Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER 35

DIGITAL CONTENT FOR

INDIVIDUALS WITH

PRINT DISABILITIES

Charles Hitchcock

35.1 INTRODUCTION

A significant number of individuals with print disabilities find it difficult, if not impossible, to benefit

from information that is typically provided in print or in inaccessible digital formats. Limited access to

essential information required at home, school, and work can severely limit opportunities to function

and succeed in any environment where print is the primary medium for obtaining information (Rose

and Meyer, 2002). Individuals with print disabilities include those who are blind, have low vision,

have physical disabilities that prevent using standard print and books, and have reading disabilities due

to organic or physical causes. Although a variety of production and distribution systems for Braille,

large print, audio files, and e-text are now in place, timely preparation and delivery of such specialized

formats continues to be problematic. Students with print disabilities are not always identified by school

personnel, and even when they are, the delivery of specialized formats appropriate to their needs is

generally not provided in a timely manner, if at all. At the time of this writing, requirements for provid-

ing accessible formats for print have been enacted, but the infrastructure and technologies necessary to

deliver and use them have been slow to evolve. It is important to add that many of these students have

been supported with specialized formats available from the American Printing House for the Blind

(APH), Bookshare, and Recordings for the Blind and Dyslexic (RFB&D), along with services that

may be provided by individual states. This chapter provides background information on this topic and

current efforts to develop and deliver new tools and appropriate formats to support individuals with

print disabilities within elementary and secondary schools in the United States.

35.2 THE PROBLEM WITH PRINT AND PROGRESS

For individuals with print disabilities, print is a nonstarter. To make it usable, it is often scanned and then

converted to live text with optical character recognition (OCR) software so that it can be read with a

screen reader or other technologies that facilitate conversion of the text to audible speech. Scanning can

be tedious and time-consuming, involving significant resources due to duplication of effort, with many

scanned versions being created by many teachers and others—and this duplication occurs throughout

the world. Print is inflexible and cannot be easily modified to suit the needs of individuals.

For educational publishers, print is generally not the best outcome for a creative work flow.

Localized demand for textbooks aligned to state learning standards often requires additional time

35.1

35.2 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

and expense for content customization. Although demand for digital versions is growing, most print

editing tools are generally not optimal for generating custom versions and varied formats.

A solution to this problem has begun to emerge. Some publishers are now employing Extensible

Markup Language (XML) to create source files and are finding that, with appropriate markup, they

can deliver multiple electronic, print, and embossed formats as end products, all from a single source

file. Such an approach has the advantage of reducing duplication of effort and providing the flexibil-

ity needed to generate accessible HTML, DAISY Digital Talking Books, Braille, large print, audio

books, and traditional print. Although these specialized formats could be produced and sold by an

educational publisher, access to XML source files makes it possible for third-party accessible media

producers (AMPs) to develop accessible instructional materials (when allowed by current copyright

exemptions implemented to support individuals with print disabilities). Some publishers have begun

to realize that a market is growing for accessible alternate formats and are developing versions for

sale along with or in place of inaccessible print versions.

New standards are emerging that make it possible for software and services to use common

source files from different publishers to create specialized formats from publisher-developed XML

source files. The National Instructional Materials Accessibility Standard (NIMAS), based on the

international DAISY standard, is one such endeavor (Fig. 35.1)

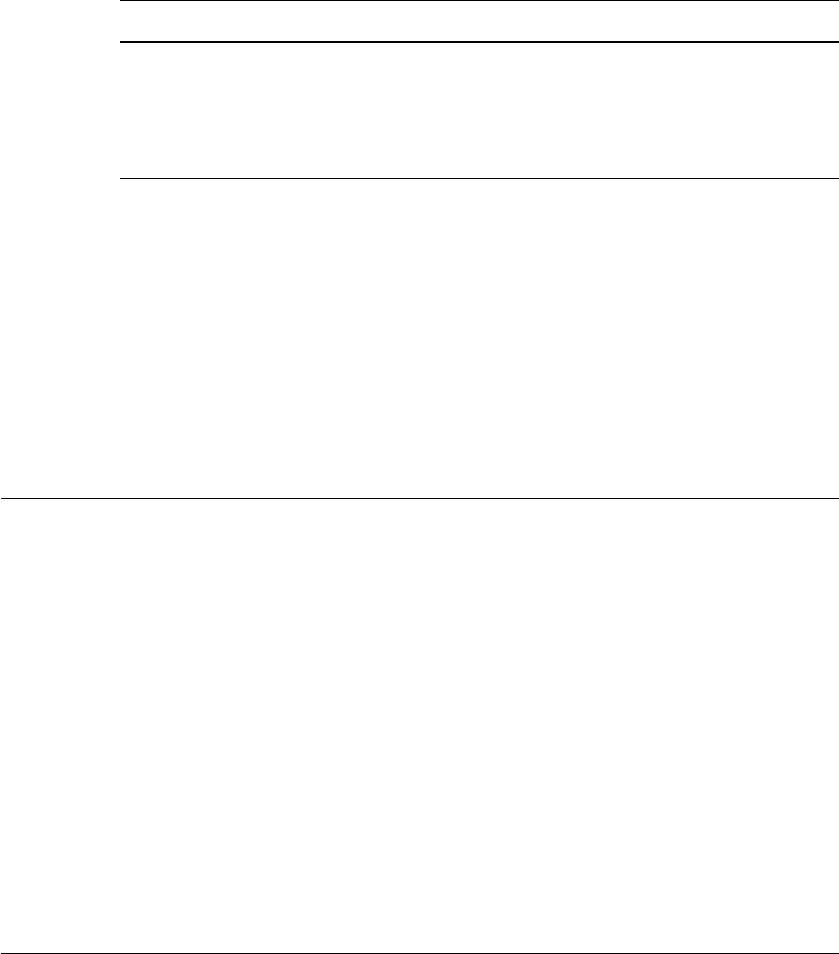

FIGURE 35.1 Low-resolution PDF version of NIMAS HTML created by the open-source NIMAS Conversion Tool.

Long description: Image of page 2 of the All About Coyotes UDL Editions Book converted from a NIMAS file set to

an HTML version. The image shows the title as Section, a link to the table of contents, navigation links for previous

and next pages, and a photo of a coyote standing in the grass. Text below the image reads, “Although coyotes can live in

just about any climate, they are mostly found in areas with open grasslands and low elevations. They tend to stay within

10 to 12 miles of their den. When food is scarce, coyotes will travel well beyond this range.” The bottom of the image

shows previous and next navigation links with the names of those sections.

DIGITAL CONTENT FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH PRINT DISABILITIES 35.3

35.3 BACKGROUND

The Act to Provide Books for the Adult Blind dates to 1931 (Pratt-Smoot, Chap. 400. Sec. 1, 46 Stat.

1487, 1931). It has since been amended to include children and those with physical and reading disabili-

ties. More recently, the Chafee Amendment of 1996 was enacted to enable authorized entities to prepare

and distribute specialized formats without obtaining permission from the copyright holders (Copyright

Law Amendment [H.R. 3754]; P.L. 104-197, 1996). It refers to the amended Act to Provide Books for

the Adult Blind to define the population who may benefit from Braille, audio, and e-text specialized

formats. Those that qualify include individuals who are blind, have low vision, or have physical or

reading disabilities due to organic dysfunction. Guidelines are provided by the National Library Service

(NLS), a division of the Library of Congress within the United States, to indicate who may certify each

population (Nail-Chiwetalu, 2000).

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA) of 2004 added large print to

the allowed specialized formats and also required state education agencies (SEAs) to adopt the NIMAS

and to indicate whether they planned to coordinate with a national database established to validate

and store NIMAS file sets. Whether they do or not, states are required to assure the U.S. Department

of Education that appropriate accessible instructional materials will be provided to students who are

served by IDEA and have print disabilities. IDEA 2004 also established the National Instructional

Materials Access Center (NIMAC) at APH so that authorized users and AMPs have access to high-

quality XML source files provided by educational publishers. An emerging problem is that not all

students with print disabilities have an individualized educational plan (IEP) under IDEA, and those

students may not qualify for specialized formats created with NIMAS file sets. For those students,

local scanning with OCR software may still be necessary until educational publishers are able to sell

specialized formats directly to local education agencies (LEAs).

35.4 A NEW APPROACH

A NIMAS file set is comprised of four components. It includes an XML file of the complete text-

book marked up using the NIMAS specification. It also includes all the images of the textbook

provided in one or more of three specified formats at a resolution of 300 dots per inch (dpi). It

also includes a package file that contains metadata about the textbook along with a complete

manifest of the file set’s contents. Finally, it includes a PDF of the textbook’s title page(s)

(or wherever copyright information is provided) for reference purposes (NIMAS Technical

Specification v1.1, 2006). Note that the NIMAS requirements apply primarily to textbooks and

core related instructional materials (such as workbooks and blackline masters). In some cases,

this may also include supplementary reading materials that accompany the textbooks when they

are sold to schools.

Ideally, publishers would establish an XML production work flow that produces a NIMAS

file set as a part of the production process as a textbook is on its way to becoming a high-

quality, print-ready PDF file. Such a production process would also allow for the development

of, e.g., HTML versions for sale alongside or in place of print versions. It is strongly recom-

mended that HTML versions, whether provided via the Internet or on CD-ROM, be developed

in compliance with the W3C’s Web Access Initiative (WAI) Content Guidelines so that these

versions may be rendered by a variety of browsers and be usable with a wide range of assistive

technologies.

At the time of this writing, most publishers deliver files in a variety of formats to third-party

conversion houses to produce NIMAS file sets under contract. Although an XML work flow

is not generally how most publishers work at this time, it is relatively safe to predict that it

will become fairly common as production and markup tools become easier to use in the years

ahead.

35.4 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

35.5 ASSISTIVE TECHNOLOGIES AND

NEW DEVELOPMENT TOOLS

Both commercial and open-source XML authoring tools are now available to any publishers that wish

to prepare their own NIMAS XML source files. Since these authoring tools reference an appropriate

document type definition (DTD) such as the one developed for DAISY digital talking books, valida-

tion of the files is relatively easy to obtain. Once consistent and valid source files are available in

XML, it is relatively easy to transform such source content into specialized formats with available

technologies. High-quality conversions are now possible with both commercial and open-source

transformation tools.

Staying with HTML as an example format, once a source file is converted to HTML and enhanced

by an AMP to comply with WAI Content Guidelines, textbooks may be viewed in, navigated with,

and spoken by modern assistive technologies. The same applies to Braille-ready files, audio files,

text files, and DAISY digital books. Some of the newer reading software available to students with

print disabilities supports multiple file formats and even performs conversions from one format to

another to provide for individual preferences and needs. HTML and DAISY versions generally also

include images that have been reduced from 300 to 72 dpi resolution for on-screen use. NIMAS file

sets may also be used to generate large print and are likely to include large images in the original

300 dpi resolution. Testing with available 300 dpi images is also underway to see if they might be

suitable for creating tactile graphics.

35.6 POLICY, STATUTE, REGULATIONS, AND GUIDELINES

Much progress has been made over the past few decades with respect to improving learning oppor-

tunities for learners with print disabilities. The concept of print disabilities evolved in part from the

1931 Act to Provide Books to the Adult Blind and was refined by means of various amendments to

the act that shaped services provided by the NLS.

In 1975, Public Law 94-142, known as the Education for All Handicapped Children Act,

became law and supported states and districts in protecting rights of access to education for all

students with disabilities. The law provided important rights to students and families and required

that local education agencies identify and serve students with disabilities, guided by an IEP. In

1990, the reauthorization of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act was renamed the

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), and, with minor amendments, passed in

1991. It emphasized a free and appropriate education within the least restrictive environment for

students with disabilities (Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; enacted 1975; amended

1997 and 2004).

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act provided a foundation for the concept of a civil right to

access materials in higher education in 1973 (Rehabilitation Act; Section 504). Universities extended

services to support students with disabilities, and eventually this included adapting instructional

materials to provide access for students unable to use print (Hall and Stahl, 2006). Only recently

was language included in the Higher Education Act to address the needs of students with print dis-

abilities. Although it should apply to K–12 education as well, Section 504 services are generally

offered to support students with disabilities that do not require an individualized education plan

under IDEA.

The 1990 passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act did not generally improve the

availability of accessible instructional materials. Although it is often referenced with regard

to housing and workplace accommodations, only recently has it been used effectively to argue

for the accessibility of information on the World Wide Web, as exemplified by the class action

settlement between the National Federation for the Blind and Target.com (Case No. C 06-01802

MHP, 2008).

Until the passage of Public Law 104-197 in 1996, usually referred to as the Chafee

Amendment, the preparation and distribution of specialized formats were dependent upon the

DIGITAL CONTENT FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH PRINT DISABILITIES 35.5

cooperation of authors and publishers who granted NLS and others permission to reproduce

copyrighted works without royalty. Authorized entities, as defined by the Chafee Amendment,

could now produce and deliver specialized formats to students who qualified by means of the

amended 1931 Act. This permissions process often created delays in providing specialized for-

mats to those who qualified.

In 1998, amendments to Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 included specific

requirements regarding the accessibility of federal government and contracted web sites, software,

telecommunications, technology, and office devices. The U.S. Access Board developed a stream-

lined version of the W3C WAI Web Content Guidelines (WCAG) to support federal government

sites and products. WCAG and Section 508 have provided important guidance for the development

of accessible HTML used in schools and higher education over the past decade.

The 2004 reauthorization of IDEA included the NIMAS and created the NIMAC at APH. The

NIMAS language was designed to address the national need to increase the availability and timely

delivery of appropriate instructional materials in accessible formats to blind or other students with

print disabilities in elementary and secondary schools. NIMAS established a new technical standard

for publishers to use in producing electronic versions of all their textbooks sold for use in U.S.

public schools. As noted earlier in this chapter, those electronic versions (called NIMAS source

files) are highly flexible and can be used to develop many different specialized formats such as

Braille; large print; HTML versions; DAISY talking books, using human voice or text-to-speech;

and audio versions.

One source of confusion regarding the NIMAS is how best to support students who do not

qualify for NIMAS-derived instructional materials. The original regulations did not actually

define what a print disability is, but instead specified the types of individuals who would qualify

as print-disabled: those who are blind, those with a specified degree of low vision, and those

certified by a competent authority as unable to read printed material in a normal manner because

of physical limitations or organic dysfunction. This definition has persisted and remains part of

the NIMAS legislation. The IDEA regulations associated with the statute require that all students

with an IEP who require accessible instructional materials be provided with appropriate special-

ized formats in a timely manner. This has proved problematic for states and local school districts

that are not able to benefit from the efficiencies of NIMAS. Some have resorted to scanning their

own instructional materials and/or attempting to purchase accessible materials directly from edu-

cational publishers.

35.7 UNIVERSAL DESIGN OF TEXTBOOKS

Ideally, local school districts, colleges and universities, and states would not have to worry about the

source of specialized formats. The best possible outcome for many would be the option to purchase

accessible formats directly from educational publishers. We have only begun to see the emergence of

a “market model” for such instructional materials and look forward to a time when that is an option

available to all learners. Such an approach requires that the publisher purchase the electronic rights

to all the included text and images, and this has proved to be both difficult and expensive in the past.

It is becoming more common, in the negotiation of newer contracts with copyright holders, and a

limited number of products are beginning to emerge.

It seems unlikely that publishers will consider the market for Braille and large print sizable

enough to develop and sell such formats, but providing a combination of print, HTML on CD-ROM

or via the Internet, DAISY digital talking books, and audio books does appear to be feasible, and

such products are likely to be purchased by schools and students on the basis of both personal pref-

erence and needs. The universal design of textbooks seems close at hand, and it is quite likely that

publishers will use their own NIMAS file sets to develop specialized formats.

Examples of NIMAS file sets and various accessible digital instructional materials created

with existing conversion tools (see Fig. 35.2) can be viewed at the NIMAS Technical Assistance

web site.

35.6 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

35.8 UNIVERSAL DESIGN FOR LEARNING AND TEXTBOOKS

Accessible instructional materials provide an important foundation, but many educators question if

this is adequate to meet the critical learning needs of our diverse student population. An accessible

digital HTML textbook, e.g., may feature live text that can be read with text-to-speech; may feature

a font that can be modified with regard to size; may be easily navigated by chapter, section, or page

number; may have images supported by alternative text and long descriptions when appropriate; may

have math equations provided as images with alternate text or, even better, as MathML; and may

have content order, levels, and headings determined by publisher tagging. Digital agents that can be

incorporated into HTML versions have been developed as well to provide important hints and models.

This would make an HTML textbook reasonably accessible to available assistive technologies.

A key question is whether accessible is good enough for an education environment where learning

and improved outcomes are the primary objectives. The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST)

has furthered our thinking about this matter by developing guidelines to support universal design for

learning (UDL) for educational settings (Rose et al., 2005). They include a baseline of accessibility

features and promote the inclusion of key scaffolds and supports that enhance learning. Although they

are intended to apply to a full range of educational goals, instructional materials, teaching strategies,

and assessments, the focus here is primarily on what can be accomplished with instructional materials.

A few examples of learner supports that exemplify UDL might include a table of contents with links

to appropriate locations within the body of the text, vocabulary supports with links to a contextual-

ized glossary, comprehension supports such as prompts and scaffolds for applying reading strategies,

optional highlighting of critical features and big ideas, opportunities to interact with the core content

and embedded prompts at varied levels, and hints and models to support responding.

CAST has developed exemplars for such features within an assortment of literacy-oriented mate-

rials and has made them freely available on the Internet as models (Fig. 35.3). At the time of this

writing, many are featured on the Google Literacy Project web site as part of UDL Editions and are

directly available from CAST’s server.

35.9 CONCLUSION

This discussion emphasizes that accessible and appropriate instructional materials are critical to

the success of students with print disabilities. Universally designed media are also proving to be of

similar benefit for recreational reading and for productive work. Much progress is being made by

FIGURE 35.2 Low-resolution PDF version of sample NIMAS XML from All About Coyotes.

Long description: This image shows a portion of XML code marking up content according to the NIMAS technical

specification. The code reads as follows:

DIGITAL CONTENT FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH PRINT DISABILITIES 35.7

means of standards such as DAISY and NIMAS (a subset of DAISY), but much remains to be done.

Publishers need to produce and sell accessible content for individuals with print disabilities and

those with other needs and preferences. Using audio-based alternate formats as an example, such

needs might include listening while walking or as a passenger in a bus or car, reading or listening in

environments with reduced light, focusing attention with highlighted text while listening to a human-

voice narration or a text-to-speech conversion, and listening to varied content at slower or more rapid

rates. All this is possible today.

It is important to continue to research and implement the types of supports promoted by univer-

sal design for learning (Rose et al., 2005). Only then will it be practical to suggest that the playing

field has been leveled with regard to access and learning performance. Early phase exemplars have

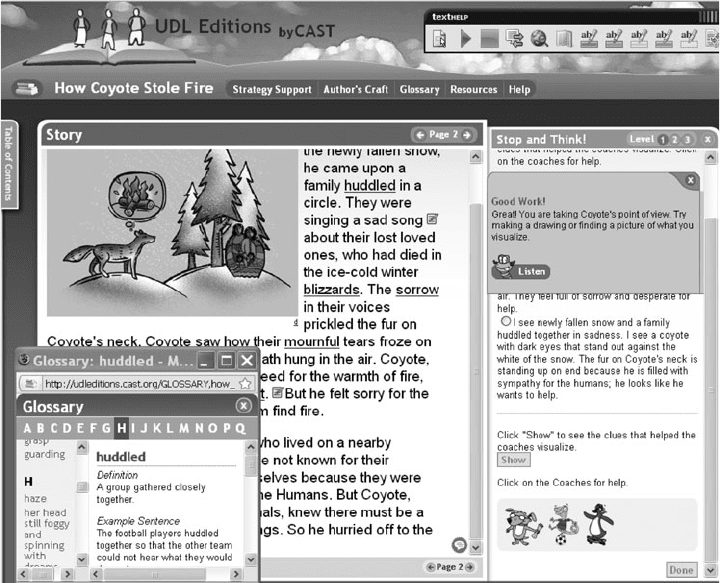

FIGURE 35.3 Low-resolution PDF version of How Coyote Stole Fire, a CAST UDL Edition.

Long description: This screen shot shows an HTML page of the CAST UDL Editions book selection entitled How

Coyote Stole Fire. The top of the page shows a logo that is an illustration of three humanlike figures standing on an open

book, followed by the heading “UDL Editions by CAST.”

On the top right is a toolbar offering text-to-speech and highlighting features.

On the navigation bar below this, the book’s title and links to book features are shown. Features are Strategy Support,

Author’s Craft, Glossary, Resources, and Help.

In the main window below the navigation bar the story is displayed. On the left is a tab to open the book’s table of

contents. The upper left shows a picture of a coyote thinking about fire and looking over the hills toward pine trees and

a family of Native Americans. The story text is shown on the right and underneath the picture and includes key words

that are linked to a glossary.

A glossary window is open at the bottom left of the screen, showing the word huddled and its definition and a sample

sentence. On the right side of the screen an open Stop and Think window is shown with buttons for three levels of sup-

port. A response window is open, indicating that a correct response was provided. Three digital agents or coaches are

shown at the bottom right.

35.8 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

been developed and made freely available for replication, and it should soon be possible to say that

individual differences within a diverse learning and work population will be both respected and

valued.

35.10 BIBLIOGRAPHY

An Act to Provide Books for the Adult Blind (Pratt-Smoot); Chap. 400. Sec. 1, 46 Stat. 1487; 71st Congress.

Approved, Mar. 3, 1931. Accessed from http://www.loc.gov/nls/act1931.html on Mar. 2, 2009.

Case No. C 06-01802 MHP; U.S. District Court; Northern District of California; Class Action; Class Settlement

Agreement and Release. [National Federation of the Blind; the National Federation of the Blind of California,

Bruce F. Sexton, Jr., Melissa Williamson, James P. Marks (on behalf of those named and all others similarly

situated), Plaintiffs; vs. Target Corporation, Defendant.] August 2008. See http://www.nfbtargetlawsuit.com/

final_settlement.html.

Copyright Law Amendment (H.R. 3754); PL 104-197; 104th Congress. Approved Sept. 16, 1996. Accessed from

http://www.loc.gov/nls/reference/factsheets/copyright.html on Mar. 2, 2009.

Hall, T. E., and S. Stahl, S., “Using Universal Design for Learning to Expand Access to Higher Education,“ in

Inclusive Learning in Higher Education, M. Adams and S. Brown (eds.), London: RoutledgeFalmer, 2006.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act; enacted 1975; amended 1997; amended 2004. See http://idea

.ed.gov/explore/home.

Nail-Chiwetalu, B., “Guidelines for Accessing Alternative Format Educational Materials,” 2000, accessed from

National Library Service, http://www.loc.gov/nls/guidelines.htm, on Mar. 2, 2009.

NIMAS Technical Specification v1.1; part of National Instructional Materials Accessibility Standard; Final

Rule. Federal Register, vol. 71, no. 138; Rules and Regulations, Department of Education, 34 CFR Part 300;

RIN 1820–AB56; Wednesday, July 19, 2006. Accessed from http://www.ed.gov/legislation/FedRegister/

finrule/2006-3/071906a.html on Mar. 2, 2009.

Public Law 94-142—Education of All Handicapped Children Act, now Individuals with Disabilities Education

Act; enacted 1975. See http://www.ed.gov/policy/speced/leg/idea/history.html.

Rehabilitation Act; Sec. 504; Nondiscrimination under Federal Grants and Programs. See http://www.section508

.gov/index.cfm?FuseAction=Content&ID=15.

Rose, D. H., and A. Meyer, Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning,

Alexandria, Va.: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2002.

———, ———, and C. Hitchcock, The Universally Designed Classroom: Accessible Curriculum and Digital

Technologies, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Education Press, 2005.

35.11 RESOURCES

American Printing House for the Blind (APH); http://www.aph.org.

Americans with Disability Act

http://www.ada.gov

Bookshare

http://www.bookshare.org

CAST UDL Editions

http://udleditions.cast.org

CAST UDL Guidelines

http://www.cast.org/publications/UDLguidelines/version1.html

Chafee Amendment

http://www.loc.gov/nls/reference/factsheets/copyright.html

DAISY Consortium

http://www.daisy.org

DIGITAL CONTENT FOR INDIVIDUALS WITH PRINT DISABILITIES 35.9

Google Literacy Projects

http://www.google.com/literacy/projects.html

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (2004)

http://idea.ed.gov

http://frwebgate.access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname=108_cong_public_laws&docid=f:publ446.108

National Library Service FAQ

http://www.loc.gov/nls/faq.html

NIMAS Conversion Tool

http://aim.cast.org/experience/technologies/nimas_conversion_tool

NIMAS Development and Technical Assistance centers’ web site

http://aim.cast.org

NIMAS/NIMAC Glossary

http://aim.cast.org/glossary

NIMAS Technical Standard

http://aim.cast.org/learn/policy/federal/spec-v1_1_anno

Recordings for the Blind and Dyslexic (RFB&D)

http://www.rfbd.org

Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Title V, Sections 504 and 508)

http://www.access-board.gov/enforcement/Rehab-Act-text/title5.htm

W3C Web Accessibility Initiative

http://www.w3.org/WAI