the abolition of slav-

ery had little effect on theatrical representations of African Americans.

Black troupes were formed, the first being the Georgia Minstrels in 1865.

They stressed the values of genuineness and authenticity, but since they

adopted the minstrel code, they continued to reproduce a simulacrum

of black culture and plantation life, all the more insidious for seeming

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 163

natural. Sam Hague brought his Slave Troupe of Georgia Minstrels to

England in June 1866. They were twenty-six emancipated slaves, and

performed for the first time on 9 July 1866, at the Theatre Royal, Liv-

erpool. They were not a great success. Hague thought the strength of

his company was their genuineness: they were the real thing. Audi-

ences, however, saw only what appeared to be a crude version of a

stage entertainment they thought was accomplished in a more pol-

ished and professional manner by blackface minstrels. A dejected Hague

paid for half of his troupe to return home and employed white per-

formers to make up the missing number. One successful black mem-

ber of the troupe was Aaron Banks, especially so when performing the

song “Emancipation Day.” Reynolds remarks, “No white man could

have put the same amount of enthusiasm and realism into this song.”

50

The comment reveals that the success of black minstrels was, indeed,

linked to recognition of their authenticity. Nevertheless, only in certain

moments, such as this, were black minstrels able to erase the stage from

the audience’s mind. Hague eventually took the lease of Liverpool’s St.

James’s Hall, but his company grew whiter with each passing year. In

the 1870s he had a separate touring company, and as evidence of the

popularity of minstrelsy, it has been estimated that he played to around

10,000 people a day during the first weeks of his Christmas season at

Birmingham’s Bingley Hall.

51

Barney Hicks’s Georgia Minstrels were another early all-black

troupe, and included Billy Kersands, inventor of the soft-shoe shuffle.

52

They became Callender’s Georgia Minstrels in 1872 and engaged

many exceptional performers, such as the comedian Sam Lucas.

53

They were taken over by J. H. Haverly in 1878, expanded to huge

size, and featured the celebrated banjoists the Bohee Brothers—one of

whom, James, gave banjo lessons to the Prince of Wales. Haverly em-

ployed the first commercially successful black songwriter, James Bland

(mentioned in chapter 2). Haverly toured Europe with what were

now the Colored Minstrels in 1881. One difference between black and

blackface troupes was that the latter avoided improvisation whereas

the former made use of it, especially in dancing. Haverly dominated

the minstrel scene in the 1870s. The mood of the time was for a grand

scale: his United Mastodon Minstrels were advertised as “Forty—40—

Count ’em—40—Forty.”

54

He had theatres in New York and Chicago,

went in for spectacle, and was not much concerned about historical

accuracy or cultural consistency. One of his shows was set in a Turk-

ish palace, but managed to include a scene of “basket ball.”

55

In 1894,

Primrose and West, who also favored extravagance, staged a “big min-

strel festival” with forty white and thirty black minstrels. Of course,

black and white were given separate slots in the show; an integrated

performance, unlike the mixed shows that had taken place in Britain,

was not tolerated in the United States. The final stage of minstrelsy

was reached when the Primrose and West troupes stressed artistry and

164 Sounds of the Metropolis

refinement, and sometimes chose to appear in the attire of the court

of Louis XI. The older style of minstrelsy was kept alive by Lew Dock-

stader, who was to coach Al Jolson.

People went to the blackface minstrel show to see a certain kind

of theatrical entertainment; they did not go to learn about African-

American culture. This inevitably meant that black troupes found them-

selves having to conform to blackface conventions in order to achieve

success. That does not mean that white audiences could not accept

black performers as anything other than minstrels. Minstrelsy was still

in its prime when the Jubilee Singers from Fisk University decided to

tour Europe. They arrived in England in 1873, and enjoyed an entirely

different reception from that given to black minstrels.

56

Here was a

group of black Americans introducing a novel genre, the Negro spiri-

tual, which raised no existing expectations on the part of their white

audiences. Religious music rarely featured in minstrel shows, so there

were no conventions to adhere to. The Jubilee Singers commented on

the lack of color prejudice they found in Britain, though Paul Gilroy

has cited evidence to the contrary.

57

Certainly, their reception could not

have been entirely free of the racial ideology that was growing in Eu-

rope and North America with every decade of the century.

The first collection of spirituals had been published as Slave Songs of

the United States (New York, 1867). Black spirituals invited metaphori-

cal interpretation: in “Go Down Moses,” old Pharaoh could seen as rep-

resenting the slaveowner, and frequent references to Canaan or to

“crossing over Jordan” might, in addition to being interpreted in a reli-

gious way, also mean the North and freedom from slavery. “Roll, Jor-

dan, Roll” appeared in the Slave Songs collection and also featured in

slightly different form in the Jubilee Singers’ repertoire. Its use of a flat-

tened seventh, and even a flattened third in its very first printed ver-

sion, as collected by Lucy McKim in 1862, would have confirmed those

features as characteristic of African-American music making (see ex.

6.10).

58

Black gospel took another leap into prominence after the Golden

Gate Quartet performed at Billy McClain’s huge show in Ambrose Park,

Brooklyn, in 1895.

Toward the end of the century, minstrelsy was being squeezed out

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 165

Example 6.10 “Roll, Jordan, Roll,” in G. D. Pike, The Jubilee Singers

(London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1874), 171.

&

b

b

b

4

2

œ

j

œ

J

œ

Roll, Jor - dan,

˙

U

roll,

œb

J

œ

J

œ

Roll. Jor - dan,

.

œ

J

œn

roll, I

&

b

b

b

.

J

œ

R

œ

.

J

œ

r

œ

want to go to

R

œb

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

œ

œ

Hea - ven when I die,

by vaudeville and ragtime musicals in America. Theatre owners were

putting together their own variety shows rather than renting out their

premises to visiting troupes. In Britain, minstrelsy faced the challenges

of Pierrot troupes (especially at seaside resorts) and variety entertain-

ment. It was a time when minstrel troupes had swollen in size and were

sometimes dressed bizarrely in court wigs and breeches. In the 1890s,

black American entertainers were abandoning minstrelsy in favor of the

Broadway musical. Ragtime songs became popular and were taken up

by both black and blackface performers. In England, Salford-born com-

poser Leslie Stuart developed a peculiarly British form of not-quite-rag-

time song, such as “Little Dolly Daydream” (1897) and “Lily of Laguna”

(1898). “Lily” is remarkable for its extended verse section, and its dis-

tant modulations—at one point a modulation from C minor to G minor

is succeeded by an abrupt switch to B-flat minor (see ex. 6.11). There

is little in the way of syncopation, but “blue” inflections (flattened

thirds) are found frequently. Ragtime songs were sung in England by

blackface performers like Eugene Stratton, as well as black performers

like Pete Hampton.

59

African-American music had little impact in nineteenth-century

Austria (despite tours by the Jubilee Singers and minstrel troupes).

60

The same was true of France (the Ethiopian Serenaders flopped in

Paris) until 1892, when the song “Tha-ma-ra-Boum-di-hé” arrived. It

has an infectious refrain that songwriter Henry Sayers took from the

singing of Mama Lou in a notorious St. Louis cabaret.

61

Originally en-

titled “Ta-Ra-Ra Boom-Der-É,” it had been published in New York the

previous year, and had already been made famous in England by Lot-

tie Collins, who performed it as a song and dance at the Grand Theatre,

Islington. Marguerite Duclerc then introduced it at the Ambassadeurs,

the large café-concert on the Champs-Elysées, and it took Paris by

storm. However, it was not the crest of a wave. Not only was Paris host

to a new style of cabaret at this time (see chapter 8) but France, like

Austria and Germany, already enjoyed a style of popular music that

fulfilled similar functions to that of minstrelsy in America and Britain:

Gypsy music. Tzigane music in France and Zigeunermusik in Austria

166 Sounds of the Metropolis

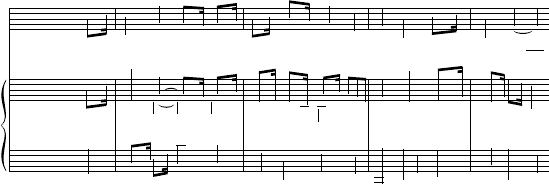

Example 6.11 “Lily of Laguna,” words and music by Leslie Stuart (London:

Francis, Day and Hunter, 1898), part of the verse.

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

c

c

c

.

œn

œn

ev' ry

.

œn

œn

œ

œ

œ

n

œ

œ

.

œ

œ#

.

œ

œn

sun down call in' in de

j

œ

œ

‰

œ

.

œ

œ#

.

œ

œn

œ œ œ

.

œ

œn

.

œ

œ

J

œ

‰

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œn

œ

œn

cat tle up de moun tain;

.

.

œ

œn

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

n

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

3

œ

œ

œn

.

œ

J

œ

œ

˙

.

œ

œb

I go 'kase she

j

œ

‰

˙

˙b

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

b

œ

œ

œ

œ

œb

œ

œ

œ

œ

n

œ

œ

.

j

œ

wants me,

.

.

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

J

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

-- - -

and Germany started to become popular around the same time as the

rise of minstrel troupes. The Romanian Cabaret that opened on the

Boulevard Montmartre during the Exposition Universelle of 1889 gave a

boost to the music in Paris. It led to Gypsy ensembles being engaged at

other establishments, such as the Restaurant du Rat Mort and, at the

turn of the century, Maxim’s. The same issues relating to authenticity

and cultural otherness apply.

The Viennese were certainly familiar with minstrelsy and the songs

of Stephen Foster. However, the style was never taken up with any

effort. Philipp Fahrbach Jr.’s quadrille Les Minstrels, op. 206, does not

identify any of the tunes, and they may be of his own invention, since

they make few gestures in the manner of minstrel style, and are for the

most part merely simple melodies with simple harmonic accompani-

ment (tonic, dominant, and subdominant). Symptomatic of the lack

of interest in minstrelsy in Vienna is that there is only a handful of

minstrel songs in the music collection of the Österreichische National

Bibliothek. Strauss Jr.’s Der Zigeunerbaron (1885) ensured that pseudo-

Hungarian Gypsy music would dominate the stage for many years, and

the popularity of this style delayed the conquest of Austria by jazz.

When the cakewalk was introduced in Vienna in 1903, it was soon

fashionable across the different classes and became associated with the

cultural and social values of modernity.

62

It was not until the 1920s,

however, that the battle for supremacy between African-American and

Gypsy styles was finally fought out in Austria, and the struggle contin-

ues to rage onstage in Emmerich Kálmán’s operetta Die Herzogin von

Chicago (1928).

Minstrel Contradictions

To accuse the blackface minstrel show of being simply racist would in-

vite the question why slavery was not found a fit subject for jokes. Many

minstrels were opposed to slavery, and some minstrel song composers,

like the Englishman Henry Russell and the American Henry Clay Work,

strongly so. Ironically, even the nineteenth century’s most famous an-

tislavery text, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), seems

at times closer to the minstrel show than the plantation; indeed, when

it circulated as a stage play it invariably included blacking up and min-

strel songs. It is unfair to chastise Stowe for that, when even Herman

Melville dishes up a minstrel-style stump speech for a black character

in chapter 64 of Moby-Dick, a work widely acclaimed as one of the great-

est American novels.

63

To add to the racial contradictions of minstrelsy, it had from the be-

ginning a strong Irish dimension.

64

In the American North, the African-

American and Irish working classes shared similar social conditions,

which sometimes led to fighting and at other times to friendships and

intermarriage. In addition, many important figures in minstrelsy were

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 167

Irish American, such as Stephen Foster, Dan Emmett, and George

Christy. This Irish side to minstrelsy was not ignored in England. Issue

number 14, volume 5, of the Mohawks Minstrels’ Magazine is described

as a “Special Irish Number.”

Among the questions the reduction of minstrelsy to racial issues

raises is “Would anybody practice the banjo for hours simply to make

fun of black banjoists?” John Boucher’s Glossary, published in London

in 1832, describes the banjo as a lower-class instrument.

65

In the 1850s,

a clergyman declared the banjo the best adapted of all instruments to

the “lowest class of slaves,” and “the very symbol of their savage degra-

dation.”

66

So why, a few decades later, do we find the future King Ed-

ward VII taking banjo lessons from black banjoist James Bohee? Young

“society ladies” in New York began to take up the banjo after Lotta

(Carlotta Crabtree), who could play the instrument well, became a the-

atrical star in the late 1860s.

67

By the 1890s, the high-class banjoist was

no rarity in Europe or the United States. The banjo, in addition to being

the subject of tuition books, was one of the first instruments to be the

subject of periodicals aimed at players. Banjo World was published in

London from 1893 to 1917, running to 271 issues.

Eric Lott has suggested that the early blackface performers were

genuinely attracted to black music making, but employed ridicule as a

result of white fears and anxieties. That contradictory behavior can be

accounted for by the mixture of fear and attraction found frequently in

encounters with cultural otherness. Lott maintains that, rather than

being its raison d’être, derision in blackface was a means of controlling

the “power and interest of black cultural practices.”

68

He stresses, as

does Eileen Southern, that minstrels did explore these practices, though

they were more likely to have pursued their research in urban bars and

theatres rather than on plantations.

69

In disgust at the racism of minstrelsy, it is tempting to relegate it

to the periphery of cultural history. There is no mention of blackface

minstrelsy in Ronald Pearsall’s Victorian Popular Music (1973).

70

Yet, in

avoiding minstrelsy, we neglect its role in the battle of ideas concern-

ing how people should live and what values they should espouse. Min-

strelsy certainly marginalized black concert musicians;

71

but we do not

remedy that by marginalizing those black popular musicians that were

involved with minstrelsy, such as composer James Bland and dancer

Billy Kersands. Moreover, studying minstrelsy forces us to consider

such questions as “What is black culture?” and “Who has the power to

define black culture?”

Theories of the carnivalesque adapted from Mikhail Bakhtin’s work

on Rabelais cannot furnish sufficient justification for admiring min-

strelsy, since the values being derided and inverted do not always, or

even most of the time, have as their satirical target the powerful in so-

ciety.

72

Issues of class are often well served, but not those relating to

ethnicity or gender, which are sometimes linked satirically together, as

168 Sounds of the Metropolis

in the stump speeches on women’s rights delivered by the blackface fe-

male impersonator. Jokes about big feet (to which, I should inform the

reader, I am personally sensitive) are hardly likely to start a revolution

against social injustice. How, then, should one listen to blackface min-

strelsy now? With one ear in the critical present, I would suggest, and

the other listening historically. Locating a pair of hermeneutic ears may

appear to be an awkward task, but media scholars have already found

the hermeneutic eyes that enable them to watch the old Carry On films

without wincing.

Minstrelsy allowed things to be said that could not be said in an-

other form, because the mask provided, metaphorically as well as liter-

ally, a cover. The social critique was perceived to emanate from a cul-

tural outsider who could not be taken as a genuine threat and, in any

case, was assumed to be just acting silly. In the same way, these all-male

troupes used female impersonators to say things that no respectable

woman could say. This still required careful assessment of the audi-

ence’s perceived sensitivities. In England, given minstrelsy’s predomi-

nantly bourgeois subject position, there were limits to the vulgarity of

the female impersonator. By contrast, in America they might complain

more knowingly on the subject of female rights, for example, proclaim-

ing suggestively that it wasn’t fair for women to be “always under

men.” No minstrel, once the burnt cork was removed, expected to have

to account for what he had said or done on stage.

73

The Minstrel Legacy

Minstrelsy was the catalyst for the unbridgeable rift between popular

and art song in the nineteenth century. Before blackface minstrelsy,

popular song had often been seen as diluted art song, but now there ap-

peared a kind of song, especially in the 1840s, that seemed to some the

antithesis of art song—which is not to say it was not enjoyed, even by

some of those who concurred with that estimation. In the early twen-

tieth century, blackface was absorbed into British variety entertain-

ment in the shape of performers like G. H. Chirgwin, Eugene Stratton,

and G. H. Elliott. There were some British women, too, who had shown

themselves not averse to blacking up, such as May Henderson. Later,

blackface emerged in film—in the first talkie, indeed, starring Al Jolson.

A favorite form of minstrel show humor was the “parade skit,” in

which one person after another enters the scene and confronts the per-

son on stage, who may be a bureaucrat in an office. Frank Sweet points

out the longevity of this humorous device, noting that it even featured

heavily in the Monty Python television series.

74

We also have to remind

ourselves that the minstrel trickster reappears in Disney’s animated

cartoons, not Jim Crow, perhaps, but Bugs Bunny.

It might be argued that the Virginia Minstrels set the pattern for the

pop band containing four young men, which reemerged in the late

Blackface Minstrels, Black Minstrels, and Their European Reception 169

1950s. Once again, the young men were white and leaned heavily on

the practices of black musicians. Rock-and-roll is not a million miles

from minstrelsy, as a quick comparison of “Old Dan Tucker” and Elvis

Presley’s early hit “Jailhouse Rock” (Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller,

1957) makes clear. Even the lyrics have parallels: both involve charac-

ters on the wrong side of the law. I noted earlier that twentieth-century

tap-dancing owes a debt to Master Juba, but in addition, dance histo-

rian W. T. Lhamon has shown that many of the dance moves made by

black dancers of the 1980s and 1990s, including those of Michael Jack-

son, can be directly related to minstrel show dance steps.

75

We could

broaden this out even more, perhaps, and argue that the whole idea of

incorporating gesture and bodily movement or dance into the perform-

ance of popular song has its roots in minstrelsy. It is something easily

overlooked, when this manner of performing popular song has become

the norm. Lhamon argues elsewhere that minstrel transgression con-

tinues in the performances of white rappers like the Beastie Boys. The

significant difference is that blacking up is no longer on the agenda,

since self-definition is now in the control of black artists.

76

Looking

back on how all this has come about, you may be embarrassed by the

role played by minstrelsy, or be offended by minstrels, or despise min-

strelsy, but you cannot ignore its impact on popular music.

170 Sounds of the Metropolis

7

The Music Hall

Cockney

Flesh and Blood,

or Replicant?

171

Despite its significance as the major form of working-class stage enter-

tainment over a sixty-year period, the music hall remains a neglected

area in musicology. Much of the scholarly work available tends to focus

on social and economic issues, which are usually linked to the troubled

relationship between popular culture and public morality.

1

Treatment

of music hall performance has been confined mainly to biographical

discussions of the stars of the halls, especially the lions comiques. In the

late 1980s, however, questions of performance and style, and the rep-

resentation of character types, such as the “swell,” formed the subject

of a few critical studies.

2

This chapter moves on from there to consider

not just parodic representation or character acting but the “imagined

real” of certain music hall characters. Leading the confusion of the real

and the imaginary in the 1890s was the portrayal on stage and in song

of the Cockney, often a costermonger (or, more familiarly, coster). These

were itinerant street traders who usually sold fruit or vegetables from

a donkey-drawn barrow (the name was derived from costard, a type of

apple). My argument is that from the 1840s to the 1890s the represen-

tation of the Cockney in musical entertainments goes through three

successive phases: it begins with parody, moves to the character-type,

and ends with the imagined real. In this final phase, the stage represen-

tation is no longer derived from the flesh-and-blood Cockney; instead,

it consists of a replication of an already-existing representation.

3