Schenken Suzanne O’Dea. From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics (2 Volumes)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

court dismissed her lawsuit on the ground that Title VII did not apply to

the selection of partners in a partnership. The U.S. Supreme Court dis-

agreed with the district court and said that Title VII covers partners in a

partnership and bans discrimination on the basis of race or sex.

See also Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII; Employment Discrimination

References Hishon v. King and Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984).

Hobby, Oveta Culp (1905–1995)

The first secretary of the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Wel-

fare, Democrat Oveta Culp Hobby was also the first director of the

Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps. Hobby began her public service career as

a dollar-a-year executive with the War Department in the women’s inter-

est section of the Bureau of Public Relations. The next year, she developed

plans for the newly created Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps and became

the first director of the corps in 1942, holding the rank of colonel. The

corps ended its auxiliary status in 1943 and became the Women’s Army

Corps (WAC) with full military status. Many of Hobby’s initial duties in-

volved establishing policies and procedures for military women, recruiting

them, and integrating them into the armed forces. She dealt with both

substantive and trivial issues. African Americans questioned how a south-

erner such as Hobby would deal with training and appointing officers,

prompting Hobby’s announcement that African American women would

be appointed officers in proportion to the number of African American

women in the general population. She appeared before Congress’s Military

Affairs Committee to gain approval for the positions women could hold in

the army and obtained its consent on 239 job classifications. Throughout

her tenure as head of the corps, Hobby fought sex biases. For example, the

military proposed dishonorable discharge for women who became preg-

nant without prior approval, but Hobby objected by proposing that men

who fathered children out of wedlock should also receive a dishonorable

discharge. Hobby won her point, and pregnant WACs received honorable

discharges. The press questioned her on whether or not women would be

able to wear makeup. Hobby concluded that they could wear modest

amounts of it. At the end of World War II, about 100,000 women had

served in the corps. In 1945, Hobby resigned and returned to Houston.

Although Hobby considered herself a conservative Democrat, she

supported Republican governor Thomas E. Dewey’s unsuccessful 1948

presidential campaign. As coeditor and publisher of the Houston Post, she

announced her support for Republican General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s

1952 presidential candidacy and spent several months in New York work-

ing in the Citizens for Eisenhower headquarters. After winning the election,

Hobby, Oveta Culp 335

Eisenhower appointed Hobby to head the Federal Security Agency, which

became the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW). As

secretary of HEW, Hobby supervised the development of nurse-training

programs and a hospital reinsurance program. Her most important con-

tribution was likely her decision to license six drug companies to manu-

facture the Salk vaccine for polio in 1955.

Born in Killeen, Texas, Hobby studied law at Mary Hardin–Baylor

College and completed her studies at the University of Texas Law School.

In 1919, when she was in high school, Hobby’s father was elected to the

Texas legislature, and she went with him to Austin to work for him. In

1925, she became parliamentarian of the Texas legislature, holding the po-

sition for six years, and served in the position again in 1939 and 1941. She

wrote Mr. Chairman, a textbook on parliamentary procedure, in 1937.

Married to former Texas governor and newspaper owner William

Pettis Hobby, Oveta Hobby was an editor and executive vice president of

the newspaper as well as executive director of a radio station her husband

owned. Following her retirement from government service, Hobby re-

turned to Houston and resumed her role in the newspaper and the fam-

ily’s other business enterprises.

See also Cabinets, Women in Presidential; Military, Women in the; Rogers,

Edith Frances Nourse

References Crawford and Ragsdale, Women in Texas (1992); H. W. Wilson,

Current Biography: Who’s News and Why, 1942 (1942), Current Biography:

Who’s News and Why, 1953 (1953); New York Times, 17 August 1995;

Schoenebaum, ed., Political Profiles: The Eisenhower Years (1977).

Hodgson v. Minnesota (1990)

Hodgson v. Minnesota challenged a 1981 Minnesota law requiring that the

parents of a female child under eighteen years of age be notified before she

could obtain an abortion. Under the law, both parents of the minor female

seeking an abortion had to be given notice forty-eight hours before the

procedure could be performed. The law included a judicial bypass proce-

dure, which meant that if the young woman did not wish to notify her

parents, she could go to a judge for notification. To obtain a court order,

the minor female had to prove that she was mature and capable of giving

informed consent. The law also specified exceptions to the two-parent no-

tification, including divorce; emergency treatment to save the woman’s

life; and sexual or physical abuse, in which case the proper authorities had

to have been notified.

Abortion clinics, physicians, pregnant minors, and others filed suit,

claiming the law violated the due process and equal protection clauses of

the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court invalidated the two-parent noti-

336 Hodgson v. Minnesota

fication without a judicial bypass procedure, saying that it had no rational

basis. The Court upheld the forty-eight-hour waiting period and the two-

parent notification that included a procedure for a judicial waiver.

See also Abortion; Fourteenth Amendment

References Hodgson v. Minnesota, 497 U.S. 417 (1990).

Holt, Marjorie Sewell (b. 1920)

Republican Marjorie Holt of Maryland served in the U.S. House of Rep-

resentatives from 3 January 1973 to 3 January 1987. Holt entered Congress

with an agenda of reducing nonmilitary spending and increasing military

spending, and in 1978 she introduced an alternative budget and came

within five votes of passing it. Holt continued to regularly develop and in-

troduce her Republican version of the budget, which became part of her

party’s national political strategy. She adamantly opposed school busing,

introduced measures to end it, and gained House approval for a constitu-

tional amendment to ban it.

Born in Birmingham, Alabama, Marjorie Holt earned her bachelor’s

degree from Jacksonville University in 1945 and her law degree from the

University of Florida in 1949. After several years in private law practice,

Holt was circuit court clerk for Anne Arundel County Court from 1966 to

1972. She served on the Maryland Governor’s Commission on Law En-

forcement and Administration of Justice from 1970 to 1972.

See also Congress, Women in

References Congressional Quarterly, Politics in America: Members of Congress

in Washington and at Home (1983); Office of the Historian, U.S. House of

Representatives, Women in Congress, 1917–1990 (1991).

Holtzman, Elizabeth (b. 1941)

Democrat Elizabeth Holtzman of New York served in the U.S. House of

Representatives from 3 January 1973 to 3 January 1981. When Holtzman

entered the 1972 Democratic primary, she challenged incumbent congress-

man Emanuel Celler, who had represented the district for fifty years. Celler,

whose campaign was well financed and whose campaign organization was

far more sophisticated than Holtzman’s, dismissed her candidacy. She con-

ducted a grassroots campaign, emphasized her opposition to the war in

Vietnam, argued that Celler had become removed from his constituency,

and pointed to the amount of time he was absent from Congress. Her vic-

tory in the primary election all but ensured her election to Congress.

Shortly after Holtzman entered Congress, President Richard Nixon

ordered the bombing of Cambodia, and she filed suit in U.S. district court

to stop the bombings. The court ordered them to stop, but the decision

Holtzman, Elizabeth 337

was overturned on appeal. She took the matter to the U.S. Supreme Court,

but her request for a hearing was denied.

In 1979, Holtzman discovered that fifty alleged Nazi war criminals

resided in the United States, and she began a crusade to have them de-

ported. For years, she challenged the Immigration and Naturalization Ser-

vice to respond to her demands for deportation action, and eventually

more than 100 Nazi war criminals were expelled from the United States.

A feminist, Holtzman was one of the organizers and one of the first

cochairs of the Congresswomen’s Caucus, later known as the Congres-

sional Caucus for Women’s Issues, created to bring women members of

Congress together to discuss matters of common interest. Holtzman

served on the President’s National Commission on the Observance of In-

ternational Women’s Year, the group that planned the 1977 National

Women’s Conference. A strong Equal Rights Amendment supporter,

Holtzman told one group: “Sooner or later, inevitably and inexorably, our

Constitution will embody the principle of women’s equality under the

law.” In 1978, she passed a bill that helped protect the privacy of rape vic-

tims by preventing cross-examination into their prior sexual experience.

Holtzman entered the 1980 Democratic primary for the U.S. Senate

instead of running for a fifth term. She won the primary but lost the gen-

eral election. In 1981, Holtzman won the race for district attorney of

Brooklyn, where she served until 1989, the year she was elected comptrol-

ler of New York City. After serving from 1990 to 1994, she returned to pri-

vate law practice.

Born in New York, New York, Holtzman received her bachelor’s de-

gree from Radcliffe College in 1962 and her law degree from Harvard Law

School in 1965. While in law school, she spent the summer of 1963 in

Georgia working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee,

a civil rights organization. The next summer she worked for the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense and

Education Fund.

See also Congress, Women in; Congressional Caucus for Women’s Issues; Equal

Rights Amendment; Heckler, Margaret Mary O’Shaughnessy; National

Women’s Conference

References Holtzman, Who Said It Would Be Easy: One Woman’s Life in the Po-

litical Arena (1996); Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives,

Women in Congress, 1917–1990 (1991).

Honeyman, Nan Wood (1881–1970)

Democrat Nan Honeyman of Oregon served in the U.S. House of Repre-

sentatives from 3 January 1937 to 3 January 1939. Honeyman strongly

supported New Deal policies and was accused of subordinating her dis-

338 Honeyman, Nan Wood

trict’s needs to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s national political con-

cerns. She was defeated in her attempt for a second term in 1938 and in

1940. She was senior representative for the Pacific Coast of the Office of

Price Administration in 1941 and 1942 and collector of customs for Port-

land, Oregon, from 1942 to 1953.

Born in West Point, New York, Nan Honeyman graduated from St.

Helens Hall in 1898 and later attended Finch School in New York to study

music. Honeyman served in the Oregon House of Representatives from

1935 to 1937 and filled a vacancy in the Oregon Senate in 1942.

See also Congress, Women in; State Legislatures, Women in

References Office of the Historian, U.S. House of Representatives, Women in

Congress, 1917–1990 (1991).

hooks, bell (b. 1952)

African American intellectual bell hooks has criticized the feminist move-

ment for its racism and has argued that it must recognize that women

have a variety of backgrounds and experiences and that race and class af-

fect women’s lives as much as gender. She seeks to understand race, gen-

der, and class biases by beginning with her own experiences and the expe-

riences of other women and developing theories from them. She further

seeks to use her theories to alter the ways people live their lives, which she

calls the practical phase of her work. To involve a larger audience than ac-

ademics, hooks uses popular culture to link familiar movies or books to

theory, providing a base from which to engage students and readers and

then move them to considering theory.

College professor and mentor, hooks has published several works, in-

cluding Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (1981); Feminist

Theory from Margin to Center (1984); Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural

Politics (1990); Breaking Bread: Insurgent Black Intellectual Life (1991); and

Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (1994).

Born in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, bell hooks was given the name Glo-

ria Jean Watkins, taking her maternal great-grandmother’s name when

she began her writing career. She uses lowercase letters instead of capital

letters because she believes that who has written something is less impor-

tant than what they have written. hooks completed her undergraduate

studies at Stanford University in 1973 and earned her master’s degree

from the University of Wisconsin in 1976 and her doctoral degree from

the University of California at Santa Cruz in 1983. She has taught at vari-

ous California universities, Yale University, Oberlin College, and the City

College of New York.

See also Feminist Movement

hooks, bell 339

References H. W. Wilson, Current Biography Yearbook, 1995 (1995); hooks, with

Mckinnon, “Sisterhood: Beyond Public and Private” (1996).

Hooley, Darlene (b. 1939)

Democrat Darlene Hooley of Oregon entered the U.S. House of Repre-

sentatives on 3 January 1997. During her congressional campaign, Hooley

pledged to work for income tax deductions for college tuition and for im-

proved vocational programs for people needing professional retraining.

Hooley’s congressional priorities include protecting funding for early

childhood education, preserving Social Security and Medicare, and pro-

tecting abortion rights.

Hooley became an activist for safer playgrounds in the 1970s,

served on the park district board, and then served on the West Linn City

Council from 1977 to 1981. While in the Oregon State House of Repre-

sentatives from 1981 to 1987, she passed welfare reform legislation that

moved people from welfare to work. She authored the state’s first recy-

cling laws, rewrote the state’s land use laws, and wrote and passed equal

pay laws.

Hooley accepted an appointment to fill a vacancy on the Clackamas

County Commission in 1987 and then won reelection to it until 1996. On

the commission, she worked to improve county roads, implement welfare

reform, increase the number of police, and create new jobs in the private

sector. She helped establish a pilot project in which welfare recipients re-

ceived counseling to reduce the number of people on welfare assistance.

Born in Williston, North Dakota, Darlene Hooley attended Pasadena

Nazarene College from 1957 to 1959 and received her bachelor’s degree

from Oregon State University in 1961.

See also Congress, Women in

References Congressional Quarterly, Politics in America 1998 (1997);

www.house.gov/hooley.

Horn, Joan Kelly (b. 1936)

Democrat Joan Horn of Missouri served in the U.S. House of Representa-

tives from 3 January 1991 to 5 January 1993. Horn was active in the

Democratic Party, the Missouri Women’s Political Caucus, and the Free-

dom of Choice Council, connections that provided her with an important

network when she sought a seat in Congress, her first political office. In

addition, she and her husband were partners in a research and polling

firm, which gave her additional political experience. She lost reelection at-

tempts in 1992 and 1996.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri, Joan Horn earned her bachelor’s degree

340 Hooley, Darlene

in 1973 and her master’s degree in 1975 from the University of Missouri

at St. Louis.

See also Congress, Women in

References Congressional Quarterly, Politics in America 1992 (1991).

Howe, Julia Ward (1819–1910)

Best known for writing “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Julia Ward Howe

provided leadership in the areas of woman suffrage, women’s education,

and peace. Married in 1843 to social reformer Dr. Samuel Gridley Howe,

she bore six children in the next sixteen years. In addition to caring for

them, she attended lectures; studied foreign languages, religion, and phi-

losophy; and wrote poetry and dramas, interests she developed because

her husband did not want her involved in public life.

Julia Howe’s entrance into public life began when she anonymously

published Passion-Flowers, a collection of poems in 1854, and a second

collection, Words for the Hour, in 1857. She wrote “The Battle Hymn of the

Republic” in 1861, Atlantic Monthly published it in 1862, and it became a

Civil War anthem. With its success, Julia Howe actively engaged in her lit-

erary career, publishing a literary magazine in 1867.

She also became active in the woman suffrage movement. In 1868, she

was a founder and the first president of the New England Woman Suffrage

Association, serving until 1877 and again from 1893 to 1910. She became

a leader in the newly organized American Woman Suffrage Association in

1869. President of the Massachusetts Woman Suffrage Association from

1870 to 1877 and from 1891 to 1893, she founded a weekly woman suffrage

magazine, Woman’s Journal, in 1870, and edited it for twenty years.

Also in 1870, she wrote “Appeal to Womanhood throughout the

World,” a call to women to become active in peace issues. She organized

the Woman’s Peace Conference in London in 1872.

Howe’s husband died in 1876 and with her new freedom, she went

on her first speaking tour that year, advocating the development of a na-

tional women’s club movement. A founder of the New England Women’s

Club in 1868, she was its president for most of the rest of her life, begin-

ning in 1870. She was also a founder of the General Federation of

Women’s Clubs in 1890.

In addition to her commitments to woman suffrage and the women’s

club movement, Howe continued her literary career, publishing collec-

tions of her lectures, a biography of Margaret Fuller, and her memoirs.

See also American Woman Suffrage Association; General Federation of

Women’s Clubs; Peace Movement; Suffrage

References Garraty and Carnes, eds., American National Biography (1999).

Howe, Julia Ward 341

Hoyt v. Florida (1961)

The U.S. Supreme Court decided in Hoyt v. Florida that being judged by an

all-male jury did not violate an accused person’s Fourteenth Amendment

rights. At the time, women could not serve on state juries in three states,

and in twenty-six states and the District of Columbia women could claim

exemptions not available to men. In Florida, women who wanted to serve

on a jury had to register with the clerk of the circuit court, which few did.

In Hoyt, a woman convicted of killing her husband appealed on the

grounds that she had been denied her Fourteenth Amendment rights be-

cause Florida’s law unconstitutionally excluded women from jury service.

The woman argued that her case demanded women on the jury because

women would have been more sympathetic than men in considering her

temporary insanity defense.

The Court rejected her appeal, saying first that “woman is still re-

garded as the center of home and family life. We cannot say that it is con-

stitutionally impermissible for a State, acting in pursuit of the general wel-

fare, to conclude that a woman should be relieved from the civic duty of

jury service unless she herself determines that such service is consistent

with her own special responsibilities.” From that perspective, the Court

said that it was reasonable “for a state legislature to [assume] that it would

not be administratively feasible to decide in each individual instance

whether family responsibilities of a prospective female juror were serious

enough to warrant an exemption.”

In 1975, the Court overturned this decision in Taylor v. Louisiana.

See also Fourteenth Amendment; Juries, Women on; Taylor v. Louisiana

References Getman, “The Emerging Constitutional Principle of Sexual Equal-

ity” (1973); Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U.S. 57 (1961).

Huck, Winifred Sprague Mason (1882–1936)

Republican Winifred Huck of Illinois served in the U.S. House of Repre-

sentatives from 7 November 1922 to 3 March 1923. The daughter of Con-

gressman William Mason, who died in office, Winifred Huck won the spe-

cial election to fill the vacancy. She introduced legislation to grant

independence to the Philippine Islands, to grant self-government to Cuba

and Ireland, and to require a direct popular vote before U.S. armed forces

could be involved in an overseas war. She was denied the party’s nomina-

tion for the full term that began in 1923.

In 1925, Huck investigated the criminal justice system and prisons.

With the cooperation of Ohio’s governor, she was arrested for a minor

crime, convicted, incarcerated for a month, and pardoned by the gover-

nor. She then began a trip to New York, seeking employment as an ex-

342 Hoyt v. Florida

convict along the way and writing a series of syndicated articles about her

experiences. In 1928 and 1929, she was an investigative reporter for

Chicago Evening Post.

Huck was born in Chicago, Illinois.

See also Congress, Women in

References James, ed., Notable American Women 1607–1950 (1971); New York

Times, 26 August 1936.

Huerta, Dolores (b. 1930)

Dolores Huerta has sought economic and employment justice for His-

panic American agricultural workers since the early 1960s, when she and

Cesar Chavez cofounded the National Farm Workers Association

(NFWA). A folk hero in the Mexican American community for her work

as a contract negotiator, strike organizer, lobbyist, and boycott coordina-

tor, Huerta has been arrested more than two dozen times and has experi-

enced harassment and violence.

Huerta entered the migrant labor movement in part out of frustra-

tion at teaching migrants’ children because, she later explained:“I couldn’t

stand seeing kids come to class hungry and needing shoes. I thought I

could do more by organizing farm workers than by trying to teach their

hungry kids.” In 1955, she met a representative of the Community Service

Organization (CSO), a Mexican American self-help association that

sought to empower Latinos through political action. A founding member

of the Stockton, California, CSO, Huerta served as the group’s lobbyist to

the California legislature in the late 1950s and early 1960s. She helped pass

more than a dozen bills, including measures requiring businesses to pro-

vide pensions to legal immigrants and allowing farmworkers to receive

public assistance, retirement benefits, and disability and unemployment

insurance regardless of their status as U.S. citizens.

Through CSO, Huerta worked with Chavez, who proposed creating a

union for farmworkers. In 1962, they formed the NFWA, went into fields,

and explained the anticipated benefits of organizing to farmworkers.

Chavez and Huerta endured threats from landowners and law enforcement

officers. When the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial

Organizations (AFL-CIO) initiated a strike against California grape grow-

ers, the NFWA joined the effort in 1965. The AFL-CIO group and the

NFWA merged into the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee

(UFWOC) in 1966. For her involvement in the strike as an organizer,

Huerta was repeatedly arrested and placed under surveillance by the Cen-

tral Intelligence Agency.

Huerta was named chief negotiator for UFWOC, even though she was

Huerta, Dolores 343

not a lawyer, had no experience as a labor negotiator, and had never read a

union contract before the strike began. By 1967 she had negotiated con-

tracts that gave workers an hourly raise, health care benefits, job security,

and protection from pesticide poisoning. Despite the success with some

growers, the majority resisted the UFWOC, and the organization called for

a national boycott of table grapes in 1968. As director of the boycott,

Huerta moved to New York and mobilized unions, political activists, His-

panic associations, community organizations, and others in support of the

boycott, one of the most successful boycotts in the United States. In 1970,

Huerta negotiated collective bargaining agreements with more than two

dozen growers and obtained many new benefits for grape workers. The suc-

cess attracted new members to UFWOC, and membership reached 80,000.

In 1972, the UFWOC became an independent affiliate of the AFL-CIO and

was renamed the United Farm Workers of America, AFL-CIO (UFW).

More boycotts followed in the 1970s, with Huerta managing the let-

tuce, grape, and Gallo wine boycotts. One of the successes of the boycotts

was the passage of the Agricultural Labor Relations Act in 1975, the first

law that recognized collective bargaining rights of California farmworkers.

Huerta described the achievements of the organizing efforts: “I think

we brought to the world, the United States, anyway, the whole idea of boy-

344 Huerta, Dolores

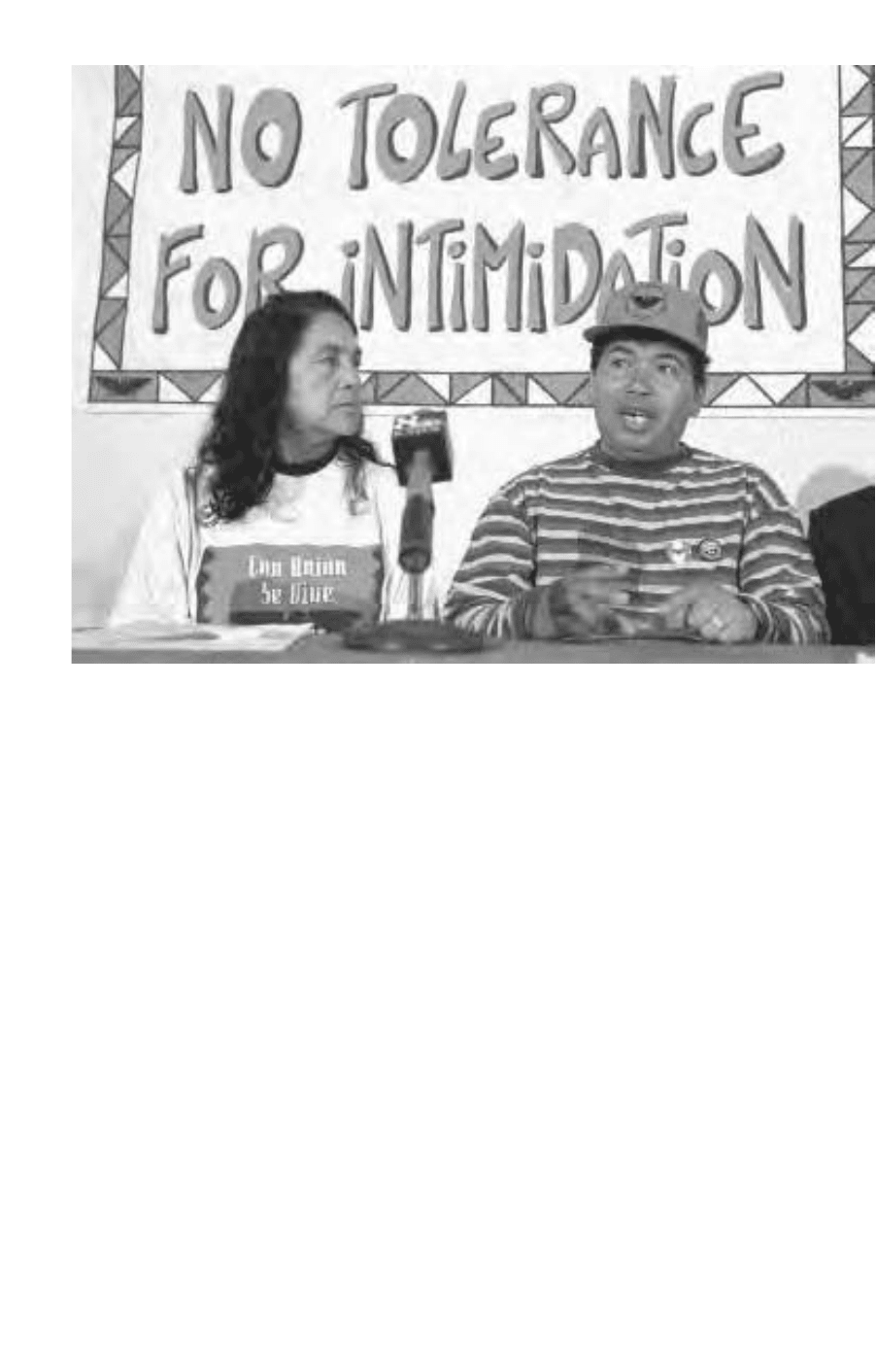

Dolores Huerta,

cofounder of the

United Farmworkers

of America, with

raspberry worker

Valentin Leon during

a lawsuit against a

California grower

(Associated Press AP)