Russ J.C. Image Analysis of Food Microstructure

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The trend in the plot shows an increase in mean value, but it may be that the increase

in variation (e.g., standard deviation) with depth is actually more meaningful.

As an indication of the difficulty of visually perceiving the important variable(s)

involved in these textural gradients, Figure 5.42 shows another fruit cross-section

(a different variety). There is enough complexity in the structure to make it appear

visually similar to the first one. Seeing “through” the complexity to discern whatever

underlying differences are present is very difficult.

(a)

(b) (c)

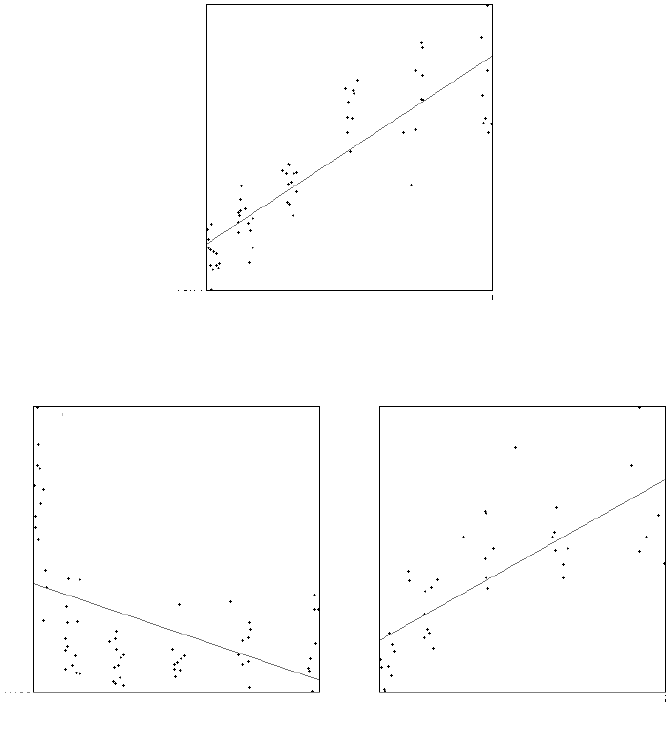

FIGURE 5.40 Plots of cell size (a) and shape (b) vs. depth, and plot of the size of intercellular

air spaces (c) vs. depth.

43.89

13.77

Equivalent Circular Diameter

min=94.71 Centroid Depth max=229.09

Equation: Y = 0.14767 * X + 4.79690

R-squared = 0.87510, 64 points

Cell size vs. depth

3.277

1.186

Equivalent Circular Diameter

min=94.71 Centroid Depth max=229.09

Equation: Y = -0.00530 * X + 2.48801

R-squared = 0.47595, 64 points

Cell Aspect Ratio vs. depth

32.07

6.18

Equivalent Circular Diameter

min=14.76 Centroid Depth max=135.15

Equation: Y = 0.12104 * X + 9.15184

R-squared = 0.76306, 40 points

Size of intercellular space vs. depth

2241_C05.fm Page 337 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

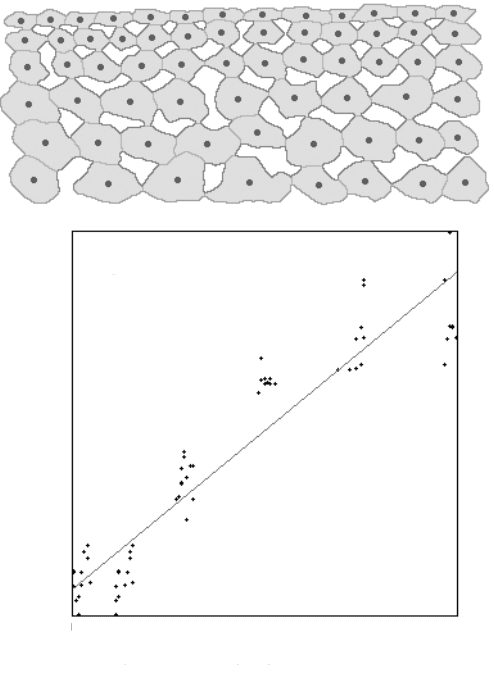

When measurements similar to those above are performed different results are

observed. The trends of size and nearest neighbor spacing are even more pronounced

than in the first sample, but there is only a weak shape variation with depth. Area

fraction is still not correlated with depth, but the fraction of cell wall perimeter that

is adjacent to another cell, rather than adjacent to air space, does show a trend in

the first few layers near the surface.

These examples emphasize that many different kinds of information are available

from image measurement. Generally, these fit into the categories of global measure-

ments such as area fraction or total surface area, or feature-specific values such as

(a)

FIGURE 5.41 Plots of nearest neighbor distance vs. depth: (a) for cells; (b) for air spaces.

39.458

13.038

Nearest Neighbor Distance

min=8

Depth

max=142

Equation: Y = 0.16277 * X + 13.6790

R-squared = 0.94268, 64 points

Center-to-center nearest

neighbor distance vs. depth

2241_C05.fm Page 338 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

the size, shape and position of each cell. Selecting which to measure, and relating

the meaning of that measurement back to the structure represented in the image,

requires thinking about the relationships between structural properties revealed in a

cross-sectional image and the relevant mechanical, sensory or other properties of

the fruit. Selection benefits from a careful examination of images to determine what

key variations in structure are revealed in the images. These may involve gradients

as a function of depth, which may be related to sensory differences between varietals

or as a function of storage conditions.

(b)

FIGURE 5.41 (continued)

37.215

9.8848

Nearest Neighbor Distance

min=14

Depth

max=135

Equation: Y = 0.08527 * X + 15.5357

R-squared = 0.43035, 56 points

Nearest Neighbor Distances

between ultimate eroded

points of air spaces vs.

depth

2241_C05.fm Page 339 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

(a)

(b)

(c)

FIGURE 5.42 Measurement of the cross-section of a different fruit variety: (a) thresholded

binary; (b) cells and air spaces with skeletonized boundaries identified as adjacent to another

cell or adjacent to air space; (c) plot of area fraction vs. depth; (d) plot of fraction of the cell

walls that are adjacent to another cell; (e) plot of cell size vs. depth; (f) plot of cell shape

(aspect ratio) vs. depth; (g) plot of center-to-center cell nearest neighbor distance vs. depth.

0.65

0.7

0.75

0.8

0.85

0.9

0.95

Area %

Area fraction vs. depth

2241_C05.fm Page 340 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

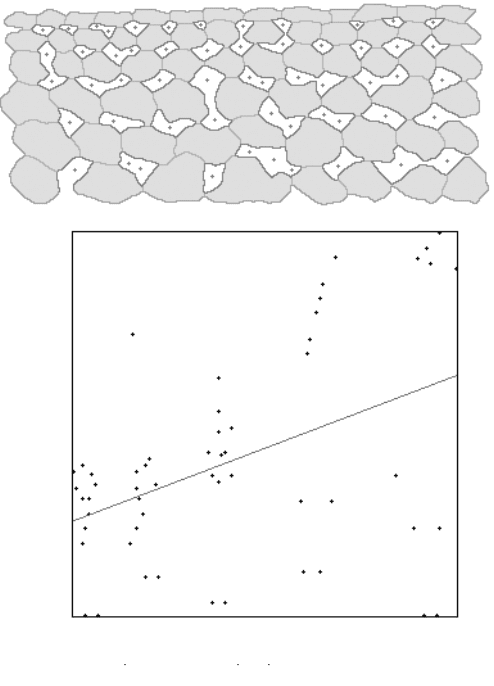

(d)

(e)

(f) (g)

FIGURE 5.42 (continued)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

% Adjacent

Fraction of adjacent boundaries vs. depth

60.50

14.22

Equivalent Circular Diameter

min=104.06 Depth max=237.69

Equation: Y = 0.32298 * X + -16.9126

R-squared = 0.95297, 60 points

Cell Size vs. Depth

4.07

1.19

Aspect Ratio

min=104.06 Depth max=237.69

Equation: Y = -0.00574 * X + 2.85826

R-squared = 0.41267, 60 points

Cell Shape vs. Depth

50.79

12.61

Nearest Neighbor Distance

min=104.06 Depth max=237.69

Equation: Y = 0.23027 * X + 11.4818

R-squared = 0.91707, 60 points

Cell Nearest Neighbor Distance

vs. Depth

2241_C05.fm Page 341 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

SHAPE

In the preceding example, one of the parameters that varied with depth was the

aspect ratio of the cells. That is one of many parameters that can be used to describe

shape, in this case representing the ratio of the maximum caliper dimension to the

minimum caliper dimension. That is not the only definition of aspect ratio that is

used. Some software packages fit a smooth ellipse to the feature and use the aspect

ratio of the ellipse. Others measure the longest dimension and then the projected

width perpendicular to that direction. Each of these definitions produces different

numeric values. So even for a relatively simple shape parameter with a familiar-

sounding name, like aspect ratio, there can be several different numeric values

obtained. Shape is one of the four categories (along with size, color or density, and

position) that can be used to measure and describe features, but shape is not some-

thing that is easily translated into human judgment, experience or description.

There are very few common adjectives in human language that describe shape.

Generally we use nouns, and say that something is “shaped like a …,” referring to

some archetypical object for which we expect the other person to have the same

mental image as ourselves. One of the few unambiguous shapes is a circle, and so

the adjective round really means shaped like a circle. But while we can all agree on

the shape of a circle, how can we put numbers on the extent to which something is

shaped like (or departs from the shape of) a circle? Figure 5.43 illustrates two ways

that an object can depart from circularity, one by elongating in one direction (become

more like an ellipse), and the other by remaining equiaxed but having an uneven

edge. There are more possibilities than that, of course — just consider n-sided regular

polygons as approximations to a circle.

FIGURE 5.43 Two ways to vary from being like a circle.

2241_C05.fm Page 342 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

The departure from roundness that produces an uneven edge is often measured

by a parameter called the formfactor, which is calculated from the area and perimeter,

as summarized in Table 5.1. The departure that produces elongation is often mea-

sured by either the aspect ratio, or by a parameter usually called roundness. Actually,

neither of these names (nor any of the others in Table 5.1) is universal. Other names

like circularity, elongation, or compactness are used, and sometimes the equations

are altered (e.g., inverted, or constants like π omitted), in various computer packages.

The problem, of course, is that the names are arbitrary inventions for abstract

arithmetic calculations.

Each of the formulas in Table 5.1 extracts some characteristic of shape, and each

one is formally dimensionless so that, except for its effect on measurement precision,

the size of the object does not matter. An almost unlimited number of these derived

shape parameters can be constructed by combining the various size parameters so

that the dimensions and units cancel out. Some of these derived parameters have

been in use in a particular application field for a long time, and so have become

familiar to a few people, but none of them corresponds very well to what people

mean by shape.

Figure 5.44 shows a typical application in which a shape parameter (form factor

in the example) is used. The powder sample contains features that vary widely in

TABLE 5.1

Derived Shape Parameters

Parameter name Calculation

Formfactor

Roundness

Aspect Ratio

Elongation

Curl

Convexity

Solidity

Hole Fraction

Radius Ratio

4

2

π⋅Area

Perimeter

4

2

⋅

⋅

Area

MaxDimπ

MaxDimension

MinDimension

FiberLength

FiberWidth

Length

FiberLength

ConvexPerim

Perimeter

Area

ConvexArea

FilledArea NetArea

FilledArea

−

InscribedDiam

CircumscribedDiam

2241_C05.fm Page 343 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

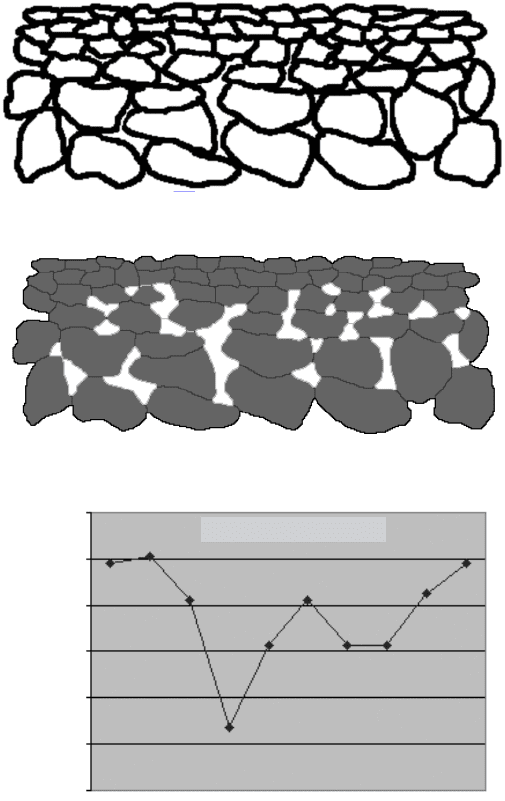

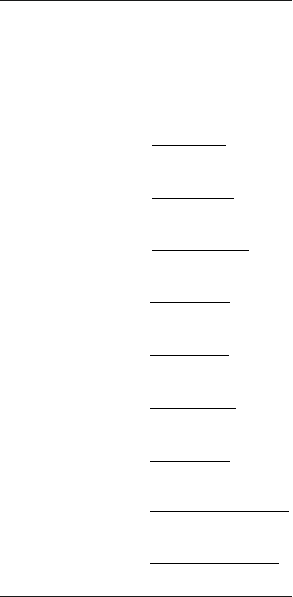

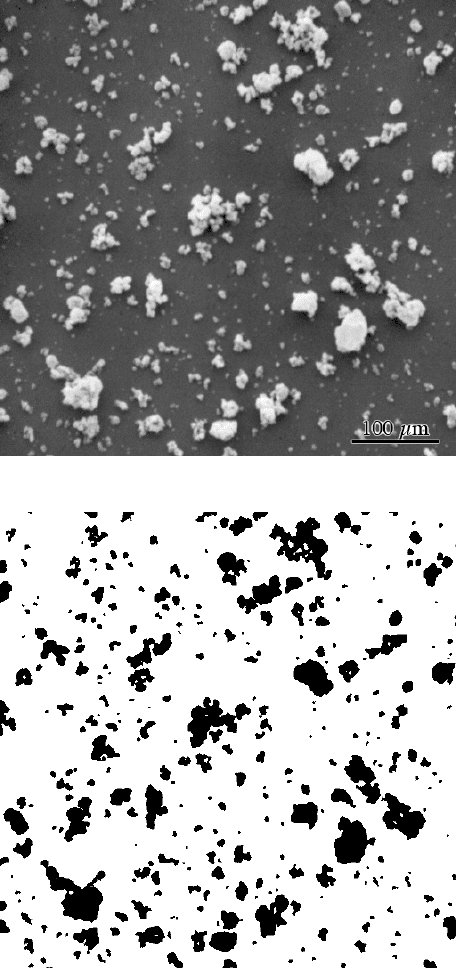

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 5.44 Shape and size of powder sample: (a) original SEM image; (b) thresholded;

(c) size distribution (equivalent circular diameter); (d) shape distribution (formfactor); (e)

regression plot of shape vs. size.

2241_C05.fm Page 344 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

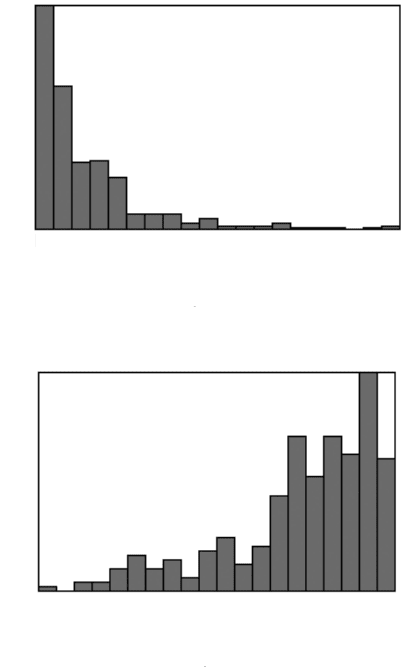

size and shape. Histograms of the size and shape indicate that there are many small

particles and many that are nearly round (a formfactor of 1.0 corresponds to a perfect

circle). By plotting the size vs. the shape for each particle in the image, a statistically

very significant trend is observed: the small particles are fairly round but the large

ones are not. A common cause for that behavior (and the specific cause in this case)

is agglomeration. The large particles are made up from many adhering small ones.

There are many other types of shape change with size, in fact it is unusual for objects

to vary over a wide size range without some accompanying shape variation.

Regression plots, such as the one in Figure 5.40, make the implicit assumption

that the relationship between the two variables is linear. Nonlinear regression can

also be performed, but still assumes some functional form for the relationship. A

nonparametric approach to determining whether there is a statistically significant

correlation between two variables is the Spearman approach, which plots the rank

(c)

(d)

FIGURE 5.44 (continued)

0

102

Count

Min = 2.52 Equiv.Diam.(µm) Max = 52.17

Total=301, 20 bins

Mean = 10.0938, Std. Dev.=9.16040

Skew = 2.24485, Kurtosis = 8.554109

0

49

Count

Min = 0.121 Formfactor Max = 0.922

Total=301, 20 bins

Mean = 0.70873, Std. Dev.=0.17147

Skew = -1.09979, Kurtosis = 3.58339

2241_C05.fm Page 345 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC

order of the measured values rather than the values themselves. Of course, finding

that there is a correlation present does not address the question of why.

One problem with the dimensionless derived shape parameters is that they are

not very specific. Another is that they do not correspond in most cases to what

humans mean when they say that features have similar or dissimilar shapes. As an

example, all of the features in Figure 5.45 were drawn to have the same formfactor,

yet to a human observer they are all extremely different shapes.

There are two other ways to describe some of the characteristics of shape that

do seem to correspond to what people see. One of these deals with the topology of

features, and those characteristics efficiently extracted by the feature skeleton. The

second is the fractal dimension of the feature boundary. These are in some respects

complementary, because the first one ignores the boundary of the feature to concen-

trate on the gross aspects of topological shape while the second one ignores the

overall shape and concentrates on the roughness of the boundary.

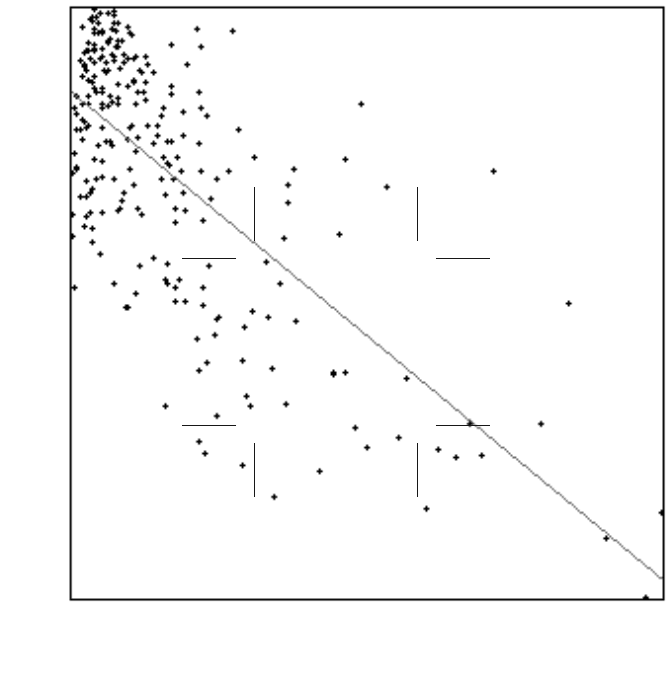

(e)

FIGURE 5.44 (continued)

0.121

0.922

Formfactor

min = 2.52

Equivalent Circular Diameter (µm)

max = 52.17

Equation: Y = -0.01330 *X + 0.84334

R-squared = 0.69136, 288 points

2241_C05.fm Page 346 Thursday, April 28, 2005 10:30 AM

Copyright © 2005 CRC Press LLC