Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

BARKIER ISLANDS

45

Offshore Bar Accretion (de Beaumont, 1845)

barrier

island

sea level

mainland

offshore

shoal

Spit Accretion and Breaching (Gilbert, 1885)

mainland

ocean

storm breach

{tidal channel)

barrier/

island

Mainland Detachment (Hoyt, 1967)

mainland lagoon barrier

submergence

mainland

beach ridge

(time 1}

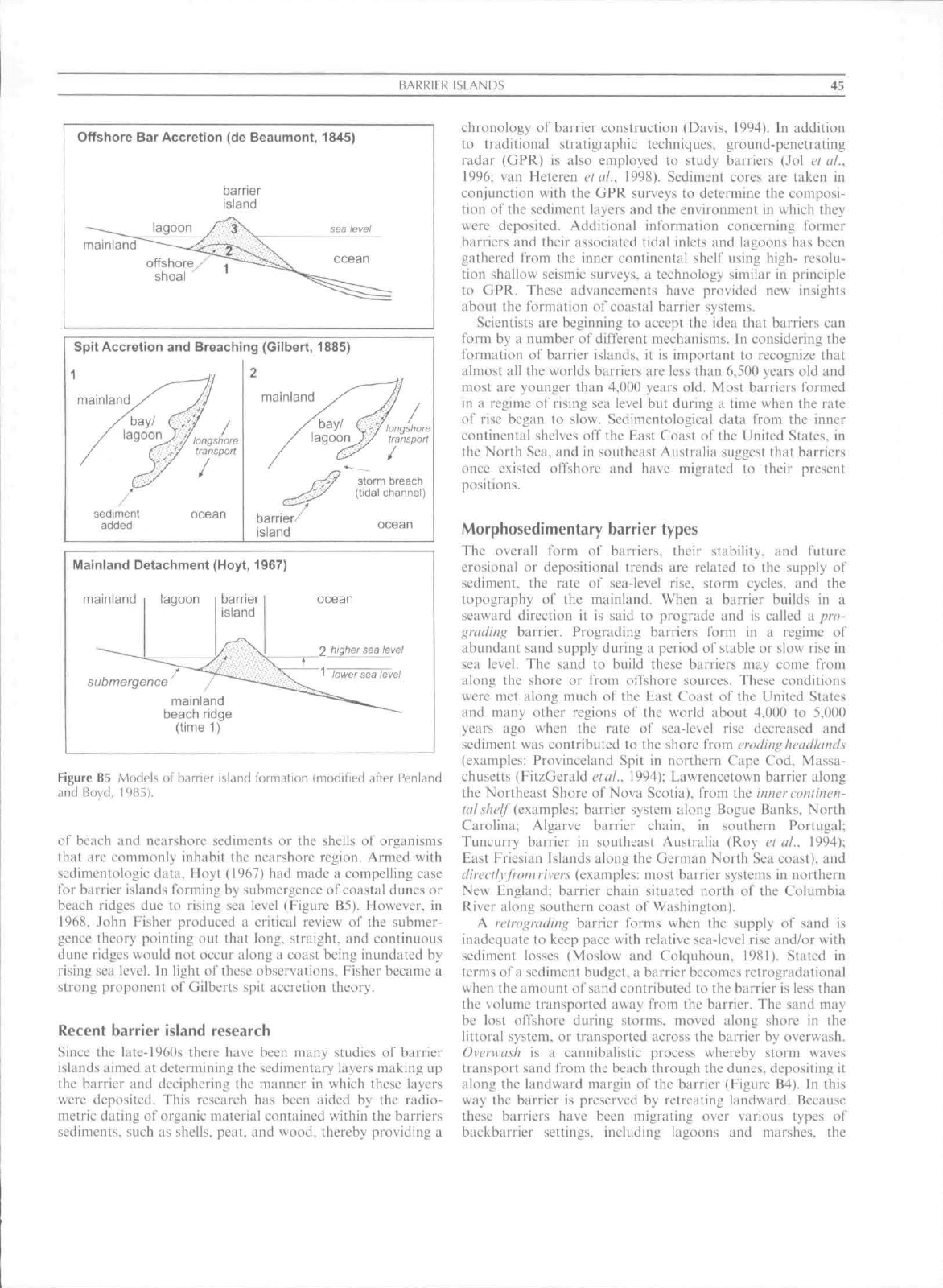

Figure B5 Models of barrier island torrriiHion (modified al'fer Peniand

and Boyd, 1985),

of beach and ncurshorc sediments or the shells of organisms

thiit are commonly inhabit the nearshore region. Armed with

sciiimentologic data. Hoyt (1967) had made a compelling case

for barrier islands formiiijz by submcrycncc ofcoaista! dtmcs or

beach ridges due to rising sea level (Figure B5). However, in

1968.

John Fisher produced a critical review o\' the submer-

gence theory pointing out that long, straight, and continuous

dune ridges would not occur along a coast being inundated by

rising sea level. In light of Ihese observations. Fisher became a

strong proponent of Gilberts spit accretion theory.

Recent barrier island research

Since ihe late-1960s there have been many studies of barrier

islands aimed al determining the sedimentary layers making up

the barrier and deciphering the manner in which these layers

were deposited. This research has been aided by ihe radio-

metric dating of organic material contained within the barriers

sediments, such as shells, peat, and wood, thereby providing a

chronology of barrier construction (Davis, 1994), In addition

to traditional stratigraphic techniques, ground-penetrating

radar (GPR) is also employed to study barriers (Jol cl al.,

1996;

van Heteren etal.. 1998). Sediment cores are taken in

conJLinclion with the GPR surveys lo detennine the composi-

tion of the sediment layers and the environment in which they

v\ere deposited. Additional information concerning former

barriers and their associated tidal inlets and lagoons has been

gathered from the inner continental shelf using high- resolu-

tion shallow seismic surveys, a technology similar in principle

to GPR, These advancements have provided new insights

about the formation of coastal barrier systems.

Scientists are beginning to accept the idea that barriers can

form by a number of different mechanisms. In considering the

formation ol' barrier islands, it is important to recognize that

almost all the worlds barriers are less than 6.500 years old and

most are younger than 4,000 years old. Most barriers formed

in a regime of rising sea level but during a time when the rate

of rise began lo slow. Sedimentological data from the inner

continental shelves off the East Coast of the United States, in

the North Sea, and in southeast Australia suggest that barriers

once existed offshore and have migrated to their present

positions,

Morphosedimentary barrier types

The overall form oC barriers, iheir stability, and future

erosional or depositional trends are related to the supply of

sediment, the rate of sea-level rise, stonn cycles, and the

topography oi' the mainland. When a barrier builds in a

seaward direetion it is said to prograde and is called a pro-

^railin\i barrier, Prograding barriers ibrni in a regime of

abundant sand supply during a period of stable or slow rise in

sea level. The sand to build these barriers may come from

along the shore or from offshore sources. These conditions

were met along much of the East Coast of the United States

and many other regions of the world about 4,000 to

5.000

years ago when the rate of sea-level rise decreased and

sediment was eontributed to the shore from erodinghcadhutils

(examples: Provinceland Spit in northern Cape Cod. Massa-

chusetts (Fit/Gerald etal.. 1994): Lawrencetown barrier along

the Northeast Shore of Nova Scotia), from the inner continen-

tal .shelf isxampla: barrier system along Bogue Banks. North

Carolina; Algarve barrier chain, in southern Portugal;

Tuncurry barrier in southeast Australia (Roy

i.'t

a!.. 1994);

East lYiesian Islands along the German North Sea coast), and

ilirectiv front

rivers

(examples: most barrier systems in northern

New England; barrier chain situated north ol' the Columbia

River along southern coast ot" Washington),

A ri'lrogradin^ barrier forms when the supply of sand is

inadequate to keep pace with relative sea-level rise and/or with

sediment losses (Moslow and Colquhoun, 1981), Stated in

terms of

a

sediment budget, a barrier becomes retrogradational

when the amount of sand contributed to the barrier is less than

the voltime transported away from the barrier. The sand may

be lost offshore during storms, moved along shore in the

littoral system, or transported across the barrier by overwash.

Overwitsh is a cannibalistic process whereby stonn waves

transport sand from the beach through the dunes, depositing it

along the landward margin of the barrier {Figure B4), In this

way the barrier is preserved by retreating landward. Because

these barriers have been migrating over various types of

backbarrier settings, including lagoons and marshes, the

46

ISLANDS

RETROGRADATION (TRANSGRESSIVE STRATIGRAPHY)

0,5 km

semi-sheltered

emhaxnieut

time

time 2

A

PRQGRADATIQN (REGRESSIVE STRATIGRAPHY) AND AGGRADATION

\e'iyded

/ '

(Inimlin

and

reworked

glacial sand

Jime 2

SUREACE

CROSS SECTION

^

\. JL L

till-covered bedrock

unconsolidated

uphind

salt marsh

barrier/

tlood-tidai delta

water

upper (freshwater)

marsh

ebb-tidal delta

drumlin

till-covered bedrock

glacial and fluvial

facies

salt-marsh peat

sandy barrier facies

drumlin

lagoonal/estuarine

facies

freshwater peat

water

gravelly barrier

facies

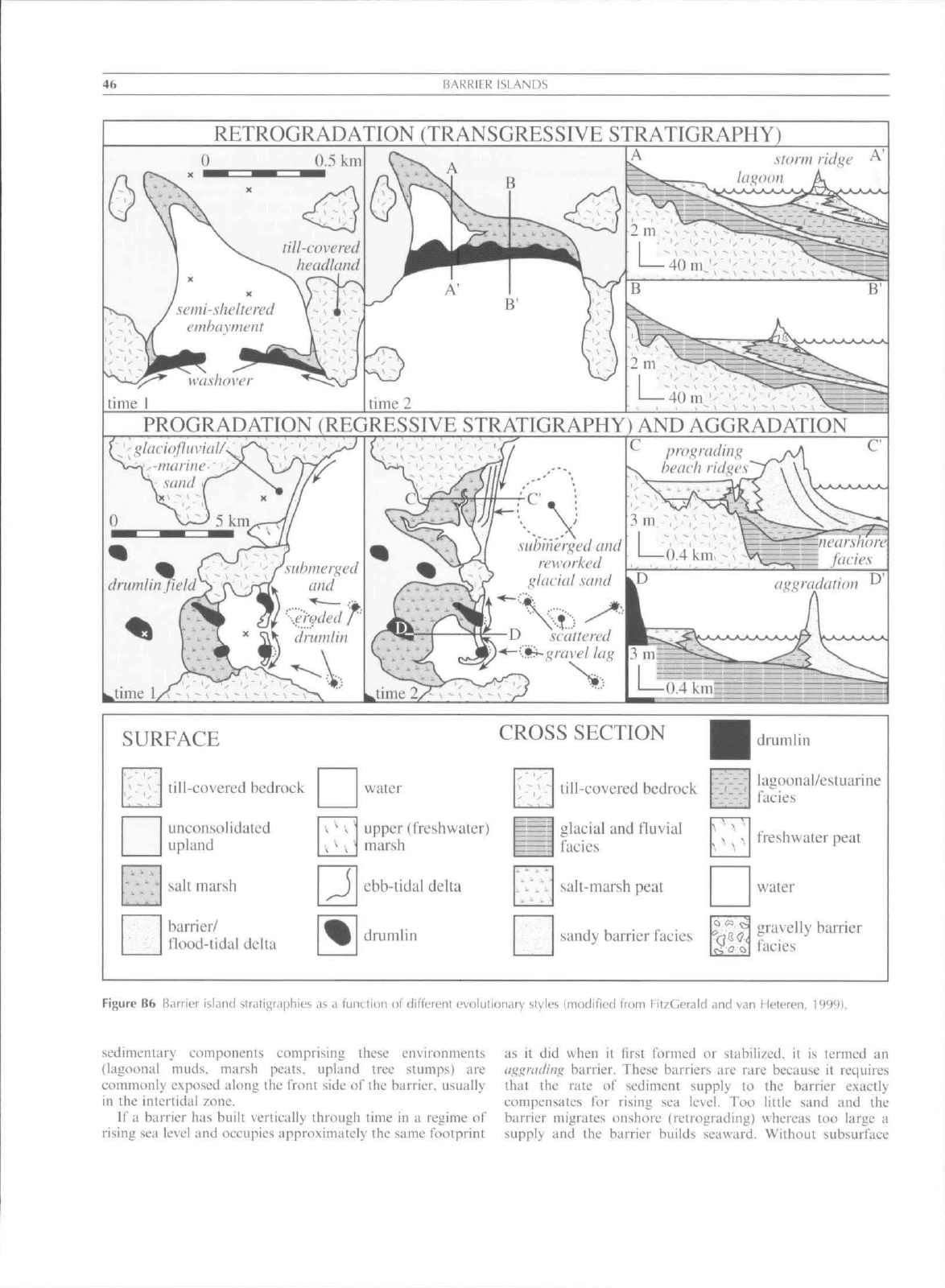

Figure

B6

Barrier isLincI stratigr,3phies

as a

tunctinn

ot

different evolutionary styles (modified from FilzGeriild and van Heleren, 1999|.

sedimenlary components comprising these environments

(lagoonal muds, marsh peats, upland tree stumps)

are

commonly exposed along

the

front side

of

the barrier, usually

in

the

intertidal zone.

If

a

barrier

has

built vertically through time

in a

regime

of

rising

sea

level

and

occupies approximately

the

same footprint

as

it did

when

it

first formed

or

stabihzed.

it is

termed

an

aggrading barrier. These barriers

are

rare because

it

requires

that

the

rate

of

seditiient supply

to the

barrier exactly

compensates

for

rising

sea

level.

Too

little sand

and the

barrier migrates onshore (retrograding) whereas

too

targe

a

supply

and the

barrier builds seaward, Williout subsurface

BARRlIrK ISLANDS

47

intbrmation they arc difficult to recognize, because morpho-

logically they may appear similar to non-beach ridge,

prograding barrier or even a retrograding barrier that has

stopped moving onshore.

Barrier island stratigraphy

Barriers exhibit a variety o!' arehiteetures consisting of many

different types of sedimentary sequences depending upon their

evolutionary developnieni. The stratigraphy of a barrier is

defined by a set of grain size, mineralogical. and other

characteristics of the layers comprising the barrier deposit.

Factors sueh as sediment supply, rate of sea-level rise, wave

and tidal energy, climate, and topography of the land dictate

how a barrier develops and its restilting stratigraphy. Another

important factor affecting barrier ihiekness is accommodation

space which defines how much room is available for the

accumulation of barrier sands.

Barrier sequences often contain tidal inlet deposits, espe-

cially along barrier coasts where tidal inlets open and close

and/or uherc tidal inlet migration is an active process

(Reinson. 1984. 1992). A tidal inlet migrates by eroding the

downdrift side of its channel while at the same time sand is

added (o the updrift side of its ehannel. In this way. the updrift

barrier elongates, the downdrifi barrier retreats, and the

migrating inlet leaves behind channel till deposits underlying

!he updrift barrier. Independent studies along New Jersey and

the Delmarva Peninsula, North Carolina, and South Carolina

Indicate that 20 percent to 40 percent of these barrier coasts are

underlain by tidal inlet fill deposits

f

Moslow and Heron, 1978),

fiach morphosedimentary barrier type has a diagnostie

stratigraphy that rellects the manner in which it developed

(Figure B6), Prograding barriers typically exhibit regressive

stratigraphy, Becau.se this type o\' barrier builds in a seaward

direction, the barrier sequence is commonly thick (10-20m)

and o\erlies offshore deposits, usually composed of fine-

grained sands and silts (Bernard ci al.. 1970), The barrier

sequence consists of nearshore sands, overlain by beach

deposits, and topped by dune sands. The contacts between

the units are gradational and for the most part the sedimentary

sequence coarsens upward e,\eept for the uppermost fine-

grained dune sands. The retrograding barrier type migrates in

a landward direction over the marsh and lagoon by overwash

ptocesses. resulting In a

irttn.'igrc.s.sivc

stratigraphic sequence

(Kraft and John. 1979). The Holoeene sequence typically

bottoms in lagoonal muds, however, if the barrier has

retreated far enough landward, mainland deposits may be

preserved forming the base of the sequenee. In these instances,

we may find tree stumps, soils, and other deposits. The

mainland units are overlain by backbarrier sediments inelud-

iny a variety of units such as lagooiial silts and clays and marsh

peats which had formed in intertidal areas. In the vicinity of

tidal inlels. backbarrier deposits consist of channel and flood-

tidal delta sands. Overlying the backbarrier deposits is the thin

barrier sequence (<3m to 4m) consisting of washovers. beach

deposits, and dune sediments if they are present. Aggrading

barriers build upward in a regime of rising sea level and in an

ideal case, the deposits from the same environmental setting

are staeked vertically. In most cases, however, the barrier has

shifted slightly landward and .seaward through time due to

changes in sediment supply and rates of sea-level rise.

Therefore, most aggrading barriers exhibit some interstacking

of various units. For example, in the rear of the barrier the

sequence may consist of washover and dune units inter-layered

with marsh and lagoonal deposits. Aggrading barriers tend to

be thick (lOm to 20m) and for reasons stated previously, are

uneommon.

Duncan M, Fit/Gerald and Ilva V. Buvnevich

Bibliography

Bmuird. II,A,. Major. C.F.. Parrolt, B.S,. and LoBlanc. R,J,. 1970.

Rfceiit sediments of Southciisi Texas: a lield guide Io Ihe Brazos

alluvial and deltaic plains and tht: Galvcston barrier island

complex. Univ. of Texas

—

Austin. Bureau of Economic Geology,

Guidehotik

No.

II.

Davis.

R.A. Jr. (ed.). 1994,

Gealojyy

of Holi'ccnc harrier island Systems.

Springer-Verlag.

I'ii/fieratd, D,M^ Rosen, P,S,. and van Heteren. S,, 1994.

New HngUtnd barriers. In Davis, R,A. Jr, (ed,), (leoloay ol Holo-

cenc

Harrier

Island Systems. Springer-Verlag, pp, ?()5-394,

FitzGerald, D,M., and van Heteren. S,, 1999. Classificalion of

paraglacial barrier systems: eoaslal New Fiigland, LIS,A, Scdinien-

loloiiy.Ad: 10S.1 1108,

Have?.,

M,O,. 1979, Barrier ishiiid morphology as a function of lidal

and wave regime. In Leatherman, S.P, (ed.). Barrier islands:Jnmi

the Gulf of

SI.

Luwreiuc lo

IIH-

(iidfi-t Mexico. New York: Academic

Press,

pp, 1-28,

llovt. J.H,, 1967, Barrier island formmioii, Gcoloi-icidSociclvnf.inicr-

'iai Bulletin. 78: 1123-1136,

Inman. D,L,, and Nordstrom. C.E.. 1971, On the tectonic and

morpholojiic elassilication of coasts. Journal of Gcoloi:v. 79: I 21.

Jol.

H,M,, Smiih. D.G,, iind Meycis, R.A,, 1996, Digital ground

penetrating radar (GPR): an improved and very etfeclivc geophy-

sical lool for studying modern coastal barriers (examples for the

Atlantic. Gulf and Pacific coasts. U.S,A,), Journal iif

Coa.slal

Re-

search. 12: 960 96X,

Kraft. J,C., and John. C,J,. 1979, Lateral and verlical facies relations

of transgressivo barriers, Bnllerin of American

.'Association

cfPetro-

leionGealoiii.sl.s.

63: 2145 2163,

Featherman. S,P., 1979, Barrier island Handbook. Amherst,

Massachusclts.

Moslow. T,F,. and Heron, S,D,, 1978, Relict inlets: preser\iition and

occurrence in the Holoeene stratigraphy ol southern Core Banks,

Nortii Carolina, .fourmdo/ Sedimenlary Petniloi:y. 48: 1275 I2S6,

Moslow, T,F,, and Colquhoun. D.J,. 1981, Influence of sea-leve!

change on barrier island evolution. Oceanis. 7: 439-454,

Peniand. S,. and Boyd. R,, 1985, Transgressivc depositiona! envlron-

ment.s ot~ ihe Mississippi River Delia plain: a guide lo the barrier

islands, beaches, and shoals of Louisiana, Baton Rotige, LA,

i-ouisiitno GeologicalSnr\ey. Guidehuok

Serie.\

#.^,

Reinson, G.F,. I9K4, Harrier island and associated strand-plain

systems. In Walker, R,G, (cd,),

Faeies

.\fodels. Cieoscience Canada

Reprini Series 1: pp, 119-140,

Reinson. G,E,, 1992, Tiansgressi\e barrier island and esiuarine

systems. In Walker, R,G,. and James, N,P, (eds,), Facies Models:

Re.spon.se

lo Sea Level Change. Geological Association of Canada,

pp,

179-194.

Roy, P,S.. Cowell, P,J,. Ferlitnd, M.A,, and Thom, B.G., 1994, Wave-

dominalecl coasts. In Carter. R,W.G,. and WoodrolTe. CD, (eds,),

Cnaskd tAiihitiiin: Late Quaternary slunvline niurphodynaniies.

Cambridge University Press, pp, 121 1!^6.

Schwart7, M,L,, 1973, Barrier i.slands. Slroudsburg, PA: Dowdcn,

Huichin.soii and Ross,

VLin Heteren, S,, Fitz(}erald, D,M,. McKiiilay, P,A,. and Buynevich.

LV,. lyyS, Radar facies of paraglacial barrier systems: coastal New

Fngland. USA. S<'(//»;c/i/<'/f<t'r.~45: 181 2llt).

Cross-references

Bar, Littoral

Tidal Inleis and Deltas

48

BAUXITF

BAUXITE

Introduction

BatixitL' is fotind in tnany parts of the world, but more

particularly in tropical areas. Bauxite is of supergene origin

commonly produced by weathering and leaching of silica from

aluminum bearing rocks. Bauxite may occur insiui as a direct

result

ot"

weathering or it may be transported and deposited in

sedimentary formation, Gibbsite [AI(OH)i], boehmite and

diaspore [AIO(OH)] are the three principal hydrates of

aluminum and form the main constituents of bauxite and

latcrites with gibbsite often being the predominant mineral.

Gibbsite or hydrargillite. bayerite and nordstrandite are all

polytypes of alumintim trihydroxide, Diaspore is a dimorph of

boehmite, Australian soils often contain gibbsite, particularly

in the soils of hot humid climates where the topography is

suitable for its accumulation as occurs in Northern Queens-

land. Gibbsite often occurs in association with kaolinite as

exemplified by the Weipa deposits of North Queensland

{Wilke and Schwertmann, 1977). Gibbsite is the end product

of granitic weathering and is formed from the diagenetic

sequence: plagiodase ^ amorphous or allophanic minerals -^

kaolinite -> gibbsite. Such a sequence shows why the impurity

in gibbsiles is often kaolinite. Australian bauxites arc

predominantly composed of mixtures of gibbsite and boehrnite

with no diaspore. Impurities include hematite, kaolinite.

quartz, and other derived minerals. The Weipa bauxite

composition varies from 70 percent to 95 percent gibbsite

and from 25 percent to 5 percent boehmite.

Thermal transformations

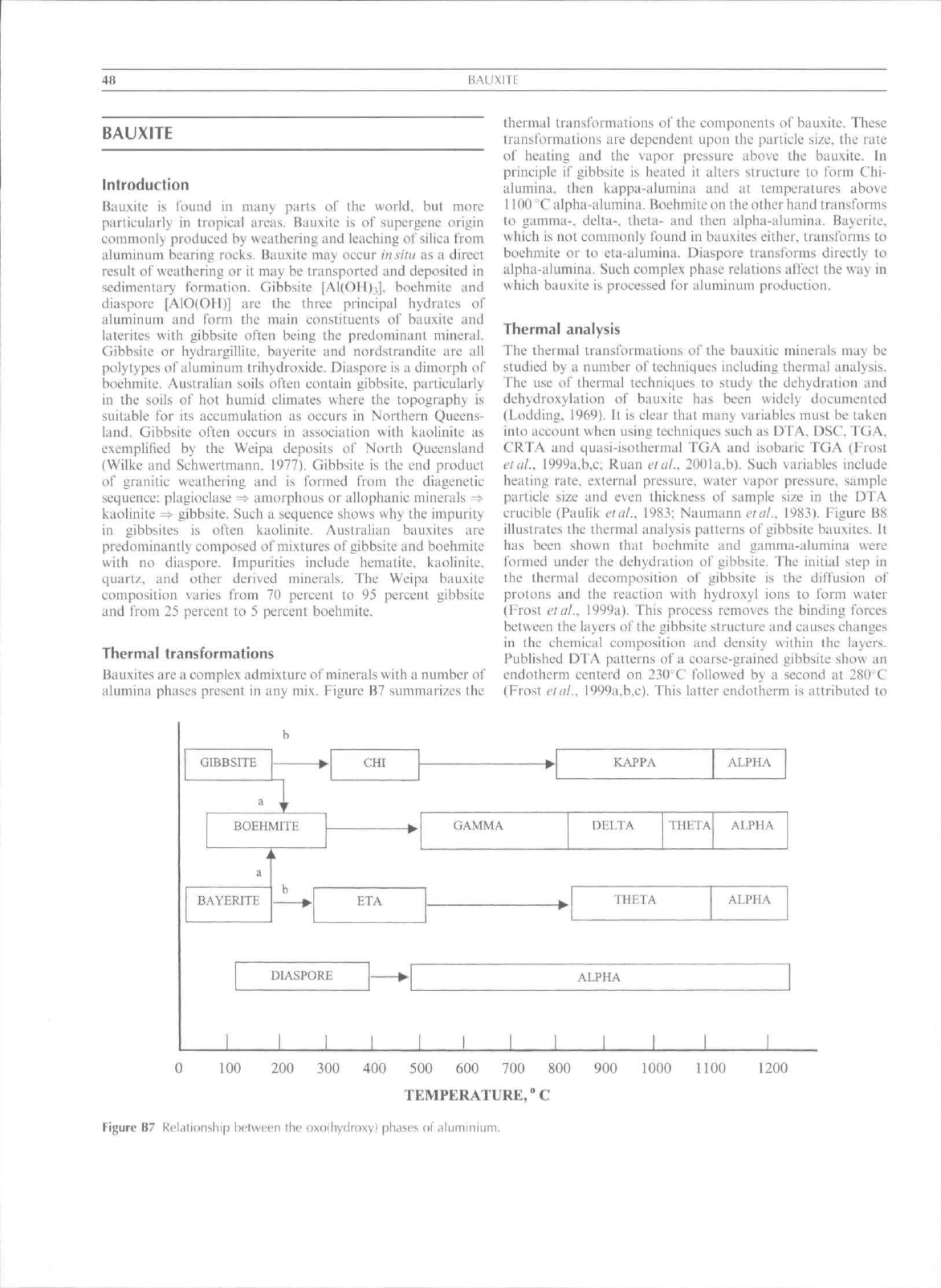

Bauxites are a complex admixture of minerals with a number oi'

alumina phases present in any mix. Figure B7 summarizes the

thermal transt^ormations of the components of bauxite. These

transformations are dependent upon the particle si/e. Uie rate

of heating aitd the vapor pressure above the bauxite. In

principle if gibbsite is heated it alters structure to form Chi-

alumina. then kappa-alumina and at temperatures above

1100'

C alpha-alumina. Boehmite on the other hand transforms

to gamma-, delta-, theta- and then alpha-alumina, Bayerite,

which is not commonly found in bauxites either, transforms to

boehmite or to eta-alumina, Diaspore transforms directly to

alpha-alumina. Such complex phase relations affeet the way in

whieh bauxite is processed for aluminum production.

Thermal analysis

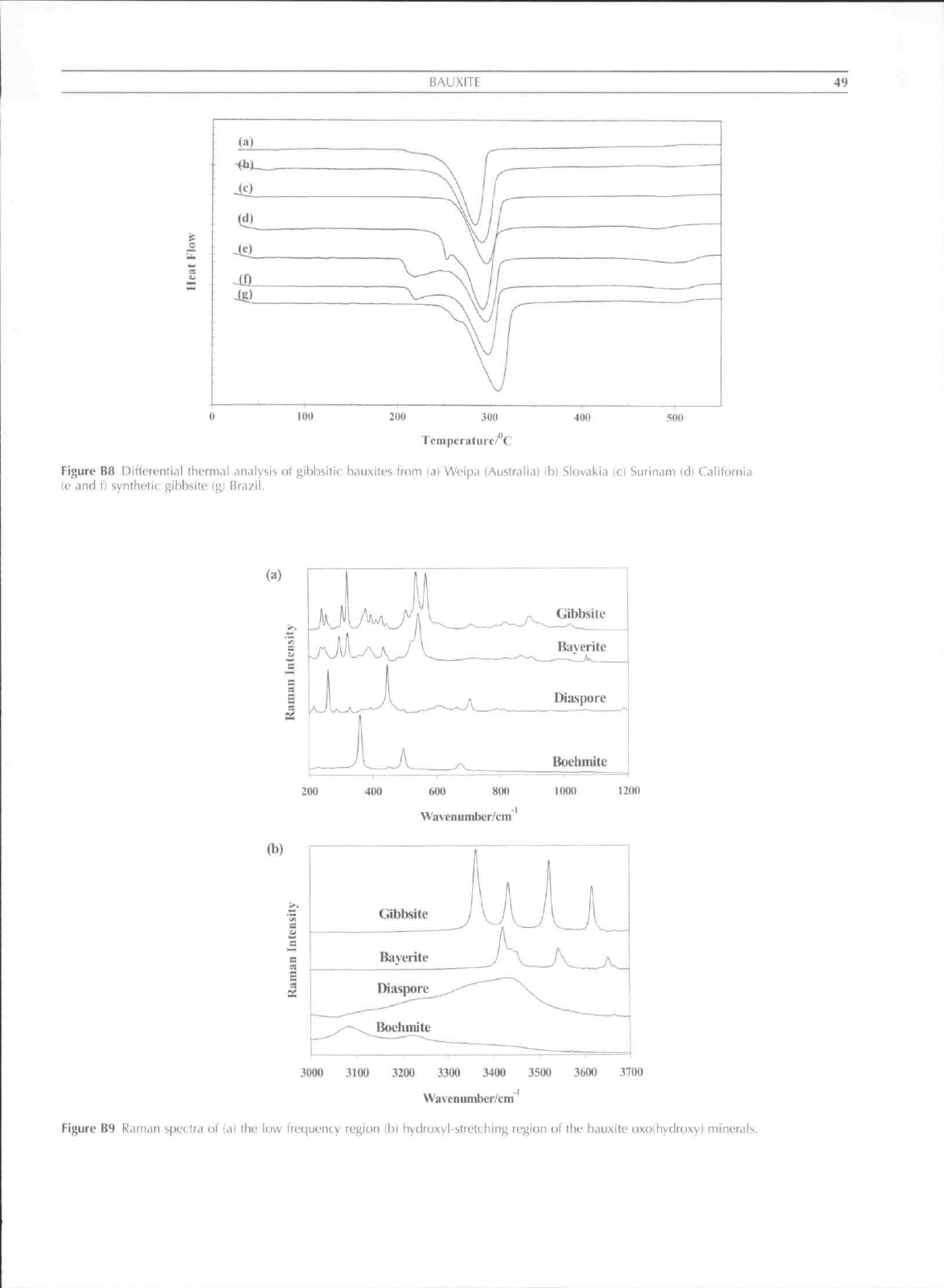

The thermal transfoimatlons of the bauxitic minerals may be

studied by a number of techniques including thermal analysis.

The use of thermal techniques to study the dehydration and

dehydroxylation oi' bauxite has been widely documented

(Lodding. 1969), It is elear that many variables must be taken

into aecount when using techniques such as DTA, DSC. TGA,

CRTA and quasi-isothermal TGA and isobaric TGA (Frost

cial.. 1999a.b.e: Ruan vta!.. 2noia.b). Such variables include

heating rate, external pressure, water vapor pressure, sample

particle size and even thickness of sample size in the DTA

crucible (Paulik etal.. 1983; Naumann

f/a/,.

1983), Figure B8

illustrates the thermal analysis patterns of gibbsite bauxites. It

has been shown that boehmite and gamma-alumina were

formed under the dehydration of gibbsite. The initial step in

the thermal decomposition of gibbsite is the diffusion of

protons and the reaction with hydroxyl ions to form water

(Frost cial.. 1999a). This process removes the binding forces

between the layers of the gibbsite structure and catises changes

in the chemical composition and density within the layers.

Published DTA patterns of a coarse-grained gibbsite show an

endothcrm ceiitcrd on

230"

C followed by a second at 280 C

(Frost etal.. 1999a.b.c). This latter endotherm is attributed to

GIBBSITE

CHI

KAPPA ALPHA

BOEHMITE

BAYERITE

GAMMA DELTA THETA ALPHA

ETA

THETA ALPHA

DIASPORE

ALPHA

0

100

200 300 400 500 600 700 800

TEMPERATURE," C

Figure B7 Relationship between the oxolhydroxyl phases ol aluminiiim.

900 1000 1100 1200

BAUXITE

49

100

200

300

Tempera tu

re/"

400 500

Figure

B8

Ditterentitil thcrm.Tl .ln.ilysis

ot"

j;ibbsitic bauxites from

[a]

Weipa lAustralia)

(b)

Slovakia

(ci

Surinam

(d)

Californi<i

if

and

I)

synlht'lii. gibbsite

(gl

Br.izil.

(b)

Boehmite

400

600 800 1000 1200

Wavenumber/cm

Gibbsite

3t)00

3100

3200 3300 3400 3500 3600 3700

Wavcnumber/cm

Figure B9 Raman spectra of lai the low frequency region lb) hydroxyl-slrctching region of the bauxite oxolhyclroxy) minerals.

BAUXITE

6200 6400 66OO 68OO 7»O0 7200 7400 7600 7800 801)0

Wavenumbfr/cm'

Figure BIO Near-IR spectra of the first hydroxyl stretching fundamental of the bauxitic minerals.

the formation of boehmite by hydrothermal conditions due to

tlie retardation diffusion of water otit of the larger grains. This

exothermic reaction does not occur in tite DTA patterns of

finely grained gibbsite. A shitllow endotherm may be observed

between 500' C and 550 C and is attributed to the formation

of boehmile. There is general agreement that boehmite and a

disordered transition alunaina are formed upon the thermal

treatment of coarse gibbsite up to 4()0-'C. When fine-grained

gibbsite is heated rapidly, an X-ray amorphous product

labeled rho-alumina is obtained.

Spectroscopic characterization of bauxites

One valuable suite of teehniques that are suited for the

eharaeterization of bauxites are based upon vibrational

speetroseopie techniques. These teehniques include those of

infrared including neai-IR (NIR). lar-IR. DRIFT speetro-

seopie teehniques, Raman spectroscopy is also useful in the

characterization of the bauxitic phases,

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy has the advantage that it is a scattering

technique, does not require sample preparation and is not

sensitive to ihe presence of water. The Raman speetrum of

gibbsite shows four strong, sharp bands at 3617, 3522, 3433

and 3364cm '. The speetrtim of bayerite shows seven bands at

3664.

3652. 3552. 3542. 3450. 3438. and 3420 em ' in the

hydroxyl-stretehing region. Five broad bands at 3445.

3363.

3226.

3119, and 2936 em ' and lour broad and weak bands at

3371.

3220, 3085, and 2989cm ' are present in the Raman

speetrum of the hydroxyl-stretching region of diaspore and

boehmite, respeetively. The hydroxyl-stretehing bands are

related to the surface strueture of the minerals. The Raman

spectra of bayerite. gibbsite. and diaspore are complex while

the Raman speelrum of boehmite only shows four bands in the

low wa\enumber region. These bands are assigned to

deibrmatlon and translational modes oi the alumina phases,

A comparison of the Raman speetrum of bauxite with those of

boehmite and gibbsite shows the possibility of using Ratnan

speetroseopy for online proeessing of bauxites.

Near infrared spectroscopy

Another most useful technique for studying bauxites and their

phase components is the reflectance technique of N!R

spectroscopy, NIR is known as the spectroscopy of protons

as .so as a consequence all phases containing water or hydroxyl

units ean be measured by NIR, This means that NIR is also

most useful in the online proeessing of bauxites. Figure B9

displays the first overtone of the fundatiiental vibrations of the

hydroxyl stretching vibrations,

NIR speetroseopy distinguishes between alumina 0x0 and

hydroxy phases. Two NIR speetral regions are identified for

ihis funetion: (a) the high frequeney region between 6400 cm '

and 7400cm"', attributed to the first overtone of the hydroxyl

stretching mode, and (b| the 4000 4800em ' region attributed

to the combination of the stretching and deformation modes

of the AlOH units. NIR spectroscopy allows the study and

differentiation of the hydroxy and oxo(hydroxy) alumina

phases, since each phase has its own characteristic spectrum.

The speetrum of bayerite resembles that of gibbsite whereas

the speetrum of boehmite is similar to that of diaspore.

Bayerite has four characteristic NIR bands at 7218, 7128,

6996.

and 6895 cm ', Gibbsite shows five major bands at 7151,

7052.

6958. 6898. and 6845 em '. Boehmite displays three

NIR bands at 7152. 7065. and 6960cm"', Diaspore shows a

prominent band at around 7176cm '. The use of NIR

refiectance speetroseopy to study alumina surfaces has wide

application, particularly with thin films and surfaces. The

technique is rapid and accurate, NIR, because of its sensitivity

can be used in refieetance mode for the on-line proeessing of

bauxitic minerals.

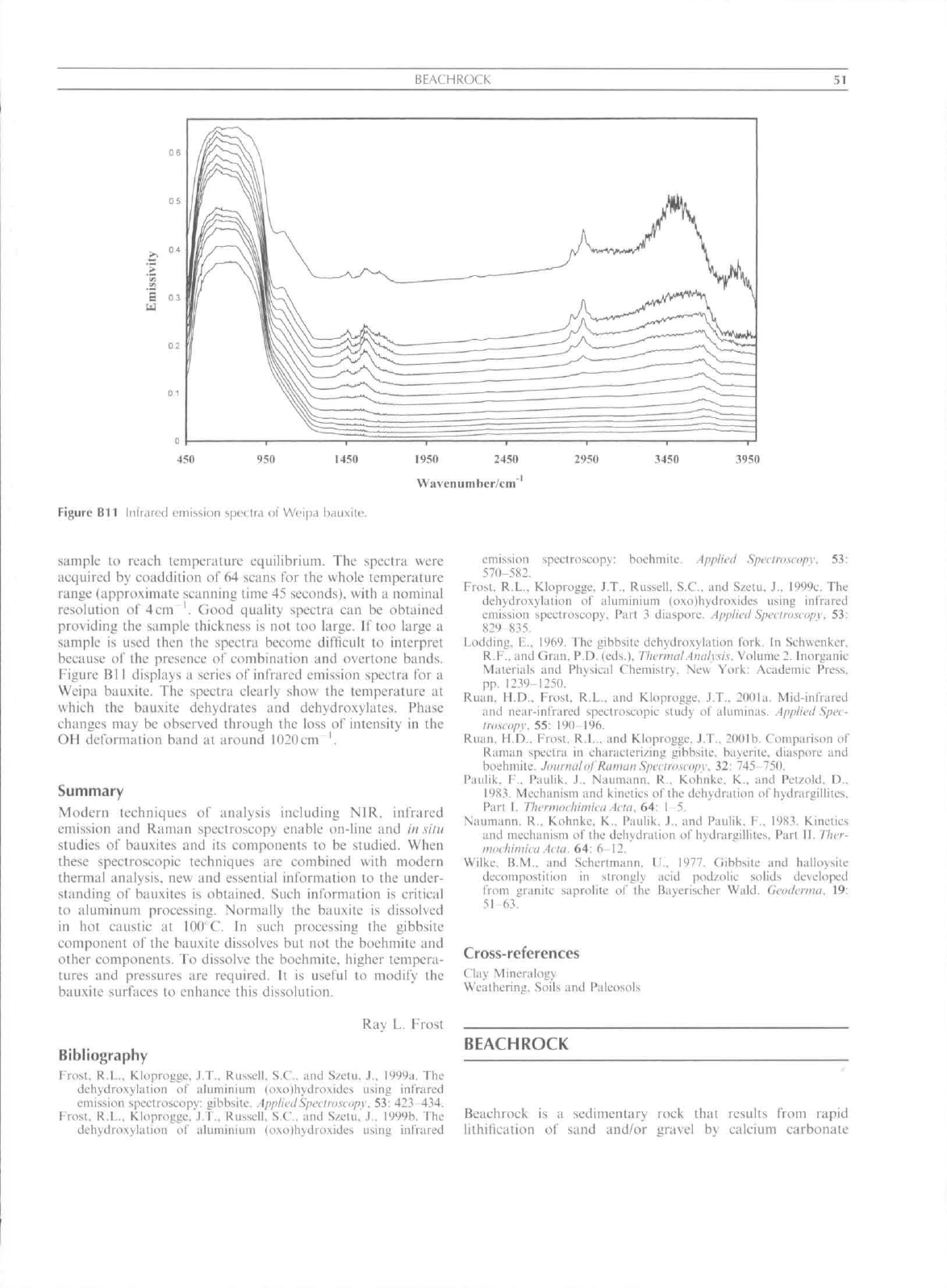

Infrared emission spectroscopy

Details of the experimental part of infrared emission spectro-

scopy have been detailed in a number o\' publications (Frost

cl al.. 1999a,b.c). The emission spectra were collected at

intervals of 5O'C over the range 200 750' C. The time between

seans (while the temperature was raised to the next hold point)

was approximately 100 seeonds. It was considered that this

was sufficient time for the heating bloek and the powdered

BEACHKOCK

450

95(1 1450

1950

2450

2950

3450

.1950

Wavenumber/cm

Figure

BIT

Intrared emission spettra

of

Weipa bauxite.

sample

to

reach temperature equilibrium.

The

spectra were

acquired

by

eoaddition

of 64

scans

for the

whole temperature

range {approximate scanning time 45 seconds), with

a

nominal

resolution

of

4ctii

'.

Good quality spectra

can be

obtained

providing

the

sample thickness

is not too

large.

If too

large

a

sample

is

used then

the

speetra become difficult

to

interpret

because

o\' the

prcsL'nce o\' combination

and

overtone bands,

I igure

Bl

I displays

a

series

o['

infrared emission spectra

for a

Weipa bauxite.

The

spectra clearly show

the

tcmpci"ature

at

which

the

bauxite dehydrates attd dehydt"oxylates. Phase

changes

may be

observed through

the

loss

of

intensity

in the

OH deformation band

at

around 1020 cm

',

Summary

Modern lechniqties

of

analysis incltiding

NIR.

infrared

emission

and

Raman spectroscopy enable on-line

and in

situ

studies

of

bauxites

and its

components

to be

studied. When

these spectroscopic techniques

are

combined with modern

thermal analysis,

new and

essential inl"orn"iation

to the

under-

standing

of

bauxiles

is

obtained. Such inftirmatitin

is

critical

to aluminum proeessing. Normally

the

bauxite

is

dissolved

in

hot

caustic

at

100'C,

In

such processing

the

gibbsite

component

of the

bauxite dissolves

but not the

boehmite

and

other components.

To

dissolve

the

boehmite. higher tempera-

tures

and

pressures

are

required.

It is

useful

to

modify

the

bauxite surfaces

to

enhance this dissolution.

emission spectroscopy: boehmile. .Applied Specirosctipv.

53:

570-582,

Frost.

R,L,.

Kloprogge.

J.T,.

Rus.sell.

S,C,.

iitid Szetu.

J,.

I'^Wc.

The

deliydroxylation

of

aliimitiiuin (oxo)liydroxides using inlrared

emission spectroscopy. Part

3

diaspore,

.Applied

Speetmseopy.

53:

829-835,

Lodding.

E,. 1%9, The

gibbsite dehydroxylation fork.

In

Schwenker.

R,K,,

and

tiraii. P,D, (eds,). Thermal.Analysi.s. Vokimc 2, Inorganic-

Materials

and

Physical Chemistry.

New

York: Academic Press.

pp.

1239-1250.

Ruan.

H,D,.

Frosi,

R.L,. and

Kloprogge.

J,T,.

2001a. Mid-inlrared

and near-inlrared spectroscopic study

ot

aluminas. Applied Spec-

troscopy.

55: 190 196,

Ruan.

H.D,.

Frosl.

R.L,.

;irid Kloprogge.

J,T,.

2001b, Cotnparison

of

Ramiui spectra

in

chiiracteri/ing gibbsite. bayeriie, diaspore

and

boehmite, Jinirnalnl Raman Spectrosciipy.

32:

745-750,

Paulik.

f\.

Paulik.

J..

Naumann.

R,.

Kohnke.

K,.

asid Pct/old.

D..

I9S3,

Mechanism

and

kinetics ollhc dehydriition ol'hydraigilliles.

Part

I,

Ihermorliimiea.kla.

64: ! 5,

Naumann.

R,,

Kohnke.

K,,

Piiulik,

J .

and

Paulik,

I..

I9K3,

Kinetics

and meehimism ol' ihe dehvdralion

ol'

hvdnirgiUilos. Piiri

II,

Ther-

niochimica

Ada. 64: 6-12,

Wilke.

B,M,. and

Scherlm;mn,

U.. 1977,

Gibbsite

and

halloysite

decomposlition

in

strongly acid pod/olic solids developed

Irom granilc saprolile

of ihe

Bayeriseher Wald. Geoilerma.

19:

51

63,

Cross-references

Clay Mineralogy

Weatherint!. Soils

and

Paleosols

Ray

L,

Frost

Bibliography

1

roM. R,L,.

Kloprogge.

J,T,,

Russdl.

S,C,. and

S/eiu.

.1,.

1999a.

The

dehydroxylalion

of

ahitiiinium (oxo)hydro\ides using infrared

emission speetroseopy: iiibbsite. AppliedSpeetroscopv. 53:

423 434,

FroM.

R.L,,

Kloprogge.'j,t,, Russell,

S,t\. and

S/etu,

J,.

I999h,

The

dehydro,\ylation

ol'

aluminium (oxo)hydro\ides using infrared

BEACHROCK

Beachiock

is a

sedimentary roek that results from rapid

lithification

of

sand and/or gravel

by

calcium earbonate

52

BEAC'HROCK

cements in the intertidal zone. It occurs predominantli on

tropical eoasts. but is also found as far north and south as 60'

latitude. In contrast to the implieations of the name, beachroek

outerops are not restricted to beaches but some are found on

tidal flats, in tidal channels, and on reef ridges. To date the

origin of beaehrock is not fully understood having been

variously attributed to physieochemical precipitation, bio-

logieally indueed eementation. or a combination of both.

Occurrence, composition, texture, and cements

Beachrock exposures are lypieally patchy with bedded layers

that dip gently (<IO' ) toward the sea. Hopley (1986) suggested

that the largely intertidal oeeurrenee of beaehroek makes its

fossil oeeurrenee a potential indieator of sea level. Problems

with this approaeh inelude possible failure to reeognize other

deposits that might get cemented elose to sea level such as dune

calcarenitc, eolianite. or cay sandstone (carbonate sand

cemenled by calciun"! carbonate from fresh water above high

tide level on reef islands), especially when diagenetic environ-

ments frequently changed, and the faet that radiometric dating

of beaehroek ean only produce an average age of the

constituent partieles and cements.

The eomposition of beaehroek constituent particles is more

or less similar to that of the adjacent consolidated sediment.

Grain-size ranges from sand to gravel: sediments are moderate

to very well sorted, with sorting usually better than that of the

adjacent subtidal sediments.

Beachrock cements are dominated by aragonite and high-

magnesium caleitc. The aragonite cement includes isopachous

fringes of needles that are up to lOO^m long, and often overlie

a dark layer at their base that consists of aragonite platelets

rieh in iron and sulfur (Strasser etal.. 1989). Small aragonite

(<lfl|-im long) needles n"iay form "mieritie" cement (e.g.. Webb

etal.. 1999), High-n"iagnesium calcite cements often include

mieroerystalline C'liiicritic'") cement with crystals less than

5|.im in diameter. Less common are cement fringes of high-

magnesium calcite blades or scalenohedral crystals (up to

70 Jim long). Petoidal eements with approximately 40 pm

diameter peloids. and equant crystal crusts of high-magnesium

caleite also occasionally oecur. Cements indicative of the

vadose diagenetie environment are eneountered rarely and

these result from eementation in the wave spray zone or during

low tide exposure. In this case, typical meniscus or gravita-

tional ("dripstone"') cement fabrics arc common. Detailed

deseriptions of beachrock eements are provided in IJricker

(1971:

I 43). Moore (1973). Meyers (1987). Strasser el al.

(1989),

and Gisehler and Lomando (1997) among others,

Scoffin and Stoddart (1983) provided a eomprehensive review

on beachrock and intertidal eementation up to that titne.

Origin

Early 19th century reports on beachrock confirm its rapid

formation in the intertidal zone (e,g,, Moresby, 1835), For

example, natives to Indo-Paciflc islands were known to harvest

beaehroek for building stone where new occurrences formed

on the same beach within less than a year. High resolution

radiometrie dating of cements in eoral reef slopes have shown

that marine aragonite eements. comparable to those observed

in beaehroek. reach growth rates of 80-100).mi per year

(Grammer etal.. 1993),

The mechanisms used to explain beachroek eementation

include both physieochemical and biologically induced pre-

cipitation of calcium earbonate. Physieochemical rnodels

explain precipitation of carbonate cement by evaporation of

seawater during low tide (e,g,. Ginsburg. 1953: Hanor. 1978).

and by degassing of CO^ during falling tides (Meyers, 1987) or

during higher tides (Pigott and Trumbiy. 1985). Apart from

CO2 pore water saturation states, water agitation is probably

another important factor in beachroek formation. A large

scale study on Belize beaehroek showed that the vast majority

of beachrock exposures occured on windward beaehes of reef

islands, suggesting that beachrock cementation only occurred

where beaehes experieneed intensive and persistent flushing by

seawater (Gisehler and Lomando, 1997). Variations in pore

water pressure during pumping of seawater through the beach

may also lead to calcium carbonate precipitation, Beaehrock

fortnation in Grand Cayman island was interpreted by Moore

(197?) to be largely a product of cementation under mixed

meteoric-marine conditions. In contrast. Hanor (1978) used

thermodynamic calculations to show that precipitation of

beachrock cement cannot be indueed by mixing of marine

and tneteorie water. Rather, these calculations favor CO2

degassing as a means of supersaturating pore-water

with calcium carbonate to the point of inducing cement

precipitation.

There is also evidence suggesting the importance of

biological proeesses in beaehroek tbrmation. Algal eoatings

may form on the beach, and stabilize grains so that they can be

preferentially cemented (Davies and Kinsey. 1973), With-

drawal of CO2 by photosynthesis may furthermore induce

calcium earbonate preeipitation. Krumbein (1979) noted the

occurrence of high concentrations of organic matter during

initial stages of beachrock formation in the Guif of Aqaba and

suggested that anaerobie and later aerobic decay processes

were responsible for cement precipitation, Deeay processes

may include ammonification leading to higher pH. or sulfate

reduction that elevates alkalinity, or hydrolysis of urea

forming ammonium carbonate and eventually calcium carbo-

nate.

Further suggestions of a biologieal influence on

beachrock formation arc provided by Webb etal. (1999),

These workers found microbial fllaments in both beachrock

cement and microbialites within beachrock cavities on Heron

Island, Great Barrier

Reef.

They stressed the importance of

aeid organic macromoiecules with Ca"' binding carboxyl

groups in biofilms in forming nucleation zones for cements.

The common dark zones at the base of isopachous fringes of

aeicular aragonite beaehrock cement may reflect the occur-

rence of organie mueus (Davies and Kinsey, 1973), According

to the SFM study of Chafetz (1986), nuclei of marine peloids.

whieh may also form beaehroek cement, are composed of

bacterial clumps.

Open questions remain with regard to the formation of

beachrock. If physieochemical (inorganic) proeesses are

suffieient to induce ealeium carbonate eementation. why are

beachrock outcrops so patchy in distribution, even on the

windward beaches of reef Islands? The same patchy distribu-

tion argues against organic proeesses as a pre-requisite for

precipitation of CaCO^ eement. unless and until it can be

shown that specific organic processes are pectiliar to beachrock

formation and therefore are not ubiquitous in oeeurrenee as

is the presence of microbes. It would seem that aspeets of

both inorganie and organic processes have to be taken

into aeeount to explain the origin of beachrock. To date.

BEDDING AND INTERNAL STRUCTURES

53

however, exclusively inorganic or exclusively organie models

do not suffice to explain the distribution of intertidal marine

cementation.

There are only very few reports on fossil, pre-Holocene

occurrences of beachrock, which probably is to a large extent a

consequence of its poor preservation potential. As soon as

beachrock is exposed it becomes subject of intensive intertidal

erosion, so only in cases of rapid burial would beachrock

outcrops be preserved,

Eberhard Gisehler

Bibliography

Bricker, O,P, (ed.), 1971, Carbonate Cetnents. Baltimore: Johns

Hopkins Press,

Chafetz, H,S,, 1986, Marine peloids; a product of bacterially induced

precipitation of calcite. Journal of Seditnentary Petrologv, 56:

812-817.

Davies, P,J,, and Kinsey, D,W,, 1973, Organic and inorganic factors

in recent beachrock formation. Heron Island, Great Barrier Reef

Journalof Sedimentary Petrology, 43:

59-81,

Ginsburg, R.N., 1953. Beachrock in south Florida. Journal of Sedi-

mentary Petrology, 23: 85-92,

Gisehler, E,, and Lomando, A,J., 1997. Holoeene cemented beach

deposits in Belize, Sedimentary Geology, ltO: 277-297.

Grammer, G.M., Ginsburg, R.N,, Swart, P.K., McNeill, D,F., Jull,

A,J,, and Prezbindowsky, D,R,, 1993, Rapid growth rates of

syndepositional marine aragonite eements in steep marginal slope

deposits, Bahamas and Belize, Journalof Seditnentary

Petrology,

63:

983-989,

Hanor, J,S,, 1978, Precipitation of beachrock cements: mixing of

marine and meteoric waters vs. C02-degassing, Journal of Sedi-

mentary Petrology, 48:

489-501,

Hopley, D., 1986. Beaehrock as sea-level indicator. In van de

Plassehe, O, (ed.). Sea-level Research. Great Yarmouth: Galliard

Printers, pp. 157-173,

Krumbein, W.E., 1979. Photolithotropic and chemoorganotrophic

activity of bacteria and algae as related to beachrock formation

and degradation (Gulf of Aqaba, Sinai), Journal of Geotnicro-

biotogy, 1: 139-203,

Meyers, J,H,, 1987, Marine vadose beaehroek eementation by

cryptoerystalline magnesian calcite-Maui, Hawaii, Jourtialof Sedi-

mentary Petrology, 57:

755-761,

Moore, C.H, Jr,, 1973, Intertidal carbonate cementation Grand

Cayman, West Indies. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 43:

591-602.

Moresby, R., 1835. Extracts from Commander Moresbys report on

the northern atolls of the Maldives, Journal of the Royal

Geographical

Society, 5: 398-404.

Pigott, J.D,, and Trumbiy, N,I,, 1985, Distribution and origin of

beachrock eements. Discovery Bay (Jamaica). Proceedings of the

5th International

Coral

Reef Sytnposiutn, Tahiti, 3: 241-247,

Scoffin, T,P,, and Stoddart, D,R,, 1983. Beachrock and inter-

tidal cements. In Goudie, A,S,, and Pye, K, (eds.), Chetnical

Seditnents and Geomorphotogy. London: Academic Press,

pp,

401-425.

Strasser, A., Davaud, E., and Jedoui, Y,, 1989, Carbonate eements in

Holoeene beachrock: example from Baihret el Biban, southeastern

Tunisia. Sedimentary Geology, 62: 89-100.

Webb, G,E,, Jell, J.S., and Baker, J.C, 1999, Cryptic intertidal

microbialites in beachrock. Heron Island, Great Barrier

Reef:

implieations for the origin of mieroerystalline beaehroek cement,

Seditnentary Geology, 126: 317-334.

Cross-references

Carbonate Mineralogy and Geochemistry

Cements and Cementation

Coastal Sedimentary Faeies

BEDDING AND INTERNAL STRUCTURES

Bedding

Bedding is the arrangement of sedimentary rocks in beds or

layers of varying thickness and character, A bed (or stratum) is

a relatively conformable succession of genetically related

laminae or lamina-sets (Campbell, 1967) bounded by surfaces

(called bedding surfaces) of erosion, nondeposition, or their

correlative conformities.

The bed is the smallest formal lithostratigraphic unit of

formal stratigraphy, and as such is defined solely on the basis

of its lithology, including color, grain size, and thickness, A

bed may range in thickness from a few millimeters to over

10

m, A key bed (or key horizon) is a well-defined, easily

identifiable stratum or body of strata that can be easily

distinguished from the overlying and underlying strata

by sufficiently distinctive characteristics, such as lithology,

thickness, texture or fossil content and their lateral gradients.

These allow physical tracing and stratigraphic correlation of

the key bed over long distances, up to several tens of km,

tn .seditnentology, the bed has a different, genetic connota-

tion: in other words, it represents a distinctive depositional

event, related to some processes or mechanisms of deposition.

In this meaning, a bed may show a change of lithology from

bottom to top, for example, from sand(stone) to mud(stone);

this is the case for most turbidites, storm layers (tempestites),

crevasse deposits, ete.

There exists a hierarchy of bedding in terms of scale,

geometry and spatial relationships of physical surfaces. This

hierarchy defines units of different rank, ranging from the

individual lamina to the basin-fill complex, and temporally

spans over a wide range of timeseales (from 10~^ years to 10

years).

Not always is the hierarchical arrangement recogniz-

able,

especially where the main bedding surfaces {tnaster bed-

ding) are obscured by superposition of lower-rank surfaces. In

this case, individual beds cannot be clearly identified and

counted, and only the bedding style, or pattern, is described

(e,g,, cross-bedding, sand/mud interbedding, clinoforms, etc),

with a rough specification of scale (small, medium, large).

The lamitia is the smallest sedimentation unit and is

characterized more by being a part of a bed than by its

thickness, although most laminae are in the submillimeter to

centimeter range, A single set of conformable laminae

(laminaset) may form a bed (solitary set and form-set of

J,R,L, Allen) or be a part of it: it can be associated either with

other laminasets in a wholly laminated bed or with structureless

(massive, graded) portions in a partly laminated bed (see

below, Bouma sequence). There exist also entirely structureless

beds,

which can be either emplaced by mass flows or have their

original structures destroyed by bioturbation or liquefaction

after deposition.

Bed packets or bundles distinct from those above and below

in a stratigraphic succession are called bedsets by Campbell

(1967);

within a bedset, there can be a dominant facies (i,e,, all

beds are similar in terms of lithology, thickness, texture,

structures) or a systematic vertical change corresponding to

a facies sequence (coarsening- or fining-up, thickening- or

thinning-up, etc), Bedsets are delimited by set boundaries and

form sedimentary bodies of simple or composite character.

54 BEDDING AND INTERNAL STRUCTURES

Repetitive bedsets can be grouped in eosets separated by coset

boundaries (base of the lowest set and top of the youngest).

The spatial arrangement of individual component bodies in

a complex body is called stacking pattern or architecture (Miall,

1985),

The term architecture is also applied to the intertial

organization of an individual body showing a hierarchy of

volumes and surfaces: in this case, an architectural element is

defined at each level of organization or rank. All such elements

have a faeies connotation, but the term facies is too often used

quite loosely because there is a lack of agreed-upon rules; for

the sake of clarity and communication, it is advisable to

specify at which rank the facies is defined, this being left to the

choice of the operator. After that, all smaller scale elements

will be sub-facies, all larger scale elements will he facies asso-

ciations. An example of facies can be a trough cross-bedded

sand(stone), representing bar crest deposits in a deltaic

depositional system. An example of facies association is a

mouth bar, for example, including bar back, bar crest, bar

front and distal bar facies.

When a facies association shows some kind of vertical order,

it is usually called a facies sequence. Lateral facies changes

are much less documented due to lack of sufficiently long

exposures; lateral transitions are rather inferred than observed,

with some notable exceptions (see Faeies Traets by Mutti,

1992),

Beds,

bedsets, architectural elements, facies, facies associa-

tions,

and stacking patterns are all three-dimensional units, but

for most practical purposes they can be recognized (or at least

inferred) and described in two (cross-sections), and even in one

(vertical profiles, well logs). The hierarchical classification of

depositional units and architectural scale concepts are thus

useful for basin analysis and the petroleum industry, since

reservoir geometry and internal heterogeneity may involve

different ranks and physical scales.

Internal structures

These are sedimentary structures located within beds or layers

and observable on surfaces cut at high angles to bedding

planes, that is, in normal stratigraphic sections. In clastic

deposits, most internal structures are physical, or purely

mechanical in origin, with the exception of trace fossils and

bioturbation (bio-mechanical). In carbonates, evaporites, cherts

and other sedimentary rocks of chemical and biochemical origin,

a color-compositional differentiation (e.g,, color banding) or

peculiar structures (e,g,, stromatolites, birds eyes, structures

related to crystal growth or dissolution) can be observed, but a

detailed description of them is not given here (see Diagenetie

Structures).

Attention will be focused here on mechanical struc-

tures.

They are subdivided into two main groups: those pro-

duced by transportation and deposition, and those resulting

from deformation soon after deposition (soft-sediment deforma-

tion as contrasted with tectonic or structural deformation).

Structures related to transportation processes

Most of these structures consist in geometrical arrangements

of laminae or kinds of lamination, and occur in sands and

sandstones; they are alsocalled tractive structures, traction

referring to bed-load movement of sedimentary particles.

Lamination can also be found in silty sediments, in which case

resulting from differential settling from suspensions. Lami-

nated or structureless mud(stone) can be associated in

alternating patterns with sand(stone); draping indicates a thin

muddy cover, laterally continuous or discontinuous, on sand

beds or an irregular topography. When traction is simulta-

neous with settling of silt and sand (which is put in suspension

by highly turbulent flows, such as turbidity currents), traction-

plus-fallout lamination forms (Jopling and Walker, 1968),

Local erosion is involved in the formation of tractive

structures, producing truncation surfaces and discordances of

various geometry and seale; some of them can be used for the

hierarchical differentiation of bedding. Tractive structures may

form when a current is in equilibrium (no net erosion or

deposition) with its lower boundary (sedimentary interface), or

in conditions of net deposition due to loss of carrying capacity.

In the former case, the result is a diastem or a single, thin bed

(solitary set, form-set with bedforms preserved on top: Allen)

of tractive laminae due to either a fresh sand supply or in situ

reworking of preexisting sand. Net deposition implies a higher

preservation potential of laminated intervals, even if the fiow is

oscillating and some erosion is produced; continuos feeding of

sand to the bottom not only buries previously deposited

laminae, but can build up decimeters or even meters of

laminated sediment (see the "Contessa" bed and other similar

"megaturbidites" in the Apennines of Italy),

Unidirectional flows

Tractive currents produce bedforms of various scales: small

(ripples), medium (subaqueous dunes), large (eolian dunes,

subaqueous bars and sandwaves), A set thickness of 4-5 cm

separates ripple from dune scale but no agreement exists for a

boundary between medium and large structures, Bedforms can

be extremely shallow or the bottom even and flat when the

Froude number is in excess of or near unity. One can thus

distinguish subcritical (lower fiow regime) from supercritical

tractive structures, and the distinction is applicable even at a

small scale (e,g,, core examination), because subcritical forms

have a separation zone at their lee side, where gravity

avalanching takes place Ae\e\opmg foresel laminae inclined at

the angle of repose of the sand (up to 30°-35°), Strata

therefore exhibit, in sections cut at a small angle with the fiow

direction, high angle lamination with respect to their bedding

planes. No fiow separation, and hence low angle lamination

(<IO°) characterizes supercritical bedforms. Low angle lami-

nae are not reliable indicators of current direction, whereas

foreset laminae are.

In case of a flat bottom, horizontal or plane-parallel latni-

nation occurs, A bed can part along weaker laminae showing

parting lineation (or primary current lineation), that is, slightly

terraced, shallow ridges formed by strips of sand grains aligned

parallel to the fiow. They are present also on low amplitude

bedforms of upper flow regime, such as antidunes and

humpback dunes.

At outcrop scale, the terms cross-bedding, cross-stratifica-

tion and cross-lamination are used when laminasets are bound

by nonparallel, intersecting surfaces; cross-bedding is the net

result of local deposition and erosion related to the migration

of bedforms (those of small and medium size are more

commonly represented in subaqueous deposits).

Cross-bedding should be qualified by specifications, for

example: (a) laminaset thickness as a scale indicator;

(b) presence or absence of foreset (high-angle) laminae, which

means lower or upper flow regime; (c) relation with master

bedding or other evidence of an original flat bottom;