Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

26.10 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

• The family room bench/hearth is at an accessible height.

• There is a handheld remote control unit for lights and all audio/video equipment.

Library

• The accessible workstations have adjustable keyboards at positions that allow frontal-

approach knee and toe clearance.

• The cabinet hardware is accessible.

• The lateral fi le drawers are within easy reach of seated people.

• The meeting table is easily moved and provides wheelchair-accessible knee and toe

clearance.

Third Floor

Laundry

• The fl oors are nonslip waterproof stained concrete.

• The roll-in shower features a hand held shower, grab bars,and shower seat.

• The shower curtain hangs on a hinged bar.

• The sauna controls are accessible.

• The sauna door and bench are accessible.

• The clothes washer and dryer are front-loading.

• The sink features a front-mounted lever faucet.

• The grab bar doubles as a towel rail.

• The towel rods and clothes pegs are mounted at an accessible height.

• The base cabinet features an oversized toe space and accessible drying rack.

Master Bedroom

• There is a 3-ft-wide space on both sides of the bed.

• There is a no-threshold accessible door that leads to the accessible rear deck/emergency exit.

• The height of the clothes storage is adjustable.

Master Bath

• The fl oor is made of waterproof nonskid concrete.

• The shower features a no-threshold entry at wheelchair width with a self-closing,

double-swinging glass door.

• The heights of the handheld showerheads and deluge shower are adjustable.

• The shower and sink faucet hardware are accessible.

• The cabinet hardware is accessible.

• The side-access toilet and bidet are integrated into one unit.

• The accessible-height refrigerator drawers can store fresh fruit, cold water, and medications.

• There are full-height mirrors on the pocket doors.

26.6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

National Consortium of Housing Research Centers, Lifewise House, Annual Report, 2004; www.housingresearch.net.

Salmen, J., “Proposed Definition,” The Future of Universal Design Meeting, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta,

GA, June 26, 2006; http://futureofud.wikispaces.com/Proposed+Definition+%28Salmen%29. Accessed May 3, 2010.

Universal Design Newsletter. published quarterly by Universal Designers & Consultants, Inc., Takoma Park, MD.

20912; www.UniversalDesign.com.

Universal Design Online: www.UniversalDesign.com.

CHAPTER 27

THE SENSORY HOUSE

Beth Tauke and David Schoell

Architecture is the art of reconciliation between ourselves and the world, and this mediation

takes place through the senses.

Juhani Pallasmaa (2005)

27.1 INTRODUCTION

Given that senses change significantly throughout people’s lives, it follows that carefully balanced,

multisensory home environments might increase both physical and psychological well-being.

Architects are beginning to focus on new sensory strategies that establish greater reciprocity between

the home and its occupants.

Attention to multisensorial experience parallels the introduction of inclusive design paradigms

to the broader architectural discourse. While inclusive practices have generated tremendous benefits

in terms of facilitating physical access, still underrecognized is the potential benefit of expanding

universal design to more fully engage sensory issues.

27.2 SENSE SYSTEMS

Traditional sensory classification has five commonly referenced modalities: vision, hearing, smell,

taste, and touch. Although medical fields still adhere to this system, a model presented by Gibson

(1966) has proved more conducive to design applications: (1) visual system, (2) auditory system,

(3) taste-smell system, (4) basic orienting system, and (5) haptic system. This model considers space

as a more integral component of sensory perception. Each system has its own spatial component as

well as a spatial relation to the other sense systems. While Gibson’s model includes the traditional

senses, it introduces an expanded categorization of sensory perception, a foundation upon which new

design strategies may be discovered, tested, evaluated, and employed.

27.3 THE VISUAL SYSTEM

The visual system typically is regarded as the primary means to acquire information about an envi-

ronment. Vision works using a refractory system (the eye) that focuses light waves onto nerve end-

ings, which communicate with the brain for interpretation.

Visual processing is not just a simple translation; instead, the image that is transferred to the

retina requires complex interpretation to result in what one “sees.” Because eyes see forms in light,

Gibson (1966) asserts that “vision is useful for (1) detecting the layout of the surrounding, (2) detecting

27.1

27.2 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

changes, and (3) detecting and controlling locomotion.” Vision is considered to have the greatest

precision for perceiving space and the environment at a distance. As such, it plays a primary role in

basic human survival.

Despite the current overuse of and dependence on the visual realm, attention to its application in

the home offers advantages that both improve function and enhance pleasure. For example, various

lighting types and levels provide enriched visual access. (see Fig. 27.1).

Clearly differentiating edges using lighting and color contrast helps those with low vision or those

operating in low lighting conditions to better understand their environment. Light also has the potential

to prompt directional cues. Illuminating the end of a hallway can have a leading or pulling effect.

Light affects physical and psychological senses of well-being. Several studies have demonstrated

that a shortage of exposure to daylight or artificial bright light has been linked to the occurrence

of mood and behavior shifts. Indoor illumination that compensates for seasonal low light levels is

beneficial to a sizable portion of the population (Grimaldi et al., 2008). Therefore, consideration of

lighting levels and timing helps to balance these shifts.

As a component of both light and material, color also affects the understanding of and response

to domestic space. Used sensitively, color can enhance safety (i.e., contrasting colors on stair tread

edges), increase attention span, stimulate appetite, influence emotion, and change perception of

spatial form (see Fig. 27.2).

The interaction of light and material is a source of aesthetic pleasure. People “find beauty not

only in the thing itself but in the pattern of the shadows, the light and dark which that thing provides”

(Tanizaki, 1991). It is this relationship that moves the visual out of its culturally commodified role

and into one where humans become participants in this interplay.

FIGURE 27.1 While most homes have two to three lighting sources per habitable space, the

LIFEhouse, an inclusively designed home in the outskirts of Chicago, provides a minimum of

five lighting conditions in each room. Kitchen lighting includes daylighting, overhead, under-

cabinet, over-cabinet, shelf illumination, and task lighting in the appliances. Controls are on

dimmers, allowing the resident maximum control of the ways that the space is lit. (Photograph

© 2009 Susanne Tauke.)

Long description: This photo of the LIFEhouse interior by New American Homes shows a

kitchen area with multiple modes of lighting: daylighting, overhead, under-cabinet, over-cabinet,

shelf illumination, and task lighting in the appliances. Those working in the kitchen area are able

to choose between a variety of lighting options to meet specific needs.

THE SENSORY HOUSE 27.3

27.4 THE AUDITORY SYSTEM

The auditory system responds to vibrations and is mechanical in nature. “The ears receive sounds

and send them to the auditory cortex, near the back of the brain, for processing” (Anissimov, n.d.).

Hearing is an active process. While humans cannot physically shut out sound, they do have the

ability to focus on what they want to hear. Therefore, the basic purpose of hearing is not merely to

detect sound, but instead to “pick up the direction of an event, permitting orientation to it, and the

nature of the event, permitting identification of it. Its proprioceptive function is to register the sounds

made by the individual, especially in vocalizing” (Gibson, 1966). These basic survival tasks involve

distance, orientation, spatial understanding; the relation between the self and the world (physiologi-

cally and psychologically); and social interaction.

As such, the auditory system has remarkable potential for spatial definition. The reverberation

of sound describes the confines, expanses, and materials in space. Apart from helping to cognitively

sculpt the spatial confines of a volume, sound also can assist navigation. Humans have the ability to

“transform the acoustic attributes of objects and geometries into a useful three-dimensional internal

image of an external space. . . . Listeners who must move around in places without light are likely

to . . . recognize open doors, nearby walls, and local obstacles” (Blesser and Salter, 2007).

Typically, aural architects and sound engineers focus on the design of concert halls, restaurants,

and other public spaces in which sound is a primary programmatic component. No less important is

the design of sound in the home, which can (1) provide escape from sound pollution, (2) establish

zones of privacy and socialization, (3) give warnings, and (4) enhance sound pleasure.

Designing spaces in the home where people can experience quiet is becoming more important as

noise levels from the outside world increase. There are well-established techniques for noise-abating

designs that include reducing sound reverberation time, limiting airborne noise, reducing impact

noise, and minimizing background noise (Gatland, n.d.). Architects can employ sound-absorbing

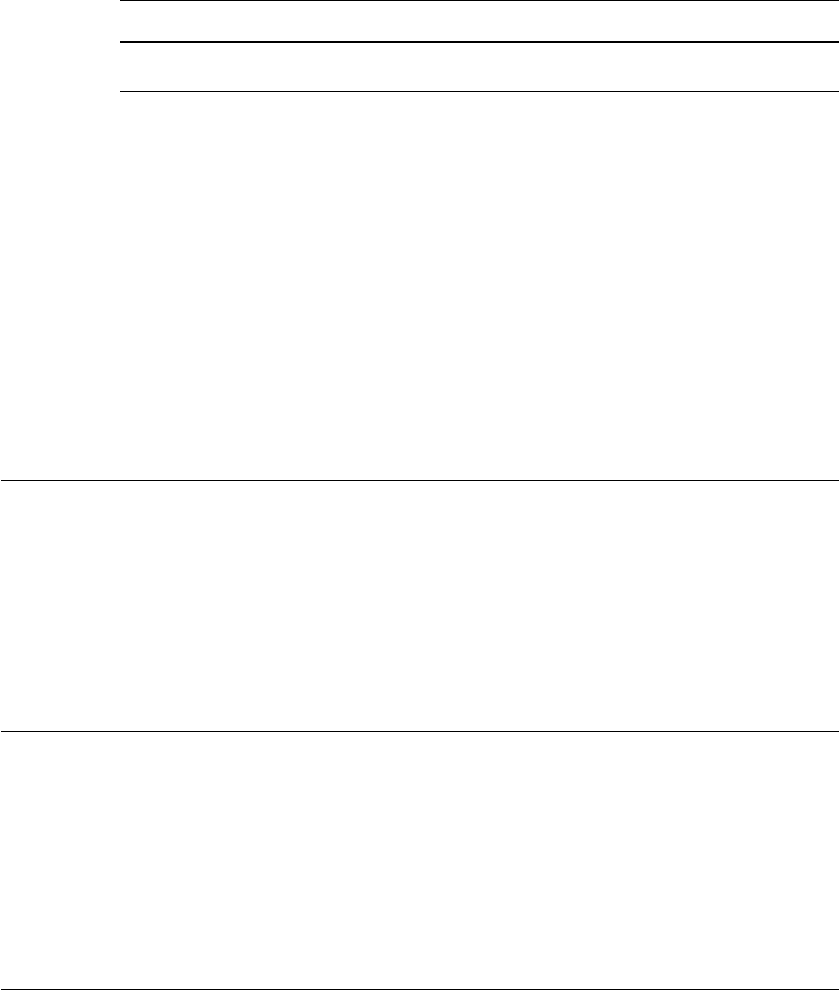

FIGURE 27.2 In Louis Barragan’s Casa Gilardi in Mexico City, brilliant red

and blue pigments on vertical surfaces were used to invoke a simultaneous sense

of “presence” and immateriality in the indoor pool area to prepare residents for

the act of swimming. (Photograph © 2007 Adolfo Peña-Iguarán.)

Long description: The photo shows an indoor pool area at Louis Barragan’s

Casa Gilardi in Mexico City. A square skylight illuminating one area of the

pool suggests a cubic volume. Two joining walls of the skylit area are painted

a brilliant blue. A third separated, bright red wall connects the skylight and the

pool.

27.4 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

surfaces, such as fabrics, carpeting, acoustical materials, and natural vegetation; add sound-absorbing

insulation to wall and ceiling cavities; and install solid wood or mineral core doors with threshold

closures in spaces designed for quietness.

Most homes have places for socialization as well as privacy that require attention to acoustic

design. Places of socialization are first and foremost places of listening, and they require high levels

of sound absorption. High reverberation in these areas does not invite relaxed conversation, and it is

particularly frustrating to those with hearing difficulties. Essential considerations for effective sound

design include room dimensions and shape, position of furniture in relation to the shape of the space,

placement and types of openings, and construction techniques. Adding conversation niches or spaces

in overly large social spaces provides hearing-friendly areas that allow greater participation and thus

more inclusion.

Warning and alert systems such as smoke alarms, burglar alarms, and stove timers are typically

sound-based. Of primary importance is the sound range of these devices. The human ear is most

sensitive to frequencies around 1,000 to 3,000 Hz (Cutnell and Johnson, 1998). As a result, it is criti-

cal that all alarms cover this frequency range. In addition, alarms that are sound-based should offer

other sensory prompts such as light, color, smell, and/or movement shifts.

When considering the aural palettes of homes, designers might move beyond sound reduction,

isolation, and absorption and into positive acoustic design as well (Schafer, 1977). Designers might

not only consider the physical and spatial support system to ensure sound quality, but also consult

with occupants to ensure choices and levels that are both stimulating and enjoyable.

27.5 THE TASTE-SMELL SYSTEM

Given that taste and smell operate together, they often are regarded as “alternative ways to experi-

ence similar phenomena” (Molnar and Vodvarka, 2004). Approximately 75 percent of what is per-

ceived as taste is derived from the sense of smell. Taste-smell is a chemical sensing system and is

activated when “molecules released by the substances around us stimulate nerve cells in the nose,

mouth, or throat” (American Academy of Otolaryngology, n.d.).

As survival mechanisms, taste and smell stimulate the desire to eat and warn of various dan-

gers in the environment such as fire, poisonous fumes, and spoiled food (American Academy of

Otolaryngology, n.d.). In addition, the taste-smell system affects preferences and aversions and,

as such, influences emotion and behavior. Strong correlations have been found between smell and

attention, reaction times, mood, and emotional state. Taste-smell can stimulate the memorization of

concepts or experiences, and acts as a contextual retrieval cue not only for autobiographic memories

but also for other types of memory, including visual-spatial memories (Gutierrez et al., 2008).

Taste-smell as a spatial definer is often neglected by designers. “Odors lend character to objects

and places, making them distinctive, easier to identify and remember” (Tuan, 1977). Each home, like

each person, garners an individual scent. Materials such as wood and masonry characterize space

with their odors. Others, such as textiles, fabrics, and draperies, absorb the odors of inhabitation.

Occupants’ actions can determine the scent of each room, and consequently the scent suggests what

behaviors are typical in various spaces of the home. In this way, the scent of the space and the scent

of the person merge.

This unique condition provides many opportunities to use the taste-smell system not only to

define space, but also to enhance everyday living conditions. Attention to material selection can

identify various spaces with specific scents. For instance, rooms might be surfaced with odiferous

materials such as rosewood or odor-reflecting materials such as porcelain. Smell might be used as

an intuitive layer in home safety warning systems; alarms could emit odors as well as sounds to alert

those who otherwise would not connect a sound with a warning. Circulation systems can be designed

to bring outdoor scents into interior spaces (see Fig. 27.3).

Smell is linked to and strongly influences parts of the brain that deal with emotion (Harnett,

n.d.). For example, the smell of baking bread might give a sense of comfort. Scents known to reduce

stress, such as chamomile, might be introduced into rooms designed for resting. Rooms designated

THE SENSORY HOUSE 27.5

for productivity might contain materials such as cypress that have been demonstrated to increase

alertness. To be effective in concert, however, the design of taste-smell systems in the home requires

precision and restraint; overload cancels the positives.

Perhaps more important is the flexibility of taste-smell design elements to accommodate those

with sensitivities. Air filtration and cleaning systems become an essential component of home

design that allows occupants to control airflow and purification and, therefore, the type and level of

odor contained in their living spaces. In addition, dangers detected by smell, such as gas leaks and

fire, need supplemental warning systems that engage other senses. More than other sense systems,

the inclusive design of the taste-smell system in the domestic setting is challenging because of its

pervading nature. Rather than avoiding it altogether, designers might focus on innovations that offer

adaptability and contain the infusion of taste-smell in ways that help us to enjoy its many benefits.

27.6 THE BASIC ORIENTING SYSTEM

The basic orienting system uses (1) the vestibular system (balance), (2) orientation (position in

space), (3) kinesthesia and proprioception (position of the body parts), and (4) the boundary of the

skin (where the outside world begins) to “place” the constantly changing person in a constantly

changing environment. This system works with the other sense systems to establish a three-dimensional

experience of space. Kinesthetic sensations begin with vestibular organs as equilibrium of posture

is balanced with gravity. During this process, humans subconsciously define edges and contours of

solids and reveal options for movement (Gibson, 1966).

Reed (1996) stresses the significance of the basic orienting system: “Without this basic ability to

adjust one’s body and its parts to the surroundings, literally nothing else could happen.” This system

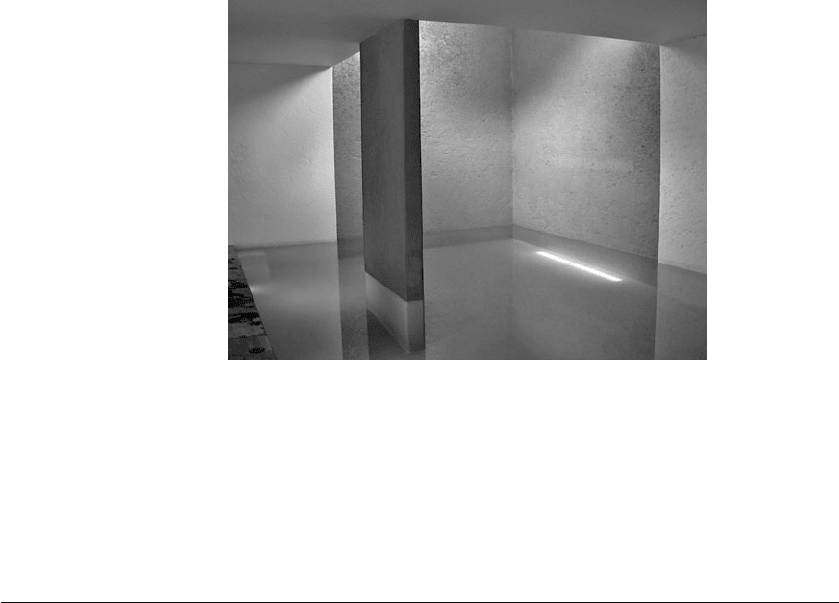

FIGURE 27.3 The Simpson-Lee House in Mount Wilson, New South Wales, Australia, by

architect Glen Murcutt has siting and interior circulation systems assisted by sliding windows

that are designed to allow the scent of exterior elements to waft through the house when weather

permits. (Photograph © 2008 Kyle Briscoe.)

Long description: This photo shows the Simpson-Lee House by architect Glenn Murcutt. A

wood-slat ramp leads to a covered entrance and establishes circulation in the interior straight

through the house. A large slanted roof shades a two-square transparent façade. Next to the

exterior ramp is a rainwater storage area.

27.6 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

allows “the detection of the stable permanent framework of the environment” (Gibson, 1966). It

plays a primary role in survival by establishing (1) a sense of gravity and the supporting surface (the

ground), (2) the distinction between sky above and earth or water below (the horizon), (3) the loca-

tion of events and objects in the environment, (4) oriented locomotion or finding one’s way toward a

goal, and (5) geographical orientation, where way-finding occurs over long distances.

Incorporating the basic orienting system in home design involves the establishment of reference

points for occupants. For example, the home entrance is a key way-finding marker. Possible entrance

accentuation strategies include positioning it on axis, using a change of material, incorporating a

canopy or marquee, creating emphasis with landscape features, etc. (see Fig. 27.4).

Also important is the reciprocal relationship between inside and outside. For example, windows

might be placed such that they mark the horizon line or positions of the sun. Air passages could be situ-

ated so that the sounds of front (e.g., traffic or street noise) and back (e.g., rustling trees) remind those

inside of the way the house is sited. Often underestimated, basic orientation is a core means to instilling

a sense of stability. It is the primary mediating device between humans and their environments.

27.7 THE HAPTIC SYSTEM

The haptic system “refers to our sense of touch extended to include temperature, pain, pressure, and

kinesthesia (body sensation and muscle movement). It is thus a system in which human beings are

literally in contact with their environment” (Gibson, 1966). The haptic system allows people to feel

objects, surfaces, and air/water quality relative to the body and, reciprocally, the body relative to

these features in the environment (see Fig. 27.5).

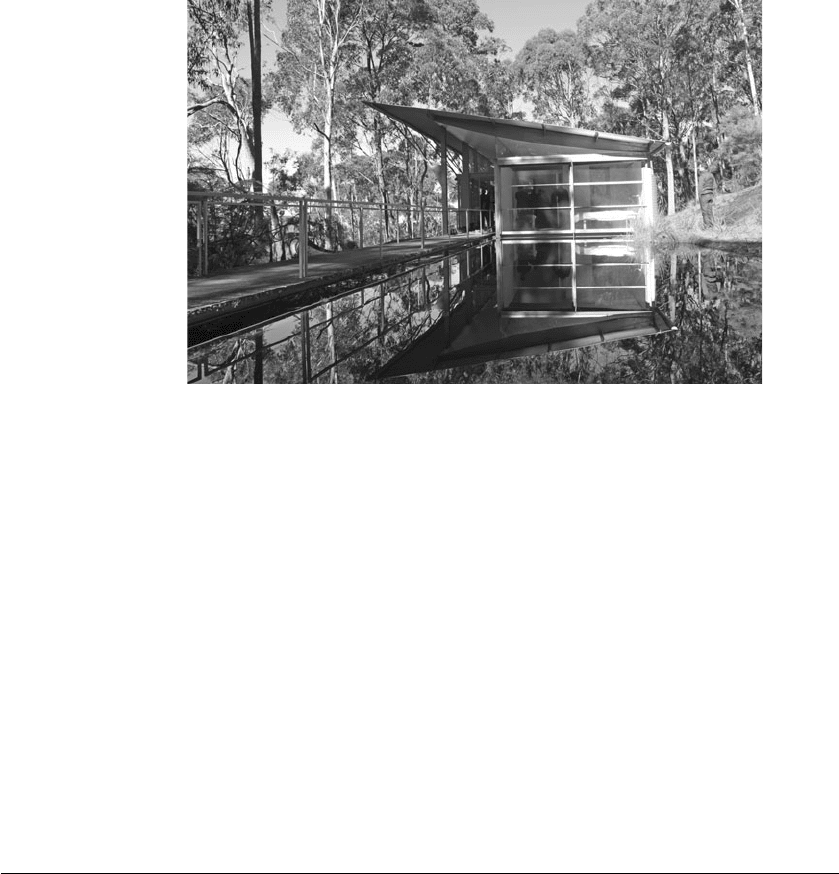

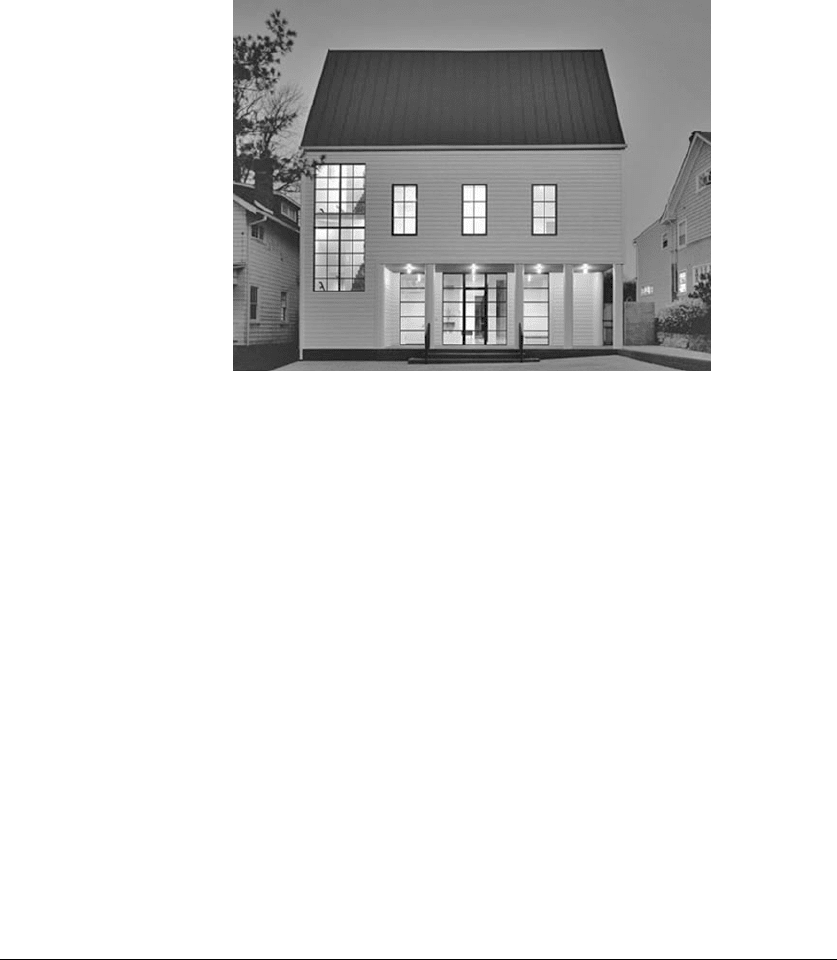

FIGURE 27.4 In the universally designed Kessler Residence, architect Robert

M. Gurney, FAIA, accentuates the entrance by means of a columned porch with

a bright red ceiling and a large glass door flanked by floor-to-ceiling windows.

(Photograph © 2004 Maxwell MacKenzie.)

Long description: This photo shows the front façade of the Kessler Residence

by Robert M. Gurney, FAIA, at dusk. The saltbox-shaped house is white with a

black roof. A large two-story gridded window reveals interior vertical circula-

tion on the left. Three rectangular six-paned windows light the second floor. The

front entrance is a one story cutaway that forms a columned porch with a bright

red ceiling and a large glass door flanked by floor-to-ceiling windows.

THE SENSORY HOUSE 27.7

The application of tactile strategies to residential architecture can characterize space, especially

for those with varying perceptive capabilities. For example, the hard edges of concrete create rigidly

defined spaces, whereas the flexibility of latex suggests greater ambiguity. Moreover, the tactility

of materials is indicative of certain activities. Sleeping spaces, for instance, typically contain softer,

warmer materials, suggesting places of rest. Kitchen surfaces might be harder, evoking places for

food preparation and cleanup. Hall (1969) notes that, especially in contemporary Western culture,

the “texture of surfaces on and within buildings seldom reflects conscious decisions; thus our . . .

environment provides few opportunities to build a kinesthetic repertoire of spatial experiences.”

Inclusive practices promote attention to the haptic system, and this is especially meaningful

in the home. Rethinking the domestic environment to elevate its tactile qualities supports a wider

population and provides richer information about their living environments. For example, changes in

floor textures can identify various spaces, establishing a subtle yet effective map of the home. Floor

temperatures can be regulated to provide seasonal balance—warmer during winter months; cooler in

the summer. Wall surfaces can be designed to interact with the body (see Fig. 27.6).

Handrails can be textured to indicate beginnings and endings. Surfaces that come in contact with

the body can be made safer: shower floors might be made of slip-free surfaces; faucet handles might

indicate safe levels of hot and cold. Exploring the potential of the haptic system within the home

allows for both grounding and extending the self through touch.

27.8 INTERDEPENDENT AND INCLUSIVE SENSORY SYSTEMS

The experience of architecture involves all the senses. Despite the longevity of this, “only a few stud-

ies have explored the way in which multisensory architecture influences the inhabitants of a space”

(Blesser and Salter, 2007). While technological advances have “ordered and separated our senses”

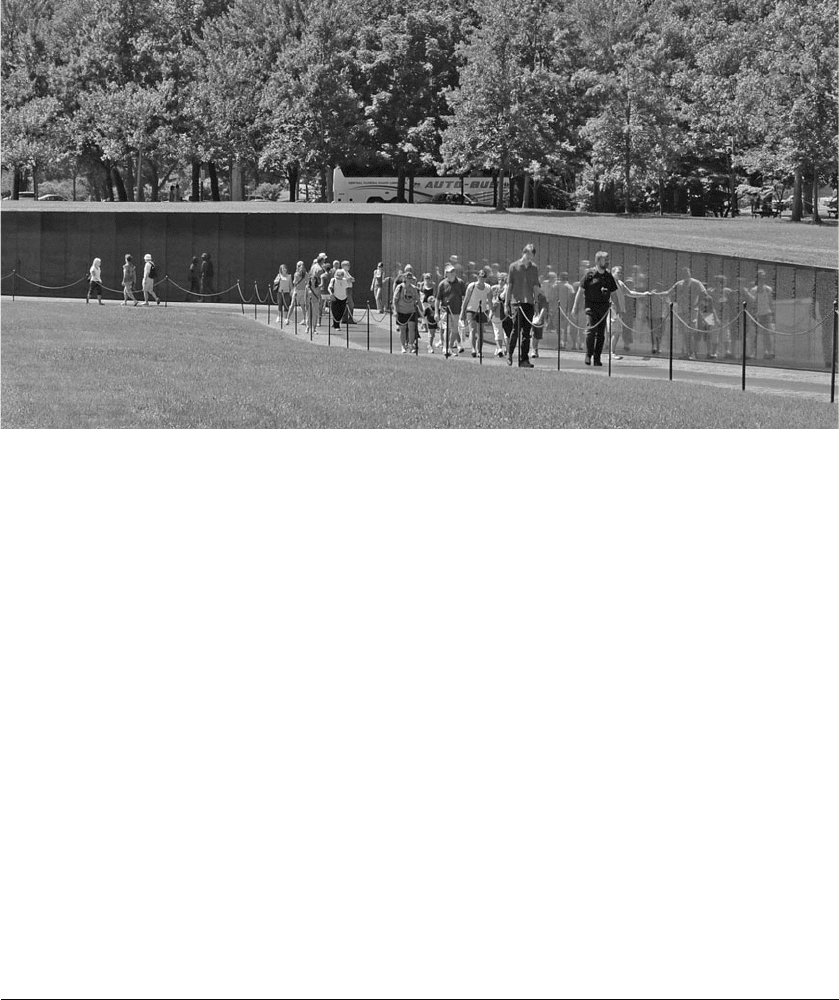

FIGURE 27.5 In Maya Lin’s Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C., the experience of touching the engraved names and simultaneously

moving down into and then up out of the earth evokes a haunting sense of another event, time, and place that is grounded in the haptic body.

(Photograph © 2009 Scott Nunemaker.)

Long description: This photo shows a group of visitors walking along the ascending path of the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, D.C. Am image

of the group is reflected in the polished black marble wall, and some people are touching the engraved names of soldiers as they move along.

27.8 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

(Pallasmaa, 2005), it is also that case that various forms of new architectural production can lead to

integrated and multisensory modes of engagement.

Inclusive design is primary among the approaches most conducive to investigate sensory experi-

ence in architecture. Critics have accused inclusive design practitioners of neutralizing the built

environment, of erasing difference. Inclusive design, if practiced conscientiously, actually does the

opposite; it focuses on difference and empowerment through multisensory approaches to design.

The challenge to designers is to (1) open sensory choices, (2) avoid the dangers of sensory overload,

and (3) practice multisensory design with precision and balance. Only then can it fulfill the overall

goal of life enrichment.

The home is the place to start this challenge. The incorporation of sensory design strate-

gies to domestic language not only enhances the personalization of these places but also allows

occupants of varying abilities to more fully access, be informed by, and enjoy the spaces of their

daily lives.

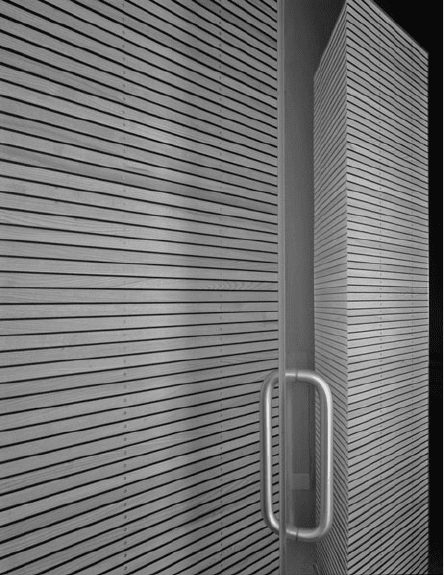

FIGURE 27.6 The bathroom wall surface in the La Marche Residence

in Derby, New York, is made of protruding thin rubber strips separated by

strips of ash, resulting in a wall that can be used to squeegee off water after

a shower and massage the back. (Photograph © 2006 William Helm.)

Long description: This photo shows one bathroom wall and a slightly

ajar, translucent glass entrance door with a stainless U. The wall surface is

constructed of black rubber strips that protrude ¼ in. separated by 1½-in.

strips of ash.

THE SENSORY HOUSE 27.9

27.9 BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Academy of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Smell and Taste; http://www.entnet.org/

HealthInformation/smellTaste.cfm. Accessed Mar. 10, 2009.

Anissimov, M., “How Does the Sense of Hearing Work?” WiseGeek; http://www.wisegeek.com/how-does-the-

sense-of-hearing-work.htm. Accessed Mar. 17, 2009.

Blesser, B., and L. Salter, Spaces Speak, Are You Listening? Experiencing Aural Architecture, Cambridge, Mass.:

MIT Press, 2007.

Cutnell, J. D., and K. W. Johnson, Physics, 4th ed., New York: Wiley, 1998.

Gatland, S., “Designing Environments for Sound Control,” The American Institute of Architects; http://www.aia.

org/practicing/groups/kc/AIAB058394. Accessed Mar. 20, 2009.

Gibson, J. J., The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1966.

Grimaldi, S., T. Partonen, S. I. Saarni, A. Aromaa, and J. Lönnqvist,

“

Indoor Illumination and Seasonal Changes

in Mood and Behavior Are Associated with the Health-Related Quality of Life,” Health and Quality of Life

Outcomes, Aug. 1, 2008; http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=2527305. Accessed Mar.

17, 2009.

Gutierrez, M. A. A., F. Vexo, and D. Thalmann, Stepping into Virtual Reality, London: Springer, 2008; http://

www.springerlink.com/content/u724585622343601/. Accessed Mar. 13, 2009.

Hall, E. T., The Hidden Dimension, Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books, 1969.

Harnett, E., “The Whole Package: The Relationship between Taste and Smell,” Serendip; http://serendip.bryn-

mawr.edu/exchange/node/1575. Accessed Mar. 14, 2009.

Molnar, J. M., and F. Vodvarka, Sensory Design, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004.

Pallasmaa, J., The Eyes of the Skin, Architecture and the Senses, Chichester, England: Wiley, 2005.

Reed, E. S., Encountering the World: Toward an Ecological Psychology, New York: Oxford University Press,

1996.

Schafer, R. M., The Tuning of the World, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1977.

Tanizaki, J., Praise of Shadows, translated by T. J. Harper and E. G. Seidensticker, London: Cape, 1991.

Tuan, Y. F., Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

1977.