Schenken Suzanne O’Dea. From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics (2 Volumes)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

families. With discrimination against women in tax laws her greatest con-

cern, she sought to eliminate the inheritance tax for surviving spouses and

to end the inequities of the marriage tax, under which married couples

paid higher income taxes than two single people with the same income.

A strong supporter of equality for women and men, she began intro-

ducing equal pay bills in the 1950s and helped pass the Equal Pay Act of

1963. When Congress considered the 1964 Civil Rights Act, primarily in-

tended to address race issues, Griffiths believed that if Title VII of the act,

prohibiting discrimination in employment, did not include sex as a pro-

tected category, then white women would be left without protection. She

considered offering an amendment to add sex but encountered opposi-

tion from the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Or-

ganizations (AFL-CIO), Assistant Secretary of Labor Esther Peterson, and

others who feared that adding sex would threaten passage of the whole

act. Then, she explained: “I made up my mind that all women were going

to take one giant step forward, so I prepared an amendment that added

‘sex’ to the bill.” When she learned that conservative congressman Howard

W. Smith of Virginia intended to offer the amendment, she applauded his

decision, believing that under his sponsorship the amendment would at-

tract at least 100 votes that it would not under her sponsorship. She

turned her attention to finding the rest of the needed votes.

House debate on the amendment quickly turned into a farce. Smith

said that he offered it to correct the “imbalance of spinsters,” and another

congressman called the amendment “illogical, ill timed, ill placed, and im-

proper.” As her colleagues laughed at the amendment, Griffiths entered

the debate, reviewed relevant court cases, and said: “A vote against this

amendment today by a white man is a vote against his wife, or his widow,

or his daughter, or his sister.” The amendment passed 168 to 133. She con-

tinued to work for the bill’s passage in the Senate, where it passed.

The act included the creation of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission (EEOC) to enforce the provisions. The EEOC’s executive di-

rector, however, felt that the commission’s focus should be on race and

dismissed the prohibition against sex discrimination in employment, call-

ing it “a fluke . . . conceived out of wedlock.” Although sex discrimination

complaints accumulated, the EEOC mocked the provision. In 1966, Grif-

fiths attacked the commission’s disregard for complying with its mandate,

asking: “What is this sickness that causes an official to ridicule the law he

swore to uphold and enforce?...What kind of mentality is it that can ig-

nore the fact that women’s wages are much less than men’s, and that Ne-

gro women’s wages are least of all?”

The other outstanding example of her leadership was the Equal

Rights Amendment, first introduced in Congress in 1923. For more than

Griffiths, Martha Edna Wright 305

twenty years, it had been locked in the Judiciary Committee by Represen-

tative Emanuel Celler, until Griffiths gathered the 218 signatures from her

congressional colleagues to bring it to the House floor for debate. On 10

August 1970, the House passed the amendment, 352 to 15, with seventy-

four members not voting, but the Senate did not approve it. Griffiths in-

troduced the amendment again in 1971, making two compromises: a

seven-year limit on the ratification period and a two-year delay in imple-

menting it following ratification. In 1972, Congress approved the amend-

ment and sent it to the states for ratification, but it failed in the states.

Griffiths decided against running in 1974. She returned to politics in

1982, when she won the race for Michigan’s lieutenant governor, serving

from 1983 to 1991.

See also Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII; Congress, Women in; Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission; Equal Pay Act of 1963; Equal Rights

Amendment; Peterson, Esther; Smith, Howard Worth; State Legislatures,

Women in

References George, Martha W. Griffiths (1982); Kaptur, Women in Congress

(1996); Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives, Women in

Congress, 1917–1990 (1991).

Grimké, Angelina Emily (1805–1879)

and Sarah Moore (1792–1873)

The daughters of slaveowners in the South and the only white southern

women leaders in the abolitionist movement, Angelina and Sarah Grimké

worked to end slavery. As agents of the American Anti-Slavery Society, the

sisters described the horrors of slavery to New England audiences and

helped found female antislavery societies.

Born in Charleston, South Carolina, the Grimké sisters were edu-

cated at home and in private schools to become members of Charleston’s

society. Sarah Grimké was particularly resentful that her brothers had re-

ceived a good advanced education, an opportunity denied to her.

In 1819, Sarah Grimké met a prominent Quaker with whom she had

extensive conversations during a sea voyage from Philadelphia to

Charleston. When she returned home, she continued to study Quakerism.

Sarah reported that she heard voices that told her to return to Philadel-

phia, which she did in 1821, the year she became a Quaker. Angelina

joined her sister in Philadelphia in 1828 and also became a Quaker.

By 1836, the sisters had become committed to the abolitionist move-

ment. That year, Angelina Grimké wrote Appeal to the Christian Women of

the South and Sarah Grimké wrote An Epistle to the Clergy of the Southern

States, published by the American Anti-Slavery Society. The works were

significant for their condemnation of slavery by women who had been

306 Grimké, Angelina Emily and Sarah Moore

part of a slave society. The next year, the women were leaders in a women’s

antislavery convention that has been described as the “first major organi-

zational effort of American women.”

As the first female agents of the American Anti-Slavery Society, the

Grimké sisters went on several speaking tours between 1837 and 1839.

These lectures were among the greater of their contributions to the aboli-

tionist movement, and their public speeches placed them among the pio-

neers of the women’s rights movement. The speeches, however, proved

controversial because of social mores that questioned the appropriateness

of women speaking in public and because they spoke to audiences of

women and men. Of the controversies, Angelina wrote: “We Abolition

Women are turning the world upside down.” In 1837, the Ministerial As-

sociation of the Congregational Churches of Massachusetts issued a pub-

lic “Pastoral Letter” that was clearly directed at Angelina Grimké, con-

demning her for speaking before audiences of women and men. In

addition, the press attacked her for the same reasons.

The Grimké sisters believed that women and men were equal as

moral beings, had equal moral duties as children of God, and had an equal

right to fulfill them. In their belief system, if an act was morally right for

a man to do, it was also morally right for a woman. Angelina Grimké de-

veloped her argument for women’s rights from her understanding of her

biblical duty to take action in moral areas, which led her to an insistence

that women had a right to a voice in all the laws under which they lived

and that women had a right to sit in Congress or be president.

In her feminist writings, Sarah Grimké argued that parallels existed

between slavery and women’s status, explaining that in both situations,

one group exerted power over another group—whites over slaves and

men over women—and that when power is used in such a way, one group

benefits and the other group is exploited. She said that women “ought to

feel a peculiar sympathy in the colored man’s wrong, for like him, she has

been accused of mental inferiority, and denied the privileges of a liberal

education.” Sarah Grimké believed that men had usurped women’s power

and that women had accepted the concept of men’s superiority. She wrote:

“I ask no favors for my sex. All I ask of our brethren is, that they take their

feet from off our necks, and permit us to stand upright on that ground

which God designed us to occupy.” Her development of these concepts

made her a major feminist theorist and pioneer, but they aroused opposi-

tion to the Grimké sisters both inside and outside the abolitionist move-

ment. Some thought that adding women’s issues to the debate would in-

crease opposition to the abolitionist movement.

In 1838, Angelina Grimké married Theodore Weld, one of the lead-

ing abolitionists of the time. The two sisters and Weld wrote American

Grimké, Angelina Emily and Sarah Moore 307

Slavery as It Is: Testimony of a Thousand Witnesses (1839), considered the

most important antislavery document written before Harriet Beecher

Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. They continued to do research, assist local

African Americans, and work for women’s rights, but their period of in-

tense activity ended in 1839.

See also Abolitionist Movement, Women in the; Public Speaking; Stowe, Har-

riet Elizabeth Beecher

References Lerner, The Feminist Thought of Sarah Grimké (1998); Matthews,

Women’s Struggle for Equality: The First Phase, 1828–1876 (1997).

Griswold v. Connecticut (1965)

In its 1965 decision in Griswold v. Connecticut, the U.S. Supreme Court

expanded the concept of the right to privacy that had been articulated in

other cases, but from different perspectives. In its decision the Court over-

turned a Connecticut law that prohibited the dissemination and use of

contraceptive devices and drugs.

Planned Parenthood had twice tried to take a case to court to over-

turn the law, but on both occasions, the court invoked procedural grounds

to avoid making a decision. In 1961, executive director of the Planned Par-

enthood League of Connecticut Estelle Griswold and Yale Medical

School’s department of gynecology and obstetrics professor C. Lee Bux-

ton had established a birth control clinic in New Haven, Connecticut, to

provoke another test case. Griswold and Buxton were arrested and con-

victed of giving birth control information to married women and were

fined $100 each.

The Court resisted deciding the case on the basis of the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, choosing instead to explain that

within the rights articulated in the Constitution reside peripheral rights

without which “the specific rights would be less secure.” Noting that “the

First Amendment has a penumbra where privacy is protected from gov-

ernmental intrusion,” the Court also found a variety of guarantees creat-

ing zones of privacy in the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments. Based

upon this reasoning, the Court wrote:

The present case, then, concerns a relationship lying within the

zone of privacy created by several fundamental constitutional

guarantees. And it concerns a law which, in forbidding the use

ofcontraceptives...seeks to achieve its goals by means having

a maximum destructive impact upon that [marital] relation-

ship.... Would we allow the police to search the sacred

precincts of marital bedrooms for telltale signs of the use of

contraceptives? The very idea is repulsive to the notions of pri-

vacy surrounding the marriage relationship.

308 Griswold v. Connecticut

In 1973, the right of privacy identified in Griswold v. Connecticut be-

came fundamental to the Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, which ruled that

laws prohibiting abortions were unconstitutional.

See also Abortion; Fourteenth Amendment; Roe v. Wade

References Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965).

Grove City College v. Bell (1984)

In Grove City College v. Bell, the U.S. Department of Education sought to

enforce its understanding of Title IX of the Education Amendments of

1972, which prohibits sex discrimination in “any education program or

activity receiving federal assistance.” The Department of Education un-

derstood that to mean that if any program or person received federal

funds, the whole institution had to file an assurance of compliance report.

Grove City College refused, arguing that it did not directly receive federal

funds. The Department of Education replied that because students at-

tending the college received Basic Educational Opportunity Grants, the

college’s compliance was necessary for the students to continue receiving

the financial assistance.

The U.S. Supreme Court decided that the Department of Education

could terminate students’ grants, that doing so would not be an infringe-

ment of their rights, and that institution-wide coverage under Title IX was

not required because some students received financial assistance. The de-

cision limited the Department of Education’s authority to investigate dis-

crimination complaints, especially in women’s athletics. The decision out-

raged some feminists and women members of Congress, who believed

that if any federal funds went to an educational institution, even if it were

direct assistance to a student, the whole institution had to comply with Ti-

tle IX. Congress passed the Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1988 to over-

turn the decision.

See also Civil Rights Restoration Act of 1988; Education Amendments of 1972,

Title IX

References Grove City College v. Bell, 465 U.S. 555 (1984).

Guinier, Lani (b. 1950)

African American lawyer Lani Guinier’s nomination to head the civil

rights commission of the U.S. Department of Justice in 1993 evoked

strong protests from congressional conservatives who accused her of hav-

ing dangerously radical views on minority rights. The concepts under at-

tack included a wide range of ways to enhance minority power, such as

cumulative voting in elections, which permits voters to concentrate on

selected candidates. In legislative bodies, Guinier proposed requiring

Guinier, Lani 309

supermajorities on some votes and permitting minorities veto power on

some issues. U.S. senator Orrin Hatch called her ideas “frightening,” and

U.S. senator Bob Dole said: “The key concept has always been access, not

proportionality.”

Guinier appeared on television news programs to explain her ideas,

and her supporters claimed that her views had been distorted, but the at-

tempts to save her nomination failed. President Bill Clinton withdrew

Guinier’s nomination without permitting her to defend her ideas before

the Senate Judiciary Committee, angering members of the Congressional

Black Caucus, who viewed the withdrawal as evidence of weak leadership

by Clinton.

Born in New York City, Guinier graduated from Radcliffe College in

1971 and received her law degree from Yale Law School in 1975. While in

law school, she met Hillary Rodham Clinton and Bill Clinton. In the late

1970s, Guinier worked for the civil rights division of the U.S. Department

310 Guinier, Lani

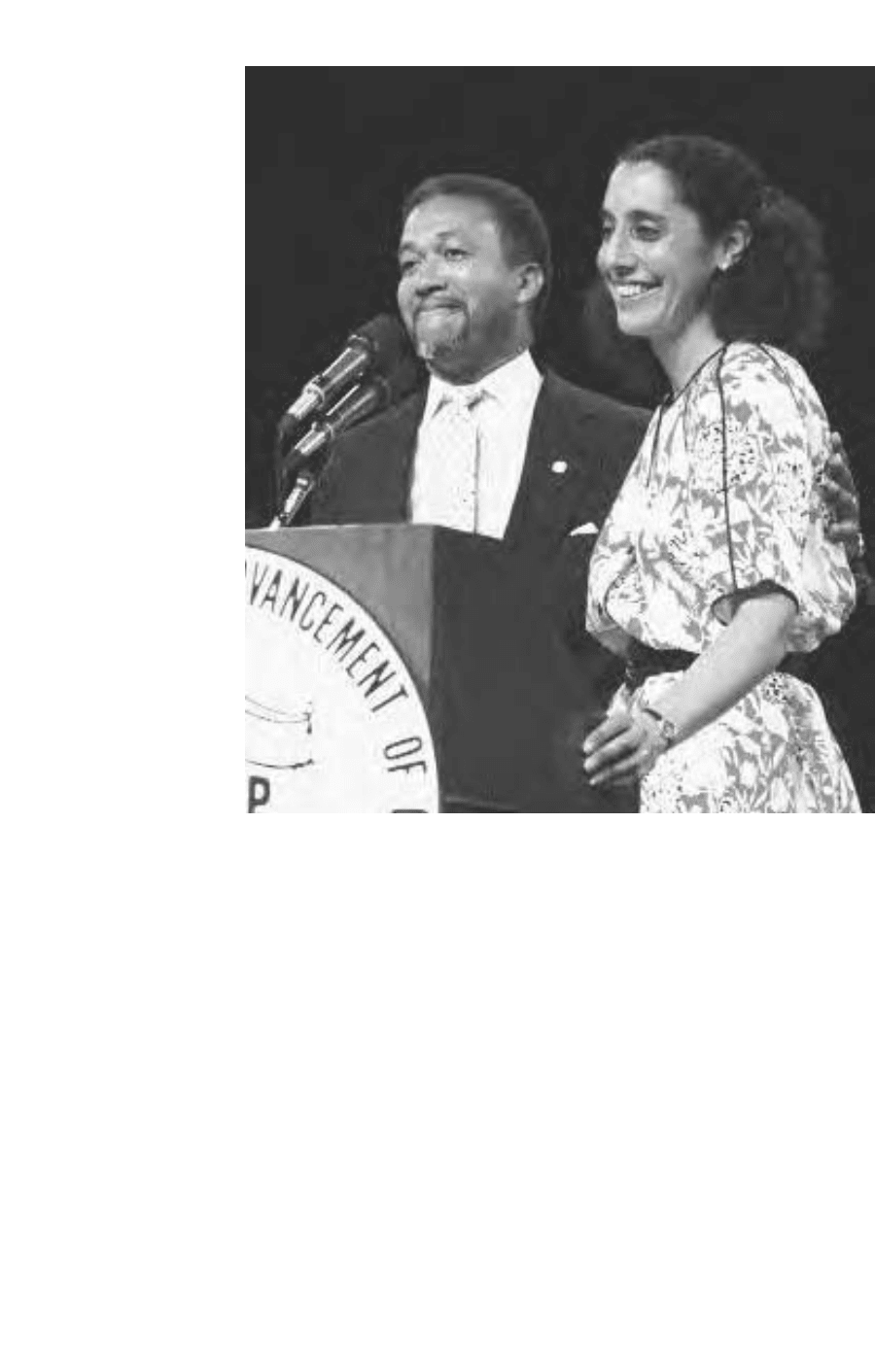

Lani Guinier, with

Benjamin Chavis,

executive director

of the National

Association for the

Advancement of

Colored People,

addressed the

NAACP convention

in Indianapolis, 1993

(Associated Press AP)

of Justice, and from 1981 to 1988, she worked for the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense and Education

Fund. She was an adjunct professor at the New York University School of

Law from 1985 to 1989 and became a law professor at the University of

Pennsylvania Law School in 1988.

Guinier wrote The Tyranny of the Majority (1994). She teaches at the

University of Pennsylvania Law School.

See also National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Women

in the

References Congressional Quarterly Almanac, 103rd Congress, 1st Session...1993

(1994).

Guinier, Lani 311

H. L. v. Matheson (1984)

In H. L. v. Matheson, the U.S. Supreme Court decided that a Utah law re-

quiring a physician to notify the parents of an immature, dependent mi-

nor woman before performing an abortion did not violate her right to

privacy. The Court said the law was constitutional because the parents did

not have to give their consent to the procedure but only had to be noti-

fied. Because the woman in the case did not assert that she was mature,

the Court did not rule on the law’s constitutionality if a mature minor

woman were seeking the procedure.

See also Abortion

References H. L. v. Matheson, 450 U.S. 398 (1984); www.naral.org.

Hall, Katie Beatrice Green (b. 1938)

Democrat Katie Hall of Indiana served in the U.S. House of Representa-

tives from 2 November 1982 to 3 January 1985. Hall entered politics as a

volunteer for Richard Hatcher’s campaigns for mayor of Gary, Indiana,

beginning in 1967 and through his 1975 campaign. She served in the In-

diana House of Representatives from 1973 to 1975 and the state Senate

from 1975 to 1982. She focused on education, labor, and women’s issues

and passed a measure that clarified the state’s divorce laws by defining

marital property. A strong advocate of the Equal Rights Amendment, she

successfully worked for Indiana’s ratification of it.

When the incumbent member of Congress died in the fall of 1982,

Mayor Hatcher, as chair of the district’s party organization, had the power

313

H

to name the Democratic candidate to fill the vacancy. He named Hall, who

ran simultaneously to complete the deceased member’s term and for a full

term of her own. Hall’s campaign issues included support for the expan-

sion of unemployment benefits, job training, and other forms of assis-

tance and opposition to unlimited military spending, high interest rates,

and economic programs that benefited large corporations at the expense

of middle-income people.

In Congress, Hall introduced and passed the bill that made Martin

Luther King, Jr.’s birthday a federal holiday. Measures for recognizing

King’s contributions to American civil rights had been introduced by oth-

ers for fifteen years, and support for the idea had been steadily building

when Hall introduced it. She also worked for programs to alleviate unem-

ployment, which was high in Indiana; to revitalize the steel industry; and

to prevent child abuse and family violence. Defeated in the 1984 primary,

she also failed in subsequent primaries in 1984 and 1990.

Born in Mound Bayou, Mississippi, African American Katie Hall re-

ceived her bachelor of science degree from Mississippi Valley State Uni-

versity in 1960 and her master of science degree from Indiana University

in 1968. She taught social studies from 1961 to 1975.

See also Congress, Women in; Equal Rights Amendment; State Legislatures,

Women in

References Catlin, “Organizational Effectiveness and Black Political Participation:

The Case of Katie Hall” (1985); Congressional Quarterly, Politics in America

1994 (1993).

Hamer, Fannie Lou Townsend (1917–1977)

One of the Deep South’s most influential African American civil rights

leaders, Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper, went into cotton fields and

soybean fields to urge African Americans to register to vote, defying sher-

iffs, landowners, and tradition. Powerful and compelling when she testi-

fied before the 1964 Democratic National Convention’s credentials com-

mittee, she described her attempts to register to vote and helped the

nation understand the cruelty and violence of racism. Hamer’s religious

faith sustained her through the physical violence she endured and the in-

juries that resulted. By expressing her faith through hymns of hope, sup-

plication, and praise, she shared her courage and strengthened others.

Born on a Montgomery County, Mississippi, plantation, Fannie Lou

Hamer began working in the fields picking cotton when she was six years

old. She had about six years of formal education. Her involvement in civil

rights began after she attended rallies organized by the Student Nonvio-

lent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at the Ruleville Baptist Church in

1962. She explained: “They talked about how it was our rights as human

314 Hamer, Fannie Lou Townsend