Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Bruant’s coldness prevented his song from being seen as sentimen-

tal. His concern with social injustice was heightened by singing in the

first person, suggesting personal involvement, though the “I” of the

songs is usually another narrative voice rather than Bruant himself.

Surprisingly, perhaps, given Bruant’s strongly masculine persona (see

fig. 8.1), the narrative voice in “A la Villette” is feminine (though if his

recordings are anything to go by, he omitted the stanza with the line “I’

m’app’lait sa p’tit’ gigolette”). Having lived near Mazas prison and visited

it regularly, he acquired knowledge of criminal language and behavior.

The overall effect was one of authenticity, his listeners feeling that his

songs “take the real life of poor and miserable and vicious people, their

real sentiments . . . and they say straight out, in the fewest words, just

what such people would really say, with a wonderful art in the reproduc-

tion of the actual vulgar accent.”

31

Yet we may wonder how that recep-

tion squared with the theatricality of the red scarf, big hat, and cape.

Bruant’s costume indicated a theatrical frame for his performance,

reassuring his listeners that it was, after all, an act. Francis Carco sug-

gests that Bruant’s audience was seeking sensation: “the fine ladies

shuddered with horror, without doubting that Bruant, after having

troubled them, would laugh about it.”

32

Hawkins, following a line sim-

ilar to Carco, proposes that Bruant’s songs appealed to the bourgeoisie

because they were “tales from the other side of the tracks,” inspiring “a

sentiment of gratitude for the security of the bourgeois lifestyle” while

allowing them to enjoy “the thrill of imagining themselves in touch

with the dangerous life of the streets.”

33

The rudeness with which he

often addressed directly individual patrons, and which he had inherited

from Salis, added to the engrossment of his audience. As Erving Goff-

man explains of audience-insulting routines: “the recipient of the

frame-breaking remark is forced into the role of performer, forced

sometimes to project a character. He, in consequence, floods out, and

this provides a source of involvement for the remaining members of

the audience.”

34

Bruant’s theatrical frame was, in fact, loosely applied. He walked

up and down while singing, thus avoiding a set space, such as a stage

or platform that would delineate a represented world separated from a

202 Sounds of the Metropolis

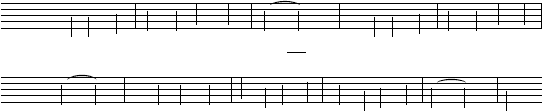

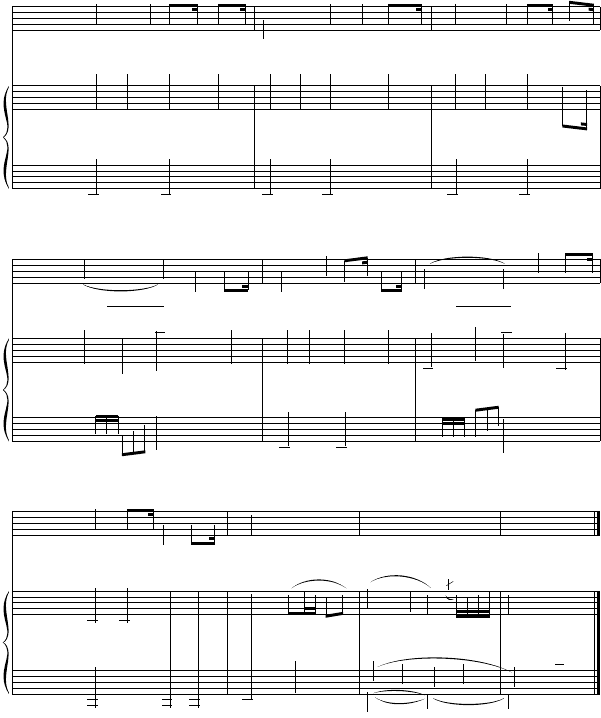

Example 8.2 “A la Villette” (1885), words and music by Aristide

Bruant.

&

b

b

8

6

Andantino

J

œ œ

J

œ

Il a vait

œ

J

œ

œ

J

œ

pas en cor' vingt

.

œ œ

‰

ans,

Œ

J

œ œ

J

œ

I' con nais

œ

J

œ

œ

J

œ

sait pas ses pa-- -- -

&

b

b

.

œ œ

‰

rents,

Œ

J

œ œ

J

œ

On l'ap p'lait

œ

J

œ

œ

J

œ

To to La ri

œ

J

œ

œ

J

œ

pette, A la Vil

.

œ

.

œ

let

œ

U

te.---- --

real world. Yet one could argue that the Mirliton itself was his stage set.

In this regard, it is significant that when he was asked to perform at the

Ambassadeurs and the Eldorado, he agreed to do so only if the Mirli-

ton were recreated on stage. Bruant also adopted practices typical of

real-life social communication that enhanced the perception of the au-

thenticity of his characterizations. It was not just his frequent use of the

first person, or the sense that he knew personally the characters he

sang about; it was his use of slang and casual references to working-

class mores delivered with the implication that he need not explain

himself. At the same time, he needed to ensure, as did the Cockney

singers discussed in chapter 7, that his audience could follow him. Like

the music hall costers, he avoids backslang, for example, le verlan, a

form of French prison slang that typically reverses the order of syllables

(verlan is derived from envers). He made sure he gave listeners enough

intelligible vocabulary to help them follow the narrative, as can be seen

in the excerpted verses from “A la Bastoche” (ex. 8.3).

Verse 1

Il était né près du canal,

Par là . . . dans l’quartier d’l’Arsenal,

Sa maman qu’avait pas d’mari,

L’appelait son petit Henri . . .

Mais on l’appelait la Filoche

A la Bastoche. . . .

Verse 5

Un soir qu’il avait pas mangé,

Qu’i’rôdait comme un enragé;

Il a, pour barbotter l’quibus,

D’un conducteur des Omnibus,

Crevé la panse et la sacoche

A la Bastoche.

Verse 1

He was born by the canal,

over there . . . in the Arsenal district.

His mother, who hadn’t a husband,

called him her little Henry. . .

But they called him the shirker

at la Bastoche. . . .

Verse 5

One evening when he hadn’t eaten

and was prowling around like a madman,

he punctured both the belly and the bag

of a conductor of the local trains

in order to steal money

at la Bastoche.

35

No Smoke without Water 203

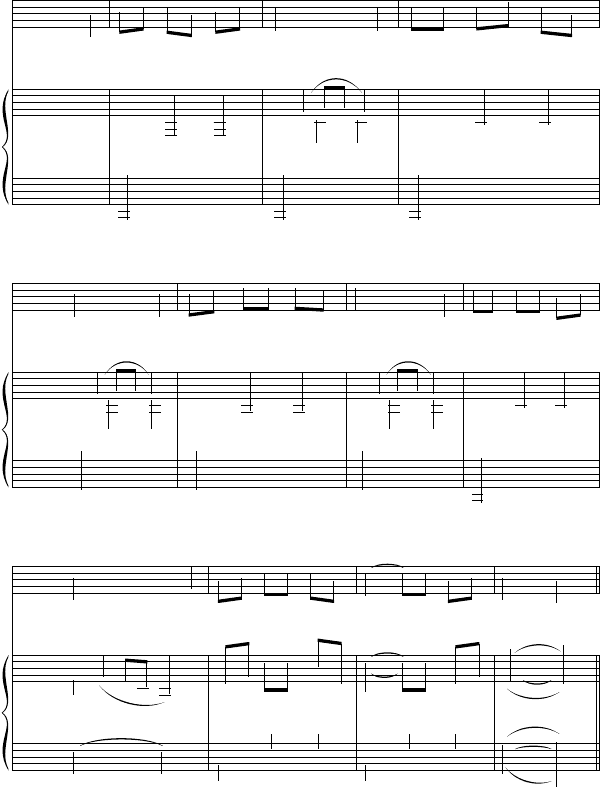

Bruant’s chanson “A la Bastoche” has a structure of four two-

measure phrases followed by one three-measure phrase (with an ac-

celerando), which makes for a satisfying sense of completeness. How-

ever, the fast interludes in a different meter are a puzzle. These appear

to quote the melody of one of his wryly humorous chansons, “Belleville-

Ménilmontant,” but the purpose is unclear—it may be there merely in

order for its jollity to make an ironic and dramatic contrast with the

mood of the verses. Beyond the thought given to phrasing, the piano

accompaniment is, as usual, very basic, and the song melody itself has

204 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 8.3 “A la Bastoche” (1897), words and music by Aristide Bruant.

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

4

3

4

3

4

3

J

œ

Il

‰

‰

œ

œ œ

œ

œ

œ

é tait né près du ca

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

˙

‰

J

œ

nal, Par

‰

j

œ

œ

œb

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œ

œ œ

œ

œ

œ

là... dans l'quar tier d'l'Ar se

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

-- ---

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

˙

‰

J

œ

nal, Sa

‰

j

œ

œ

œb

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œ

œ

œ œ œ

œ

ma man qu'a vait pas d'ma

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

˙

‰

J

œ

ri, L'ap

‰

j

œ

œ

œb

œ

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œ

œ œ œ

œ

œ

pe lait son pe tit Hen

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

-- - -- --

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

˙

‰

j

œ

ri... Mais

‰j

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

‰

˙

˙

J

œ

‰

œ

œ

œ œ œ

œ

on l'ap pe lait la Fi

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ œ

.

˙

œœœ

œ

œ

lo che A la Bas

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ œ

.

˙

˙

J

œ

to che.

˙

˙

˙

j

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

J

œ

œ

œ

-- - - - -

no carefully shaped structure (for example, it lacks internal symmetries)

and suggests something originally improvised as a vehicle for the words.

These seem to demand a three-quaver anacrusis rather than the exist-

ing one quaver with the other two pushed into the following measure;

however, French does not require the same kind of stress as English,

and thus the issue of verbal stress coinciding with musical accent is not

the same. The skeletal melody resembles the kind often found in the

work of amateur songwriters and invites an improvisatory flexibility

when sung.

36

Yet whatever corners have been cut musically, the words

have been given considerable thought, and have been carefully struc-

tured to provide the desired narrative pace, as well as to lead back to

the first stanza at the end, with its suggestion of the youth having been

doomed from the beginning and of a fresh cycle of misery beginning for

those born by the canal.

37

“The Bastoche” is a vernacular term for the

Bastille district. Little Henri is not the sort to excite sentimental sympa-

thy; yet Bruant does elicit our empathy for the brutality and poverty of

the lives of the unfortunates he sings about. This is partly achieved by

the contextualized portraits he paints of his characters, often incorpo-

rating details of childhood and parents (or their absence) into the char-

acter’s past history.

Other Cabaret Artists

Jules Jouy (1855–97) was in many ways closest to Bruant in his reper-

toire. He wrote topical and political songs that he sang to his own piano

accompaniment at the Chat Noir and, later, at its rival the Chien Noir

(created by Victor Meusy with other Chat Noir performers in 1895) and

at his own Cabaret des Décadents (opened 1893). His “La Veuve” (1887)

became a well-known antiguillotine song. In 1886, Jouy reworked Jean-

Baptiste Clément’s song “Le Temps de cerises” (“Cherry Time”) as “Le

Temps des crises” (Crisis time).

38

In doing so, he made a more overtly po-

litical statement out of a song that had earlier been a favorite of the Com-

munards of 1871, who interpreted the return of spring as a metaphor

for the return of liberty.

It should not be assumed, however, that all cabaret performers

chose the same themes. The postal employee Maurice Mac-Nab (1856–

89) sang ironic songs of working-class life at the Club des Hydropathes,

then with the breakaway group the Hirsutes. He enjoyed his first suc-

cess as an auteur-interprète (author-performer) in the basement of the

Café de l’Avenir. He specialized in macabre and grotesque songs, such

as “Suicide en partie double,” in praise of double suicides;

39

and “Les

Fœtus,” in which he concludes that aborted fetuses enjoy the singular

good luck of being dead before they are born. The subject matter of this

chanson certainly points to the sometimes striking difference in reper-

toire between the cabaret and the café-concert, and the effect of the

text being set as a waltz melody is bizarre (ex. 8.4). One of his milder

No Smoke without Water 205

satires that reached a wider audience was “Le Pendu,” in which a hang-

ing man dies while one person after another calls for someone to help

in the emergency. Mac-Nab also sang chansons with anarchist sympa-

thies, like “L’Expulsion.” Michel Herbert describes him as the leader of

the topical chansonniers.

40

Ill health forced him to give up performing,

and he died of tuberculosis at the early age of thirty-three.

He sang with a piano accompaniment, and his voice was of a mem-

orable, if not very musical, character:

Mac-Nab possessed the most hoarse and out of tune voice that it is possible

to imagine; it was like listening to a seal with a cold. But that bothered him

little. He sang all the same, without worrying about the desperate gestures

of Albert Tinchant, his usual accompanist.

41

A favorite Mac-Nab political-satirical chanson at the Chat Noir was “Le

Grand Métingue du Métropolitain,” which celebrates the strike by metal

workers at Vierzon (Mac-Nab’s birthplace, near Bourges) in 1886. It

pokes fun at the municipal police, and makes ironic use of phrases as-

sociated with appeals to patriotism.

206 Sounds of the Metropolis

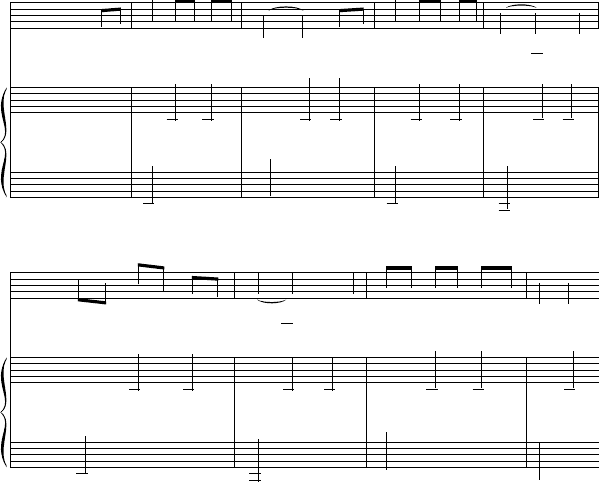

Example 8.4 “Les Fœtus” (1892), words by Maurice Mac-Nab, music by

Camille Baron.

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

4

3

4

3

4

3

œ

Andantino

œ

On en

Œ

Œ

œœœ œ œ

voit de pe tits de

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œ

J

œ‰

œ

œ

grands, De sem

Œ œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œœœ œ œ

blab les, de dif fé

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œ

J

œ

‰‰

J

œ

rents, Au

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

-----

&

&

?

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

b

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

fond des bo caux tran spa

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œ

j

œ

‰‰

j

œ

rents. Les

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œ

œ œ œ œ œ

uns ont de fi gu res

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

ŒŒ

œ

J

œ

dou ces;

Œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

Œ

--- -- -

Verse 1

C’était hier, samedi, jour de paye,

Et le soleil se levait sur nos fronts.

J’avais déjà vidé plus d’une bouteille,

Si bien qu’j’m’avais jamais trouvé si rond!

V’là la bourgeoise qui radine devant l’zinc:

“Feignant!”—qu’elle dit—“t’as donc lâché l’turbin?”

— “Oui,” que j’réponds, “car je vais au métingue,

Au grand métingue du Métropolitain!”

Verse 2

Les citoyens, dans un élan sublime,

Etaient venus, guidés par la raison;

A la porte, on donnait vingt-cinq centimes

Pour soutenir les grèves de Vierzon.

Bref, à part quatre municipaux qui chlinguent

Et trois sergots déguisés en pékins,

J’ai jamais vu de plus chouette métingue

Que le métingue du Métropolitain!

Verse 1

It was yesterday, Saturday, payday,

and the sun rose on our faces.

I’d already emptied more than one bottle,

so well that I’d never, indeed, found myself so drunk!

Suddenly, the missus turns up in front of the counter:

“Idler!” She says. “So, you’ve left work?”

“Yes,” I reply, “because I’m going to the meeting,

to the big meeting of the Métropolitain!”

Verse 2

The citizens, in a sublime enthusiasm,

had come, guided by reason;

at the door, you gave 25 centimes

to support the strikers of Vierzon.

Briefly, to the side were four stinking municipal guards

And three policemen disguised as civilians.

I’ve never seen a finer meeting

than the meeting of the Métropolitain!

42

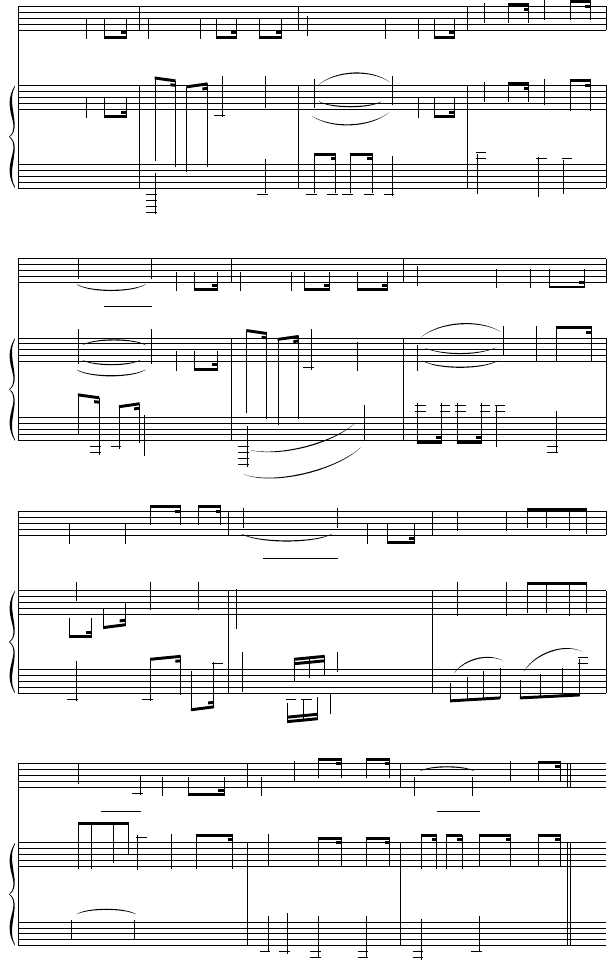

The well-crafted melody, the modulations in the harmony, and the

detail in the piano accompaniment reveal the skill of composer Camille

Baron, and place this chanson at the opposite pole musically from those

of Bruant; here, rather than a spontaneous quality suggesting the

street, the influences of the bourgeois salon are much in evidence—

though they feature in the context of parody (see ex. 8.5). The abruptly

juxtaposed loud and soft dynamics give the song an excitable, fidgety

character. The quiet beginning of the refrain suggests a conspiratorial

No Smoke without Water 207

208 Sounds of the Metropolis

Example 8.5 “Le Grand Métingue du Métropolitain” (1890), words by Mau-

rice Mac-Nab, music by Camille Baron.

&

&

?

#

#

#

c

c

c

Maestoso

R

œ

.

œ œ

C'é tait hi

R

œ

>

f

.

œ

>

œ

>

≈Œ

..

œ

R

œ

.

œ œ

.

œ

œ

er, sa me di, jour de

.

.

œ

œ

>

p

œ

œ

>

.

.

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

˙

˙

œ

œ

˙

J

œ≈

R

œ

.

œ œ

pa ye, Et le so

˙

˙

˙

j

œ

œ

œ

≈

R

œ

>

.

œ

>

œ

>

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

œ#

#‰Œ

œ

.

œ œ

œ

.

œ œ

leil se le vait sur nos

œ

.

œ œ

œ

œ

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

œ

œn

n

œ

œ

--- - -

&

&

?

#

#

#

5

˙

j

œ

≈

R

œ

.

œ œ

fronts. J'a vais dé

5

˙

˙

˙#

j

œ

œ

œ

≈

R

œ

.

œ œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

f

.

.

œ

œ#

#

>

œ

œ

>

J

œ

œ

>

‰Œ

..

œ

R

œ

.

œ œ

.

œ

œ

jà vi dé plus d'une bou

.

.

œ

œ

>

p

œ

œ

>

.

.

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

v

.

.

˙

˙

œ

œ

^

˙

J

œ

≈

R

œ

.

œ œ

teil le, Si bien qu'j'm'a

˙

˙

˙

j

œ

œ

≈

r

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

œ

œn

n œ

œ

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

J

œ

œ

‰

œ

œ

---

&

&

?

#

#

#

8

..

œ

R

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

vais ja mais trou vé si

8

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

>

.

œ

>

œ

>

˙

˙

.

.

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

>

.

.

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

>

˙

j

œ

≈

R

œ

.

œ œ

rond! V'là la bour

J

œ

œ

œ

‰≈

œ

œ

œ

j

œ

‰Œ

j

œ

œ

‰≈

œ

ƒ

m.d.

œ

œ

J

œ

‰Œ

.

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

geoise qui ra dine devant

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ#

doux

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

--

&

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

11

˙

j

œ

≈

R

œ

.

œ œ

l'zinc: «Feignant! – qu'elle

11

œ

œ

œ#

œ

œ

œ

g

g

g

œ

œ

œ

#

g

g

œ

œ

œ

g

g

J

œ

œ

œ

g

g

≈

r

œ

œ

œ

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙ œ

Œ

..

œ

r

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ#

œ

dit – t'as donc lâ ché l'tur

˙

˙

˙

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ

#

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œn

n

œ

œ#

#

œ

œn

n

˙

J

œ≈

r

œ#

p

.

œ œ

bin? – Oui, que j'ré

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ#

très doux

œ

œ

œ

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ

#

p

œ

œ

œ

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

--

hush. The knowing artifices of the song prevent it from having the kind

of authenticity effect that those of Bruant create. The ironic reception

called for in the text is also demanded by the music. In particular, the

overloud fanfares that punctuate phrases convey a satirical mood,

mocking the military use of such figures (reminding us that the blague

was a favorite fumist device). The unexpectedly delicate and graceful

codetta adds to the humor.

The satirical effect of fumisme can be gleaned from the following in-

cident. One evening, it is related, Mac-Nab was singing (with his voix de

fausset) a touching chanson about how a warm stove in a cold room

raises the spirits and encourages fond thoughts. He suddenly broke off

singing to recommend the purchase of a particular movable stove-on-

wheels (poêle mobile) costing 100 francs. His sales pitch was delivered

with the same intensity as his poetically expressed verse.

43

Thus the po-

etic appreciation of the stove was contrasted starkly with an apprecia-

No Smoke without Water 209

&

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

14

..

œ

r

œ

.

œ œ

.

œ

œ

ponds, car je vais au mé

14

œ

œ

œ

œ

g

g

g

g

>

p

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

g

g

g

g

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

.

j

œ

r

œ

.

œ œ

tin gue, Au grand mé

œ

œ

œ

œ

g

g

g

g

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

g

g

g

g

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

..

œ

r

œ

.

œ œ

.

œ

œ

tingue du Mé tro po li

œ

œ

œ

œ

g

g

g

g

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

g

g

g

g

>

.

.

.

.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

-- - ----

&

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

17

˙

j

œ

≈

R

œ

.

œ œ

tain!» – Oui, que j'ré

17

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

Ï

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

≈

œ

.

œ

.

œ

.

œ

>

œ

>

œ

>

œ

œ

Œ

3

..

œ

r

œ

.

œ

œ

.

œ

œ

ponds, car je vais au mé

œ

œ

œ

œn

g

g

g

cresc.

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

g

g

g

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

J

œ

≈

r

œ

p

.

œ œ

tingue Au grand mé

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

Ï

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

>

œ

œ

œ

œ

p

≈

œ

.

œ

.

œ

.

œ

>

œ

>

œ

>

œ

œ

Œ

3

-- -

&

&

?

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

#

20

œ

.

œ œ

œ

.

œ œ

tingue du Mé tro po li

20

œ

œ

œ

π

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

Ó

tain!»

˙

˙

˙

œ

p

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

˙

˙

&

∑

.

œ

J

œ

œ

j

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

œ

˙

˙

˙

∑

œ

ŒÓ

œ

ŒÓ

œ

-- --

tion of the stove as commodity. The crude juxtaposition of use value

and exchange value was something he returned to in his two volumes

of Poèmes mobiles.

The interests of the composer Paul Delmet (1862–1904) contrast

markedly with those of Mac-Nab. Pierre d’Anjou praises Delmet for his

charm, sentimentality, and tenderness.

44

He was not without his eccen-

tricities, however, such as taking out his glass eye and clinking it on his

glass to attract the attention of a waiter.

45

Moreover, his sentiment

could be ironic, as in his musical setting of “Les Petits Pavés,” written

by Maurice Vaucaire. Herbert suggests that Delmet’s music took such a

hold on the public that they forgot to pay attention to the words in a

song like this.

46

It becomes clear that the singer is a violent stalker.

Verse 1

Las de t’attendre dans la rue,

J’ai lancé deux petits pavés

Sur tes carreaux que j’ai crevés,

Mais tu ne m’es pas apparue.

Tu te moques de tout, je crois,

Tu te moques de tout, je crois;

Demain, je t’en lancerai trois!

Verse 3

Si tu ne changes pas d’allure,

J’écraserai tes yeux, ton front,

Entre deux pavés qui feront

A ton crâne quelques fêlures!

Je t’aime, t’aime bien, pourtant,

Je t’aime, t’aime bien, pourtant;

Mais tu m’en as fait tant et tant!

Verse 1

Tired of waiting for you in the street,

I threw two small paving stones

at your windows, which I smashed,

but you didn’t appear to me.

You make fun of everything, I believe,

You make fun of everything, I believe;

Tomorrow, I’ll throw three at you!

Verse 3

If you don’t change your style,

I’ll crush your eyes, your face,

between two paving stones,

which will make some cracks in your skull!

I love you, love you much, however,

I love you, love you much, however;

but you made me like this!

47

210 Sounds of the Metropolis

Delmet provided the music for poems by others. According to

Emile Goudeau, he was already composing a sentimental type of chan-

son in the Latin Quarter. Goudeau calls him the “musician of young

love,” and remarks that a distinctive feature of the Latin Quarter (not

shared by Montmartre) was its focus on youth. Goudeau specifies

twenty years old as the perfect age for enjoying that locality.

48

Yvette Guilbert (1867–1944) did not perform at the Chat Noir,

49

but she was recognized as having been influenced by it. An article in

the Echo de Paris claimed, “Montmartre . . . has made her what she is,

cadaverous and intensely modern, with a sort of bitter and deadly

modernity which she must have acquired at the Chat Noir.”

50

She

adopted a pale, unfashionably thin look for that time. She had endured

poverty when young, helping her seamstress mother, and was respon-

sive to the chansons réalistes of Bruant; “A la Villette” was in her reper-

toire. “La Soûlarde” (music by Eugène Poncin, 1884) was perhaps the

most famous of her Jouy songs. Like all her chansons modernes, she sang

it with her red hair worn up, wearing a simple green satin evening

dress and long black gloves (well known from Toulouse-Lautrec’s

posters), and she was felt to convey more of a sense of realism than

more elaborately costumed performers. As a diseuse, she gave primary

attention to enunciating words expressively.

51

An admirer wrote of her

“grace anémiée et maléfique” in this song.

52

She made a big impact

No Smoke without Water 211

Figure 8.2

Yvette Guilbert.