Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

24.12 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

proximity to work, school, shopping, all with a greater reliance on public transportation. To be

sustainable, a community must support the integration, participation, and enhancement of the inde-

pendence of all people throughout the course of their daily lives (see Fig. 24.6).

24.6 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boyce, P., and J. Van Derlofske, Pedestrian Crosswalk Safety: Evaluating In-Pavement, Flashing Warning

Lights: Final Report, New York: Region II University Transportation Research Center, City College of

New York, 2002.

Gilderbloom, J. I., and J. Markham, “Housing Quality among the Elderly,” International Journal of Aging and

Human Development, 46(1), 1998.

Harmon, J. W., “Urban Design, Spaces and Human Scale,” Design Community Architecture Discussion; www.

DesignCommunity.com. Accessed Apr. 23, 2002.

Kaye, H. S., T. Kang, and M. LaPlante, “Mobility Device Use in the United States,” Institute for Health and

Aging, University of California, San Francisco, 2000, p. 32.

Mace, R. L., The Accessible Housing Design File, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1991.

Maryland Department of the Environment, Comprehensive Greenhouse Gas and Carbon Footprint Reduction

Strategy, 2008, pp. 75–105; www.mde.state.md.us.

FIGURE 24.6 A universally usable elevated sand table facilitates the park’s use by all

children and adults, promoting social integration and psychological inclusion. (Kids Together

Playground, Raleigh, N.C., Leslie Young, photographer.)

Long description: Photograph of a man seated in a power wheelchair pulled up under a canti-

levered sand table in a public park. With him are two young boys. The sand table is created by

a series of retaining walls, and at its highest point, the wheelchair user can pull into kneespace

to play with the two children, everyone at the same eye level. The sand table slopes to grade,

allowing children of all ages to walk or crawl and play in the sand. The lower retaining wall

provides seating for a parent or other supervisor.

UNIVERSAL HOUSING: A CRITICAL COMPONENT OF A SUSTAINABLE COMMUNITY 24.13

National Council on Disability, “Livable Communities for Adults with Disabilities,” Washington, 2004.

Smith, E., and S. S. Terry, “What Difference Has the ADA Made?” American Planning Association Magazine,

April 2002, p. 14.

U.S. Census Bureau, American Fact Finder, American Community Survey, 2005–2007; www.factfinder.census.

gov/servlet.

www.louisville.edu/org/sun/housing/cd_v2/Bookarticles/Ch1.htm. Accessed Aug. 6, 2001.

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER 25

THE EVOLUTION OF UNIVERSAL

DESIGN IN HOUSING IN THE

UNITED STATES: TOWARD

VISITABILITY AND PATTERN

BOOKS

Jordana L. Maisel

25.1 INTRODUCTION

The disability rights movement in the United States has been successful in achieving legislation that

guarantees people with disabilities the right of free and equal access to the physical environment.

Despite these successes, a critical accessibility problem still exists; physical barriers in almost all

single-family housing prevent many people with disabilities from enjoying the benefits of a home

of their own or require them to pay a premium to modify homes to their needs. The lack of acces-

sibility also creates barriers for older people seeking to age in place in their own home. This chapter

examines the current housing situation with respect to our aging population and an overview of

housing policy and legislation targeted toward seniors and people with disabilities. It also explores

more-recent innovative approaches to housing, including visitability and universal design, as well as

tools to assist in their implementation.

25.2 THE CURRENT HOUSING PROBLEM

The current housing stock fails to meet the needs and preferences of older adults and people with

disabilities, forcing many to unwillingly leave their homes and prematurely move to institutional

settings or to live with their families. Researchers and policy makers expect the need for accessible

housing to increase in the next few decades as the country’s population ages. The U.S. Census

Bureau estimates that the number of persons age 65 and older will grow to almost 40 million by the

year 2010 and 70 million by 2030 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2004). Compounding this is the fact that

approximately 70 percent of Americans live in single-family homes (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001), and

the overwhelming majority of these housing units have barriers that make it difficult or impossible

for someone with physical disabilities to enter and exit.

These barriers often have significant consequences. In addition to social isolation, many people

with severe mobility impairments may be unable to exit their homes independently in an emergency,

25.1

25.2 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

and these individuals risk injury from falling while being carried in and out of the home. Barriers

within a home can also increase the work and stress of the caretakers who assist older adults and

people with disabilities. Many family caregivers report that they suffer physical injuries as a result of

lifting and handling their relatives, as well as psychological health problems such as fatigue, anxiety,

and depression (Brown and Mulley, 1997).

Although a majority of older Americans prefer to stay in their homes, barriers can make it diffi-

cult for older adults to remain in their homes as they age. According to a 2004 survey conducted for

the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP), more than four in five (84 percent) persons

age 50 and older strongly or somewhat agree that they would like to remain in their current residence

for as long as possible (AARP/Roper Public Affairs and Media Group, 2005). Aging in place offers

numerous social and financial benefits. Research shows that independent living promotes life satis-

faction, health, and self-esteem, three keys to successful aging. Furthermore, older adults get a sense

of familiarity, comfort, and meaning from their own home (Herzog and House, 1991).

25.3 OVERVIEW OF HOUSING POLICIES AND PRACTICES

∗

As a response to this need for more accessible homes, changes in public policy and new design prac-

tices have emerged in the United States. While tremendous strides in accessibility legislation have

taken place over the past few decades, there is still much room for improvement.

While antisegregation laws have been advanced in education, employment, and health care,

housing has seen few gains in both the federal courts and everyday practice (Lamb, 2005). The Fair

Housing Amendments Act of 1988 expanded the scope of housing covered by accessibility laws to

all new multifamily housing, both public and private. The act required every unit in all newly con-

structed, multifamily, elevator-equipped housing with four or more units and all ground-floor units

of multifamily residences to be accessible.

Fair Housing, however, is merely one piece of legislation in the more than four decades-old

legislative history of disability rights in housing, which includes the Civil Rights Act (1964), Fair

Housing Act (1968), the Rehabilitation Act (1973), the Americans with Disabilities Act (1990),

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA, 1997 and 2004), and many others. Some legis-

lation, e.g., Fair Housing, centers on housing, while other legislation, e.g., IDEA, invokes housing

more indirectly, as location and quality of housing affect access to and effectiveness of education.

Three significant themes should be noted from an analysis of the most significant pieces of legis-

lation that influence housing for people with disabilities. First, the bulk of federal housing legislation

and programs focus on economic issues (i.e., income) and to a much lesser degree on disability-only

programs. Second, there is a trend away from the construction of federally owned/managed housing

(i.e., public housing). Presumably, this results from the negative criticisms (e.g., ghettoizing) that

public housing projects, such as Chicago’s infamous Cabrini-Green, have faced. Finally, the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) maintains the greatest number of housing-

related programs, but only a very small percentage focus on age- and disability-related housing.

Housing legislation, policy, and programs have transformed considerably since the inception

of Fair Housing in 1968. An overarching transformation can be conceptualized in terms of the

transformation from federal to local oversight which began in the early 1970s (Shlay, 2006). While

legislation, policy, and programs at the federal level have primarily focused on antidiscrimination

and the distribution of federal funds, the state and local municipalities have concentrated more on

accessibility policies. A second trend toward privatization of housing programs and funds further

reinforces the localized and individualistic concepts that make single-family housing so prevalent in

the United States, and underscores both the need for and growing interest in visitability.

*This text is adapted from Chap. 8, “Redefining Policy and Practice” (Brent Williams, Korydon Smith, and Jennifer Webb),

in the forthcoming book Just Below the Line: Disability, Housing, Equity in the South (Korydon Smith, Jennifer Webb, and Brent

Williams, eds.), to be published by the University of Arkansas Press.

THE EVOLUTION OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN IN HOUSING IN THE UNITED STATES 25.3

25.4 VISITABILITY AS AN ALTERNATIVE HOUSING POLICY

∗

Visitability represents a highly focused strategy in the continuing evolution of accessible housing

policy and practice in the United States. Visitability is an affordable, sustainable, and inclusive

design approach for integrating basic accessibility features as a routine construction practice into

all newly built homes. Visitability provides a foundation for improving the home with additional

universal design features, thereby lowering the cost of achieving higher levels of usability. Started in

the United States by Eleanor Smith and her group Concrete Change in 1987, visitability proponents

seek to make homes more accessible by having them meet only three conditions: (1) one zero-step

entrance at the front, side, or rear of the home; (2) 32-in.-wide clearances at doorways and hallways

with at least 36 in. of clear width; and (3) at least a half bath on the main floor (see Fig. 25.1).

Visitability provides benefits to a wide range of users, including those with disabilities, their

nuclear family, friends, and other relatives who may, from time to time, need to use wheelchairs or

other assistive equipment. Consequently, as a result of visitability, individuals with a variety of abili-

ties can interact with one another and participate in community activities outside of their homes.

As of January 2008, some 57 state and local initiatives had been adopted in the United States,

of which 33 (58 percent) are mandatory and the other 24 are voluntary. Local government officials

report that about 30,000 visitable homes have been built as a result of these efforts. Current visitability

initiatives vary significantly. For example, some visitability programs cover housing within an entire

state, whereas others affect only cities or counties. Another difference is that some programs strictly

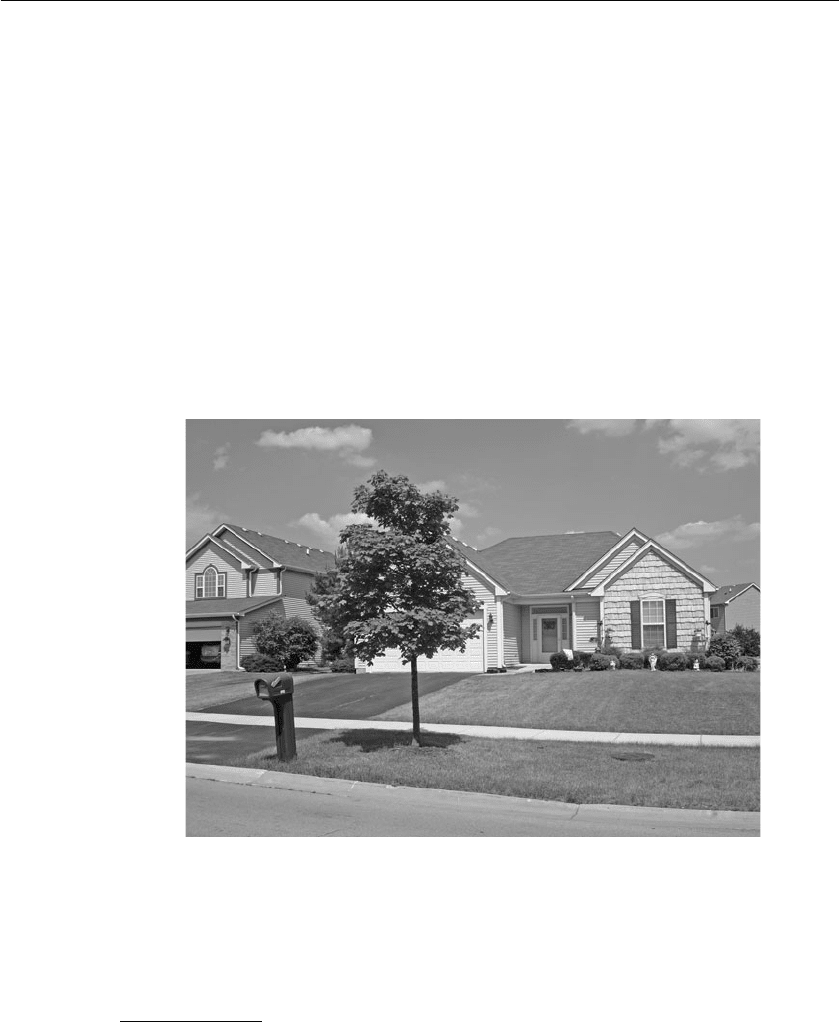

FIGURE 25.1 In 2003, Mayor Roger Claar signed a mandatory visitability ordinance in

Bolingbrook, Illinois. Since then, the more than 3500 new homes demonstrate that zero-step

entrances are practical even in cold-weather climates, are cost-effective even with basements,

and can be aesthetically pleasing, as evidenced by the home shown above. (Photograph courtesy

of Edward Steinfeld, IDeA Center.)

Long description: This photo shows a single-family home on a traditional, suburban residential

street in Bolingbrook, Illinois. The home has an asphalt driveway that leads to a concrete path-

way to the home’s front door. The pathway is slightly sloped and leads to a zero-step entrance.

*This text is adapted from “Increasing Home Access: Designing for Visitability” (Jordana L. Maisel, Eleanor Smith, and

Edward Steinfeld), published by the AARP Public Policy Institute, August 2008.

25.4 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

adhere to the three basic accessible features, whereas others include a few additional architectural

elements such as lever handles, blocking for grab bars in bathroom walls, and accessible environ-

mental controls. Visitability programs also vary in how they are implemented. Some are mandatory,

with a law or an ordinance requiring builders to include the visitable features during new construc-

tion. Others are voluntary. With regard to scope, some ordinances cover only houses constructed with

some form of government assistance, whereas a few ordinances cover every new house built (i.e.,

Pima County, Arizona; Bolingbrook, Illinois; and Tucson, Arizona).

Several foreign countries have national policies that require all new housing to include accessibility

features. In the United Kingdom, Part M of the national building code requires basic access features

for any new dwelling unit, whether it is a single-family or multifamily unit. Sweden, Denmark, and the

Netherlands also require basic access features in all dwelling units. Other highly developed countries such

as Canada and Australia have movements to expand accessible housing policies to universal coverage of

single-family homes. A new effort underway in the United States could lead to enactment of a national

policy. The ICC/ANSI A117.1 Standard for accessible design is the national consensus standard refer-

enced by most building codes in the country. The committee that promulgates the standard recently devel-

oped a new section, Type C Dwelling Units, with technical design criteria for visitability. Developing

consensus-based technical standards for visitability features will reduce confusion about exactly how to

design a zero-step entry, an accessible bathroom, and accessible doorways. The Type C technical informa-

tion will be in the 2009 ICC/A117.1 Standard for jurisdictions to reference in their ordinances if they so

desire, thus promoting uniformity in applications and aiding in their interpretation.

25.5 UNIVERSAL DESIGN IN HOUSING AND THE ROLE OF

PATTERN BOOKS

∗

Moving beyond visitability, universal design provides an even wider array of features that improve usability,

safety, and health for a more diverse group of people and abilities. In many countries, new housing designed

for older people is being produced with a high accessibility standard to reduce the need for relocation and

supportive services over time. This type of housing, sometimes called aging-in-place or life span housing,

has many universal design features and represents a noteworthy development in the field of housing.

Design for aging in place should include a broader range of features than accessible and visit-

able housing. In particular, design for sensory limitations, security, and the prevention of falls is a

key goal. Moreover, community context is also important. Aging in place, with any decent level of

quality of life, requires livable neighborhoods that have conveniently located community services,

opportunities for recreation and work nearby, a vibrant street life, and informal gathering places

through which neighbors can more easily get to know one another.

Although the features of other types of accessible housing have been codified by various laws

and the ICC/ANSI A117.1 Standard, there has not been a codification of life span design housing in

the United States. A U.K. standard, Lifetime Homes, does identify 16 specific design features that

together create more accessible and adaptable housing.

The Lifetime Home Standard (LTH) criteria (Habinteg Housing Association. n.d.) include

1. Car parking width

2. Access from car parking

3. Approach gradients

4. Entrances

5. Communal stairs and lifts

6. Doorways and hallways

*This text is adapted from Inclusive Housing: A Pattern Book (Edward Steinfeld and Jonathan White), published by W.W.

Norton & Company.

THE EVOLUTION OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN IN HOUSING IN THE UNITED STATES 25.5

7. Wheelchair accessibility

8. Living room

9. Entrance level bedspace

10. Entrance level WC and shower drainage

11. Bathroom and WC walls

12. Stair lift/through-floor lift

13. Tracking hoist route

14. Bathroom layout

15. Window specification

16. Controls, fixtures, and fittings

In Inclusive Housing: A Pattern Book, the authors go beyond the criteria outlined in the LTH to

include more features related to the senses and cognition. Their interpretation of the concept includes

both “essential” and “optional” features.

Essential life span housing design features:

• One no-step path to a no-step entry that can be at the front, side, or rear or through a garage

• No-step access to patios, balconies, and terraces

• Doorways that have at least a 32-in.- (815-mm-) wide, clear opening

• Hallways and passageways that have 42-in. (1065-mm) clearance minimum

• Basic access to at least one full bath on the main floor

• Reinforced walls at toilets and tubs for future installation of grab bars

• Cabinetry in kitchen that allows a resident to work in a seated position

• Light switches and electrical outlets between 15 and 48 in. (380 and 1220 mm) from finished floor

• Stairways with tread widths at least 11 in. (280 mm) deep and risers no greater than 7 in. (180 mm) high

• Good lighting throughout the house including task lighting in critical locations (e.g., under kitchen

cabinets)

• Nonglare surfaces

• Contrasting colors to promote good perception of edges and boundaries

• Clear floor space of at least 30 in. × 48 in. (760 mm × 1220 mm) in front of all appliances and

fixtures and cabinetry

• Front-loading laundry equipment

• Ample kitchen storage within 24 to 48 in. (610 to 1220 mm)

• Comfortable reach zone

Optional life span housing design features (partial list):

• No steps on paths and at all entries

• One-story plan, or residential elevator, or stacked closets and framed out ceiling/floor to allow

future installation of a residential elevator

• Adjustable-height kitchen sink

• Cabinets with built-in convenience features, e.g., full-extension sliding drawers and shelves

• Smart house system

One of the most promising areas for application of universal design is the introduction of

information technology in the home. Most appliance companies and other product manufactur-

ers are engaged in research to develop “smart products.” Technologies already available or under

25.6 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

development include devices that provide more powerful remote control functions, home monitor-

ing systems that can notify service providers of the need for assistance, and smart tags that will

help to maintain an inventory of food and other supplies. It is essential that the new generation of

products be universally designed to accommodate disability and be made truly usable for the older

population (see Norman, 2007).

Pattern books serve as a valuable tool to help professionals practice good design. They

provide detailed drawings and descriptions that assist designers and home builders through the

design and construction process. For example, Inclusive Housing: A Pattern Book presents com-

mon prototype block, lot, and house plans and evaluates the accessibility of each. It describes

the components that support inclusive design within a home and provides examples to illustrate

applications of these strategies. While recommendations are provided for other features, this

book focuses on the most critical issues of space planning for wheeled mobility. Designing access

for wheeled mobility affords generous space clearances for all users, makes a house feel more

spacious and comfortable, and provides a foundation for future upgrades toward life span design

(see Figs. 25.2 and 25.3).

25.6 MOVING FORWARD

Housing policies, once effective, no longer match the current demographic makeup or cultural pre-

dilections of today’s society (Williams et al., forthcoming). As the demographic shift compounds

the current lack of accessible housing and neighborhoods, a growing segment of the population will

confront challenges in the usability of their dwellings.

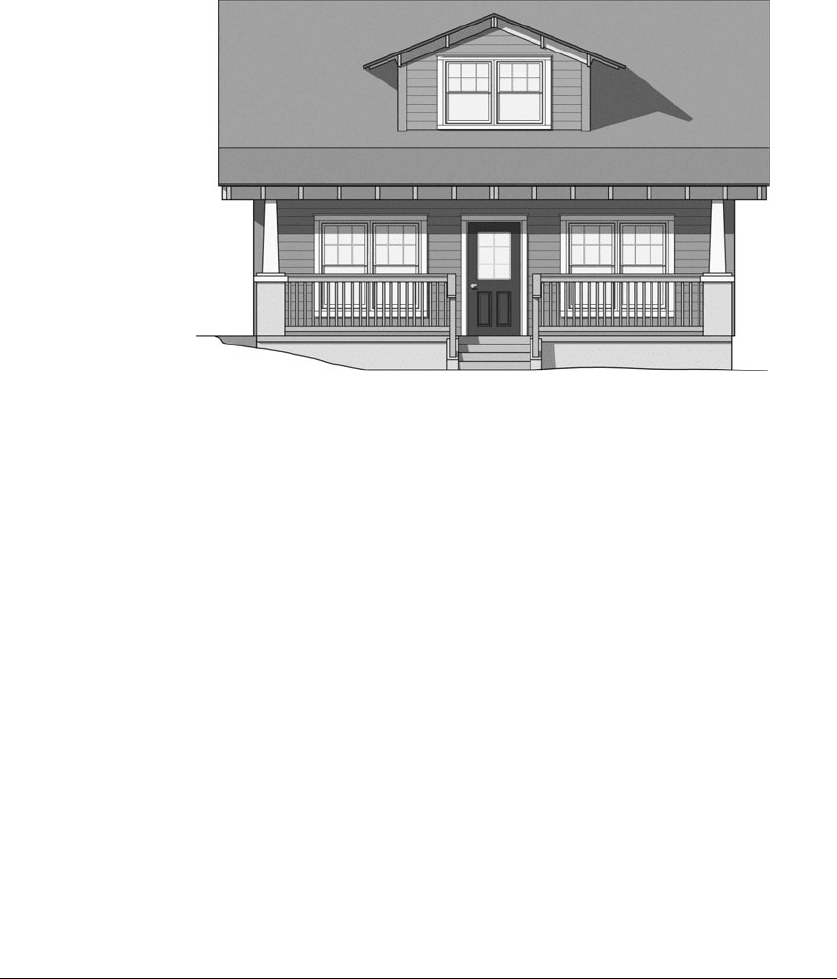

FIGURE 25.2 This three-bedroom, two-bathroom American Craftsman Bungalow single-

family house, while initially inaccessible due to the front porch, was redesigned to include

a cross-sloping lot with an on-grade front entry. The space-efficient plan contains generous

circulation clearances, an L-shaped kitchen, one visitable full bathroom, and two accessible

bedrooms. (Image courtesy of Steinfeld and White, 2010.)

Long description: This image shows a single-family, two-story home designed in the American

Craftsman Bungalow style. The home has four steps leading to a front porch. There is a central

wooden door flanked by two windows on either side. From the front elevation of the image there

does not appear to be an accessible entrance; however, an accessible, no-step entrance is created

from the cross-sloping of the lot (which is not seen in the image).

THE EVOLUTION OF UNIVERSAL DESIGN IN HOUSING IN THE UNITED STATES 25.7

Whether through visitability, universal design, or other innovative approaches, producing an

environment that is more inclusive will reduce the need for specific accommodations for people with

disabilities. Moreover, the benefits for all will generate a larger constituency to support the provision

of increased usability.

Incorporating more innovative and cost-effective design practices into the new housing stock,

with assistance from model standards, commitment programs such as Lifetime Homes, and pat-

tern books, will help create a larger supply of homes that support seniors’ housing preferences.

Facilitating seniors’ ability to age in place, rather than in expensive assisted living and nursing

homes, will help save taxpayer money as well as foster seniors’ autonomy and dignity. To accom-

plish this incredible feat, designers, builders, planners, and policy makers must become more aggres-

sive in their efforts. They need to utilize more-proactive strategies to ensure tomorrow’s housing

supply meets the needs of today.

25.7 BIBLIOGRAPHY

AARP/Roper Public Affairs and Media Group of NOP World, Beyond 50.05, A Report to the Nation on Livable

Communities: Creating Environments for Successful Aging, Washington: American Association of Retired

Persons, May 2005.

Allen, C., “Disablism in Housing and Comparative Community Care Discourse—Towards an Interventionist

Model of Disability and Interventionist Welfare Regime Theory,” Housing, Theory and Society, 16(1): 3–16,

1999.

Brown, A. R., and G. P. Mulley, “Injuries Sustained by Caregivers of Disabled Elderly People,” Age and Ageing,

26:21–23, 1997.

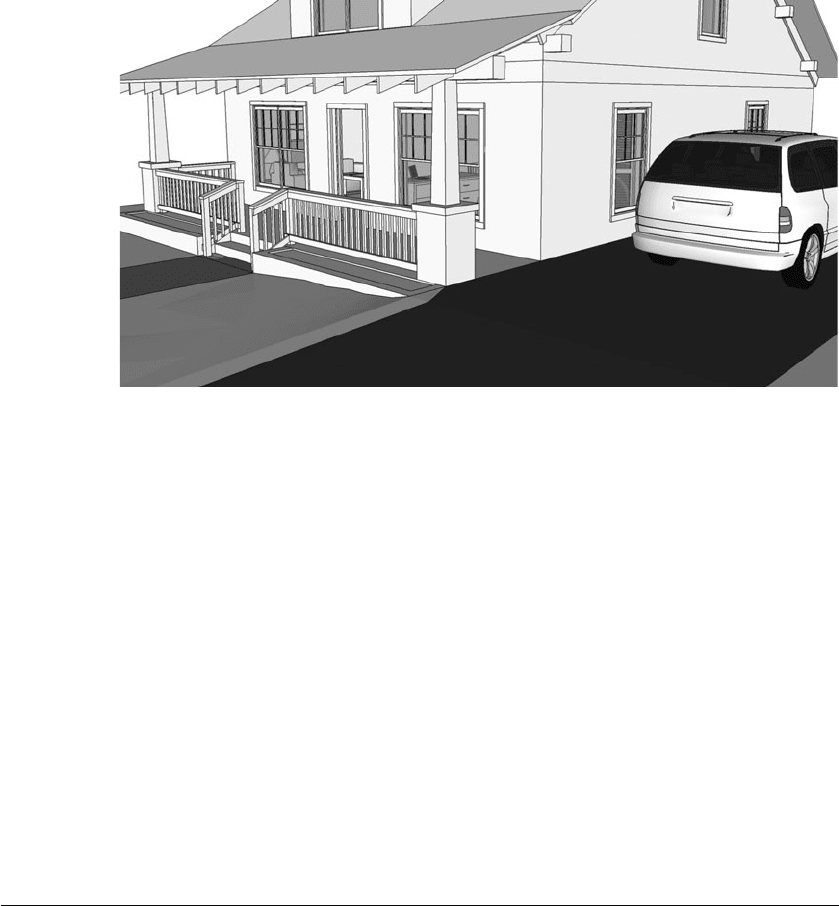

FIGURE 25.3 This image shows the stepless entrance that is created by cross-sloping a lot. The driveway is slightly

sloped to create a stepless transition from the driveway to the front porch to the front door. (Image courtesy of Steinfeld

and White, 2010.)

Long description: This black-and-white image shows a drawing of a single-family, two-story house, with a minivan

in the driveway. The image is taken from the perspective of a person looking at the front porch and front entrance from

the driveway. There is a porch that extends along the entire length of the house and has a wooden banister. The image

clearly shows how the front porch opens up to the asphalt driveway along the right side without any changes in elevation.

Therefore, a stepless entrance is created from the driveway to the front entrance.