Morris & Fan. Reservoir Sedimentation Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.15

The source of these discrepancies is probably related to measurement problems in 1987,

which contributed most of the computed sediment inflow during two sparsely sampled

storm events. The bathymetric and fluvial estimates of trapped sediment agree rather

closely if the 1987 fluvial data are discarded. This illustrates the potential difficulty in

measuring sediment yield in flashy streams.

20.3.5 Trends in Sediment Yield

Reforestation and erosion control have long been proposed for sediment management in

Puerto Rico. At the time of Spanish occupation in 1508, the entire island was forested,

but by 1828 forest cover had been reduced to about 66 percent of the island's area

(Wadsworth, 1950). Forest inventories summarized by Birdsey and Weaver (1987) show

that the total forested area in Puerto Rico had declined to a low of 12 percent of the

island's area in the late 1940s, with about half of this area being shade coffee plantings.

This dramatic denudation of forest area reflected the extensive cultivation of steep

erodible hillsides either by hand or by oxen, a practice that was commonplace into the

1960s. Erosion from steep hillside farms has been a major source of erosion contributing

to reservoir sedimentation (Noll, 1953). Improving economic conditions since the 1950s

led to the gradual abandonment of hillside farming and reforestation of the slopes. By

1984, forest cover of all types, including areas of shade coffee production, covered 34

percent of the island. Most of the increase in forest cover occurred in the island's steep

interior area, where most hillside farms have been abandoned and are in secondary forest

or pasture. During this same period, urban development has focused primarily on the

coastal plain, largely bypassing the watersheds tributary to reservoirs, with the notable

exception of the Loíza watershed, which had a 1990 population density exceeding 500

persons/km

2

.

Given the small steep watersheds, gravel bed rivers, predominance of easily

transported fine-grained sediment, and the limited opportunity for and evidence of

sediment deposition on the narrow valley floors above most reservoirs, the sediment

delivery ratio is expected to be very high. Under these conditions a significant decline in

erosion due to the abandonment of hillside farms and dramatic increase in forest cover

would be expected to produce a noticeable, if not dramatic, decline in the rate of reservoir

storage loss, except possibly in watersheds affected by extensive sediment-producing

construction activity.

The longest continuous fluvial sediment record in Puerto Rico (1968 to present)

monitors discharge and load from the 47.7-km

2

Rio Tanama watershed on the north

coast. No trends are evident in this dataset based on construction of a double mass curve

of water and sediment. Longer-term trends in sediment yield may be analyzed using

reservoir resurvey data. Repeated bathymetric survey data are available at only a few

sites in Puerto Rico. Data from Loíza and Dos Bocas reservoirs, both on the island's north

coast and with similar watershed sizes, reflect contrasting trends in sedimentation (Fig.

20.13). The Dos Bocas watershed has experienced extensive reforestation and relatively

little urban development, yet there has been no apparent decline in the rate of sediment

accumulation. In contrast, the Loíza basin has experienced considerable urban expansion,

including both housing and highway development on sloping soils with virtually no

erosion control practices. (See Figs. 12.4 and 12.13.) Nevertheless, the Loíza data show

an apparent decline in sediment yield as a function of time: the rate of reservoir storage

depletion averaged 0.418 Mm

3

/yr from 1953 to 1971, but only 0.175 Mm

3

/yr from 1971

to 1994. It is not clear to what extent this reflects differences in hydrology; there has not

been a major flood in the Loíza basin since October 1970, whereas Dos Bocas

experienced a large flood in 1985.

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.16

20.4 SCREENING OF SEDIMENT CONTROL STRATEGIES

Sediment management activities were initiated by compiling the available data and

conducting a screening analysis to identify the most feasible control options.

20.4.1 Reservoir Replacement

Can Loíza Reservoir be replaced? The existing dam occupies the only feasible dam site

on the main stem of Rio Loíza. The two main tributaries, Loíza and Gurabo, join at the

upstream limit of the impoundment, and proposed dam sites further upstream above the

valley floor would control only a small fraction of the total watershed tributary to the

existing dam. There is limited opportunity to raise the pool elevation because it would

increase flood hazard to upstream urban areas, and with the base of the dam only 15 m

above sea level and extensive urbanization downstream, there is little opportunity for a

new downstream site. Other existing and potential reservoir sites are found elsewhere on

the island, but, in addition to development costs they would incur, these alternative sites

would eventually face sedimentation problems. Furthermore, both the Loíza and La Plata

watersheds are ideally located from the standpoint of supplying water to San Juan, and

the entire water treatment and distribution system has been developed from these two

points of supply.

A new water supply with an ultimate firm yield of 4.4 m

3

/s (100 mgd) is being

developed from the existing Dos Bocas and Caonillas hydropower reservoirs in the

Arecibo watershed, 60 km west of San Juan. However, Rio Arecibo does not have

enough water to allow existing reservoirs to be abandoned, and sedimentation is also a

problem in the Arecibo reservoirs. Dos Bocas Reservoir, impounded in 1942, and

Caonillas Reservoir, impounded in 1948, have respectively lost 43 and 12 percent of their

capacity to sedimentation. Using and then abandoning reservoir sites is not a sustainable

water supply strategy in Puerto Rico.

20.4.2 Upstream Sediment Detention Basins

Sediment trapping at upstream detention basins was considered, but the combination of

fine sediment sizes and high discharges would require large basins. Further, sediment

trapping is only a temporary measure unless combined with sediment removal, and

sediment removal from the reservoir would probably not be materially more difficult or

costly than removal from detention basins. Given the high cost of land and high

population density, upstream sediment trapping was considered infeasible.

20.4.3 Sediment Flushing

Full drawdown of the reservoir for flushing was considered infeasible without costly

structural modification to the dam because of the lack of bottom sluicing capacity. It is

also incompatible with the requirement to maintain the reservoir in continuous service to

provide water for San Juan. Finally, there is no possibility of obtaining environmental

permits for reservoir flushing at this site.

20.4.4 Venting Turbid Density Currents

Turbidity current venting was not considered a viable option. Preliminary computations

indicated that Loíza Reservoirs was to shallow to generate flow stratification during

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.17

major events, although smaller freshets can plunge upon entering the reservoir. Also,

low-level outlets were too small and the broad flat deposits are not conducive to

maintaining density current motion.

20.4.5 Explosive Mobilization

The use of explosives to mobilize sediment so it would be carried away during floods

was considered, as described in Sec. 16.3.6. However, there were too many uncertainties

associated with this technique for it to be considered. One important problem was the

possibility of leaving explosive material in place for a period of more than a year if a

flood did not occur during the target wet season.

20.4.6 Sediment Pass-Through

Loíza Reservoir is highly elongated, and the 10-m-tall radial gates control virtually the

entire useful storage pool, suggesting that sediment pass-through may be feasible. The

reservoir has always been operated to maintain the highest possible pool level to ensure

adequate water supplies, thereby maximizing both detention time and sediment

deposition within the impounded reach. However, if the dam's radial gates are fully

opened during flood events, the reservoir will behave like a river, producing high flow

velocities which minimize the deposition of fine sediments. The original usable reservoir

capacity of 20 Mm

3

is smaller than the volume of the major storm events that deliver high

sediment loads (Fig. 20.8). This pointed to the possibility of opening the reservoir's gates

at the onset of a storm event, allowing the flood to pass through the impounded reach at

high velocity, and closing the gates to refill the impoundment with the volume contained

in the recession portion of the hydrograph. Sediment pass-through was selected as a

prospective management strategy at Loíza Reservoir.

20.4.7 Dredging

Sediment pass-through at Loíza Reservoir is not expected to remove previously deposited

sediment and will not be effective in transporting coarse sediment beyond the dam.

Sediment removal is required to recover and maintain storage capacity. Dry excavation is

not considered feasible because the reservoir needs to remain in service. However, even

if the reservoir could be withdrawn from service, dry excavation would still not be

feasible because: (1) draining the reservoir would create flushing conditions with

unacceptable downstream environmental impacts, (2) the poorly consolidated fine

sediment deposits in the submerged river channel, which comprise the majority of the

deposits, are poorly suited to dry excavation, and (3) with only 1.1-m-diameter low level

outlets, the work area in the reservoir would be inundated by even small runoff events.

Thus, hydraulic dredging was the only option considered feasible.

20.5 MODELING OF SEDIMENT ROUTING

The HEC-6 sediment transport model (U.S. Army, 1991) was used to quantify the

effectiveness of sediment routing (Morris and Hu, 1992). Loíza Reservoir has highly

one-dimensional geometry, and HEC-6 was the only U.S. model capable of handling the

full range of grain sizes important at this site, sand through clay. Two models were con-

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.18

structed. One model simulated the reach from the dam upstream for a distance of 14.8 km

along the Loíza River, plus a 5.2-km-long branch along the Gurabo River. This covered

the impounded reach, extending approximately 9 km upstream of the dam, plus the

riverine reaches between the pool and the two gage stations. The second model covered

the reach between the ocean and the dam, a distance of 28 km, and was oriented to

addressing environmental issues related to the possible settling of material from the

reservoir into the downstream river and riverine estuary. Modeling indicated that down-

stream deposition should be insignificant for any grain size transported past the dam.

20.5.1 Inflow Hydrographs

An inflow hydrograph containing time steps ranging from one day during high-flow

periods to 30 days during low-flow periods was developed from the 30-year record of

average daily streamflow at the Loíza and Gurabo River gage stations. The one-day time

step matched the shortest time interval for which published sediment load and discharge

data were available from the USGS.

20.5.2 Sediment Characteristics

A rating curve specifying the total daily sediment load and its grain size characteristics as

a function of daily discharge was developed from the 5-year record of daily sediment

load. This relationship was then applied to the entire 30-year gage record. The percentage

of sediment in each of the size classes was specified to vary as a function of discharge; at

low flow all inflowing sediment was specified to be of clay-sized particles, whereas at

high flows coarse silts and sands become more important. The initial grain size

distribution of the bed within each reach of the model was specified by using data from

shallow gravity cores in the reservoir plus bed material samples from the Loíza and

Gurabo Rivers above the reservoir.

20.5.3 Model Calibration

The model was calibrated by simulating the historical deposition pattern and grain size

distribution in the reservoir. Calibration analysis could not be started from the original

(1953) reservoir bathymetry because streamgaging did not start until 1959. Therefore, the

calibration analysis was initiated with the 1963 bathymetry and was run until 1985 using

the gage station discharge data and the rating curve, and the resulting deposition pattern

was compared to the 1985 bathymetry. It was initially not possible to match the 1985

bathymetry, but when the 1990 bathymetry became available several months after these

simulations were performed, it was discovered that the 1985 bathymetry was erroneous

and the model was successfully calibrated to the 1990 data.

Initially the model underestimated clay deposition. A similar problem had been

encountered with the HEC-6 model at the Martins Fork Reservoir (Martin, 1988).

Settling tests conducted with native water demonstrated the presence of strong

flocculation that caused the clay fraction to settle at velocities more typical of silts. The

program code was modified to allow the clay settling rate to be user-specified, and

excellent calibration results were achieved using the modified model and 1990

bathymetry. Historical deposition patterns were matched very closely in terms of both the

deposit pattern and the average grain size distribution in the reservoir deposits obtained

from the shallow cores (Fig. 20.14).

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.19

FIGURE 20.14 HEC-6 model calibration at Loíza Reservoir. Model results are shown as soli

d

squares (Morris and Hu,1992).

20.5.4 Modeling Results

The bed shear stress profile along the reservoir for a discharge of 708 m

3

/s (25,000 ft

3

/s)

is shown in Fig. 20.15, which compares high-pool (historical) operating conditions

against low-pool (sediment pass-through). The pass-through operation increases bed

shear values by more than a full order of magnitude over much of the reservoir.

FIGURE 20.15 Bed shear stress along the impounded reach of Loíza Reservoir showing

the effect of sediment pass-through routing.

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.20

The impact of sediment pass-through on bed shear values decreases moving upstream

from the dam as the backwater profile becomes increasingly controlled by channel

friction along the narrow reservoir. However, successive bathymetric measurements

indicate that by 1990 the reservoir had already reached an equilibrium profile in the

narrow upstream reach, and most sediment was accumulating in the portion of the

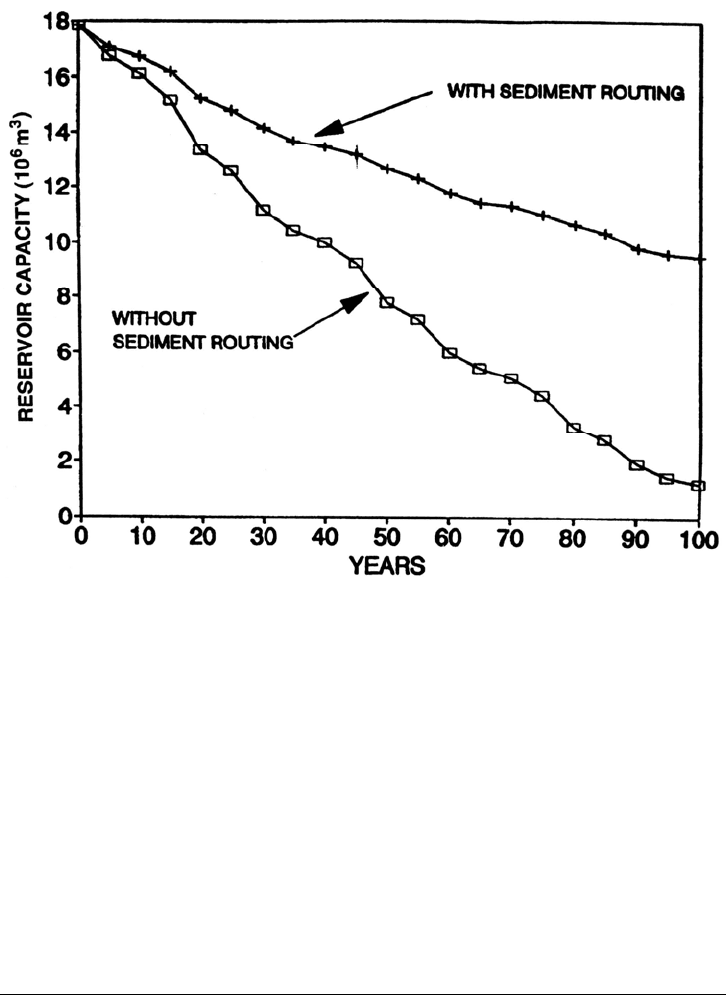

reservoir within about 4 km of the dam. One-hundred-year simulations indicated that by

changing the operating strategy from continuous high-pool operation to sediment pass-

through during flood periods will decrease sediment accumulation by 65 percent (Fig.

20.16). Sediment pass-through should be capable of transporting most flood-borne silts

and clays through the reservoir, but most sand-size particles will continue to be trapped,

as will fines delivered during small inflow events.

FIGURE 20.16 Effect of sediment pass-through routing in reducing the rate of sediment

accumulation.

20.6 OPERATIONAL MODEL

20.6.1 Operational Constraints

Implementation of sediment pass-through at Loíza Reservoir is complicated by several

operational constraints. The tributary watershed is small and steeply sloping, and peak

runoff will reach the dam within several hours of the receipt of rainfall in the watershed.

Although Loíza Reservoir is too small to have significant flood control benefits, there are

flood-prone communities downstream of the dam and it is essential that reservoir opera-

tions not increase flood damage above levels which would have occurred in the absence

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.21

of the dam. On at least one previous occasion, gate operation at Loíza Dam magnified

discharge below the dam during a runoff event by, releasing water faster than it entered

the reservoir, causing downstream flooding that would not otherwise have occurred.

Because of the downstream flooding hazard, releases from the reservoir should not

exceed bankfull capacity of about 1700 m

3

/s unless reservoir inflow exceeds this amount,

in which case reservoir discharge should not exceed inflow. The bankfull capacity is

variable and depends on the sandbar configuration at the river mouth where it discharges

to the Atlantic Ocean, and adjacent to the flood-prone coastal community of Loíza Aldea.

The river mouth becomes completely blocked with beach sand during dry periods, and

releases should be made from the dam as early as possible to wash out the river mouth

bar. Maximum sediment routing effectiveness also requires the earliest possible reservoir

drawdown, to the lowest level possible, and for the longest duration possible. Early

release of water from storage is critical because the rate of reservoir drawdown is

determined by the difference between discharge and inflow. As inflow increases, the

drawdown rate must decline to prevent downstream flooding, and, when inflow exceeds

downstream bank full discharge, the reservoir level cannot be lowered further because it

would require that discharge exceed inflow. It is also essential to completely refill the

reservoir at the end of the flood for the water supply.

20.6.2 Model Development

A sediment routing system was developed within these constraints by using the sediment

pass-through strategy based on hydrograph prediction outlined in Sec. 13.4 and Fig. 13.6.

All modeling was implemented in a 386 25-Mhz microcomputer. Prediction of the 24-

hour storm runoff hydrograph from tributary areas and hydraulic routing through the

reservoir was undertaken with the BRASS model (Morris et al., 1992). This model was

used to forecast the total water volume tributary to the dam consisting of: (1) the runoff in

the tributary watershed which has not yet reached the reservoir, plus (2) the water volume

in the reservoir.

The BRASS model was originally developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

(1981) and has been described by McMahon et al. (1984) and Colon and McMahon

(1987). The model includes a hydrologic module and a hydraulic module which

incorporates the DWOPER (Dynamic Wave Operational) one-dimensional unsteady flow

hydraulic model, which solves the St. Venant equations. Originally designed to operate at

1-hour intervals, the model was modified to use the 15-minute time increment needed to

simulate the response of the relatively small and steep Loíza watershed. Another

modification allowed reporting of the total water volume above the dam in both the

hydrologic and hydraulic modules. The DWOPER model was used to perform hydraulic

flood routing through the river-reservoir reach instead of a hydrologic flow routing

method because highly variable flow conditions may occur in the reservoir over a storm

period. Within hours, a reach may alternate from impounding to free flow to impounding

again because of early drawdown, passage of the flood, and subsequent refilling.

The model predicts runoff hydrographs based on the Soil Conservation Service unit

hydrograph method which uses a soil "curve number" that is adjusted according to

antecedent moisture conditions. Real-time rainfall data are available from two

independent networks of reporting gages within the watershed. The primary data source

is the Enhanced ALERT (Automated Local Evaluation in Real Time) system, which

incorporates tipping bucket raingages and VHF radio telemetry. The USGS data

collection platforms, which also have tipping bucket raingages and report via satellite, are

available as backup telemetry.

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.22

The operational system delivered to the authority uses a customized BASIC language

system manager software shell which automatically reads and interprets program output

files. It includes graphical display of water surface and velocity profiles, discharge

hydrographs, summary data on reservoir and runoff volume, recommendations for gate

operation, and access to all program input and output options. The system manager was

programmed to compute the gate openings required to maintain the maximum

permissible discharge subject to the limited capacity in the downstream channel plus

water storage constraints. Gate operating limitations such as opening and closing speed

and out-of-service gates are incorporated. Hard copy reports and graphics can be printed

out during and at the end of the event. Multiple preprogrammed graphics display

parameters are provided such as gage status, rainfall intensity, water surface profile, and

observed and predicted hydrographs. The Spanish-language menu system allowed the

operator to manage the hundreds of program and data files contained in the system.

20.6.3 Model Input

For runoff computations, the watershed tributary to the dam was divided into 14

subbasins. Theissen polygons are drawn for each raingage, antecedent soil moisture is

calculated for the 5 days prior to a storm event, and curve number values for each

subbasin are adjusted accordingly. Each subbasin receives a weighted portion of the

rainfall reported by neighboring raingages, and the resulting discharge hydrograph from

each subbasin is computed and routed into the hydraulic model. The hydraulic model

contains 55 cross sections extending approximately 13.5 km upstream of the dam along

the Loíza River, and 4.7 km upstream along the Gurabo river from its confluence with the

Loíza river. The system is designed to operate in real-time based on rainfall actually

received at reporting raingages; computations are not dependent on rainfall prediction,

although the model is capable of predicting reservoir hydraulics from forecast rainfall.

20.6.4 Model Calibration

At the time of model construction, very few ALERT raingage data were available in the

Loíza watershed. Calibration was conducted with the only significant set of continuous

rainfall and discharge data available prior to June 1991, that for hurricane Hugo on

September 18, 1989. This was not a particularly heavy rainfall event and the 1800-m

3

/s

peak discharge at the dam had a return interval of under 5 years. Model calibration

focused on hindcasting three hydrographs: runoff hydrographs at the Gurabo and Loíza

gages, and the discharge hydrograph immediately below the dam. Extensive convergence

testing of the DWOPER model was undertaken, challenging the hydraulic module with

extreme fast-rising hydrographs and sudden opening and closure of gates, making

adjustments as necessary until the model was capable of continuous computation without

convergence error through events more extreme than those considered physically possible

in the watershed.

2.6.5 Model Operation

Periods of heavy rainfall across the Loíza watershed are associated with large-scale

weather systems such as tropical depressions and frontal systems which can be forecast

During these periods it is necessary to continuously monitor the total tributary volume of

water upstream of the dam. As rainfall is received in the watershed the total volume

tributary to the dam (predicted 24-hour inflow hydrograph plus reservoir storage) will

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.23

exceed the total reservoir storage capacity. When this occurs, it is possible to release

water from the reservoir with confidence that the reservoir can be refilled, as long as the

total tributary volume always equals or exceeds the total reservoir capacity. As the storm

continues to develop, drawdown can continue until the reservoir is fully drawn down with

all gates open and the water level at the dam is determined by weir flow over the gated

spillway. When rainfall diminishes, the gates are progressively closed to store water in

the reservoir. Thus, sediment routing procedures may be initiated at the beginning of all

significant rainfall events, and the extent of drawdown will be determined by the

magnitude of the storm that eventually develops. Simulations showed that the reservoir

can be completely drawn down with approximately 3 hours of lead time.

The hydraulic BRASS model has a limitation in that there is no opportunity within a

model run to adjust the reservoir volume using real-time field observations during an

event. An option is to continuously compute storage volume from reporting level gages at

different points along the reservoir instead of using a hydraulic model. Hydrologic

computations would continue to be performed according to the previously developed

methodology.

20.7 SEDIMENT REMOVAL

Sediment pass-through at Loíza Reservoir can substantially reduce sedimentation but

cannot prevent it. HEC-6 sediment transport modeling indicated that sands, which

constitute about 20 percent of the sediment load, will continue to be trapped in the

reservoir, and fines delivered during smaller runoff events will also be trapped. Sediment

removal is required to maintain reservoir capacity or to recover previously lost capacity.

Hydraulic dredging is both technically and economically feasible, but dredging alone as

the sole means to control future sedimentation is unnecessarily costly. As much sediment

as possible should be passed through the reservoir by sediment routing to reduce both the

economic and environmental costs of dredging, and to reduce dredging frequency.

Dredging options were discussed in the project environmental documents (PRASA, 1992,

1995).

20.7.1 Dredging Volume

Two types of dredging activities were analyzed: (1) maintenance dredging and (2)

restoration dredging. Maintenance dredging would focus in the upstream portion of the

reservoir where the existing deposits consist largely of sand-size particles. Approximately

2 Mm

3

of sediments would be removed by dredging, creating a trap to capture the coarse

fraction of the inflowing sediments which cannot be transported through the reservoir

during pass-through events, essentially stabilizing present reservoir capacity. It is

preferable to have these sediments accumulate in an area near disposal sites upstream of

the reservoir rather than to transport sediment into the main part of the impoundment.

There is a strong market for sand in Puerto Rico with prices in excess of $10/m

3

. An

additional consideration was the possibility of marketing sand trapped in this upper area

of the reservoir.

Restoration dredging would entail the removal of about 6 Mm

3

of material, returning

the active pool of the reservoir to near its original capacity. Sediments more than 2 m

below the invert elevation of the lowest water supply intake would not be removed and

most of the dead storage pool would remain sedimented. The restoration dredging alter

LOÍZA RESERVOIR CASE STUDY 20.24

native was preferred, since it would immediately create about a 0.26 m

3

/s (6×10

6

gal/day)

increase in firm yield and also produce the longest time interval before the next dredging.

20.7.2 Spoil Disposal Options

There are no easy disposal options at Loíza reservoir. Lands in the vicinity of the

reservoir are steeply sloping. Flat coastal lands between the dam and the sea are either

urbanzed, are protected wetlands, or have been designated as river floodway by the

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). The nearest potential downstream

land disposal site would require about 15 km of pipeline from the dam site. Use of this

site would also require a floodway revision in a hydraulically complex floodplain area.

Disposal to the Atlantic Ocean was considered and rejected under two different

options. One option would entail a pipeline to the coast extending offshore to a new

ocean disposal site to be designated. Another ocean disposal option would involve a

pipeline to a coastal site, where the sediment would be dewatered and transferred onto

barge which would dump it into the currently designated dredged material deep ocean

disposal site located in the vicinity of San Juan harbor. Both options would require a

pipeline in excess of 20 km long and would involve long permitting lead times.

Additionally, if an economically viable land disposal site is available, the U.S.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is not likely to grant an ocean disposal permit.

Upland sites upstream of the reservoir are available but again require rather long

pumping distances. The three disposal areas currently under consideration vary in

distance from 12 to 21 km from the dam (Fig. 16.11). Most sediment is deposited in the

wider portion of the impoundment within 3 km of the dam rather than the narrow

upstream reach, and over half the disposal volume occurs in the most distant disposal site.

In addition to pumping friction losses, the upstream disposal areas require static pumping

heads up to 30 m. The volume of dredged material will initially exceed that of in situ

sediment because of water entrainment. At Loíza Reservoir, containment area volume

requirements were estimated for initial bulking factors of 1.5 to 1.8 and a final bulking

factor of 1.2.

20.7.3 Sediment Sampling

A two-part sediment sampling program was undertaken in the reservoir to analyze the

possible presence of contaminants. A preliminary sampling and analysis program was

conducted on 19 sediment samples which were subjected to the elutriate and modified

elutriate analysis tests. These tests mix sediment with water to simulate the dredging

process, then allow the water to settle. The concentration of chemicals found in the

settled water simulates the quality of water that will be discharged from a dredged

material containment area. Supernatant filtration removes fine sediment and the

associated contaminants. This gives an indication of the fraction of the contaminants

associated with particulate material, and also approximates the quality of water that could

be produced if the undiluted containment area discharge were used to supply a potable

water filtration plant. The preliminary sampling and analysis program indicated that

concentrations of inorganics in the elutriate that exceeded water quality standards

included cadmium, cooper, chromium, lead, mercury, nickel, silver, zinc, and cyanide.

However, high concentrations were found only in the unfiltered elutriate samples,

indicating that the contaminants were associated with sediment particles and were not

generally present in dissolved form. It was concluded that removal of sediment from the