Satas D., Tracton A.A. (ed.). Coatings Technology Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

852

A.

FElST

EDGE-GRAINED

B.

CROSS SECTION

OF

LOG

FLAT-GRAINED

Figure

2

Edge-grained

(or

vertical-grained

or

quartcrsawed) board

A.

and

flat-graincd

(or

slash-

grained or

plainsawed)

board

B,

cut

from

a

log.

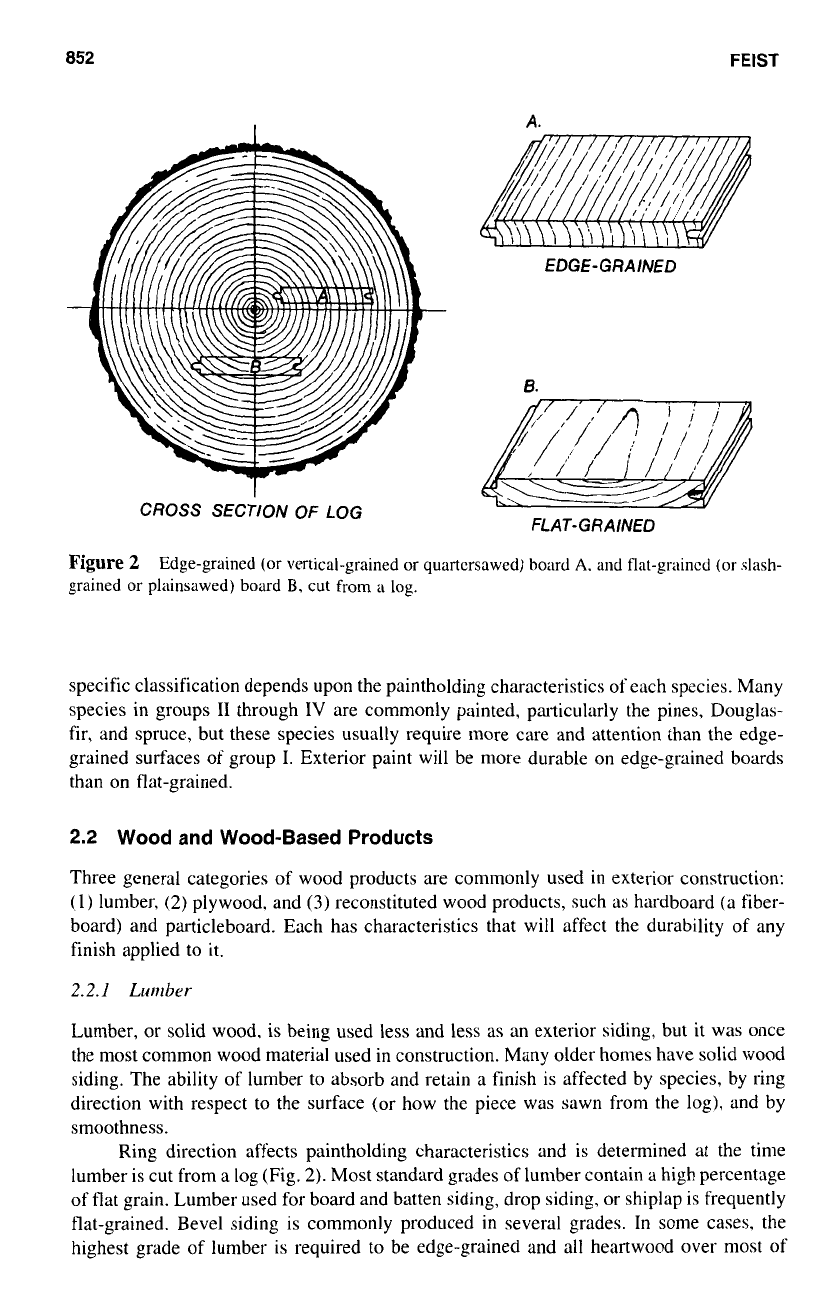

specific classification depends upon the paintholding characteristics

of

each species. Many

species in groups

I1

through

IV

are commonly painted, particularly the pines, Douglas-

fir, and spruce, but these species usually require more care and attention than the edge-

grained surfaces of group

I.

Exterior paint will be more durable

on

edge-grained boards

than on flat-grained.

2.2 Wood

and

Wood-Based

Products

Three general categories of wood products are commonly used in exterior construction:

(1)

lumber,

(2)

plywood. and

(3)

reconstituted wood products, such as hardboard (a fiber-

board) and particleboard. Each has characteristics that will affect the durability of any

finish applied to it.

2.2.1

Lumber

Lumber, or solid wood, is being used less and less

as

an exterior siding, but it was once

the most common wood material used in construction. Many older homes have solid wood

siding. The ability of lumber to absorb and retain a finish is affected by species, by ring

direction with respect

to

the surface (or how the piece was sawn from the log), and by

smoothness.

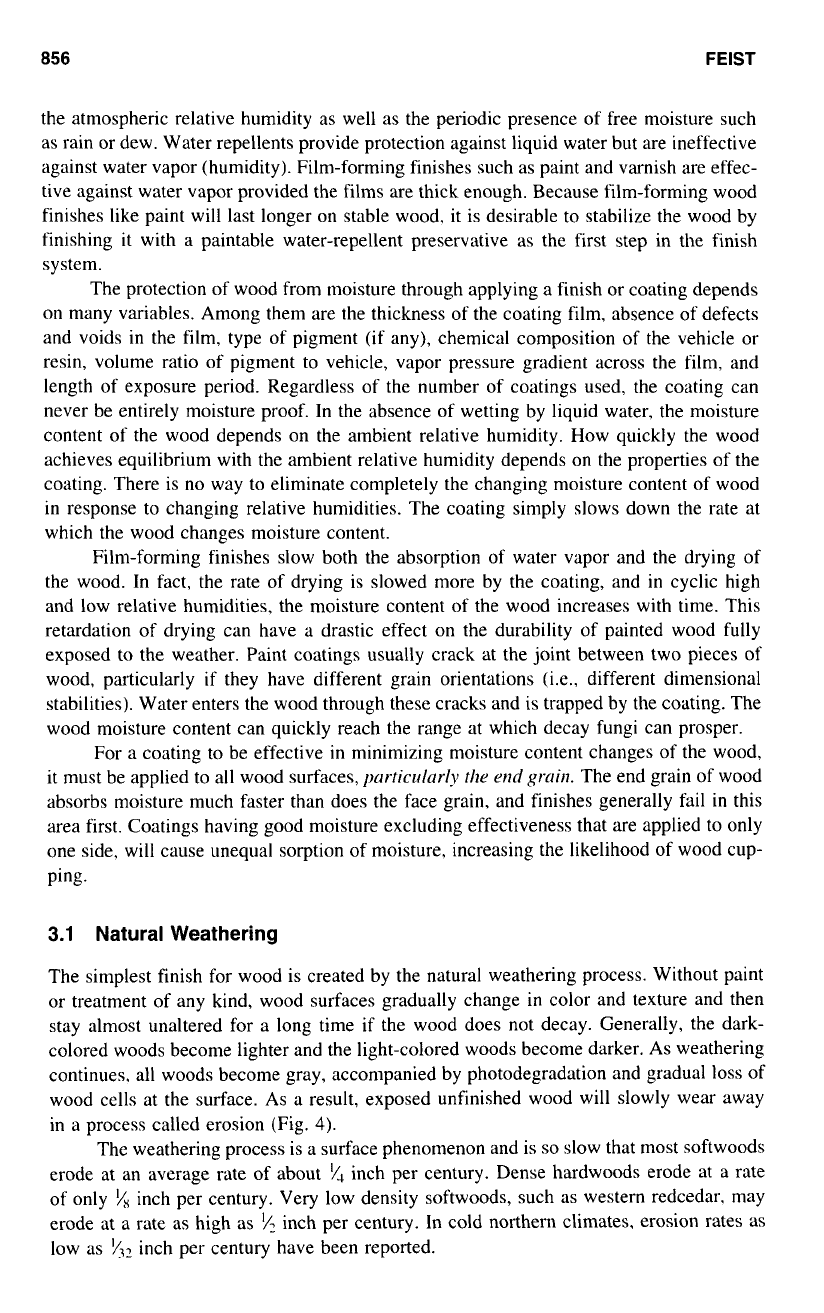

Ring direction affects paintholding characteristics and is determined at the time

lumber is cut from a

log

(Fig.

2).

Most standard grades of lumber contain a high percentage

of

flat grain. Lumber used for board and batten siding, drop siding, or shiplap is frequently

flat-grained. Bevel siding is commonly produced

in

several grades.

In

some cases, the

highest grade

of

lumber is required

to

be edge-grained and all heartwood over most

of

EXTERIOR

WOOD

FINISHES

853

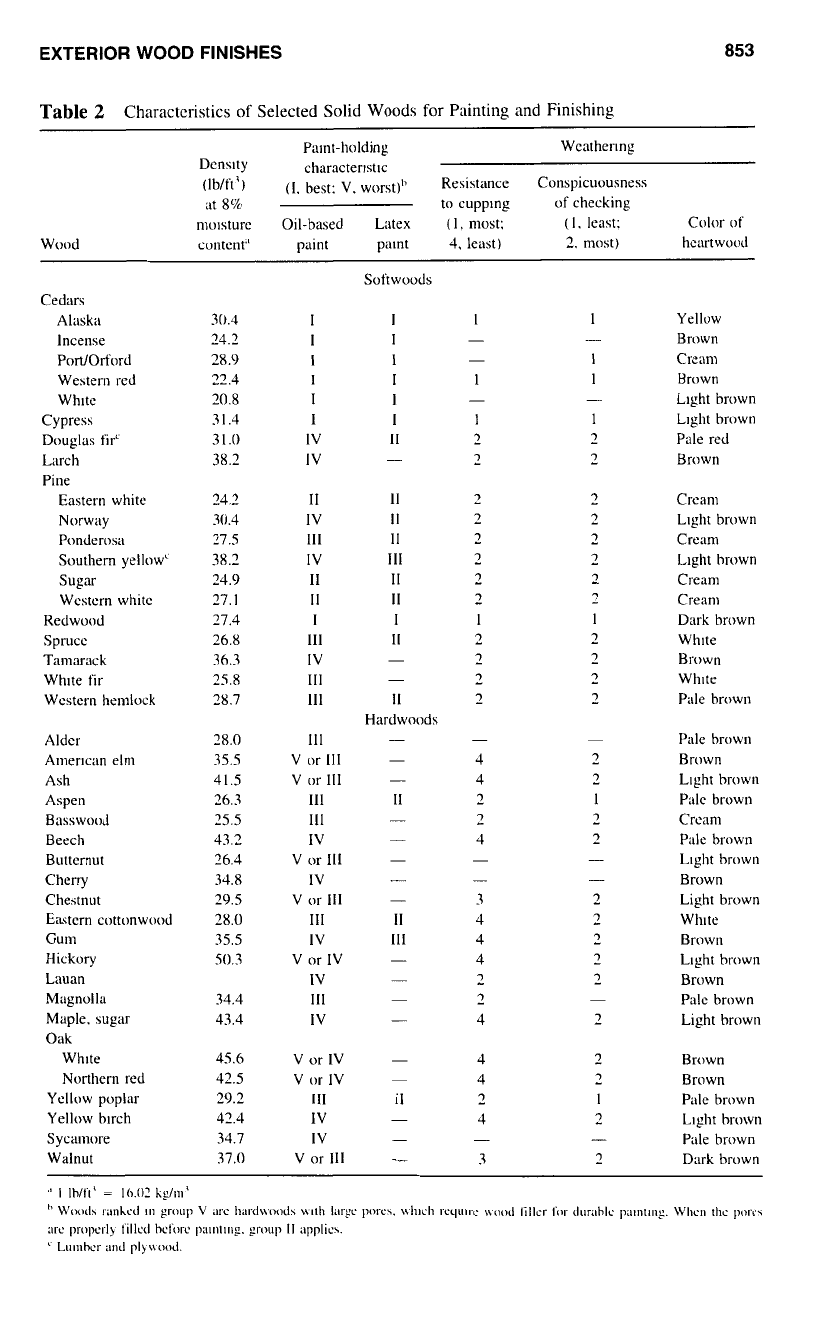

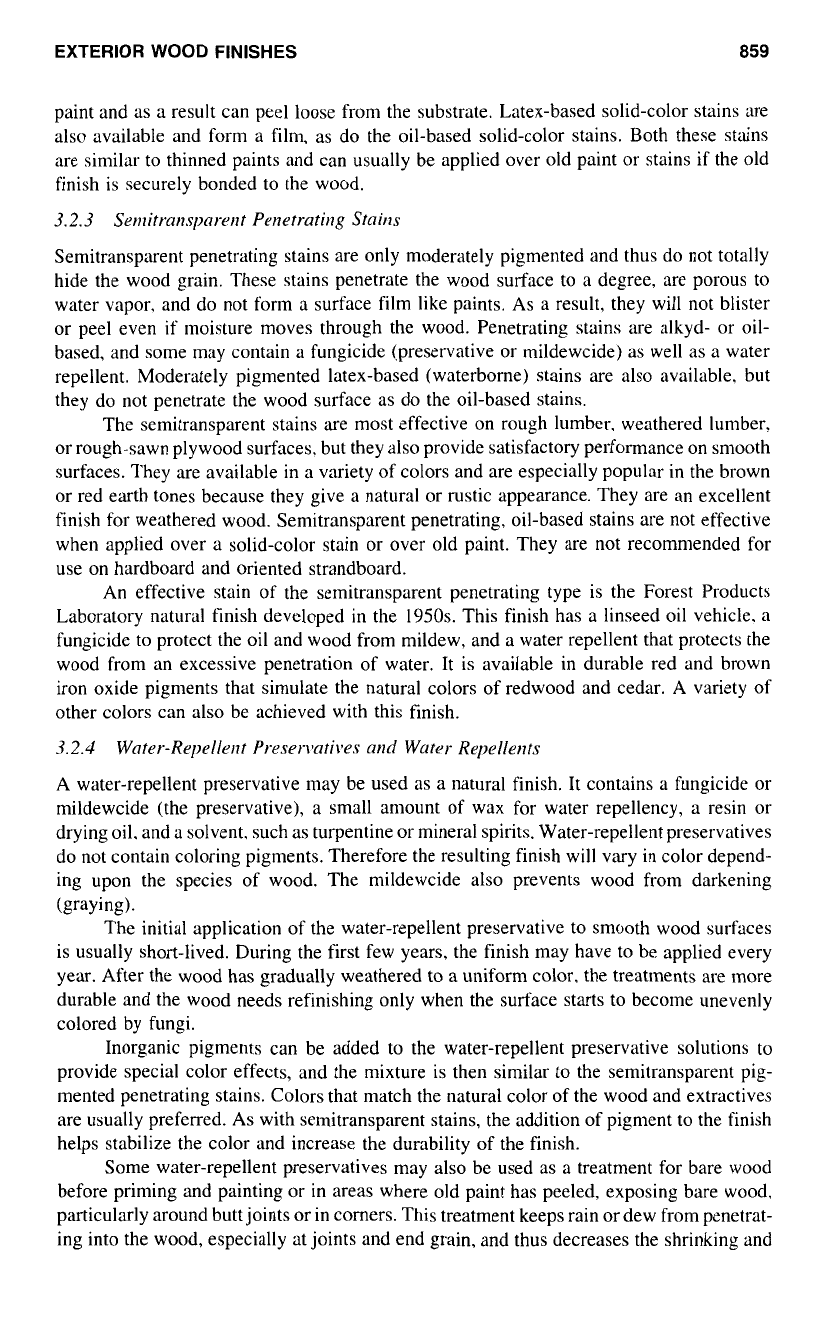

Table

2

Charactcristics

of

Selected Solid

Woods

for Painting

and

Finishing

Pam-holding Wcatherlng

Dcnslty

(Ib/ft')

(1.

best:

V,

worst)t~

Resistance Conspicuousness

characterlstlc

at

8%

to cupplng of checking

nwsture Oil-based Latex

(

I,

nut:

(I.

least: Color

of

Wood

content" paint pamt

4*

least)

2.

most) heartwood

Cedars

Alaska

Incense

Podorford

Western red

Whltc

Cypress

Douglas fir'

Larch

Pine

Eastern white

Norway

Ponderosa

Southern yellow'

Sugar

Western white

Redwood

Spruce

Tamarack

Whlte fir

Wcstern hemlock

Alder

Amerlcan elm

Ash

Aspen

Beech

Butternut

Cherry

Chestnut

Eastern cottonwood

Gum

Hickory

Lauan

Magnolln

Maple. sugar

Oak

B, 'Isswood

..

Whlte

Northern red

Yellow poplar

Yellow blrch

Sycamore

Walnut

30.4

24.2

28.9

22.4

20.8

3

I

.4

3

I

.o

38.2

24.2

30.4

27.5

38.2

24.9

27.1

27.4

26.8

36.3

25.8

28.7

28.0

35.5

41.5

26.3

25.5

43.2

26.4

34.8

29.5

28.0

35.5

50.3

34.4

43.4

45.6

42.5

29.2

42.4

34.7

37.0

Softwoods

I

I

I

I

I

l

I

I

I

1

I

I

IV

I1

IV

-

I1

II

IV

II

111

II

IV

111

II

II

II

II

I

1

111

II

IV

111

111

I1

Hardwoods

-

-

111

V

or

Ill

v

or

111

-

-

-

111

II

111

IV

V

or

111

IV

__

-

-

-

V

or

111

-

Ill

II

IV

111

V

or

IV

IV

Ill

IV

-

__

-

-

V

or

IV

-

V

or

IV

~

111

II

IV

IV

V

or

111

-

-

-

Yellow

Brown

Cream

Brown

Llght brown

Llght brown

Pale red

Brown

Cream

Llght brown

Crenm

Llght brown

Cream

Cream

Dark

brown

Whlte

Brown

Whlte

Pale brown

Pale brown

Brown

Llght brown

Pale

brown

Crcam

Pale

brown

Llght brown

Brown

Light brown

White

Brown

Llght brown

Brown

Pale brown

Light brown

Brown

Brown

Pale

brown

Llght brown

Pale

brown

Dark brown

854

FElST

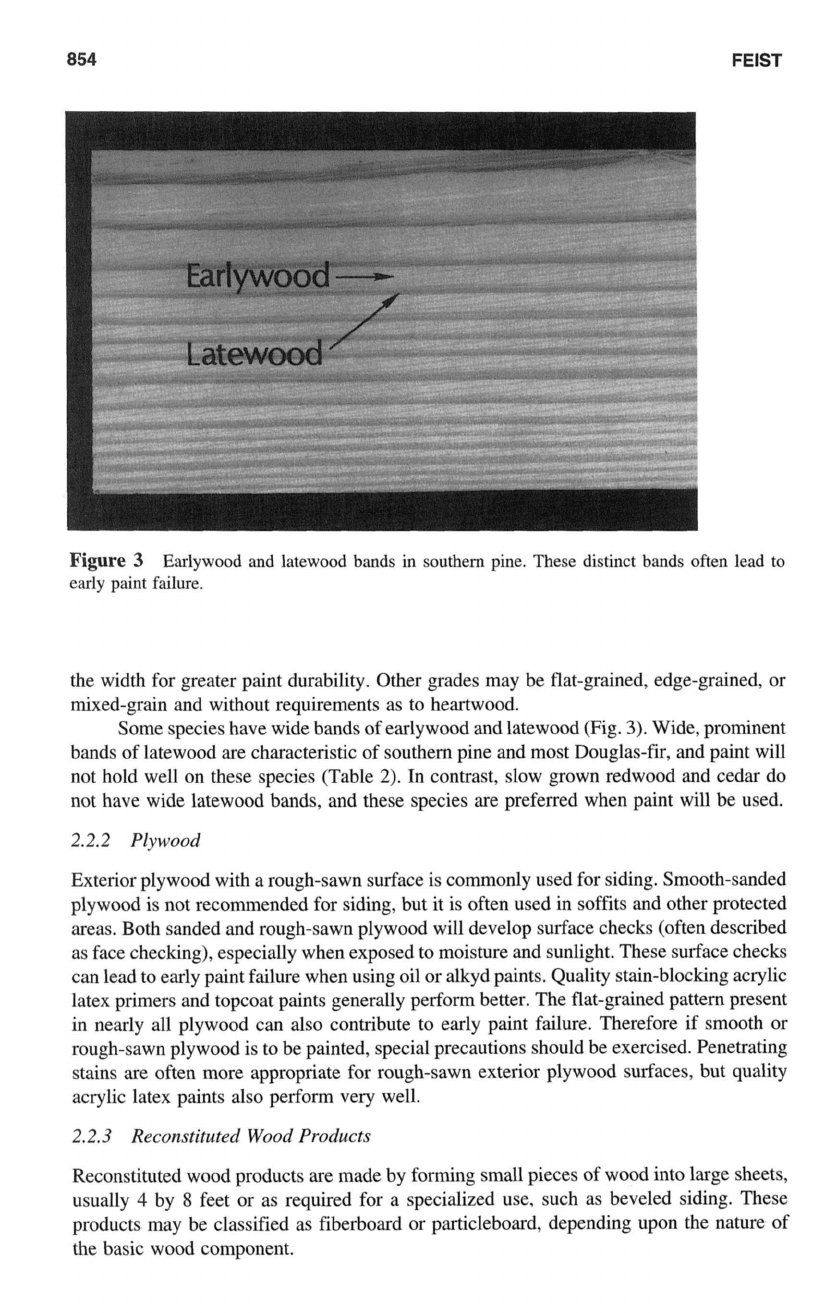

Figure

3

Earlywood and latewood bands in southern pine. These distinct bands often lead to

early paint failure.

the width for greater paint durability. Other grades may be flat-grained, edge-grained,

or

mixed-grain and without requirements as to heartwood.

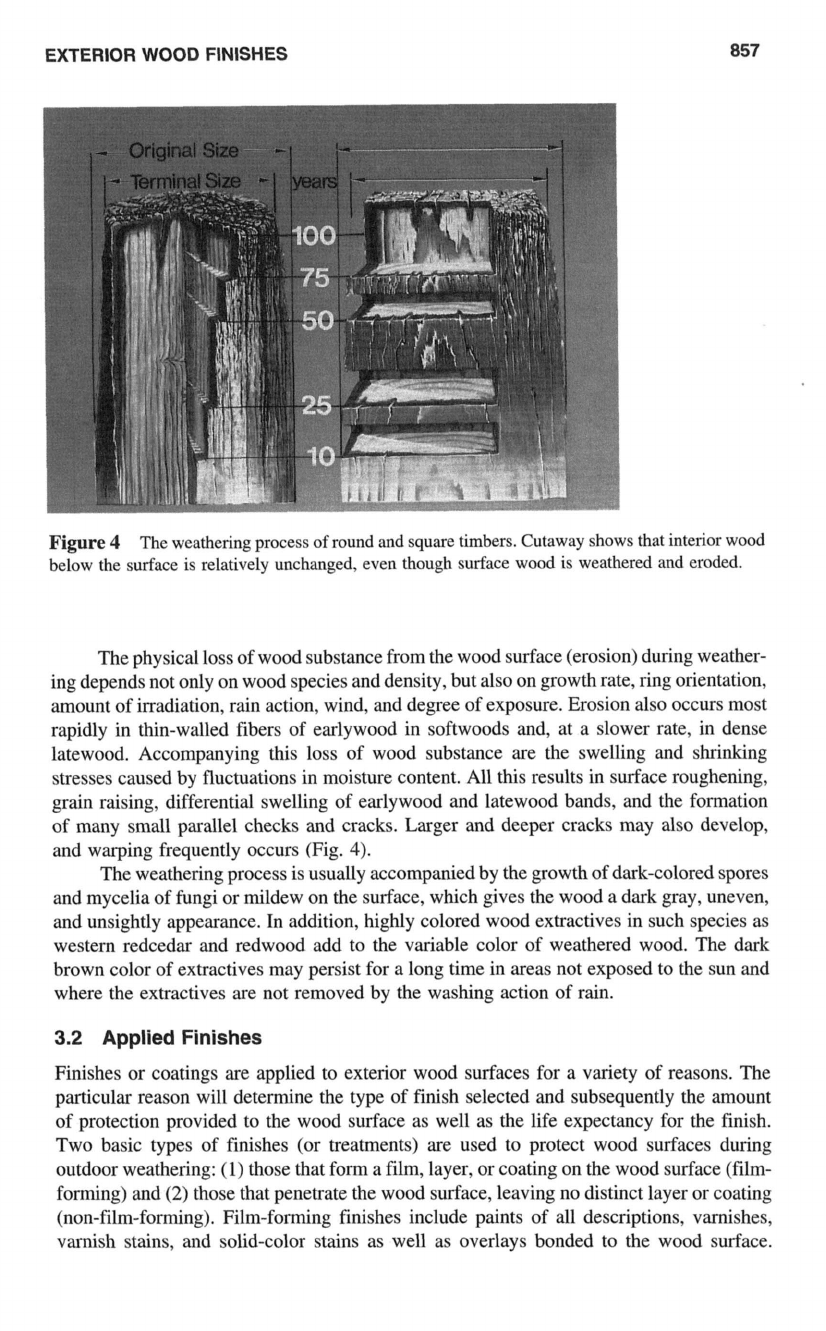

Some species have wide bands of earlywood and latewood (Fig.

3).

Wide, prominent

bands of latewood

are

characteristic of southern pine and most Douglas-fir, and paint will

not hold well on these species (Table

2).

In contrast, slow grown redwood and cedar do

not have wide latewood bands, and these species are preferred when paint will be used.

2.2.2

Plywood

Exterior plywood with a rough-sawn surface is commonly used for siding. Smooth-sanded

plywood is not recommended for siding, but it is often used

in

soffits and other protected

areas. Both sanded and rough-sawn plywood will develop surface checks (often described

as face checking), especially when exposed to moisture and sunlight. These surface checks

can lead to early paint failure when using oil

or

alkyd paints. Quality stain-blocking acrylic

latex primers and topcoat paints generally perform better. The flat-grained pattern present

in nearly all plywood can

also

contribute to early paint failure. Therefore if smooth

or

rough-sawn plywood is to be painted, special precautions should be exercised. Penetrating

stains are often more appropriate for rough-sawn exterior plywood surfaces, but quality

acrylic latex paints also perform very well.

2.2.3

Reconstituted Wood Products

Reconstituted wood products are made by forming small pieces of wood into large sheets,

usually

4

by

8

feet

or

as required for a specialized use. such as beveled siding. These

products may be classified as fiberboard

or

particleboard, depending upon the nature of

the basic wood component.

EXTERIOR

WOOD

FINISHES

855

Fiberboards are produced from mechanical pulps. Hardboard is a relatively heavy

type of fiberboard. and its tempered or treated form, designed for outdoor exposure. is

used for exterior siding. It is often sold in

4-

by Hoot sheets as

a

substitute for solid

wood beveled siding.

Particleboards are manufactured from whole wood in the form

of

splinters, chips,

flakes. strands.

or

shavings. Waferboard. oriented strandboard, and flakeboard are three

types

of

particleboard made from relatively large flakes or shavings.

Some fiberboards and particleboards are manufactured for exterior use. Film-forming

finishes, such as paints and solid-color stains. will give the most protection to these recon-

stituted wood products. Some reconstituted wood products may be factory-primed with

paint, and some may even have

a

factory-applied topcoat.

Also,

some may be overlaid

with

a

resin-treated cellulose fiber sheet to provide

a

superior surface for paint.

2.3

Water-Soluble Extractives

Water-soluble extractives are extraneous materials that are naturally deposited in the lu-

mens, or cavities, of cells

in

the heartwood of both softwoods and hardwoods. They are

particularly abundant

in

those woods commonly used for exterior applications, such

as

western red cedar, redwood, and cypress. and are

also

found in lesser amounts in Douglas-

fir and southern yellow pine heartwood. The attractive color, good dimensional stability,

and natural decay resistance of many species are due to the presence of extractives. How-

ever. these same extractives can cause serious finishing defects both at the time of finish

application and later. Because the extractives are water soluble, they can be dissolved

when free water is present and subsequently transported to the wood surface. When this

solution

of

extractives reaches the painted surface, the water evaporates, and the extractives

remain

as

reddish-brown marks.

Pitch in most pines and Douglas-fir can be exuded from either sapwood or heartwood.

Pitch is usually

a

mixture of rosin and turpentine; this mixture is called resin. Rosin is

brittle and remains solid at most normal temperatures. Turpentine, on the other hand, is

volatile even at relatively low temperatures. By use

of

the proper kiln-drying techniques,

turpentine can generally be driven from the wood, leaving behind only the solid rosin.

However, for green (wet) lumber or even dried lumber marketed for general construction,

different kiln schedules may be used, and the turpentine remains in the wood, mixed with

the rosin. The resultant resin melts at a much lower temperature than does pure rosin. and

consequently the mixture can move

to

the surface. If the surface is finished, the resin may

exude through the coating or cause

it

to

discolor or blister.

In

some species

of

wood the heartwood contains water-soluble extractives, while

sapwood does not. These extractives can occur in both hardwoods and softwoods. Western

redcedar and redwood are two common softwood species used

in

construction that contain

large quantities of extractives. The extractives give these species their attractive color,

good stability, and natural decay resistance, but they can also discolor paint. Woods such

as Douglas-fir and southern yellow pine

also

contain extractives that can cause occasional

extractive staining problems.

3.0

EXTERIOR

FINISHES

The various dimensions of wood and wood-based building materials are constantly chang-

ing because of changes

in

moisture content, which in turn are caused by fluctuations in

856

FEET

the atmospheric relative humidity as well

as

the periodic presence of free moisture such

as

rain or dew. Water repellents provide protection against liquid water but are ineffective

against water vapor (humidity). Film-forming finishes such

as

paint and varnish are effec-

tive against water vapor provided the films are thick enough. Because film-forming wood

finishes like paint will last longer on stable wood, it

is

desirable to stabilize the wood by

finishing it with

a

paintable water-repellent preservative

as

the first step in the finish

system.

The protection of wood from moisture through applying

a

finish or coating depends

on

many variables. Among them are the thickness of the coating film, absence of defects

and voids in the film, type of pigment (if any), chemical composition

of

the vehicle or

resin, volume ratio of pigment to vehicle, vapor pressure gradient across the film, and

length of exposure period. Regardless of the number of coatings used, the coating can

never be entirely moisture proof. In the absence of wetting by liquid water, the moisture

content

of

the wood depends on the ambient relative humidity. How quickly the wood

achieves equilibrium with the ambient relative humidity depends on the properties of the

coating. There is no way to eliminate completely the changing moisture content of wood

in response to changing relative humidities. The coating simply slows down the rate at

which the wood changes moisture content.

Film-forming finishes slow both the absorption of water vapor and the drying

of

the wood. In fact, the rate of drying is slowed more by the coating, and

in

cyclic high

and low relative humidities, the moisture content

of

the wood increases with time. This

retardation of drying can have a drastic effect

on

the durability of painted wood fully

exposed to the weather. Paint coatings usually crack at the joint between two pieces of

wood, particularly

if

they have different grain orientations (i.e., different dimensional

stabilities). Water enters the wood through these cracks and is trapped by the coating. The

wood moisture content can quickly reach the range at which decay fungi can prosper.

For a coating to be effective in minimizing moisture content changes of the wood,

it must be applied to all wood surfaces,

prticulurl~~ the

erld

grl1in.

The end grain

of

wood

absorbs moisture much faster than does the face grain, and finishes generally fail

in

this

area first. Coatings having good moisture excluding effectiveness that are applied to only

one side, will cause unequal sorption

of

moisture, increasing the likelihood of wood cup-

ping.

3.1

Natural Weathering

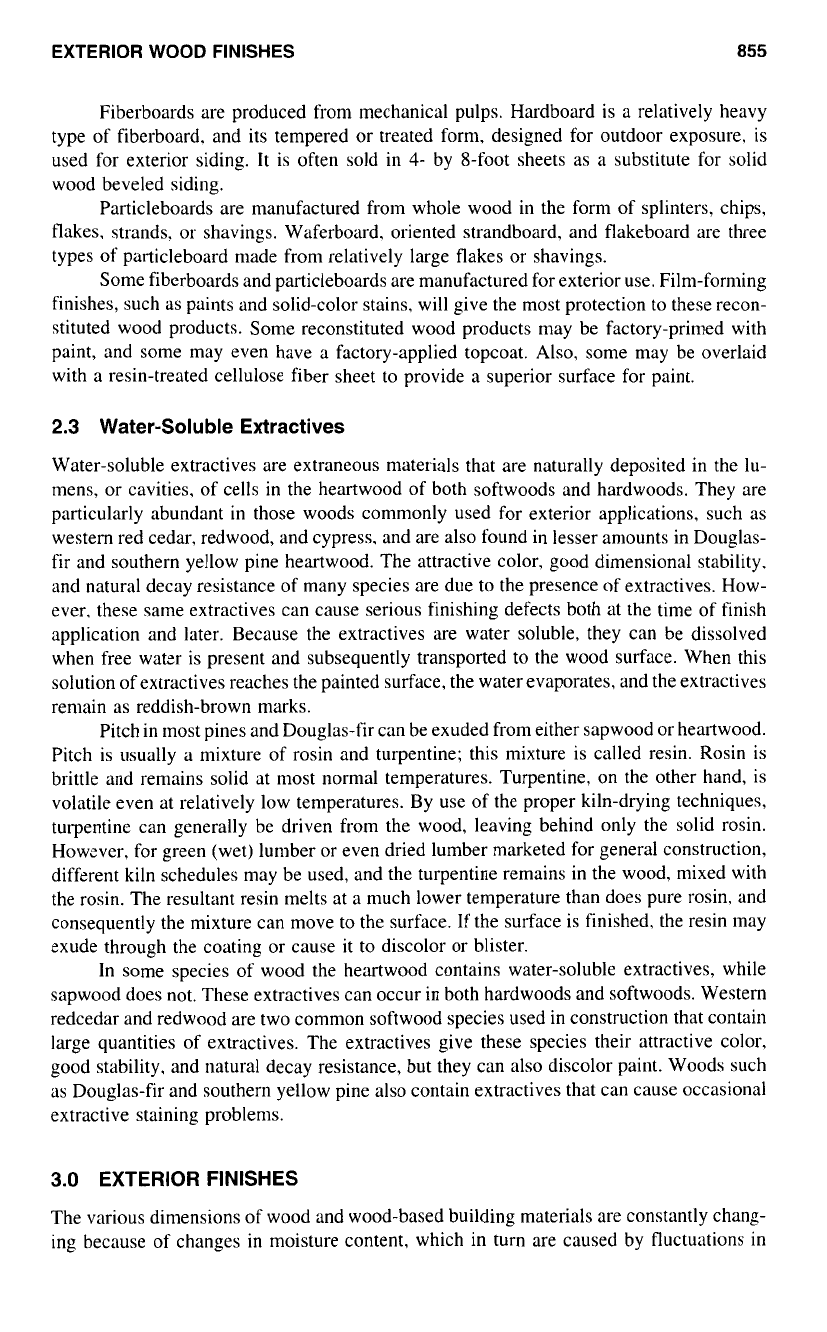

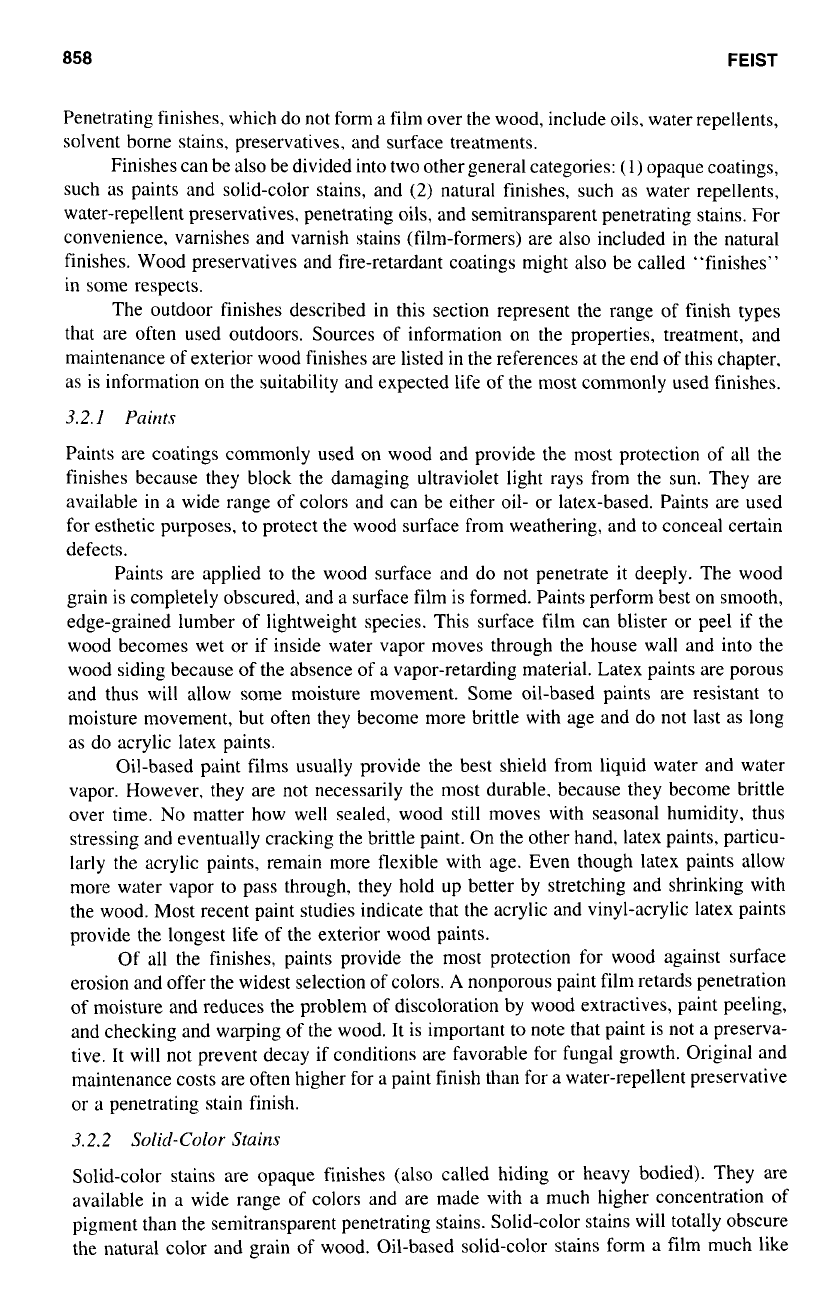

The simplest finish for wood is created by the natural weathering process. Without paint

or treatment of any kind, wood surfaces gradually change

in

color and texture and then

stay almost unaltered for

a

long time if the wood does not decay. Generally, the dark-

colored woods become lighter and the light-colored woods become darker. As weathering

continues. all woods become gray, accompanied by photodegradation and gradual loss of

wood cells at the surface. As a result, exposed unfinished wood will slowly wear away

in a process called erosion (Fig.

4).

The weathering process is

a

surface phenomenon and is

so

slow that most softwoods

erode at

an

average rate of about

!l4

inch per century. Dense hardwoods erode at

a

rate

of

only

!l8

inch per century. Very low density softwoods, such as western redcedar. may

erode at

a

rate as high

as

v'-

inch per century. In cold northern climates, erosion rates as

low

as

!+

inch per century have been reported.

EXTERIOR WOOD

FINISHES

857

Figure

4

The weathering process

of

round and square timbers. Cutaway shows that interior wood

below the surface is relatively unchanged, even though surface wood

is

weathered and eroded.

The physical loss of wood substance from the wood surface (erosion) during weather-

ing depends not only on wood species and density, but also on growth rate, ring orientation,

amount of irradiation, rain action, wind, and degree of exposure. Erosion also occurs most

rapidly in thin-walled fibers of earlywood in softwoods and, at a slower rate, in dense

latewood. Accompanying this loss of wood substance are the swelling and shrinking

stresses caused by fluctuations in moisture content. All this results in surface roughening,

grain raising, differential swelling of earlywood and latewood bands, and the formation

of many small parallel checks and cracks. Larger and deeper cracks may also develop,

and warping frequently occurs (Fig.

4).

The weathering process is usually accompanied by the growth of dark-colored spores

and mycelia of fungi

or

mildew on the surface, which gives the wood a dark gray, uneven,

and unsightly appearance. In addition, highly colored wood extractives in such species as

western redcedar and redwood add to the variable color of weathered wood. The dark

brown color of extractives may persist for a long time in areas not exposed to the sun and

where the extractives are not removed by the washing action of rain.

3.2

Applied Finishes

Finishes

or

coatings are applied to exterior wood surfaces for a variety of reasons. The

particular reason will determine the type of finish selected and subsequently the amount

of protection provided to the wood surface as well as the life expectancy for the finish.

Two basic types of finishes

(or

treatments) are used to protect wood surfaces during

outdoor weathering:

(1)

those that form a film, layer,

or

coating on the wood surface (film-

forming) and

(2)

those that penetrate the wood surface, leaving no distinct layer

or

coating

(non-film-forming). Film-forming finishes include paints of all descriptions, varnishes,

varnish stains, and solid-color stains as well as overlays bonded to the wood surface.

858

FEET

Penetrating finishes, which do not form

a

film over the wood, include oils, water repellents,

solvent borne stains, preservatives, and surface treatments.

Finishes can be also be divided into two other general categories:

(1)

opaque coatings,

such

as

paints and solid-color stains, and

(2)

natural finishes, such

as

water repellents,

water-repellent preservatives, penetrating oils, and semitransparent penetrating stains. For

convenience, varnishes and varnish stains (film-formers) are also included in the natural

finishes. Wood preservatives and fire-retardant coatings might

also

be called “finishes”

in some respects.

The outdoor finishes described

in

this section represent the range of finish types

that are often used outdoors. Sources of information on the properties, treatment, and

maintenance of exterior wood finishes are listed in the references at the end of this chapter.

as

is information on the suitability and expected life of the most commonly used finishes.

3.2.1

Paints

Paints are coatings commonly used

on

wood and provide the most protection of all the

finishes because they block the damaging ultraviolet light rays from the sun. They are

available in a wide range

of

colors and can be either oil- or latex-based. Paints are used

for esthetic purposes, to protect the wood surface from weathering, and to conceal certain

defects.

Paints are applied to the wood surface and do not penetrate it deeply. The wood

grain is completely obscured, and a surface film is formed. Paints perform best on smooth,

edge-grained lumber of lightweight species. This surface film can blister or peel if the

wood becomes wet or if inside water vapor moves through the house wall and into the

wood siding because of the absence of a vapor-retarding material. Latex paints are porous

and thus will allow some moisture movement. Some oil-based paints are resistant to

moisture movement, but often they become more brittle with age and do not last

as

long

as do acrylic latex paints.

Oil-based paint films usually provide the best shield from liquid water and water

vapor. However, they are not necessarily the most durable, because they become brittle

over time.

No

matter how well sealed, wood still moves with seasonal humidity, thus

stressing and eventually cracking the brittle paint. On the other hand. latex paints, particu-

larly the acrylic paints, remain more flexible with age. Even though latex paints allow

more

water vapor

to

pass through, they hold up better by stretching and shrinking with

the wood. Most recent paint studies indicate that the acrylic and vinyl-acrylic latex paints

provide the longest life of the exterior wood paints.

Of all the finishes, paints provide the most protection for wood against surface

erosion and offer the widest selection

of

colors.

A

nonporous paint film retards penetration

of moisture and reduces the problem of discoloration by wood extractives, paint peeling,

and checking and warping of the wood. It is important

to

note that paint is not

a

preserva-

tive. It will not prevent decay if conditions are favorable for fungal growth. Original and

maintenance costs are often higher for

a

paint finish than for

a

water-repellent preservative

or

a

penetrating stain finish.

3.2.2

Solicl-Color Stains

Solid-color stains are opaque finishes

(also

called hiding or heavy bodied). They are

available in

a

wide range of colors and are made with a much higher concentration

of

pigment than the semitransparent penetrating stains. Solid-color stains will totally obscure

the natural color and grain

of

wood. Oil-based solid-color stains form

a

film much like

EXTERIOR

WOOD

FINISHES 859

paint and as a result can peel loose from the substrate. Latex-based solid-color stains are

also

available and form

a

film.

as

do the oil-based solid-color stains. Both these stains

are similar to thinned paints and can usually be applied over old paint or stains if the old

finish is securely bonded to the wood.

3.2.3

Senlitransl~a~e~lt

Penetrating Stclirls

Semitransparent penetrating stains are only moderately pigmented and thus do not totally

hide the wood grain. These stains penetrate the wood surface to

a

degree, are porous

to

water vapor, and do not form a surface film like paints. As

a

result, they will not blister

or peel even

if

moisture moves through the wood. Penetrating stains are alkyd- or oil-

based, and some may contain

a

fungicide (preservative or mildewcide) as well

as

a

water

repellent. Moderately pigmented latex-based (waterborne) stains are also available, but

they do not penetrate the wood surface as do the oil-based stains.

The semitransparent stains are most effective on rough lumber. weathered lumber.

or rough-sawn plywood surfaces. but they also provide satisfactory performance on smooth

surfaces. They are available in

a

variety of colors and are especially popular in the brown

or red earth tones because they give a natural or rustic appearance. They are an excellent

finish for weathered wood. Semitransparent penetrating, oil-based stains are not effective

when applied over a solid-color stain or over old paint. They are not recommended for

use on hardboard and oriented strandboard.

An effective stain of the semitransparent penetrating type is the Forest Products

Laboratory natural finish developed in the

1950s.

This finish has a linseed oil vehicle.

a

fungicide to protect the

oil

and wood from mildew, and

a

water repellent that protects the

wood from an excessive penetration of water. It is available in durable red and brown

iron oxide pigments that simulate the natural colors of redwood and cedar. A variety

of

other colors can

also

be achieved with this finish.

3.2.4 Water-Repellent Preservati\~e.s

and

Water Repellents

A water-repellent preservative may be used as

a

natural finish. It contains

a

fungicide or

mildewcide (the preservative),

a

small amount of wax for water repellency, a resin or

drying oil. and a solvent. such as turpentine or mineral spirits. Water-repellent preservatives

do not contain coloring pigments. Therefore the resulting finish will vary in color depend-

ing upon the species of wood. The mildewcide also prevents wood from darkening

(graying).

The initial application of the water-repellent preservative to smooth wood surfaces

is usually short-lived. During the first few years, the finish may have to be applied every

year. After the wood has gradually weathered to

a

uniform color, the treatments are more

durable and the wood needs refinishing only when the surface starts to become unevenly

colored by fungi.

Inorganic pigments can be added to the water-repellent preservative solutions

to

provide special color effects, and the mixture is then similar to the semitransparent pig-

mented penetrating stains. Colors that match the natural color of the wood and extractives

are usually preferred.

As

with semitransparent stains, the addition of pigment to the finish

helps stabilize the color and increase the durability of the finish.

Some water-repellent preservatives may also be used

as

a

treatment for bare wood

before priming and painting or

in

areas where old paint has peeled, exposing bare wood,

particularly around butt joints or in comers. This treatment keeps rain or dew from penetrat-

ing into the wood, especially at joints and end grain, and thus decreases the shrinking and

860

FEET

swelling

of

wood. As a result. less stress is placed on the paint film, and its service life

is extended. This stability is achieved by the small amount

of

wax present in water-

repellent preservatives. The wax decreases the capillary movement or wicking of water

up the back side

of

lap or drop siding. The fungicide inhibits surface decay. Water-repellent

preservatives are also used as edge treatments for panel products like plywood.

Water repellents are also available. These are water-repellent preservatives with the

fungicide, mildewcide, or preservative left out. Water repellents are

not

effective natural

finishes by themselves but can be used as a stabilizing treatment before priming and

painting.

3.2.5

Oils

and

Vurnishes

Many oil or oil-based natural wood finish formulations are available for finishing exterior

wood. The most common oils are linseed and tung. However, these oils may serve as a

food source for mildew

if

applied

to

wood in the absence of a mildewcide. The oils will

also perform better if a water repellent and a UV stabilizer are included in the formulation.

Alkyd resin and related resin commercial formulas are also available.

All

these oil systems

will protect wood exposed outdoors, but their average lifetime may be only as long as

that described for the water-repellent preservatives.

Clear coatings of conventional spar or marine varnishes, which are film-forming

finishes, are not generally recommended for exterior use on wood. Shellac or lacquers

should never be used outdoors because they are very sensitive

to

water and are very brittle.

Varnish coatings become brittle by exposure to sunlight and develop severe cracking and

peeling, often

in

less than

2

years. Refinishing will often involve removing all the old

varnish. Areas that are protected from direct sunlight by overhang or are on the north side

of

the structure can be finished with exterior-grade varnishes. Even in protected areas.

a

minimum

of

three coats of varnish is recommended, and the wood should be treated with

a water-repellent preservative before finishing. Using compatible pigmented stains and

sealers as undercoats will also contribute to a greater service life

of

the clear varnish

finish. In marine exposures, six coats of varnish should be applied for best performance.

4.0

SUMMARY

Wood continues to play an important role as a structural material in today’s high-tech

society. As lumber and

in

reconstituted products, wood is commonly used for house siding,

trim, decks, fences, and countless other exterior and interior applications. When wood is

exposed to the elements. particularly sunlight and moisture, special precautions must be

taken in structural design as well as in the selection and application of the finish.

This report described the characteristics of exterior wood finishes and their proper

application to solid and reconstituted wood products. It described how manufacturing and

construction practices affect the surfaces of wood products, how various types of finishes

interact with the surface, and how weathering affects the finished surfaces. Methods for

selecting various exterior wood finishes were presented.

REFERENCES

I.

D.

L.

Cnsscns and

W.

C.

Feist, Exterior wood in the South: Selcction, applications and finishes,

USDA

Forest Service Forest Products Laboratory. General Technical Report FPL-GTR-69.

Madison,

WI:

Forest Products Laboratory, 1991.

EXTERIOR WOOD

FINISHES 861

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

IO.

11.

12.

13.

14.

IS.

16.

D. L. Cassens, B. R. Johnson, W. C. Feist. and R. C. De Groot. Selection and use of preservative

treated wood. Publication No. 7299. Madison, WI: Forest Products Society, 1995.

W. C. Feist, Weathering of wood in structural uscs, in

Structrcrrrl

Use

of Wood

in

Adverse

Envirorvrterl/.s

(R.

W. Meyer and

R.

M. Kellogg, eds.). New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold,

W. C. Feist, Finishing wood for exterior use,

in

Fir~ishir~g

Eastern

H~trc/n~ood.s

(R. M. Carter,

ed.). Madison, WI: Forest Products Research Society, 1983, pp. 185-198.

W. C. Feist, Outdoor wood weathering and protection, in

Archcreologicd

Wood,

Properties.

C/lerrlisr,y

NII~

Presenutiorl

(R. Rowell, ed.). Advances

in

Chemistry Series,

No.

225. Wash-

ington, DC: American Chemical Society, 1990, pp. 263-298.

W. C. Feist, Painting and finishing exterior wood,

J.

Coatings

Tech..

68(856), 23-26 (1996).

W. C. Feist, Finishing exterior wood, Federation Serles on Coatings Technology. Bluc Bell,

PA: Federation of Societies for Coatings Technology, 1996.

W. C. Feist, The challenges of selecting finishes

for

exterior wood,

Forest

Products

J..

47(5),

16-20 (1997).

W. C. Feist and D. N.-S. Hon, Chemistry of Weathering and Protection, in

The

C/lerni.stt>>

Solid

Wood

(R. M. Rowell, ed.). ACS Advances in Chemistry Series

No.

207. Washington,

DC.: American Chemical Society, 1984, pp. 401-454.

Forest Products Laboratory,

Wood

Hmdbook:

Wood

NS

mt

Gtgir~wir~g

Mrrtericd.

Agricultural

Handbook

No.

72 (revised). Madison, WI: U.S. Department of Agriculture, 1987.

T. M. Gorman and W. C. Feist, Chronicle of

65

years of wood finishing research at the Forest

Products Laboratory. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report FPL-GTR-60. Madison,

WI: Forest Products Laboratory, 1989.

F. W. Kropf,

J.

Sell, and W. C. Feist, Comparative weathering tests of North American and

European exterior wood finishes,

Forest

Prodtccts

J.,

44(

IO),

33-41 (1994).

K.

A. McDonald, R. H. Falk, R.

S.

Williams. and J. E. Winandy, Wood decks: Materials,

construction, and finishing, Publication No. 7298. Madison, WI: Forest Products Society, 1996.

R.

S.

Williams, M. T. Knaebe, and W. C. Feist, Finishcs for exterior wood: Sclection, applica-

tlon. and maintenance, Publication No. 7291. Madison, WI: Forest Products Society, 1996.

R.

S.

Williams, Effects

of

acidic depositlon on painted wood, in

Acidic

Deposition:

Sttrte

of’

Science

and

Tec/~nolo,~p.

Effects of Acidic Deposition on Materials Report

19,

National Acid

Precipitation Assessment Program. Vol. 3, Section 4, 1991, pp. 19-165 to 19-202.

R.

S.

Williams, Effects of acidic deposition on paintcd wood:

A

revlew,

J.

Cocrtings

Tech.,

1982, pp. 156-178.

63(800),

53-73 (1991).