Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

H

HEAVY MINERAL SHADOWS

First dcsciibcd

by

ChccI (!')84) from

the

Huvial facies

of the

Slkiriiin Whirlpool Sandstone

oC

southern Ontario, heavy

tTiJneral shadows

are

accumulations

of

dark heavy mineral

grains (e.g.. magnetite, leucoxene) that form

on

bedding

surfaces

of

predominantly quartz sand. Shadows have been

observed

on Hat.

planar surfaces associated with upper flow

regime plane beds (Cheel. 1984)

and on the

stoss sides

of

some

large dunes (Brady

and

Jobson. 1973).

The

accumulations

display

an

asymmetric gradient

in the

concentration

(Figures

HI and H2)

with

the

highest concentration

on the

upstream side

of the

shadow, decreasing

in the

downstream

direction. Observations

in a

flume indicated that shadows

migrate downstream

by the

periodic erosion

at

their upstream

edges with subsequent deposition

a

short distance down-

stream:

the

amount

of

heavy minerals that

are

deposited

decreases downstream, resulting

in the

downstream decrease

in

concentration

ot"

heavy minerals that characterize shadows.

Active heavy mineral shadows were observed

to be

overlain

by

much faster moving quartz-rich sand.

A

series

of

flume

experiments (Cheel.

1984)

suggested that heavy mineral

shadows were stable

at the

lower

end

(e.g.. lower velocity)

of

the upper plane

bed

stability Held

and

that they "washed

out""

as flow strength increased.

The main value

of

heavy mineral shadows

is

that they

can be

used

as

indicators

of

paleocurrent direction.

On

bedding

plane exposures

of

upper plane

bed

deposits (internally

displaying horizontal lamination), current (Allen.

1964) and

current iineation

FLOW DIRECTION

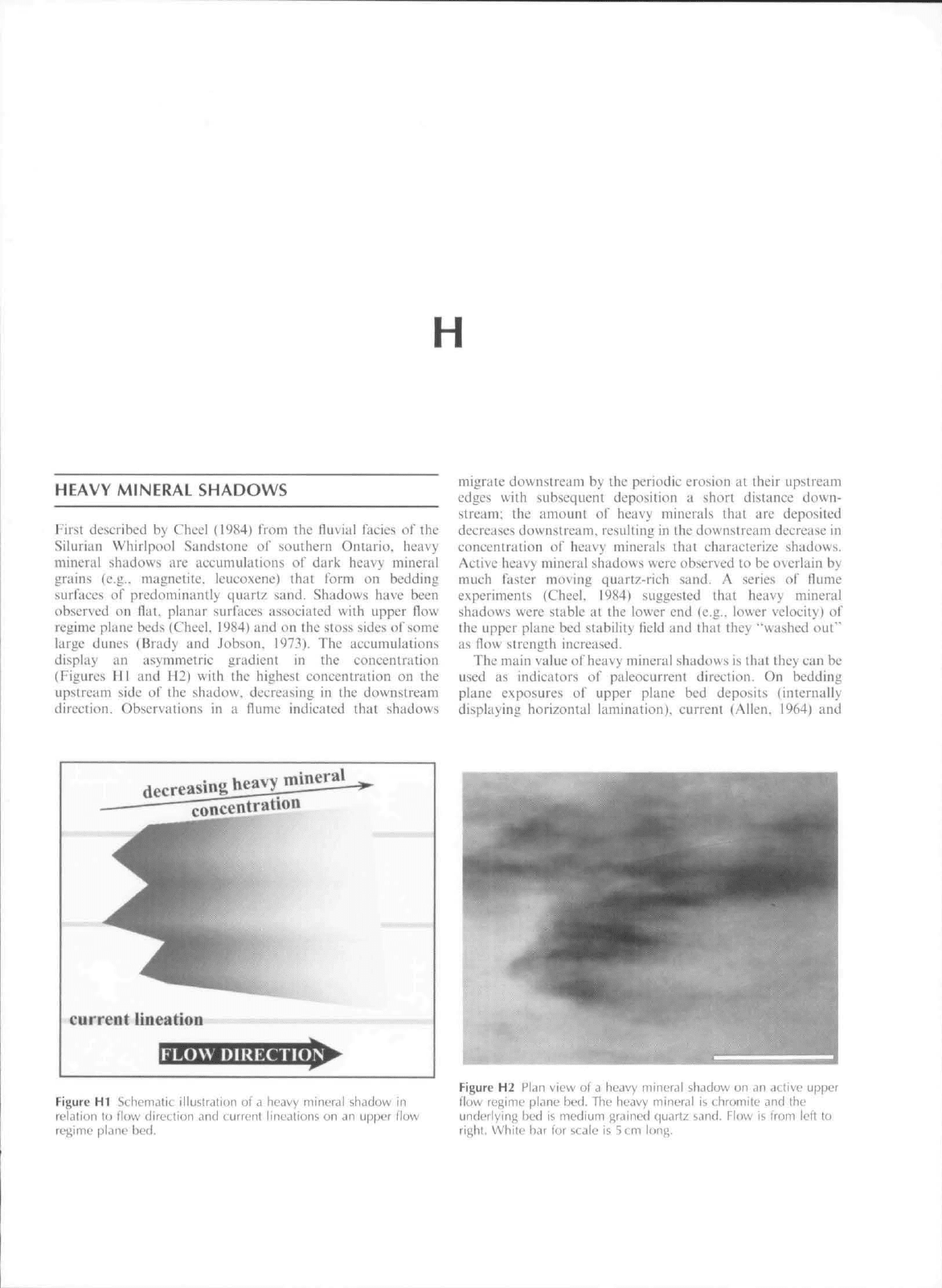

Figure

HI

SchenitUic illuslralicjn

oi a

heavy mineral shjdr;w

in

rclalion

if)

flow direction

and

current Imeations

on an

upper flow

regime pLine

bed.

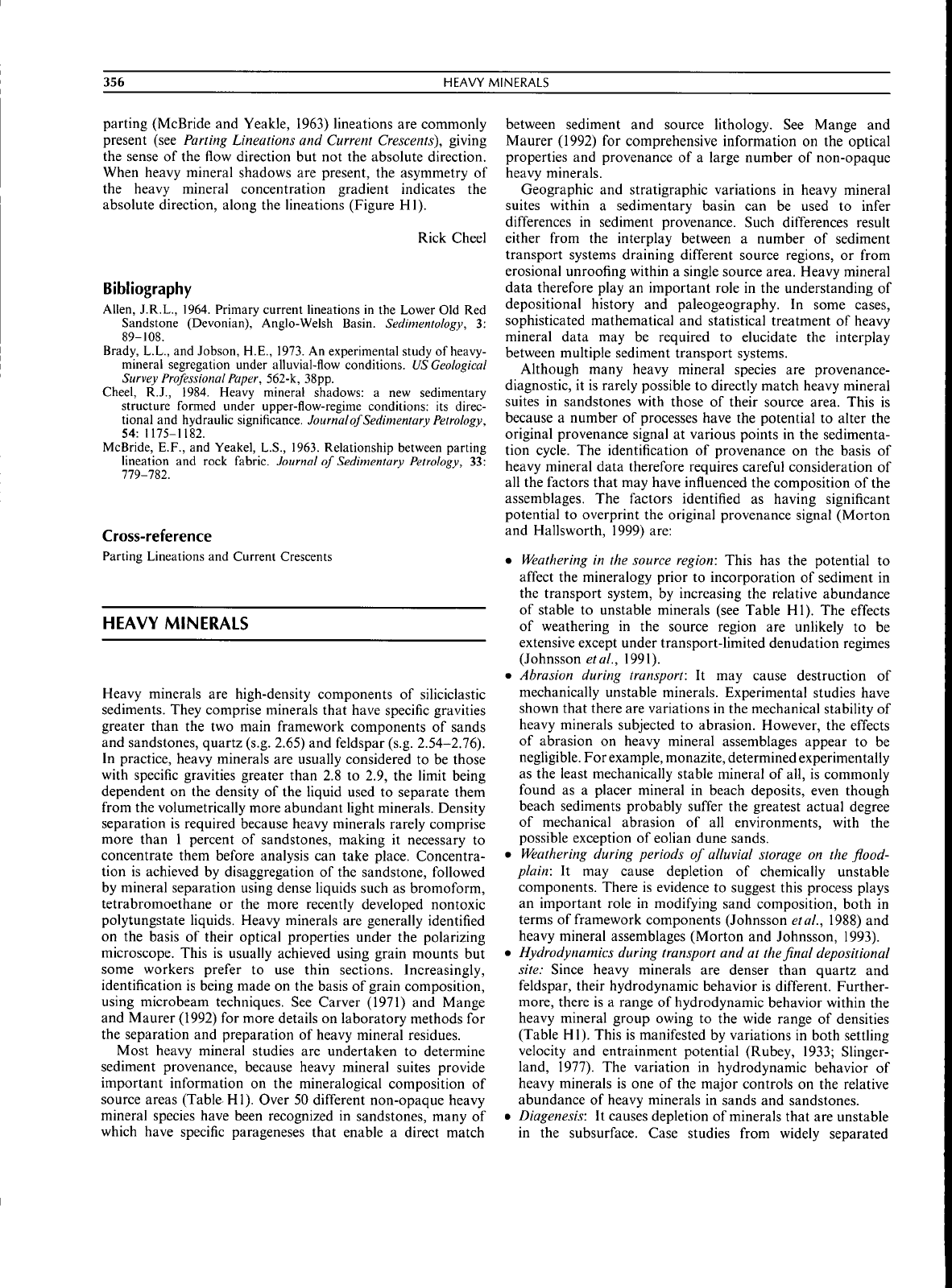

Figure

H2

Plan view

of

a heavy mineral shadow

on an

atlive upper

I'kiw

regime plane bed.

The

heavy mineral

is

chromite

and the

underlying bed

is

medium grained quartz sand. Flow

is

trom left

to

right. White

bar lor

scjie

is

5

cm

lung.

356

HEAVY MINERALS

parting (McBride and Yeakle, 1963) lineations are commonly

present (see Parting Lineations and Current Crescents), giving

the sense of the flow direction but not the absolute direction.

When heavy mineral shadows are present, the asymmetry of

the heavy mineral concentration gradient indicates the

absolute direction, along the lineations (Figure HI).

Rick Cheel

Bibliography

Allen, J.R.L., 1964. Primary current lineations in the Lower Old Red

Sandstone (Devonian), Anglo-Welsh Basin. Sedimentology, 3:

89-108.

Brady, L.L., and Jobson, H.E., 1973. An experimental study of heavy-

mineral segregation under alluvial-flow conditions. US

Geological

Survey Professional

Paper,

562-k, 38pp.

Cheel, R.J., 1984. Heavy mineral shadows: a new sedimentary

structure formed under upper-flow-regime conditions: its direc-

tional and hydraulic significance. Journalof Sedimentary Petrology,

54:

1175-1182.

McBride, E.F., and Yeakel, L.S., 1963. Relationship between parting

lineation and rock fabric. Journal of Sedimentary Petrology, 33:

779-782.

Cross-reference

Parting Lineations and Current Crescents

HEAVY MINERALS

Heavy minerals are high-density components of sihciclastic

sediments. They comprise minerals that have specific gravities

greater than the two main framework components of sands

and sandstones, quartz (s.g. 2.65) and feldspar (s.g. 2.54-2.76).

In practice, heavy minerals are usually considered to be those

with specific gravities greater than 2.8 to 2.9, the limit being

dependent on the density of the liquid used to separate them

from the volumetrically more abundant light minerals. Density

separation is required because heavy minerals rarely comprise

more than 1 percent of sandstones, making it necessary to

concentrate them before analysis can take place. Concentra-

tion is achieved by disaggregation of the sandstone, followed

by mineral separation using dense liquids such as bromoform,

tetrabromoethane or the more recently developed nontoxic

polytungstate liquids. Heavy minerals are generally identified

on the basis of their optical properties under the polarizing

microscope. This is usually achieved using grain mounts but

some workers prefer to use thin sections. Increasingly,

identification is being made on the basis of grain composition,

using microbeam techniques. See Carver (1971) and Mange

and Maurer (1992) for more details on laboratory methods for

the separation and preparation of heavy mineral residues.

Most heavy mineral studies are undertaken to determine

sediment provenance, because heavy mineral suites provide

important information on the mineralogical composition of

source areas (Table HI). Over 50 different non-opaque heavy

mineral species have been recognized in sandstones, many of

which have specific parageneses that enable a direct match

between sediment and source lithology. See Mange and

Maurer (1992) for comprehensive information on the optical

properties and provenance of a large number of non-opaque

heavy minerals.

Geographic and stratigraphic variations in heavy mineral

suites within a sedimentary basin can be used to infer

differences in sediment provenance. Such differences result

either from the interplay between a number of sediment

transport systems draining different source regions, or from

erosional unroofing within a single source area. Heavy mineral

data therefore play an important role in the understanding of

depositional history and paleogeography. In some cases,

sophisticated mathematical and statistical treatment of heavy

mineral data may be required to elucidate the interplay

between multiple sediment transport systems.

Although many heavy mineral species are provenance-

diagnostic, it is rarely possible to directly match heavy mineral

suites in sandstones with those of their source area. This is

because a number of processes have the potential to alter the

original provenance signal at various points in the sedimenta-

tion cycle. The identification of provenance on the basis of

heavy mineral data therefore requires careful consideration of

all the factors that may have influenced the composition of the

assemblages. The factors identified as having significant

potential to overprint the original provenance signal (Morton

and Hallsworth, 1999) are:

• Weathering in the source region: This has the potential to

affect the mineralogy prior to incorporation of sediment in

the transport system, by increasing the relative abundance

of stable to unstable minerals (see Table HI). The effects

of weathering in the source region are unlikely to be

extensive except under transport-limited denudation regimes

(Johnsson

e;a/.,

1991).

• Abrasion during transport: It may cause destruction of

mechanically unstable minerals. Experimental studies have

shown that there are variations in the mechanical stability of

heavy minerals subjected to abrasion. However, the effects

of abrasion on heavy mineral assemblages appear to be

negligible. For example, monazite, determined experimentally

as the least mechanically stable mineral of all, is commonly

found as a placer mineral in beach deposits, even though

beach sediments probably suffer the greatest actual degree

of mechanical abrasion of all environments, with the

possible exception of eolian dune sands.

• Weathering during periods of alluvial storage on the

flood-

plain:

It may cause depletion of chemically unstable

components. There is evidence to suggest this process plays

an important role in modifying sand composition, both in

terms of framework components (Johnsson etal., 1988) and

heavy mineral assemblages (Morton and Johnsson, 1993).

• Hydrodynamics during transport and at the final depositional

site: Since heavy minerals are denser than quartz and

feldspar, their hydrodynamic behavior is different. Further-

more, there is a range of hydrodynamic behavior within the

heavy mineral group owing to the wide range of densities

(Table HI). This is manifested by variations in both settling

velocity and entrainment potential (Rubey, 1933; Slinger-

land, 1977). The variation in hydrodynamic behavior of

heavy minerals is one of the major controls on the relative

abundance of heavy minerals in sands and sandstones.

• Diagenesis: It causes depletion of minerals that are unstable

in the subsurface. Case studies from widely separated

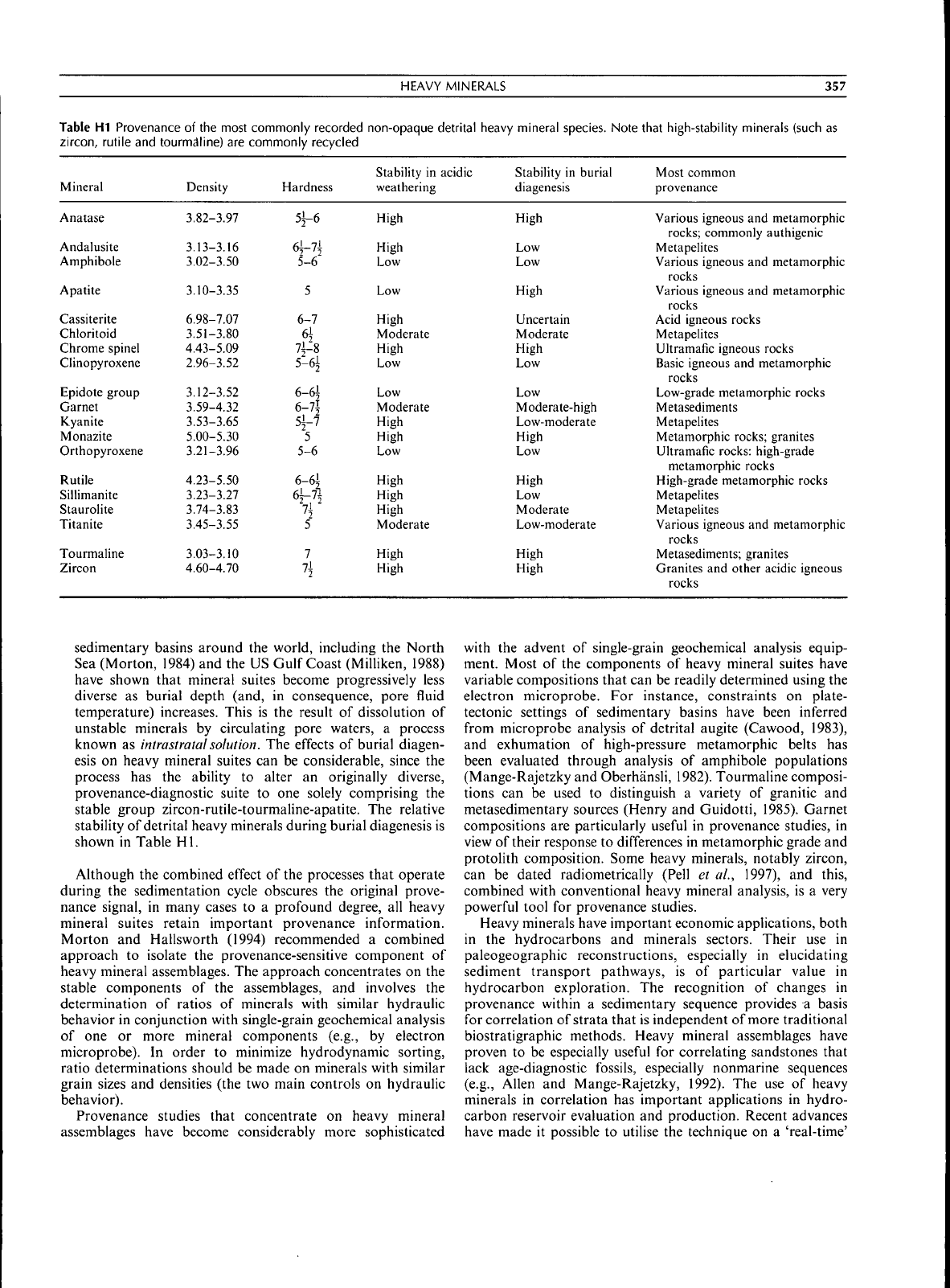

Table HI Provenance of the most

zircon, rutile and

Mineral

Anatase

Andalusite

Amphibole

Apatite

Cassiterite

Chloritoid

Chrome spinel

Clinopyroxene

Epidote group

Garnet

Kyanite

Monazite

Orthopyroxene

Rutile

Sillimanite

Staurolite

Titanite

Tourmaline

Zircon

tourmaline) are

Density

3.82-3.97

3.13-3.16

3.02-3.50

3.10-3.35

6.98-7.07

3.51-3.80

4.43-5.09

2.96-3.52

3.12-3.52

3.59-4.32

3.53-3.65

5.00-5.30

3.21-3.96

4.23-5.50

3.23-3.27

3.74-3.83

3.45-3.55

3.03-3.10

4.60-4.70

commonly recorded

commonly recycled

Hardness

51-6

6i-7i

5-6

5

6-7

71^8

5-6i

6-6i

6-71

5f7

5-6

6-6i

6l-7i

\

1

HEAVY MINERALS

non-opaque detrital heavy

Stability in acidic

weathering

High

High

Low

Low

High

Moderate

High

Low

Low

Moderate

High

High

Low

High

High

High

Moderate

High

High

mineral species. Note

Stability in burial

diagenesis

High

Low

Low

High

Uncertain

Moderate

High

Low

Low

Moderate-high

Low-moderate

High

Low

High

Low

Moderate

Low-moderate

High

High

357

that high-stability minerals (such as

Most common

provenance

Various igneous and metamorphic

rocks;

commonly authigenic

Metapelites

Various igneous and metamorphic

rocks

Various igneous and metamorphic

rocks

Acid igneous rocks

Metapelites

Ultramafic igneous rocks

Basic igneous and metamorphic

rocks

Low-grade metamorphic rocks

Metasediments

Metapelites

Metamorphic rocks; granites

Ultramaflc rocks: high-grade

metamorphic rocks

High-grade metamorphic rocks

Metapelites

Metapelites

Various igneous and metamorphic

rocks

Metasediments; granites

Granites and other acidic igneous

rocks

sedimentary basins around the world, including the North

Sea (Morton, 1984) and the US Gulf Coast (Milliken, 1988)

have shown that mineral suites become progressively less

diverse as burial depth (and, in consequence, pore fluid

temperature) increases. This is the result of dissolution of

unstable minerals by circulating pore waters, a process

known as intrastratalsolution. The effects of burial diagen-

esis on heavy mineral suites can be considerable, since the

process has the ability to alter an originally diverse,

provenance-diagnostic suite to one solely comprising the

stable group zircon-rutile-tourmaline-apatite. The relative

stability of detrital heavy minerals during burial diagenesis is

shown in Table HI.

Although the combined effect of the processes that operate

during the sedimentation cycle obscures the original prove-

nance signal, in many cases to a profound degree, all heavy

mineral suites retain important provenance information.

Morton and Hallsworth (1994) recommended a combined

approach to isolate the provenance-sensitive component of

heavy mineral assemblages. The approach concentrates on the

stable components of the assemblages, and involves the

determination of ratios of minerals with similar hydraulic

behavior in conjunction with single-grain geochemical analysis

of one or more mineral components (e.g., by electron

microprobe). In order to minimize hydrodynamic sorting,

ratio determinations should be made on minerals with similar

grain sizes and densities (the two main controls on hydraulic

behavior).

Provenance studies that concentrate on heavy mineral

assemblages have become considerably more sophisticated

with the advent of single-grain geochemical analysis equip-

ment. Most of the components of heavy mineral suites have

variable compositions that can be readily determined using the

electron microprobe. For instance, constraints on plate-

tectonic settings of sedimentary basins have been inferred

from microprobe analysis of detrital augite (Cawood, 1983),

and exhumation of high-pressure metamorphic belts has

been evaluated through analysis of amphibole populations

(Mange-Rajetzky and Oberhansli, 1982). Tourmaline composi-

tions can be used to distinguish a variety of granitic and

metasedimentary sources (Henry and Guidotti, 1985). Garnet

compositions are particularly useful in provenance studies, in

view of their response to differences in metamorphic grade and

protolith composition. Some heavy minerals, notably zircon,

can be dated radiometdcally (Pell et al., 1997), and this,

combined with conventional heavy mineral analysis, is a very

powerful tool for provenance studies.

Heavy minerals have important economic applications, both

in the hydrocarbons and minerals sectors. Their use in

paleogeographic reconstructions, especially in elucidating

sediment transport pathways, is of particular value in

hydrocarbon exploration. The recognition of changes in

provenance within a sedimentary sequence provides a basis

for correlation of strata that is independent of more traditional

biostratigraphic methods. Heavy mineral assemblages have

proven to be especially useful for correlating sandstones that

lack age-diagnostic fossils, especially nonmarine sequences

(e.g., Allen and Mange-Rajetzky, 1992). The use of heavy

minerals in correlation has important applications in hydro-

carbon reservoir evaluation and production. Recent advances

have made it possible to utilise the technique on a 'real-time'

358

HINDERED SETTLING

basis at the well site, where it is used to help steer high-angle

wells within the most productive reservoir horizons (Morton

etal., in press).

Heavy minerals may become concentrated naturally by

hydrodynamic sorting, usually in shallow marine or fluvial

depositional settings. Naturally occurring concentrates of

economically valuable minerals are known as placers

(q.v.),

and such deposits have considerable commercial significance.

Cassiterite, gold, diamonds, chromite, monazite and rutile are

among the minerals that are widely exploited from placer

deposits.

Andrew C. Morton

Bibliography

Allen, P.A., and Mange-Rajetzky, M.A., 1992. Devonian-Carbonifer-

ous sedimentary evolution of the Clair Area, offshore northwestern

UK: impact of changing provenance. Marineand PetroleumGeology,

9: 29-52.

Carver, R.E., 1971. Heavy mineral separation. In Carver, R.E. (ed.).

Procedures in Sedimentary Petrology. New York: Wiley, pp.

427-452.

Cawood, P.A., 1983. Modal composition and detrital clinopyroxene

geochemistry of lithic sandstones from the New England fold belt

(east Australia): a Paleozoic forearc terrain. Bulletin of the

Geologi-

cal Society of America, 94: 1199-1214.

Henry, D.J., and Guidotti, C.V., 1985. Tourmaline as a petrogenetic

indicator mineral: an example from the staurolite-grade metapelites

of NW Maine. American Mineralogist, 70: 1-15.

Johnsson, M.J., Stallard, R.F., and Lundberg, N., 1991. Controls on

the composition of fluvial sands from a tropical weathering

environment: sands of the Orinoco drainage basin, Venezuela

and Colombia. Bulletin of

the

Geological Society of America, 103:

1622-1647.

Johnsson, M.J., Stallard, R.F., and Meade, R.H., 1988. First-cycle

quartz arenites in the Orinoco River Basin, Venezuela and

Colombia. Journal of Geology, 96: 103-277.

Mange, M.A., and Maurer, H.F.W., 1992. Heavy Minerals in Colour.

London: Chapman and Hall.

Mange-Rajetzky, M.A., and Oberhansli, R., 1982. Detrital lawsonite

and blue sodic amphibole in the Molasse of Savoy, France and

their significance in assessing Alpine evolution. Schweizerisclie

Mineralogischeund

Petrographische

Mitteilungen, 62: 415-436.

Milliken, K.L., 1988. Loss of provenance information through

subsurface diagenesis in Plio-Pleistocene sediments, northern Gulf

of Mexico. Journalof Sedimentary

Petrology,

58: 992-1002.

Morton, A.C., 1984. Stability of detrital heavy minerals in Tertiary

sandstones of the North Sea Basin. Clay Minerals, 19: 287-308.

Morton, A.C., and Hallsworth, C.R., 1994. Identifying provenance-

specific features of detrital heavy mineral assemblages in sand-

stones. Sedimentary Geology, 90: 241-256.

Morton, A.C., and Hallsworth, C.R., 1999. Processes controlling the

composition of heavy mineral assemblages in sandstones. Sedi-

mentary Geology, 124: 3-29.

Morton, A.C., and Johnsson, M.J., 1993. Factors influencing the

composition of detrital heavy mineral suites in Holocene sands of

the Apure river drainage basin, Venezuela. In Johnsson, M.J., and

Basu, A. (eds.). Processes Controlling the Composition of Clastic

Sediments. Geological Society of America, Special Paper, 284,

171-185.

Morton, A.C., Spicer, P.J., and Ewen, D.F., in press. Geosteering of

high-angle wells using heavy mineral analysis: the Clair Field, West

of Shetland. In Carr, T., Feazel, C, Mason, E., and Sorensen, R.

(eds.).

Horizontal Wells, Focus on the Reservoir. Memoir of the

American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

Pell, S.D., Williams, I.S., and Chivas, A.R., 1997. The use of protolith

zircon-age fingerprints in determining the protosource areas for

some Australian dune sands. Sedimentary Geology, 109: 233-260.

Rubey, W.W., 1933. The size distribution of heavy minerals within a

water-lain sandstone. Journalof Sedimentary

Petrology,

3: 3-29.

Slingerland, R.L., 1977. The effect of entrainment on the hydraulic

equivalence relationships of light and heavy minerals in sands.

Journal of Sedimentary

Petrology,

47: lii-llQ.

Cross-references

Attrition (Abrasion), Fluvial

Grain Settling

Grain Threshold

Placers

Provenance

HINDERED SETTLING

Gravitational segregation and settling of particles in an

aqueous suspension are strongly affected by suspension

concentration. Lone particles or particles in very low-

concentration suspensions settle freely through a fluid un-

encumbered by hydrodynamic influences of other particles (see

Grain

Settling). However, at a sufficient volume concentration

of solids, changes in fluid density and viscosity, particle

interactions, and upwelling of fluid caused by downward

particle motion (Hawksley, 1951; Davies, 1968) hinder particle

settling. As a result, enhanced particle segregation occurs and

overall particle-settling velocity is less than that of a single

particle of the same size settling in an infinite fluid.

For nearly a century scientists have recognized that particle

concentration affects the physical properties of fluids and

particle settling behavior. Sedimentation of any given particle

in a suspension is affected by both the mere presence of other

particles as well as by motion of neighboring particles. The

presence of rigid particles in a fluid distorts fluid motion as the

fluid is at rest at particle surfaces. Such distortion leads to an

increase in effective fluid viscosity, which is reasonably

predictable for dilute (<10 percent solids volume) suspensions

(Einstein, 1906). Particle motion also distorts fluid motion by

dragging fluid along as particles settle. However, owing to

mass conservation, downward particle motion induces fluid

upwelling which can enhance particle buoyancy and help

hinder particle settling.

Over the past several decades, various models have been

proposed to predict sedimentation velocities of different

particle species in suspensions. Each of these models defines

a so-called hindered settling function that describes the

reduction of particle settling velocity as a function of particle

concentration (e.g., Richardson and Zaki, 1954; Davis and

Gecol, 1994). Efforts have evolved from modeling suspensions

of monosized spheres at low Reynolds number (Re<0.5) to

multicomponent (i.e., multiple grain size and density) suspen-

sions at finite (1-100) Reynolds numbers (Davis and Gecol,

1994;

Manasseh et al., 1999), and toward development of

numerical models that simulate deposition from multicom-

ponent suspensions containing large numbers of particles (e.g.,

Zeng and Lowe, 1992; Hofler etal., 2000).

The following discussion outlines the effects of solids

concentration on particle settling and the effects of particle

settling behavior on the character of resulting sedimentary

deposits. The discussion focuses on the behavior of non-

flocculating suspensions in static fluids. Flocculent suspensions

HINDERED SETTLING

359

t

o

O

/

1

V

o

o

Q

° o

)

; °

g

z'

•

i

V

Moderate

1

a

o

) t

0

Oc

7

Concentration

. ^^ o

High

Concentration

O

Low

Concentration

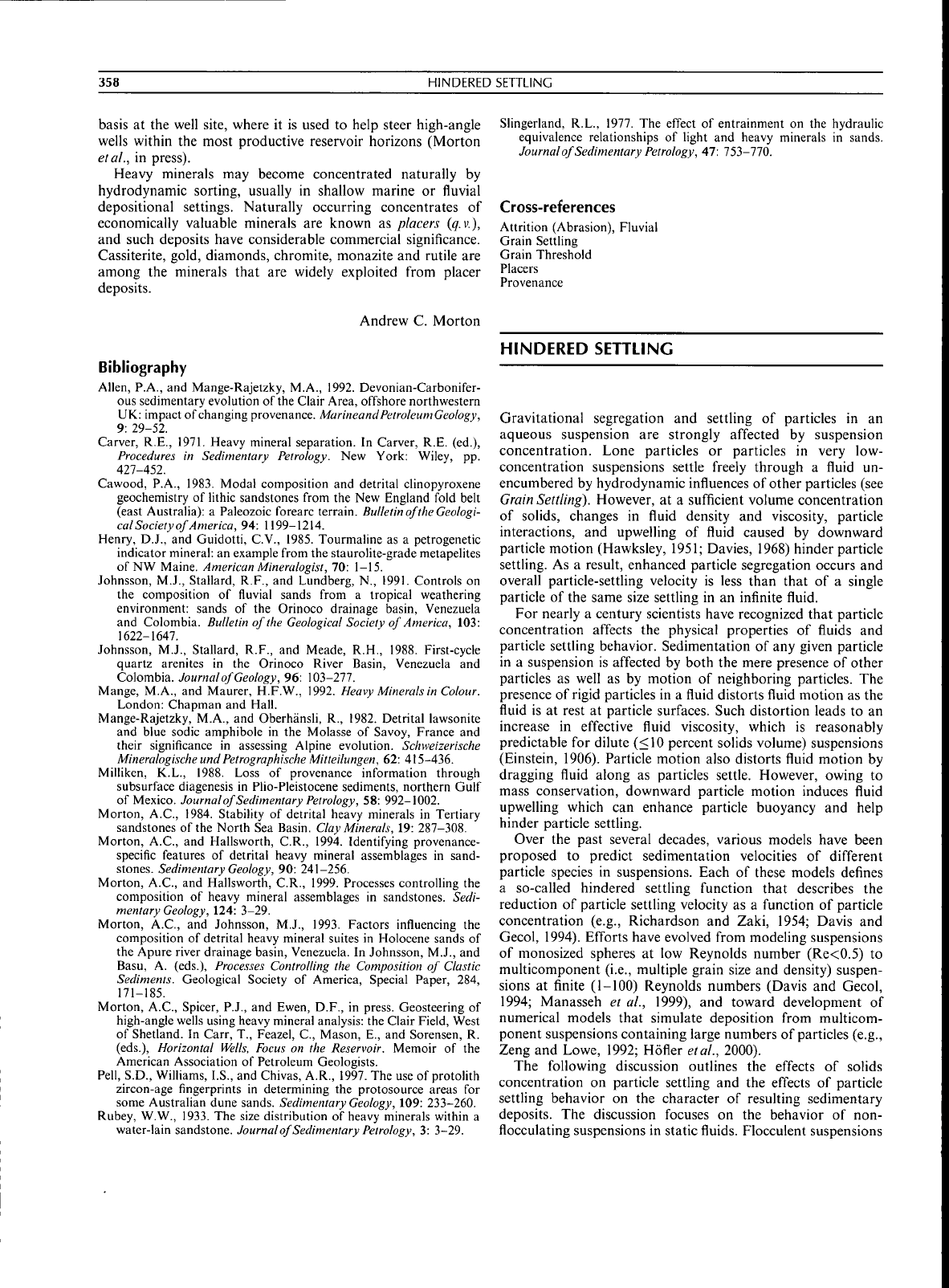

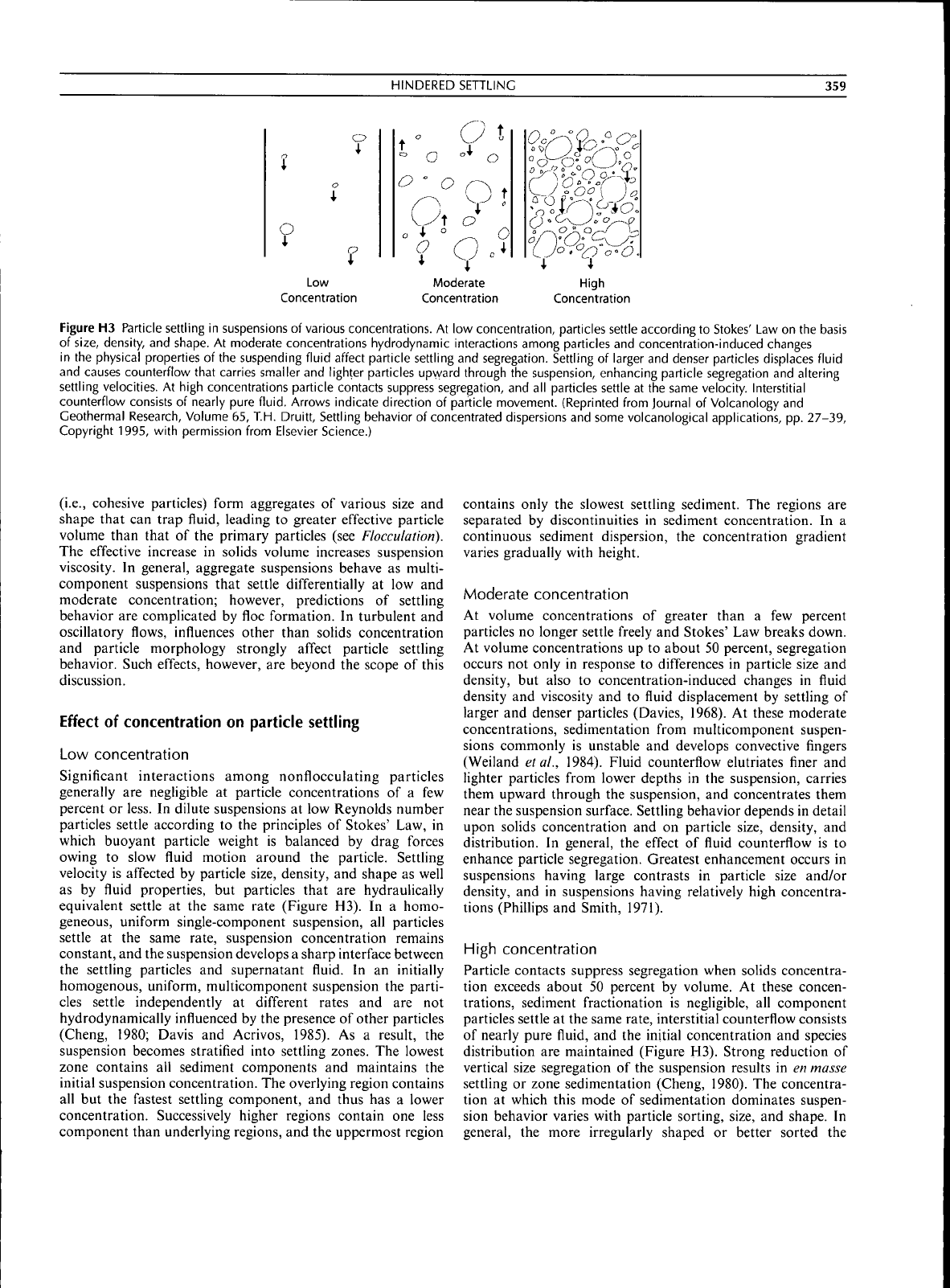

Figure H3 Particle settling in suspensions of various concentrations. At low concentration, particles settle according to Stokes' Law on the basis

of size, density, and shape. At moderate concentrations hydrodynamic interactions among particles and concentration-induced changes

in the physical properties of the suspending fluid affect particle settling and segregation. Settling of larger and denser particles displaces fluid

and causes counterflow that carries smaller and lighter particles upvvard through the suspension, enhancing particle segregation and altering

settling velocities. At high concentrations particle contacts suppress segregation, and all particles settle at the same velocity. Interstitial

counterflow consists of nearly pure

fluid.

Arrows indicate direction of particle movement. (Reprinted from Journal of Volcanology and

Ceothermal Research, Volume 65, T.H. Druitt, Settling behavior of concentrated dispersions and some volcanological applications, pp. 27-39,

Copyright 1995, with permission from Elsevier Science.)

(i.e.,

cohesive particles) form aggregates of various size and

shape that can trap fluid, leading to greater effective particle

volume than that of the primary particles (see Flocculaiion).

The effective increase in solids volume increases suspension

viscosity. In general, aggregate suspensions behave as multi-

component suspensions that settle differentially at low and

moderate concentration; however, predictions of settling

behavior are complicated by floe formation. In turbulent and

oscillatory flows, influences other than solids concentration

and particle morphology strongly affect particle settling

behavior. Such effects, however, are beyond the scope of this

discussion.

Effect of concentration on particle settling

Low concentration

Significant interactions among nonfiocculating particles

generally are negligible at particle concentrations of a few

percent or less. In dilute suspensions at low Reynolds number

particles settle according to the principles of Stokes' Law, in

which buoyant particle weight is balanced by drag forces

owing to slow fluid motion around the particle. Settling

velocity is affected by particle size, density, and shape as well

as by fluid properties, but particles that are hydraulieally

equivalent settle at the same rate (Figure H3). In a homo-

geneous, uniform single-component suspension, all particles

settle at the same rate, suspension concentration remains

constant, and the suspension develops a sharp interface between

the settling particles and supernatant fluid. In an initially

homogenous, uniform, multicomponent suspension the parti-

cles settle independently at different rates and are not

hydrodynamically influenced by the presence of other particles

(Cheng, 1980; Davis and Aerivos, 1985). As a result, the

suspension becomes stratified into settling zones. The lowest

zone contains all sediment components and maintains the

initial suspension concentration. The overlying region contains

all but the fastest settling component, and thus has a lower

concentration. Successively higher regions contain one less

component than underlying regions, and the uppermost region

contains only the slowest settling sediment. The regions are

separated by discontinuities in sediment concentration. In a

continuous sediment dispersion, the concentration gradient

varies gradually with height.

Moderate concentration

At volume concentrations of greater than a few percent

particles no longer settle freely and Stokes' Law breaks down.

At volume concentrations up to about 50 percent, segregation

occurs not only in response to differences in particle size and

density, but also to concentration-induced changes in fluid

density and viscosity and to fluid displacement by settling of

larger and denser particles (Davies, 1968). At these moderate

concentrations, sedimentation from multicomponent suspen-

sions commonly is unstable and develops convective fingers

(Weiland etal., 1984). Fluid counterflow elutriates finer and

lighter particles from lower depths in the suspension, carries

them upward through the suspension, and concentrates them

near the suspension surface. Settling behavior depends in detail

upon solids concentration and on particle size, density, and

distribution. In general, the effect of fluid counterflow is to

enhance particle segregation. Greatest enhancement occurs in

suspensions having large contrasts in particle size and/or

density, and in suspensions having relatively high concentra-

tions (Phillips and Smith, 1971).

High concentration

Particle contacts suppress segregation when solids concentra-

tion exceeds about 50 percent by volume. At these concen-

trations, sediment fractionation is negligible, all component

particles settle at the same rate, interstitial counterflow consists

of nearly pure fluid, and the initial concentration and species

distribution are maintained (Figure H3). Strong reduction of

vertical size segregation of the suspension results in en masse

settling or zone sedimentation (Cheng, 1980). The concentra-

tion at which this mode of sedimentation dominates suspen-

sion behavior varies with particle sorting, size, and shape. In

general, the more irregularly shaped or better sorted the

360

HINDERED SETTLING

sediment components, the lower the concentrations at which

this mode of sedimentation occurs (Davies, t968).

Effects of suspension concentration and settling

behavior on deposit character

Experiments by Druitt (1995) illustrate several aspects of

settling behaviors of variably concentrated, multicomponent

suspensions on deposit character. The experiments consisted of

poorly sorted mixtures of variable size and density plastic and

silicon carbide particles having total solids concentrations

ranging from 10 percent to 60 percent by volume.

Low-concentration suspension

Despite violating the general conditions for free settling, a

10 percent concentration mixture generally settled as a typical

low-concentration suspension. The densest particles segregated

rapidly according to particle size and produced a normally

graded deposit devoid of sedimentary structures. The lighter,

but larger, plastic particles settled with their hydraulieally

equivalent silicon carbide counterparts, and were dispersed

through the deposit according to their hydraulic equivalence.

If settling was at all hindered by hydrodynamic particle

interactions at this concentration, sueh hinderance was not

readily apparent in the resulting deposit.

Moderate-concentration suspension

Hindered settling affected the sedimentologie characteristics of

deposits from suspensions having concentrations ranging from

25 percent to 55 percent. Initially well dispersed suspensions

segregated rapidly according to partiele size and density, and

formed suspensions having vertical concentration gradients.

Settling of the dense silicon carbide particles generated

vigorous upwelling that swept the finest and lightest particles

upward through the suspensions. The light plastic particles

segregated and rose upward to their levels of neutral buoyancy

(near the surface in the more concentrated suspensions), and at

the tops of the suspensions zones of fine particles developed

that thickened with time.

Sedimentation by these suspensions produced normally

graded deposits having elutriation pipes (finger-like zones of

well sorted sediment resulting from upward fluid flow),

"floating" rafts of light particles, and capping layers of fines

elutriated by escaping pore fluid.

Higb-concentration suspension

A 60 percent concentration mixture settled as a typical high-

concentration suspension. There was little contrast between

the sedimentologic character of the suspension and its resulting

deposit. Minor segregation of particles of different sizes or

densities occurred, escaping fluid focused along discrete, high-

permeability zones, and the suspension dewatered and

consolidated upward from the deposit base (e.g.. Major,

2000).

The resulting deposit was poorly sorted and ungraded,

and was capped by a very thin layer of elutriated fines.

Summary

The settling behavior of suspensions of nonfloeculating solids

is strongly affected by solids concentration in addition to

particle size, shape, and density. Particles segregate and settle

according to size and density at low concentrations. At higher

concentrations, particle segregation and settling are modified

by changes in fluid properties wrought by inereased particle

volume, by hydrodynamic interactions among particles, and

by fluid displacement and counterflow, which can greatly

enhance size and density segregation. At sufficiently high

concentrations, particle segregation is suppressed resulting in

en masse settling of the entire suspension.

Jon J. Major

Bibliography

Cheng, D.C.-H., 1980. Sedimentation of suspensions and storage

stability. Chemistry and Industry, 10: 407-414.

Davies, R., 1968. The experimental study of the differential settling of

particles in suspensions at high concentrations.

Powder

Technology,

2:43-51.

Davis,

R.H., and Aerivos, A., 1985. Sedimentation of noncolloidal

particles at low Reynolds numbers. Annual Reviews of Fluid

Mechanics, 17: 91-118.

Davis,

R.H., and Gecol, H., 1994. Hindered settling function with no

empirical parameters for polydisperse suspensions. American Insti-

tute of Chemical Engineers Journal, 40: 570-575.

Druitt, T.H., 1995. Settling behaviour of concentrated dispersions

and some volcanological applications. Journal of

Volcanology

and

Geothermal Research, 65: 27-39.

Einstein, A., 1906. Eine neue Bestimmung der Molekuldimensions.

Annalen der Physik, 19: 289-306.

Hawksley, P.G., 1951. The effect of concentration on the settling of

suspensions and flow through porous media. In Some Aspects of

Fluid

Flow.

London: Edward Arnold and Co., pp. 114-135.

Hofler, K., Muiler, M., and Sehwarzer, S., 2000. Design and

application of object oriented parallel data structures in particle

and continuous systems. In Krause, E., and Jager, W. (eds.). High

Performance Computing in Science and Engineering '99. Berlin:

Springer, pp. 403-412.

Major, J.J., 2000. Gravity-driven consolidation of granular slurries:

implications for debris-flow deposition and deposit characteristics.

Journalof Sedimentary Research, 70:

64-83.

Manasseh, R., Metcalfe, G., and Wu, J., 1999. Polydisperse

sedimentation processes: macro- and micro-scale experiments. In

Celata, G.P., DiMareo, P., and Shah, R.K. (eds.). Two-phase

Flow Modelling and Experimentation 1999. Pisa: Edizioni ETS,

pp.

881-888.

Phillips, C.R., and Smith, T.N., 1971. Modes of settling and relative

settling velocities in two-species dispersions. Industrial and Engi-

neering Chemistry Fundamentals, 10: 581-587.

Riehardson, J.F., and Zaki, W.N., 1954. Sedimentation and fluidisa-

tion: part I. Transaclionsofthe Institutionof Chemical Engineers, 32:

35-53.

Weiland, R.H., Fessas, Y.P., and Ramarao, B.V., 1984. On

instabilities arising during sedimentation of two-component

mixtures of solids. Journal of Fluid Mechanics, 142: 383-389.

Zeng, J., and Lowe, D.R., 1992. A numerieal model for sedimentation

from highly-eoncentrated multi-sized suspensions. Mathematical

Geology, 24: 393-415.

Cross-references

Fabric, Porosity, and Permeability

Flocculation

Grading, Graded Bedding

Grain Settling

Grain Size and Shape

Gravity-Driven Mass Flows

Liquefaction and Fluidization

Slurry

HUMIC SUBSTANCES IN SEDIMENTS

361

HUMIC SUBSTANCES IN SEDIMENTS

Introduction

Organic carbon compounds are a ubiquitous and essential

constituent in sedimentary systems. They fuel virtually all

biogeochemical cycles, and are important reservoirs for the

major elements of living systems: carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen,

oxygen, phosphorous, and sulfur. The physiology of living

organisms combined with physicochemical transformations

occurring during sediment burial and lithification imparts

compositional, structural and isotopic characteristics to

organic matter that serve as an important facet of the

sedimentary record. Humic substances are high-molecular

weight organic compounds defined operationally on the basis

of solubility properties and high molecular weight (hundreds

to 300,000 Da). They comprise a significant fraction (up to

70-80 percent) of organic matter in soils and recent sediments,

and represent a complex organic mixture of primary biochem-

ical compounds and their by-products formed by microbial

degradation, oxidation, and incipient chemical polymerization/

condensation. Continued thermal exposure and time result in

more extensive chemical modification including the formation

of kerogen and coal, as well as the release of organic acids,

hydrocarbons, and carbon dioxide.

History and importance

Humic substances (HS) have had a long history of examina-

tion (compilations include Schnitzer and Khan, 1972;

Gjessing, 1976; Christman and Gjessing, 1983; Aiken etal.,

1985;

and Thurman, 1985). Since the late 1700s, workers have

focused on the important role of humic substances in soils and

agriculture. Stevenson (1985) provides a detailed history of the

study of humic substances. Since 1970, advances in analytical

techniques in organic chemistry and petroleum-related re-

search resulted in great advances in understanding sedimentary

organic matter as the precursor to kerogen {q.v., and see

Durand, 1980). In the 1980s and beyond, interest in HS

expanded within ecology and environmental sciences. Many of

these advances were related to efforts to better characterize HS

(a major fraction of dissolved organic carbon) in a variety of

aquatic environments, including groundwater systems (Aiken

et al., 1985). Now, at the turn of the millennium, the

importance of humic substances in global earth systems and

biogeochemical cycling continues to be a growing field.

Biomedical technology has led to powerful new methods of

analyzing important biomolecules such as DNA, which may

be applied to HS. Yet even as analytical capabilities continue

to better resolve the individual components of HS, the most

fundamental questions are currently being revisited: what are

humic substances? Are the traditional concepts of humic

substances appropriate (Tate, 2001; Burdon, 2001)? And

important new questions may be answerable: how does organic

carbon sequestration in soils affect atmospheric CO2? In

what ways can/do humic substances attenuate the migration

and bioavailability of anthropogenic organic chemicals and

metals?

Composition

Humic substances are complex mixtures of organic com-

pounds. They are operationally defined on the basis of

solubility. Humic substances are separated by soil or sediment

extraction into humic acid (soluble in aqueous media at

pH > 2), fulvic acid (soluble in aqueous media across the range

of pH) and humin (insoluble in aqueous media). In tJie

traditional view, HS are mixtures of plant and microbial

carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids, with degraded lignins and

tannins combined in high molecular weight "polymers"

through hydrophobic (e.g., van der Waals) and hydrogen

bonds. Although each HS "molecule" is essentially unique,

generalized formulas are based on average composition (C, H,

N,

S, and O content and proportions of various organic

functional groups). Table H2 presents average elemental

compositional ranges for humic and fulvic acids. Variations

in initial organic matter composition, the availability of water

and presence of oxygen all play a role in the transformation of

labile biogenic compounds into HS.

Structure

Structural determinations of HS have historically been

performed on HS after separation by a variety of isolation

and fractionation procedures. Isolation generally involves

extraction by use of sodium pyrophosphate or other solvents

buffered over several pH ranges. Fractionation has been

performed by use of resin columns (singly or in tandem), and

more recently, through use of gel filtration techniques. Hayes

and Malcolm (2001) summarize these procedures. Hatcher and

others (2001) provide a thorough overview of structural

determinations based on a variety of methods, including

pyrolysis coupled with gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

(GC-MS). The basic structure for a "typical" humic acid

molecule consists of aromatic rings bridged by a variety of

CH2,

N, S, and O groups, with peripherally attached protein

and carbohydrate residues and simple carboxyl and phenolic

moieties. Reconstructions of high-molecular weight substances

consistent with observed products and considering the

degradation associated with extraction and fractionation

procedures has led to the conventional mega-structures

thought to exist. Piccolo (2001) takes issue with these

constructs and argues for an interpretation of simpler (and

smaller) naturally occurring molecules. Advanced techniques

in solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR; Hatcher

et al., 2001) which look directly at untreated organic struc-

tures,

hold great promise for unraveling of these difficulties.

Additional tools developed for biomolecular analysis with

applications to HS include electrospray ionization and matrix-

assisted laser desorption ionization (Hatcher et al., 2001).

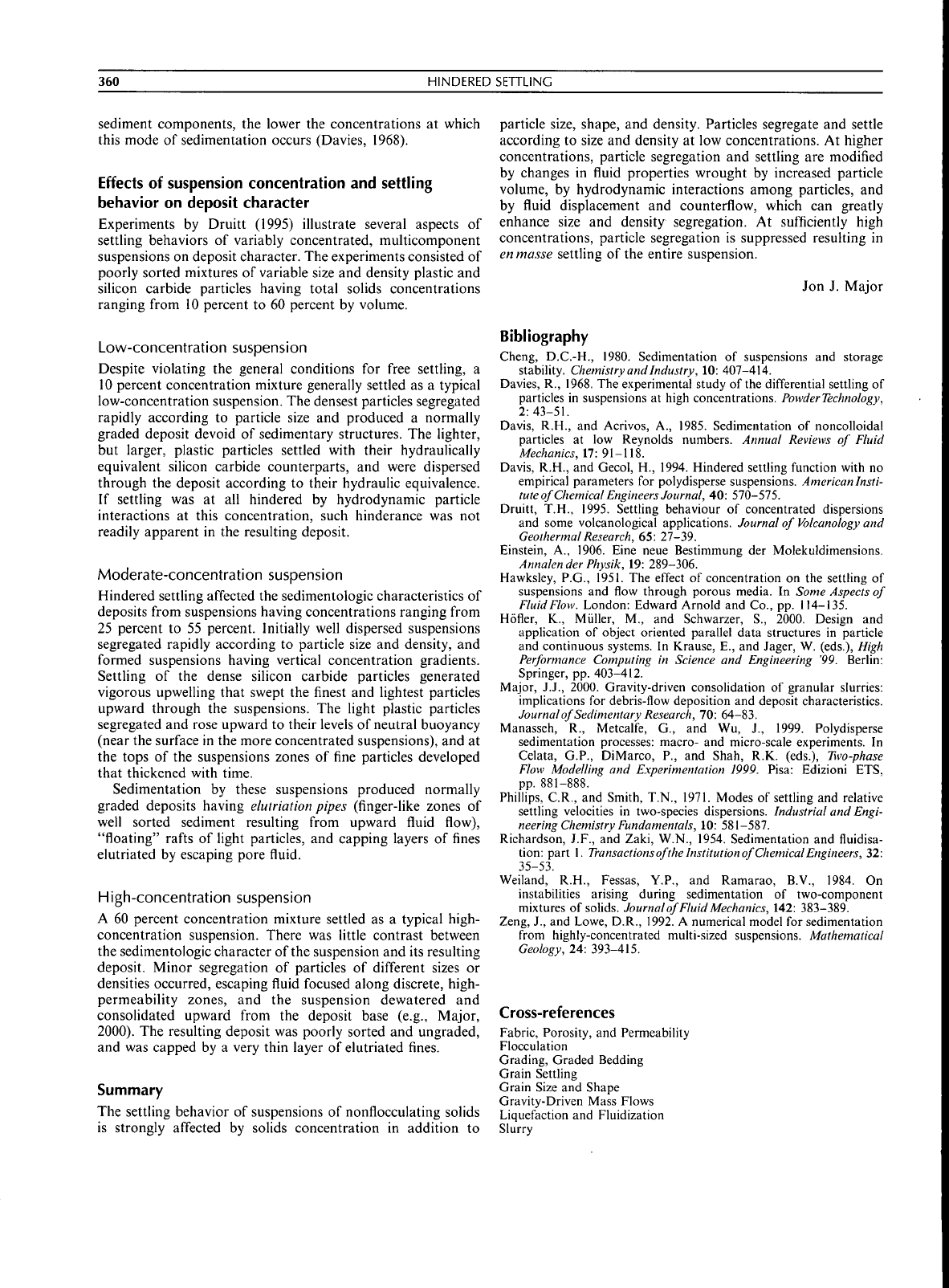

Table H2 Average Values of Elemental Compositions of Humic

Substances

Humic acid Fulvic acid

Carbon

Hydrogen

Oxygen

Nitrogen

Sulfur

from Steelink (1985).

53.8-58.7%

3.2-6.2

32.8-38.3

0.8-4.3

0.1-1.5

40.7-50.6%

3.8-7.0

39.7-49.8

0.9-3.3

0.1-3.6

362 HUMMOCKY AND SWALEY CROSS-STRATIFICATION

Despite advances in analytical methodology, often the

characterized component of humic substances remains at only

20 percent.

Diagenesis

Humic substances are a transitional form of organic com-

pounds between biomolecules and important fossil fuels

(kerogen, coal, oil, and gas). Systematic changes in both

structure and composition result as sediments undergo

diagenesis and lithification during burial.

Terrestrial sediments

Terrestrial environments with significant components of humic

substances include soils, peatlands, lakes, streams, and

groundwater. Humic substances differ across these environ-

ments based on initial type of organic matter, subsequent

exposure to organic matter recycling, and the extent of

subsurface oxidation. Lakes sediments dominated by algal

organic matter have higher than average H/C ratios do to the

high proportion of sugars, carbohydrates and lipids as

compared to greater oxygen content of cellulose and lignin-

derived organic matter. Continued burial of terrestrial humic

substances rich in oxygen (cellulose and lignin derivatives)

leads to the formation of peat and eventually coal. The

sapropel (algal-dominated) deposits of saline lakes eventually

yield hydrocarbons due to the high H/C mentioned above.

Christman, R.F., and Gjessing, E.T. (eds.), 1983. Aquatic and

Terrestrial Humie Materials. Ann Arbor: Ann Arbor Science

Publications.

Durand, B., 1980. Kerogen—Insoluble

Organic

Matter from Sedimentary

Rocks. Paris: Editions Technip.

Engel, M.H., and Macko, S.A. (eds.), 1993. Organic Geochemistry:

Principles

and Applications. New York: Plenum Press.

Gjessing, 1976. Physical and Chemical Characteristics of Aquatic

Humus. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Ann Arbor Science.

Hatcher, P., Dria, K., Kim, S., and Frazier, S., 2001. Modern

analytical studies of humic substances. Soil Science, 166: 770-794.

Hayes, M., and Malcolm, R., 2001. Structures of humic substances. In

Clapp, C, Hayes, M., Senesi, N., Bloom, P., and Jardine, P. (eds.),

Humic Substances and Chemical Contaminants. WI: Soil Science

Society of America, pp. 3-40.

Piccolo, A., 2001. The supramolecular structure of humic substances.

Soil Science, 166: 810-832.

Schnitzer, M., and Khan, S.U. (eds.), 1972. Humic Substances in the

Environment. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Steelink, C, 1985. Implications of elemental characteristics of humic

substances. In Aiken, G., McKnight, D., Wershaw, R., and

MacCarthy, P. (eds.), Humic Substances

in

Soil, Sediment andWaier.

New York: Wiley Interscienee, pp. 457-476.

Stevenson, F.J., 1985. Geochemistry of soil humic substances. In

Aiken, G.R., McKnight, D.M., Wershaw, R.L., and MacCarthy,

P.

(eds.), Humic Substances

in

Soil, Sediment and

Water.

New York:

Wiley Interscienee.

Tate,

R., 2001. Soil organic matter: evolving concepts. Soil Science,

166:

721-722.

Thurman, E.M., 1985. Organic Geochemistry of Natural Waters.

Dordrecht, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhoff/Dr. W. Junk

Publishers.

Marine sediments

Humic substances in marine sediments derive from both

degraded terrestrial organic matter and marine sources. Fulvic

acid contents decrease with increasing burial depth in marine

sediments. In the humic acid fraction, O/C and N/C ratios also

decrease with burial. It is probable that fulvic acid is a product

of oxidation of organic matter, and that its production

decreases with depth due to a decrease in oxygen availability.

Fulvic acid also decreases due to solubilization in the aqueous

media and consumption by microbial populations. Humic acid

becomes progressively less soluble with depth due to con-

densation reactions forming humin and eventually kerogen.

Summary

Humic substances in soils and sediment constitute a significant

and dynamic reservoir of organic carbon, essential for

considerations of carbon cycling. They are also critical in

consideration of metal mobility and bioavailability due to

metal binding capacities of immobile humic substances and the

complexation stability of labile aqueous humic acids. Despite

their study for more than two centuries, major advances in

understanding HS with applications to agriculture, environ-

mental change, and the energy industry await further

investigation.

Laura J. Crossey

Bibliography

Aiken, G.R., McKnight, D.M., Wershaw, R.L., and MacCarthy, P.

(eds.),

1985. Humic Substances in Soil, Sediment and Water.

New York: Wiley Interscienee.

Burden, J., 2001. Are the traditional concepts of the structures of

humic substances realistic? Soil Science, 166: 752-769.

HUMMOCKY AND SWALEY CROSS-

STRATIFICATION

Hummocky and swaley cross-stratification are two closely

related forms of stratification that are generally attributed to

the action of oscillating (wave-generated) currents or combined

(oscillating and unidirectional) fiows. While these structures

were once thought to be ubiquitous to shallow marine storm

deposits, similar forms of stratification have been recognized in

both clastic and carbonate sediments of a variety of deposi-

tional environments.

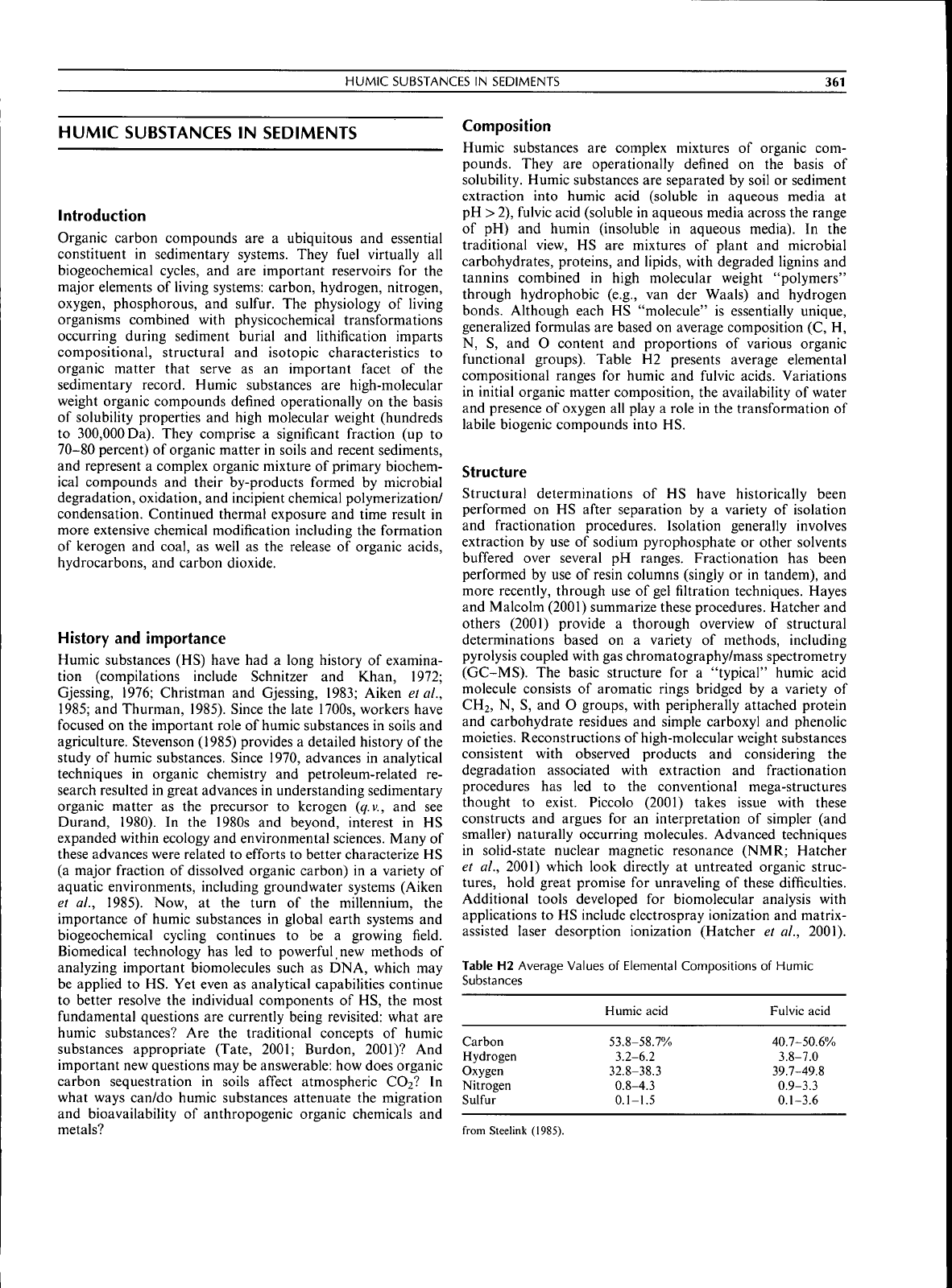

Hummocky cross-stratification (HCS) was first described by

that name by Harms etal. (1975) although the structure had

been described in earlier literature by other names (e.g.,

"truncated wave ripple laminae", Campbell, 1966; "crazy

bedding", Howard, 1971; "truncated megaripples", Howard,

1972).

This structure is characterized by internal laminae that

locally dome upward (hummocks) passing laterally into

laminae that are concave upward (swales) as shown in

Figure H4. HCS is generally thought to be limited to coarse

silt and fine sand (Dott and Bourgeois, 1982; Brenchley, 1985;

Swift etal., 1987) although it is rarely reported in coarse sand

(e.g., Brenchley and Newall, 1982). The fundamental char-

acteristics of HCS were listed by Harms etal. (1982, pp. 3-30)

and remain important for the recognition of this structure:

"(1) lower bounding surfaces of sets are erosional and

commonly slope at angles less than 10°, though dips can

reach 15°; (2) laminae above these erosional set boundaries are

parallel to that surface, or nearly so; (3) laminae can

systematically thicken laterally in a set, so that their traces

on a vertical sequence are fan-like and dip diminishes

HUMMOCKY AND SWALEY CROSS-STRAT1FK"ATK)N

regularly: and (4) dip directions of erosional set boundaries

and of the overlying laminae are scattered."" Harms et ai

{1982)

further stated that the scale of the stratifieation varies

from medium to large scale (decimeters to meters from

lumimock crest to hummock crest). They attributed the form

of the stratilication to deposition o\\ bedfortiis that consisted

of, more or less, circular hummocks (positive topographic

features) and swales (negative topographic features): thus, the

form of the stratification mimics the morphology of the

bcdform.

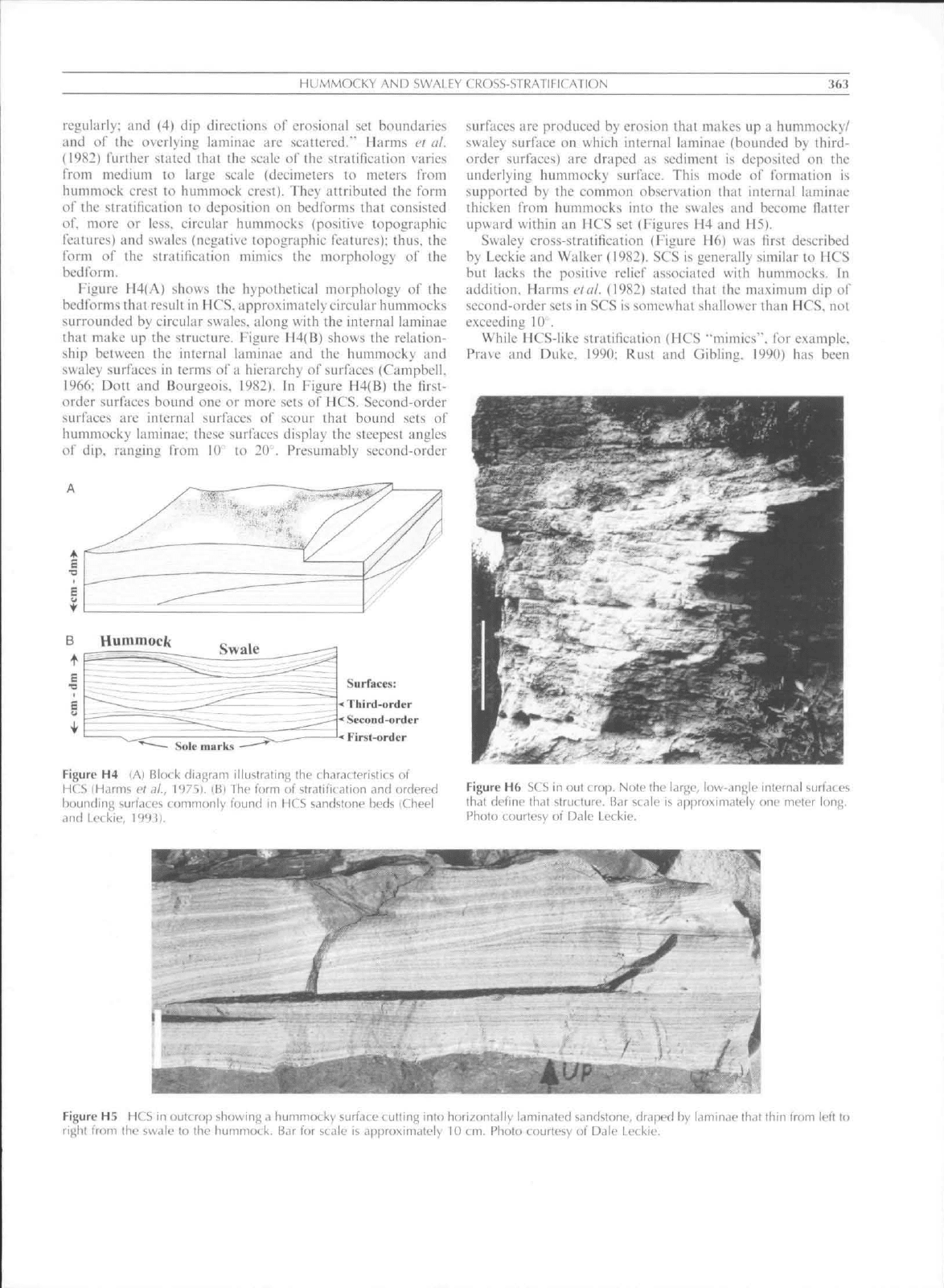

Figure H4(A) shows the hypothetical morphology of the

bcdforms that result in HCS. approximately circular hutntnocks

surrounded by circular swales, along with the intcinal laminae

that make up the structure. Figure H4(B) shows the relation-

ship between the internal laminae and the hummocky and

swaley surfaces in terms of a hierarchy of surfaces (Campbell.

1966;

Dott and Bourgeois, 1982). In Figure H4(B) the first-

order surfaces bound one or more sets of HCS. Second-order

surfaces are internal surfaces of scour that bound sets of

hummocky laminae; these surfaces display the steepest angles

of dip, ranging from 10' to 20^ Presumably second-order

B Hummock

Swale

Sole marks

Surfaces:

Third-order

•<

Second-order

First-order

Figure H4 lA) Block diajjram illustrating the characteristics ot

HCS iHarms et ai, 197.S). (B) The form ol stfatifi< ation iind ordered

bounding surfaces commonly found in HCS sandstone beds iCbeel

.ind Lcckie, 1993).

surfaces are produced by erosion that tnakes up a hunmiocky/

swaley surface on which internal laminae (bounded by third-

order surfaces) are draped as sediment is deposited on the

underlying hummocky surface. This mode of formation is

supported by the common observation that internal laminae

thicken from hummocks into the swales and become flatter

upward within an HCS set (Figures H4 and H5).

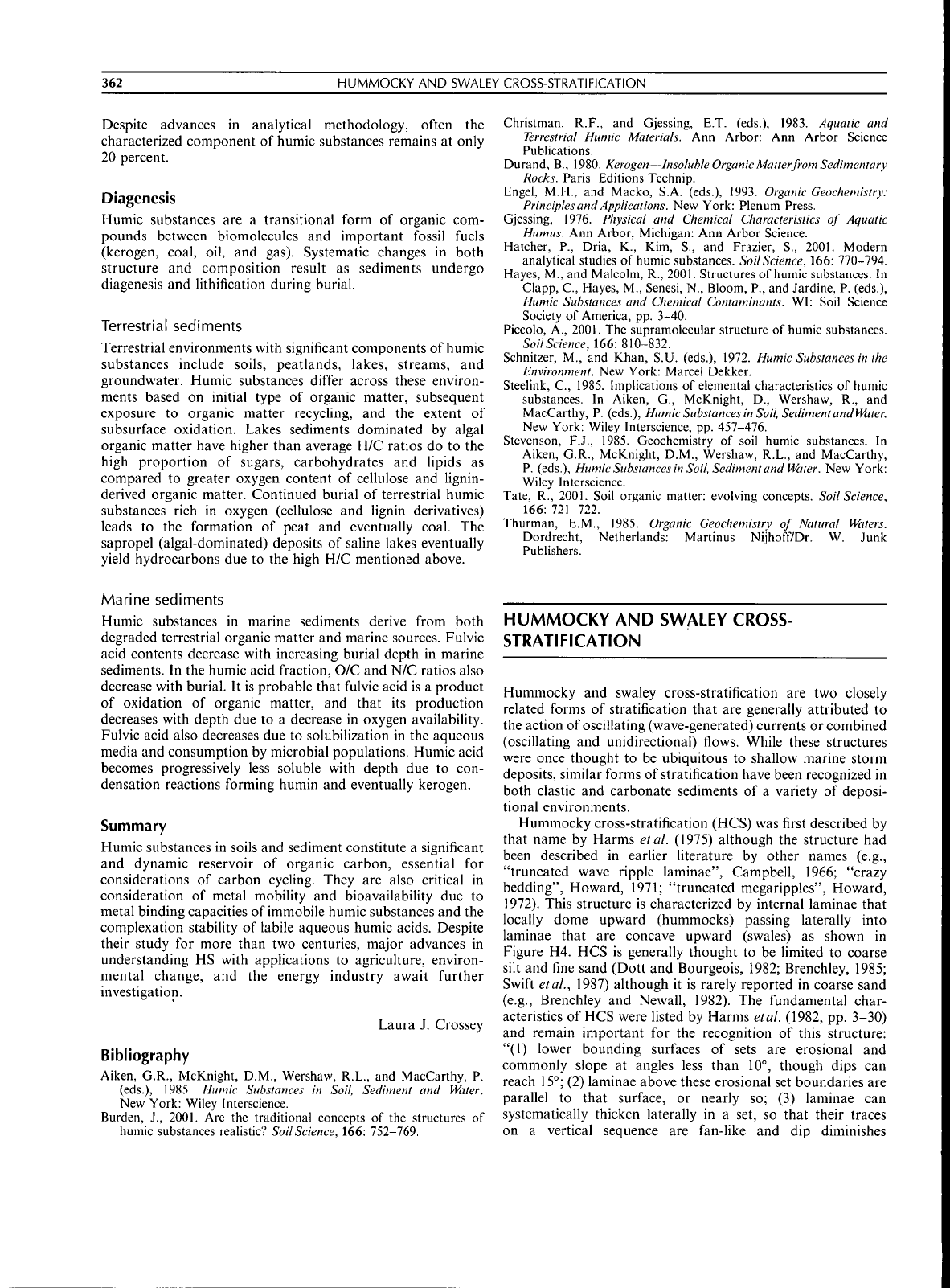

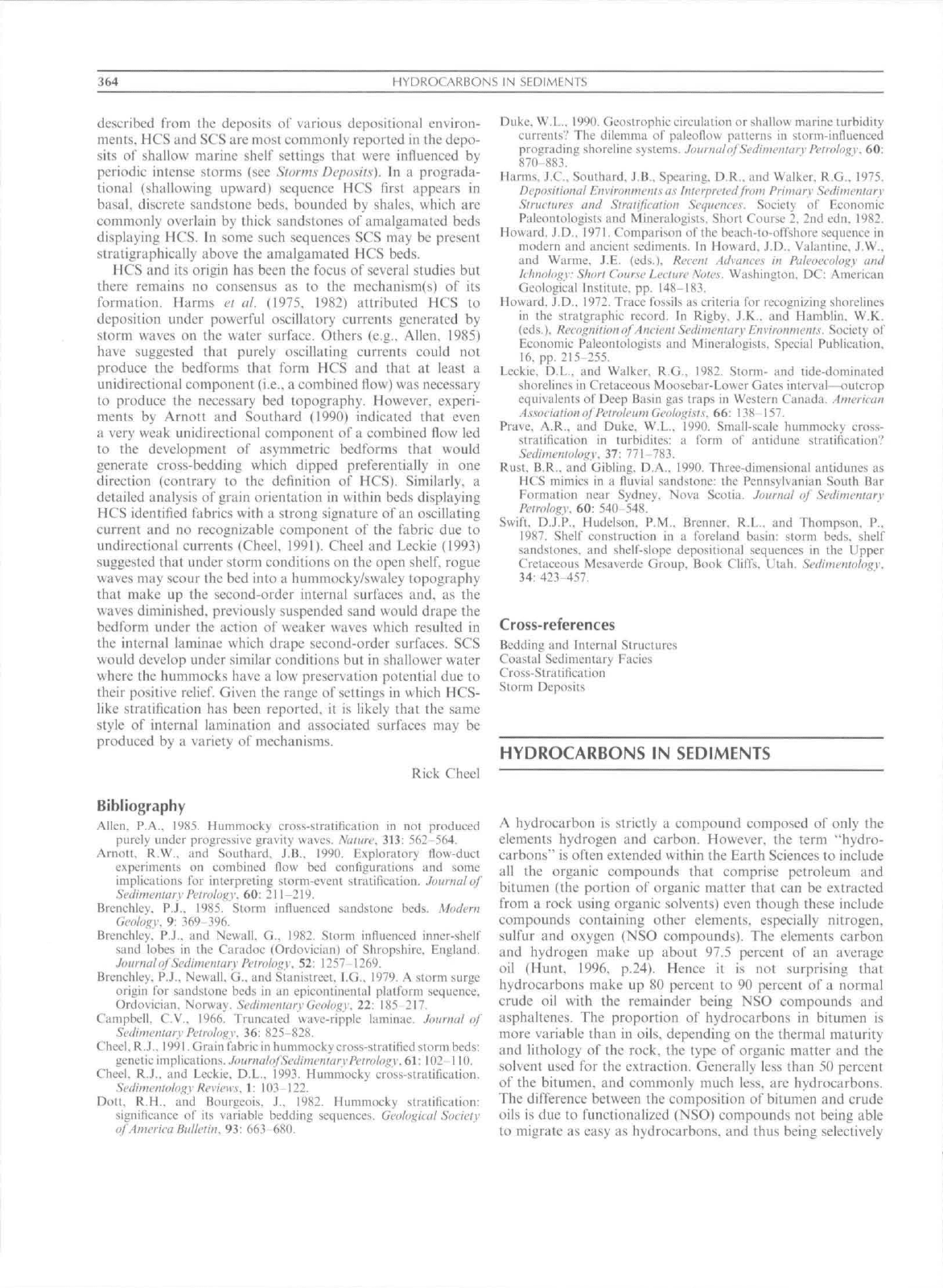

Swaley cross-stratification (I-igure H6) was first described

by Leckie atid Walker (1982). SCS is generally similar to HCS

but lacks the positive relief associated with hummocks. In

addition. Harms etat. (1982) stated that the ma.ximum dip of

second-order sets in SCS is somewhat shallower than HCS, not

exceeding 10 .

While HCS-like stratifieation (HCS "mimics'", for example,

Prave and Duke, 1990: Rust and Gibling, 1990) has been

Figure H6 SCS in out crop. Note ihe laryc, luvv-an^lo nilenial surfaces

ihat define that structure. Bar scale is approximately one meter

lonj;.

Photo courtesy of Dale Leckie.

Figure H5 HCS in outcrop showing

a

hummocky surface cutting into horizontally laminated sandstone, draped by laminae that thin from left to

right from the swale to the hummock. Bar for scale is a[5proximately 10 cm. Photo courtesy of Dale

Lee

kie.

364 HYDROCARBONS IN SEDIMENTS

described from the deposits of various depositional environ-

ments, HCS and SCS are most commonly reported in the depo-

sits of shallow marine shelf settings that were influenced by

periodic intense storms (see Storm.s Deposits). In a prograda-

tional (shallowing upward) sequence HCS first appears in

basal, discrete sandstotie beds, bounded by shales, which are

commonly overlain by thick sandstones of amalgamated beds

displaying HCS. In some such sequences SCS may be present

stratigraphically above the amalgarnated HCS beds.

HCS and its origin has been the focus of several studies but

there remains no consensus as to the mechanism(s) of its

formation. Harms et al. (1975. 1982) attributed HCS to

deposition under powerful oscillatory currents generated by

storm waves on the water surface. Others (e,g.. Allen, 1985)

have suggested that purely oscillating currents could not

produce the bedforms that form HCS and that at least a

unidirectional component (i^e.. a combined flow) was necessary

to produce the necessary bed topography. However, experi-

ments by Arnott and Southard (1990) indicated that even

a very weak unidirectional component of a combined flow led

lo the development of asymmetric bedforms that would

generate cross-bedding which dipped preferentially in one

direetion (contrary to the definition of HCS). Similarly, a

detailed analysis of grain orientation in within beds displaying

HCS identified fabrics with a strong signature of an oscillating

current and no recognizable component of the fabric due to

undirectional current^s (Cheel, 1991). Cheel and Leekie (1993)

suggested that under stortn eonditions on the open

shelf,

rogue

waves may seour the bed into a hummocky/swaley topography

that make up the second-order internal surfaces and. as the

waves ditninishcd, previously suspended sand would drape the

bedform under the action of weaker waves which resulted in

the internal latninae which drape second-order surfaces. SCS

would develop under similar conditions but in shallower water

where the hutnmocks have a low preservation potential due to

their positive

relief.

Given the range of settings in which HCS-

like stratification has been reported, it is likely that the same

style of internal lamination and associated surfaces may be

produced by a variety of mechanisms.

Rick Cheel

Bibliography

Allen. P.A.. 1985. Hummocky cross-stratification in not produced

purely under progressive gravity waves. Nature. 313: 562-564.

Arnotl. R.W., and Southard, J'B.. 1990. Exploratory tlow-duct

experiments on combined flow bed configurations and some

implications for inlerpreting slortn-event stratification. Journalof

Sedimentary Petrology. 60: 211-219.

Brenehley, PJ.. 1985. Storm infiuenced sandstone beds. Modern

Geology. 9: 369-396.

Brenehley, P.J., and Newall, G., 1982. Storm intliicnced inner-slielf

sand lobes in the Caradoc (Ordoviclan) of Shropshire, Eiiigland.

Journal of Sedimentary Petrology. 52: 1257-1269.

Brenehley, P.J., Newall, G., and Slanistreet, I.G., 1979. A storm surge

origin for sandstone beds in an epicontinental platform sequence,

Ordovician, Norway. Sedimentary Geology. 22: 185 217.

Campbell. C.V., 1966. Truncated wave-ripple laminae. Journal of

Sedimentary Petrology. 36: 825-828.

Cheel. R.J..

1991.

Grain fabric in liutntiiocky cross-stratified storm beds:

genetic implications. Journalol Sedimentary Petrology.

61:

102 II0.

Cheel, R.J.. and Leckie, D.L., 1993. Hummocky cross-stratification.

Sedimentology Reviews. 1: 103-122.

Dott, R.H., and Bourgeois. J., I9f^2. Humtnocky stratification:

significance of its variable bedding sequences. Geological Soeietv

ofAmeriea Bulletin. 9i: hbi 680.

Duke. W.L.. 1990. Gcostrophic circulation or shallow marine turbidity

currents.' The dilemma of paleoflow patterns in storm-intluenced

prograding shoreline systems. Journal of Sedimentary

Petrology.

60:

870-883.

Harms. J.C.. Southard. J.B., Spearing. D.R.. and Walker. R.G.. 1975.

Depositional Environments as Interpreted

from

Primary Sedimentary

Structures and Stratification Sequences. Society of Economic

Paleontologists and Mineralogists. Short Course 2. 2nd edn, 1982.

Howard. J.D., 1971. Comparison of the beach-1o-olTshere sequence in

modern and ancient sedimenls. In Howard, J.D.. Viikmtinc, J.W.,

and Warmc. J.F.. (eds). Recent Advances in Puleoeeohgy and

hhnotogy: Sluirt Course Eccturc Soles. Washington, DC: American

Geologiea! Institute, pp. 148-183.

Howard, J.D., i972. Trace fossils as criteria for recognizing shorelines

in the stiatgraphic record. In Rigby, J.K.. and Hamblin. W.K.

I

eds.),

Reeogniti(m of

.Ancient

Sedimentary Environments. Society of

Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists. Special Publication.

16.

pp. 215-255.

Leckie. D.L.. and Walker, R.G.. 1982. Storm- and tide-dominated

shorelines in Cretaceous Moosebar-Lower Gates interval—tiutcrop

equivalents of Deep Basin gas traps in Western Canada. American

Aswociatitm

of Petroleum

Geolof-ists.

66: 138 157.

Prave, A.R., and Duke, W.L., 1990. Small-scale hutnmocky cross-

stratification in turbidites: a form of antidune stratification?

Sedimemology. 37: 771-783.

Rust, B.R.. and Gibling. D.A.. 1990. Three-dimensional antidiines as

HC"S mimies in a l^uvial sandstone: the Pennsylvanian South Bar

Formation near Sydney. Nova Seotia. Journal of Sedimentary

Petrology. 60: 540-548.'

Swift, D.J.P., Hudelson. P.M., Brenner. R.L.. and Thompson, P.,

1987.

Shelf construction In a foreland basin: storm beds, shelf

sandstones, and shelf-slope depositional sequences in the Upper

Cretaceous Mesaverde Group, Book CliiTs, Utah. Sedimentology.

34:

423-457.

Cross-references

Bedding and Internal Structures

Coastal Sedimentary Tacics

Cross-Stratification

Storm Deposits

HYDROCARBONS IN SEDIMENTS

A hydrocarbon is strictly a cotnpound composed of only the

elements hydrogen and carbon. However, the term "hydro-

carbons'" is often extended within the Earth Sciences to include

all the organie compounds that comprise petroleum and

bitumen (the portion of organic matter that can be e.xtracted

from a rock using organic solvents) even though these include

compounds containing other elements, especially nitrogen,

sulfur and oxygen (NSO compounds). The elements carbon

and hydrogen make up about 97.5 percent of an average

oil (Hunt, 1996, p.24). Hence it is not surprising that

hydrocarbons make up 80 percent to 90 pereent of a normal

crude oil with the remainder being NSO compounds and

asphaltencs. The proportitin of hydrocarbons in bitumen is

more variable than in oils, depending on the thermal tnaturity

and lithology of the rock, the type of organic matter and the

solvent used for the extraction. Generally less than 50 percent

of the bitumen, and commonly much less, are hydrocarbons.

The difference between the composition of bitutnen and crude

oils is due to functionalized (NSO) compounds not being able

to migrate as easy as hydrocarbons, and thus being selectively