Scott Derek B. Sounds of the Metropolis: The 19th Century Popular Music Revolution in London, New York, Paris and Vienna

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

with it in London: Harold Simpson comments that it revealed “some-

thing new and hitherto undreamt of in the power of song as a medium

of dramatic expression.”

53

It concerns a drunken, wretched old woman

dragging herself down a street, enduring jeers and abuse. It avoids sen-

timentality, though it includes a plea for pity, and was probably found

morally acceptable as a warning of the degrading effects of alcohol.

Her repertoire was far from being unremittingly grim, and she re-

placed Thérésa as Paris’s star singer-comedian (and, like Thérésa, re-

turned with different and more “refined” repertoire in later life). When

performing at the café-concert, the scene of Thérésa’s greatest triumphs,

Guilbert had to find a middle course for her chansons modernes. Henry

Bauer, in the Echo de Paris, December 1891, writes:

Between the songs of inane depravity, which reigns supreme in the Café

Concert, and the artistic picturesque and powerful verses of Jules Jouy and

Bruant, there is now a middle kind . . . songs of delicate fancy, pointed

without being ill-natured, and not broad enough to be unpleasant. This

class of song has its own particular bard, whose name is Fourneau, or in

Latin Fornax, whence by anagram, Xanrof . . . On the scenario of these

songs, and others like them, Mdlle. Guilbert has built up by her own indi-

vidual genius the fabric of her art.

54

She represented bourgeois vices humorously in chansons like “Le

Fiacre” (Xanrof, 1888) and “Je suis pocharde!” (Laroche/Byrec, 1890).

When she sang at the respectable Eden-Concert in 1890, she was al-

lowed to sing the latter (concerning the effects of alcohol) but not the

former (concerning marital infidelity). As mentioned in chapter 3, it

was Guilbert’s introduction to “Je suis pocharde!” that helped to win it

acceptability, since she took care to provide a narrative frame concern-

ing a respectable girl who had become slightly tipsy (gentiment grise)

drinking champagne at her sister’s wedding.

55

“Pocharde,” especially in

this its feminine form, would have registered disapproval and pity,

whereas “gentiment grise” is a benevolent expression. Besides, it has a

forerunner in “Griserie,” the eponymous character’s tipsy song in Of-

fenbach’s La Périchole (1868). Having taken all that into account, how-

ever, Guilbert was particularly skilled at innuendo.

56

What she did not

possess was the political awareness of Eugénie Buffet (1866–1934),

who was also singing the chansons réalistes of Bruant and others in the

1890s, one such being Jouy’s “La Terre” (a chanson dedicated to Emile

Zola). Buffet had been sentenced to fifteen days in prison for shouting

“Vive Boulanger!” (the discredited general) in 1889, and this experi-

ence had given her the idea for her stage persona of the pierreuse or

low-class prostitute. She sang politically engaged songs, perhaps her

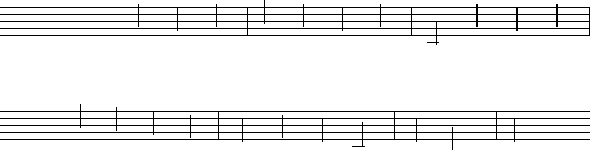

best known being “Pauvre Pierreuse!” (1893) (ex. 8.6). Her success en-

abled her to run her own cabaret, La Purée, at 75, boulevard de Clichy.

Although a new market had developed for these cultural goods,

212 Sounds of the Metropolis

certain classes and class fractions could only acquire the new goods if

they were made available in a socially suitable market. In Paris, the

Mirliton was not a suitable venue for some. Though Bruant obtained

permission to open till 2:00 a.m. (establishments with music normally

had to close at midnight) and held a jour chic with higher prices on Fri-

days (as Salis had done), he attracted only a higher-class bohemian

crowd who went there after the theatre. Yvette Guilbert says it was a

revelation for the audience at the Divan Japonais, 75, rue des Martyrs,

when she began singing chansons by Bruant there in 1891; for the first

time these songs had left their home ground and, through her, were to

become popularized.

57

Perhaps she was persuaded she might use Bru-

ant’s material by the way Bruant himself was prepared to sing from a

female perspective in chansons like “A la Villette,” “A la Grenelle,” and

“A Saint-Lazare.” Bruant actually encouraged Guilbert to sing his chan-

sons, saying, “tu as ton talent et ton coeur qui saigne.”

58

She made her

reputation and developed her characteristic repertoire at the Divan

Japonais. Like the Chat Noir, it had a jour chic on Fridays, when a more

upmarket audience would attend.

Next, it was the haute bourgeoisie who wished to hear her, but who

felt uncomfortable frequenting the café-concert. Therefore, arrange-

ments were made for her to appear at the Théâtre d’Application, rue

Saint-Lazare. The proprietor begged the many women in the audience

not to be shocked

59

—although that is probably the reason they had

turned up. She successfully “crossed over” and, by the mid-1890s, had

admirers in all classes. After her appearance at London’s Empire in

1894, a press reception was held at the luxurious Savoy Hotel, and she

was soon being welcomed in fashionable society. On her second visit to

London, in 1896, she was invited to dine with the Prince of Wales. She

was at that time performing at the Duke of York’s Theatre with the re-

spectable British music hall entertainer Albert Chevalier, whom she

later joined for a combined tour of the United States. Her repertoire had

now mellowed even further, and she and Chevalier made an appropri-

ate coupling.

No Smoke without Water 213

Example 8.6 “Pauvre Pierreuse!” (1893), words by Paul Rosario, music by

G. Marrietti.

&

b

b

b

4

2

‰

j

œ

j

œ#

j

œ

A vez vous,

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ#

j

œ

le soir, par ha

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ#

j

œ

sard, Ren con tré----

&

b

b

b

j

œ

j

œ

j

œn

j

œ

sur le bou le

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ

j

œ#

vard U ne ro

œ

œ

deu

.

œ

se-- - - -

The Proliferation of Artistic Cabarets

It would be pointless to produce a telephone directory–style list of all

the important artistic cafés and cabarets around Montmartre.

60

Some of

the most important, not so far mentioned, were the gothic Abbaye de

Thélème (1, place Pigalle) and the rustic Auberge du Clou (30, avenue

Trudaine, next to the Grande Pinte). The Rat Mort (Dead rat), place Pi-

galle, catered to a double clientele, as did many others: Goudeau men-

tions anarchists and authoritarians, writers and businessmen existing

side by side.

61

Alphonse Allais thought the beer there terrible, and was

not averse to smuggling in a bock purchased from the Nouvelles Ath-

ènes across the street.

62

On the boulevard de Clichy were the twin ca-

barets Le Ciel et L’Enfer (Heaven and Hell), with the waiters dressed as

angels in the one and as skeletons in the other. Also on the same boule-

vard, at number 62, was the long-lived Quat’z’Arts cabaret (1893–

1924), which featured poets and chansonniers of Montmartre and be-

came the preeminent cabaret artistique after the Chat Noir closed in

1897.

63

It contained a gothic café room, a restaurant, and a theatre at

the rear with around 150 seats. It was the first cabaret to put on a revue

(in 1894) and had a journal edited by Goudeau from 1897. Jarry’s Ubu

Roi, though first performed in 1896, was given for the first time with

puppets, as he preferred, at the Quat’z’Arts in 1901 (running for sixty-

four performances). However, this should not be taken as an indication

that the Quat’z’Arts was committed to provoking the bourgeoisie: the

popular Anglo-French entertainer Harry Fragson also had his début

there. The artistic cabarets of Montmartre were relying on wealthy

middle-class patronage before the century was out and, as Goudeau

commented, “saw at their formerly modest doors the throng of embla-

zoned carriages and the wealthiest bankers contributing their subsidy

to this former Golgotha transformed into Gotha of the silly songs.”

64

By

then, Bruant had himself retired to a country estate.

65

Maurice Boukay, looking back on the final years of the Chat Noir

just after it had closed, wondered what had really been achieved. He

describes the legacy of artistic cabarets as the tail of the Chat, but notes

that the cat’s tail is very long, and suspects it has been pulled too far. He

expresses his irritation at the number of imitators of Bruant and Guil-

bert, and declares his weariness of scatology, the macabre, and ugli-

ness. He recounts his attempt, with Delmet, to renew the love song

without all the “sickening banalities” heard in low-class entertainment

venues (bastringues). He remarks despondently that he and his friends

did not succeed in chasing away the inanity or pornography of the café-

concert.

66

Yet some things of enduring value had undoubtedly been

achieved: Carco, for example, praises Bruant for creating the folklore of

the outlying quarters of Paris.

67

Lest the artistic freedom of the cabarets be exaggerated, it is impor-

tant to remember that they were always under the necessity of being

214 Sounds of the Metropolis

alert to the perils of censorship and closure. The Chat Noir was an ex-

ception, since it was the first cabaret of its kind, and thus its official au-

thorization was retrospective. Moreover, because it was made up of

“poètes et de chansonniers dont les œuvres avaient une valeur artis-

tique,” it avoided the normal censorship process (that is, having to sub-

mit its programs in advance to the censor).

68

Bruant’s Mirliton inher-

ited the same concession, since it occupied the same premises as the

original Chat Noir. All other cabarets, however, were opened only after

official authorization and were, therefore, subject to normal censor-

ship. In 1895, the year Bruant retired, the chansonnier Joanot waved

a red flag at the Cabaret du Coup de Gueule (108, boulevard Roche-

chouart), claiming that he was demonstrating how railway workers

controlled carriages. The Préfecture de Police closed the establishment

down for having permitted the exhibition of a seditious emblem.

69

Steven Whiting sourly sums up the cabarets artistiques as designed

to package bohemian Montmartre for Parisian consumption, suggest-

ing that, instead of being artistic haunts that the bourgeoisie gate-

crashed, they from the beginning “made wry obeisance to art, to youth,

to social concern, and to a romanticized past, all the while exploiting

their profit-making potential.”

70

I think he overplays the manipulative

character of the cabarets; the Hydropathes, for example, met to pursue

their artistic interests, not to make money, and they did not change

overnight when they decamped to the Chat Noir. Boukay points to the

rejection of the “muse of Montmartre” by legitimating institutions:

“L’Académie nous fait la moue” (the Academy pulls its face at us).

71

Moreover, Salis did not pay chansonniers to perform until forced to by

competition from elsewhere; therefore, they had no incentive, at first,

to appeal to the bourgeoisie. Certainly, things had changed at the end

of the century. Théodore Botrel, for example, whose début was at the

Chien Noir and whose social conscience is evident in his earlier chan-

sons like “Le Couteau,” moved politically to the right and even pro-

duced chansons royalistes. Yet this should not cloud our judgment about

the original motivations of Montmartre cabaret, nor should the fact

that many of the newer cabarets opened with only commercial aims.

72

Lisa Appignanesi has argued that the Chat Noir artists “identified with

the people in their immediate Montmartre environment”;

73

and Ar-

mond Fields supports this “artist in the community” view: “The artists

and writers who frequented the cabaret and contributed to its opera-

tion were themselves mostly residents of Montmartre. They repre-

sented the locals.”

74

Bruant himself lived in Montmartre, in the rue des

Saules at the corner of rue Cortot.

75

Nevertheless, the cabarets partici-

pated in a professional art world rather than a folk tradition. In her

preface to Emile Bessière’s Autour de la Butte: Chansons de Montmartre et

d’ailleurs (1899), Yvette Guilbert speaks of the international success of

Bessière’s “Au Clair de la lune” in Paris, London, and America, and ex-

plains that this is because the words are tender, human, and may be

No Smoke without Water 215

understood by all.

76

What makes these chansons different from those

of the café-concert, however, is their ability to turn at any moment

from broad and inoffensive lyrics to the harshest social realism, as Bes-

sière exemplifies in “Les Morphinomanes,” perhaps the first song about

drug addiction:

A la morphine chaque jour,

Elles se piqu’nt avec amour

Chacqu’ parti’ du corps tour à tour,

En vicieuses courtisanes.

77

Every day they prick

lovingly with morphine

each part of the body in turn,

like lecherous courtesans.

Cabaret and the Avant-Garde

The artistic cabarets of Montmartre—of which only the Lapin Agile of

1903 survives (2, rue des Saules)

78

—raise important questions about

the relationship between avant-gardism, modernism, and popular cul-

ture that have particular relevance today. Fields has claimed the Chat

Noir characterized the “heart and spirit” of the Parisian avant-garde of

that time.

79

It is obvious that something unique was happening in the

arts in Montmartre in the 1880s, and equally obvious that it involved

a mixing of high and popular culture. A typical reading of the events in

Montmartre sees them as paving the way for modernism; but it can also

be argued that a new kind of popular culture was created there with

the birth of poster art and a new type of cabaret that soon spread

throughout Europe (among the first successors being the Quatre Gats,

Barcelona; the Elf Scharfrichter, Munich; Schall und Rauch, Berlin;

and Die Fledermaus, Vienna).

80

The influence of Montmartre lived on

longer than that, and not just in France; in Britain and United States,

Tom Robinson, Jake Thackray, Scott Walker, and Leon Rosselson are all

names that spring to mind.

Henri de Saint-Simon, the first to apply the military term “avant-

garde” to art,

81

believed that art could and should play an active role in

the struggle for a freer and fairer society. The morale of the Saint-Simo-

nians and Fourierists (who also adopted this term) was sapped by the

failure of 1848, the coup d’état of 1851, and the establishment of the

Second Empire. The avant-garde artists of the 1860s maintained a con-

cern with contemporary Parisian life, but put most of their energy into

challenging the official art of the Académie. When a Prussian victory

ended the Second Empire in 1871, huge war reparations followed and

caused an economic depression. The meaning of “avant-garde” grew

vaguer from then on and, in the 1880s, began to refer to art that had

no explicit connection to politics, such as impressionism—an early ex-

216 Sounds of the Metropolis

ample of turning a “revolt into a style.”

82

An avant-gardist was now

someone interested primarily in aesthetic progress (attacking “official”

art) rather than social progress, and that is how the avant-garde be-

came linked to modernism in the arts. Aesthetic rebels, like those of the

Salon des Indépendants, replaced political rebels. In the twentieth cen-

tury, however, avant-garde formations in western Europe seemed to be

competing against each other in the absence of an official art to attack.

Whereas nineteenth-century avant-gardism had a social impetus, the

twentieth century variety had an aesthetic impetus: art as a vehicle for

experimentation in style and structure; art as artistic problem solving;

art as radical departure from existing art; art as challenge to artistic con-

vention; art that moves away from subjects to abstract ideas; and art that

makes its own materials explicit. The Montmartre artists often champi-

oned the popular against the high, but for a mid-twentieth-century

critic like Clement Greenberg, avant-gardism was at the opposite pole

to Kitsch and was driven by a search for the autonomous artwork.

83

The

move to detach art from society and dissolve content into form is what

other theorists have regarded as the hallmark of modernism. Adorno,

in his Aesthetic Theory, follows a line not dissimilar to Greenberg: the

avant-garde is either conflated with modernism or rejected for merely

fetishizing the new.

84

Another writer who conflates avant-gardism and

modernism is Bernard Gendron.

85

It is to be wondered if there is not

room for a separate theory of the avant-garde. Dada does not seem to fit

Greenberg’s theory. Tristan Tzara’s Dada Manifesto (1918) condemned

“laboratories of formal ideas” and proposed that there was “a great neg-

ative work of destruction to be accomplished.”

86

Peter Bürger, in his Theory of the Avant-Garde, sees the avant-garde

arising as a response to aestheticism in bourgeois society, where art is

“no longer tied to the praxis of life” and has become socially function-

less.

87

For Bürger, avant-gardists, though they do not restore the social

function of art, do negate the autonomy of art, as, for example, when

Duchamp exhibited a mass-produced urinal, entitled it Fountain, and

signed it R. Mutt (a sanitary engineer). The artists of the Chat Noir and

the Quat’z’Arts liked to confuse fake and real, and often concealed iden-

tities with nicknames or pseudonyms. An important feature of avant-

gardism, for Bürger, is its rejection of an artistic tradition; thus, Dada fits

well into his conception, while cubism (which was no problem for

Greenberg) is more awkward for him to accommodate. Nevertheless,

the Montmartre artists did not so much break with tradition as create

new fusions of high and low art. Well-known musical examples would

be Satie’s Gymnopédies and Gnossiennes. The chansons of Bruant, Jouy,

and Mac-Nab were at home neither in concert hall nor café-concert

(though, as mentioned earlier, Bruant was persuaded to appear at the

Ambassadeurs in 1992, on condition that the stage set reproduced the

interior of his own cabaret).

The Montmartre avant-gardists fit better into the postmodern the-

No Smoke without Water 217

orizing of Andreas Huyssen, who suggests that avant-gardists are those

that have challenged the “great divide” between modernism and “com-

mercial mass culture.” The Montmartre chansonniers, of course, fre-

quently drew on popular forms, or raised the status of the “trivial” as a

means of critiquing the artistic values of their society. Carco calls Bru-

ant “un grand poète populaire”;

88

and Bruant’s work certainly asserts

the category of the demotic in both vocabulary and technique (he

avoids, for example, high-art Alexandrines in his verse). Huyssen holds

that “the historical avant-garde aimed at developing an alternative re-

lationship between high art and mass culture and thus should be dis-

tinguished from modernism, which for the most part insisted on the in-

herent hostility between high and low.”

89

At the same time, he accepts

that the boundaries between avant-gardism and modernism were

fluid. I have to say I do not like the term “mass culture,” which imme-

diately suggests a now discredited theoretical paradigm in which there

are manipulative producers and passive consumers; however, reworked

as “popular culture,” I can accept much of Huyssen’s argument. Yet I

want to go further. Huyssen, like Bürger, sees avant-gardism springing

out of “high culture”; I would like to broaden the perspective and con-

sider the implications of viewing certain developments in the popular

arena as avant-garde. For example, what would it mean to regard Pink

Floyd, the Doors, and Frank Zappa as avant-garde, or the Beatles in

their albums Revolver and Sgt. Pepper?

90

The mood of the boulevard de

Rochechouart in the 1880s may have been not unlike that of Carnaby

Street, London, in the 1960s. Perhaps Bob Dylan might be seen as the

Aristide Bruant of the 1960s: think of his creation of a provocative new

rock and folk hybrid style coupled to lyrics of social concern, as heard,

for example, in “Desolation Row.” Perhaps, when we give the label

“counterculture” to events in the 1960s, we are really referring to an

avant-garde culture in the older sense of that term.

218 Sounds of the Metropolis

Notes

219

Introduction

1. Music and Society since 1815 (London: Barrie and Jenkins, 1976), 147.

Adorno mentions the “scars of capitalism” that afflict all forms of twentieth-

century art in a letter to Walter Benjamin, 18 Mar. 1936, in Theodor W. Adorno:

Über Walter Benjamin, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1970),

126–34.

2. See Howard Becker, Art Worlds (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1982), 35, 78. Becker accepts that a number of specific art worlds may share

certain activities and features that allow them to be considered as part of a more

general art world (161).

3. Art Worlds, 305, 307. Becker’s arguments then begin to depart from my

own, because he concentrates on revolutions in an art world that lead to new

accepted practices, whereas I am interested in revolutions that leave a state of

continuing struggle. For example, the added sixth continues throughout the

nineteenth century to be rejected in the musical high-art world as a vulgarism.

I conceive of the practices I’m discussing as revolutions that lead to new art

worlds. Becker sees a revolution as something that causes changes in an exist-

ing art world, while he understands new art worlds as those that bring together

“people who never cooperated before” and “conventions previously unknown”

(310); he regards rock music, for example, as a new art world (313).

4. Theodor W. Adorno, Introduction to the Sociology of Music, trans. E. B. Ash-

ton (New York: Continuum, 1989; originally published as Einleitung in die

Musiksoziologie [Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1962]).

5. “Nicht bloss werden die Ohren der Bevölkerung so mit leichter Musik

überflutet, dass die andere sie nur noch als der geronnene Gegensatz zu jener,

als ‘klassisch’ erreicht.” Philosophie der neuen Musik (Frankfurt: Europäische Ver-

laganstalt, 1958), 17.

6. “Die Unterschiede in der Rezeption der offiziellen ‘klassischen’ und der

leichten Musik haben keine reale Bedeutung mehr.” Dissonanzen. Musik in der

verwalteten Welt (1956), in Gesammelte Schriften (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag,

1973), 14:21.

7. Philosophy of Modern Music, trans. Anne G. Mitchell and Wesley V. Blom-

ster (New York: Seabury Press, 1973), 8. Adorno actually wrote “von Gebrauch

ganz sich losgesagt” (quite renounced use), 15.

8. Michel Foucault and Pierre Boulez, “Contemporary Music and the Pub-

lic,” trans. John Rahn, Perspectives of New Music (fall–winter 1985), 6–12; see 8

and 11, excerpted as “On Music and Its Reception,” in Derek B. Scott, ed.,

Music, Culture, and Society: A Reader (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000),

164–67; see 165 and 167.

9. Carl Dahlhaus, Esthetics of Music, trans. William Austin (Cambridge: Cam-

bridge University Press, 1982; originally published as Musikästhetik [Cologne,

1967]), 96.

10. Henry Lunn, in 1866, refers to the worship of the “popular idol” in

“The London Musical Season,” Musical Times and Singing Class Circular 12, no.

283, 1 Sep. 1866, 363–65, 363. Even those twentieth-century pop idols who

rose to fame on their “street credibility” but then developed aristocratic aspira-

tions merely replicate the behavior of nineteenth-century stars like cabaret

performer Aristide Bruant, who bought himself an estate and ended his life as

a respectable châtelain.

11. A seminal study of class and music in three of the cities I am dealing

with—London, Paris, and Vienna—is William Weber, Music and the Middle Class:

The Social Structure of Concert Life in London, Paris and Vienna between 1830 and

1848, 2nd ed. (Aldershot, England: Ashgate, 2003; originally published Lon-

don: Croom Helm, 1975), but it focuses on the earlier part of the nineteenth

century (1830–48). Weber is currently working on a book with further paral-

lels to my own work, entitled The Great Transformation. An important study of

antecedents of twentieth-century popular music is Peter Van der Merwe, Ori-

gins of the Popular Style (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), but it lacks the kind of

historical and cultural contextualization that characterizes my work and in-

stead spends much time tracing stylistic features from one piece to another in

a fairly traditional “genealogical” manner. Moreover, it does not identify or ex-

plain the significance of the four particular cities I have singled out to changes

in Western popular musical style. (The index has eight page references for Vi-

enna, four for New York, and none for London and Paris.)

12. See M. Maretzek, Revelations of an Opera Manager in Nineteenth-Century

America, pt. 1 (New York: Dover, 1968; originally published as Crotchets and Qua-

vers, [n.p.: 1855]), 25; see also Charles Hamm, Yesterdays: Popular Song in Amer-

ica (New York: Norton, 1979), 69. While accepting that many features of Amer-

ican society, such as fluidity of status, can be related to the absence of a feudal

era, C. Wright Mills complains that this has been confused with lack of class

structure and class consciousness; The Sociological Imagination (New York: Ox-

ford University Press, 1959), 157.

13. For instance, you will find no Offenbach, no Lanner or Strauss, and

definitely no London music hall or New York black musicals in Richard L.

220 Notes to Pages 6–8

Crocker’s compendious A History of Musical Style (New York: McGraw-Hill,

1966). The few French popular elements that are mentioned are only seen as

relevant in the context of the canonized work of Les Six and Stravinsky.

14. Oscar A. H. Schmitz, Das Land ohne Musik: Englische Gesellschaftsprob-

leme, 8th ed. (Munich: Georg Müller, 1920), 30.

15. David Ewen, American Popular Song (New York: Random House, 1966),

74.

16. From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, trans. and ed. by H. H. Gerth and

C. Wright Mills (New York: Oxford University Press, 1946), 185. Weber desig-

nates a “status situation” as “every typical component of the life fate of men that

is determined by a specific, positive or negative, social estimation of honor” (187).

This expresses itself in a specific lifestyle (for example, one that rejects the pre-

tensions brought about by riches). Nevertheless, “[t]he differences between

classes and status groups frequently overlap” (193). Weber’s arguments were put

forward in Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft [Economy and Society] (1922), pt. 3, chap. 4.

17. See Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste,

trans. R. Nice (London: Routledge, 1984; originally published as La Distinction.

Critique sociale du jugement [Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1979]), 14–18.

18. Music and the Middle Class, viii–xv, 8–10, and 140; and in “The Muddle

of the Middle Classes,” 19th Century Music 3 (1979), 175–85.

19. A class fraction is an identifiable grouping within a particular class

whose behavior or opinions may not be characteristic of the class as a whole

and who may even play an oppositional role at times; for example, middle-class

temperance campaigners who cut across the dominant middle-class view of a

free market. A class fraction should not be confused with a social stratum—for

example, bachelors under the age of forty.

20. “Popular Music,” in Stanley Sadie, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of

Music and Musicians, 2nd ed., 29 vols. (London: Macmillan, 2001), 20:128–30.

21. See Derek B. Scott, From the Erotic to the Demonic: On Critical Musicology

(New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), 38. Weber discusses his idea that

there existed a “general” taste for popular music in the first half of the nine-

teenth century in Music and the Middle Class, xxiii. However, the term “general”

suggests a taste consensus achieved without struggle, without contest over

meanings.

22. Van Akin Burd, ed., The Winnington Letters (London: Allen and Unwin,

1969), 528–29, cited in Sara M. Dodd, “Ruskin and Women’s Education,” paper

presented at the Association of Art Historians conference, Sheffield, Apr. 1988.

23. See Carl Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music, trans. J. B. Robinson

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 110–11.

24. See Dave Harker, Fakesong: The Manufacture of British “Folksong” 1700 to

the Present Day (Milton Keynes, England: Open University Press, 1985), 155–56.

25. Raynor, Music and Society since 1815, 132.

26. Discussion of both, as well as of productive forces (mentioned in the

next sentence), is in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Die deutsche Ideologie

(1846), full text based on the original manuscript in Marx-Engels-Lenin Insti-

tute, Moscow, www.mlwerke.de/me/me03/me03_009.htm. Class and class

struggle is featured in Marx’s English journalism, for example, “The Chartists,”

New York Daily Tribune, 25 Aug. 1852, in T. B. Bottomore and M. Rubel, eds.,

Karl Marx: Selected Writings in Sociology and Social Philosophy, 2nd ed. (Har-

mondsworth, England: Penguin, 1961), 204–7.

Notes to Pages 8–11 221