Morris & Fan. Reservoir Sedimentation Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

ENVIRONMENTAL AND REGULATORY ISSUES 18.29

18.5 MANAGEMENT OF COARSE SEDIMENT

Most dams, including those managed for sediment pass-through, continue to act as

efficient gravel traps. A continuous supply of gravels below the dam may be

required to prevent channel incision, and to maintain aquatic habitat and spawning areas.

Artificial means will usually be required to deliver gravel to the river below a dam.

18.5.1 Gravel Replenishment below Dams in California

When the transport of spawning-size gravels along a stream is interrupted by dam

construction, the gradual coarsening of the bed below the dam can reduce the areas

available for spawning. Artificial gravel-feeding techniques used in California have

been reviewed by Kondolf and Matthews (1993).

Ideally the gravel would be excavated from the deposition areas in the reservoir delta

and discharged below the dam. However, because delta deposits may be far from the dam

and lack good access, it may be less costly to obtain replenishment gravels from a

nearby quarry. Replenishment gravels should not be obtained from an active river

channel, lest gravel replenishment in the target river promote degradation in another

river.

The cost of gravel replenishment is highly sensitive to scale economies and the

proximity to an appropriate gravel source. Costs of gravel replenishment projects are

summarized in Table 18.2. The least costly procedure is to discharge gravel regularly at a

single site, replenishing the supply point as the gravel is transported into the downstream

reach by the river. An example of this type of gravel replenishment operation is

illustrated in Fig. 18.18. It is much more costly to replace gravel along an entire river

reach, which also involves impacts caused by access by heavy equipment along the

replenishment reach. When spawning habitat is to be maintained, the gravel emplaced in

the river should be free of fines or sands which impart turbidity and can clog spawning

beds.

18.5.2 Grain Feeding in the Rhine River

A series of 10 barrages have been constructed along the reach of the Rhine River

extending l7.5 km downstream from Basel, at the Swiss border, to Karlsruhe,

TABLE 18.2 Gravel Replenishment Projects in California

Reservoir and river Year Volume, m

3

Total cost, $ Unit cost, $/m

3

Camanche, Mokelumne River 1990 76 $ 20,000 $ 263

Camanche, Mokelumne River 1992 230 6,300 27

Keswick, Sacramento River 1988 76,410 250,000 3

Keswick, Sacramento River 1989 68,769 200,000 3

Los Padres, Carmel River 1990 612 82,000 134

Iron Gate, Klamath River 1985 1,666 136,000 82

Courtwright, Helms Creek* 1985 5 12,000 2,400

Trinity, Trinity River 1989 1,490 22,000 15

Folsom, American River 1991 764 30,000 39

Grant Lake, Rush Creek 1991 917 18,000 20

*At Courtwright, a helicopter was used to drop gravel into a narrow gorge by hopper.

Source: Kondolf and Matthews (1993).

ENVIRONMENTAL AND REGULATORY ISSUES 18.30

Germany. The first barrage was constructed in 1928 at the upstream end of this reach,

and the most recent and most downstream barrage, Iffezheim, was closed in 1977.

These barrages trap part of the suspended load and all the bed material load,

consisting of sands and gravels. Although the river flows freely below Iffezheim, its

course is fixed by a series of river training works, resulting in the gradual incisement of

the channel. Lowering of downstream water levels reduces navigation clearance at

the exit from the locks, and erosion of coarse bed material can expose finer-grained

underlying formations to scour, producing an irregular bottom profile. The

navigational depth along this reach of the Rhine is 2.1 m, plus only 0.4 m of

additional clearance to the bottom, and even slight scouring of the bed can change the

profile sufficiently to interfere with navigation.

Four methods were considered to stabilize the bed geometry below the Iffezheim

barrage: (1) continued construction of additional barrages farther downstream, (2)

continued construction of groynes, (3) bed armoring, and (4) artificial grain feeding.

While the first three methods could control bed erosion and water levels in the treated

area, the erosion problem would continuously reappear farther downstream and the

treatment area would need to be continuously extended. The first three alternatives

would also tend to interfere with easy and safe navigation, and would meet

environmental opposition. As a result, artificial grain feeding was initiated at

Iffezheim after its closure in 1977.

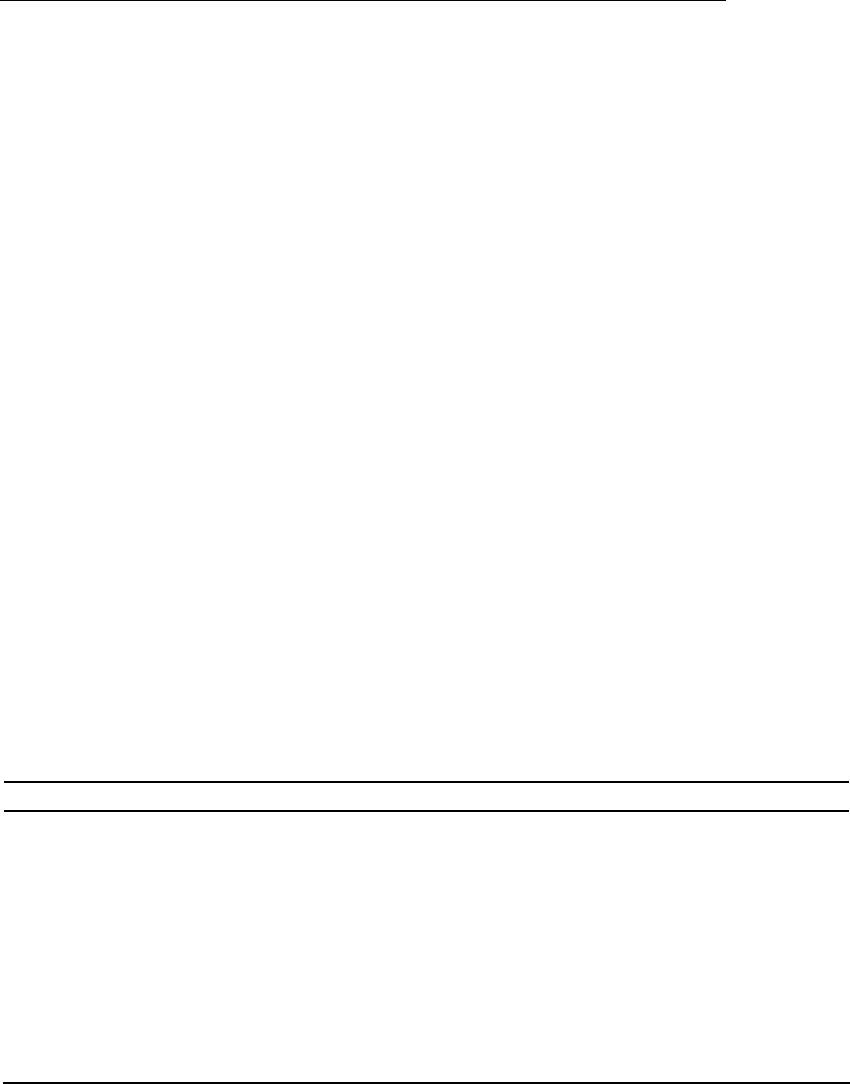

FIGURE 18.18 Gravel replenishment below Keswick Dam on Sacramento River, California

(Kondolf and Matthews, 1993).

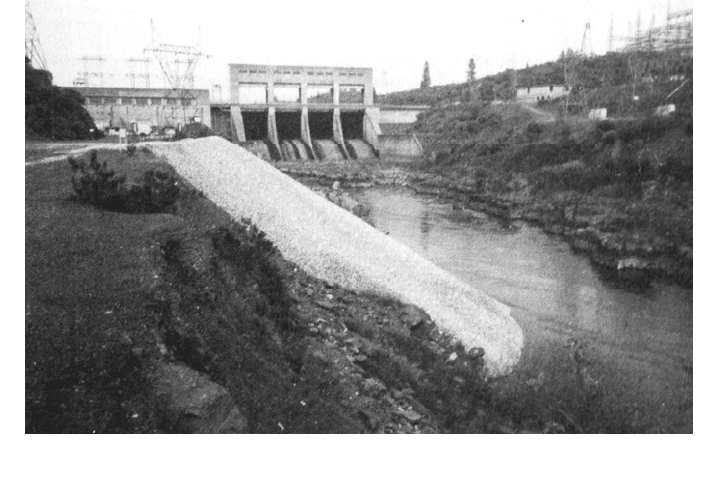

Grain feeding is conducted by excavating sands and gravels from a floodplain quarry

upstream of the barrage, which are placed onto a hopper-bottom scow that is locked

downstream. The bed material is discharged to the riverbed below the barrage by opening

the hopper bottom while the scow is traveling downstream at high speed, resulting

in a deposition pattern 50 to 300 m long and 10 to 20 m wide (Fig. 18.19). To

reduce travel distance, the gravel is obtained from a quarry near the lock rather

than being dredged from deposits near the upstream limit of the pool. On the

average, 150,000 m

3

of coarse material is deposited below Iffezheim each year. The

grain size is matched against the original material in the riverbed to allow the

continued downstream transport, and the rate is adjusted to maintain navigational

ENVIRONMENTAL AND REGULATORY ISSUES 18.31

clearance. Navigation conditions along the 18-km reach downstream of the dam are

monitored at 38 water level gages. Cross sections are measured daily in the area of grain

feeding, every fortnight in the 2- km reach below the feeding area, and annually in the

18-km reach below the barrage. Overall, about 6000 cross sections are measured each

year. The effect of grain feeding has been examined by both physical (Nestmann,

1992) and numerical modeling (Siebert, 1992).

Grain feeding has successfully stabilized the bed of the Rhine to date in the reach

immediately below Iffezheim, and it has not been necessary to construct additional

barrages downstream to maintain navigation depth (Kuhl, 1992). However, reaches

further downstream have not been stabilized by the gravel feeding at Iffezheim, and

additional grain feeding at downstream locations will probably be required in the

future to compensate for reduced delivery of bed material from regulated

tributaries (Golz, 1992).

FIGURE 18.19 Grain feeding below Iffezheim barrage on the Rhine River near Karlsruhe,

Germany (after Kuhl, 1992).

18.6 FLUSHING FLOWS FOR COARSE SEDIMENT

MANAGEMENT

18.6.1 Importance of Gravel Flushing

Salmon and related species use gravel beds for spawning. The d

50

size for salmonid

spawning gravels is usually between 14.5 and 35 mm, but may include beds with d

50

values in the range of 5.4 to 78 mm (Kondolf and Wolman, 1993). Permeable gravels are

ENVIRONMENTAL AND REGULATORY ISSUES 18.32

essential not only for the spawning success of a number of fish species, but also as habitat

for a variety of crustaceans and insects which sustain stream diversity and productivity.

Fish explore the pool and riffle sequence to locate a site suitable for spawning,

excavate a pit, deposit eggs, and, in some species, backfill with permeable gravel. After

an incubation period of 1 or 2 months, the eggs hatch and the alevins (hatchlings still

attached to their yolk sac) spend another 1 or 2 months in the intergravel environment until

the yolk sac is fully absorbed before emerging as fry. The accumulation of fine sediment

in the gravel diminishes the flow of oxygenated water and reduces the rate of removal of

metabolic wastes produced by the eggs, and dramatically reduces survival of both eggs

and alevin. Coarser sediment such as sand which fills the interstices near the surface of the

bed can trap fry within the gravel matrix, preventing their migration into open water, and

can also fill the interstices used by juvenile fish to escape from predators.

The depth of infiltration into a gravel bed by fines depends on the sizes of the fines

relative to the grains composing the bed matrix. Fine sediment is carried deep into the

bed and accumulates by plain sedimentation within the void spaces. Larger grains may

penetrate only the armor layer, creating a seal by particle bridging within the upper layer

of the subarmor. Observations in tilting flumes indicate that sedimentation within gravel

beds occurs first in the pools and the tail of bars, gradually moving upstream to the head

of the bars. The fine sediments that accumulate in gravels may be removed by large

flows which mobilize the bed and wash out the fines. This cleansing process begins at

the head of gravel bars and moves downstream, in reverse order to the clogging process

(Diplas and Parker, I985).

Gravels are maintained free of fines by high-discharge flushing flows which occur

during flood season and mobilize the bed. These large flows are also important for

maintaining the overall channel capacity and preventing the encroachment of riparian

vegetation into the active channel, which can further reduce the amount of gravel

available for spawning. Dam construction reduces or eliminates the flood flows needed to

flush finer sediment from gravel beds and maintain channel morphology, and also

eliminates the supply of gravels from upstream. These negative impacts are only partially

offset by fine sediment trapping within the reservoir, which will reduce the rate of

gravel clogging. However, in the absence of flushing flows, even low concentrations of

fine sediment will eventually clog the bed. Diminished peak flows below a dam can also

allow sediment to accumulate in pools used for rearing of fish, and will change a

complex braided stream into a single narrow channel with loss of habitat.

Flushing flows to maintain spawning gravels below dams should: (1) mobilize

gravels to flush out fines, (2) be large enough to maintain channel morphology and prevent

vegetative encroachment, and (3) prevent significant downstream transport of gravel

which would deplete spawning beds. These objectives are not complementary. Large

discharges which flush gravels and maintain the channel also transport gravels

downstream, exacerbating the problem of gravel loss and bed coarsening.

Benthic invertebrates, mainly aquatic insects having a lifespan of about 1 year, are

the major food source for anadromous fish. Because these invertebrates cannot move

from one location to another when the water level drops, the lowest flows of the year

delimit the areas where these organisms are most numerous. Continuously submerged

gravel riffles contribute the most food to fish production (Nelson et al., 1987). The lack

of flushing flow can allow encroachment by vegetation, narrowing and deepening of the

channel, affecting not only the availability of spawning gravels, but also reducing food-

producing areas and related habitat. Hydroperiod modification which desiccates the

streambed, as well as reservoir flushing that smothers this habitat, can have disastrous

consequences on benthic fauna and all species that depend on them for food.

ENVIRONMENTAL AND REGULATORY ISSUES 18.33

18.6.2 Factors Affecting Habitat Rehabilitation

Dam construction and other activities impacting rivers have severely affected river biota,

and considerable attention has focused on the management of coarse sediments below

dams to rehabilitate habitat. Many factors have contributed to the continuing decline of

salmon and other ecological changes affecting regulated rivers. Ligon et al. (1995) state

that, despite possibly 10,000 to 15,000 research articles on salmonid biology and ecology,

there is little consensus on the relative importance of dams, commercial harvest,

hatchery-reduced genetic fitness, oceanic conditions, predation, habitat degradation due

to timber harvest, stream degradation by cattle, and other factors which affect fish

populations and survival. Because conditions will vary from one river to another, it is

dangerous to make generalized statements or use a generic approach to habitat

restoration. The conditions limiting populations of salmon or any other species of

concern in one river may be quite distinct from the limiting conditions in another river.

Without a clear understanding of the role of dams and other factors influencing the

decline of any aquatic species or habitat, including a sound understanding of the

geomorphic and sediment transport conditions in the target stream reach, there is

considerable potential for rehabilitation to be misdirected. For example, Kondolf et

al. (1996) reviewed the implementation of the Four Pumps Agreement, passed in

response to the near extinction of salmon in California's Sacramento-San Joaquin

River system. Of the $33 million allocated between 1986 and 1995, 45 percent was

directed to increase populations of striped bass, an introduced species that preys on

young salmon. Another $5.6 million was allocated to hatcheries, apparently in

conflict with the Agreement's guideline that priority funding be given to natural

production, since hatchery fish are known to have a deleterious effect on natural runs

through competition and genetic introgression. Another $3.4 million was allocated to

spawning habitat enhancement projects, although studies showed that spawning

habitat was not a critical limiting factor in this system. Projects to reconstruct

spawning riffles were planned and designed without full understanding of the

geomorphic and ecological effects of upstream dams that modified flow and

eliminated gravel supply, and of instream gravel mining pits that trap bed material

and induce channel incision. Instream mining pits also provide habitat for largemouth

and smallmouth bass, principal predators of juvenile salmon, A survey of three

reconstructed riffles showed that the artificially placed gravels had washed away

within 1 to 4 years, and in some places the post-project bed was even lower than it

was before gravel placement.

18.6.3 Planning Flushing Flows

The periodic release of large flows to flush fine sediment from gravel beds is necessary to

maintain spawning beds. Reiser et al. (1988) outlined a four-step procedure for analyzing

flushing flows:

1. Define purpose and objectives. Prior to undertaking flushing, it is essential to

clearly establish the target sediment grain size and the flushing objectives (e.g., cleaning

of surface sediment, deep cleansing of gravels, maintenance of channel

morphology).

2. Timing. Flushing flows should be scheduled considering factors such as the life

history of important species in the river, the natural flow variation prior to

impoundment, and water availability. Properly timed flushing flows can cleanse

gravels in preparation for spawning, but a later release may wash out eggs and fry.

Recreational benefits (rafting, kayaking) and seasonal variation in water cost (lost

power generation benefits) may also be important. Flushing flows timed to

ENVIRONMENTAL AND REGULATORY ISSUES 18.34

coincide with high runoff events in undammed tributaries can minimize the

release required from the dam.

3. Flushing discharge. In undertaking gravel flushing, the objective is to mobilize

the sediment bed and remove fines, while minimizing the net downstream

transport of gravel, and the optimal flushing domain may be very narrow. However,

there is no standardized method for computing flushing flows. Reiser et al. (1988)

enumerated 16 different published analytical and field techniques used to estimate

flushing flow, and reported that different techniques can give flushing flows

differing by as much as 800 percent. Because stream hydraulic characteristics are

irregular, at a given discharge a portion of the gravel beds in the stream will be

flushed. In streams where spawning gravels occur in patches, hidden from the

areas of maximum current flow by boulders or stream morphology, mean

hydraulic and bed shear conditions along the stream give little indication of

conditions in the spawning gravel. This makes it difficut to establish more than

approximate values for flushing flows using analytical technicques. In such cases,

the effects of different flushing discharges should be monitored to determine the

optimal flow rate. An example of this procedure is described by Reiser et al.

(1989).

4. Flushing effectiveness. The effectiveness of flushing flows should be evaluated by

field inspection and quantification. These observations will be the basis for recom-

mending adjustments in the discharge and duration of subsequent flushing flows.

Several methods may be used to monitor flushing effectiveness. The initiation of

motion may be monitored by gravel tracers, stones colored with bright waterproof

paint which are placed on a gravel bed and monitored for movement. Tracer stones

found at a downstream point, or not found at all after a given flow, have been

mobilized. This technique is useful for determining the discharge corresponding to

the initiation of motion in different areas of the stream. Scour depth can be

determined using scour chains in different locations (Fig. 8.20a), and net changes in

bed configuration can be quantified from before and after cross-section surveys.

The change in size distribution of sediment within the gravel bed can be

determined by bulk sampling (Fig. 18.20b) or the freeze core technique. Bed

surface conditions can be documented by photography.

18.6.4 Analytical Flushing Flow Computations for Gravel Cleansing

Flushing discharge can be estimated by the criterion of incipient sediment motion based

on Shields parameter. Gessler (1971) determined that a given particle will have a 5

percent probability of movement for a Shields parameter value of 0.024, and a 50

percent probability for a parameter value of 0.047. From flume studies of graded

sands and gravels (0.25 to 64 mm), Wilcock and McArdell (1993) found that

complete mobilization of a size fraction occurs at roughly twice the shear stress

necessary for incipient motion of that fraction. Thus, as a first estimate, bed shear

stress values between 1 and 2 times the critical bed shear stress τ

CR

might be suitable

for flushing without causing excessive downstream transport of gravel. In some

cases it may be desired to remove finer sediments from the surface of a coarse armor

layer, without mobilizing the armor layer itself. The bed shear τ to achieve superficial

flushing may be estimated by:

surfaceflush

2

/

3

CR

where τ

CR

= critical bed shear stress for the armor layer (Milhous and Bradley, 1986).

Average bed shear stress values may be related to discharge by using stream cross

ENVIRONMENTAL AND REGULATORY ISSUES 18.35

FIGURE 18.20 Tools useful for determining flushing impacts. (a) Use of scour chain to determine

depth of bed mobilization during a flushing event. (b) McNeil type gravel sampler for bul

k

sampling. The stainless steel sampler is pushed into the gravel to the weld line and gravel is

scooped by hand from the core into the outer ring.

secti

ons and hand computation by the Manning equation and the average stream

slope along the reach, or by using a hydraulic model. The initiation of sediment motion

is discussed in Chap. 9. In the evaluation of flushing flow in the North Fork Feather

River, several transport equations were used to select the recommended flushing

flow discharge and duration, as described in Sec. 22.9. For more complex cases,

sediment transport modeling would be recommended.

Computations using the Shields parameter assume conditions of loose, noncohesive

sediment. Sand-embedded gravels, especially with a cemented organic crust or

containing clay, may require mechanical loosening by heavy equipment for flushing to

be successful.

18.6.5 Gravel Flushing in Trinity River, California

An example of the complexities of gravel management in Northern California's Trinity

River below Lewiston Dam is presented by Nelson et al. (1987). Chinook salmon and

steelhead trout are the species of critical concern.

Eighty percent of the average runoff from the upper watershed has been

diverted from the basin for hydropower and irrigation, and the annual flood peak has

decreased from 525 to 73 m

3

/s. Extensive clearcutting and logging road construction in

the watershed disturbed the erodible soils, increasing the delivery of coarse sand to the

river. The reduced flows are unable to transport this sediment, and sands have filled

pools, buried cobble substrate, and clogged spawning gravels, thereby degrading the

habitat for anadromous salmonids which were formerly abundant in this reach.

Reduced flows also allowed riparian vegetation to encroach into formerly active

channel areas, producing a deeper and narrow channel which reduced the area of

shallow riffles important for food production. Sediment-related stream rehabilitation

ENVIRONMENTAL AND REGULATORY ISSUES 18.36

measures considered for this stream include watershed rehabilitation to reduce

sediment inflow, construction of debris darns to trap sand, mechanical loosening of

compacted sediments, artificial replenishment of depleted gravels, removal of

encroaching riparian vegetation, and flushing. Because of the large volume of

flushing water required, and the high opportunity cost of lost water due to foregone

power production and irrigation, flushing was considered a high-cost option.

Using tracer gravel particles, Kondolf and Matthews (1993) found that a 5-day

flushing flow release of 170 m

3

/s would mobilize most of the gravels, but did not

significantly alter the sand:gravel ratio because the duration was not sufficient to flush

sands out of the river system. Flushing flows exceeding 240 m

3

/s are not considered

feasible because they would accelerate gravel loss below the dam and would also

exceed the 100-year flood level computed for post-dam conditions. The

sustained releases that would be required to flush the sand out of this system are

extremely costly because of the value of the water. Dredging of sand accumulation

from pools was recommended as an alternative.

18.7 CLOSURE

The environmental impacts of dams and their disruption of riverine sediment

transport processes vary tremendously from one site to another, and the nature of the

problem and mitigation options may be extremely complex. The regulatory

environment is similarly variable, with water quality and sediment management

issues potentially falling within the purview of multiple regulatory jurisdictions

(federal, state, and local), and multiple users (water supply, recreation, fisheries,

power production, irrigation, navigation, flood control, and upstream land uses).

In some areas of the world, darn building is still being undertaken on a large

scale, but in areas such as the United States, where impoundment capacity equals

about 60 percent of annual runoff, the critical issue is no longer dam building but

improved management of the existing infrastructure (Collier et al., 1995).

Sediment management is not only essential for the sustained utilization of reservoir

storage, but also is equally important for the maintenance of acceptable

environmental conditions in rivers below dams.

CHAPTER 19

CASE STUDY:

CACHÍ HYDROPOWER RESERVOIR,

COSTA RICA

19.1 PROJECT OVERVIEW

19.1.1 Project Description

The 54-Mm

3

Cachí hydropower reservoir was constructed on the Reventazón River in

Costa Rica in 1966 (Fig. 19.1). It was first emptied for flushing in 1973, and over the

next 18 years it was flushed 14 times. Flushing maintained the power intake free of

sediment and reduced the reservoir trap efficiency from 82 to 27 percent. Flushing

operations at this reservoir have been both well-documented and very successful in

preserving storage capacity. This case study description is based on investigations

conducted jointly by the department of Physical Geography, Uppsala, Sweden, and the

Instituto Costarricence de Electricidad (ICE), which owns and operates the project, and

on the first author's observation of the 1990 flushing event and discussions with Alexis

Rodríguez, Ake Sundborg, and Margaret Jansson.

Cachí Dam is a single-purpose hydroelectric facility. The dam is a 76 m tall and 184

m long concrete arch structure with two radial crest gates and a 3.8-m-diameter power

tunnel running 6.2 km to the power house. Three Francis-type impulse turbines are

installed with 100.8 MW of capacity and 246 m of usable head. The dam has a single

bottom outlet with two bottom gates. There is a vertical sluice at the upstream end and

a radial gate at the downstream end of the outlet tunnel through the dam. Guides for an

emergency sluice gate are provided at the upstream entrance to the bottom outlet. The

bottom outlet was placed near the thalweg of the original river channel and immediately

adjacent to the intake screen, a location that facilitates flushing of sediment from in

front of the intake. Pertinent elevations are:

Full reservoir level 990 m

Spillway crest 980 m

Minimum generating level 960 m

Power intake sill level 936 m

Sill of bottom outlet 921.5 m

This is the first major hydroelectric project on the Reventazón River. Several others

downstream of the Cachí site are in the planning stage.

CACHÍ HYDROPOWER RESERVOIR, COSTA RICA 19.2

FIGURE 19.1 Location map of Cachí reservoir on Rio Reventazón, Costa Rica, showing the

tributary streams and gaging stations (Ramírez et al., 1992).

The reservoir had an original capacity of 54 Mm

3

in 1966 and a surface area of 324

ha. It is approximately 6 km long with maximum and minimum widths of 1.5 and 0.13

km, respectively. A narrow section about 4 km upstream from the dam divides the

pool into "upper" and "lower" basins. The floor of the lower basin of the impoundment

consists of a series of relatively flat river terraces, onto which fine sediment is

depositing, with a deep river channel maintained by flushing. In contrast, the upper

basin is filling with sand and coarser material which is not removed by flushing. During

drawdown for flushing the river exhibits a braided pattern across these coarse delta

deposits in the upper basin. The bathymetric map (Fig. 19.2) illustrates these features.

Figure 19.3 is a photograph of the reservoir looking upstream from the dam during the

1990 flushing event, showing the deep incised channel and natural river terraces on either