Preiser W., Smith K.H. Universal Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

30.8 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

These bathrooms reflect the social and inclusive philosophy of universal design. They have

the potential to unify diverse population groups, so no one user group is excluded by their design.

Existing bathrooms, with permanently installed fixtures, symbolize the idea that one bathroom

design fits all users. They tend to homogenize through uniformity. The two innovative bathrooms, on

the other hand, encourage individualization through flexibility and choice, so users can adapt their

bathrooms to suit their personal tastes and preferences.

30.5 THE FUTURE OF THE UNIVERSAL BATHROOM

The current approach to bathroom development has focused on designing task-oriented fixtures—

sink, toilet, and tub/shower—with little consideration for their use, placement, and how they make

up the bathroom environment. These fixtures require people to use them individually and move

around to perform bathroom activities. Emphasis on task-oriented fixture design, rather than on the

bathroom as a place to carry out daily hygiene, undermines the relationships between fixtures and

forces moving around to perform bathroom activities. For example, shower designs do not support

shaving and brushing when showering, even though it is quite common among bathroom users to

shave and shower at the same time. Users are forced to groom at the sink and travel to the shower

for showering. Similarly, many people, including those who catheterize themselves, seek access to the

sink when using the toilet. This access is denied because of the fixtures’ distant placement. The task-

oriented fixture design approach has produced distinctly different products that do not relate well

to one another. Unlike the machines for contemporary industrial production, these fixtures do not

interface well with one another, and bathroom activity requires time, movement, and effort. This may

be fine for most people, but it can be very demanding for many others. Fixtures that allow perform-

ing multiple and related tasks can produce improved bathroom environments and provide significant

benefits for everyone. Better fixture design will diminish time in the bathroom, reduce unnecessary

movement, and benefit not only people with disabilities, but also many other user groups. Everybody

will benefit from well-designed fixtures.

30.6 CONCLUSION

The future of the universal bathroom lies in recognizing that smart technology can ease bathroom

use and add convenience to daily living for everyone. The successful universal bathroom will employ

smart digital technology to establish communication within and between fixtures, so the bathroom

environment would adapt to users and not the other way around. For example, smart technology in

the IDEA Center’s movable fixtures bathroom has the potential to make instantaneous fixture adjust-

ment for stature variations, and to move them for better bathroom layout and fixture relationships. By

activating coded information, it is possible for digital technology to customize the movable fixtures

bathroom to suit people’s individual and collective needs. Better integration of smart technology

in the bathroom will increase convenience, eliminate unnecessary human intervention, facilitate

hygiene maintenance, produce improved bathroom environments, and offer significant benefits for

everyone.

30.7 BIBLIOGRAPHY

Design Continuum, Inc., “The Metaform Personal Hygiene System: Universal Accessibility,” Boston, MA,

2000.

Dychtwald , K., The Age Wave: How The Most Important Trend of Our Time Can Change Your Future. Published

by Sage Publication, 1990.

UNIVERSAL BATHROOMS 30.9

Mullick, A., “Universal Bathroom Design,” unpublished report to the National Institute on Disability and

Rehabilitation Research, 2000.

Singer, L. (ed.), A Bathroom for the Elderly, Blacksburg, Va.: Virginia Polytechnic Institute, 1988.

30.8 RESOURCES

Bakker, R., Elder Design: A Home for Later Years, New York: Penguin, 1997

Bath Ease, http://www.bathease.com/be_main.html.; 2010.

Bathroom safety checklist, http://www.google.com/search?hl=en&source=hp&q=Bathroom+safety+checklist&

aq=f&aqi=&aql=&oq=&gs_rfai=;2010.

Parents-Care; http://www.parents-care.com/pdf/elderly_bathroom_safety_free_checklist.pdf.; 2010.

Leibrock, Cynthia, “Kohler UD Bathroom” (video); http://www.kohler.com/video/index.jsp?bcpid=823619074&

bclid=1803311448&bctid=647738275; 2010.

Mullick, A., “Bathroom Lifts,” Buffalo, N.Y.: Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Design, University

at Buffalo, 1993.

———, “Bathroom Seats and Benches,” Buffalo, N.Y.: Center for Inclusive Design and Environmental Design,

University at Buffalo,1993.

Steinfeld, E., and S. Shae, “Accessible Plumbing,” technical report, Buffalo, N.Y.: Center for Inclusive Design

and Environmental Design, University at Buffalo, 1994.

This page intentionally left blank

CHAPTER 31

UNIVERSAL DESIGN OF

AUTOMOBILES

Aaron Steinfeld

31.1 INTRODUCTION

In most North American cities, automobile transportation is the means by which most people travel

when trips are too far to walk. The basic fact is that people with disabilities and older drivers will

need to use automobiles for the foreseeable future (Schieber, 1999), and automobiles are especially

critical for rural residents due to the general lack of transit. Lack of mobility within the commu-

nity corresponds to lack of access to employment, social interaction, and daily activities such as

shopping and entertainment. This chapter examines the major issues related to universal design of

automobiles.

In recent years, increased attention to applying universal design to automobiles has been moti-

vated by awareness of the aging of populations in developed countries and the impact that this

demographic shift will have (Waller, 1991). While the term universal design has not been popular

in the automotive industry, there is interest in the subject. This language gap reflects an underlying

ambivalence about addressing the needs of older people and people with disabilities directly. Too

close an association with aging and disability has been perceived as a marketing liability, particularly

if such features conflict with styling goals.

Despite their ambivalence and priorities, companies in the industry are now aware that the dis-

ability community and older adults are a growing consumer force. Some responses have been made

in recent years. Modifications include the use of tools such as the “Third Age Suit,” which allows

designers to experience the limitations in performance associated with aging and makes them more

sensitive to the impact of aging on driving and riding experiences (Block, 1999). Other automobile

companies have similar efforts underway (Parker, 1999). Unfortunately, most developments in

universal design of automobiles focus on interiors and have not addressed conflicts with structural,

aerodynamic, performance, and stylistic design goals.

31.2 PHYSICAL ASPECTS

Limitations in motor abilities cause significant problems in entering and exiting vehicles for both

drivers and passengers (James, 1985). About 50 percent of one large sample of the frail older popu-

lation reported difficulties getting in and out of vehicles (Steinfeld et al., 1999). Vehicles with high

floors are more common nowadays, and senior citizen transportation services frequently use vans

and minivans. Many older adults have difficulty getting in and out of these vehicles. Another popular

style is the sport coupe that is usually styled to look sleek and low. These require enough agility to

31.1

31.2 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

bend the body under low ceilings and to rise up out of very low seats. This problem, combined with

wheelchair access, has led the Vehicle Production Group (2009) to focus on a new vehicle design

called MV-1 that supports easy entry and egress by all passengers. The vehicle includes a low floor,

retractable wheelchair ramp, and a dedicated wheelchair parking area in the main cabin.

Back seats with narrow doors are impossible for many older passengers to use, and the rear seats

of two-door models are particularly difficult for older frail people to use. Drivers who use wheel-

chairs and can transfer on their own, on the other hand, find that two-door models are best for enter-

ing and exiting and loading and unloading their chairs. The doors of these models are very wide, and

having only one door on each side makes it possible to get the chair into the rear of the automobile.

Models with small rear-hinged doors behind the driver’s seat are also popular.

Seating and positioning play major roles in supporting driving tasks. The size of the “useful field

of view,” the “spatial area within which an individual can be rapidly alerted to visual stimuli,” has

been linked directly to accident frequency and driving performance in the older population (Owsley

and Ball, 1993). Consumers in focus groups reported using cushions to prop themselves up to get

a better view of the road (Steinfeld et al., 1999). Positioning also affects interaction with roadside

devices and tollbooths. Limitations in range of reach or grasping strength can make it very difficult

or impossible to use drive-in banking or restaurants. One solution is electronic toll collection. These

wireless payment systems were originally designed to increase efficiency at tolls, but also have sig-

nificant benefit to people with upper limb impairments.

Safety restraints have also been identified as a major problem. People over 55 who had been in

accidents have a significantly higher proportion of deaths even though a higher proportion of the

older group used seat belts (Cushman et al., 1990). One proposed explanation is that the incidence

of inappropriate use of seat belts by older people is much higher than that in the younger popula-

tion. Older people with disabilities have reported not using seat belts or moving the shoulder belt to

a different location because the belts are uncomfortable or cause pain (Steinfeld et al., 1999). The

difficulty of acquiring, moving, and buckling the belt was also a common complaint due to arthritis

and limitations in range of motion. Participants also identified the location of controls for adjusting

seat position as a problem. Many automobiles have the control lever located under the front edge of

the seat. Participants reported that this position was very difficult for them to reach.

Recommendations Box 31.1 Physical Design

• Accommodate passengers with mobility impairments by reduced fl oor height, high door

openings, and wide doors.

• Seats should be high enough to reduce the need to extend legs and reduce the need to

push up while exiting and bend down while entering.

• Include adequate handholds and consider improving access by designing new seating

systems such as swivel seats.

• Seating controls should be easy to understand and operate. Whenever possible, controls

should be located in a visible and easy-to-reach location.

• Roadside devices and tollbooths should be designed to accommodate drivers with limited

reach and upper limb mobility.

• Seat belt buckles should be located and designed so that they can be easily found and

fastened by people with limited upper limb mobility without favoring one side of the

body.

31.3 CASE STUDY: LEAR TransG

Lear Corporation, a major supplier of interior components to the global automobile industry, devel-

oped a concept interior that demonstrated how seating, instrument panels, environmental controls,

and window and door controls can be made more usable for older people (Fig. 31.1). Lear called

UNIVERSAL DESIGN OF AUTOMOBILES 31.3

their concept interior the “TransG” for transgenerational. It had features such as swiveling power

front seats, enhanced graphic display of instruments, and a storage cart that could be stowed in the

trunk.

The seats rotated out at a 45° angle to facilitate getting in and out and reduced dependence on

good balance or strength. The integrated seat belts had a four-point arrangement with a center-positioned

buckle that was easy to latch and see. This design made the act of fastening the belt much easier for

people with limited dexterity or a limited range of head movement. They secured the occupant more

uniformly and were more comfortable. The TransG instrument pod and pedals moved toward and

away from the driver rather than having the seat move. A memory control automatically adjusted

the seat, instruments, and pedals for each user. The floor of the concept interior had a lower step-up

height and a flat load floor to enhance ease of ingress and egress.

FIGURE 31.1 Lear TransG interior.

Long description: Two photos of the Lear TransG concept car. The

doors open at each end of the passenger compartment so that there is

a lot of room to enter and egress the vehicle. The seats rotate toward

the opening for even greater mobility. The steering wheel and instru-

ment cluster is designed to support reduced vision.

31.4 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

31.4 PERCEPTION OF THE ENVIRONMENT

Aging, sensory disabilities, and in-vehicle factors such as loud car radios all can result in impaired

perception of the surrounding environment. For example, when distracting stimuli are present, older

drivers can exhibit reduced performance with respect to visual field size, dynamic visual acuity,

velocity estimation, as well as other perceptual and cognitive factors (Hakamies-Blomqvist, 1996).

The effects of multiple disabilities exaggerate limitations in performance. These drivers can have a

reduced ability to detect horns, emergency vehicles, and other unusual events. Parabolic rear-view

mirrors can sometimes help.

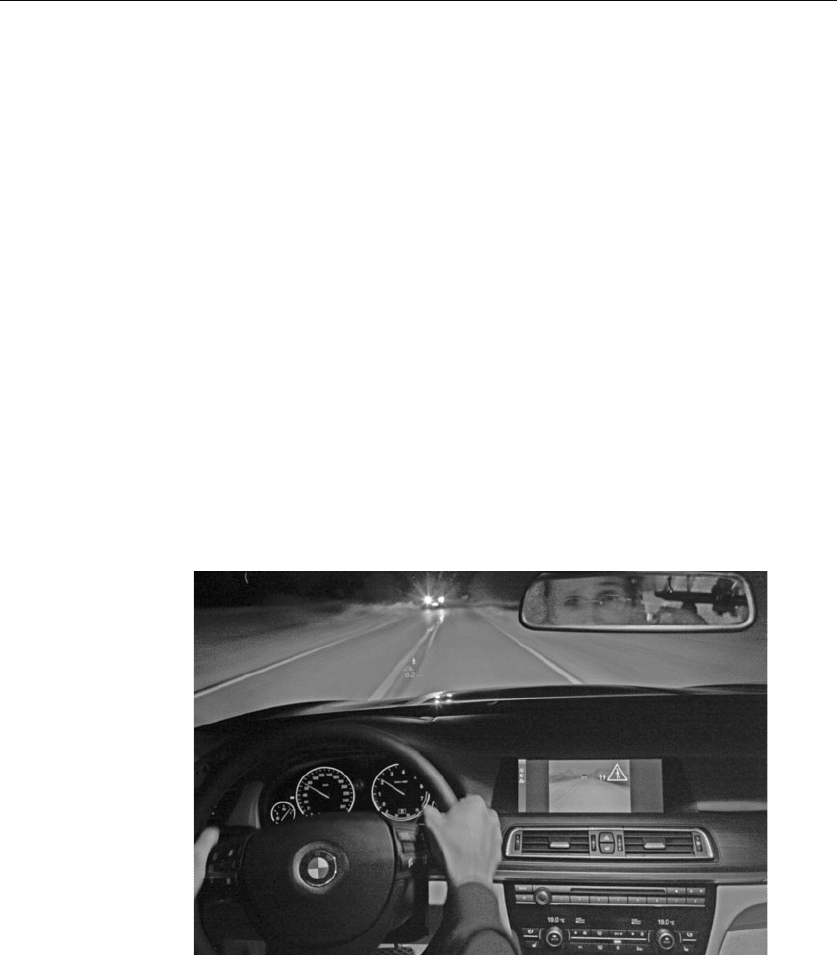

Night vision aids (Fig. 31.2) are particularly attractive to drivers who have impaired night vision.

As such, it is possible that older drivers who, in the past, were unwilling to drive at night may begin

doing so without any increase in risk. However, it is also quite possible that they may make matters

worse. These systems provide only monocular views to the driver, thus reducing depth perception.

Furthermore, night vision systems do not provide images that look normal, and drivers are still sus-

ceptible to glare from oncoming vehicle headlamps.

Head-up displays (HUDs) are sometimes attractive to vehicle designers, because they provide

a means to superimpose visual information on the road scene. Experiments involving HUDs have

shown promise, but there are serious perceptual and cognitive issues that need further research

(Tufano, 1997).

One technology that is particularly promising for drivers who have limited neck motion is the

parking aid. Parking aids include rear proximity sensors and other parking collision avoidance

systems (e.g., Ward and Hirst, 1998). These systems typically utilize audible backup warning alerts

when an object is detected. There is anecdotal evidence that such systems reduce mirror use, so

rear-camera systems may be more appropriate, especially due to the poor performance of many

noncamera systems (National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2006).

FIGURE 31.2 BMW night vision system. (Courtesy of BMW NA.)

Long description: A demonstration of the BMW night vision system. There are two pedestrians

in the forward scene. They are hard to see since the picture is taken at dusk. The center console

of the vehicle shows a thermal view of the forward road, and the pedestrians are clearly visible

as white silhouettes.

UNIVERSAL DESIGN OF AUTOMOBILES 31.5

31.5 NAVIGATION

As drivers age, some begin to lose their confidence and/or ability to navigate in unfamiliar territory.

If they acknowledge this difficulty, these drivers only drive on very familiar routes. Thus, in-vehicle

navigation systems are attractive as a means to compensate for poor or impaired way-finding abili-

ties. The user interfaces of most navigation systems are small, flat-panel displays mounted on the

dashboard. Audible directions are included in some systems, and HUDs are being examined as

alternative display devices. Interaction problems can include difficult destination input methods

(Steinfeld et al., 1996), visual attention conflicts, and poor understanding of imagery. The most

serious problem is misinterpretation of instructions. For example, in a real-world experiment of one

system there were four critical incidents in which subjects changed lanes upon instruction from the

system without checking for other cars (Katz et al., 1997).

Clearly, it is important that such technologies not distract drivers or overload their mental capa-

bilities. While systems that use speech output have limited visual impact, they exclude people with

hearing impairments unless visual information is also provided. The task of selecting choices and

commands can also distract the driver. Voice recognition systems are often heralded as the saf-

est input method, but they should be usable for individuals with speech impediments or accents.

Multiple language capabilities are also desirable.

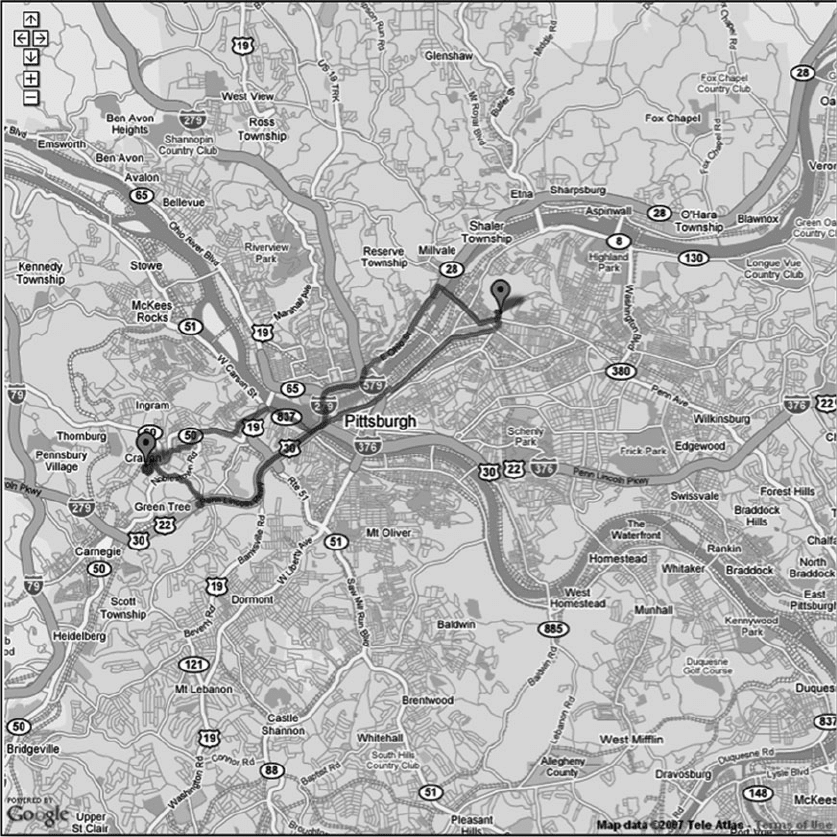

31.6 CASE STUDY: PERSONALIZED NAVIGATION

Current navigation systems offer limited customization of routing preferences and lack robust desti-

nation and route prediction capability. In an ideal case, systems would learn a person’s preferences

and predict desired destinations with minimal input. The former is especially important for drivers

who avoid certain types of intersections and road types (e.g., highways, roundabouts, etc.); the latter

cuts down on data entry and distraction. These features can also support dynamic rerouting based on

prior habits. For example, someone may avoid certain roads during rush hour but favor them at other

times. The system would know this and reroute accordingly. See Fig. 31.3. Research on this front is

advancing considerably, and good results are starting to appear (e.g., Ziebart et al., 2008).

31.7 SAFETY

Crash protection, or “occupant packaging” features, such as airbags and passive restraint systems

will not be addressed here. This subject is heavily studied by a variety of laboratories and tracked by

government agencies. Instead, the focus here is on high-tech, precrash safety developments.

Collision warning systems have been on the market but have mostly been installed on com-

mercial trucks. These systems use forward sensors to determine the presence and trajectories of

potential obstacles. A user interface indicates to the driver when dangerous scenarios exist, thus

prompting corrective action. When tied to cruise control, the vehicle can automatically respond to

forward obstacles by releasing the accelerator, shifting to a lower gear, and/or activating the brakes.

This functionality is referred to as adaptive cruise control and is an option on some luxury cars and

Recommendations Box 31.2 Perception

• Ensure that the introduction of new technology does not introduce side effects with

negative safety impacts that outweigh the benefi ts.

• Whenever possible, systems should provide redundant information in alternative

sensory modalities.

31.6 PUBLIC SPACES, PRIVATE SPACES, PRODUCTS, AND TECHNOLOGIES

commercial trucks. While these systems will likely improve safety for the general public, their cost

is high and some design questions remain.

Some precrash warnings use both visual icons and audible tones. This redundancy is good, since

using only audible signals does not provide sufficient information to drivers with impaired hearing.

Approaches involving haptic sensations and vibration have been used to transmit safety-critical

messages to the driver. The tactile modality is more direct and, like hearing, does not necessarily

depend on selective attention to convey a message. However, there are some concerns that drivers

will misinterpret such signals as maintenance problems.

FIGURE 31.3 Personalized routing based on a learned preference (route that avoids left turns goes around the block occasionally).

Long description: A screenshot of Google Maps showing two different routings between the same endpoints. One has fewer left turns than

the other.

UNIVERSAL DESIGN OF AUTOMOBILES 31.7

31.8 IN-VEHICLE INFORMATION

Consumers are expecting increasingly more complex information and entertainment options.

Unfortunately, the addition of these features can lead to “button overload” and the potential for

unsafe distraction while making selections. This has led to multifunction interfaces that integrate

many in-vehicle features through a limited set of buttons and selections using a “menu tree” (Sumie

et al., 1998). This supports a reduction in buttons and use of simpler interfaces, larger buttons, larger

text, and more logical grouping of functions. However, the tradeoff could be a longer selection

period and additional glances to the dashboard. The need to switch visual attention several times

between the road and the dashboard is problematic for all drivers, especially older adults. Older eyes

require more time to refocus, as attention shifts from a distant object (road scene) to a close object

(control panel).

The main problem with many in-vehicle devices is that they are not accessible to people with

hearing impairments. Some may argue that this is good since there are fewer potential distractions,

but there are significant benefits for some of the features. For example, radio reports of traffic con-

gestion or hazardous weather are immensely beneficial. Besides the time saved by route alterations,

there is a safety benefit because advanced warning of congestion or weather leads to higher levels of

alertness. Text-based alerts are useful to hearing-impaired drivers who have good eyesight, but small

text may lead to difficulty for older drivers. Finally, the lack of entertainment beyond basic driving

tasks during long trips can lead to increased boredom for drivers who cannot hear music or other

audio entertainment due to a lack of mental stimulation.

Recommendations Box 31.3 Safety

• System functionality should be easy to understand.

• Alerts and other interfaces should utilize redundant sensory modalities in a standardized

manner.

Recommendations Box 31.4 In-Vehicle Information

• Provide redundant information in a form accessible to drivers with hearing impairments

whenever possible.

• Activities that require high cognitive demands should be permitted only when the

vehicle is not in motion, or safeguards should be provided to only permit passenger

use while in motion.

31.9 POLICY

One area that could benefit from novel applications of universal design is policy. Many licensing

approaches lack appropriate attention to managing the middle ground between driving and not driv-

ing. Some states have restrictions for younger drivers based on time of day, but do not support similar

restrictions for other drivers based on capability. Likewise, some states explicitly prohibit license

restrictions based on location. Drivers who have trouble on highways or in unfamiliar areas are

forced to relinquish their license for driving scenarios they intentionally avoid. Geographic restric-

tions would permit continued independence and mitigate fear of losing one’s license when consid-

ering driver rehabilitation. This lack of a managed progression from driving to no driving results

in disruptive lifestyle changes and loss of quality of life. Insurance companies have entered this

discourse, exploring concepts such as lowering rates if the driver submits to monitoring. These same

monitoring concepts could be utilized to support managed independence in this middle ground.