Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

37.6 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

An assumption was made at the start that good projects might not use the language of universal

design or its synonyms of inclusive design or design-for-all. The leaders sent the team on a quest

to identify potential projects to bring to the full team for consideration. They suggested initial

resources such as books, articles, conference proceedings, and IHCD’s international database of

designers. Design media, both print and digital, and the web were a constantly expanding resource

of potential projects. The team met weekly to triage and identify gaps in the categories and in the

geographic regions.

37.6 TOOL FOR GATHERING INFORMATION

In addition to generating the prospect list, the full team worked to build a standard instrument for

gathering information. What do we need to know? From whom do we need to get it? What volume

of information would be necessary to write a narrative? What types of images do we need?

It required many iterations of the form and testing of the tool to generate a final Project

Information Form (PIF). The form asked for a mix of factual information, brief essays in response

to questions, and a range of images, especially those illustrating universal design features. The blank

PIF was nine pages long with one page for internal use. The team designed the PIF to be completed

digitally, and almost all were sent and returned via e-mail.

37.7 CHALLENGES

Completing the demanding form required a substantial commitment of time from the design firm,

which proved challenging. Some firms were immediately responsive and quick to return completed

forms. Most quickly agreed to participate, but required repeated requests with deadlines and exten-

sions, sometimes for many months.

The engagement of user/experts (Ostroff, 1997) was one of the questions to designers. As the case

study project evolved, it was clear that a mix of strategies was needed to deliver an accurate understand-

ing of how well the building worked, such as postoccupancy evaluations. There was no fully reliable

measure of exemplary performance without a site visit from a member of the IHCD team, the jury,

or someone based near the project who could provide a user/expert perspective. It was an imperfect

system, but it caught problems that resulted in some case studies being removed from the collection.

Given that there are substantially more examples of universally designed homes than any other

building type, it was necessary to weigh what to include. In the end, IHCD included homes that

integrated universal design and green sensibilities, in addition to being outstanding in the quality of

design or in places where the project was among the first examples of universal design.

There was little question of Japanese leadership in universal design across all design disciplines.

There were major difficulties in getting full information back on Japanese projects unless the pri-

mary contact was directly with a designer who was bilingual in English. Too often, government

officials responsible for universal design initiatives were the primary point of contact and provided

information suitable for a conference presentation, but not for the case study collection. It was nec-

essary to translate the Project Information Form into Japanese, seek out the designer for case study

projects, and translate from the Japanese as necessary. When all conditions were right, as was the

case with the Nanakuma subway line in Fukuoka, the stellar quality of current Japanese work proved

easy to communicate.

Important audiences for the collection were designers, developers, and advocates across a wide

range of nations. Although attention to universal design is growing, IHCD assumed that there

were limited built projects at that time, which proved true. However, some of the finest examples

of inclusive public realm projects came from Latin America. IHCD hopes that the commitment

to maintaining and expanding the web site will result in capturing emerging nations’ projects as

they are built.

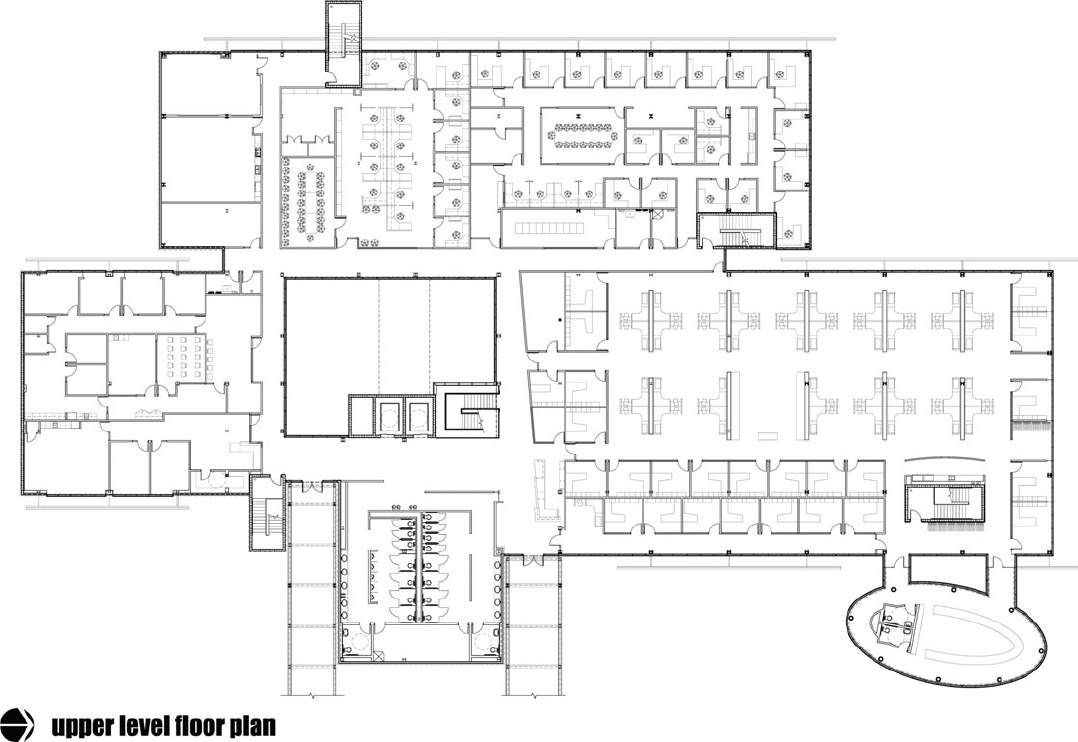

FIGURE 37.3 The Disability Empowerment Center (DEC) of Arizona is a 64,000 ft

2

campus that is an adaptive reuse of a 1970s building.

Long description: The floor plan for the upper floor of the Disability Empowerment Center in Phoenix, Arizona, shows the main office floor of the building and the interior

courtyard center core. The plan shows the attention to accommodating a large number of people who use wheeled mobility. Both the functional and circulation spaces are laid out

to enhance seamless navigation. In addition to corridor windows over a central courtyard, all corridors maximize access to natural light and views.

37.7

FIGURE 37.4 Robert Konieczny designed this country home in Ruda S

´

la

˛

ska in southern Poland with priorities for

ease of use and maintenance, inexpensive materials, and extremely efficient energy use.

Long description: The photo montage shows a mix of images of the simple wood and glass exterior and interior of the small

home revealing the concrete path to the front door with dual side lights and floor-to-ceiling windows in the main living space

with an angled glass ceiling that maximizes natural light and warmth in the cold climate.

FIGURE 37.5 Front façade image of one row of Vandkunsten cohousing in Nødebo, Denmark.

Long description: Image shows a view of the front of a row of homes in Egebakken cohousing in Nødebo, Denmark.

Each private entry is marked by a sloping dark gray zinc roof set back from a walkway which is level with the street and

divided by color, texture, and a lit bollard.

37.8

AN INTERNATIONAL WEB-BASED COLLECTION OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN EXEMPLARS 37.9

37.8 CONCLUSION

Initial expectations proved true that the recent transformation of the definition of good design

includes a commitment to environmental sustainability. As concerns and design ideas proliferate

that focus on human health and well-being as defining qualities of sustainable design, there is more

evidence that places that work for people are also environmentally sustainable.

It is also true that places winning attention and awards reveal a trend toward seamless integration

of inclusive design. It is time to celebrate that evolutionary milestone and to understand the motiva-

tions and practices of exemplary practitioners so that they can inspire replication and innovation.

FIGURE 37.6 The Nanakuma Line, opened in 2005, in Fukuoka, Japan, con-

sists of 16 stations and newly designed railcars.

Long description: The photo of the Nanakuma Line in Fukuoka, Japan, shows a

young woman with large bag pushing a baby in a stroller across a level platform

with a bright yellow tactile strip in the pavement and tactile markings along the

edge across a narrow and level gap into the train.

37.10 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

FIGURE 37.7 The city of Sao Paulo, Brazil, created an inclusive welcoming pedestrian realm in this city of 11 million.

Long description: The photo of Avenue Paulista in Sao Paolo, Brazil, depicts a very wide pedestrian area with zones for walking, street

furniture including benches and shelters, and a boarding area for public transit. The sidewalk measures 25 ft wide, and the surface is smooth

4-in.-thick concrete with precast rubber joints.

There are still frustrating missed opportunities where attitudinal barriers—the “just tell me what

I have to do” mind set—minimize the very real challenge of design that succeeds in transforming

human experience. Unless designers recognize that there are creative frontiers needing explorers and

visionaries in human-centered design, universal design will be condemned to another cycle of rules

outside the engagement and excitement of the design process. If the universal design case study col-

lection succeeds in its mission, it will generate an enticement to be part of something big, to create a

new generation of places that celebrate human diversity while communicating a welcome to all.

37.9 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Lifshez, R., and B. Winslow, Design for Independent Living: The Environment and Physically Disabled People,

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981.

Mueller, J., “Getting Personal with Universal,” Innovation [the quarterly journal of the Industrial Designers

Society of America (IDSA)], Spring 2004, pp. 21–25.

Ostroff, Elaine, “Mining our Natural Resources: The User as Expert,” Innovation, 16(1), 1997.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Gateway to International Best Practices and Innovations, Washington,

accessed April 6, 2009 at http://www.epa.gov/innovation/international/green.htm.

Walsh, C. J., “Sustainable Human and Social Development: An Examination of Contextual Factors,” in Universal

Design Handbook, 1st ed., Wolfgang Preiser and Elaine Ostroff (eds.), New York: McGraw-Hill, 2001,

pp. 33.1–33.16.

World Health Organization, Towards a Common Language for Functioning, Disability and Health, ICF, Geneva:

WHO, 2002.

CHAPTER 38

TOWARD UNIVERSAL DESIGN

PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENTS

Wolfgang F. E. Preiser

38.1 INTRODUCTION

Following the ratification of the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990), the U.S. federal government

has made a sustained effort in creating research centers through the National Institute of Disability

Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) and its funding mechanisms. These centers have focused on topics

ranging from housing to transportation, from wheelchair design to information technology, to name

just a few (IDEA Center, 2007). Only one of these centers had been tasked with developing assess-

ment methodologies (N.C. State Center for Universal Design, in collaboration with Jon Sanford at

the Atlanta VA) over the past 10 years. The only other effort in this regard known to the author was

undertaken in Belo Horizonte, Brazil. Based on his dissertation research at the Center for Universal

Design at North Carolina State University, an attempt was made by Guimaraes (2001) to develop

rating scales for the assessment of universal design.

For the emerging field of universal design to mature and be accepted by the general population

and the design and business worlds, it is imperative for it to become operational in terms of demon-

strable and objectively measurable performance criteria. The purpose of this chapter, then, is to cre-

ate a road map toward the development of universal design (UD) assessment methodology.

A conceptual framework for universal design evaluation was outlined by the author (Preiser,

2001) in the Universal Design Handbook (first edition). It represented an extrapolation from the

building performance evaluation framework first developed and presented in Time-Saver Standards:

Architectural Design Data (Preiser and Schramm, 1997), and was based in part on the author’s post-

occupancy evaluation of medical facilities. In recent years, the number and kind of manifestations of

the field of universal design have been rapidly expanding on a global basis, as is evidenced in new

legislation, public initiatives, conferences, and publications.

The promise of UD as an ideology, however, is contrasted by the sober reality of the implementa-

tion of the seven Principles of Universal Design (Story, 2001). In short, the need exists to align the

principles with building and life safety codes, as well as other design guidelines that set benchmarks

of expected building performance.

38.2 EVOLVING ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK AND METHODS

The history of assessment research in universal design is rather short and consists primarily of case

study evaluations of built projects or developed products, as well as use of expert judgments and

direct, verbal user feedback. Due to the lack of a systematic and comprehensive tool kit of evaluation

38.1

38.2 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

methodologies, the case studies rely primarily on field-based evidence, which is often anecdotal and

observational. In other words, no comprehensive tool kit for assessing universal design exists to this

date. Evaluations or assessments link evaluation methods with the appropriate criteria according to

which a product or design is judged. Traditionally, and as indicated above, such criteria existed in

codified format, such as codes, American National Standards Institute (ANSI) standards, Time-Saver

Standards, as well as agency-specific standards and guidelines, which have evolved over time. In

some cases, and due to intellectual property protection, such standards are not accessible to the pub-

lic. They are guarded heavily by user agencies, such as the military, chip-making corporations such

as Intel, or global consumer goods manufacturers, such as Procter & Gamble. Since UD primarily

addresses the human dimension of designed products and environments, it makes sense to create an

evaluation framework according to the scale of the item being evaluated (see Table 38.1).

For example, the “Mr. Good Grips” line of kitchen utensils by OXO has been tested, first in the

laboratory and then in thousands of kitchens. Feedback on their performance can be obtained using

consumer suggestions and focus groups. Similarly, at the scale of an automobile, the Japanese have

made the most progress when it comes to universal design features. These can include ramps that

allow a wheelchair user to roll directly into the back of a van, or a driver’s seat that swivels and

allows the driver to enter and exit the vehicle more easily, especially when he or she has limited use

of the legs.

The above framework serves to illustrate the pervasive nature of universal design as it reaches

into virtually every aspect of our life space: at home, at work, or during travel to near and distant des-

tinations. Field-based research using real-world settings and actual users of UD items and features

will generate the basis for knowledge building in universal design performance. A case in point is

the controversy surrounding the use of Segways by persons with disabilities in indoor public spaces

(Watters, 2007a, 2007b), and so is the emerging trend to better accommodate persons with disabili-

ties in tourism, and the travel industry in general.

At this time the only guideposts for universal design assessments are the above-referenced

seven Principles of Universal Design (Story, 2001). The principles were created by the Center

of Universal Design at North Carolina State University and its consultants from throughout the

United States. The principles constitute lofty ideals, accompanied by subsets of guidelines and

design recommendations, which are rather general and not quantified at all. Thus, they are helpful

in pointing the designer into the right direction, but not adequate to let him or her know what to

do in a specific situation.

The challenge is to operationalize the seven principles and to align them with the type of per-

formance criteria standards and guidelines with which designers and planners are accustomed. For

Scale of UD Item Examples of UD Features Assessment Methods Assessment Measures

Fiskars scissors Left-handed use Time/motion study Ease of manipulation/

cutting speed

Appliances; e.g.,

washer/dryer

Left or right mounts Observation

Time/motion study

Verbal feedback

Ease of use

Interior Architecture Hard floors Time/motion study

Observation

Abrasion

Ease of movement

Buildings Wayfinding system Tracking of building users Ease of orientation/

speed of wayfinding

Urban environment Mixed-use vertical

integration

Transportation hub method

Time-lapse video/observation/

still photography

Ease of movement

Different conditions of

crowding

Information technology Global access to services

via the Internet

User feedback

Questionnaire survey

Satisfaction

Speed of access

Efficiency of services

TABLE 38.1 Universal Design Assessment Framework

TOWARD UNIVERSAL DESIGN PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENTS 38.3

example, fire codes clearly spell out the maximum distance from an occupied space to the legal fire

egress location. In staying with this example, various factors play a role in the establishment of such

criteria, such as type of occupancy, construction type, space sizes, and general layout considerations

(e.g., open versus closed/compartmentalized spaces), not to mention any hazardous conditions, such

as seismic or biohazards. In summary, the still-emerging field of universal design has a long way to

go before it can consider itself established, as far as building performance criteria and assessments

are concerned.

As is evident from this book and the multidisciplinary backgrounds of its contributors, a great

number of disciplines are affected by universal design. These range from planners and designers to

facility managers and groups that utilize facilities, especially health care and rehabilitation employ-

ees, as well as individuals dealing with all sorts of disabilities. Therapists and people studying human

behavior and interactions are involved, and so are administrators/managers of communities and

facilities that cater to seniors. Disciplines that are relevant to UD are listed in Table 38.2.

The building industry, especially housing (Preiser, 2006), is also beginning to take note of uni-

versal design by creating and building prototypes of universally designed houses, such as the home

built by the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) (2002) near Washington, D.C., and a

similar demonstration home by the IDEA Center by the University at Buffalo (Tauke and Schoell,

2010). The question arises whether assessments of these universally designed homes have been done

in a thorough manner, if at all, and whether the lessons that have been learned will be applied to

future generations of such homes.

Furthermore, information technology is a particularly fertile ground for exploring universal

design concepts. Just consider how the VISA card, perhaps the most universal of all universal

designs, has revolutionized the business world by permitting customers to carry out transactions in

several hundred countries with different banking systems and currencies. The VISA card provides

true universal access to merchants and services on a global basis (Hock, 2005).

38.3 EXAMPLES OF CULTURAL, LEGISLATIVE, AND

PROFESSIONAL ISSUES

Disability is conceptualized differently across various cultures, including diverse subcultures within

the United States. One example is the concept of “visitability,” which connotes the ability of a person

with disabilities to enter a place, but not necessarily to live in it (Nasar and Evans-Cowley, 2007).

TABLE 38.2 Universal Design—Relevant Disciplines

Discipline Examples of Universal Design Applications

Industrial Design See 3 sub-fields below

Product Design Utensils, tools, furniture, equipment

Graphic Design Directories and guidance systems

Fashion Design Clothing for various disabilities

Interior Design Accessible design of dwellings, offices and other spaces and places

Architecture Equal access and circulation for all user groups and levels of disabilities

Urban Design and Planning Accessible design of transportation facilities, university campuses and

communities in general

Information Technology Access to services and Internet commerce

Health Facilities Planners Accessible hospital, rehabilitation and care facilities

Administrators Enlightened governance regarding accessibility in organizations

Facility Managers Operation and maintenance in line with accessibility requirements

Environmental Psychologists Research in support of constituencies with disabilities

38.4 EDUCATION AND RESEARCH

Due to the lack of operational performance criteria, codification of universal design assessments

has not progressed enough. Ideally, UD assessments should relate to regulatory devices such as

building codes, but should also transcend the minimum requirements of the ADA. There are ethical

dilemmas and potential conflicts of interest and litigation in cases where universal design and its

potential are not achieved, e.g., in senior living communities. Segways (Watters, 2007a, 2007b) can

aid persons with disabilities in navigating through neighborhoods, shopping centers, and establish-

ments such as Barnes & Noble bookstores, but they can also create controversy in the business world

for safety reasons and fear of litigation.

Some tourist destinations and cruise lines improve accessibility for disabled persons (Craeger,

2007). For example, the Rocky Mountaineer Railtour from Vancouver, British Columbia, to Calgary,

Alberta, provides spectacular vistas of the Canadian Rockies. It features an elevator to lift wheel-

chair users to the top level of railcars. Near Newport, Oregon, at Yaquina Head Outstanding Natural

Area, wheelchair users can roll on paths around the tide pools at low tide. At Fantastic Caverns near

Springfield, Missouri, a tram “follows an ancient riverbed and gives visitors a great look at some of

the magnificent stalactite and stalagmite formations” (Harrington, 2008).

38.4 NEEDED ASSESSMENT METHODS—CREATING

A RESEARCH AGENDA

The goals of creating a universal design assessment research agenda are twofold: (1) To collaborate

with colleagues in the emerging field of universal design (called inclusive design or design for all in

Europe), in an effort to create a research agenda which will advance it to the next level of pragmatic

application in the real world; and (2) more specifically, to develop a tool kit of methodologies.

Tables 38.3 and 38.4 constitute the rather complex universe of data-gathering methods and mea-

sures. When they are utilized in a selective fashion, it is hoped that this will allow universal design

solutions to be evaluated in a systematic manner. Furthermore, this could support the creation of

performance criteria, which relate to regulatory mechanisms such as zoning and health and safety

codes. Functional requirements can be developed, as documented in design guides for different

building and space types. Finally, psychological and cultural needs of the users of universal design

can be distilled.

In adopting the field of human factors as a possible role model for evaluative research, it

becomes clear that a comprehensive universal design assessment framework implies a sophisticated,

multimethod approach. This would involve hard and quantitative as well as subjective and qualitative

measures with a focus on the human-environment interface. Furthermore, it would include field and

laboratory studies of spatial, physiological, psychological, and even cultural dimensions of universal

design.

For universal design to transcend its “soft” ideals and to be taken seriously in the pragmatic

world of planning, designing, and construction, a rigorous and accountable approach must be taken

in measuring and analyzing universal design performance. Just as in the precedent-based medical

diagnoses or legal determinations, universal design needs to move into the direction of “hard”

science and facts, Multiple medical diagnoses or legal precedents form the basis of acceptable

TABLE 38.3 An Overview of Data Gathering Methods and Measures

1. Behavioral Observations Behavior Inventory and Taxonomy

2. Mechanical Recordings Occupant and Environment Patterns

3. Visual Recordings Occupant and Environment Change

4. Physical Measurements Physical Measures

5. Verbal Response Measurement Perceived Performance Measures

6. Expert Judgment Point Ratings

TOWARD UNIVERSAL DESIGN PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENTS 38.5

TABLE 38.4 Detailed Data Gathering Methods and Measures

1. Behavioral Observations

Direct Observation

Participant Observation

Behavior Inventory and Taxonomy

• Behavioral Mapping

• Behavioral Identification/Classification

• Occupant Tracing

• Interaction Patterns/Dynamics

• Social Dynamics

• Utilization of Resources

2. Mechanical Recordings

• Counting

• Event Recording

• Light Sensor Gate/Contact Switch Plates

• Location Mapping

Occupant and Environment Patterns

• Frequency of Events

• Space Use

• Location of Occupants

• Use of Preferred Spaces/Resources

3. Visual Recordings

Still Photography

Video Recording

Time-Lapse Photography

Occupant and Environment Change

• Space Inventory

• Archival Records/Photo Annotation

• Ambient Environment Quality (Color, Light)

• Macro and Micro Behavior

• Occupant Movement

• Conflict Identification

• Behavior Sequences

• Occupant Speed/Tracking

• Individual vs. Group Interaction

4. Physical Measurements

• Gauge

• Chemical Test Kit

• Scale

• Light Meter

• Sound Meter

• Inclino-Meter

Physical Measures

• Temperature

• Humidity

• Air Velocity

• Light

• Chemical Agents

• Abrasion

• Elasticity

• Live-loads

• Decibels

• Light Levels

5. Verbal Response Measurement

Occupant Interviews

Occupant Surveys

Perceived Performance Measures

• Generic/Open-Ended Questions

• Forced Choice Questions

• Numeric Ratings

• Generic/Open-Ended Questions

• Forced Choice Questions

6. Expert Judgments

• Aesthetic Quality Comparisons

• Point Rating Systems

“truth” or evidence that has been proved in the real world. Medical therapy or legal fixes are predi-

cated on knowledge vetted in databases and clearinghouses that could specialize in types of products,

buildings, infrastructure, as well as information technology. As such, the author envisions three next

steps to progress in this endeavor:

1. Prior to the creation of a conceptual framework for universal design performance assessment,

there is the need for the development of a distinct and widely accepted terminology. An example