Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER 28

DIVERSITY AND EQUALITY

IN HOUSING: DESIGNING

THE ARKANSAS PROTO-HOUSE

Korydon H. Smith

28.1 INTRODUCTION

Diversity and equality are apparent antonyms, yet both are valued in today’s political and social

climates and in contemporary design discourses. However, reconciling the inevitability of diversity

and the obligation of equality is no small feat. The question remains as to how civil equality can

be achieved as society becomes more diverse. How can housing both meet the variety of needs and

preferences of a society and ensure equity among the various groups that comprise that society? Can

equity be achieved in spite of the disparities; can equitable housing and neighborhoods be developed

despite local economic and sociological imbalances?

Although these questions are universal, they are, perhaps, most salient in the American South.

The South, and places such as Arkansas, is defined as much by mythology as by its divisive history:

stark racial and economic rifts and inversely a warm climate, warm food, and warm hospitality. The

reconciliation of diversity and equity is a prime marker in the physical and political landscape of

the South. The South, rather unexpectedly, therefore, serves as a testing ground for universal design

(UD). As such, the goal of this chapter is to explore how UD ideals can be applied in particular

social and physical contexts. This occurs through the development of the Arkansas Proto-House.

The overarching goal is to explore the common ground between diversity and equality, between the

universal and the specific, in contemporary housing design.

28.2 DIVERSITY AND ARKANSAS

Many lessons have been learned in recent years, as universal design concepts have proliferated

worldwide. Arkansas, however, is an unlikely place to look for lessons in good design. In fact, it

may be the last place Americans look for counsel about anything. Arkansas is more likely to be the

punch line of any number of “trailer trash” jokes than an exemplar of good housing practices. But

as English Prof. Fred Hobson (2005) states, “The South always makes good reading. It features the

virtues and vices, writ large, of the nation as a whole.” From a broad perspective, Arkansas is often

stereotyped as rural, poor, and unrefined. In a closer look at each region of the state, many of these

stereotypes are upheld; some are not. An even finer view reveals a great deal of economic, educa-

tional, racial, topographic, and climatic diversity within the state.

28.1

28.2 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

Historically, political boundaries—between countries, states, locales, etc.—were often coincident

with geologic, topographic, or other natural features, such as rivers, mountains, etc. Cultural migra-

tion, advancements in military and transportation technologies, and developments in commerce,

however, have diminished the magnitude of these natural features. Many newly established political

jurisdictions—especially local jurisdictions—operate independent of identifiable geographic figures

and boundaries. The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, for instance, shifted the flow pattern of the

river, resulting in discrepancies between the state boundaries of Arkansas and Mississippi relative to

the river. There are now oddities where parts of Arkansas (or parts of Mississippi) are “on the other

side of the river.”

Many states throughout the United States are defined by shifts in geological or landscape pat-

terns, e.g., the border between Ohio and Kentucky. Yet other borders are merely circumstantial,

geometric superimpositions upon an otherwise unmarked landscape, such as that of Colorado

and Wyoming. Arkansas, not unlike Tennessee, North Carolina, and others, possesses both

naturally defined borders, such as the Mississippi River to the east, and surveyed borders, such

as the northern border between Arkansas and Missouri. The Land Ordinance Act of 1785 and

the Jeffersonian grid established 1-mi

2

plots of land, which were superimposed on the existing

natural features of the West and Midwest. What resulted, as evident in a states map of the United

States, was a hybrid condition, where both the Jeffersonian grid and natural features work in

tandem to define political boundaries. Sociological, economic, climatic, and topographic char-

acteristics, however, are not homogeneous throughout any state or country. Differences between

urban and rural, flat and mountainous, temperate and extreme exist within any given political

or legal boundary. So, although Arkansas maintains the highest poverty rate and third highest

rate of disability in the United States, poverty and disability are not evenly distributed. Neither

is employment, nor is access to health services, public education, and suitable housing. This is

common throughout the world.

The eastern part of Arkansas, “the Delta,” is predominantly agricultural, is flat and prone to flood,

and maintains a much greater prevalence of poverty and disability than the rest of the state. In com-

parison, the northwestern part of the state, the Ozark Plateau, has both pockets of economic vibrancy

and impoverishment. While Benton and Washington counties comprise one of the 10 fastest-growing

economies in the United States and are home to the largest company in the world, Wal-Mart, the nearby

counties of Newton and Searcy, respectively, have 20.4 and 23.8 percent of individuals in poverty,

according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The third major geographic region of Arkansas, the West Gulf

Coastal Plain of the southwest, is predominantly rural and wooded, maintains poverty and disability

rates higher than the national average, and relies on manufacturing for much of its employment.

Given this sociological, economic, environmental, and technological diversity, it is difficult to

imagine the design of a singular prototype that accommodates these variations. Nonetheless, an

economy of means through standardization is essential to providing high-quality, affordable hous-

ing. Pure customization is not viable. In addition, overarching housing policies set forth by state

legislatures need to be applied at the local level. Housing prototypes, therefore, need to adhere to

state policies and industry standards, while simultaneously, creating a physical and a psychological

“sense of home” for individuals. As famed country singer and Arkansan Johnny Cash (1997) stated,

it was essential to have “a place where I knew I could belong.”

28.3 DESIGN CRITERIA AND PATTERNING OF THE ARKANSAS

PROTO-HOUSE

Many factors influence the decisions people make about buying or renting a home, including loca-

tion, cost, family structures and needs, and aesthetics. While the housing industry and popular

culture tend to place emphasis on the fourth item—“looks”—the first three play a greater role in

selecting a residence, e.g., proximity to work, school, and/or family, especially among less affluent

rural Southerners. While Sec. 28.4 explores issues regarding site specificity, this section investigates

the role that cost and family size/structure play in housing, in addition to overarching principles of

design and construction.

DIVERSITY AND EQUALITY IN HOUSING: DESIGNING THE ARKANSAS PROTO-HOUSE 28.3

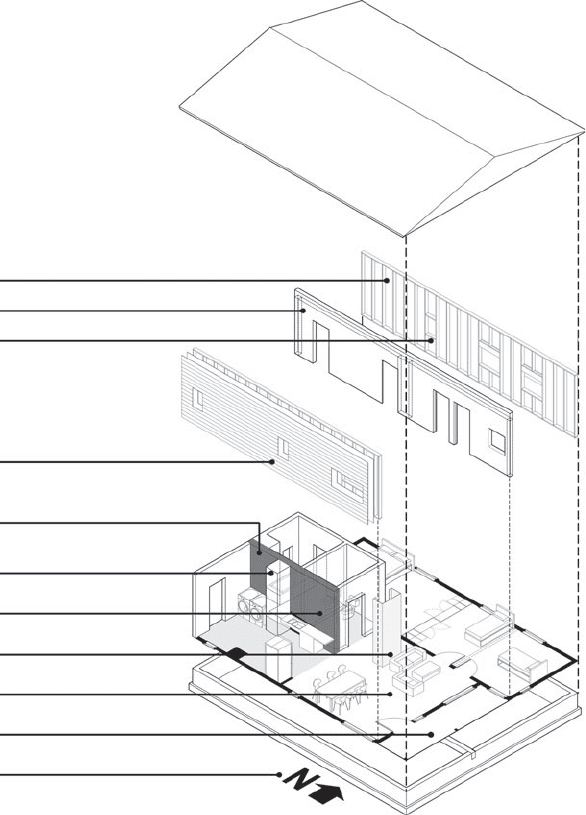

First, design criteria were developed by analyzing Arkansas’ diverse geologic, environmental,

cultural, and economic characteristics as well as understanding the strong correlation between

poverty and disability in the South. Eleven major principles, under the auspices of two overarching

concepts—maximizing adaptability and maximizing efficiency—resulted (see Fig. 28.1).

Size structural members for material efficiency

Minimize interior load-bearing walls

Utilize modular construction

Utilize durable, low maintenance

materials & assemblies

Use continuous structural surfaces

in bathrooms & kitchens

Size HVAC systems for

energy efficiency

Cluster plumbing &

electrical utilities

Utilize adaptable cabinetry,

fixtures, & furniture

Utilize open-space

planning

Ensure ease of mobility,

operability, perceptibility, & security

Site building for energy efficiency &

community integration

FIGURE 28.1 Maximizing adaptability and maximizing efficiency were the two overarching

principles of the Arkansas Proto-House.

Long description: The axonometric diagram illustrates five design principles to maximize adapt-

ability: (1) minimize interior load-bearing walls; (2) construct continuous structural surfaces in bath-

rooms and kitchens; (3) utilize easily adapted cabinetry, fixtures, and furniture; (4) utilize open-space

planning and minimize space used exclusively as circulation; and (5) ensure ease of mobility, operability,

perceptibility, and security for diverse users. The diagram also illustrates six principles for maximizing

efficiency: (1) utilize modular construction, (2) cluster utilities together, (3) size structural members for

material efficiency, (4) size HVAC systems for energy efficiency, (5) site building for energy efficiency

and community integration, and (6) utilize durable, low-maintenance materials and assemblies.

28.4 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

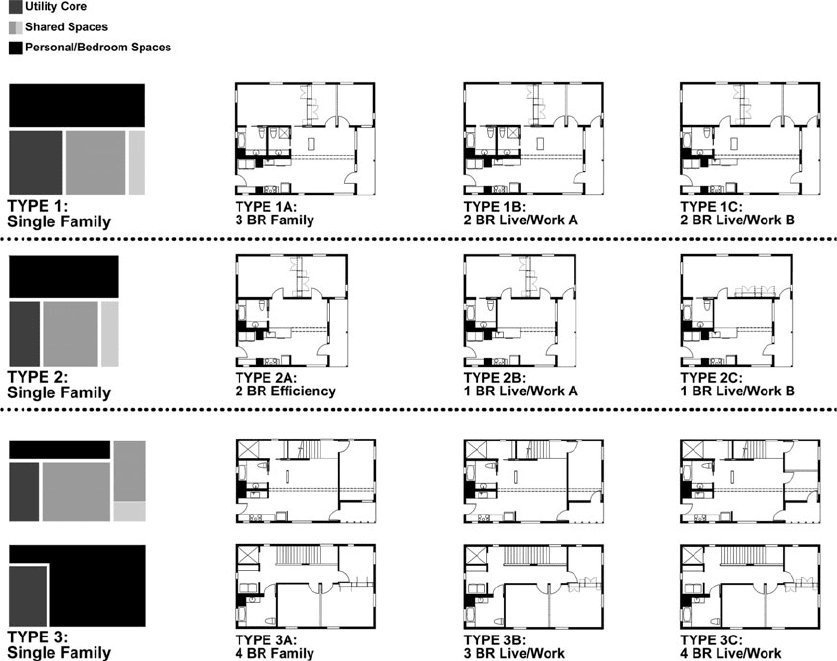

Second, these design criteria led to the general design of the Arkansas Proto-House through a

patterning of nine single-family types (see Fig. 28.2). This taxonomy included three major types:

(1) a one-story family, (2) a one-story efficiency, and (3) a two-story family. Each major type included

a range of three subtypes, including one family option and two live/work options. The family options

centered on sleeping and family gathering spaces, while the live/work option included a home office

accessible from the main porch entry and was able to be closed off to the rest of the home. The

common features of all types included (1) a fully accessible ground floor, including access to living,

eating, food preparation, bathing and toileting, and sleeping spaces; (2) a fully accessible porch,

providing exterior living space and mediation between the public and private realms; (3) interior

circulation enabling movement for diverse occupants or visitors; and (4) fixtures, e.g., door hardware,

sink fixtures, etc., easily operable by diverse occupants and visitors.

It is a common practice among developers and homebuilders to establish a set of major typologies

and a set of subtypes and options. Rather than negate this convention, the Arkansas Proto-House was

developed such that the underlying principles, organization, and structure of the various Arkansas

Proto-Houses are the same, facilitating a more efficient approach to urban, suburban, and rural housing

FIGURE 28.2 A framework of typologies comprises the Arkansas Proto-House.

Long description: The plan diagrams illustrate the three major typologies of the Arkansas Proto-House: (1) a one-story family, (2) a one-

story efficiency, and (3) a two-story family. The diagrams also show a range of three subtypes for each typology, including one family option

and two live/work options.

DIVERSITY AND EQUALITY IN HOUSING: DESIGNING THE ARKANSAS PROTO-HOUSE 28.5

developments. It is, however, the subtle differences and transformability of the types that accommodate

diverse family structures and disparate topographic, sociological, and climatic contexts.

28.4 DEPLOYING THE ARKANSAS PROTO-HOUSE

Clients, designers, developers, and builders negotiate a vast number of factors in the design and con-

struction of housing, including sociological, technological, economic, environmental, and legal factors.

All these factors include micro-, meso-, and macro-scale issues, which are often interrelated. The hierar-

chy of these issues may change greatly from one project to the next, as clients, sites, and material costs

change. Although issues such as material costs or personal preferences greatly influence housing design,

construction, and purchasing decisions, often site-based issues exert the greatest demands and limita-

tions. Site factors include topography, orientation to the street, orientation to the sun, and parking.

The tendency in many single-family developments and tract housing schemes is to eliminate or

ignore these features by flattening topography, ignoring the cardinal directions, and dogmatically

repeating the housing across the landscape, resulting in increased site costs, increased heating and

cooling costs, and decreased neighbor and community interactions. The generic Arkansas Proto-House,

on the other hand, was modified by these four factors. The approach, threshold space and porch, and

interior organization of each prototype were transformed to create a better fit and increased usability.

The major design challenges and strategies employed are demonstrated in each localized case study

discussed below. The goal is to illustrate how the aforementioned taxonomy of types might accommo-

date diverse sites and diverse household structures, while maintaining a certain degree of universality.

More specifically, one exemplar was designed for each of the three regions of Arkansas previ-

ously discussed—the Ozark Plateau, the West Gulf Coastal Plain, and the Mississippi Alluvial

Plain—demonstrating how the general prototypes might be deployed within a given context. In each

of these regions, lots were identified in three cities: Fayetteville, Hot Springs, and Arkansas City.

These lots were chosen primarily for the design challenges that they presented, and they served to

test how effectively the Arkansas Proto-House could be transformed to the idiosyncrasies of a given

site. “Site-specific” design is important. According to Reed (1972), “Southerners seem to have

retained a greater degree than other Americans a localistic orientation—an attachment to their place

and their people. Although there are some cracks in this pattern, localism can be expected to color

the outlook of many Southerners for some time to come.”

In addition, each of these case studies—the Ozark prototype, the Ouachita prototype, and the

Delta prototype—demonstrated circumstances that were prevalent not only in that given region but

also throughout Arkansas and the South. As such, each resulting prototype is more typological than

regional; each prototype maintains the possibility to be deployed in similar circumstances elsewhere.

Although the prototype designs focused on the house proper, relationships to the surrounding infra-

structure, natural landscape, and community were essential.

Ozark Prototype

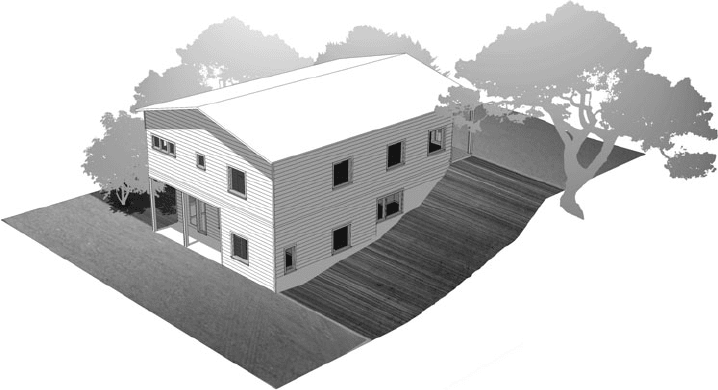

The first site selected was in Fayetteville, a diverse college town in the Ozark region of the state. The

site possessed numerous challenges. The site had a triangular lot with two adjoining streets, it was

steeply sloping, and it sat on the border between commercial and residential zones. Type 1A (family)

and type 1B (live/work) were utilized to create a stacked duplex. Duplex housing is quite prevalent in

the area, but typically possesses two major shortcomings. First, it is often conceived of as two inde-

pendent houses “merged at the hip,” and not as an integrated whole. Second, parking, approach, and

privacy between the units are seldom well resolved. The Ozark case study, conversely, is conceived

as a whole unit and from the street appears as one large single-family home. This strategy enables

the residence to appear more substantial and helps to combat the “not in my backyard” attitude often

confronted in affordable housing. In addition, the Ozark prototype has two “fronts.” The lower level

faces a prominent main street, while the upper level faces a side street, although both are accessible

28.6 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

at grade due to the topography. The lower-level, live/work unit faces the commercial zone and uti-

lizes an on-site parking strategy, whereas the upper-level, family unit faces the residential zone and

takes advantage of on-street parking (see Fig. 28.3).

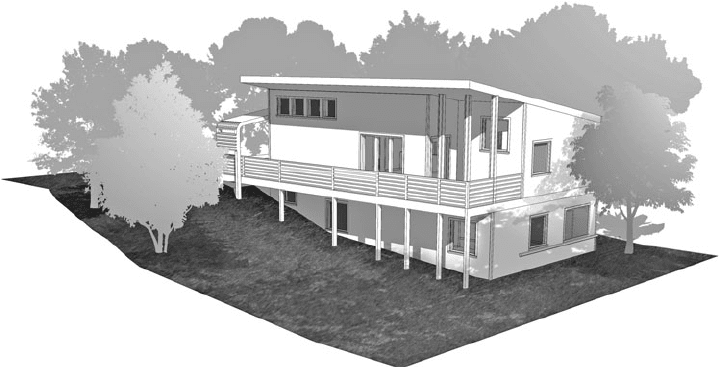

Ouachita Prototype

The second site selected was in Hot Springs, a retreat town in the Ouachita region of the state. The

site was steeply sloping; it sat amid an older residential neighborhood on a very narrow lot; it had

no access on the primary public street due to a 6-ft-high retaining wall between the sidewalk and the

property line; and it could only be accessed by a narrow dead-end alley. Homes typically marketed as

“accessible” or “elder-friendly” are often one-level, but owing to the narrowness of the lot, a single

level was not possible. The two-story type 3A (family) unit was used.

Most two-story homes follow a fairly standard organization, where the lower, or “ground,” level

contains the more public functions of living, dining, and food preparation, while the upper level

houses sleeping and bathing spaces. The Ouachita prototype is a transformation of this standard

typology. As the Ouachita is accessed by a rear alley on the high side of the property, the first and

second levels are inverted in comparison to the norm. The top level is accessed at grade and contains

living, dining, and food preparation spaces, in addition to one bedroom and one full bathroom. The

lower level contains three additional bedrooms and another full bathroom. This house may not be

defined as “universal,” but it is “inclusive” to most families. While disability rates are incredibly high

in Arkansas, families that have two or more people with mobility impairments are relatively rare.

This home, because of the design of the fully functioning upper level, therefore, accommodates the

needs of most families. In addition, the stair is wider than a conventional stair and is “straight-run.”

This design better enables assistance in ascending and descending or the future installation of a lift.

The structural framing is also designed to easily accommodate the future installation of a residential

FIGURE 28.3 This two-level duplex contains an accessible live/work unit on the lower level, which faces the com-

mercial district, and an accessible family unit on the upper level, which faces the residential district.

Long description: The aerial rendering of the Ozark prototype shows the two-level duplex, highlighting the accessible

live/work unit on the lower level, which faces the commercial district.

DIVERSITY AND EQUALITY IN HOUSING: DESIGNING THE ARKANSAS PROTO-HOUSE 28.7

elevator, if the homeowner so chooses. Despite the small footprint, the open plan, cathedral ceiling,

and large glazing allow the interior to appear spacious. The Ouachita prototype also possesses a

wrap-around porch that provides exterior living space, entry, and a “front face” to the public street

(see Fig. 28.4).

Delta Prototype

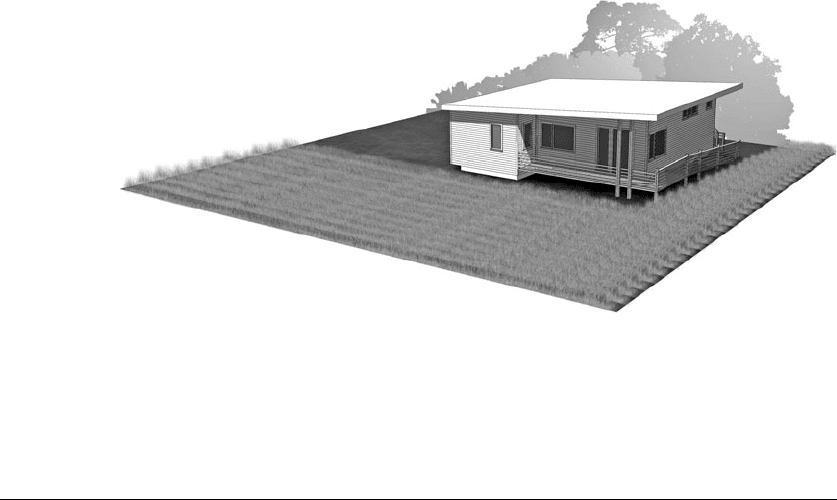

The third site selected was in Arkansas City, a historic Mississippi River port town in the Alluvial

Plain. The site was flat, prone to flood, hot and humid, and it was located on a fairly visible corner

lot. Steeply sloping sites are often considered to be the most challenging for accessibility and the

least desirable to many developers. This may be a bit of an oversight, however, as slopes can be

used advantageously, like those of the Ozark and Ouachita prototypes. The biggest challenge to

inclusive housing design in the Delta is the flatness of the landscape and its propensity to flood.

This requires that homes be raised several feet above grade. So, how can entry and exit be accom-

modated efficiently without steps? In some cases, the surrounding land can be graded to slope up

to the house. Typically, however, this is prohibitively expensive, and ad hoc ramp solutions often

are the result.

Due to these factors and the prevalence of single-parent and single-resident households and high

rates of poverty in the Delta, the type 2A (efficiency) was chosen. The home was raised 3 ft above

the surrounding land, and a porch was provided. The porch was designed to wrap around the corner

and transform into an integrated ramp. From the street, only the porch is visible. The porch also

provides exterior living space and protection from the sun. The open floor plan facilitates ventilation

and allows the interior to seem more spacious. The home is accessible from a rear parking area, from

which an occupant or visitor can ascend the ramp/porch to the main living space or move directly

into the kitchen via a small set of steps (see Fig. 28.5).

FIGURE 28.4 This two-level single-family home contains an upper level with sleeping, cooking, dining, bathing, and

living spaces and a lower level with additional sleeping spaces. The upper level connects to rear parking via a wrap-

around porch.

Long description: The aerial rendering of the Ouachita prototype shows the two-level single-family home, highlighting

the wrap-around porch, which overlooks the neighborhood below.

28.8 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

28.5 CONCLUSION

As housing production has slowed, health care costs have risen, and demographics make massive

shifts, the United States confronts a tremendous question: How can housing (1) meet the variety

of needs and preferences of society, (2) ensure equity among the various groups that comprise that

society, and (3) be created at low cost and high quality? Nowhere is this question more pertinent,

timely, and challenging than in Arkansas and the South, a region characterized by strong contrasts in

economic, racial, geographic, educational, and health statuses, not to mention the political mythol-

ogy of the “segregated South.”

The Arkansas Proto-House is an attempt to address the varied economic, sociological, envi-

ronmental, and technological conditions of the South. These residences tackle the challenge of

developing prototypes that are both replicable and culture- and site-specific. Like so many univer-

sally designed homes, all versions of the Arkansas Proto-House contain kitchens, bathrooms, and

living spaces that accommodate the needs of a wide range of families and individuals. Likewise, all

examples address economic issues by maximizing material and environmental efficiencies.

The Arkansas Proto-House is an exploration in meeting the physical and psychosocial housing

needs of the state, as well as an analogue for solving parallel concerns across the South, the United

States, and the world. For example, one of the greatest challenges to attainable housing in areas

experiencing economic and housing booms, such as northwest Arkansas, is the rapid rise in land

values. Increased land costs push affordable housing to the outskirts of town, increasing the distance

inhabitants must travel to access employment, education, health care, and amenities. The Ozark ver-

sion of the Arkansas Proto-House takes advantage of a site that is typically considered “unbuildable”

due to slope and zoning—a site that is centrally located, yet vacant. Each example illustrates how a

“standardized” prototype can be deployed in a “custom” setting. The Arkansas Proto-House seeks to

work within the diverse social and physical contexts of the South without pandering to stereotypes.

Its design features are not exclamatory; this is a central value of universal design, or, quite simply,

good design. The Arkansas Proto-House demonstrates how the universal becomes specific, how

diversity results in equity.

FIGURE 28.5 This one level efficiency unit is augmented by exterior living space and rural surroundings.

Long description: The aerial rendering of the Delta prototype shows the one-level efficiency home, highlighting the

wrap-around porch, which serves as exterior living space and a transition into the home.

DIVERSITY AND EQUALITY IN HOUSING: DESIGNING THE ARKANSAS PROTO-HOUSE 28.9

28.6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cash, J., Cash: The Autobiography, New York: Harper-Collins, 1997, p. 193.

Hobson, F., quotation from USADeepSouth.com, Winter 2005; http://usadeepsouth.ms11.net/winter05.html.

Reed, J., The Enduring South: Subcultural Persistence in Mass Society, Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Heath & Co.,

1972, p. 43.

28.7 RESOURCES

Arkansas Proto-House, Studio for Adaptable and Inclusive Design, www.studioaid.org.