Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

41.2 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

Three years later, the United Nations (1993) adopted standards for accessibility. While these efforts

have led to improvements in accessibility, Lawton (2001) argues that they do not respond to the full

spectrum of human needs and do not address affective experience. An environment may afford basic

accessibility and satisfy a range of needs (such as, safety, function, cognition, autonomy, privacy,

stimulation, and affiliation). It may fail, however, to afford satisfactory affective experience, in rela-

tion to psychological comfort and perceived dignity of individuality (Lawton, 2001; Preiser, 1983).

The ADA is a civil right. Section §302a states that “No individual shall be discriminated against

on the basis of disability in the full and equal enjoyment of the goods, services, facilities, privileges,

advantages or accommodations of any place or public accommodation.” [author’s italics]

Do entries retrofitted to meet the ADA minimum standards of access give people who need to use

them “equal enjoyment” to the front entrance available for people who can walk in?

Universal design calls for more than the minimum standards of accessibility set by the ADA.

Brown v. Board of Education set the precedent that “separate is not equal.” Following this prec-

edent, universal design, in its call for equity and social justice, is socially inclusive and calls for

designs that “can be used by everyone” (Mace, 1988; Mace et al., 1991). It has seven principles:

(1) equitable use, (2) flexibility in use, (3) simple and intuitive use, (4) perceptible information,

(5) tolerance for error, (6) low physical effort, and (7) size and space for approach and use (Center

for Universal Design, 1997; Preiser, 2007). While all these principles apply to building entries, one

has special relevance to the psychological experience of retrofitted ones: principle 1, equitable use.

For equitable use, everyone should have equal access to places. Consider retrofitted entries in terms

of selected aspects of equitable use. Do such entries give all users the same means of use, identical

when possible and equivalent when not? Do they avoid segregating or stigmatizing any users? Do

they make provisions for privacy, security, and safety equally available to all users? Are the designs

appealing for all users?

The seven Principles of Universal Design have three additional levels: guidelines, tests, and strate-

gies (Center for Universal Design, 1997). The present research centers on the second level—tests—in

relation to equitable use. Preiser (2007) referred to three levels of performance criteria for universal

design: (1) health, safety, and security; (2) function and efficiency; and (3) the social, psychological,

and cultural. The present study examined the psychological experience of building entries (from the

third level). An earlier study had found that non-wheelchair users judged the routes for retrofitted

entrances as least pleasant, the routes for the old main entrances as more pleasant, and the routes for

the new accessible entrances as most pleasant (Nasar, 2009). Would those results hold for people who

use wheelchairs and other aids to accessibility? The present study had several expectations.

1. For older buildings and setting aside concerns of accessibility, people who use wheelchairs and

other mobility aids will judge the experience of main entry routes as more pleasant than retrofit-

ted ones.

2. They will judge the experience of new (universally designed) entry routes as more pleasant than

retrofitted ones.

3. They will judge the experience of new (universally designed) entries routes as more pleasant than

old (less accessible) main entries.

The latter two represent lesser expectations because the test of these involves at least one other vari-

able (building age) that may bias the results in favor of the newer entries.

41.3 METHOD*

To get participants, the researcher e-mailed four people who might have access to lists of people who

use wheelchairs and asked them to circulate an e-mail request to participate in the study.

*All procedures were performed in compliance with relevant laws and institutional guidelines.

ARE RETROFITTED WHEELCHAIR ENTRIES SEPARATE AND UNEQUAL? 41.3

There were 24 people (8 males, 10 females, and 6 who did not indicate their gender). The mean age

(n = 18) was 52.2 years (SD 11.2 years), making them older than the sample in study 1. Most described

themselves as Caucasian (62.5 percent), with a college degree or more (75.0 percent), married (54.2

percent), and more reporting no children under 18 living at home (45.8 percent) than those reporting

one or more children living at home (33.9 percent). Also 20.8 percent did not report their race/ethnicity,

education, marital status, or number of children living at home. Some reported that they were single

(12.5 percent), divorced (8.3 percent), or other (4.2 percent). In addition, 16.7 percent reported one

child living at home, 12.5 percent reported two, and 4.2 percent reported three or more. Also 4.2 percent

had some college or an associate’s degree, 37.5 percent were college graduates, 12.5 percent had a

graduate degree, and 25.0 percent had a postgraduate degree. Three participants were eliminated from

the study, because they did not complete the ratings, resulting in a sample of 21 people.

Each participant saw and evaluated 29 building entry routes in one of four different orders.

This sample came from 24 older buildings selected at random on the main campus of The Ohio

State University. The sample included photos of the old and retrofitted entry route for 12 buildings

plus the entry routes for 5 newer buildings, each of which had a main entrance usable by walkers

and people who use wheelchairs or walking aids. These entries had powered doors with remote but-

tons. While these entries would not be considered universally designed (because they require more

interaction than no doors, “air doors,” power doors with a motion detector, or powered doors with a

pressure sensor mat), they require less interaction than many other doors (Mace, 1988). Each route

was photographed at equal intervals, or where the route changed direction. For each, participants

would see a sequence of digital photographs of the route to the main atrium from the main entry, and

from the retrofitted ADA entry. Research indicates smaller size effects from participants than from

the environment (Stamps, 1999). The analyses centered on the entry conditions for old buildings,

retrofitted buildings, and new buildings (see Figs. 41.1 through 41.4 for examples of each).

To lessen order effects, participants saw the entry routes in one of four different orders. They

responded via an online survey. The e-mail request for participants asked people to go to one of four

web sites depending on the first letter of their last name. This resulted in 8, 10, 5, and 2 respondents

for each order of the entries.

The routes for wheelchair users and others using walking aids required more photographs on

average (retrofitted entrance: mean = 14.77 photos, SD 6.37) than the routes for the older main

entrances (mean = 6.31 photos, SD 1.84) and the new entrances (mean = 8.2 photos, SD 0.84). In

addition, while many of the retrofitted entries were on the side or back of the building, no signs were

found directing people to them. Although the study intended to focus on equitable use, the selection

of the stimuli suggested that compared to other entrances, retrofitted entrances were less simple and

intuitive to use, had less perceptible information, and required more physical effort; and in terms of

those criteria, they were not equitable in use.

The survey instructions told respondents that the research team was studying people’s evalua-

tion of building entrance routes. They would see a sequence of photos of routes into buildings and

rate the pleasantness of each route on a 7-point scale for pleasantness (from very unpleasant to very

pleasant). To have them focus on the pleasantness of the route rather than its accessibility (the retro-

fitted routes were more accessible than the old ones), the instructions stated that “while accessibility

is important, the survey centers on visual quality. It aims to assess the visual quality of building

entrance routes. When evaluating each route, please ignore barriers to access (such as stairs, nar-

row doors, etc.). Imagine you are floating through the route, and simply rate the pleasantness of the

experience of the route.” The instructions indicated that there were no right or wrong answers, and

the research team was interested only in their honest opinions.

41.4 RESULTS

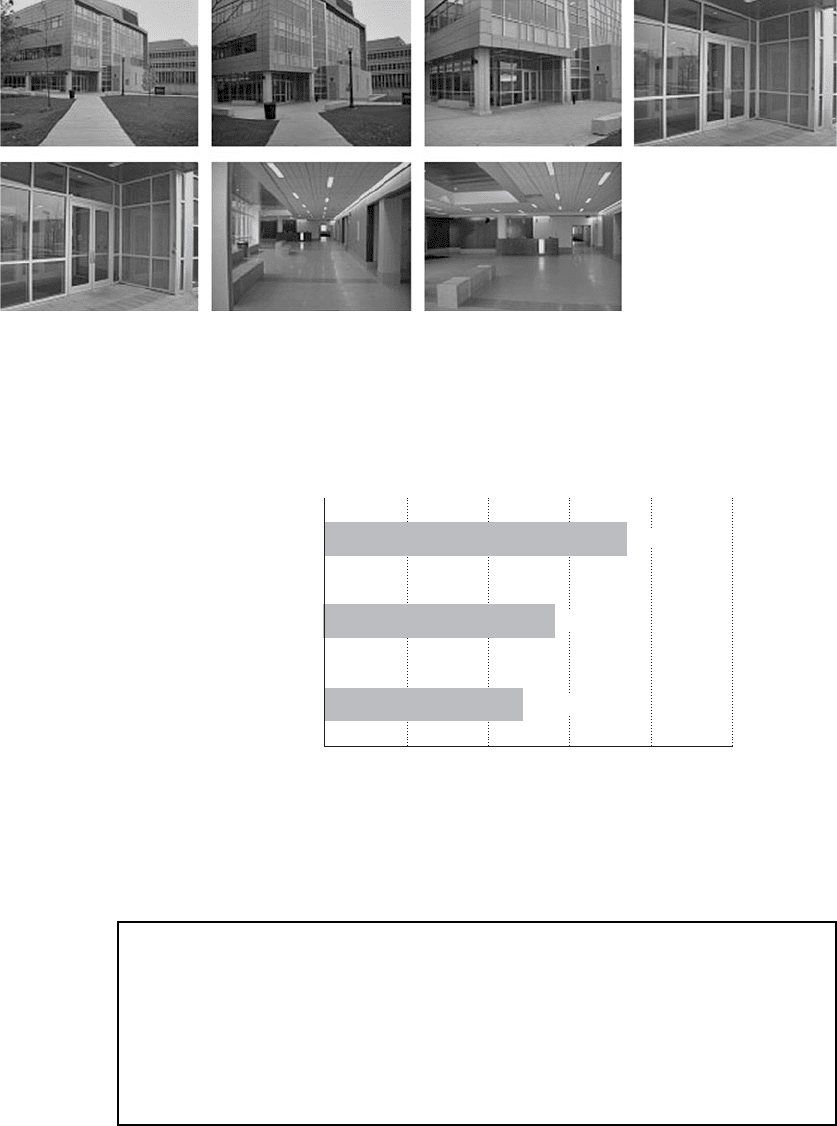

The results confirmed that the retrofitted entries are perceived as separate but not equal. Participants

rated the “equal access” entries as most pleasant, the retrofitted entries as least pleasant, and the “old

main” entrances as in between (see Fig. 41.5). These differences achieved statistical significance

41.4 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

Building

Old Main Entrance

Retro Fitted Entrance New (accessible)

Entrance

Weigel

Hall

Sullivant

Hall

Caldwell

Brown Hall

Orton Hall

Derby

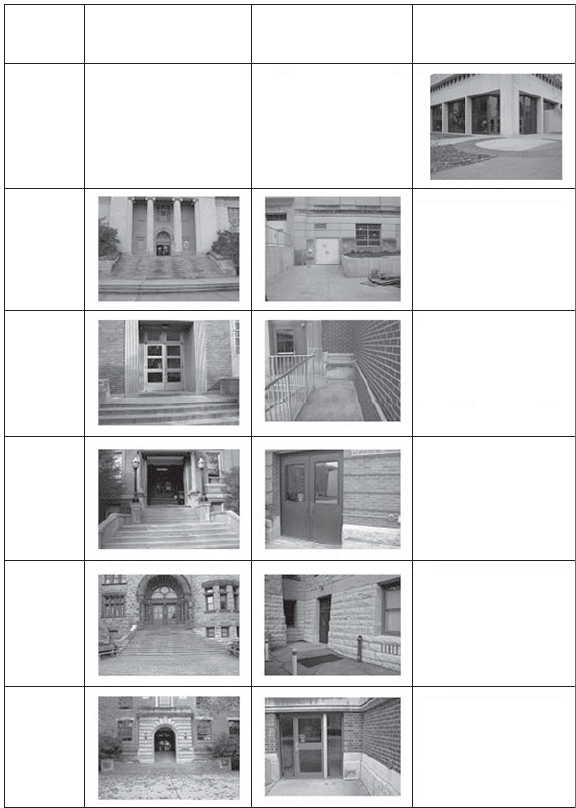

FIGURE 41.1 A table with three columns shows photos of 12 pairs of old main and retrofitted

entrances, plus 5 new (accessible) entrances to new buildings.

Long description: The figure shows photos of 12 main entry routes, 12 retrofitted entry routes

to the same buildings, and 5 new (accessible) entrances to new buildings. The main entries

are designed to communicate that they are the main entrance. They often have large doors,

set back and framed by building ornament or an arch, and steps leading up to them. The ret-

rofitted entrances often look undistinguished. They are plain side or back service entries. The

new (accessible) entrances to new buildings are designed to communicate that they are main

entrances, but they have no stairs blocking access.

ARE RETROFITTED WHEELCHAIR ENTRIES SEPARATE AND UNEQUAL? 41.5

Health Center

Psychology

Math Tower

Main Library

Scott

Laboratories

Wexner

Center

Page Hall*

Baker

Systems

FIGURE 41.1 (Continued)

41.6 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

Classroom

Services

Knowlton

Hall

Faculty

Club

* The renovation of page (completed in 2006) at the time of the study replaced the former main entry

(shown on the right) with the entrance shown. However, because wheelchair users can only access it

through an indirect route, we included the two routes in the study as old and retrofitted.

FIGURE 41.1 (Continued)

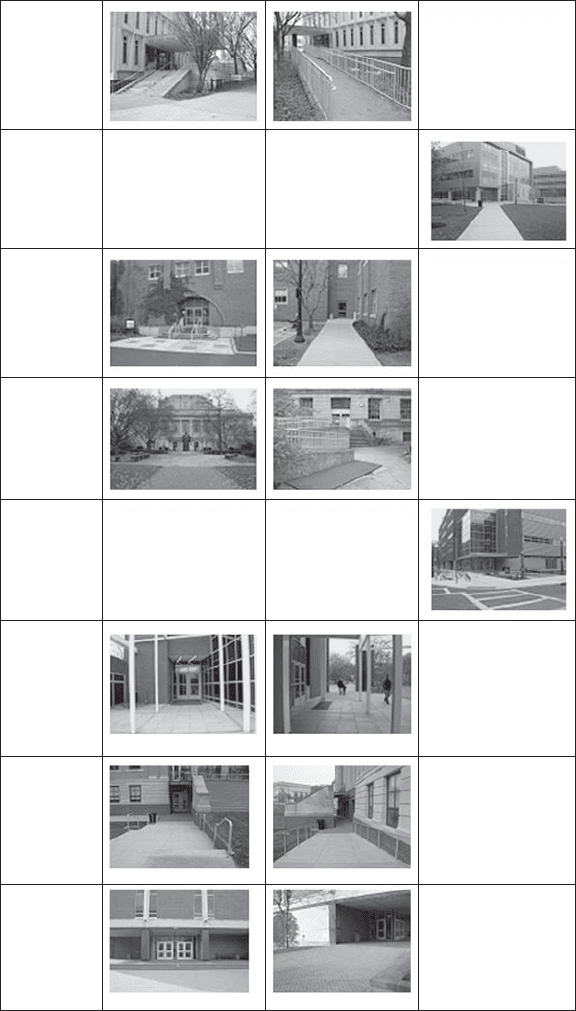

FIGURE 41.2 Eight-photograph sequence from outside, toward an arch-enclosed double door, up the stairs to the double door, into the

ornate atrium space, down a hall to the main interior stairway and elevator.

Long description: The figure is an eight-photograph sequence from the outside of an old main entrance into the building, and to its main

interior stairway and elevator. The first photo shows the raised arch-enclosed entrance in the distance. The second one (horizontally) shows

a closer view (about 5 yd away) of the same entrance. The third one takes you inside the arch to the stairway of 15 stairs leading to the main

double door. The fourth shows a close-up of the tall metal-framed glass double door. The fifth brings you inside the building to an ornate atrium,

which has a row of white columns, with wood benches between them, on each side, one bright square overhead light, an ornate marble floor,

and an exit door (similar to the entrance one) beyond the columns. The sixth shows an open door into a plain corridor. The seventh shows the

plain corridor, which has carpet, hung ceiling with three overhead fluorescent light boxes, and two doorway alcoves on each side. The last photo

shows an open area, with a stairway to the left, and another plain corridor straight ahead.

ARE RETROFITTED WHEELCHAIR ENTRIES SEPARATE AND UNEQUAL? 41.7

FIGURE 41.3 Thirteen-photograph sequence of retrofitted route from outside the same building as in Fig. 41.2 through a convoluted path

to the same open area with the interior stairway and elevator.

Long description: The figure is a 13-photograph sequence from the outside of a building along the retrofitted route into the building and to

its main interior stairway and elevator. The first photo shows the same raised arch-enclosed entrance in the distance as the first photo in

Fig. 41.2. The second photo (horizontally) turns left to a tree-lined path. The next three photos (3 through 6) move along the tree-lined path.

The seventh photo, along the same path, shows a bike rack with three bikes on the left and the building on the right. The eighth photo moves

past the bike rack (to the last bike) and shows a 6-ft-high brick wall on the right. The ninth photo shows a more open view. The ninth photo

turns right toward a single steel-framed glass door, with panels of glass on each side. The tenth photo moves closer to the door. The eleventh

photo shows a view inside from the door to a small space with an elevator about 5 ft away. The twelfth photo shows the view from inside the

elevator looking out as the metal elevator door closes. The thirteenth photo shows the same open area as the last photo in Fig. 41.2.

(F

2,927

= 46.20, p < 0.001). Post hoc comparisons between each pair of entry routes separately (old

main versus retrofitted, old main versus equal access, and equal access versus retrofitted) showed

that participants rated the equal-access entries as more pleasant than either the old or retrofitted one,

and that participants rated the old entries as more pleasant than the retrofitted ones, and these differ-

ences achieved high levels of statistical significance (p’s < 0.001). According to Cohen (1988), in the

social sciences, effect sizes vary from small (d = 0.20) to medium (d = 0.63) to large (d = 1.16). The

comparison of the equal access to the old main and the comparison of the old main to the retrofitted

entrances represented medium-size effects; and the comparison between the equal-access and the

retrofitted entries represented a large effect.

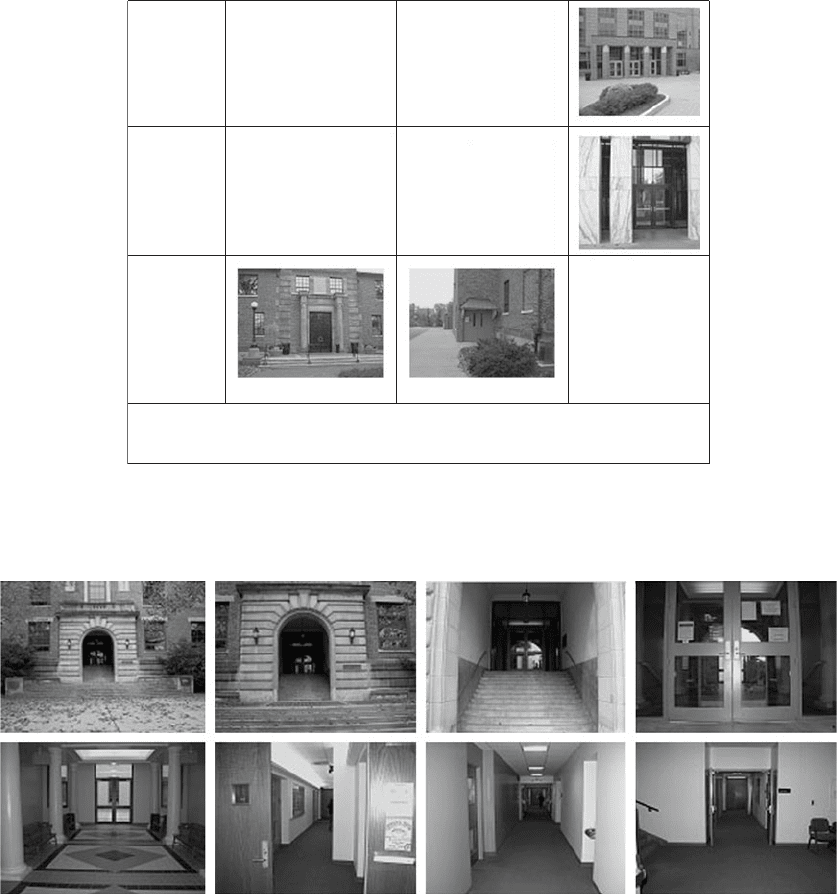

FIGURE 41.4 Seven-photograph sequence from outside a new building with an equal-access entry to the main interior atrium with elevator

and stairway.

Long description: The figure is a seven-photograph sequence from outside a new building through its equal-access entry to its main interior

atrium with elevator and stairway. The first photo shows a diagonal path toward a corner indented entrance on a four-story primarily glass

and steel building. The second photo (horizontally) moves closer to the entry. The third photo shows a roughly 20-ft

2

concrete area outside

the entrance and the entrance. The fourth photo moves toward the double glass door entrance. It is in an enclosed place, at the far end of a

glass and steel wall on the left. A similar wall straight ahead helps frame the entrance. The fifth photo moves closer to the double glass door.

The sixth photo shows the view inside the door of a wide, shiny, well-lit corridor, with glass to the right and what looks like a broader open

space farther ahead to the right. The seventh photo shows the well-lit, shiny, open atrium space.

Equal access

Old main

Retrofitted

123456

3.42 (1.69)

3.84 (1.70)

4.71 (1.70)

Type of Entry

FIGURE 41.5 A bar graph shows that people rated the equal-access entries as most

pleasant, followed by the old main entrances, and then the retrofitted entrances.

Long description: A horizontal bar graph for pleasantness ratings. The top bar (the longest)

is labeled equal access and has a mean score of 4.17 and standard deviation of 1.70. The

next bar, shorter, is labeled Old Main and has a mean score of 3.84 and a standard deviation

of 1.70. The third bar, the shortest, is labeled retrofitted and has a mean score of 3.42 and

a standard deviation of 1.69.

Recommendations

• Consider the visual appeal of the entry route for people who use wheelchairs or other

aids to walking.

• Retrofi tted entry routes, in addition to being accessible, should be appealing. When

retrofi tting an entry for wheelchair access, design the route and its characteristics to

look good.

• For the best entrance experience for access and visual appeal, use a universally

designed entrance, usable by everyone.

41.8

ARE RETROFITTED WHEELCHAIR ENTRIES SEPARATE AND UNEQUAL? 41.9

41.5 CONCLUSION

The Americans with Disabilities Act calls for “equal enjoyment” and, as a civil right, recognizes

that separate is not equal. The results suggest that buildings retrofitted for wheelchair access offer

separate but not equal entrances. Participants judged such entrance routes as least pleasant. Although

the entrances to new buildings did not have the highest level of universal access, the remote, auto-

matic door opener button did offer substantial access; and participants rated them as the most pleas-

ant. Perhaps doors requiring less interaction by users (Mace, 1988) would achieve higher scores.

However, this preference for the new entries may be an artifact of building age, design standards,

and upkeep. The building with new entries opened a year or two before the study, while the newest of

the other buildings opened more than 25 years before the study. Future research could use controlled

simulations to test people’s responses to entries varying in the level of interaction required.

Although it had a diverse sample of respondents, the study did not gauge long-term exposure to the

entrances. People who use wheelchairs and other mobility aids must repeatedly use retrofitted entries

every day. They do not have a choice (or control); and the repeated exposure to such separated and pos-

sibly stigmatized entries and the lack of perceived control might well depress the perceived quality of the

experience, but it is possible that they adapt to the experience and thus perceive it as more acceptable.

This study centered on buildings on the main campus of The Ohio State University in Columbus.

Perhaps different results would emerge for other campuses or other kinds of buildings. In addition,

the static photographs (even though shown in sequence) probably evoked less intense responses than

would occur for dynamic experience (Heft and Nasar, 2000). Future work should test on-site evalu-

ations of entries to a variety of public and private facilities by people who use wheelchairs, walking

aids, and others to ascertain their dynamic real-world experience.

To meet the integration requirement implicit in ADA, people with disabilities should, if possible,

enter from the main entrance. A “practicality” exception may apply to historic front entrances that

would have to change to become accessible, or to topographical issues that would make a ramp to

the front entrance too steep. Because of the degree to which some side and rear entrances lack full

functionality (because they are locked, require assistance, or do not result in entry to the main area),

they do not comply with the ADA policy preference toward integration.

Beyond basic functionality, the present research looked at the psychological experiences of

various participants. Universal design has the promise of “lifting the spirit beyond the minimum

requirements of the Americans with Disability Act” (Preiser, 2007, p. 11). Vision dominates human

experience of the environment. To lift the spirit and have equitable use, entrances and other aspects

of the design should, at a minimum, look appealing to all users and avoid segregation and stigmatiza-

tion. They should integrate rather than segregate users.

41.6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Americans with Disabilities Act, U.S. Pub. L. 101-336, 104 Stat. 327, July 26, 1990.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 1954.

Center for Universal Design, Principles of Universal Design, Version 2.0, Raleigh: Center for Universal Design,

North Carolina State University, 1997.

Cohen, J., Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2d ed., Hillsdale, N.J.: Erlbaum, 1988.

Heft, H., and J. Nasar, “Evaluating Environmental Scenes Using Dynamic versus Static Displays,” Environment

and Behavior, 3:301–323, 2000.

Lawton, P., “Designing by Degree: Assessing and Incorporating Individual Accessibility Needs,” in Universal

Design Handbook, 1st ed., W. F. E. Preiser and E. Ostroff (eds.), New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001, pp. 7.1–7.14.

Lynch, K., The Image of the City, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1960.

Mace, R., Universal Design, Barrier Free Environments for Everyone, Los Angeles: Designers West, 1988.

———, R. G. Hardie, and J. P. Plaice, “Accessible Environments: Toward Universal Design,” in Design

Interventions: Towards a More Humane Architecture, W. F. E. Preiser, J. C. Vischer, and E. T. White (eds.),

New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991, pp. 155–176.

41.10 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

Nasar, J. L., “Are Retrofitted Wheelchair Entries Separate and Unequal?” Paper presented at American Collegiate

Schools of Planning Conference, Crystal City, Va., Oct. 1–4, 2009.

Preiser, W. F. E., “The Habitability Framework: A Conceptual Approach toward Linking Human Behavior and

Physical Environment,” Design Studies, 4:84–91, 1983.

———, “Integrating the Seven Principles of Universal Design into Planning Practice,” in Universal Design and

Visitability: From Accessibility to Zoning, J. L. Nasar and J. Evans-Cowley (eds.), Columbus, Ohio: Glenn

Institute of Public Policy, 2007, pp. 11–30.

Sandhu, J. S., “An Integrated Approach to Universal Design: Toward the Inclusion of All Ages, Cultures, and

Diversity,” in Universal Design Handbook, 1st ed., W. F. E. Preiser and E. Ostroff (eds.), New York: McGraw-Hill,

2001, pp. 3.3–3.14.

Stamps, A. E., “Demographic Effects in Environmental Preferences: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Planning

Literature, 14:155–175, 1999.

Story, M. F., “Principles of Universal Design,” in Universal Design Handbook, 1st ed., W. F. E. Preiser and

E. Ostroff (eds.), New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001, pp. 10.3–10.19.

United Nations, Standard Rules for the Equalization of Opportunities for Persons with Disabilities, General

Assembly Resolution A/RES/48/96, 1993, accessed July 30, 2007, http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/enable/

dissre00.htm.

CHAPTER 42

GUIDEPATHS IN BUILDINGS

Jon Christophersen and Karine Denizou

42.1 INTRODUCTION

The function of guidepaths is to aid and simplify orientation in buildings. The main aim is to improve

way-finding between important functions or groups of functions. People with visual impairments

are of primary concern, but well-designed and correctly placed guidepaths are helpful for everyone

who attempts to find the way through a complex building. As such, this chapter is based on a study

of guidepaths for persons with visual impairments done by the Norwegian research organization

SINTEFByggforsk (Denizou and Christophersen, 2008).

42.2 RESEARCH ON GUIDEPATHS

The study was limited to conditions inside buildings and was commissioned by the DELTA Centre,

a public body under the Directorate for Health and Social Affairs in Norway. The original project

design focused on test results, evaluations, and practical user experience. However, an extensive

search for literature through libraries and personal contacts in Europe and America gave few results.

Guidepaths in outdoor areas dominate the literature. Studies evaluating and testing guidepaths in

buildings were hard to find and dated from the 1990s or earlier. The available sources thus proved

insufficient to merit a project. It was, therefore, decided that the study would deal with actual, built

solutions and include a brief survey of existing guidelines and regulations. The former includes an

international selection of examples. A comprehensive examination covering all varieties of guide-

paths, however, was not attempted. All that was necessary was simply to record an adequate set of

existing systems and designs to construct a typology. User requirements and testing were included

as a short analysis of the existing literature. Criticism of solutions and requirements were mentioned

where documentary evidence exists, or where problems or successes are clearly evident.

42.3 A TYPOLOGY OF GUIDEPATHS IN BUILDINGS

For the purpose of the typology and an investigation of design elements, guidepaths in buildings

were defined as architectural elements that identify logical lines of connection between focal points.

The term guide path is used in a broad sense and includes architectural elements that guide circula-

tion (such as walls, railings, and parapets); fixtures and ornamentation that indicate lines of traffic

flow; and features that are designed and positioned specifically to aid persons with visual or (in some

cases) cognitive impairments.

42.1