Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

22.6 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

If water play is provided, a part of the surface area must be wheelchair accessible. If the water

source is manipulated by children, it must be usable by all children. If loose parts such as buckets

are provided and children have access to the equipment storage, the storage must be usable by all

children. When water is provided for play, the following dimensions apply:

• Forward reach: 36 to 20 in.

• Side reach: 36 to 20 in.

• Clear space: 36 × 55 in. The clear space should be located at the part of the water-play area where

the most water play will occur. If the water source is part of the active play area and children turn

the water on and off, it must be accessible. If the water source is part of a spray pool, the area

under the spray should be accessible. Accessibility should involve the dimensions for both clear

space and reach.

• Clearance ranges: top height to access water, 30 in. maximum; under clearance, 27 in. minimum.

Sand-Play Areas

Children will play in dirt wherever they find it. Using props such as a few twigs, a small plastic toy,

or a few stones, children can create an imaginary world in the dirt, around the roots of a tree, or in

a raised planter. The sandbox is a refined and sanitized version of dirt play. It works best if it retains

dirt play qualities. The sand area should be large with small, intimate spaces designed into it, with

access to water and small play props (see Fig. 22.4).

FIGURE 22.3 Water sprays installed below a rubber surface provide water play for everyone.

Long description: This photo shows the water-play area at the Jacksonville Children’s Zoo in Jacksonville, Florida.

In the photo children play in water sprays placed at ground level as well as within large whale sculptures and other sea

creatures found in the ocean near Jacksonville. Rubber safety surfacing covers the ground plane, and planting surrounds

the water-play area.

OUTDOOR PLAY SETTINGS: AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH 22.7

If a sand-play area is provided, part of it must be accessible. Important elements are clear floor

space, maneuvering room, reach and clearance ranges, and operating mechanisms for control of sand

flow. When products such as buckets and shovels will likely be used in the sand-play area, storage

places should be at accessible reach range.

Raised sand play is a very limiting play experience because of the way a raised area must be

constructed. To provide a place for the wheelchair user under the sand shelf, there is very little depth

of sand available for play. Therefore, a raised sand area by itself is not a substitute for full-body

sand play.

If the sand area is designed to allow children to play inside the area, a place should be provided

where a participant can rest or lean against a firm, stationary back support in close proximity to the

main activity area. Back support can be provided by any vertical surface that has a minimum height

of 12 in. and a minimum width of 6 in., depending on the size of the child. Back support can be a

boulder, a log, or a post that is holding up a shade structure. A transfer system into a sand area may

also be necessary if the area is large and contains a variety of sand activities. A transfer system is

appropriate if there are no areas of raised sand play in the primary activity area, or if the sand area is

over 100 ft

2

and the raised sand area would tend to isolate accessible sand-play activities.

FIGURE 22.4 Giant nautilus water-play element.

Long description: This photo shows a child touching a nautilus-

shaped play element with water running through it at Chase

Palm Park in Santa Barbara, California. The nautilus is part

of the sand- and water-play area in the park and is made from

concrete with inlaid stones and pebbles.

22.8 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

When raised sand is provided, the following clearance ranges apply:

• Top height to sand: 30 to 34 in. maximum

• Under clearance: 27 in. minimum

• Side reach: 36 to 20 in.

• Forward reach: 36 to 20 in.

• Clear space for wheelchair: 36 × 55 in.

Depending on the site conditions and the amount of sand play, shade may be required. It may be

provided through a variety of means, such as trees, tents, umbrellas, structures, and so forth. This

advisory requirement for shade is based on the site context, program, and users. Some shade in or

around sand is usually desirable, but sand needs sunlight to dry out and keep clean.

Gathering Places

To support social development and cooperation, children need comfortable gathering places. Parents

and play leaders need comfortable places for washing up, sitting, socializing, and supervising (see

Fig. 22.5). If gathering places are provided, a portion of them should be accessible and serve people

of all ages. A gathering place contains fixed elements to support playing, eating, watching, talking,

or assembling for a programmed activity:

• Seating. At least 50 percent of fixed benches should have no backs and arms so they can be used

for a variety of activities, not just sitting.

• Tables. Provide a variety of sizes and seating arrangements.

• Game tables. Game tables provide a place for two to four people to play board games. If fewer

than five game tables are provided, a minimum of one four-sided game table should include an

accessible space on one side.

FIGURE 22.5 Accessible washup sink serves people of all ages and abilities.

Long description: This photo shows an adult sitting in a wheelchair washing his hands at an

accessible sink in Flood Park, located in Menlo Park, California. The sink is made of concrete

and can be used sitting down or standing up.

OUTDOOR PLAY SETTINGS: AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH 22.9

• Storage. If storage is supplied and a part of the gathering area and the storage are used by children,

accessible shelves and hooks should be a maximum of 36 in. above the ground. The amount of

storage is dependent upon program requirements.

• Shade. Shade may be desirable for gathering areas where people will be participating in activities

over a long time. Shade can be provided by a variety of means such as trees, canopies, or trellises,

depending on site context.

Garden Settings

Gardening, a powerful play-and-learn activity, allows children to interact with nature and one another.

Gardens in play areas primarily provide activities of planting, tending, studying, and harvesting

vegetation. Depending on the type and height of plantings, planter boxes may require a raised area

for access or transfer. A garden must provide a minimum of one accessible garden plot.

If a raised garden area is provided, it should have the following features:

• The raised area should be located as part of the main garden area. The amount of raised area is

determined by the program, but a minimum of 10 percent of the garden should be raised.

• The edge should be raised above the ground surface to a minimum of 20 in. and a maximum of

30 in.

The garden growing area should allow access either by side or by forward reach 12 to 36 in. above

the ground.

• Transfer systems. If children are required to sit in the dirt to garden, a transfer point should be

provided that enables a participant to transfer into the garden.

• Potting and maintenance areas. Potting and preparation areas should allow access by either for-

ward or side reach. The amount of area to be made accessible depends on the program. At least

one workstation for potting should be made accessible.

• Storage. Storage areas for the garden should provide access for children who use wheelchairs.

Hooks and shelves should be a maximum of 36 in. off the ground.

• Circulation. Aisles around the garden (36 to 44 in.) should be provided on a main aisle so a child

using a wheelchair or walker can get to the garden. This larger aisle (48 to 60 in.) should also

provide access to the accessible gardening spaces.

Landforms, Vegetation, and Trees

Landforms, vegetation, and trees should be integrated into the flow of play activities and spaces, and

they can be play features in themselves.

Landforms help children explore movement through space and provide for varied circulation.

Topographic variety stimulates fantasy play, orientation skills, hide-and-seek games, viewing, roll-

ing, climbing, sliding, and jumping. “Summit” points must accommodate wheelchairs and provide

support for children with other disabling conditions.

Trees and vegetation comprise one of the most ignored topics in the design of play environments.

They are two of the most important elements for social integration because everyone can enjoy and

share them. Vegetation stimulates exploratory behavior, fantasy, and imagination. It is a major source

of play props, including leaves, flowers, fruits, nuts, seeds, and sticks. It allows children to learn

about the environment through direct experience.

Designers and program providers should emphasize integrating plants into play settings rather

than creating separate “nature areas.” For children with physical disabilities, the experience of being

in trees can be replicated by providing trees that a wheelchair user can roll under. An accessible

mini-forest can be created by planting small trees or large branching bushes.

22.10 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

If vegetation, trees, or landforms are used, access also needs to be provided. Tree grates and other

site furniture that support or protect the feature must be selected so as not to entrap wheels, canes,

crutch tips, etc.

Entrances and Signage

Entrances are transition zones that help orient and inform users and introduce them to the site. They

are places for congregating and for displaying information. Not all play areas, though, have defined

entrances. Sometimes entry to a play area can be provided from all directions.

Expressive and informative displays use walls, floors, ground surfaces, structures, ceilings, sky

wires, and roof lines on or near a play area to hang, suspend, and fly materials for art and education.

Signage is a visual, tactile, or auditory means of conveying information, and it must communicate a

message of “All Users Welcome.”

22.4 CONCLUSION

Play is learning. Play helps children to express, apply, and assimilate knowledge and experiences. A

rich play environment encourages all children to grow and develop into healthy adults. Most children

today have very sanitized, “packaged” play experiences. Many urban children have never built a fort

or “claimed” a piece of an outdoor environment as their own private adventure area.

One day the author was walking through a housing development that was under construction.

There were piles of dirt and boards around—great fort-building materials! On top of one dirt pile was

a 5-year-old boy, and at the bottom of the pile was his grandfather watching him play.

The construction foreman soon came over to the grandfather and told him that the boy must get

off the dirt because his liability insurance would not cover it. The grandfather told the boy what the

foreman said. The child looked around and just could not understand why he could not play there.

He knew he was doing nothing wrong. The grandfather tried to explain to the child. Finally the boy

got up off the pile of dirt, looked around, and said to the grandfather, “A kid’s gotta do what a kid’s

gotta do.” It is the responsibility of every adult and every institution that serves children to create

places so that a kid—any kid—can do what a kid’s gotta do.

22.5 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Goltsman, S. M., and D. S. Iacofano, The Inclusive City, Berkeley, Calif.: MIG Communications, 2007.

Moore, R. C., Plants for Play: A Plant Selection Guide for Children’s Outdoor Environments, Berkeley, Calif.:

MIG Communications, 1993.

———, and H. H. Wong, Natural Learning: Creating Environments for Rediscovering Nature’s Way of Teaching,

Berkeley, Calif.: MIG Communications, 1997.

———, D. S. Iacofano, and S. M. Goltsman, Play for All Guidelines: Planning, Design, and Management of

Outdoor Play Settings for All Children, Berkeley, Calif.: MIG Communications, 1992.

PLAE, Inc., Universal Access to Outdoor Recreation Areas: A Design Guide, Berkeley, Calif.: MIG

Communications, 1993.

U.S. Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board, Recommendations for Accessibility

Guidelines: Recreational Facilities and Outdoor Developed Areas, Washington: Access Board, 1994.

CHAPTER 23

OFFICE AND WORKPLACE

DESIGN

James L. Mueller

23.1 INTRODUCTION

The unemployment rate among Americans with disabilities remains well above that of nondisabled

Americans (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2009) despite passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act

(ADA) of 1990 and the American with Disabilities Act Amendments Act of 2008 (ADAAA), which

ensured the rights of individuals with disabilities in the workplace and in the community. The Ticket

to Work and Self-Sufficiency Act was passed in 1999 to remove financial disincentives to work for

people with disabilities. As the workforce ages and the cost of work disability rises, demographic and

economic trends have combined with legislation regarding employment of people with disabilities to

make universal design in the workplace a powerful issue. Workplace design that considers age-related

changes in vision, hearing, posture, and mobility will be critical to an aging workforce expected to

work even further into their senior years than previous generations (Taylor et al., 2009).

This chapter discusses how these trends impact designers and manufacturers of furniture, equip-

ment, materials, and other workplace products. This chapter also presents specific examples of how

designers, employers, and manufacturers have responded by implementing the concept of universal

design.

23.2 ECONOMIC BACKGROUND

“What do you do for a living?” is one of the first questions posed when people meet. Especially in

the United States, one’s personal identity depends heavily on what he or she does for a living. But

approximately two-thirds of Americans with disabilities are unemployed. This is an enormous bur-

den on them and on their families. Hundreds of thousands of employees become disabled each year

and leave the workplace permanently. Their former employers must bear the burden of replacing

them as well as paying disability benefits, and taxpayers must help fund public benefit programs for

them such as Social Security Disability Income (SSDI).

The SSDI program is the primary source of income for millions of Americans considered too dis-

abled to work. Between 1985 and 1994, SSDI payments doubled from $19 billion to $38 billion (U.S.

General Accounting Office, 1995). By 2003, this total had reached $70 billion (U.S. Government

Accountability Office, 2004). Realizing that continuing increases like these could destroy the nation-

al budget, Congress passed the Ticket to Work and Self-Sufficiency Act of 1999 to provide greater

vocational rehabilitation services and financial incentives to enable more Americans with disabilities

23.1

23.2 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

to work (Social Security Administration, 2000). Fostering work among SSDI recipients continues to

be an important priority in the government’s agenda regarding disability policy (Benitez-Silva et al.,

2006). Workplace design that considers the needs of workers with disabilities in both the public and

private sectors promises to continue to be important to the national economy.

The workplace is the site of millions of injuries per year. A permanently disabled employee can

cost his or her employer thousands of dollars in benefits, insurance costs, and lost productivity.

Thirty percent of current American workers will become disabled before retirement. Twenty percent

will experience an accident or illness that will keep them out of work for at least a year (National

Safety Council, 2008). But not all disabilities are caused at work.

Seventy percent of all people with disabilities are not born with them, but develop them during

the course of their lives (Louis Harris and Associates, 1994). As more people live longer lives, the

likelihood of experiencing a disability during one’s lifetime increases. Medical progress has had a

profound effect on treatment of illness and accidents that a short time ago might have been fatal

(Lew, 2005).

Historically, both government and business have been more willing to pay cash benefits than to

provide assistance to help disabled workers return to productive employment. Consequently, federal

work incentive programs for people with disabilities have struggled to gain traction (Ticket to Work

and Work Incentives Advisory Panel, 2007). Among private businesses, costs of insurance, employee

replacement, and workers’ compensation and other disability benefits have prompted long-term

disability insurers to institute comprehensive rehabilitation and return-to-work programs. These

programs have been shown to yield excellent returns on investment (Beal, 2007).

Both the ADA and ADAA, as well as their predecessor, the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, prohibit

employers from discriminating against individuals with disabilities who are qualified and able to per-

form the essential duties of an available job, with or without reasonable accommodation. Although

these laws have boosted the employment rights of people with disabilities, they have had little effect

on the level of unemployment among people with disabilities.

Occupational injuries and the steadily aging workforce ensure that disability will continue to be

a common concern among American workers and their employers. Compared with the enormous

cost of paying disabled employees not to work, making accommodations to bring them back to the

job is cheap. According to ongoing studies by the Job Accommodation Network (JAN), 56 percent

of accommodations cost absolutely nothing to make, while the rest typically cost only $600 (Job

Accommodation Network, 2009).

23.3 JOB ACCOMMODATIONS FOR EVERYONE EQUAL

UNIVERSAL DESIGN IN THE WORKPLACE

Job accommodations usually benefit coworkers without disabilities as well as the worker request-

ing accommodation. It is rare that on-site job accommodation needs analysis fails to reveal risks of

reinjury to the returning disabled worker that are also hazards to other employees. Accommodations

developed with this in mind bring employers the double benefit of accommodating as well as pre-

venting disability.

At the very least, job accommodations for workers with disabilities should be “transparent” or

have no effect at all on coworkers or customers. This is not as difficult as it may sound. For employers

with little experience with disabilities, it can be very difficult to imagine how an employee with

very different abilities from his or her coworkers might share similar needs. But the same barriers to

productive and safe work faced by an employee with a significant disability are usually barriers to

nondisabled coworkers as well, although perhaps to a lesser degree.

For example, an individual with limited manual strength and coordination was hired by a window

manufacturer to insert weather strip into 12-ft sections of window frame channel. Previous workers

had used a pair of pliers to tightly grasp the end of the weather strip in order to pull it the length of

the channel. Even for workers with a very strong grip, this was a tiring job that often caused consid-

erable hand pain by the end of a workday.

OFFICE AND WORKPLACE DESIGN 23.3

The newly hired individual with manual limitations was unable to exert adequate grip on the pli-

ers to pull the weather strip through the channel without slipping. To accommodate this limitation,

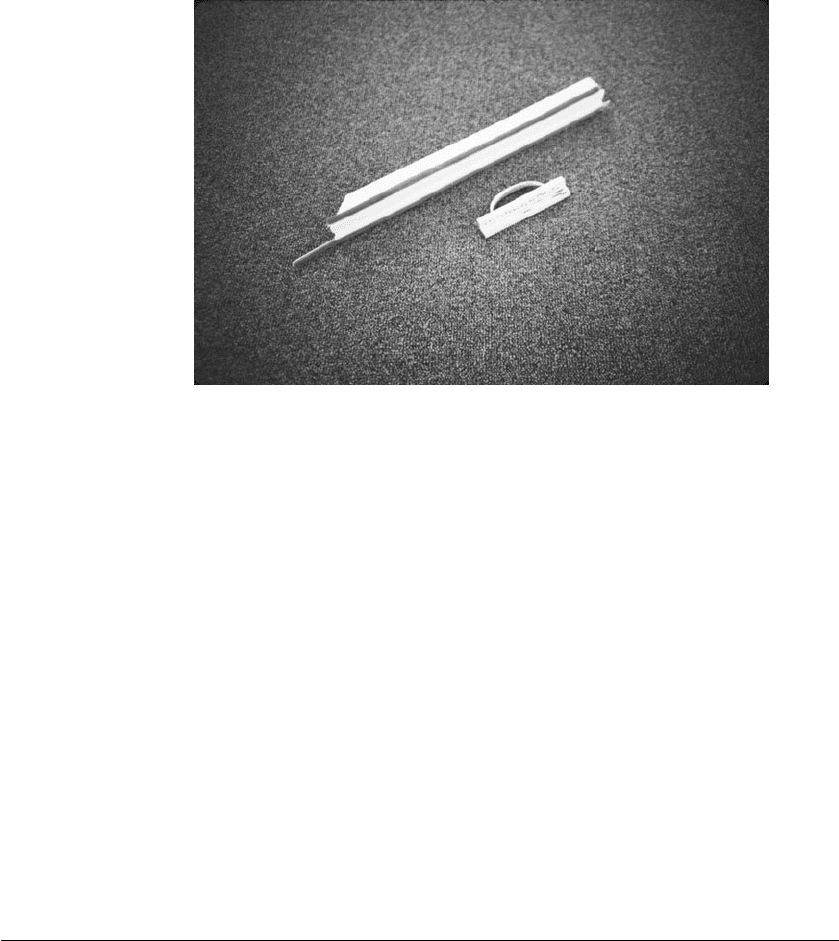

the author designed a simple tool, shown in Fig. 23.1, shaped to fit the channel, with a large hand

loop and a toothed gripping surface for the weather strip. The worker was then able to hold the tool

without gripping tightly and was able to use his body weight on the tool to supply adequate pressure

on the toothed gripping surface. The rest of the task simply required him to walk the length of the

channel. Both his coworkers and his supervisor were surprised at the ease with which he was now

able to perform a task that had been difficult for even the strongest employees. Not surprising, the

supervisor suggested that all workers use this tool.

There are many examples like this of successful job accommodation benefiting all workers.

Employers in these situations commonly ask, “Why didn’t we do this in the first place?” With

growing emphasis on reducing risk of cumulative and repetitive-stress injuries, the supervisor in the

aforementioned example might well have asked this very question. He realized the importance of the

simple tool in preventing injuries to other employees as well as in accommodating the worker with

the disability. In situations like these, employees formerly seen as “different” due to their disabilities

helped to identify job and workplace design problems affecting all workers. Their ergonomic needs

become effective templates for improvements in job and workplace design for all.

23.4 WORKING TOWARD A UNIVERSAL WORKPLACE

Working with the Computer/Electronic Accommodations Program (CAP) of the U.S. Department of

Defense, the author applied this principle to the development of a workbook for workers and supervisors to

assess the fit between the employee and his or her workplace. The intent of this effort was to identify

workplace design factors that might be barriers to workers with disabilities as well as risks to work-

ers not yet experiencing a disability. The result was CAP’s Workplace Ergonomics Reference Guide.

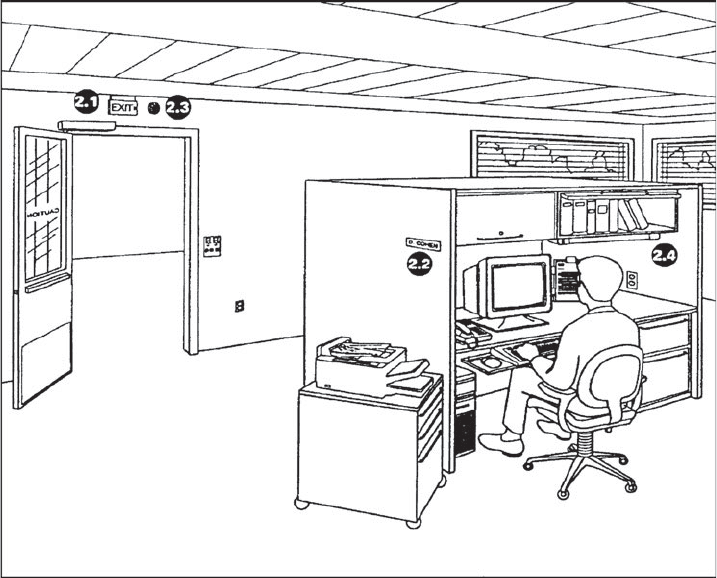

Two illustrations from this guide are shown in Figs. 23.2 and 23.3.

FIGURE 23.1 Simple tool for gripping weather strip.

Long description: This photo shows an 18-in. section of plastic window frame with weather

strip inserted. Below is a 6-in. tool with handle and protruding points for gripping weather

strip.

23.4 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

2. Is all visual and auditory information clear and easy to understand?

2.1 Can see and hear important information from anywhere in your work area? ___Yes ___No

2.2 Can see important information in very bright or very dim light? ___Yes ___No

2.3 Can you hear important information above the noise? ___Yes ___No

2.4 Is your work area quiet enough for conversations and telephone use? ___Yes ___No

Ergonomic Needs Assessment Visual and Auditory Information

FIGURE 23.2 Illustration from the Workplace Ergonomics Reference Guide.

Long description: This line drawing shows a woman seated in a wheelchair facing a computer monitor, telephone,

lamp, and document stand on a table. She is wearing a cordless headset. Her hands are positioned on a keyboard mounted

on a slide-out tray, which also holds a computer mouse. Beneath the table is the computer CPU. In the background is a

window with blinds and a view of trees beyond.

OFFICE AND WORKPLACE DESIGN 23.5

2. Is all visual and auditory information clear and easy to understand?

2.1 To make vital information seen and heard throughout the work area...

2.2 To make visual information understandable in very bright or very dim light...

2.3 To make auditory information heard above noise...

2.4 To make the work area quiet enough for conversations and telephone use...

For numbers, use arabic (1, 2, 3, 4) rather than Roman (I, II, III, IV) numerals

Reinforce text message with familiar symbols wherever possible

Avoid very high or very low tones

Reinforce auditory information with visual signals

Use sound-absorbing ceiling tile, wall coverings, and carpeting to minimize reflected sound

Add volume control or headset to telephone, use e-mail, or set aside “quiet area” for meetings

If work area is noisy, amplify loudness to exceed usual noise level

Locate visual information according to its importance-direct line of sight from workstation to

emergency signs, less important signs away from center of vision

Ensure adequate lighting on all visual information; lighting should strike signs at an angle of about

45 degrees

Wherever possible, communicate information through sight, sound, and touch (example: vibrating

pager with visual display)

Use matte, non-glare surfaces on signs; clearly contrast color, brightness, and texture of lettering

with background

Use sharp san-serif typestyle with clear distinction between similar shapes (0 and O, A and 4, 1

and I, I and I); for large bodies of text, use serif typestyle, such as Times Roman

Use caps and lower case, except for tactile signs, which should be all UPPER CASE, 5/8" - 2"

high, with extended letter, spacing and accompanied by Braille

Tactile lettering should be located 60" above floor; raised 1/32" where dirt may fill recessed

lettering, recessed where raised lettering might cause confusing shadows on raised lettering

Avoid underlining and borders around lettering, and avoid tight spacing between letters, words,

and lines

Minimize or isolate noise from air conditioning and other equipment with isolation mounts or

enclosures; locate copiers, printers, etc. in sound-proof area near work station

Install sound absorbing panels at work stations to minimize distractions or provide privacy: 29–41"

for modesty screens, 41–69" for seated privacy, 70–73" for standing visual and acoustical privacy

FIGURE 23.2 (Continued)