Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

43.2 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

rather than helps the work of understanding the past and pursuing social justice in the present.”

Effective design solutions, responding to the full spectrum of personal and environmental factors,

must reinforce this new definition of (dis)ability. As such, the P-E fit model also proposes more

expansive definitions and roles of design and medicine.

43.2 PERSON-ENVIRONMENT FIT

“Fit” is a concept familiar in clothing. Consider the perfect pair of jeans: size, color, style, and cost

are just a few of the most relevant factors. The search for perfect jeans is often a lifelong pursuit

(Reda, 2006). Achieving perfect fit in a home or community can be equally elusive.

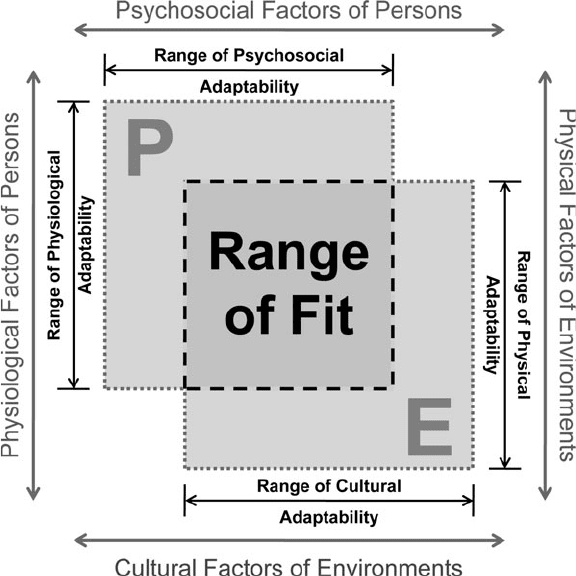

The concept of person-environment fit was developed with regard to people and their occupations

and vocations, and it has been applied to a variety of contexts (Caplan et al., 1974). Fit is simply the

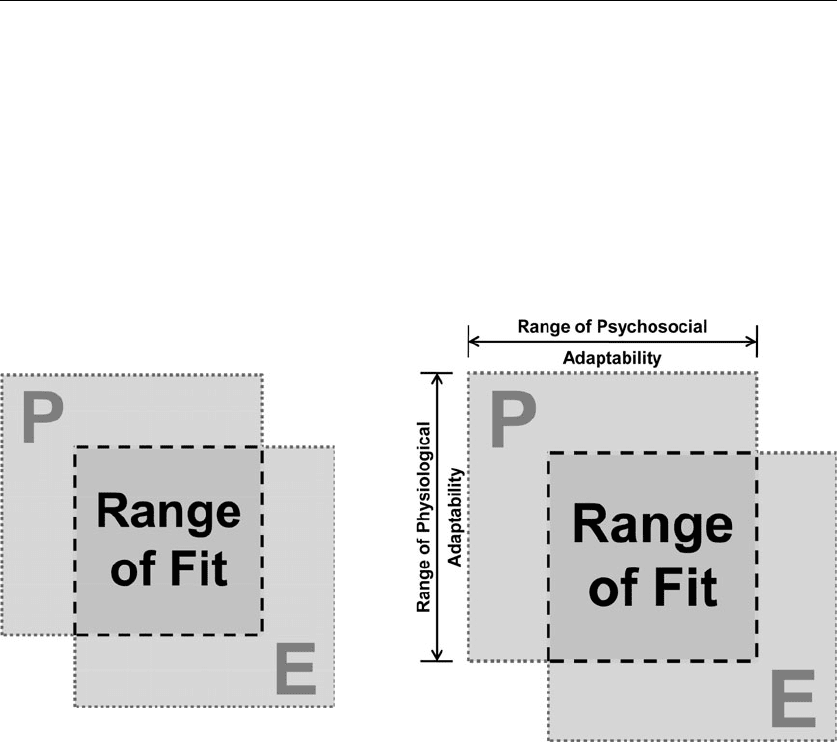

correspondence between two distinct elements, person and environment in this case (see Fig. 43.1). Fit

is the central component of the model, illustrated in Fig. 43.1 as the overlap of person and environment.

P-E fit exists on a continuum from complete lack of fit to optimal fit. The extremes, however, rarely

occur. Instead, some degree of correspondence as well as incongruity is usually present, necessitating

changes to aspects of the person and/or aspects of the environment (Lawton and Nahemow, 1973).

In the model, P represents a unique set of characteristics inherent to the individual, including

both physiological and psychosocial aspects (see Fig. 43.2). Physical characteristics include biologi-

cal health, sensory and motor skills, and cognitive ability, many of which can be objectively listed

FIGURE 43.1 The range of fit model illustrates fit as

the convergence of the person’s and the environment’s

attributes.

Long description: Figure 43.1 illustrates range of fit as

a function of personal and environmental factors. The

person is represented by a square labeled P. The environ-

ment is represented by a similar square labeled E. The

boundaries of both squares are dotted to illustrate they

are permeable and dynamic. In a diagonal arrangement,

the two squares overlap to form a third square, labeled

range of fit. Range of fit is the degree of congruence

between the person and the environment.

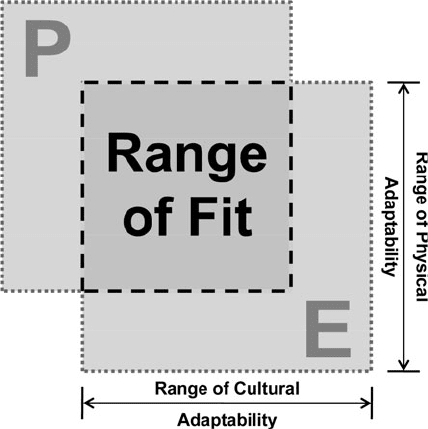

FIGURE 43.2 The second step in the creation of the range of fit

model illustrates the additional components of a person’s psychosocial

and physiological attributes.

Long description: Figure 43.2 illustrates two attributes of the person

P in the range of fit model: physiological attributes and psychosocial

attributes. The vertical dimension is labeled range of physiological

adaptability, and the horizontal dimension of the square is labeled

range of psychosocial adaptability. Along each of these edges, there is

a line with arrows at each end. The arrows hit barriers, suggesting that

there is a finite range of adaptability for each person.

REDEFINING DESIGN AND DISABILITY: A PERSON-ENVIRONMENT FIT MODEL 43.3

and quantitatively measured. Height, gender, pulmonary function, aural acuity, tactile sensitivity,

long- and short-term memory, and presence of disease are a few factors (World Health Organization,

1980, 2001). Additionally, the psychosocial domain includes behaviors, emotions, world view, and

self-concept. For example, these aspects are influenced by perception, religious beliefs, mores, and

self-efficacy (Altman and Chemer, 1984).

More accurately, a person is defined through the interaction of all these factors rather than by an

independent list of variables. For example, a person who has diabetes can experience serious, long-

term consequences of the disease including heart and kidney damage, vision impairment, or damage

to the vascular system. If this individual values good health, he or she will be motivated to control

diet, exercise regularly, and take medications. If health and well-being are not a priority, disease

outcomes can be severe. Additionally, poor health resulting from diabetes can negatively impact, by

reducing the range of functioning, the individual’s adaptability. Fit, however, is also influenced by

the environment.

Like the person (P) side of the model, the environment (E) can be divided into two realms: the

physical environment and the cultural environment (see Fig. 43.3). Natural environments (e.g.,

topography, climate, and flora) and constructed environments (e.g., transportation, sidewalks, and

buildings) comprise the physical realm. Equally significant is the cultural environment, comprised of

shared values and mores, political and legal codes, and cultural definitions and hierarchies (Altman

and Chemer, 1984). Cultural environments include family and household structure, community ide-

als, and social and health care programs (World Health Organization, 1980).

As with people, environments are not defined solely by individual variables but also by their

interactions, the interface between physical and cultural facets. Ed Roberts and his determination to

FIGURE 43.3 The third step in the creation of the range of fit model

illustrates the additional components of an environment’s cultural and

physiological attributes.

Long description: Figure 43.3 illustrates two attributes of the environ-

ment E in the range of fit model: physiological attributes and cultural

attributes. Range of physiological adaptability is represented vertically,

and range of cultural adaptability is represented horizontally. Both

edges are illustrated with a line with arrows at each end. The line, at

each end, hits a barrier, suggesting that there is a finite range of adapt-

ability for each person.

43.4 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

change the University of California, Berkeley, campus is a good example. A single person facilitated

his use of the campus hospital as a dormitory. Combined with the financial resources to pay personal

attendants, Ed changed attitudes of campus administrators, faculty members, and students. In six

years, the hospital-turned-dormitory became a formalized program, and the city of Berkeley commit-

ted $50,000 to improve sidewalks. Likewise, students facilitated physical changes in the environment

by changing values in the cultural environment (Shapiro, 1994).

43.3 THE DYNAMICS OF FIT

It is important to place all these examples in a larger context. Completing the 100-m dash, e.g., can

vary from the world record holder requiring a few seconds to the individual who needs hours. Just as

important as the total range of variability between people is the variability experienced by each individ-

ual. While a sprinter runs faster in a particular race, there is a range of time associated with everyone’s

day-to-day performance. A poor night’s sleep, mental distraction, or temporary change in health status

can alter performance. Arthritis can be influenced by temperature or time of day. Chronic illnesses can

be long-lasting or cyclical, thereby influencing human functioning on highly variable schedules. For

some individuals, functioning can be relatively static with incremental changes over time. For others,

changes in functioning could be sudden and extreme. Judy Heumann coined the phrase “temporar-

ily able-bodied,” a concept suggesting that no person is or will be without a disabling condition in

his or her life span (Rae, 1989). Temporary conditions include the aftereffects of flu, chemotherapy,

stroke, or a car accident. Even careful lifestyles and health regimes do not negate eventual age-related

changes. Individual changes occur asynchronously as a function of genetic makeup, lifestyle, and other

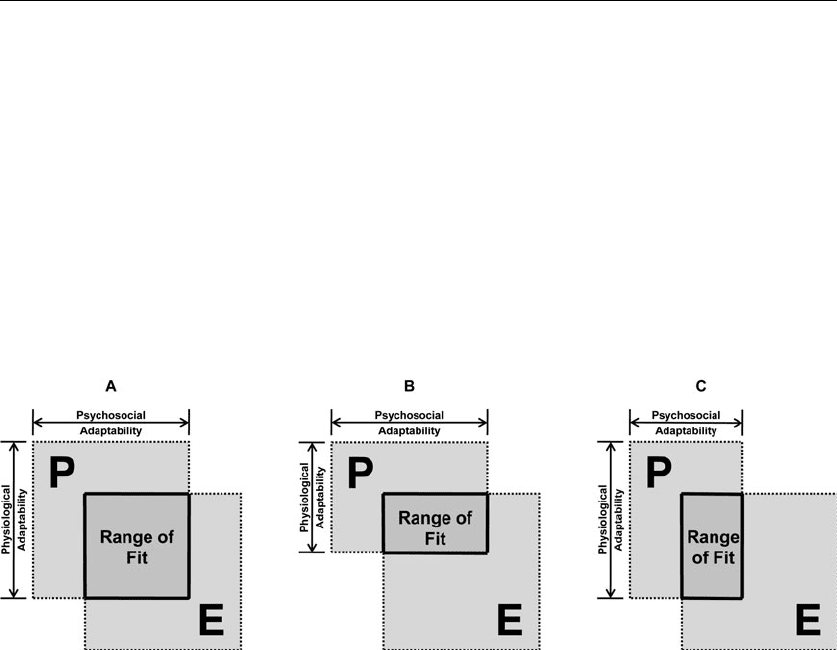

factors. Representational models, therefore, are snapshots in time. Figure 43.4 illustrates how physical

or psychosocial changes of a person (P) cause changes to the range of fit.

FIGURE 43.4 The sequence of diagrams illustrates (A) the person’s unique attributes, (B) a decreased range of fit as a reduction in the

person’s psychosocial attributes, and (C) a decreased range of fit as a reduction in the person’s physiological attributes.

Long description: Figure 43.4 uses three diagrams (A, B, and C) to illustrate the change in range of fit when a person’s physiological and

psychosocial adaptability is reduced.

Figure 43.4A illustrates the full range of human functioning along both physiological and psychosocial continuums (defined in Fig. 43.2).

Figure 43.4B illustrates a reduction in a person’s physiological adaptability. A shorter, vertical dimension for physiological adaptability

is drawn while the psychosocial adaptability dimension remains unchanged. The range of fit is smaller than previously illustrated as the

person’s physiological adaptability is smaller. Therefore, the person is now represented by a wide, short rectangle. The resultant intersection

illustrating range of fit is also a wide, short rectangle.

Figure 43.4C illustrates a reduction in a person’s psychosocial adaptability. A more narrow, horizontal dimension for psychological adapt-

ability is drawn while the physiological adaptability dimension remains unchanged. The range of fit is smaller than previously illustrated as

the person’s psychosocial adaptability is smaller. Therefore, the person is now represented by a tall, narrow rectangle. The resultant intersec-

tion illustrating range of fit is also a tall, narrow rectangle.

REDEFINING DESIGN AND DISABILITY: A PERSON-ENVIRONMENT FIT MODEL 43.5

Human functioning also can be measured in discrete units on a variety of scales. Additionally,

some factors will be more relevant than others in particular contexts. Cognitive functioning may be

significant in employment type and performance but not relevant in social relationships. Decreased

visual acuity may prevent one from playing baseball but not influence one’s ability to work collab-

oratively, to perform housekeeping or parenting tasks. Variation in either psychosocial or physiologi-

cal adaptability circumscribes the potential range of fit, from person to person. Figure 43.4 illustrates

how physical or psychosocial differences from person to person lead to different ranges of fit.

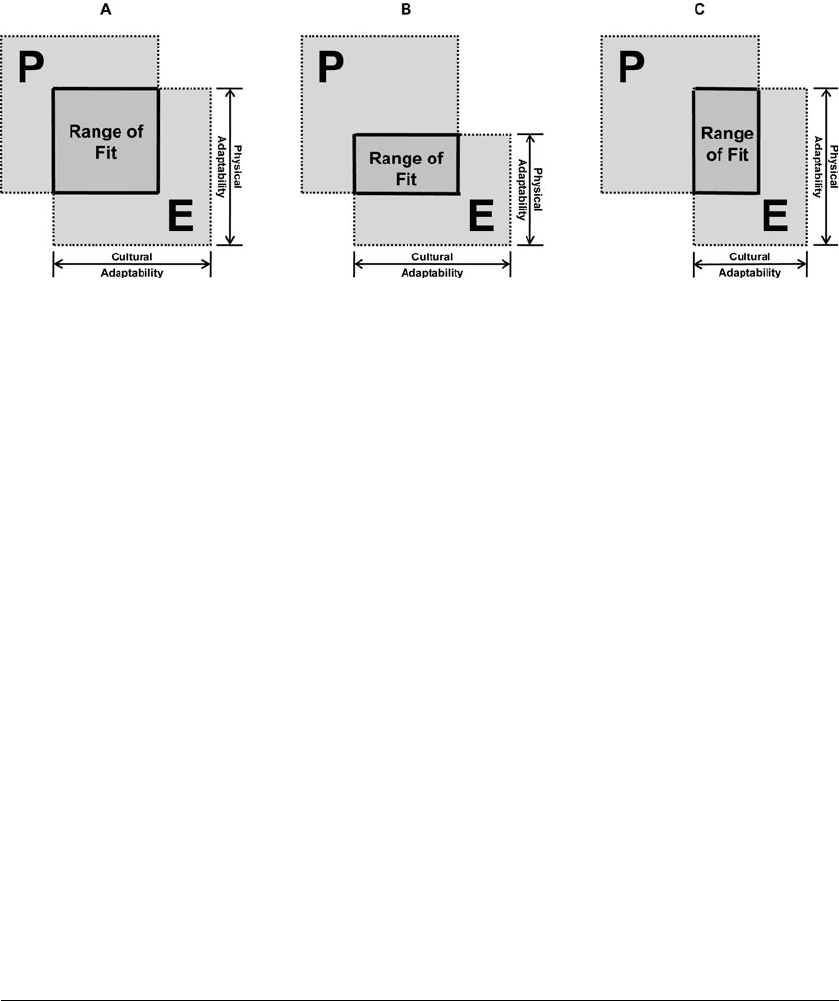

If each person is unique, so, too, is each environment. Environments possess similar ranges of diver-

sity. For instance, temperatures vary by more than 100 degrees from one region to the next. Likewise,

services enabling independent living, e.g., job training, health care, and housing advocates, may be

diverse in urban areas or nonexistent in rural settings. Figure 43.5 illustrates how physical or cultural

differences from one environment to the next lead to different fits. These same factors may also change

over time. Most public buildings, for instance, host a wide range of users over time. A hotel hosts a

wedding reception one weekend and serves as the conference site for a local area agency on aging the

next. Rural schools likewise house students during the day, extracurricular activities in the afternoon,

and community groups in the evening. As such, multiple functions and multiple user groups require

design solutions that are responsive and inclusive. Similarly, weather, position of the sun, and rainfall

changes over the course of a day, a week, or a season influence building performance and context.

43.4 RECIPROCITY OF THE PERSON-ENVIRONMENT

RELATIONSHIP

What universal design, visitability, life span design, and similar concepts illustrate is that the physi-

cal and cultural aspects of the environment and the physical and psychosocial aspects of people are

interrelated. When the environment exerts pressure on the individual that falls within the person’s

FIGURE 43.5 The sequence of diagrams illustrates (A) the environment’s unique attributes, (B) a decreased range of fit as a reduction in

the environment’s cultural attributes, and (C) a decreased range of fit as a reduction in the environment’s physiological attributes.

Long description: Figure 43.5 uses three diagrams (A, B, and C) to illustrate the change in range of fit when an environment’s physiological

and cultural adaptability is reduced.

Figure 43.5A illustrates the full range of environmental factors along both physiological and cultural continuums (defined in Fig. 43.2).

Figure 43.5B illustrates a reduction in an environment’s physiological adaptability. A shorter, vertical dimension for physiological adapt-

ability is drawn while the cultural adaptability dimension remains unchanged. The range of fit is smaller than previously illustrated as the

environment’s physiological adaptability is smaller. Therefore, the environment is now represented by a wide, short rectangle. The resultant

intersection illustrating range of fit is also a wide, short rectangle.

Figure 43.5C illustrates a reduction in an environment’s cultural adaptability. A narrower, horizontal dimension for cultural adaptability

is drawn while the physiological adaptability dimension remains unchanged. The range of fit is smaller than previously illustrated as the

environment’s psychosocial adaptability is smaller. Therefore, the environment is now represented by a tall, narrow rectangle, and the envi-

ronment remains a square. The resultant intersection illustrating range of fit is also a tall, narrow rectangle.

43.6 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

range of functioning, the adaptive range is considered positive. Generally, this adaptive range would

mean that the individual finds the environment to be challenging in a positive way because skills and

abilities are being used. When the pressure falls outside of the person’s range of functioning, adapta-

tion may be negative as a function of atrophy or discouragement (Lawton and Nahemow, 1984).

For example, for a traveler with Parkinson’s disease, traversing the distance between airport secu-

rity and the boarding gate could be hazardous. Transitions from carpeted to hard surfaces designed to

delineate space are difficult for individuals with shuffling gaits. Moving sidewalks, instead of facili-

tating movement, are treacherous for those with balance and reflex impairments. Trams designed

to shorten travel time are only accessible to those capable of quick, well-controlled movements.

Airports can exert pressure on persons with disabilities that fall beyond their range of functioning.

Thus, an environment designed to facilitate movement behaves as a dynamic impediment to those

whose range of functioning exists outside the reciprocity of the P-E relationship.

Just as important as specific reciprocity, as individuals pursue their daily activities, is the need

for a broad range of spaces and places to incorporate inclusive design solutions. The range of P-E fit

encompasses micro- and macroenvironments, as well as the continually changing range of function-

ing across the life span. We all want to live in a livable community. The reciprocity of a community

plays a major role in facilitating independence and inclusion. A safe pedestrian environment, easy

access to grocery stores and other visitable shops, a mix of housing types, and nearby health centers

and recreational facilities are all essential elements that can positively affect the range of P-E fit.

43.5 CONCLUSION

The proposed model suggests that aspects of persons and their environments are contextual and

circumstantial. People and their environments are not static entities. Human functioning changes on

a moment-by-moment basis due to environmental factors, such as weather or location, as well as

human factors, such as activity or illness. Similarly, preferences and needs change as life circum-

stances and roles change. Individuals must balance priorities and resources with needs and prefer-

ences. In spite of these forces, however, fit can be transformed.

Purposeful manipulations must be carefully weighed against one another to create a good person-

environment fit. First, the interdependence of the major facets of fit—person and environment—

must be understood. Second, person-environment fit must be assessed across scales: federal to local,

policy to practice, and society to individual. Third, P-E fit must be understood across domains:

health and housing, needs and preferences, physical and psychosocial. Finally, policy makers, health

professionals, design and construction professionals, and the general public need to understand the

ever-changing status of person, environment, and resultant fit, not categories.

Fit is a dynamic and complex process. The person-environment relationship is contingent upon

the complexities of human intentions and changing priorities of the individual’s role at a particular

time and place. Improving person-environment fit requires changes to the person, the environment,

or both, requiring emotional, physical, and/or monetary resources by individuals, families, society,

or all the above (see Fig. 43.6). For example, alterations to the environment require materials, labor,

money, and time. In parallel, changes to individual health, aptitude, knowledge, and attitudes require

financial and other resources. In some cases, improving fit may necessitate a combination of medical

and design interventions. As a result, inadequate fit is sometimes not fully addressed. Nevertheless,

as with Ed Roberts, personal and environmental challenges need not be viewed as insurmountable,

but can be viewed as catalysts for innovation.

It is critical for the proposed model that fit be defined by the interface of persons and environ-

ments at all scales. As the P-E fit model illustrates, variability is the norm. While the medical

model focuses on the person, universal design (UD) focuses on the environment. The P-E fit model,

however, illustrates the relevance of both, and that design interventions can be in either realm (P

or E) as a means to improve fit. If the costs of improving fit are examined, it becomes clear that

for some individuals, a medical intervention—pharmaceutical, surgical, psychological, or physical

therapies—may be the most effective method of improving functioning. Medical interventions can,

REDEFINING DESIGN AND DISABILITY: A PERSON-ENVIRONMENT FIT MODEL 43.7

at times, be the least invasive, least stigmatizing, and/or least costly of available options. In parallel,

modifications to the cultural or physical environment may be the most effective or necessary means

of improving fit. The P-E fit model places the onus neither on medical intervention nor on design,

but rebalances the two, more accurately reflecting the realities of unique individuals in particular

environments.

Through this model, the concept of UD evolves. The transformed definitions of (dis)ability and

design allow for the separation of UD from its historical roots as a response to “specialized design”

for “special” populations. Alternately, in the construct of the P-E fit model, UD comes to exemplify

the fluid and contextual nature of people in the environment. Like many college students, Ed Roberts

wanted to “go out and drink a little” (Shapiro, 1994). Later in life, like many parents, his priorities

shifted toward family. While Ed’s particular circumstances may have been “special,” the overarching

goal of achieving fit, as both a student and a parent, was universal. As such, the task for UD propo-

nents may very well be to acknowledge the limits of environmental design as well as the vastness

of human conditions.

FIGURE 43.6 This diagram illustrates the person’s and the environment’s unique range of

attributes in the context of all possible variation in people and their environments.

Long description: Figure 43.6, through the compilation of the previous figures, illustrates the

comprehensive person-environment fit model.

As described earlier, the model is comprised of two large squares, representing the person and

the environment, arranged diagonally with the overlap representing the range of fit (Fig. 43.1).

This arrangement exists inside a larger square, which represents the context of all possible

people and environments. The diagram held inside the square, therefore, represents a specific

individual in a specific environment.

43.8 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

43.6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Altman, I., and M. Chemer, “Introduction,” Culture and Environment, CUP Archive, 1984, pp. 8–11.

Bronfenbrenner, U., Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development,

Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage, 2005.

Brubaker, R., and F. Cooper, “Beyond ‘Identity,’” Theory and Society, 20(33), 2006.

Caplan, R., S. Cobb, J. French, R. V. Harrison, and S. Pinneau, Job Demands and Worker Health, Cincinnati,

Ohio: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, 1974.

Gibson, J., “The Theory of Affordances,” in Perceiving, Acting, Knowing: Toward an Ecological Psychology,

R. Shaw and J. Bransford (eds.), Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1977, p. 174.

Lawton, M. P., and L. Nahemow, “Ecology and the Aging Process,” in Psychology of Adult Development

and Aging, C. Eisdorfer and M. P. Lawton (eds.), Washington: American Psychological Association, 1973,

pp. 619–674.

Rae, A., “What’s in a Name?” International Rehabilitation Review, 1989, accessed Mar. 2, 2009; http://www.

leeds.ac.uk/disability-studies/archiveuk/Rae/Whatsname.pdf.

Reda, S., “The Quest for Levi’s,” Stores, 88:10, 2006.

Shapiro, J., “From Charity to Independent Living,” No Pity: People with Disabilities Forging a New Civil Rights

Movement, New York: Times Books, 1994, p. 45.

U.S. Census Bureau. Population Division: Racial and Ethnic Classifications Used in Census 2000 and beyond,

Washington, Apr. 10, 2008; http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/race/racefactcb.html.

World Health Organization, International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities, and Handicaps: A Manual

of Classification Relating to the Consequences of Disease, Geneva, Switzerland, 1980.

———, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: IQ, Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

THE PAST AND FUTURE OF

UNIVERSAL DESIGN

P

O

A

O

R

O

T

6

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER 44

THE RHINOCEROS SYNDROME:

A CONTRARIAN VIEW OF

UNIVERSAL DESIGN

Jim S. Sandhu

44.1 INTRODUCTION

As overlapping design philosophies, universal design (UD), human-centered design, or the preferred

European terms inclusive design (ID) and design-for-all have come a long way since their inception.

Despite their separate beginnings, their overarching concepts developed in parallel. They all have

two common origins: (1) the disability movement and (2) the impact of user-centered design on

quality of life. In the context of this chapter, the abbreviation ID covers them all in a general sense,

while UD refers specifically to American developments.

As can be gleaned from various chapters in this book, by far the most positive evolutionary

change has been a move away from a particular group of people to a broader population regarding

the impacts of design. Nevertheless, there remains a gap between theory and practice, indicating

both problems and limitations. There is an urgent need to understand what these are in order to

help rectify and to make the various approaches more effective. One key problem is the lack of

application of UD/ID in the majority world (see Chap. 3), where even small changes can make a

tremendous difference to the quality of life. Despite various claims, few practitioners are involved in

UD/ID that affects the majority world. Another major stumbling block to evaluating the benefits of

the UD approach is the recent practice of labeling conventional use of good human-centered design

as UD. Adherents of the latter frequently incorporate these as exemplars and outcomes of the seven

Principles of Universal Design (see Chap. 4).

Alongside the shift in focus to as many potential beneficiaries of good design as possible, where

the prime objective was on usability and functionality, there is now an increasing trend to open

UD/ID to include wider social, political, and legal issues. While this broadening of the concept is

interesting and challenging, it is seriously worrying in epistemological terms. In some cases, UD/ID

has moved away from the activity of designing, i.e., producing objects and environments for users,

to mere abstractions, such as codes and standards authoring. Problems have resulted in sorting out

UD/ID approaches, outcomes, principles, impacts, methodologies, and standards. This is not to be

little the fact that demographic, legislative, and social changes are keys to understanding the broader

implications of UD/ID. This broadening is of serious concern in the light of the seven principles, as

they only apply to design and designing.

The author remembers the misinterpretation of the conference title Design for the 21st Century

by many nondesigner friends who thought it was a new utopian approach to sort out the whole of

society. In a similar vein, the author remembers the tussle between the promoters of design methods

in the 1970s and its opponents. The latter did not acknowledge that design methods had anything

44.3