Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

HYDROCARBONS IN SFDIMFNTS

retained within

the

source rock

and to a

lesser extent

on

mineral surfaces along migration pathways.

Occurrences

Although hydrocarbons have been reported almost everywhere

in the earth's crust, they are

far

more abundant

in

sediments

than

in

igneous

or

metamorphic rocks. This reflects

the

biogenie origin

of

most hydrocarbons

in

sedimentary roeks.

Hydrocarbons make up

a

very low proportion

of

the biomass

and henee their abundanee in recent sediments is generally low,

in the 20ppm

to

100 ppm range (Tissot and Welte. 1984. p.95).

In aneient non-reservoir sediments, especially organic-rich,

fine-grained

rocks,

their abundance

is

much higher,

up to

several thousand

ppm. The

large scale accumulations

of

hydrocarbons within commercial

oil

fields

are due to

their

migration out

of

large volumes of source rocks and into more

permeable and porous beds where they have been trapped.

A diverse range of alkanes and aromatic hydrocarbons have

been reported

in

petroleum

and

sediments.

The

average

hydroearbon composition

of a

crude

oil has

been stated

to

be

?>?•

percent acyclic (normal

and

branched alkanes).

32

per

cent cycloalkanes

and 35

percent aromatic hydro-

carbons {Killops and Killops, 1993, p.137). These proportions

vi'ill vary depending on the nature of the organic matter

in

the

oil source rock

and the

level

of

thermal maturity, with

saturaled hydrocarbons becoming more predotninant at higher

tnaturity. Organic geochcmists usually analyze for compounds

with less than (brty carbon atoms, but the recent development

of high temperature gas chromatography

has

shown higher

molecular v\eight hydroearbons, up to

C1211

may be ubiquitous

in oils (Hsieh and Philp, 2001). The simplest and usually

the

most abundant hydroearbons are the straight-chain n-alkanes,

which

can

range from

C]

(methane)

to

C^d,..

Particularly

in

recent sediments,

the

C25-C13 n-alkanes often show

a

pronouneed

odd

carbon number preference. This

is due to

ihe predominance

of odd

carbon number n-alkanes

in

plant waxes. Simple branched alkanes sueh

as

the iso-alkanes

(2-methylalkanes) and anteiso-alkanes (3-mcthylalkanes) and

cyclic alkanes sueh

as the

eyelohexanes

and

cyclopentanes

with

a

similar carbon number range

to

the n-alkanes are also

ubiquitous

in

crude oils

and

ancient sediments. Many

hydrocarbons have carbon skeletons that can be easily related

10

a

precursor originally synthesized

by an

organism

(Figure H7). Such compounds

are

called biomarkers (short

for biological markers)

or

chemical fossil.s (Peters

and

Moldowan, 1993). Many

of

the most commonly found

and

abundant biomarkers are those that are based on the isoprcne

niiit. These include acyclic isoprenoids such

as

pristane (Ci^i)

and phytane (Ci^i)

and

cyclic compounds such

as

steranes.

OH

cholestane

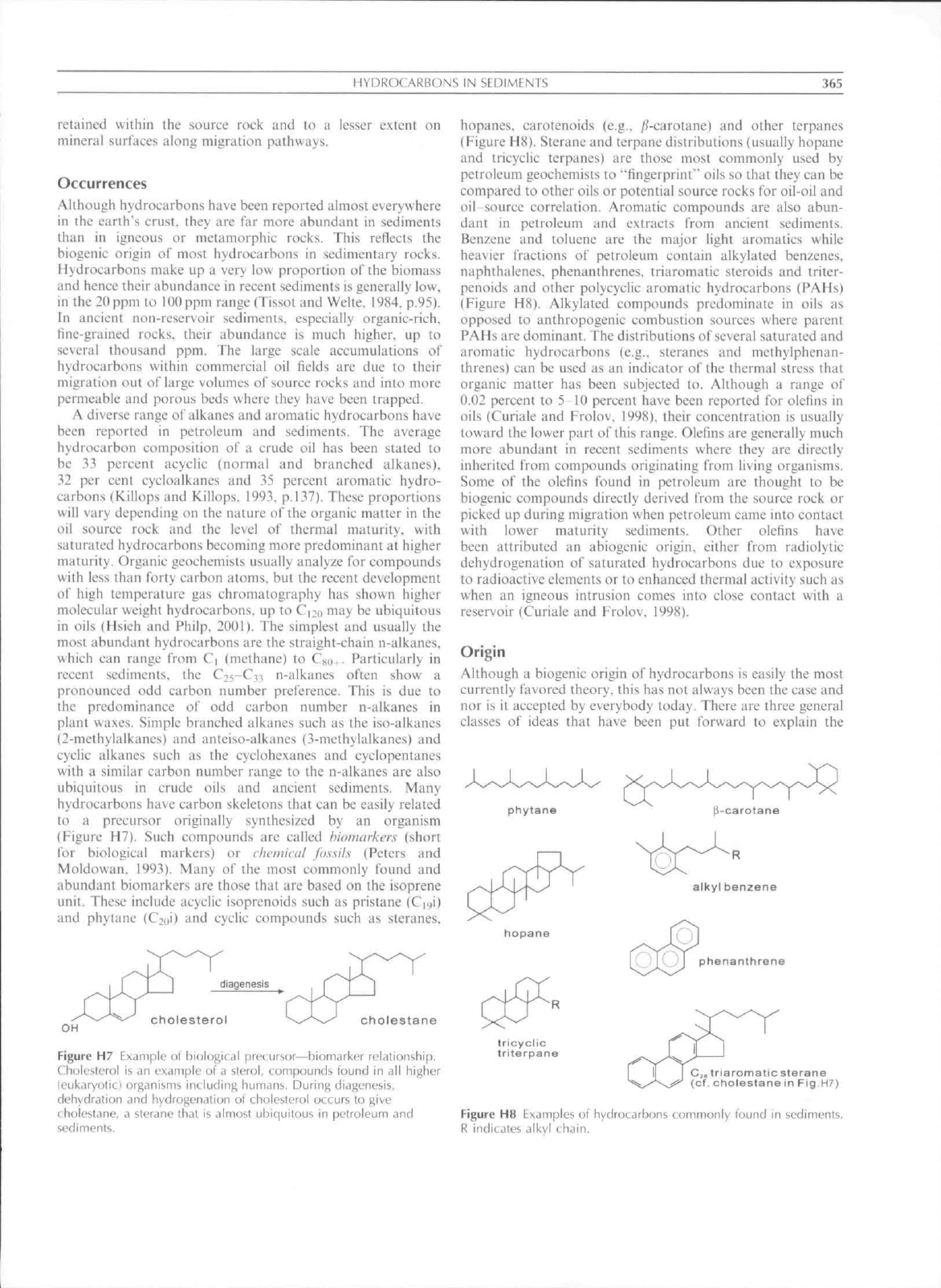

Figure H7 Example

of

biological precursor—biomarker relationship.

Cholesterol is an example of a sterol, compounds found

in

all higher

(euktiryolic) organisms inc luHinj; humnns. During diagenesis,

dehydration and hydrogendtion ol cholesterol occurs to give

cholestane, a sterane that is almost ubiquitous

in

petroleum and

sediments.

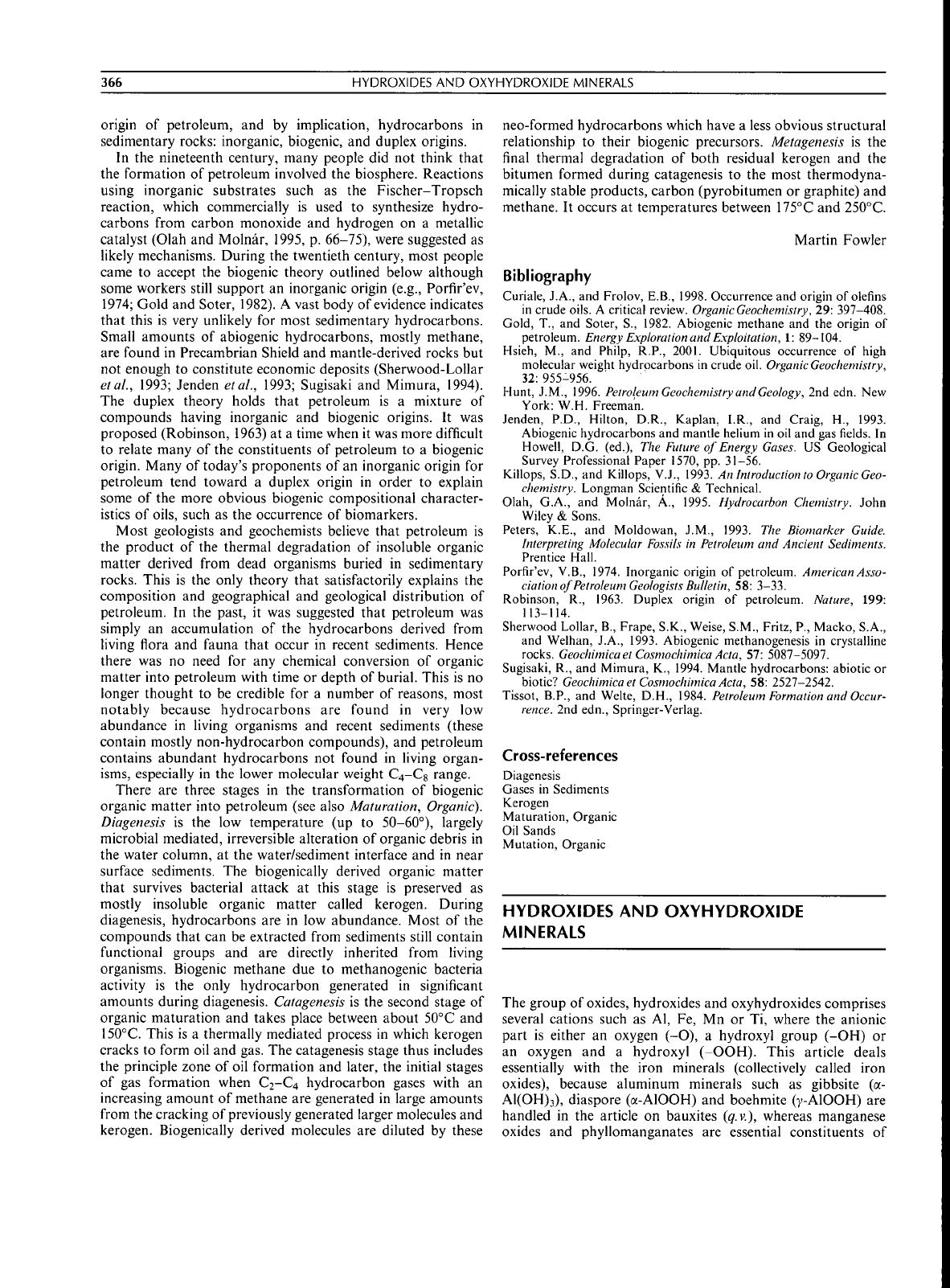

hopanes, carotenoids (e.g.. /^carotane)

and

other terpanes

(Figure H8). Sterane and terpane distributions (usually hopane

and tricyclic terpanes)

are

those most commonly used

by

petroleum geochemists to "fingerprint" oils so that they can be

compared to other oils or potential source rocks for oil-oil and

oil source correlation. Aromatic compounds

are

also abun-

dant

in

petroleum

and

extracts from aneient sediments.

Benzene

and

toluene

are the

major tight aromatics while

heavier fractions

of

petroleum contain alkylated benzenes,

naphthalenes, phcnanthrenes, triaromatic steroids and triter-

penoids and other polyeyelic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)

(Figure H8). Alkylated compounds predominate

in

oils

as

opposed

to

anthropogenic combustion sources where parent

PAHs are dominant. The distributions of several saturated and

aromatic hydrocarbons (e.g., steranes

and

methylphenan-

threnes) ean be used as an indieator

of

the thermal stress that

organic matter

has

been subjected

to.

Although

a

range

of

0.02 percent

to 5

10 pereent have been reported tor olefins

in

oils (Curiale and Frolov. 1998), their concentration

is

usually

toward the lower part of this range. Olefins are generally much

more abundant

in

recent sediments where they

are

directly

inherited from cotnpounds originating from living organisms.

Some

of the

olefins found

in

petroleum

are

thought

to be

biogenic compounds directly derived from the souree rock

or

picked up during migration when petroleum eame into eontaet

with lower maturity sediments. Other olefins have

been attributed

an

abiogenic origin, either from radioiytic

dehydrogenation

of

saturated hydrocarbons due

to

exposure

to radioactive elements or lo enhanced thermal activity such as

when

an

igneous intrusion comes into close contact with

a

reservoir (Curiale and Frolov, 1998).

Origin

Although

a

biogenic origin

of

hydrocarbons is easily the most

currently tavored theory, this has not always been the case and

nor is

it

accepted by everybody today. There are three general

classes

of

ideas that have been

put

forward

to

explain

the

phylane

[i-carotane

hopane

alkyl benzene

phenanthrene

tricyclic

triterpane

C,, triaromaticsterane

(cf. choleslanein Fig.H7)

Figure H8 Examples

of

hydrocarbons commonly found

in

sediments.

R indicates alkvi chain.

366

HYDROXIDES AND OXYHYDROXIDE MINERALS

origin of petroleum, and by imphcation, hydrocarbons in

sedimentary rocks: inorganic, biogenic, and duplex origins.

In the nineteenth century, many people did not think that

the formation of petroleum involved the biosphere. Reactions

using inorganic substrates such as the Fischer-Tropsch

reaction, which commercially is used to synthesize hydro-

carbons from carbon monoxide and hydrogen on a metallic

catalyst (Olah and Molnar, 1995, p. 66-75), were suggested as

likely mechanisms. During the twentieth century, most people

came to accept the biogenic theory outlined below although

some workers still support an inorganic origin (e.g., Porfir'ev,

1974;

Gold and Soter, 1982). A vast body of evidence indicates

that this is very unlikely for most sedimentary hydrocarbons.

Small amounts of abiogenic hydrocarbons, mostly methane,

are found in Precambrian Shield and mantle-derived rocks but

not enough to constitute economic deposits (Sherwood-Lollar

etal., 1993; Jenden etal., 1993; Sugisaki and Mimura, 1994).

The duplex theory holds that petroleum is a mixture of

compounds having inorganic and biogenic origins. It was

proposed (Robinson, 1963) at a time when it was more difficult

to relate many of the constituents of petroleum to a biogenic

origin. Many of today's proponents of an inorganic origin for

petroleum tend toward a duplex origin in order to explain

some of the more obvious biogenic compositional character-

istics of oils, such as the occurrence of biomarkers.

Most geologists and geochemists believe that petroleum is

the product of the thermal degradation of insoluble organic

matter derived from dead organisms buried in sedimentary

rocks.

This is the only theory that satisfactorily explains the

composition and geographical and geological distribution of

petroleum. In the past, it was suggested that petroleum was

simply an accumulation of the hydrocarbons derived from

living fiora and fauna that occur in recent sediments. Hence

there was no need for any chemical conversion of organic

matter into petroleum with time or depth of burial. This is no

longer thought to be credible for a number of reasons, most

notably because hydrocarbons are found in very low

abundance in living organisms and recent sediments (these

contain mostly non-hydrocarbon compounds), and petroleum

contains abundant hydrocarbons not found in living organ-

isms,

especially in the lower molecular weight C4-C8 range.

There are three stages in the transformation of biogenic

organic matter into petroleum (see also Maturation, Organic).

Diagenesis is the low temperature (up to 50-60°), largely

mierobial mediated, irreversible alteration of organic debris in

the water column, at the water/sediment interface and in near

surface sediments. The biogenically derived organic matter

that survives bacterial attack at this stage is preserved as

mostly insoluble organic matter called kerogen. During

diagenesis, hydrocarbons are in low abundance. Most of the

compounds that can be extracted from sediments still contain

functional groups and are directly inherited from living

organisms. Biogenic methane due to methanogenie bacteria

activity is the only hydrocarbon generated in significant

amounts during diagenesis. Catagenesis is the second stage of

organic maturation and takes place between about 50°C and

150°C. This is a thermally mediated process in which kerogen

cracks to form oil and gas. The catagenesis stage thus includes

the principle zone of oil formation and later, the initial stages

of gas formation when C2-C4 hydrocarbon gases with an

increasing amount of methane are generated in large amounts

from the cracking of previously generated larger molecules and

kerogen. Biogenically derived molecules are diluted by these

neo-formed hydrocarbons which have a less obvious structural

relationship to their biogenic precursors. Metagenesis is the

final thermal degradation of both residual kerogen and the

bitumen formed during catagenesis to the most thermodyna-

mically stable products, carbon (pyrobitumen or graphite) and

methane. It occurs at temperatures between 175°C and 250°C.

Martin Fowler

Bibliography

Curiale, J.A., and Frolov, E.B., 1998. Occurrence and origin of olefins

in crude oils. A critical review.

Organic

Geochemistry, 29: 397-408.

Gold, T., and Soter, S., 1982. Abiogenic methane and the origin of

petroleum. Energy Exploration and Exploitation, 1: 89-104.

Hsieh, M., and Philp, R.P., 2001. Ubiquitous occurrence of high

molecular weight hydrocarbons in crude oil.

Organic

Geochemistry,

32:955-956.

Hunt, J.M., 1996. Petroleum Geochemistry and

Geology,

2nd edn. New

York: W.H. Freeman.

Jenden, P.D., Hilton, D.R., Kaplan, I.R., and Craig, H., 1993.

Abiogenic hydrocarbons and mantle helium in oil and gas fields. In

Howell, D.G. (ed.). The Future of Energy Gases. US Geological

Survey Professional Paper 1570, pp. 31-56.

Killops, S.D., and Killops, V.J., 1993. An Introduction to Organic Geo-

chemistry. Longman Scientific & Technical.

Olah, G.A., and Molnar, A., 1995. Hydrocarbon Chemistry. John

Wiley & Sons.

Peters, K.E., and Moldowan, J.M., 1993. The Biomarker Guide.

Interpreting Molecular Fossils in Petroleum and Ancient Sediments.

Prentice Hall.

Porfir'ev, V.B., 1974. Inorganic origin of petroleum. American Asso-

ciationof Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, 58: 3-33.

Robinson, R., 1963. Duplex origin of petroleum. Nature, 199:

113-114.

Sherwood Lollar, B., Frape, S.K., Weise, S.M., Fritz, P., Maeko, S.A.,

and Welhan, J.A., 1993. Abiogenic methanogenesis in crystalline

rocks.

Geochimica et Cosmoehimiea Aeta, 57: 5087-5097.

Sugisaki, R., and Mimura, K., 1994. Mantle hydrocarbons: abiotic or

biotic? Geochimicaet Cosmoehimiea Acta, 58: 2527-2542.

Tissot, B.P., and Welte, D.H., 1984. Petroleum Formation and Occur-

rence. 2nd edn., Springer-Verlag.

Cross-references

Diagenesis

Gases in Sediments

Kerogen

Maturation, Organic

Oil Sands

Mutation, Organic

HYDROXIDES AND OXYHYDROXIDE

MINERALS

The group of oxides, hydroxides and oxyhydroxides comprises

several cations such as Al, Fe, Mn or Ti, where the anionic

part is either an oxygen (-0), a hydroxyl group (-0H) or

an oxygen and a hydroxyl (-OOH). This article deals

essentially with the iron minerals (collectively called iron

oxides), because aluminum minerals such as gibbsite (a-

AI(OH)3), diaspore (a-AlOOH) and boehmite (y-AlOOH) are

handled in the article on bauxites

{q.v.),

whereas manganese

oxides and phyilomanganates are essential constituents of

HYDROXIDES AND OXYHYDROXIDE MINERALS

367

iron-manganese nodules (^.

v.).

The TiO2 polymorphs rutile,

anatase and brookite are of minor importance in sediments

and sedimentary rocks.

Minerals

In sediments and sedimentary rocks, oxides (hematite a-Fe2O3,

magnetite Fe^"*"Fe2^O4, maghemite y-Fe2O3, wuestite FeO,

ilmenite FeTiO3) and oxyhydroxides (goethite a-FeOOH,

lepidocrocite y-FeOOH, ferrihydrite ~FeOOH) do occur.

Sehwertmannite, Fe8O8(OH)6SO4, is transitional between

oxyhydroxides and sulfates (for details see Cornell and

Schwertmann, 1996).

Occurrences

The iron contents of sediments are highly variable. On

average, carbonate rocks contain ca. 6mgg~

3,

sand-

2

stones ca. I4mgg~' and elaystones ca. 71mgg"'. The iron

oxides are either of detrital origin or neoformed in the

sediments. Titanomagnetites and ilmenite belong to those

detrital minerals that survive weathering due to high stability

in surface environments, and, hence, may concentrate, for

example, in placers (^.

v.),

up to mining quality. Hematite,

which is the major pigmenting mineral in red beds (^.

v.)

or any

other red-colored rock, may be either of detrital origin or it

formed diagenetically. The banded

iron

formations (BIF) or

itablrites are Precambrian, thin-bedded or laminated chemical

sediments, where hematite and magnetite are interbedded with

chert layers. In other kinds of sedimentary iron ores, hematite

may be associated with goethite and/or magnetite (see Iron-

stones and Iron Formations, and Flichtbauer, 1988). Yellowish

to brown colors indicate the presence of goethite, which is

present in small concentrations ubiquitously but in Paleozoic

and older rocks to a lesser extent than is hematite. Laterites

(^.

V.),

ferricretes and bauxites contain goethite, hematite and

also maghemite. Quaternary bog ores, which are the younger

analogs to ferricretes and bauxites, are dominated by goethite

and ferrihydrite, whereas hematite is absent. Tertiary sedi-

ments may contain lepidocrocite in addition to goethite.

Wuestite has been reported as rims around magnetite in

sandstones.

Properties

The basic structural unit in most of the iron oxides are Fe^"*"

cations coordinated by six anions (O^, and/or OH~). These

units are connected either by sharing one oxygen across a

corner, two oxygens across an edge or three along a face. With

the addition of fourfold coordinated Fe^'*' and/or Fe''''' cations

in the spinel phases, distinct structures with densities between

4gmL~' and 5.2gmL~' can arise by mixing several kinds of

bonds. In cases where one iron oxide is present, the color of

sediments {q.v.) is an indicative property. Variations in crystal

size,

however, or mixtures of two minerals (e.g., goethite and

hematite) not only change the hues, but also might mask other

iron oxides. Identification and characterization is therefore

better done by X-ray diffraction using Co radiation. Depending

on "crystallinity", detection limits may range from a few

mg g~' for micron-sized hematites in sandstones to ~0.2gg~'

for ferrihydrite. Mossbauer spectroscopy offers even lower

detection limits because of being sensitive to solely ^^Fe.

Crystal size and deviation from the ideal chemical composi-

tion reflect the physico-chemical environment in which

authigenic iron oxides have grown. In laterites, ferricretes,

and bauxites, crystal sizes of goethite and hematite range from

tens to hundreds of nanometers, whereas in sandstones

hematites may have grown to several microns in size. The

first mentioned environments with their intensive chemical

weathering yield also goethites and hematites, in which AP'*'

substitutes for Fe^+. Maximum substitutions of

O.33molmor' Al/(A1-|-Fe) have been found for goethites; in

hematites the substitution seems to be limited to

0.16molmol"'. Smaller crystal sizes and Al substitution

distinguishes iron oxides derived from supergene weathering

processes from those found in sandstones, carbonates and

other rocks, where crystal sizes are usually much larger and

substitution of foreign cations is almost absent.

Besides Al, other heavy metals such as V, Cr, Co, or Ni may

substitute in iron oxides, although with much lower absolute

contents. In ferricretes so much phosphate is associated with

iron oxides that it spoils their use as iron ores. Phosphate sorbs

strongly on iron oxide surfaces by forming a bidentate

mononuclear complex, in which two oxygens of the P04~

anion are shared with two surface oxygens (which were OH

groups before adsorption) bound to two Fe^'*' beneath the

surface. Selenite and sulfate adsorb similarly, but less strongly.

This kind of inner-sphere complexation has also been observed

for arsenate and chromate bound to sehwertmannite in

sediments from acid mine drainages.

Unpaired electrons of structural Fe(III) and Fe(II) result in

magnetic moments, which interact with each other and

depending on thermal motion produce magnetic ordering in

all iron oxides. The ordering temperatures of micronsized

crystals of magnetite, hematite and to some extent also

goethite are high enough (850, 956, and 400 K, respectively)

to preserve magnetizations even on a geological timescale.

When such particles settle freely during sediment formation,

they orient along the Earth's magnetic field and build up a

detrital remanent magnetization. Alternatively, a very stable

chemical remanent magnetization is acquired, when these iron

oxides grow authigenically in a sediment (see Dunlop and

Ozdemir, 1997).

Formation

Chemical weathering of primary, Fe(II)-containing silicates

liberates Fe^'"', which oxidizes and hydrolyses to form any of

the above-mentioned phases. Which iron oxide forms is

governed by pH, the rate of oxidation, the presence of

inorganic and organic anions, temperature, activity of Fe^'"'

and other foreign compounds. Near-neutral pH values and

higher temperatures favor formation of hematite over goethite.

With decreasing oxidation rates of Fe^^, ferrihydrite, lepido-

crocite or goethite are formed. In agreement with the

occurrences of less crystalline and less stable iron oxides in

younger sediments, kinetic factors seem to outweigh thermo-

dynamic stabilities, because at conditions prevailing in surficial

environments (i.e., low temperature, activity of water =1,

presence of oxygen), large crystals of goethite (a-FeOOH) are

the only thermodynamically stable phase. The ubiquitous

presence of hematite (a-Fe2O3) can be explained by lower

activities of water due to stronger binding of water in small

pores and/or due to higher temperatures, where hematite

becomes stable despite of a^fi =

1

{cf the formation of

368 HYDROXIDES AND OXYHYDROXIDE MINERALS

hematitic red beds

(^.v.)

in a warmer climate). A further factor,

which influences thermodynamic stability, is crystal size

because of increasing contributions of surface energy.

Transformation

By heating in dry conditions, all OH-containing oxides

transform finally to hematite via solid state reactions, but

depending on the nature of the compound, its crystallinity, the

extent of isomorphous substitution and other chemical

impurities, temperatures between 140°C and 500°C are

required. In the presence of water, dehydroxylation of goethite

to hematite requires hydrothermal conditions, whereas the

reverse reaction (hydroxylation of hematite) has not been

observed in situ because of kinetic hinderance. '^O isotope

measurements of such transformations have shown that a

solution step with transport via water molecules is always

involved (Bao and Koch, 1999).

The solubilities of Fe(ni) oxides at naturally occurring pH

values are so low that the concentration of Fe in solution is

orders of magnitudes lower than the solubility as Fe^'*'.

Although complexing organic compounds increase the total

solubility, the most efficient way to mobilize iron is by redu-

ctive processes mediated by bacteria or reducing compounds

(e.g., HS~). The high mobility of Fe^''' then allow redistribu-

tion of iron from the nanometer scale to landscapes. An

indicator for Fe^'*' as the feeding source is substitution of V^'*'

in lateritic goethites and hematites. Under natural pH and Eh

values, where Fe^"*' is stable, tetravalent VO^'*" coexists, but

not the unstable V^'^. A reduction VO^'^ to V^'^ followed by

incorporation is feasible, however, by a surface-mediated

reduction after sorption of Fe^'*' onto an oxide surface, which

decreases the redox potential of Fe'''''/Fe^''' in solution from

0.77 Volt to a value of ~0.35 Volt low enough to reduce

sorbed V''+ to V^+ (Schwertmann and Pfab, 1996).

Helge Stanjek

Bibliography

Bao,

H., and Koch, P.L., 1999. Oxygen isotope fractionation in ferric

oxide-water systems: low temperature synthesis. Geochimica

et Cosmoehimiea Acta, 63: 599-613.

Cornell, R.M., and Schwertmann, U., 1996. The Iron Oxides.

Weinheim: VCH...

Dunlop, D.J., and Ozdemir, O., 1997. Rock Magnetism. Cambridge

University Press.

Fuchtbauer, H., 1988. Sedimente und Sedimentgesteine. Stuttgart:

Schweizerbart.

Schwertmann, U., and Pfab, G., 1996. Structural vanadium and

chromium in lateritic iron oxides: genetic implications. Geochimica

et Cosmoehimiea Acta, 60: 4279-4283.

Cross-references

Bauxite

Colors of Sedimentary Rocks

Diagenesis

Iron-Manganese Nodules

Ironstones and Iron Formations

Laterites

Magnetic Properties of Sediments

Red Beds

ILLITE GROUP CLAY MINERALS

The term 'illite' usually is used in its petrographic sense as a

name for the K-rich, argillaceous component of sedimentary

rocks,

identified by ca.

1

nm spacing for its 001 X-ray

diffraction (XRD) peak. At 30 percent, illite is the second

most abundant mineral component of sedimentary rocks (after

quartz, 34 percent). Defined that way, it is not a mineral, but is

the "illitic fraction" of a rock, which, in addition to the

mineral illite, may contain admixtures of similar minerals,

most often fine-grained micas, glauconite and mixed-layer

illite-smectite. Used in the mineralogical sense, "illite"

identifies a clay structure, which is of 2:1 type, dioctahedral,

non-expanding, aluminous, and contains nonexchangeable K

as the major interlayer cation. The potassium balances a

negative layer charge, generated by Al for Si substitution in the

tetrahedral sheet and (Mg, Fe^"*") for Al in the octahedral sheet

(Figure II). This definition refers both to illite as a separate

mineral (discrete illite), and as a non-expanding component of

mixed-layer illite-smectite (I-S), known as the

illite

funda-

mental particle (Figure II). Due to its complicated chemical

composition and broad range of possible isomorphous

substitutions, illite becomes an important sink for most major

elements liberated at the Earth surface by interaction between

rocks and the hydrosphere. Thin illite crystals contribute

considerably to a rock's cation exchange capacity and they

reduce its permeability. Illite group minerals are covered in

detail in recent reviews by Srodoii (1999a,b).

Origin and evolution of illite in the rock cycle

Common surface environments are not favorable for the

formation of the mineral illite. Reports of illite formation in

weathering or marine environments often are misleading

because of eolian contamination (Sucha et al., 2001). Illite

may be partially stripped of its potassium by weathering and

may fix it back in sedimentary environment without changing

its silicate layers. Experiments indicate that smectites also may

fix potassium at surface temperatures without changing its

silicate layers, thus forming mixed-layer I-S during the process

of alternate wetting and drying, however, the geological

significance of this process has not been assessed. Illite can

be crystallized at surface temperatures at pH > 10 (Bauer etal.,

2000).

In natural high pH environments (lacustrine, playa),

ferruginous illite, having a composition intermediate between

illite and glauconite, is a common product of low-temperature

diagenesis.

Illitization becomes a major chemical reaction in

sedimentary rocks above approximately 70°C. Three types of

processes have been recognized: (1) alteration of smectite into

illite via mixed-layer I-S; (2) direct alteration of kaolinite and

feldspar into discrete illite; (3) crystalization of filamentous

illite in the pore space. The first process, volumetrically

dominant, is known in the most detail. Illitization of smectite

is a continuous process, producing pure non-expandable illite

at the bottom of the anchizone {ca. 275°C—this zone is the

highest grade of burial diagenesis). If not uplifted and eroded,

it gradually recrystallizes into coarse-grained mica up to 325°C

(biotite isograd, McDowell and Elders, 1980).

In the weathering environment, eroded illite is very stable

and commonly becomes recycled into new sediments either

chemically intact or partially stripped of its potassium (soil

vermiculite).

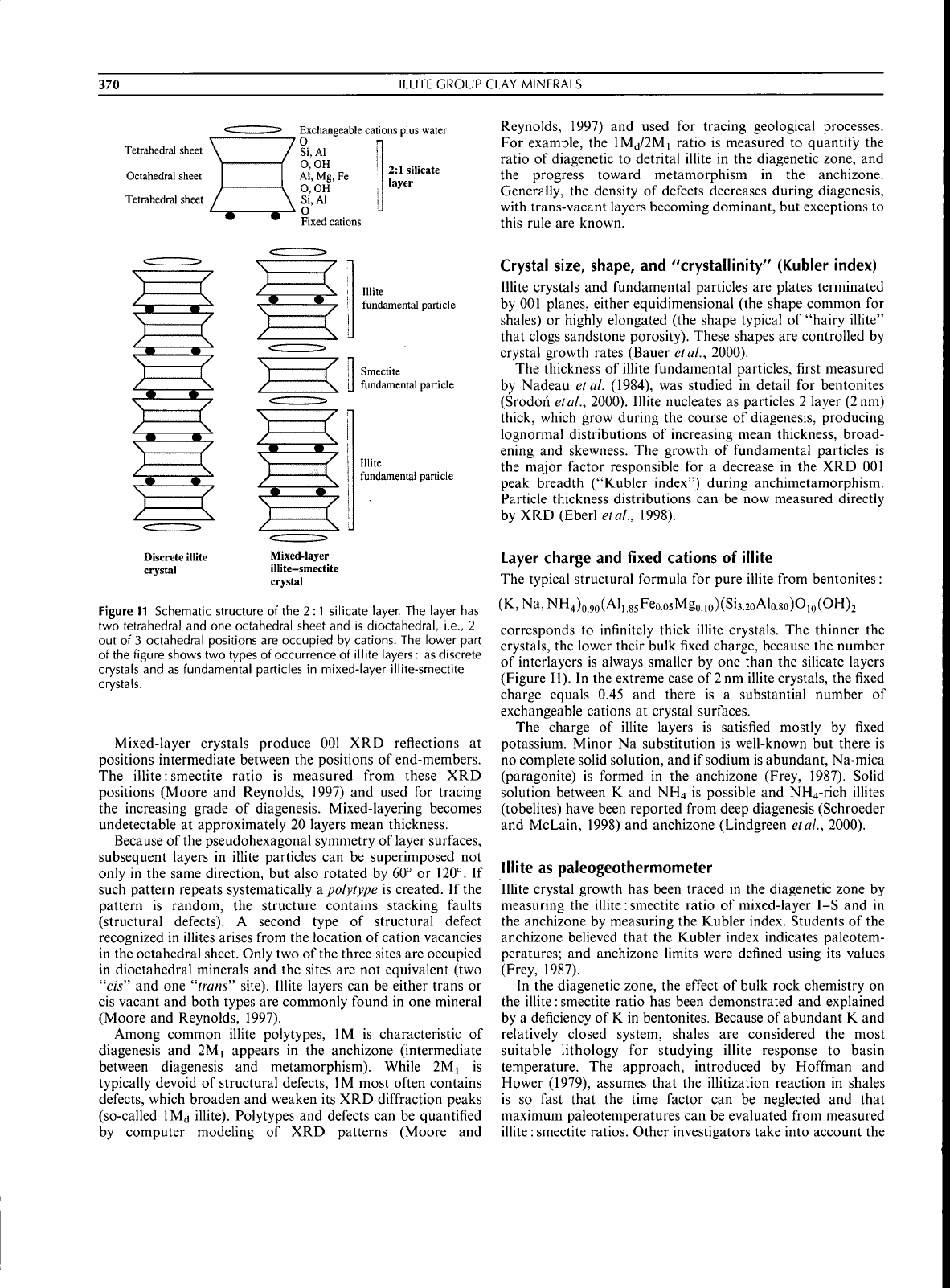

Mixed-layering, polytypes, and structural defects

Illite fundamental particles, which are only a few layers thick,

are very flexible. They can join each other or smectite

monolayers face-to-face to form multi-particle crystals

(Figure II), called mixed-layer crystals because the particle

interfaces display not illite but smectite characteristics (e.g.,

exchangeable cations, swelling properties). In the course of

diagenesis, smectite particles dissolve and illite particles grow

in thickness (Srodori etal., 2000), thus mixed-layering evolves

along with increasing percent of illite layers from so-called RO

(smectite monolayers plus illite bilayers) into Rl (no smectite

monolayers, bilayers dominant) and then R >

1

(3 nm or

thicker particles dominant).

370

ILLITE CROUP CLAY MINERALS

Tetrahedral sheet

Octahedral sheet

Tetrahedral sheet \ Si,

5-^ O

Exchangeable cations plus water

0

Si,Al

O.OH

Al,

Mg,

Fe

O.OH

AI

2:1 silicate

layer

Fixed cations

Reynolds, 1997) and used for tracing geological processes.

For example, the lM(j/2M| ratio is measured to quantify the

ratio of diagenetic to detrital illite in the diagenetic zone, and

the progress toward metamorphism in the anchizone.

Generally, the density of defects decreases during diagenesis,

with trans-vacant layers becoming dominant, but exceptions to

this rule are known.

\_

~7

Illite

fundamental particle

] ] \ Smectite

/ \ [J fundamental particle

^1

X

L

Discrete illite

crystal

Mixed-layer

illite-smectite

crystal

Illite

fundamental particle

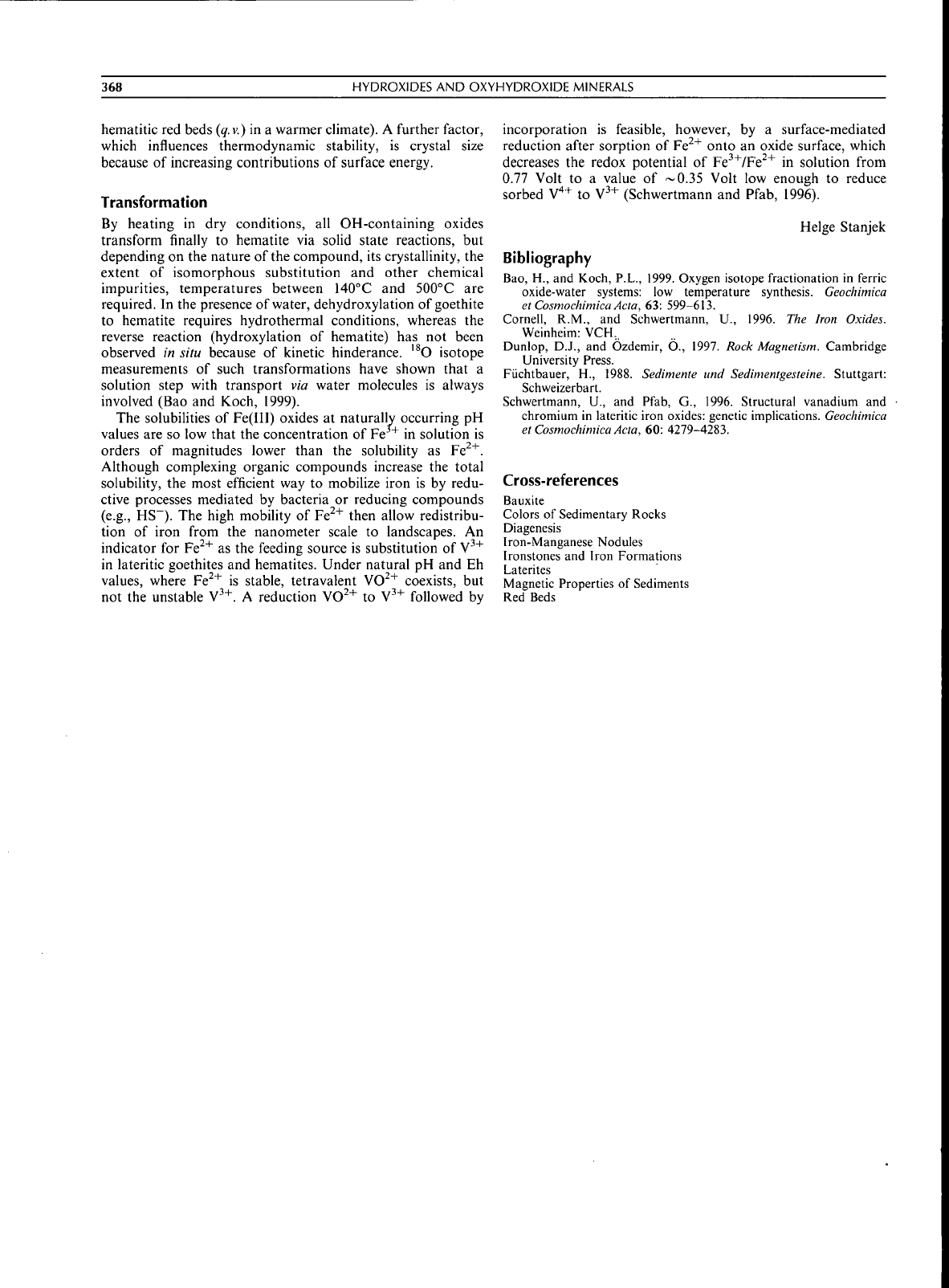

Figure II Schematic structure of the 2 :1 silicate layer. The layer has

two tetrahedral and one octahedral sheet and is dioctahedral, i.e., 2

out of 3 octahedral positions are occupied by cations. The lower part

of the figure shows two types of occurrence of illite layers: as discrete

crystals and as fundamental particles in mixed-layer illite-smectite

crystals.

Mixed-layer crystals produce 001 XRD reflections at

positions intermediate between the positions of end-members.

The illite: smectite ratio is measured from these XRD

positions (Moore and Reynolds, 1997) and used for tracing

the increasing grade of diagenesis. Mixed-layering becomes

undeteetable at approximately 20 layers mean thickness.

Because of the pseudohexagonal symmetry of layer surfaces,

subsequent layers in illite particles can be superimposed not

only in the same direction, but also rotated by 60° or 120°. If

such pattern repeats systematically a polytype is created. If the

pattern is random, the structure contains stacking faults

(structural defects). A second type of structural defect

recognized in illites arises from the location of cation vacancies

in the octahedral sheet. Only two of the three sites are occupied

in dioctahedral minerals and the sites are not equivalent (two

"cis"

and one "trans" site). Illite layers can be either trans or

cis vacant and both types are commonly found in one mineral

(Moore and Reynolds, 1997).

Among common illite polytypes, IM is characteristic of

diagenesis and 2M| appears in the anchizone (intermediate

between diagenesis and metamorphism). While 2M| is

typically devoid of structural defects, 1M most often contains

defects, which broaden and weaken its XRD diffraction peaks

(so-called lMj illite). Polytypes and defects can be quantified

by computer modeling of XRD patterns (Moore and

Crystal size, shape, and "crystallinity" (Kubler index)

Illite crystals and fundamental particles are plates terminated

by 001 planes, either equidimensional (the stiape common for

shales) or highly elongated (the shape typical of "hairy illite"

that clogs sandstone porosity). These shapes are controlled by

crystal growth rates (Bauer etal., 2000).

The thickness of illite fundamental particles, first measured

by Nadeau etal. (1984), was studied in detail for bentonites

(Srodori etal., 2000). Illite nucleates as particles 2 layer (2nm)

thick, which grow during the course of diagenesis, producing

lognormal distributions of increasing mean thickness, broad-

ening and skewness. The growth of fundamental particles is

the major factor responsible for a decrease in the XRD 001

peak breadth ("Kubler index") during anchimetamorphism.

Particle thickness distributions can be now measured directly

byXRD(Eberle?a/., 1998).

Layer charge and fixed cations of illite

The typical structural formula for pure illite from bentonites:

(K, Na, NHJo 5o(Al,

corresponds to infinitely thick illite crystals. The thinner the

crystals, the lower their bulk fixed charge, because the number

of interlayers is always smaller by one than the silicate layers

(Figure il). In the extreme case of 2nm illite crystals, the fixed

charge equals 0.45 and there is a substantial number of

exchangeable cations at crystal surfaces.

The charge of illite layers is satisfied mostly by fixed

potassium. Minor Na substitution is well-known but there is

no complete solid solution, and if sodium is abundant, Na-mica

(paragonite) is formed in the anchizone (Frey, 1987). Solid

solution between K and NH4 is possible and NH4-rich illites

(tobelites) have been reported from deep diagenesis (Schroeder

and McLain, 1998) and anchizone (Lindgreen etal., 2000).

Illite as paleogeothermometer

Illite crystal growth has been traced in the diagenetic zone by

measuring the illite: smectite ratio of mixed-layer 1-S and in

the anchizone by measuring the Kubler index. Students of the

anchizone believed that the Kubler index indicates paleotem-

peratures; and anchizone limits were defined using its values

(;Frey, 1987).

In the diagenetic zone, the effect of bulk rock chemistry on

the illite: smectite ratio has been demonstrated and explained

by a deficiency of K in bentonites. Because of abundant K and

relatively closed system, shales are considered the most

suitable lithology for studying illite response to basin

temperature. The approach, introduced by Hoffman and

Hower (1979), assumes that the illitization reaction in shales

is so fast that the time factor can be neglected and that

maximum paleotemperatures can be evaluated from measured

illite:

smectite ratios. Other investigators take into account the

IMBRICATION AND FLOW-ORIENTED CLASTS

371

time factor and chemistry and use various kinetic equations to

model the experimental illitization profiles.

K-Ar dating of illite

The interpretation of K-Ar dates depends on the type of host

rock. In pure beach or eolian sandstones all illite can be

authigenic (hairy illites) and the radiometric date indicates the

time of hot fluid flow and perhaps oil emplacement (Hamilton

etal., 1992). Shales, even in the finest fractions, usually contain

a mixture of authigenic and detrital illite. Techniques for

obtaining both ages have been proposed. If extracted properly,

the K-Ar date of diagenetic illite from shale represents the

mean time that has passed between the onset of illitization and

the time of maximum paleoternperature. This mean strongly

depends on burial history (Srodori et al., 2002). Many

bentonites are free of detrital contamination, but the K-Ar

date represents an even longer period of time than I-S from

surrounding shales because of slow diffusion of potassium into

the bentonite. This period of time can be evaluated by dating

bentonites that are zoned, that is, less highly illitized in the

center of the bed, and/or fractions of fundamental particles

separated from a bentonite.

Jan Srodori

Bibliography

Bauer, A., Velde, B., and Gaupp, R., 2000. Experimental constraints

on illite crystal morphology. Clay Minerals, 35: 587-597.

Eberl, D.D., Nuesch, R., Sucha, V., and Tsipursky, S., 1998.

Measurement of fundamental particle thicknesses by X-ray

diffraction using PVP-10 intercalation. Clays and Clay Minerals,

46:

89-97.

Frey, M., 1987. LowTemperatureMetamorphism. Blackie.

Hamilton, P.J., Giles, M.R., and Ainsworth, P., 1992. K-Ar dating of

illites in Brent Group reservoirs: a regional perspective. Geological

Society Special Publication, 61, pp. 377-340.

Hoffman, J., and Hower, J., 1979. Clay mineral assemblages as low

grade metamorphic geothermometers: application to the thrust

faulted disturbed belt of Montana, USA. SEPM, Special Publica-

tion, 26, pp. 55-79.

Lindgreen, H., Drits, V.A., Sakharov, B.A., Salyn, A.L., Wrang, P.,

and Dainyak, L.G., 2000. Illite-smectite structural changes during

metamorphism in black Cambrian Alum shales from the Baltic

area. American Mineralogist, 85: 1223-1238.

McDowell, S.D., and Elders, W.A., 1980. Authigenic layer silicate

minerals in borehole Elmore 1, Salton Sea geothermal field,

California, USA. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 74:

293-310.

Moore, D.M., and Reynolds, R.C., 1997. X-Ray Diffiaction and ihe

Identification and Analysis of Clay Minerals. Oxford University

Press.

Nadeau, P.H., Wilson, M.J., McHardy, W.J., and Tait, J., 1984.

Interstratified clay as fundamental particles. Science, 225: 923-925.

Schroeder, P.A., and McLain, A.A., 1998. Illite-smectites and the

influence of burial diagenesis on the geochemical cycling of

nitrogen. Clay Minerals, 33 : 539-546.

Srodori, J., 1999a. Use of clay minerals in reconstructing geological

processes: current advances and some perspectives. ClavMinerals,

34:

27-37.

Srodori, J., 1999b. Nature of mixed-layer clays and mechanisms of

their formation and alteration. Annual Review of Earth and

Planetary Sciences, 27:

19-53.

Srodori, J., Eberl, D.D., and Drits, V., 2000. Evolution of funda-

mental particle-size during illitization of smectite and

implications for reaction mechanism. Clays and Clay Minerals,

48:

446-458.

Srodori, J., Clauer, N., and Eberl, D.D., 2002. Interpretation of K-Ar

dates of illitic clays from sedimentary rocks aided by modelling.

Ameriean Mineralogist, 87: 1528-1535.

Sucha, V., Srodori, J., Clauer, N., Elsass, F., Eberl, D.D., Kraus, I.,

and Madejova, J., 2001. Weathering of smectite and illite-smectite

in Central-European temperate climatic conditions. Clay Minerals,

36:

403-419.

Cross-references

Bentonites and Tonsteins

Clay Mineralogy

Diagenesis

Fabric, Porosity, and Permeability

Glaucony and Verdine

Mixed-Layer Clays

Mudrocks

IMBRICATION AND FLOW-ORIENTED CLASTS

Imbrication is the overlapping arrangement of similar parts, as

of roof tiles or fish scales. The earliest use of "imbricate" or

related words by geologists quoted in the Oxford English Dic-

tionary are by Dana (1852, 1862) and by A. Geike (1858) to

describe biologic or paleontologic objects. An illustration of

sedimentary imbrication is given as early as Jamieson (1860),

reproduced here in Figure 12. A modified version of this figure

appears in the llth and 12th editions of Lyell's (1872, 1875,

p.

342) Principles, but neither Jamieson nor Lyell use any form

of the word "imbricate" in their discussions of the figures.

Imbrication, which is a special case of flow-oriented clasts, is

a common phenomenon, but observations and theory con-

cerning it are published rarely. The flow-orientation of a single

clast develops in many ways. To understand the flow

orientation of clasts in different environments can improve

interpretation of rocks, and lead to a better understanding of

sediment transport.

Imbricated clasts must have unequal lengths for their a, b, c

axes {a longest, c shortest). Usually, imbricated clasts are

approximately tabular in shape, where the a and b axes

significantly exceed the c axis. Roof tiles, or fish scales, or

tabular rock fragments can be imbricated; basketballs, or

grapes, or spherical sand grains cannot. As suggested by

Figure 12, imbricated clasts must be approximately similar in

absolute size: flat pebbles can form an imbricated group, but a

flat pebble cannot imbricate with a flat boulder.

Jamieson (1860, p. 350) suggests that flow orientation, such

as shown in Figure 12, "is best exemplified when the stones are

pretty large, say, from six to twelve inches in length."

However, flow orientation and imbrication occurs in finer

sediments, including sand (Gibbons, 1972), although com-

pared to pebbles or boulders, sand grains have more random

orientations because their size is smaller relative to the

turbulent eddies, and their submerged weight is relatively less

than the drag exerted by such eddies. On the larger scale,

boulders have been imbricated in debris flows and floods

(Blair, 1987, his figure 7C).

Sediment sorting determines the likelihood of imbrication.

A well-sorted collection of flat pebbles commonly contains an

imbricated array sueh as in Figure 12, but a poorly sorted sand

372 IMI^KICATION AND KLOW-ORIENTED CLASTS

Figure 12 An early illuslralion of imbricated and flow-orienteri clasts (lamjeson, 1860] and photos of the same phenomena trom the

ColoraHo Plateau. These illustrations and photos show regularly oriented clasts, where the d-b planes of the clasts dip down toward the

upstream direction. Full scale is 30cm.

with a gravel component will rarely contain imbricated pebble

arrays.

Regularly-oriented clasts

Isolated tabular clasts are easily oriented by flowing water.

Analysis of the fluid mechanics involved in overturning a

tabular clast suggests that there is a critical overturning Froude

number (V\) above which the clasts overturns,

IF;

= V/v/^ (Eq. I)

where V is the mean flow velocity affecting the clasts, g is the

acceleration due to gravity, and c is the thickness (short axis)

of the tabular clasts (Galvin. 1987). The critical overturning

value of F,, above which the tabular clast is oriented by the

flow, is about 3.0 to 3.5. This critical value decreases as the

suspended mud content of the water increases. The analysis

assumes that flow depth exceeds the a axis of the clast. a

condition where the immersed weight of the clast resisting the

overturning is significantly less than its weight in air.

Usually, the acceleration, g, in a Froude number can be

treated as just another constant necessary to make the units

balance, but Pathfinder photos of clasts on the surface

ol"

Mars

suggest that these clasts may be imbricated or flow-oriented.

The lower Martian value of

,<,'

to be used in equation 1 for

explaining this imbrication or clast orientation implies that a

given size clast overturns in flowing water on Mars when the

velocity is only about 62 percent that needed to overturn it on

Earth.

The expected orientation of an imbricated group

ol"

tabular

clasts or an isolated tabular clast is one in uhich the planes

containing the longer ((/. h) axes dip down toward the source

of the (low (Figtirc 12). For a clast in a stream, (his means that

the (/ h plane usually dips toward the upstream direction.

Clasts having this expected dip toward the upstream direction

are regularly oriented clasts.

Reversely-oriented clasts

On aclive foresct beds, there may be exceptions to this

upstream dip (Figure 13, top). On active foresets, isolated

clasts may dip in the down-slope direction parallel to. or more

steeply than, the slope

itself,

if turbulence shed by the clast

scours a hole at the downstream edge of the clast. and

(possibly) if grain flow exerts an overturning moment on the

upslopc edge of the clasl. Clasts whose a-b planes dip in the

downstream direction are reversely oriented clasts. so-called

because the dip is opposite that expected from intuition

developed by observations such as shown in Figure 12.

IMBRICATION

AND

FLOW-ORIENTED CLASTS 373

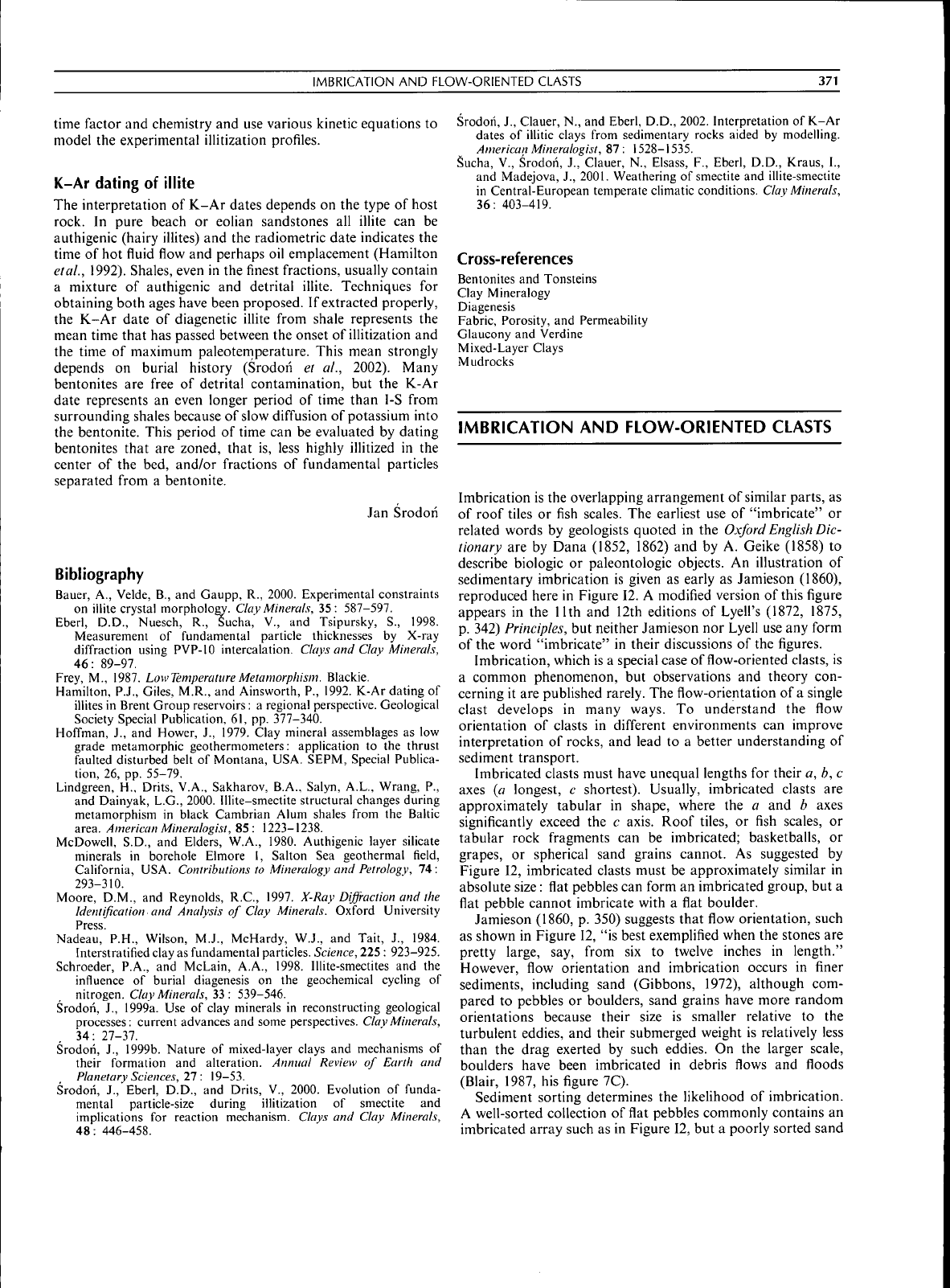

Figure 13 Reversely oriented clasts. Above: downstre.im

dip of

larger

pchhies

in ,i

s<indy member

of

the Cretaceous Potomac Eorm,5tion,

LorUin Sldlion, Virginia. The horizonlal

is

indit<3teri

by the

central

bubble

ol the

level. Inferred t'low

is

from right

ttj

left. Notice

the

(ollection

of

smaller pebbles

in ihe

wake

of the

large reversely

pebble.

At .i

higher level

in the

same outcTo|) where

the

is more nearly hori^onial, flow-oriented pebbles have

regularly inclined orienlation. Below:

in

Brushy Basin Member

of

Mori son

formation, reversely oriented blocky sandstone on "popcorn"

munlmorillorite shaie, apparently

the

result

ol

scour

on Ihe

downslope edge

of

the clasts during sheet flow runoff.

In arid regions it is common to tind clasts on eroding slopes

whose a b planes dip downslope more steeply than the slope

on vthich they rest. This commonly occurs when volcanic rocks

capping the uplands break up and slide down slopes of fine-

grained volcanic ash. Such an orientation of clasts (flints) in

surficial gravels were reported toward the end of his life by

Charles Darwin from the south of England. Probably, the

cause is runoff by overland sheet flow during rare, heavy

thunderstorms. For sheet llow, the water depth is typically less

than the <-axis, a condition where the effective weight of the

clast on the bottom is nearly that of its weight in air. The sheet

flow scours on the downslope side of the clasts. and the clast

settles into the scoured depression with the result that the a b

plane of the clast dips more steeply than the slope (Figure 13.

bottom). With respect to the presentation shoun in Figure 12,

the clasts in Figure 13 are reversely oriented because they dip

toward the downstream direction of the flow. Such orienta-

tions of the a b planes steeper than the underlying slope may

superficially resemble the condition produced by waves on

beaches.

Finally, a form of reversely oriented clasts develops when

wedge-shaped or pear-shaped clasls are subject (o sheet flow.

The thick end of the clast e.\erts more weight on the underlying

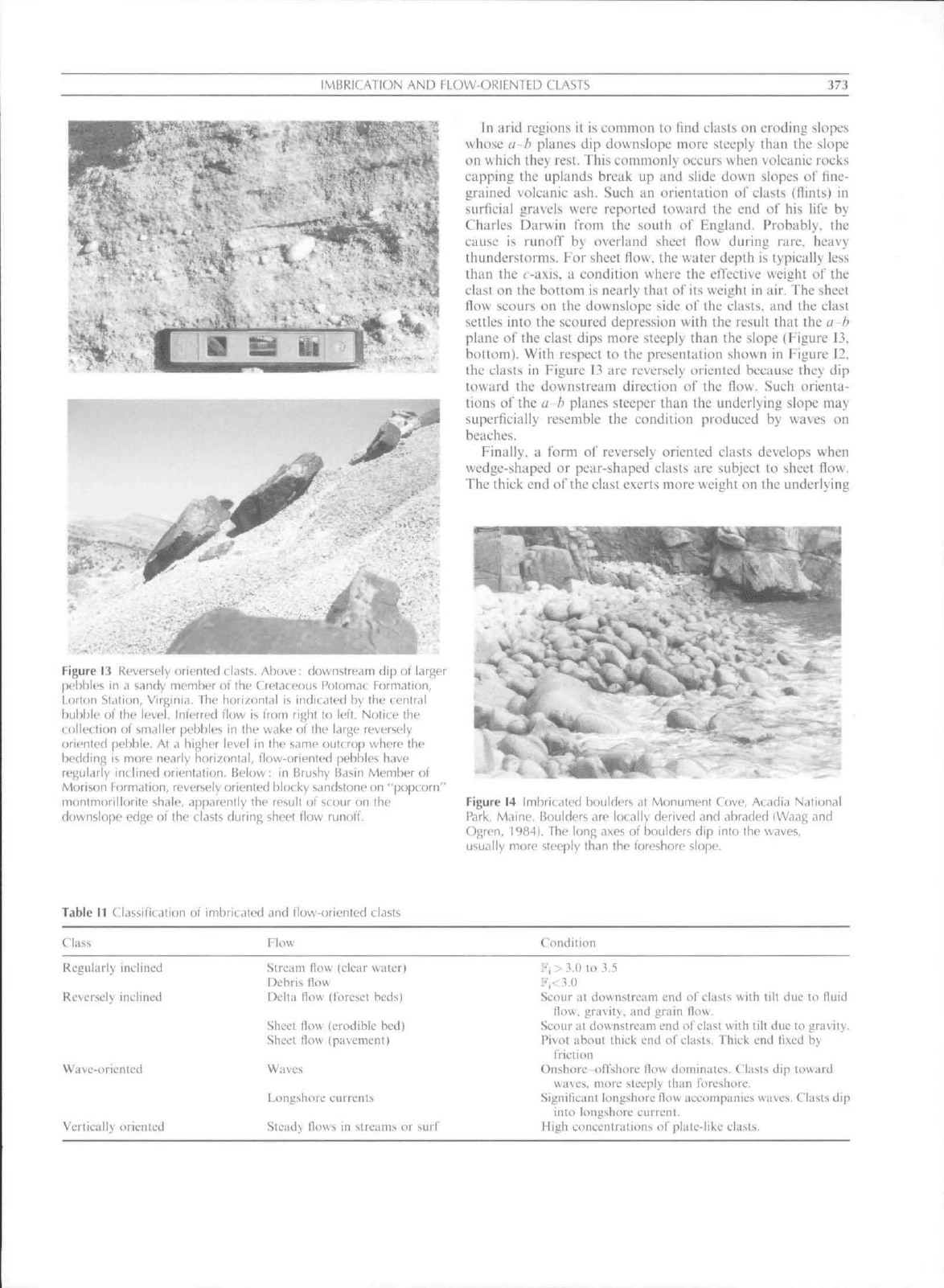

Figure 14 Imhricaled boulders

al

Monument Cove, Acadia Nalional

Park, Maine. Boulders

are

locally derived and abraded iWaag

and

Ogren,

1984). The long axes

of

boulders

dip

into the waves,

usually more steeply than

the

foreshore slope.

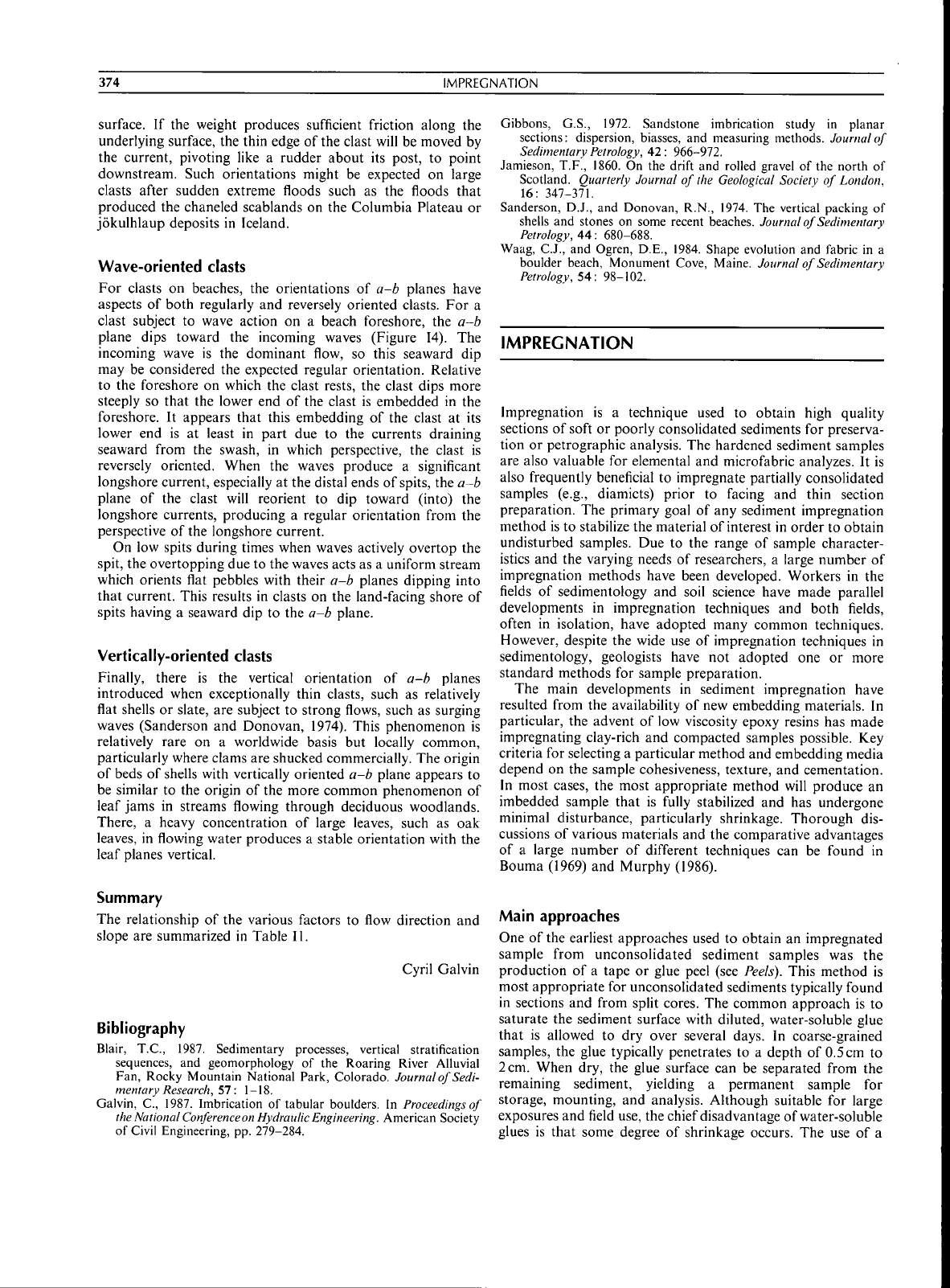

Table

II (

lassification

of

imbricated

and

flow-oriented clasts

Class

Flow C"ondition

Regularly inclined

Reversely inclined

Wiivc-orientcd

V'ertiai))v oricoK'tl

Stream flow (clear water)

Debris flow

Delta flow (i'oreset beds)

Sheet flow (erodible

bed)

Sheet flow (pavemciU)

Waves

Longshore

Sie;id\

tl(*\

Fi>3.nto

3.5

F|<3.0

Scour

at

downstream

end of

clasts wiih lilt

due lo

fluid

flow, gravity,

and

grain flow.

Scour

at

downstream

end of

cliisl

uUh

lilt due

to

gravity.

Pivot about Iliick

end of

clasls. Thick

end

fi.ved

by

friclioii

Onshore offshore tlow dominates. Cktsls

dip

loivard

wiives. more steepK than foreshore.

Signiiicani longshore flow aeeompanies waves. Cliisls

dip

into longshore current.

HiL'h concenlralions

of

plale-like clasts.

374

IMPREGNATION

surface. If the weight produces sufficient friction along the

underlying surface, the thin edge of the clast will be moved by

the current, pivoting like a rudder about its post, to point

downstream. Such orientations might be expected on large

clasts after sudden extreme floods such as the floods that

produced the ehaneled scablands on the Columbia Plateau or

jokulhlaup deposits in Iceland.

Wave-oriented clasts

For clasts on beaches, the orientations of a-b planes have

aspects of both regularly and reversely oriented clasts. For a

clast subject to wave action on a beach foreshore, the a-b

plane dips toward the incoming waves (Figure 14). The

incoming wave is the dominant flow, so this seaward dip

may be considered the expected regular orientation. Relative

to the foreshore on which the clast rests, the clast dips more

steeply so that the lower end of the clast is embedded in the

foreshore. It appears that this embedding of the clast at its

lower end is at least in part due to the currents draining

seaward from the swash, in which perspective, the clast is

reversely oriented. When the waves produce a significant

longshore current, especially at the distal ends of spits, the a-b

plane of the clast will reorient to dip toward (into) the

longshore currents, producing a regular orientation from the

perspective of the longshore current.

On low spits during times when waves actively overtop the

spit, the overtopping due to the waves acts as a uniform stream

which orients flat pebbles with their a-b planes dipping into

that current. This results in clasts on the land-facing shore of

spits having a seaward dip to the a-b plane.

Vertically-oriented clasts

Finally, there is the vertical orientation of a-b planes

introduced when exceptionally thin clasts, such as relatively

flat shells or slate, are subject to strong flows, such as surging

waves (Sanderson and Donovan, 1974). This phenomenon is

relatively rare on a worldwide basis but locally common,

particularly where clams are shucked commercially. The origin

of beds of shells with vertically oriented a-b plane appears to

be similar to the origin of the more common phenomenon of

leaf jams in streams flowing through deciduous woodlands.

There, a heavy concentration of large leaves, such as oak

leaves, in flowing water produces a stable orientation with the

leaf planes vertical.

Summary

The relationship of the various factors to flow direction and

slope are summarized in Table II.

Cyril Galvin

Bibliography

Blair, T.C., 1987. Sedimentary processes, vertical stratification

sequences, and geomorphology of the Roaring River Alluvial

Fan, Rocky Mountain National Park, Colorado. Journai of Sedi-

mentary Researcit, 57: 1-18.

Galvin, C, 1987. Imbrication of tabular boulders, tn Proceedings of

lite

National Conferenceon Hydraulic Engineering. American Society

of Civil Engineering, pp. 279-284.

Gibbons, G.S., 1972. Sandstone imbrication study in planar

sections: dispersion, biasses, and measuring methods. Journai of

Sedimentary

Pelroiogy,

42

:

966-972.

Jamieson, T.F., I860. On the drift and rolled gravel of the north of

Scotland. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London,

16:

347-371.

Sanderson, D.J., and Donovan, R.N., 1974. The vertical packing of

shells and stones on some recent beaches. Journal of Sedimentary

Petrology, 44: 680-688.

Waag, C.J., and Ogren, D.E., 1984. Shape evolution and fabric in a

boulder beach, Monument Cove, Maine. Journal of Sedimentary

Petrology, 54: 98-102.

IMPREGNATION

Impregnation is a technique used to obtain high quality

sections of soft or poorly consolidated sediments for preserva-

tion or petrographic analysis. The hardened sediment samples

are also valuable for elemental and microfabric analyzes. It is

also frequently beneficial to impregnate partially consolidated

samples (e.g., diamicts) prior to facing and thin section

preparation. The primary goal of any sediment impregnation

method is to stabilize the material of interest in order to obtain

undisturbed samples. Due to the range of sample character-

istics and the varying needs of researchers, a large number of

impregnation methods have been developed. Workers in the

fields of sedimentology and soil science have made parallel

developments in impregnation techniques and both fields,

often in isolation, have adopted many common techniques.

However, despite the wide use of impregnation techniques in

sedimentology, geologists have not adopted one or more

standard methods for sample preparation.

The main developments in sediment impregnation have

resulted from the availability of new embedding materials. In

particular, the advent of low viscosity epoxy resins has made

impregnating clay-rich and compacted samples possible. Key

criteria for selecting a particular method and embedding media

depend on the sample cohesiveness, texture, and cementation.

In most cases, the most appropriate method will produce an

imbedded sample that is fully stabilized and has undergone

minimal disturbance, particularly shrinkage. Thorough dis-

cussions of various materials and the comparative advantages

of a large number of different techniques can be found in

Bouma (1969) and Murphy (1986).

Main approaches

One of the earliest approaches used to obtain an impregnated

sample from unconsolidated sediment samples was the

production of a tape or glue peel (see Peeis). This method is

most appropriate for unconsolidated sediments typically found

in sections and from split cores. The common approach is to

saturate the sediment surface with diluted, water-soluble glue

that is allowed to dry over several days. In coarse-grained

samples, the glue typically penetrates to a depth of 0.5 cm to

2 cm. When dry, the glue surface can be separated from the

remaining sediment, yielding a permanent sample for

storage, mounting, and analysis. Although suitable for large

exposures and field use, the chiefdisadvantage of water-soluble

glues is that some degree of shrinkage occurs. The use of a