Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Phase 1: Parody

When Charles Dickens introduced the Cockney character Sam Weller

into his serialized Pickwick Papers in 1836, the impact was enormous; for

a start, sales increased a thousandfold over those for the previous issue.

The binders had prepared 400 copies of the first number, but “were called

on for forty thousand of the fifteenth.”

4

In consequence, the character

was to have a lasting effect on the representation of Cockneys elsewhere.

Many of the features of what became familiar as “literary” Cockney

language are already in place in the anecdote Sam Weller delivers on

his first appearance in Pickwick Papers:

“My father, sir, wos a coachman. A widower he wos, and fat enough for

anything—uncommon fat, to be sure. His missus dies, and leaves him four

hundred pound. Down he goes to the Commons, to see the lawyer and

draw the blunt—wery smart—top boots on—nosegay in his button-hole—

broad-brimmed tile—green shawl—quite the gen’lm’n. Goes through the

archvay, thinking how he should inwest the money—up comes the touter,

touches his hat—‘Licence, sir, licence?’—‘What’s that?’ says my father.—

‘Licence, sir,’ says he.—‘What licence?’ says my father.—‘Marriage li-

cence,’ says the touter.—‘Dash my veskit,’ says my father, ‘I never thought

o’ that.’—I think you wants one, sir,’ says the touter. My father pulls up,

and thinks abit—‘No,’ says he, ‘damme, I’m too old, b’sides I’m a many

sizes too large,’ says he.—‘Not a bit on it, sir,’ says the touter.—‘Think not?’

says my father.—‘I’m sure not,’ says he; ‘we married a gen’lm’n twice your

size, last Monday.’—‘Did you, though,’ said my father.—‘To be sure we

did,’ says the touter, ‘you’re a babby to him—this way, sir—this way!’—

and sure enough my father walks arter him, like a tame monkey behind a

horgan, into a little back office, vere a feller sat among dirty papers and tin

boxes, making believe he was busy. ‘Pray take a seat, vile I makes out the

affidavit, sir,’ says the lawyer.—‘Thankee, sir,’ says my father, and down he

sat, and stared with all his eyes, and his mouth vide open, at the names on

the boxes. ‘What’s your name, sir,’ says the lawyer.—‘Tony Weller,’ says

my father.—‘Parish?’ says the lawyer.—‘Belle Savage,’ says my father; for

he stopped there wen he drove up, and he know’d nothing about parishes,

he didn’t.—‘And what’s the lady’s name?’ says the lawyer. My father was

struck all of a heap. ‘Blessed if I know,’ says he.—‘Not know!’ says the

lawyer.—‘No more nor you do,’ says my father, ‘can’t I put that in arter-

wards?’—‘Impossible!’ says the lawyer.—‘Wery well,’ says my father, after

he’d thought a moment, ‘put down Mrs. Clarke.’—‘What Clarke?’ says the

lawyer, dipping his pen in the ink.—‘Susan Clarke, Markis o’ Granby,

Dorking,’ says my father; ‘she’ll have me, if I ask, I des-say—I never said

nothing to her, but she’ll have me, I know.’ The licence was made out, and

she did have him, and what’s more she’s got him now; and I never had any

of the four hundred pound, worse luck. Beg your pardon, sir,” said Sam,

when he had concluded, “but wen I gets on this here grievance, I runs on

like a new barrow vith the wheel greased.”

5

The characterizing features of Sam Weller’s language can be grouped

together as follows.

172 Sounds of the Metropolis

1. Addition, subtraction, and substitution of letters: for example,

“horgan” (organ), “babby” (baby), “gen’lm’n” (gentleman), “des-

say” (dare say), “arter” (after), “archvay” (archway), “inwest”

(invest).

2. Use of catch phrases or sayings: for example, “Dash my veskit”

(waistcoat); “struck all of a heap”; “I runs on like a new barrow

vith the wheel greased.”

3. Use of the present tense for the past: for example, “His missus

dies and leaves him four hundred pound”; “up comes the

touter.”

4. Use of nonstandard vocabulary (neologisms, metaphors, mala-

propisms, and dialect words): for example, “broad-brimmed tile”;

“draw the blunt.”

Backslang does not appear, nor the rhyming-slang so associated

with Cockney speech. Cockney humor is there in the association made

between roofs and heads—the reference to wearing a “broad-brimmed

tile.” Compare the examples of slang that Henry Mayhew cites in his

London Labour and the London Poor (1861) as being used by the coster-

mongers.

6

These show the common use of back-slang, which some-

times, though not always, changes a meaning to its opposite: for ex-

ample, a “trosseno” means not an honest sort (“onessort”) but a bad

sort of person (as “yob” now means a bad boy). They also offer insight

into Cockney humor—“do the tightener” means to go to dinner, that

is, cause one’s clothes to become tight at the waist. Dickens is restricted

in the use he can make of actual Cockney slang, because his middle-

class readers would not understand it; therefore, some phrases May-

hew cites are ruled out. In A Few Odd Characters out of the London Streets

(1857), Mayhew quotes a London costermonger speaking about his

use of language:

A penny ve calls a “yennep,”—a shilling is a “ginillhis,”—and a half-crown

a “flatch-enorc.” For “I’ve got not money,” ve says “I tog on yenom;” and

for “look at the policeman,” “kool the esilopnam.” A pot of beer, is “a top

o’ reeb” in our lingo; a glass of gin or rum ve dubs “a slag o’ nig or mur”:

and if you vos to ax me vot fammerley I’d got, vy, instead of telling on ye

as I’d “three boys and two gals besides the old ’ooman at home,” I should

say in reg’lar coster there vos “erth yobs and ote elrigs besides the delo

namow at emotch.”

7

It is to be wondered, even here, how much of this passage is May-

hew’s interpretation. He writes “girls” phonetically as “gals,” for in-

stance, yet the backslang version “ote elrigs” would appear to establish

that the costermonger is guided by received pronunciation when using

backslang.

Dickens, who had less reason than Mayhew to strive for accuracy,

may have invented some features of Cockney language and character,

The Music Hall Cockney 173

while he no doubt exaggerated other features: for example, the extent

to which an initial w is replaced by v, and vice versa.

8

We also have to

bear in mind that Dickens was not writing for a Cockney readership. A

literate Cockney would not, after all, require special Cockney spellings.

Moreover, there is often a moral prejudice at work when Dickens

writes nonstandard English. The description for this used to be “sub-

standard English,” a phrase that could easily suggest that it might be ac-

companied by substandard morals: this helps to explain why some of

Dickens’s characters, like the good Oliver Twist, unaccountably resist

what may be interpreted as the “corruption” of the street vernacular.

Even a middle-class character who uses slang, like James Harthouse in

Hard Times, demonstrates a tendency to moral weakness (Harthouse’s

“idle” use of language is symptomatic of his indolent life; he is contin-

ually “going in” for things but lacks application).

Now let us examine an example of parodic representation in song:

“The Ratcatcher’s Daughter,” a “serio-comic ballad” that enjoyed im-

mense success in the 1850s. A correspondent to the Musical World in

1855 declares: “Everywhere I go in London . . . I cannot escape the

infliction of having my ears stunned with some hideous words relating

to the daughter of a ratcatcher and a seller of sand, set to a most vile

tune.”

9

The song was also being advertised in the New York Musical

World with not a little exaggeration as the “greatest comic song of the

age . . . sung throughout England and Scotland by everybody from

Queen to Peasant.”

10

It purports to be a tale of costermonger romance

and tragedy sung by a Cockney. The words, in fact, issued from the pen

of the Reverend Edward Bradley;

11

the music (headed with the expres-

sion mark comicoso con jokerando) is attributed to the comedian Sam

Cowell (1820–64).

12

Cowell was born in London but, from the year

after, grew up in America, where he gained his acting experience.

13

He

returned only in 1840 and, later that decade, made this song popular at

Evans’s Song and Supper Rooms. These formed part of a hotel located

in Covent Garden, an area where costermongers were a common sight,

thus enabling patrons of Evans’s to make an on-the-spot comparison

between the real and the parody. Costermongers may have set up their

barrows or gone to collect food in London’s West End, but this was not,

of course, a Cockney area of the city. Those were the East End and

across the Thames in Lambeth; both places were inclined to assert that

they were home to the genuine Cockney. The Song and Supper Rooms

of the 1830s and 1840s, whether in Covent Garden or in and around

the Strand, cannot be considered remotely working-class in character

or clientele, although some of the performers there were later to make

the transition to the stages of the more socially varied and geographi-

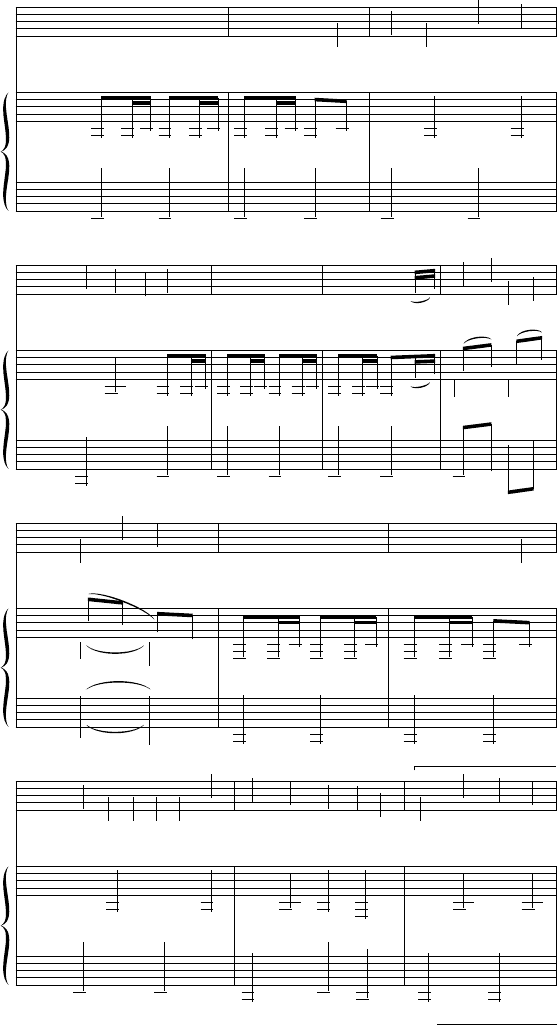

cally dispersed music halls. The tune and first two verses of “The Rat-

catcher’s Daughter” are given in ex. 7.1.

Repeating the previous taxonomy of Cockney features, a lyric analy-

sis of the complete song reveals the following.

14

174 Sounds of the Metropolis

1. Addition, subtraction, and substitution of letters: for example,

“haccident,” “’at,” “nuffink,” “arter,” “Vestminstier,” “woice.”

2. Use of catch phrases or sayings: for example, “bunch of carrots”;

“cock’d his ears”; “dead as any herrein’” (herring).

3. Use of the present tense for the past: for example, “so ’ere is an

end of Lily-Vite Sand.”

The Music Hall Cockney 175

Example 7.1 “The Ratcatcher’s Daughter,” words by the Reverend

E. Bradley, music attributed to Sam Cowell (London: Charles

Sheard, 1855).

4. Use of neologisms, malapropisms, and dialect words: for example,

“putty” (pretty); and in the spoken passage after the last verse,

“resusticated,” “seminary” (cemetery).

No reality effect is achieved by the lyrics of this song, for a variety

of reasons: first, because of its satirical character (for example, the ref-

erence to her “sweet loud woice”); second, because of the random way

it drops an initial h (for example, “hat” is in the first verse, “’at” in the

second); third, because of the mechanical way it exchanges an initial v

for w (which highlights a glaring inconsistency in verses 8 and 9, where

“what” appears in the former and “vot” in the latter); and fourth, be-

cause of its mocking or patronizing use of malapropisms, like “semi-

nary” for “cemetery.” One expression, “t’other” (for “the other”), stands

out oddly, since it is normally associated with the speech of West York-

shire. Sam Cowell, as the singer, would have been constructing a work-

ing-class persona for the audience not to laugh with but, rather, to

laugh at. Another Cowell song, “Bacon and Greens,” reveals the social

class of the audience he expects to be performing to in the unidentified

musical quotations used for its interludes. There would be no point

choosing quotations that would go unrecognized (they are Bishop’s

“Home, Sweet Home,” Haynes Bayly’s “Long, Long Ago,” and Balfe’s

“The Light of Other Days”). It need hardly be added that the musical

style of “The Ratcatcher’s Daughter” is itself more redolent of the draw-

ing room than the street; this “polite” musical character, indeed, en-

hances the humorous effect by contrasting incongruously with the

“vulgarity” of the Cockney words.

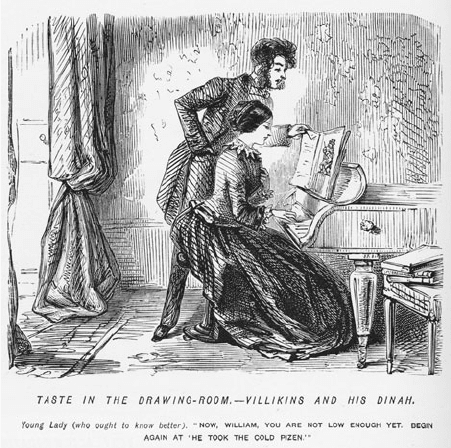

Another example of the Cockney parody song is “Villikins and His

Dinah,” which was sung by Frederick Robson as the character Jem Bags

in a “comedietta” at the Olympic Theatre entitled The Wandering Min-

strel (1853).

15

It was again made famous by Sam Cowell.

16

The Villikins

of the title is offered as a Cockneyfied version of the name William, but

that there is nothing particularly Cockney about the tune in terms of

topography or style is evident from its being known in the United

States as the melody of “Sweet Betsy from Pike.” A selection of words

and phrases will give its flavor: “wery,” “siliver,” “parient,” “consik-

vence,” “inconsiderable” (malapropism for “inconsiderate”), “diski-

very,” “unkimmon nice,” “mind who you claps eyes on.” A Punch car-

toon of 1854 depicts a middle-class couple trying to capture the spirit

of this “low” language (fig. 7.1).

It is instructive to compare these parodic songs with “Sam Hall,” a

ballad the Scottish entertainer W. G. Ross adapted from the earlier

“Jack Hall.”

17

He made it famous at the Cyder Cellars, one of the West

End’s less salubrious venues, located at No. 20 Maiden Lane (which

runs parallel to the north side of the Strand).

18

Melodramatic in its

cursing and brutality, it has little in common with the songs so far dis-

cussed. However, we need to find out what was taking place in venues

176 Sounds of the Metropolis

that were even further downmarket to obtain an idea of what coster-

mongers were watching and listening to at this time. Evidence, admit-

tedly in prejudiced form, can be gleaned from the journalist James

Ritchie’s description of a costermongers’ “Free and Easy,” a singsong in

the concert room of a public house:

I once penetrated into one of these dens. It was situated in a very low

neighbourhood, not far from a gigantic brewery, where you could not

walk a yard scarcely without coming to a public house. . . . Anybody sings

who likes; sometimes a man, sometimes a female, volunteers a perform-

ance, and I am sorry to say it is not the girls who sing the most delicate

songs. . . . One song, with a chorus, was devoted to the deeds of “those

handsome men, the French Grenadiers.” Another recommended beer as a

remedy for low spirits; and thus the harmony of the evening is continued

till twelve, when the landlord closes his establishment.

19

Further insight is provided by Henry Mayhew’s account of a

“penny gaff,” in this instance, a public entertainment taking place on a

small stage in a converted room above a warehouse:

The “comic singer,” in a battered hat and . . . huge bow to his cravat, was

received with deafening shouts. Several songs were named by the costers,

but the “funny gentleman” merely requested them “to hold their jaws,”

and putting on a “knowing” look, sang a song, the whole point of which

consisted in the mere utterance of some filthy word at the end of each

The Music Hall Cockney 177

Figure 7.1 Cartoon (1854) by John Leech, in John

Leech’s Pictures of Life and Character from the Collection of

“Mr. Punch” (London: Bradbury, Agnew, 1886), 250.

stanza. Nothing, however, could have been more successful. . . . The lads

stamped their feet with delight; the girls screamed with enjoyment. When

the song was ended the house was in a delirium of applause. The canvass

front to the gallery was beaten with sticks, drum-like, and sent down

showers of white powder on the heads in the pit. Another song followed,

and the actor knowing on what his success depended, lost no opportunity

of increasing his laurels. The most obscene thoughts, the most disgusting

scenes were coolly described, making a poor child near me wipe away the

tears that rolled down her eyes with the enjoyment of the poison.

20

To summarize phase 1, the subject position of the parodic Cockney

song was middle class. It was influenced in its language by Dickensian

Cockney, and in its music by bourgeois domestic song. It represented

Cockneys as figures of fun for those who had little cultural understand-

ing of working-class Londoners. Consequently, these songs that sup-

posedly issued from the mouths of Cockneys bore no relation to what

was happening in pubs and penny gaffs of the East End.

Phase 2: The Character-Type

In the 1860s, the Cockney becomes one among several character-types

available to the music hall performer; others can be, for example, Irish,

blackface, rustic, or a city “swell.” The character-type differs from the

parodic Cockney in that he or she is no longer viewed through a satir-

ical lens. This is not to deny that character-types can slip easily into

stereotypes. An important feature to note during this phase, however,

is that the identity of the performer is not confused with that of the

character. The performer is unmistakably acting a role on stage, as Harry

Clifton played the part of a brokenhearted Cockney milkman in one of

the enduring songs of this decade, “Polly Perkins of Paddington Green.”

21

Alfred Vance (real name Alfred Peck Stevens, 1839–88), one of the

lions comiques, was the first to represent the coster on the music hall

stage.

22

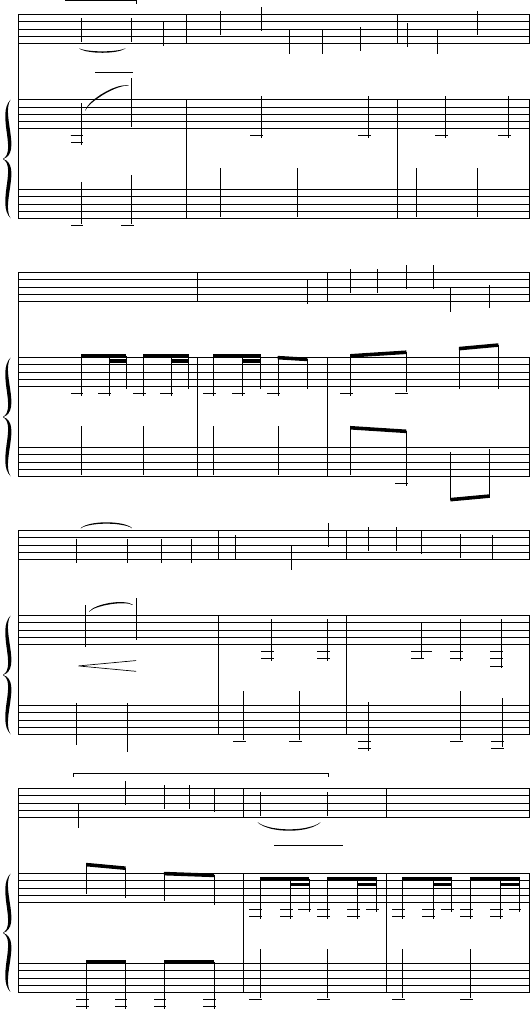

His “The Ticket of Leave Man” (1864) is very different from

“The Ratcatcher’s Daughter” in both its lyrics and its Jewish melodic

and rhythmic character (see ex. 7.2).

23

The presence of Jewish ele-

ments should come as no surprise, given that Mayhew, basing his

figures on calculations by the chief rabbi, had estimated the number of

Jews living in London at midcentury as 18,000.

24

A later survey sug-

gests that the figure may have been around 25,000.

25

The majority of

the Jewish working class lived in the East End, especially in or near

Whitechapel. There had been in existence there, at least since the

1880s, a Jewish Working Men’s Club with a license for music and a

seating capacity of 640.

26

The overall population of Whitechapel was

73,518 when Charles Booth was writing in 1891;

27

but by then many

more Jews had arrived (London’s Jewish population, native and for-

eign born, increased to 140,000 by 1900). One might speculate as to

178 Sounds of the Metropolis

The Music Hall Cockney 179

Example 7.2 “The Ticket of Leave Man,” excerpt, words by A. G.

Vance, music by M. Hobson (London: Hopwood and Crew, c. 1864).

&

&

?

#

#

#

4

2

4

2

4

2

∑

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

Œ‰

J

œ

I've

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

J

œ

j

œ

j

œ

just come back from

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

&

&

?

#

#

#

j

œ

r

œ

r

œ#

j

œ

‰

Aus - tra - li - a,

‰j

œ

œ

œ

#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

∑

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

ƒ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

Œ‰

œ

œ

As

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

j

œ

J

œ

J

œ

you can ea - sy

œ

P

œ

œ

œ

œ œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

&

?

#

#

#

J

œ

j

œ

j

œ

‰

se - e - e,

œ

œ

œ

œ#œ#

J

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

‰

∑

œ

œ

#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

ƒ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

Œ‰

J

œ

Sent

œ

œ

#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

&

&

?

#

#

#

j

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

R

œ

j

œ

out for the be - ne - fit

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

P

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

U

R

œ

U

R

œ

of my 'ealth, Wer-ry

‰j

œ

œ

œ

#

j

œ

œ

œ

U

j

œ

œ

œ

#

U

j

œ

œ

rit.

‰

j

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

J

œ

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

kind treat -ment to

‰j

œ

œ

œ

#

‰j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

(continued)

180 Sounds of the Metropolis

&

&

?

#

#

#

œ

j

œ

j

œ

me; They

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

j

œ

R

œ

R

œ

J

œ

thought a "ten - ner" would

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

J

œ

J

œ

j

œ

‰

do me good,

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

&

&

?

#

#

#

∑

œ

œ

ƒ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

Œ‰j

œ

I

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ

r

œ

J

œ

J

œ

was as well as I could

œ

œ

œ

P

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

&

&

?

#

#

#

œ

J

œ#

U

R

œ

R

œ

be, But they

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

#

U

‰

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

U

‰

œ

J

œ

j

œ

gave me a

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

r

œ

r

œ

j

œ

j

œ

U

J

œ

U

"tic - ket of leaf" Vich

‰j

œ

œ

œ

#

j

œ

œ

œ

U

j

œ

œ

œ

#

U

j

œ

œ

rit.

‰

j

œ

œ

u

j

œ

œ

u

&

&

?

#

#

#

J

œ

j

œ

r

œ

r

œ

j

œ

vos the tic - ket for

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

>

œ

œ#

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰

me.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

ƒ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

∑

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

j

œ

œ

‰

(Relative major)

Example 7.2 Continued

whether or not Cockney backslang owes anything to the fact that He-

brew is read from right to left, in other words, backward compared to

English.

28

Certainly, in a Cockney backslang expression like “esilop” for

“police,” it is a reversal of how the word is read rather than how the

word sounds (which would have produced “seelop”). Interestingly, the

Cockney music hall performer Charles Coborn sings the chorus of his

well-known “Two Lovely Black Eyes” in several languages, including

Hebrew, on a record he made in 1904.

29

Until they began to be undersold by poor Irish immigrants, Jew-

ish street traders had almost a monopoly on the sale of oranges and

lemons, the former fruit being as popular in music halls then as pop-

corn is in cinemas today. More than anything, perhaps, Jews were as-

sociated with clothes and tailoring, providing the “slap-up toggery” for

a Cockney night out or Sunday jaunt. Because of the strength of the

Jewish community in the East End, the Jewish Cockney was a well-

known character. The father of a popular songwriter of the 1930s,

Michael Carr (born Maurice Cohen), for example, was a boxer known,

significantly, as “Cockney Cohen.” Whether being a Jew or being a

Cockney came first was probably no more an issue than whether, say,

on Merseyside being a Catholic came before being a Scouser (Liver-

pudlian).

It is difficult to find contemporary Jewish secular music to com-

pare with Vance’s “Ticket of Leave.” One of the melodies for Hallel,

however, has several points of resemblance and was published in a

collection of music of the Sephardic liturgy seven years before Vance’s

song appeared (see ex. 7.3).

30

Sephardim were originally the domi-

nant Jewish community in Whitechapel but, as they became affluent,

began to leave the area. Their place was taken, in the main, by Ashke-

nazim from Poland and Russia. I also offer, perhaps less reliably, an ex-

ample of a traditional Jewish folk song, “Ale Brider” (We are all broth-

ers), because of the interesting comparison it provides with Vance’s

song (see ex. 7.4).

It will be noted that most of the melodic material of all three occurs

between the tonic and fifth above, that minor gives way to relative

major, and that they all feature a melodic stepwise descent from fifth to

tonic. The latter is most striking at the final cadences of examples 7.2

and 7.4 (see bracketed passages), which also share in common a 2/4

rhythm and vigorous accompaniment.

31

Vance’s song’s kinship to a

Jewish musical style is not flattering, however: the singer is a Cockney

member of the criminal fraternity: to be given a “ticket of leave” was to

be released on probation.

Vance’s coster representations met with resounding success from

the moment he introduced his coster songs, like “The Chickaleary

Cove,” on the music hall stage in the 1860s. However, it should be

borne in mind that he was not just a Cockney character actor or coster

The Music Hall Cockney 181