Morris & Fan. Reservoir Sedimentation Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.21

5. Are inflexible

6. Create political antagonism within the local community or the government

12.6 EROSION CONTROL ON MECHANIZED FARMS

Soil conservation was initiated in the United States in the 1930s, when dust bowl

conditions in the midwest were merely symptomatic of the lack of conservation that

characterized agriculture nationwide at the time. Soil conservation technology was in

its infancy, and farmers generally lacked knowledge of erosion control techniques. Land

abuses were widespread and readily apparent, not different from many less-developed

areas of the world today. Farms were literally being washed away by rain and blown

away by wind.

Present conditions are remarkably different in the United States, as in most other

mechanized agricultural areas in the world, where the most obvious soil erosion problems

have been controlled. On the basis of conditions in the mid-1980s, Colacicco et al. (1989)

estimated that two-thirds of U.S. cropland will suffer no yield loss over the next 100

years, since most land is eroding at less than the tolerable rate and suffers no productivity

loss. Despite erosion, productivity losses on the remaining lands can be largely offset by

increased fertilization.

Successful implementation of erosion control techniques across the diverse U.S.

landscapes is the product of many efforts: erosion control research in experiment stations,

sustained implementation efforts nationwide for some 60 years by the Soil

Conservation Service (now renamed Natural Resources Conservation Service),

increased public awareness and demand for enhanced water quality, an increasingly

stringent regulatory environment, and of great importance, the elimination of

cultivation on steeply sloping soils. Nevertheless, erosion, runoff quality, and reduced

infiltration rates are problems that still require more work in many areas. Two recently

formed watershed groups in Illinois were profiled by CTIC (1996), and are representative of

the approaches and concerns of watershed management in agricultural areas of the United

States. Both watershed groups are composed of area landowners, interested citizens, and

locally active personnel from a variety of government agencies, and were organized to

address problems of local significance.

In the watershed tributary to Lake Springfield, which had been dredged (Sec.

16.5.1), the two key issues were continued sedimentation and contamination of the

drinking water reservoir with a herbicide widely used by local farmers. Floods in 1994

deposited a volume of sediment equal to about 10 percent of the volume dredged, and

represented about $1 million in future dredging costs. Remediation includes best

management practices such as no-till, erosion control structures, filter strips, streambank

vegetation, and improved herbicide application practices.

Flooding during 1993 was the key problem that initiated watershed protection

activities in the Embarras River watershed. A nonprofit river management association

was formed to provide local landowners with the organizational structure needed to

implement a comprehensive resource plan developed for a 12-county watershed.

Although flooding catalyzed action, the list of concerns grew to include: log jams, water

quality, erosion, drainage, wildlife, better communication and accountability, loss of the

natural character of the river, private property rights, instream sedimentation, recreation,

water supply, land use change, wetlands, small bridges and culverts, and funding sources.

Implementation of conservation tillage on 75 percent of the 450,000 ha of farmland in the

watershed is expected to reduce peak flood discharge by 10 percent, and normally dry

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.22

flood control dams will provide an additional 15 percent reduction in peak discharge.

Together these measures are expected to reduce soil loss by about 1.5 million tons a

year.

Farmers are reluctant to implement soil conservation measures unless there is an

economic incentive to do so in terms of reduced production costs, increased yield, or

subsidies. Conservation tillage is often implemented as a cost-saving measure rather

than for erosion prevention. Sloping soils which cannot be tilled with tolerable rates of

erosion are recommended for permanent pasture or woodland, in accordance with the land

capability classification system, but farmers may be unwilling to take land out of crop

production. Because the on-farm cost of erosion is relatively low in the United States,

and off-farm costs may be more than double the on-farm costs, erosion prevention has

relied heavily on subsidies paid to farmers (Napier, 1990). Under the Conservation

Reserve Program initiated in 1985, farmers were paid an annual rent plus half the cost

of establishing a conserving land cover, in exchange for the retirement of highly

erodible or other environmentally sensitive land from crop production under 10-year

contracts. By 1993 some 36.5 million acres, or about 8 percent of U.S. farmland, was

included in the program at an average cost of $122/ha/yr (Table 12.2). The program was

TABLE 12.2 Conservation Reserve Program in the United States

Parameter Value

Contracts 377,000

Enrollment, ha (acres) 14.8 × 10

6

(36.5 × 10

6

)

Total erosion reduction t/yr (tons/yr) 635 × 10

6

(700 × 10

6

)

Total rental cost, $/yr 1.8 × 10

9

Average annual rental cost, $/ha ($/acre) 122 (50)

Area planted in trees, %

6

Source: Osborn (1993).

estimated to have reduced erosion by 635 million tons/yr, an average of 43 tons/ha,

representing a 22 percent reduction in the total erosion from cropland nationwide. A

limitation of this and similar subsidy-based programs is that when the subsidies expire,

the land may be returned to crop production (Osborn, 1993). This cost of avoided

erosion is about $2.83/ton, which is close to the cost of dredging sediment from reservoirs.

This makes it a very costly approach for curing reservoir sedimentation, especially if the

sediment delivery ratio is low.

Given the cost of subsidies for conservation set-asides, coupled with budgetary

limitations, Ervin (1993) postulated that erosion control in the agricultural sector may be

expected to gradually abandon subsidies and move increasingly into the regulatory

arena, as the demand for environmental quality increases and political power shifts

away from agricultural groups.

12.7 EROSION CONTROL ON SUBSISTENCE FARMS

Issues related to the implementation of soil and water conservation on subsistence farms

are discussed in Moldenhauer and Hudson (1988), Hudson and Cheatle (1993), and

Napier et al. (1994).

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.23

5.1.1. 12.7.1 Erosion Control Strategy

Hudson (1988) has pointed out that one of the keys to erosion control in the United

States is the system of land capability classification, which identifies slopes steeper than

12 percent as unsuitable for open cultivation. Adherence to this criterion is possible in the

United States, with its abundance of fertile lands on low slopes and dispersed pattern of

land ownership. However, in many tropical areas this system is entirely irrelevant

because the area of flat soils is small, the best lands are concentrated into large

landholdings, and the expanding population of the poor is forced onto soils of ever-

increasing slopes for survival.

When an erosion problem is identified in a watershed, there is a tendency to develop

and implement a "soil conservation" program. However, this top-down approach has

largely been ineffective against erosion, as evidenced by the failure of projects of this

type worldwide. Farmers control the use of the land they till, and are rarely willing to

implement costly soil conservation measures, or change their production practices,

unless there are tangible benefits to themselves and their families. The application of

structural erosion-control measures on subsistence farmers has often been unsuccessful;

the measures have not been maintained, and in some cases they were even dismantled

by the people they were supposed to benefit. Shaxson (1988) cites an example of well-

meaning conservation programs in some African countries requiring the construction of

contour banks on cultivated land. This provoked severe resentment of government

officials, especially when farmers who did not perform the required work were fined or

jailed. People were especially embittered when they saw that even where the banks were

installed, erosion did not end. In Nicaragua, Obando and Montalvan (1994) reported that

machinery was used to construct structural conservation measures on farms in the

watershed south of Lake Xolotlan to provide flood protection for the city of Managua.

These measures, which were constructed at no cost to the farmers, generally interfered

with common cultivation practices in the area. Many of the structures were either

abandoned or undermined by the farmers, who returned to their traditional practices.

This and other similar experiences noted in the literature underscore the importance of the

socioeconomic aspect of erosion control and involvement of the local people. An

important challenge is to develop conservation practices that not only reduce erosion but

also increase land productivity.

Successful erosion control projects will focus on practices that improve the farmer's

condition while simultaneously conserving soil and water. This concept has been

termed conservation farming or land husbandry by Hudson (1988). Conservation

measures are most likely to be profitable, and thus implemented, when they are cheap and

simple, or when they allow improved agronomic practices to be implemented. Even

when the principal impact of soil loss is offsite (e.g., reservoirs), the farm-level

approach is still appropriate because conservation measures must be implemented and

sustained by farmers themselves.

12.7.2 Terracing

The retardance of runoff and trapping of sediment is a key management practice on

sloping soils. Terraces (or earthen bunds) have been widely used and represent the basis

of sustained agricultural production in many areas of the world. Terraces may be

constructed of stone, or of earth with permanent vegetative cover to protect and stabilize the

terrace slope. Terraces are costly (labor-intensive) to construct and maintain, and will

not be sustained by the farmer unless there are tangible benefits. However, once the

benefits are realized, farmers will construct and maintain terrace systems. In

Ecuador (Nimlos and Savage, 1991), poor farmers constructed terraces because it was

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.24

part of an agronomic package that generated dramatic yield increases (more than double

for some crops), and the level soil was also easier to farm. In some areas of Kenya

terraces are required to trap enough moisture to prevent crop failure in dry years

(Wenner, 1988).

The benefits of terracing are highly site-specific. In drier climates terraces may be

required to trap enough water to undertake crop production, but on heavy clay soils,

terraces can create waterlogging and decrease crop production. Contour-grassed hedges

of vetiver may function much more satisfactorily than traditional structural terraces in

many situations.

Research and experiment stations have tended to favor terracing and similar soil

conservation methods which have high levels of technical efficiency, rather than methods

having high levels of cost-effectiveness to the farmer. Although terracing is a highly

effective method for reducing erosion, it is also costly to implement and maintain, and

because terracing may take some land out of production it may actually reduce the short-

term yield (Lutz et al., 1994). Terracing may also disturb the soil in a manner that brings

less productive soil to the surface. Depending on the setting, these costs can make

terrace construction economically unattractive to farmers. Structural measures have been

successfully employed in a number of regions, but are not the answer to all sloping soil

erosion problems. Methods such as construction of contour ditches and use of grass

strips and organic fertilizers are conservation measures that are less costly to implement

than terraces and may be considered more beneficial by farmers.

12.7.3 Agronomic Strategies to Reduce Erosion

Good agronomic practices produce a soil having a high infiltration capacity, achieved by

maintaining high levels of organic matter and soil cover in the form of either vegetation

or mulch. Sloping soils are modified to create terraces which retard runoff, thereby

enhancing infiltration and providing more water to sustain plant growth, and also

trapping soils and nutrients which would otherwise be lost with the runoff. Level soils

are also easier to cultivate than steep slopes. Retarding runoff and providing proper

drainage channels also helps preserve farm roads. All of these practices both benefit the

farmer and reduce erosion.

Agronomic conservation strategies used on subsistence farms focus on techniques

such as tillage reduction and intercropping to maintain a continuous cover of vegetation

or mulch, return organic material to the soil, and maximize water infiltration. Nitrogen-

fixing legumes are planted to improve soil fertility. Compost prepared from crop residue

and animal manure is spread back on the field as fertilizer. Crops are planted on the

contour, and strip cropping is used. Grass buffer zones which may be used for cut-and-carry

forage are set on the contour to trap sediment from fields, and stiff grass hedges may be

used to build natural terraces. Multiple cropping and multilayer cropping systems tend

to produce a more ecologically balanced environment, reducing both soil erosion and pest

problems. These systems can also reduce risk to the farmer, as when two crops with

somewhat differing tolerance to extreme wet or dry conditions, such as maize and

sorghum, are planted together in areas subject to drought to ensure against total crop

failure. The two following examples illustrate the application of these principles.

12.7.4 The World Neighbors Program in Honduras

World Neighbors (Vecinos Mundiales) is a nongovernmental organization (NGO) that

works in poor rural communities and extends knowledge about soil conservation and

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.25

other subjects. The organization's experience with soil conservation projects in Honduras

has been summarized by López-Vargas and Pío-Carney (1994).

In the initial stage of work with communities, farmers often do not believe in soil

conservation. Many claimed that breaking up the soil was foolishness, that constructing

ditches on the contour was for burying people, that collecting dung for composting was

a dirty job, and that because nothing grows on eroded lands it is better to move

elsewhere when the land becomes exhausted. The farmers may also not be familiar with

new or alternative crops.

Technical training must initially make individuals aware that they are the only

persons responsible for resolving their own problems and, above all, that they have the

capacity and intelligence to do so with a little effort. For long-term effectiveness farmers

must come to understand contributions of air, sunlight, water, nutrients, and soil

organisms to the formation of the crop, as well as the role that the forest plays in the

entire system and in human life. They must realize the responsibility they have to be

good administrators of nature and the potential they have to make nature useful and to

provide a better life, not only in the present but also in the future and for future

generations.

Practical and simple techniques are recommended for conserving soil structure,

moisture-retention capacity, and fertility. Diversion ditches are designed to reduce the

speed of flowing water, and in dry areas level ditches are used to capture runoff and

encourage infiltration. Vegetative barriers filter soil from water flowing downslope, and

the gradual accumulation of soil helps form natural bench terraces over years.

Vegetative barriers can also produce forage for livestock and vegetative material for

organic fertilizer. On rocky soils, rock barriers are constructed on the contour. Where

possible, minimum tillage techniques are used since they are less labor-intensive than

traditional tillage and also reduce erosion by minimizing the area of soil disturbance.

Organic fertilizers are prepared by composting vegetable matter and fresh dung from

livestock, and after composting the fertilizer is applied at the rate of 2 to 4 kg/m

2

. Dung

is not applied directly to crops without composting because it can attract insect pests.

Legumes such as velvet bean are planted as green fertilizers, since they not only fix

nitrogen but also produce seeds that can be processed to produce flour and tortillas, and

vegetable matter for incorporation into organic fertilizer. Simple conservation

structures such as diversion ditches, maximum use of organic material, narrow furrows

with minimal soil disturbance, and the minimal use of chemical fertilizer are the key

elements to the program.

The Vecinos Mundiales project workers start in each community on a small scale by

recommending a few simple techniques and applying them on small plots using native

varieties and tools. They build on existing local knowledge and techniques, and seek to

achieve gradual change. The objective is to slowly but surely alter production

techniques, incorporating the best traditional techniques with new ones as appropriate.

More people will become interested and the program will grow as the initial results are

proven in the field. Farmers are encouraged to share with others, and local extensionists

are recruited from those farmers who effectively practice what they preach. Total

acceptance is not expected, but participation levels of 60 to 80 percent are customary.

12.7.5 Implementation in Ecuador

Nimlos and Savage (1991) described the USAID-funded Sustainable Land Use

Management Project in Ecuador, which seeks to introduce sustainable soil conservation

practices and a conservation ethic to indigenous Quechua farmers cultivating steeply

sloping lands. The fertile level lands at lower elevations are owned by wealthy

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.26

landowners and are used mostly for grazing; poor subsistence farmers have access only

to marginal lands. The project area is located at elevations between 2300 and 4500 m,

slopes of 50 to 70 percent are common, and 80 percent of the parcels are less than 1 ha in

size. The men often travel to the city to seek work, leaving women to work the fields.

The program used 60 extensionists with 2 to 6 years of technical education, who

trained about 3500 farmers. About 9000 ha received conservation treatment, and the area

under improved cropping (strip-cropping, intercropping, crop rotation, contour cultivation,

and green manuring) approximately doubled every year. Construction of conservation

structures including hillside ditches, bench terraces, and earthen reservoirs increased by

about 70 percent per year. The program also provided assistance in the safe management of

pesticides, use of fertilizer, agroforestry, and native forest management. Crop production

increased dramatically: garlic by 92 percent, peas 421 percent, barley 216 percent,

onions 80 percent, beans 47 percent, potatoes 260 percent, melloco (a native fruit) 475

percent. The implementation rate for conservation treatments was highest in areas where

the increase in crop production was the most dramatic. The program was a success and

soil-conserving practices were expanded because the needs of poor farmers were

addressed and conservation practices increased yields.

Terracing was used to trap soil, and the combination of terracing and green manure

enabled farmers to grow crops in areas that had previously been unusable because of

severe erosion. Terraced lands are much easier to irrigate and cultivate, trap more

moisture, and produce much higher yields. In the project area, unterraced land was valued

at $160/ha, but its value increased to $2200/ha when terraced.

12.8 EROSION CONTROL AND FORESTRY

PRACTICES

12.8.1 Definitions

A silvicultural system refers to the methods in which trees are harvested and the stand is

regenerated. They include clear-cutting and variations thereof which produce even-aged

stands of timber, and single-tree or group selective-cutting techniques which maintains an

uneven-age stand structure. A logging system refers to the method used to fell trees, cut

them into logs, and transport the logs from the stump to a temporary storage area (the log

landing), from whence they are transported to the mill. The yarding system refers to the

method of transporting logs from the stump to the log landing and is the most critical

aspect of the logging system from the standpoint of erosion. Logs can be transported to the

landing by dragging or skidding with a tractor, a ground-level cable and winch, or

animals such as oxen and elephants. There are several types of skyline yarding systems

which either partially or wholly suspend logs in the air during transport, greatly

reducing soil disturbance. If a helicopter is used to remove logs, the method is termed

aerial yarding.

In some areas of the United States it is necessary to assess the cumulative impact of

timber harvest and other activities on water quality. The cumulative effect is the total

environmental impact resulting from the incremental impact of a proposed action, when

added to all other past, present, and reasonably foreseeable future actions, regardless of

who undertakes those actions. The idea behind a cumulative impact assessment is that

sensitive downstream uses, such as fishery habitat, can tolerate only a limited degradation

in stream quality. Therefore, all contributors to water quality degradation should be

considered when determining whether or not additional degradation is acceptable

(Cobourn, 1989; Sidle and Hornbeck, 1991).

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.27

Forest harvest activities, including erosion control measures, should be planned in

advance by preparing a timber harvest plan. A timber-harvest plan includes maps,

sketches, or photographs of the area to be logged. It specifies the logging methods to be

used, landing locations, the stream areas to be protected with buffer strips, and the width

of the buffers. It gives specifications for the construction, use, and maintenance of a

well-designed transport system, and it will also specify the methods to be used to repair

and stabilize logged areas, log landings, and roads upon completion of the harvest

operation. As part of timber harvest planning, areas of high erosion potential should be

identified and road construction avoided in these areas. Some flexibility should be

retained to allow adjustment to conditions encountered in the field.

12.8.2 General Strategies for Erosion Control

Natural forest represents the best type of vegetative cover available: forest soil is highly

permeable, and a layer of litter protects the soil from direct raindrop impact. Because of

the high infiltration rate, only rare and extreme rainfalls are capable of producing surface

flows. On steep slopes, a large percentage or even the majority of the long-term erosion

from forests can originate from slope failures during extreme rainfall events.

Commercial timber harvest disturbs a limited area of the forest floor for a very short

period of time, after which there is a cycle of regeneration and growth which may last

from 20 to 100 years before the next harvest. With timber harvest rotations of 20 years or

longer, and provided that vegetation recovers rapidly, the period of high erosion rates due

to sheet erosion is limited. Most sediment from timber harvest is derived from haul roads

and skid trails. Ill-designed and poorly constructed forest roads concentrate flows, create

gullying, and produce sediment for a period of many years. Consequently, sediment

control methods are oriented to: (1) reducing the amount of land that is disturbed by

roads and skid trails, (2) preservation of riparian stream corridors, (3) proper road design

and construction, and (4) rapid regeneration to protect the soil. General principles of

erosion control have been summarized from Gilmour (1977), Hyson et al. (1982),

Megahan (1983), and Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (1990).

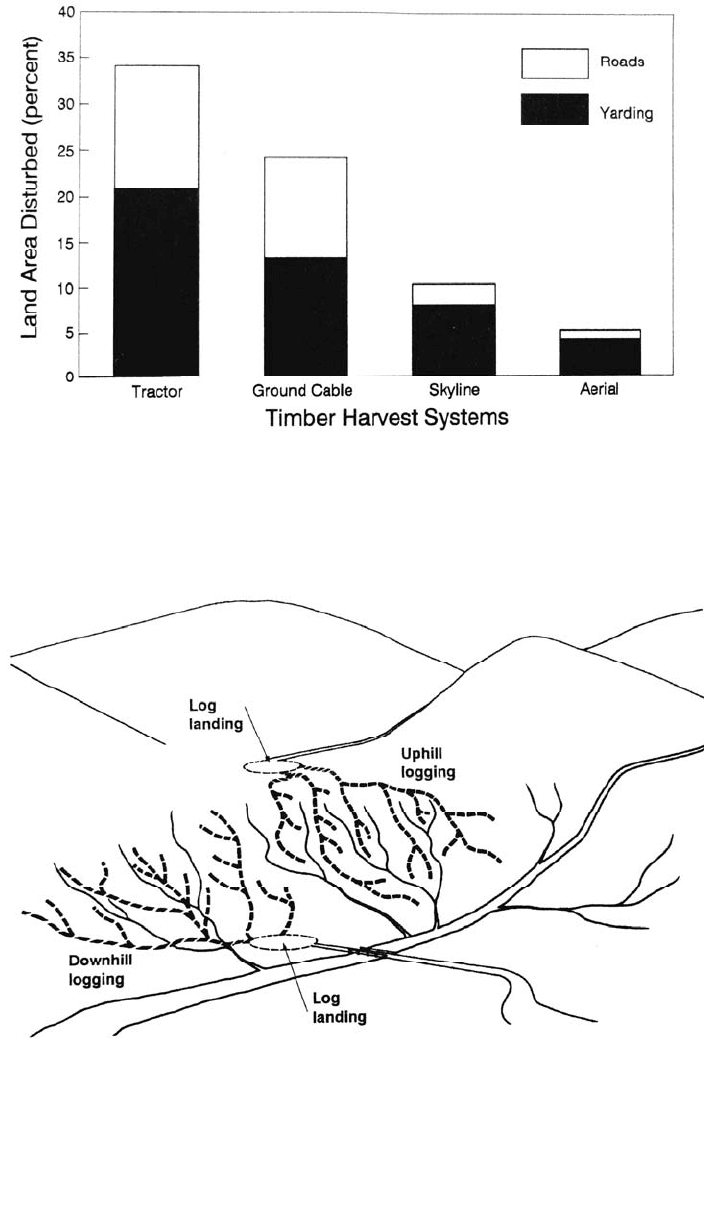

12.8.3 Yarding Methods

Large differences in impacts can be associated with different yarding systems, because of

the large difference in the amount of soil surface disturbed by the various systems (Fig.

12.10). In general, the yarding system that minimizes the area of disturbed soil will

produce the least erosion, other factors being equal. Specific recommendations for

yarding are given below.

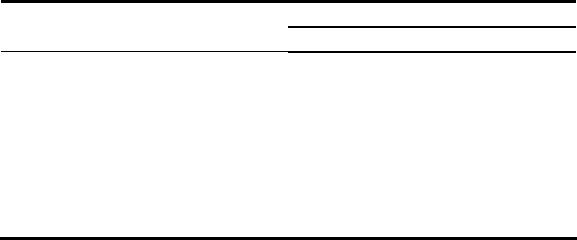

Yard logs uphill rather than downhill, since this produces a pattern of skid trails that

tends to disperse runoff rather than to concentrate it (Fig 12.11).

Avoid stream channels insofar as possible in all phases of the yarding operation.

Never locate skid trails along stream corridors, and drain muddy water in skid trails

away from streams. Use temporary log or metal culverts at stream crossings, and,

when skyline yarding, lift logs across streams rather than dragging them.

Suspend logging on rainy days and periods immediately following rains when soils

are saturated. Operate logging equipment only when soil moisture conditions are such

that excessive soil damage will not occur.

Avoid tractor yarding on soils exceeding 30 percent slope, or 25 percent on soils of

high erosion hazard.

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.28

FIGURE 12.10 Average soil disturbance attributed to roads and yarding for differen

t

logging systems, based on 16 studies in the United States and Canada (

M

egahan,

1981).

FIGURE 12.11 Yarding in the uphill direction creates a pattern of skid trails tha

t

tends to disperse rather than concentrate runoff (redrawn from Gilmour, 1977).

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.29

Minimize logging roads and skid trails on very steep slopes or fragile soils by

using a skyline or aerial yarding system.

Obliterate and stabilize all skid trails by mulching and reseeding immediately upon

completion of logging. If necessary, also construct cross drains on abandoned skid

trails to divert runoff onto the forest floor and prevent gullying.

12.8.4 Log Landings

Log landings are relatively flat areas where logs are temporarily stored before being

transported to the mill.

Locate landings so that skid trails leading to landing areas will minimize impacts on

natural drainage channels.

Landings should be located on areas of gentle slope such as ridge tops or widened

road areas. Locate landing areas on firm ground away from stream channels, and

drain landings into well-vegetated buffer areas.

Landings and other intensive work areas should be kept free of chemicals and fuel,

and should be located away from streams, springs, and lakes, and outside of riparian

areas.

Upon abandonment, ditch and mulch the landing area to prevent erosion. If the

landing will be used repeatedly for thinning operations, plant with herbaceous

material. If it will not be used again for many decades, as in a clear-cut area, plant

trees.

12.8.5 Riparian Buffer Strips

Undisturbed strips of native vegetation which are preserved between streams and areas

disturbed by road construction or logging will reduce the quantity of sediment and

logging slash that enters the stream. Maintaining the environmental integrity of a riparian

buffer zone (also called a streamside management area, SMA) is highly beneficial to

water quality and aquatic habitat, and to terrestrial species as well. The riparian zone

should be maintained in native vegetation to provide bank stability, and to provide shade

that maintains low stream temperatures needed for the survival of some fish species.

The buffer should be of sufficient width to trap sediment and nutrients in the runoff from

adjacent disturbed areas. When trees in the buffer strip are to be harvested, fell trees

away from the stream and remove logs carefully to minimize disturbance. Large and

older trees should be maintained in this zone as a source of woody debris that is an

important component of the stream ecosystem. Slash and other logging residue should

never be deposited in streams or in the riparian buffer zone.

One of the purposes of a riparian buffer strip is to trap sediment that originates in an

upslope area, before it enters a stream. The recommended width of buffer strips will

vary depending on site conditions, but a minimum width of 25 m on each side of the

stream may be used as a guideline (Megahan, 1977). Strips might be narrower in areas

of low slope with careful control in adjacent logging areas, but much wider in heavily

disturbed areas with unstable soils. Buffer widths recommended by various states within

the United States generally vary from about 10 to 60 m on each side of the stream, with

larger widths required on soils having steeper slopes and more erodible soils. The

widths recommended by Maine (Table 12.3) are representative.

REDUCTION OF SEDIMENT YIELD 12.30

TABLE 12.3 Recommended Filter Strip Widths in the State of Maine

Source: AWWA (1995).

Width of strip along slope

12.8.6 Logging Roads

Logging produces a high density of roads, on the order of 2 km of road per square

kilometer of logged area. Roads concentrate runoff and can create long-term problems of

gully erosion if runoff is not handled properly. Important sediment sources related to

roads typically include stream crossings, fill slopes, poorly designed road drainage

structures, and roads close to streams. Roads run across the slope and intercept any

downslope runoff, and contribute additional runoff from the relatively impervious road

surface. This flow can become quickly concentrated along unlined ditches and can cause

gullying along the road; it can also cause gullying when it is diverted downslope.

Practices to reduce erosion from logging roads have been summarized by Megahan

(1977):

Design the transportation system and locate landings to minimize total mileage,

considering both skid trails and haul roads.

Design roads and skid trails to follow natural contours. Avoid the use of

switchbacks in steep terrain by using an alternative road layout. Avoid stacking

roads by using longer-span cable harvest techniques.

Space cross drains to provide adequate drainage and prevent the concentration of

roadside flows into erosive torrents.

To improve slope stability, design cut-and-fill slopes for stable angles less than the

normal angle of repose. If the terrain is too steep for this to be practicable, use

engineered slope stabilization techniques.

Use existing roads wherever practical when they meet adequate erosion control

standards, or can be upgraded to meet those standards, thereby minimizing the amount

of new disturbance and construction.

Orient road crossings at right angles to streams. Cross streams along straight reaches

having stable bank material. Size permanent culverts or bridges to pass large storms

(e.g., 25-year). At temporary crossings, remove metal or log culverts and

reconfigure, mulch, and replant the streambank as soon as operations are

completed.

Characteristics of poor and good road design and maintenance are schematically

compared in Fig. 12.12.

Land slope, % m ft

0 7.6 25

10 13.7 45

20 19.8 65

30 25.9 85

40 32.0 105

50 38.1 125

60 44.2 145

70 50.3 165