Russ J.C. Image Analysis of Food Microstructure

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

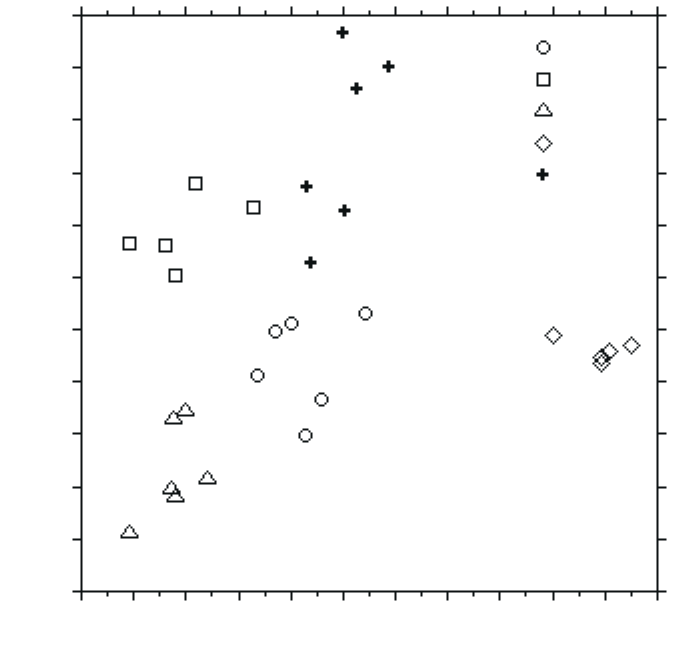

FIGURE 5.54 Two-parameter plot of inscribed radius and radius ratio (inscribed/circum-

scribed) separates the five nut classes.

.35 .4 .45 .5 .55 .6 .65 .7 .75 .8 .85 .9

Radius_Ratio

.45

.5

.55

.6

.65

.7

.75

.8

.85

.9

.95

1

Inscrib.Rad.(cm)

almond

brazil

cashew

filbert

walnut

2241_C05.fm Page 357 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

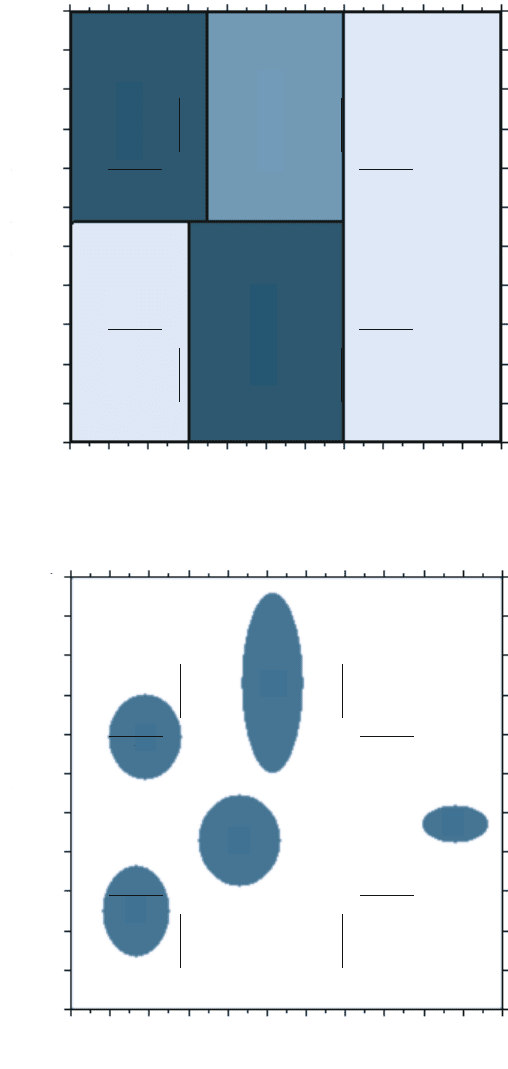

FIGURE 5.55 Parameter ranges that classify the five nut types.

FIGURE 5.56 Nut classes described by mean and standard deviation.

.35 .4 .45 .5 .55 .6 .65 .7 .75 .8 .85 .9

Radius Ratio

Inscribed Radius

.45

.5

.55

.6

.65

.7

.75

.8

.85

.9

.95

1

Brazil

Cashew

Almond

Walnut

Filbert

.35 .4 .45 .5 .55 .6 .65 .7 .75 .8 .85 .9

Radius Ratio

Inscribed Radius

.45

.5

.55

.6

.65

.7

.75

.8

.85

.9

.95

1

A

B

C

W

F

2241_C05.fm Page 358 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

CONCLUSIONS

In addition to the stereological measurement of structure, described in Chapter

1, there is often interest in the individual features present in an image. Counting the

features present must take into account the effects of a finite image size, and deal

with the features that are intersected by the edges. Additional edge corrections are

needed when feature measurements are performed.

Feature measurements can be grouped into measures of size, shape, position

(either absolute or relative to other features present) and color or density values

based on the pixel values recorded. Calibration of the image dimensions and intensity

values are usually based on measurement of known standards and depend on the

stability and reproducibility of the system.

The variety of possible measures of size, shape, and position results in a large

number of measurement parameters which software can measure. The algorithms

used vary in accuracy, but a greater concern is the problem of deciding which

parameters are useful in each application. That decision must rely on the user’s

independent knowledge of the specimens, their preparation, and the imaging tech-

niques used.

Interpretation of measured data often makes use of descriptive statistics such as

mean and standard deviation, histogram plots showing the distribution of measured

values, and regression plots that relate one measurement to another. Comparisons

of different populations generally require nonparametric procedures if the measured

values are not normally distributed. Classification (feature identification) is also a

statistical process, which usually depends on the measurement of representative

training sets from each population.

2241_C05.fm Page 359 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC