Middleton G.V. (Ed.) Encyclopedia of Sediments and Sedimentary Rocks

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

IMPREGNATION

375

tacky acetate sheet applied to the sediment surface is an

alternate approach that avoids the subsequent shrinkage

problem. However, the acetate peel can only bond to sur-

face grains and may not provide a complete, representative

sample.

A more common approach to imbedding involves filling the

entire sample with a cement to preserve the sedimentary

structures. In practice, a large number of possible embedding

materials exist, and availability varies in different areas. In

general, embedding media can be characterized as either water-

soluble or insoluble. Soluble materials are useful when the

sample is wet, such as recent lacustrine or marine sediments.

The two most common soluble materials include diluted

ordinary glue and polyethylene glycol (PEG). The sample is

immersed in the liquid embedding material and allowed to

soak for several days or longer to allow the embedding fluid to

fully infiltrate the sample. Generally, the PEG used for

embedding is a high molecular weight (> 800) variety and is

a waxy solid at room temperature. The PEG flakes must be

melted by the application of heat during the soaking process.

Although the water-soluble media are nontoxic and require no

specialized equipment to use, they often result in some

shrinkage, are generally too soft for thin sectioning, require

non-aqueous grinding fluids, and they have poor optical

properties.

Water insoluble media are generally either epoxy or acrylic

resins that require the sample to be dehydrated prior to

embedding to obtain full polymerization of the resin com-

pounds. While air or oven drying may be suitable for sandy or

gravelly samples, finer textured samples will crack and shrink

during drying, and the dry permeability of the sample will

often be too low to allow full infiltration of the embedding

material, especially into the center of larger samples.

Two common methods for dehydrating samples to minimize

shrinkage are to sublimate the sample water under vacuum

(freeze drying) or by using repeated liquid-liquid replacements.

Freeze drying effectively d.ehydrates samples of all textures,

although many commercial units are limited to small samples

(less than a few centimeters). Where suitable equipment is

available, freeze-drying produces minimal disturbance of

the sample if the sample is first frozen with liquid nitrogen

(Bouma, 1969). Pre-freezing is particularly important for clay-

rich samples, as the rapid freezing in nitrogen prevents the

formation of large ice crystals in the sample that result in voids

in the embedded sample. However, some ice crystal formation

tends to occur in very fine clay units, particularly if the

sediment sample .is more than

1

cm thick. Depending on the

rate of sample drying and the sediment composition, some

minor shrinkage may also occur and cracks may form at

sedimentary contacts. Moreover, the freeze-dried samples are

extremely fragile and coarse units may require support to

prevent collapse during handling.

The second approach to dehydrating samples involves

replacing the pore water with a water and resin miseible

solution. Most epoxy resins are compatible with acetone and

various alcohols. By replacing the pore water with such a fluid,

there is no shrinkage or disturbance to the sedimentary

structures. This method is suitable for a variety of sediments

including those from clay-rich lacustrine, marine, and glacio-

genic environments. The wet samples are submerged in the

replacement fluid that is left to fully infiltrate into the sample,

often for one or more days. The fluid is then drawn off and

replaced with fresh solution until the specific gravity of the

supernatant indicates that the water content is below

1

percent

(or less). Liquid-liquid replacement dehydration of samples

results in the least disturbance of samples, as there is no

shrinkage or danger of ice crystal casts in the final embedded

sample. However, the process is time consuming and uses a

large amount of the exchange fluid and resin. In some cases,

application of a light vacuum during the resin infiltration can

avoid extra resin waste.

Selection of the embedding resin varies considerably among

users,

ranging from slow curing acrylics (months) to rapid

curing epoxies (hours). Some epoxy resins that cure rapidly are

unsuitable because they are strongly exothermic and can

disturb the sample. Depending on circumstances, a variety of

resins can be used (Tippkotter and Ritz, 1996). Low viscosity

resins used for embedding histologieal and material samples

are readily available and suitable for fine-grained lacustrine

and marine sediments. Less specialized, higher viscosity resins

are suitable for coarser samples. Most require curing in an

oven to fully polymerize. The advantages of impregnating

samples with resin include standard handling procedures for

thin section preparation, excellent optical characteristics, and

permanent preservation of the sample. Compared to water-

soluble media, impregnating samples with resin is often time

consuming and relatively expensive. Moreover, more specia-

lized equipment is required, including facilities to handle what

are typically toxic chemicals.

Partial curing of an impregnated block, especially with

epoxy resins, usually indicates the presence of water in the

sample or poor resin infiltration. Increased infiltration

times using resins with long working times can avoid this

problem, and light vacuum may also accelerate infiltration. In

some situations, samples with incomplete infiltration can still

be cut and the exposed face treated with resin to complete the

stabilization prior to mounting (Carr and Lee, 1998).

Impregnation of sedimentary samples has proven to be a

valuable technique for geologists working in a wide range of

environments where sample preservation and microscopic

analysis has been limited by poorly consolidated materials. A

number of methods are available for impregnation, depending

on sample texture and moisture content. Samples that are

dehydrated and embedded with epoxy resins are suitable for

most applications, although simpler methods are available

as well.

Scott F. Lamoureux

Bibliography

Bouma, A.H., 1969. Methods for the Study of Sedimentary Structures.

John Wiley & Sons.

Carr, S.J., and Lee, J.A., 1998. Thin-section production of diamicts:

problems and solutions. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 68:

217-220.

Murphy, C.P., 1986. Thin Section Preparation of Soils and Sediments.

Berkhansted; A B Academic.

Tippkotter, R., and Ritz, K., 1996. Evaluation of polyester, epoxy and

acrylic resins for suitability in preparation of soil thin-sections for

insitu biological studies. Geoderma, 69: 31-57.

Cross-references

Bedding and Internal Structures

Fabric, Porosity, and Permeability

Relief Peels

376 IRON-MANGANESE NODULES

IRON-MANGANESE NODULES

Blaek

to

dark brown spheroidal

to

diseoida! coneretions of iron

and manganese oxyhydroxides. generally

a tew em in

diameter.

that cover extensive areas ot'the oeean floor

in ail

water depths

as well

as

the bottoms of some temperate latitude lakes (Figures

15

and

16).

The

ferromanganese oxyhydroxides

are

intimately

mixed with mineral

and

rock fragments

and

fossil debris,

and

occur

as

concentric layers arranged around

a

central nucleus

or

core consisting

of

rock fragments (generally volcanic), fossils

(e.g.. fish teeth, whale

ear

bones,

etc.) or

broken nodules.

Surfaces

are

either smooth

or

granular. Nodules

are

highly

porous

and

have

dry

bulk densities ranging from l.2gcm

to

1.6gcm~"

depending

on the

chemical composition.

Distribution and abundance

Nodules

are

most abundant

on the

sediment surface

and

occur

sporadically wilhin

the

seafloor sediment. Sampling

and

bottom photography

has

shown that average surface concen-

trations

of

lOkgm

~.

reaching

a

maximum

of

about

35kgm~^,

are

typical

of

vast areas

of the

Indian

and

Pacilic

seafloors between

4

km

and

5 km water depth.

The

highest

concentrations

are

found where

the

sediment accumulates very

slowly,

so

that

the

nodules

are not

covered

and

buried. Hence,

dense pavements

of

nodules

are

eharacteristic ol"

the

central

ocean basins most remote from continental sediment supply.

Similar

Mn and Fe

deposits

are

found

on

northern European

shelves,

the

Bailie

Sea and

some tjords. Ferromanganese

oxyhydroxides also oeeur

as

crusts

and

coatings

on

rock

and

mineral surfaees, especially

on

seamounts

and

similar topo-

graphic elevations throughout

the

oeean basins.

Ferromanganese nodules

are

locally abundant

on the

floors

of temperate zone lakes, such

as

those

of

Scandinavia

and

eastern North America (Cronan

and

Thomas, 1970). They

occur

as

spherical

and

discoidal nodules

and as

coatings

on

rock surfaces.

Growth rate

The rate

of

accretion

of

ferromanganese nodules

and

crusts

has been determined

by

dating rock nuclei

by the

K/Ar method

(Barnes

and

Dymond, 1967),

and by

measuring

the

decay

of

natural uranium series (""""Th.

""Pa) or

cosmogenie

(' Be)

nuclides

in the

oxyhydroxide layers (Ku.

in

Glasby. 1977).

The

median rate obtained with these different methods

is

around

5 mm/Ma, with

a

range

of <1

mm/Ma

to >

50 mm/Ma.

In

contrast,

the

rate

of

accumulation

of

associated sediment

is

of order I mm/Ka

to

5mm/Ka. This discordance,

and ihe

puzzling fact that most deep-sea nodules

arc

found

at

the sediment surface, implies that they must

be

maintained

at

the

sediment-water interface

for

very long time periods.

Occasional disturbance

of the

seafloor.

by

currents, slumping

or

the

activities

of

benthic fauna,

is

probably sufficient

to

remo\e sediment from

the

tops

of the

nodules

and to

turn

them over from time

to

time (Piper

and

Fowler, 1980).

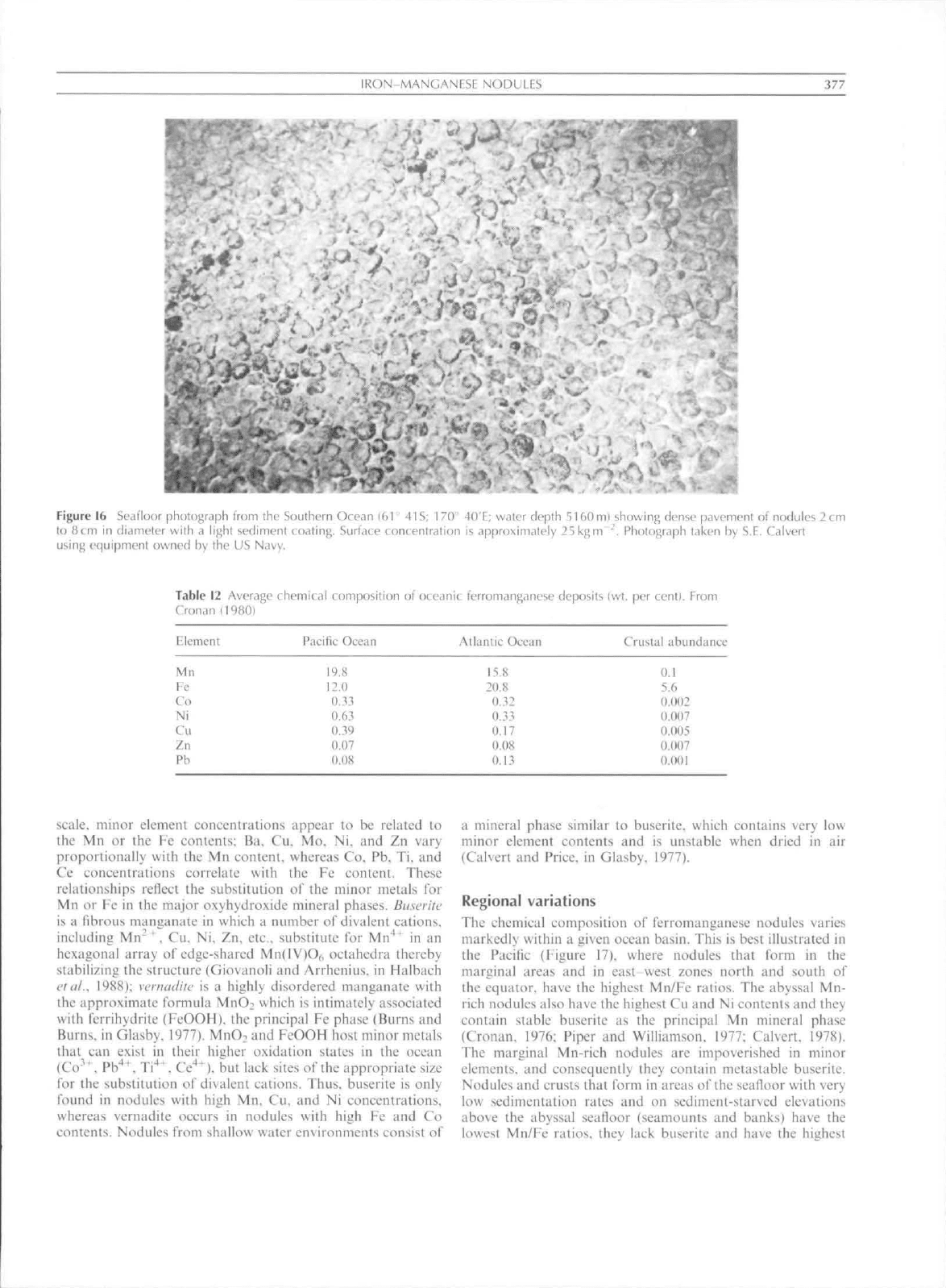

Chemical composition

The chemical composition

of

ferromanganese nodules

and

crusts reflects their constituent mixtures

of

mineral phases,

comprising oxyhydroxides, aluminosilicates. carbonates

and

phosphates. They

are

significantly enriched

in Mn. Fc and

other transition metals compared with crustal rocks. Mn/Fe

ratios

are

generally greater than unity

and Cu and Ni

coneentrations

are

highest

in the

Pacific Ocean, whereas

Mn/Fe ratios

are

less than unity

and Zn and Pb

concentrations

are highest

in the

Atlantic Ocean (Table 12).

On an

ocean-wide

cm

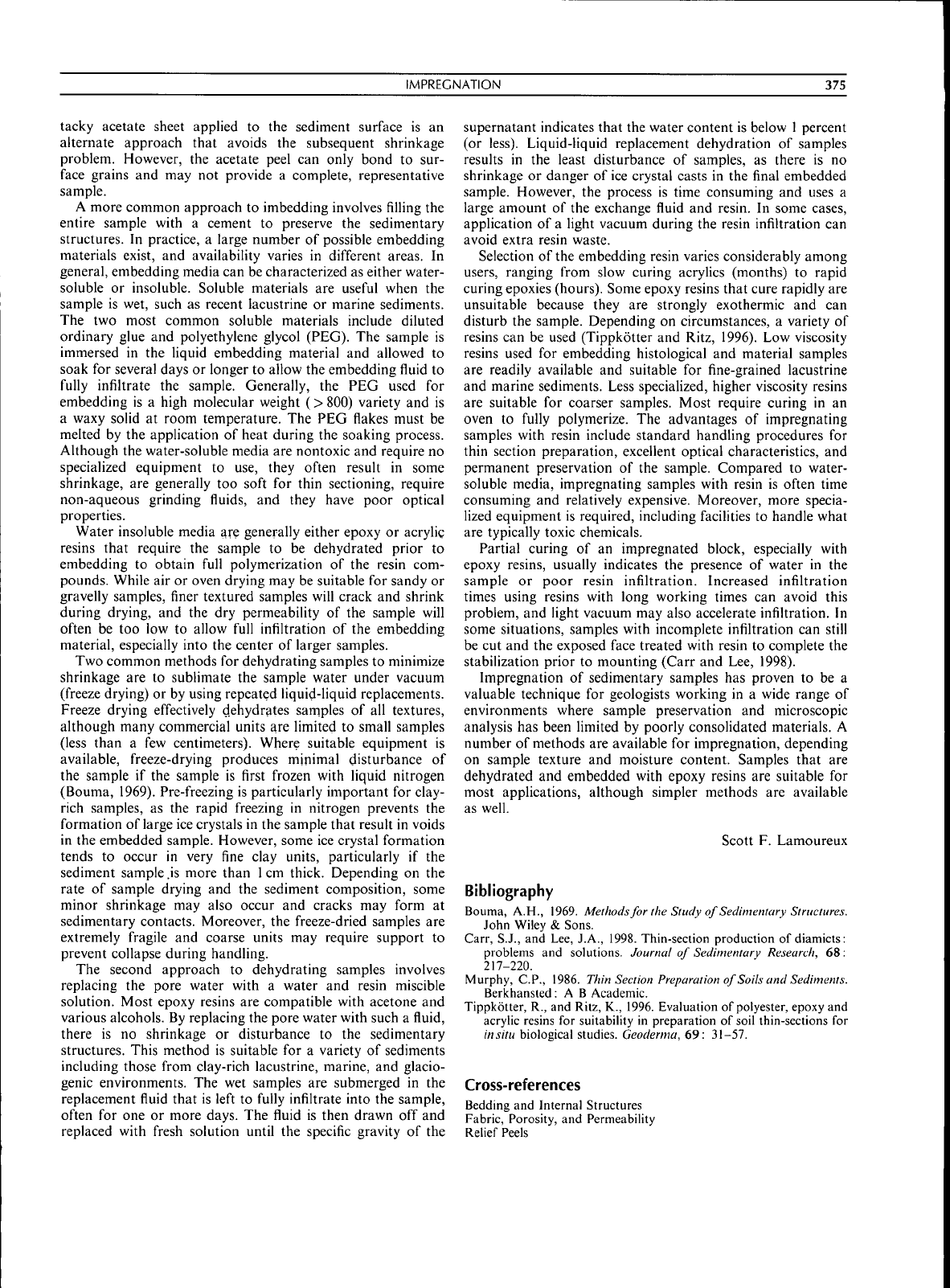

Figure 15 Photographs

of

Pacific seafloor ferromanganese nodules. The upper

p^iir

of

nodules hnve smooth surfaces <ind were collected from

ihe northern cenlral region where sedjmenlalion rates

are

very

low. The

lower pair

of

nodules have granular, botryoidal surfaces and were

collecled from

ihe

northern equatori.il region where sedimentation rates are higher.

IRON-MANGANFSE NODULB 377

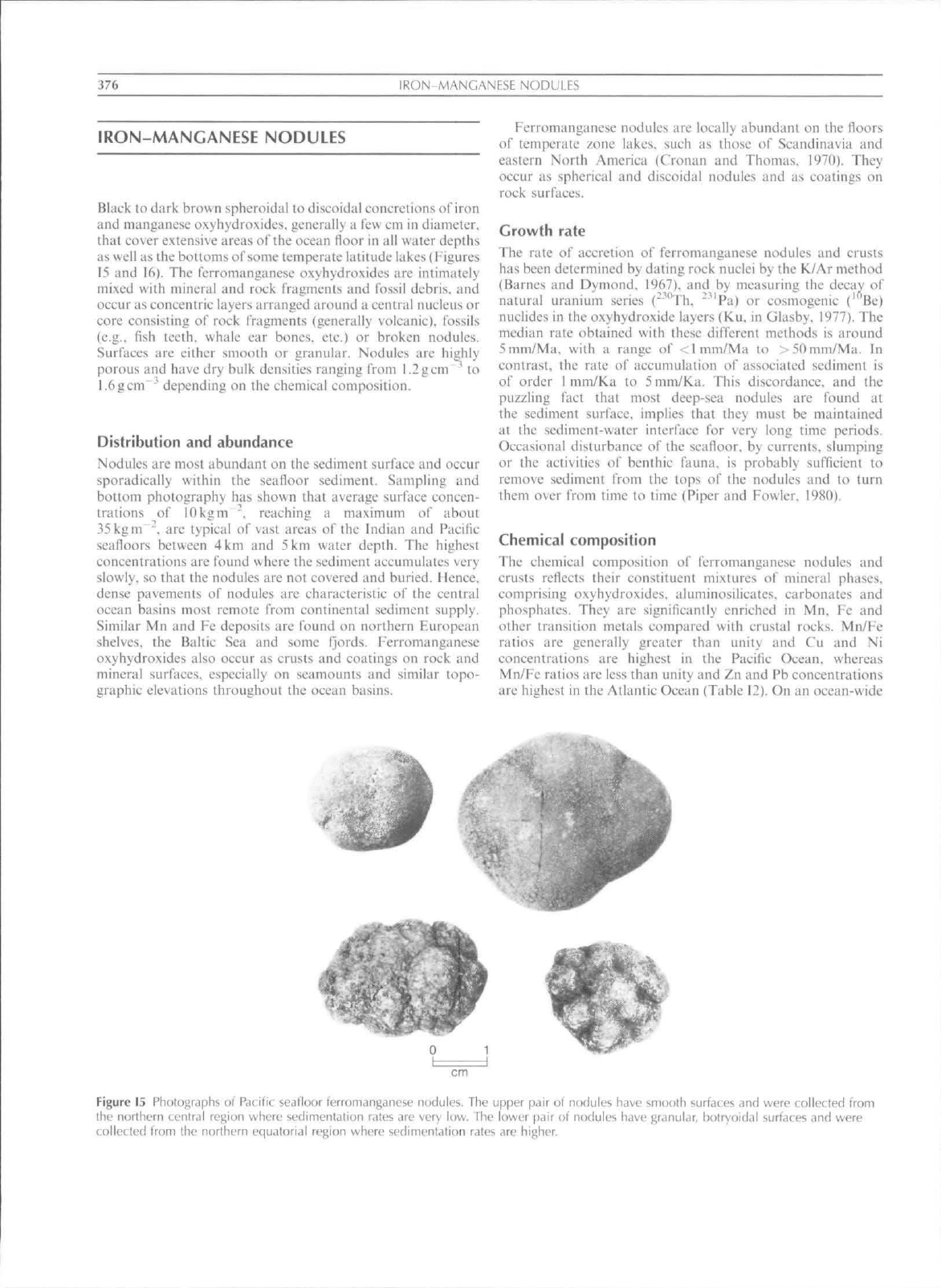

Figure 16 Scal'loor pholograph from the Southern Ocean {81 '

41

S;

1

70' 4O'E; water depth 5160 m) ^howinj; dense pavement ol nodules 2 cm

to ticm in diameter with a li^hl sediment coating. Surface concentration is approximately 25kgm ". Photograph t.iken by S.E. Calvert

using equipment owned by the US Navy,

Table 12 Average chemical composition uf uceanit terromanganese deposits (wt. per cent). From

( ronan (1%0)

Eilenu'iit

Pacific Ocean

Atlantic

Crustal abundance

Mn

Fe

Co

Ni

Cu

Zn

Ph

19.8

12.0

0.33

0.63

0.39

0.07

15.8

20.8

0.32

0.33

0.17

0.08

0,13

0.1

5.6

t).()02

0.007

0,005

0.007

0,001

scale, minor element concentrations appear lo be related to

the Mti or the Fe contents; Ba, Cu. Mo. Ni. and Zn vary

proportionally wilh the Mn conteni, whereas Co. Pb, Ti. and

Ce concentrations correlate with the Fe content. These

relationships reflect the substitution of the minor metals for

Mn or Fe in the tnajor oxyhydroxide mineral phases. Buserite

is a (ibrous tnanjzanate in which a number of divalent cations,

including Mn" ' . Cu, Ni. Zn, etc., substitute for Mn"^' in an

hexagonal array of edge-shared Mn(IV)O(, octahedra thereby

stabilizing the structure (Giovanoli and Arrhenius, in Halbaeb

el

III..

1988); vevniulite is a highly disordered manganate witb

[he approxitnate IbrtnuUi MnO2 which is intimately assoeialed

with ferrihydrite (FeOOH). the principal Fe phase (Burns and

Burns, in Glasby. 1977). MnO^ and F'eOOH host minor tnctals

Ihat can exist in their higher oxidalion states iti the oeean

(Co''.

Pb"^'. Ti"*'. Ce"*"*), but lack sites of the appropriate size

for the substitution of divalent eations. Tbus. buserite is only

Ibiind in nodules with high Mn. Cu. and Ni concentrations,

whereas vernadite oeeurs in nodules with high Fe and Co

eontents. Nodules from shallow water environments eonsist of

a mineral phase similar to buserite. whieh contains very low

minor element contents and is unstable when dried in air

(Calveri and Priee. in Glasby, 1977).

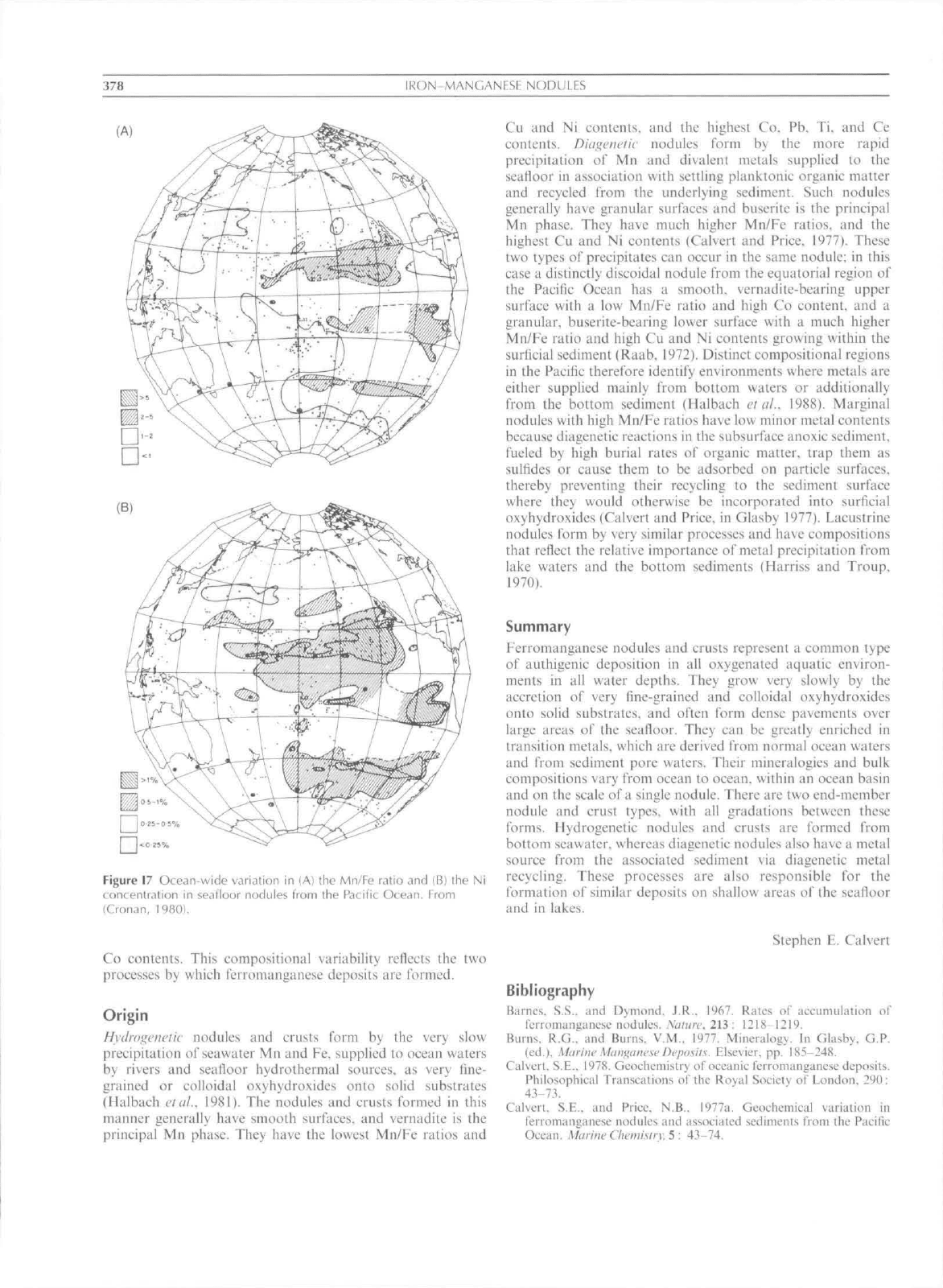

Regional variations

The chemical cotnposilion o^ ferromanganese nodules varies

markedly within a given ocean basin. This is best illustrated in

the Paeitic {Figure 17). where nodules that form in the

marginal areas and in east west zones north and south of

the equator, have the highest Mn/Fe ratios. The abyssal Mn-

rich nodules also have the highest Cu and Ni contents and they

eontain stable buserite as the prineipal Mn mineral phase

(Crotian. 1976; Piper and Williamson. 1977; Calvert. 1978).

The marginal Mn-rich nodules are impoverished in minor

eletnents. and consequently they contain metastable buserite.

Nodules and crusts that form in areas of the seafloor with very

low sedimentation rates and on sediment-starved elevations

abo\e Ihe abyssal seafloor (seamounts and banks) have the

lowest Mn/Fe ratios, they lack buserite and have the highest

378

IRON MANGANESE NODULES

Figure 17 Ocean-wide variation in (Al the Mn/Fe ratio and IB) the Ni

concentration in seal'loor nodules from the Pacific Ocean. From

ICronan,

1980).

Co eontents. This compositional variability reliccts the two

processes by which ferromungiinese deposits are fortned.

Origin

Hydrogciietic nodules and crusts fortn by the very slow

precipitation of seawater Mn and Fe. supplied to ocean waters

by rivers and sealloor hydrothcrmal sources, as very line-

grained or colloidal oxyhydroxides onto sohd substrates

(Halbach el<il.. 1981). The nodules and crusts formed in this

tnanner generally have smooth surfaces, and vernadite is the

principal Mn phase. They have the lowest Mn/Fe ratios and

Cu and Ni contents, and the highest Co. Pb. Ti. and Ce

contents. Diugeiwtic nodules form by the tiiore rapid

precipitation of Mn and divalent metals supplied to the

seatloor in association with settling planktonic organic matter

and recycled from the underlying sediment. Sueh nodules

generally have granular surfaces and buserite is the principal

Mn phase. They have much higher Mn/Fe ratios, and the

highest Cu and Ni contents (Calvert and Priee. 1977). These

two types of precipitates can occur in the satne nodule; in this

case a distinctly discoidal nodule from the equatorial region of

the Pacific Ocean has a smooth, vernadite-bearing upper

surface with a low Mn/Fe ratio and high Co content, and a

granular, buserite-bearing lower surface with a much higher

Mn/Fe ratio and high Cu and Ni contents growing uithiti the

surlicial sediment (Raab, 1972). Distinct cotnpositional regions

in the Pacific therefore identify environments where metals are

either supplied mainly from bottom waters or additionally

from the bottom sediment (Halbach cl iiL. 1988). Marginal

nodules with high Mn/Fc ratios have low tninor metal contents

because diagenetic reactions in the subsurface anoxie scditnent.

fueled by high burial rates oi organic matter, trap them as

sulfides or cause them to be adsorbed on panicle surfaces,

thereby preventing their recycling to the sediment surface

where they would otherwise be incorporated into surlicial

oxyhydroxides (Calvert and Price, in Glasby 1977). Lacustrine

nodules form by very similar processes and have compositions

that reflect the relative importance of metal precipitation from

lake waters and the bottom sediments (Harriss and Troup.

1970).

Summary

Ferromanganese nodules and crusts represent a comtnon type

of authigenic deposition in all oxygenated aquatic environ-

ments in all water depths. They grow very slowly by the

accretion of very fine-grained and colloidal oxyhydroxides

onto solid substrates, and often form dense pavements over

large areas of the seafloor. They can be greatly enriched in

transition metals, which are derived from norrnal ocean waters

and from sediment pore waters. Their tiiineralogies and bulk

compositions vary from ocean to ocean, within an ocean basin

and on the scale of a single nodule. There are two end-member

nodule and crust types, with all gradations between these

forms.

Hydrogenetic nodules and crusts are formed from

bottotn seawater. whereas diagenetic nodules also have a metal

source from the associated sediment via diagenetie metal

reeyeling. These processes are also responsible for the

formation of similar deposits on shallow areas oi the seafloor

and in lakes.

Stephen E. Calvert

Bibliography

ofBarnes. S.S. ;ind Dymond. J.R.. 1967, Rates o\' itccumulatiori

tcrromangiincsc luidttlcs. Nalure. 213: I21K 1219.

Btinis. R.G.. and Burns. V.M.. 1977. Mineralogy. In Glasby. G.P.

(cd.).

Marine SUtn^diicse Deposits.

EISCVILM'.

pp. 185-248.

Calvert. S.E.. 1978. Geochemistry ot oceatiic teiromangatiese deposits.

Philosophical Transcations of the Royal Society of Londoti. 290:

43-73.

CalvLTt. S.E.. and Price. N.B.. 1977a. GcocliL-mical variation irt

lerromanganese tiodtilcs and associated sediments tVotu the Pacific

Oceati, MitriiieClienii.slrv.S: 43-74.

IKONSTONES AND IRON FORMATIONS

379

Ciilvcrt. S.E,. atid Price. N.B.. I977h. Shallow water, contitiental

margin deposits: disirihulioti and geochemistry. In Glasby. G.P.

(ed.).

MaiiiH-

Man^{im-\v

DeptisiiK.

Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 45

86.

Cronan.

D.S,. 1^76, Manjianese tiodtilcs atid other fcrromatigancsc

oxide deposits. In Riley. J.P.. and Chester. R. (eds.). Cliemitul

OceiiiKigrtipliy.

Sati Diego. California: Academic, pp. 217 263.

Cronan.

D.S..

198(1.

Vii<lcn\(ticr Mincnils. Londoti: Academic Press.

362 p.

Cronan.

D.S,. and TliomLis. R.L,. l')7(}, Eerromanganese concretions

in Lake Ontario. Canadiati Jourtiat of Earlh Sciences. 1346-1349.

Giovanoli.

R.. and Arrhenius. G,. I9KS. Structural chemistry oftnarine

manganese and iron minerals and synthetic model compounds. In

Halbach.

P.. (Viedricii, G,. and von Staekelberg. li. (eds,}. The

Munfiauese Ncilule Bell tif ihc Ritiju- Ocean. Stuttgart. Enke,

pp.

2(1

37,

(ilasby. G.P.. (ed,). 1977, Muriiie

Maiiiiaiiesc

Dcpcsil.s.

Elsevier,

Halha'ch.

P,. Enedrich. G,. and von Stackelherg. U.. 1988. TheSUiii-

t-aiiese

Nodule

Belidj

the Faciiic

Ocean.

Stiittuart. Enke. 254 p.

M.ilbacli. P.. Sclierluig. C. Hehlsch. V,, and Marchig. V,. 1981,

Geochemical ant! mineralogical control oj dilterent genetic types oT

deep-sea nodules from the Pacific Oceati: MineruliaDeposiui. 16:

59-84.

Harriss. R,C,. and Troup. A.G,. 1970, Chetnistry and origin of

tVeshuater ferrotnanganese concretions

:

Liiiiiwtagv ciml Oceiiati-

grtiphv . 15: 702 712.

Ku.

T,L,. 1976. Rates of accretion. In Glasby. G.P. (cd.). Mayiue

\ftiii,ii(tiiesi'

Dcpiisii.^.

New York: Elsevier. pp. 249 267.

Piper. D.Z.. iitid Fowler. B. 1980.. New constraint on the iiiaintcnimce

oi"

Mn nodules at the sediment surface

:

.\anirc. 286

:

880-883.

Piper. D.Z.. and Williamson. M.E.. 1977. Regional variations in the

elemental and mineralogical composition of terromanganese

nodules from the pelagic environment of the Pacific Ocean, Mar-

ine Geology. 2i: 285 303.

Raab.

W,. 1972. Physical and chemical features of Pacific deep-sea

manganese

nod tiles

and their implications to the genesis of nodules.

In Hoin. D.R,

(cd.l.

Feyiiimtnigauc.sv Deposits un

ihe

OvcLin

Fttuir.

Washington. DC: National Science I-oiindatioii. pp. 31 49.

Cross-references

Hydro.xidcs and Oxyhydio,\ide Minerals

Oecanic Sediments

IRONSTONES AND IRON FORMATIONS

Iron-rich sedimentary rocks cotitain >15 percetit metallic iron

by weight (James. 1966) utid form a class of chemical

sedimetits comparable to evaporiles and phosphorites. Most

workers recognize two maiti categories. Iron

Formations

are

generally cherty. thinly laminated, and Precambrian in age.

ironstone.s

are generally less siliceous, more aluminous, not

hmiinated,

smaller, and Phanerozoic in age. This distinction

highlights titne-relaled changes whieh constitute one of the

most interesting aspects of iron-rich sedimentary rocks and has

impoitant itnplications for the evolution of Earth's atmo-

sphere and hydrosphere. Both types have long been sources of

iron lor hutnan use. Ironstones wctx' mined in Rotnan limes

and were a key resource in the industrial t'evokttion (Young.

1993). Mineralogical investigations of ironstone began in the

tnid-lSOfls. Studies of iron formations were begun in the late

lSOOs by geologists from the fledgling U.S. Geological Survey

in the Lake Superior region. This work resulted in classic

tiionographs focused oti specific "iron ranges" as well as Van

Hise and Leith (1911). Fresh studies triggered by the demand

for iron during World War [l yielded a new round of U.S.G.S.

publications and the seminal article by James (1954). Large

iron fortiiations and associated deposits of iron ore were still

being discovered. The subsequent discovery and study of large

iron (brmations in Western Australia have been particularly

influential in shaping current percepiions of iron formations,

even though they are exceptional in tnany ways (Trendall,

2002).

The vast majority of iron ihat is ever mined will

be

extracted

from Preeambrian iron formations or derivative deposits.

Large iron formations are eurrently tiiined all over the world.

In

200(1.

Australia produced over 160 tnillion metric tons of

iron ore worth in excess of USS2..'' billion, and China atid

Brazil produced even more. The largest ore deposits occur

where silica was leached and iron was oxidized in iron

formations during the Precatiibrian (Morris. 1987). Ores

produced by post-Precambrian weathering generally have

lower iron contents and more impurities. Iron can also be

extracted from unaltered iron formations by crushing ihem

and separatitig the magtietite.

Iton fortnations have also yielded eeonotnic quatitities ui'

other materials. Iron formations in Archean greenstone belts

host world-class gold deposits, and manganese is extracted in

large quantities from iron formations in Brazil. India, and

especially South Africa. Blue asbestos (erocidolite) was

extracted from iron formations during the mid-[900s. but

production dropped off precipitously as the highly eareino-

genie nature of blue asbestos becatne clear.

iron formations

The main iron minerals fall into four groups which James

(1954) used to define four "facies" of iron fonnation

:

oxide,

silieate, carbonate, and sulfide. In low-gtade iron formations,

the dorninant minerals are magnetite and hematite in the oxide

faeies; greenalite and tiiitinesotaite in the silicate facies: siderite

and ankerite in the carbonate facies: atid pyrite in the sulftde

facies. Where detrita! textures are not obscured by tneta-

morphism. iron formations can be sub-divided into handed

versus granular varieties. Banded iron formations or BIFs.

by far the more abundant of the two. were originally chemical

muds.

Most BIFs exhibit a quasi- to highly rhythtiiie

alternation of layers rich in iron and ehert on a scale of

millimeters to centimeters (Figure IS(A)). Granular iron

fortnations or GIFs originated as well-sorted chetnical sands

(Figure 18(B)) in which the clasts were largely derived via

intrabasinal erosion and redepositioti of pre-existing BIF.

GIFs lack the

even,

continuous banding of BIFs and generally

belong to the oxide or silicate mineral facies. whereas BIFs

show a much broader spectrum of iron minerals, including

a greater abundance of reduced facies (James. 1954; Simonson.

1985). Layers of pure GIF thicker than a few meters are rare,

whereas BIF can continue uninterritpted by GIF for tens to

hundreds of meters stratigr;tphical!y. Iron formations with a

mixture of BIF and GIF are actually more abundant than pure

GIFs,

and they show bedding that is tnore irregular than pure

BIF,

but less massive than pure GIF. In tnixcd iron

formations. GIF takes the form of discontinuous lenses that

probably represent bedforms generated by storm waves and

currents (Simonson. 1985). Chert is not used to classify iron

formalions because it is a ubiquitous eomponeni. but its

abundance helps distitiguish them from ironstoties. Another

380 IRONSTONES AND IRON FORMATIONS

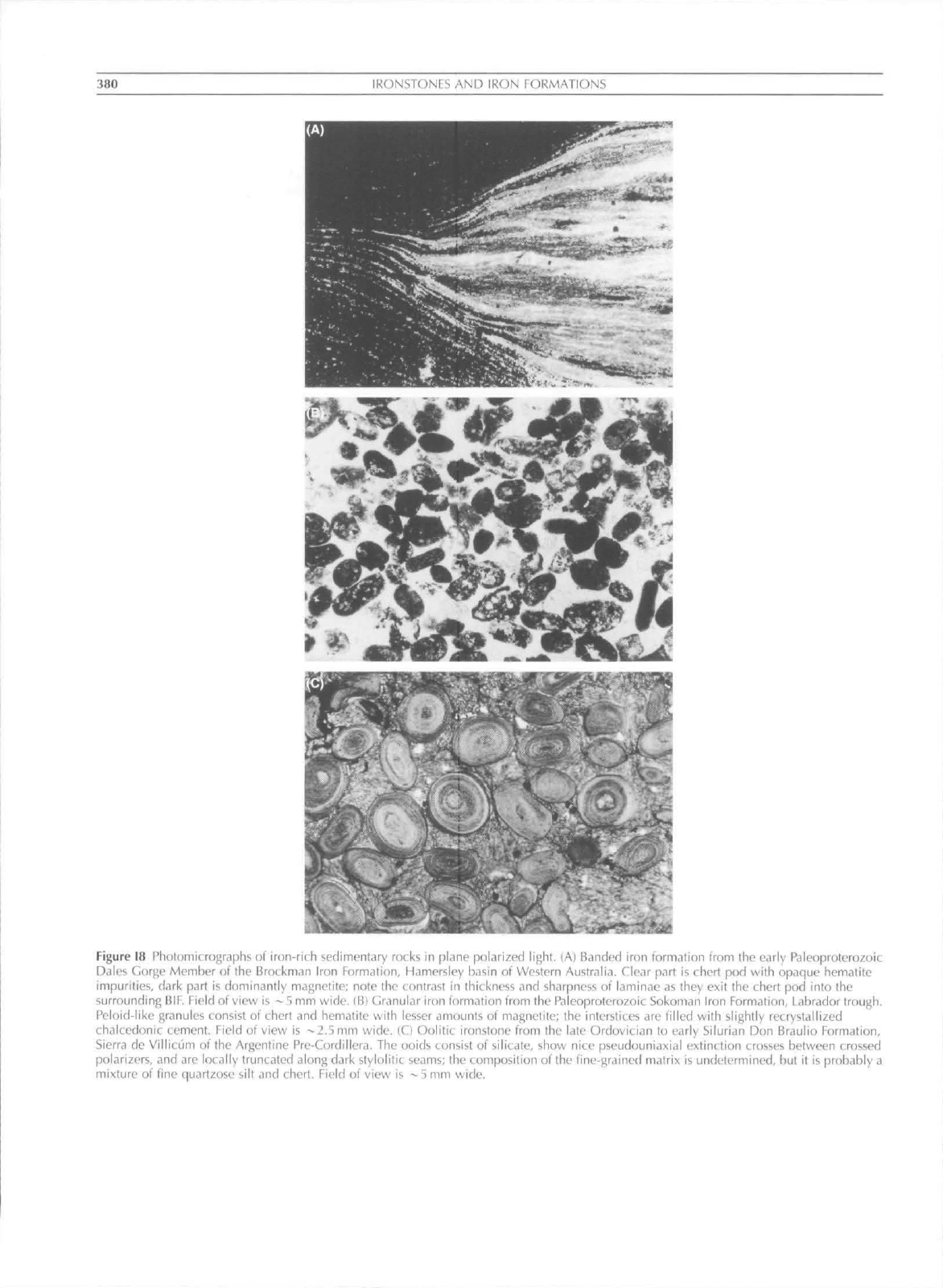

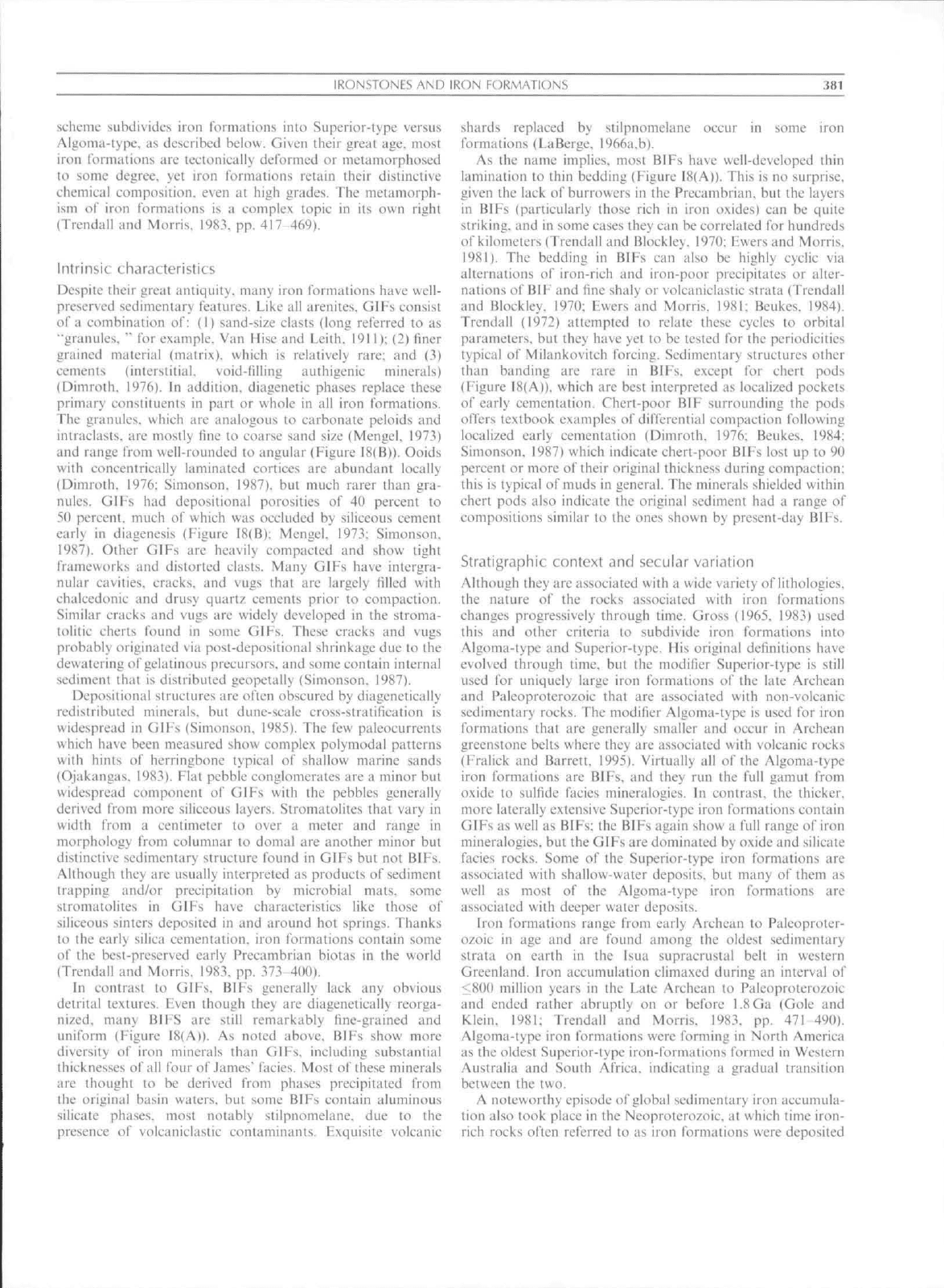

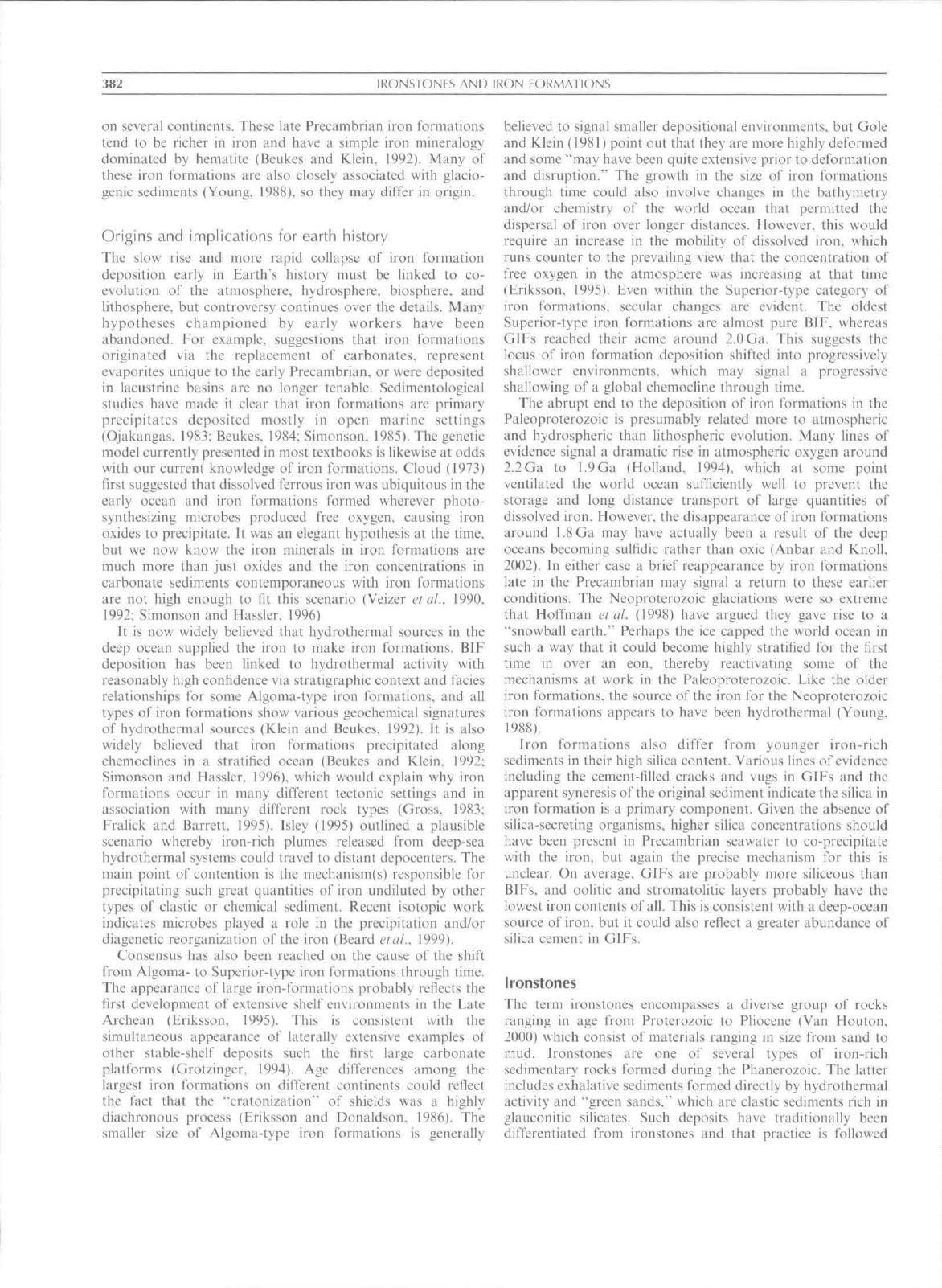

Figure 18 Photomicrographs of iron-rich sedimentary rotks in plane polarized lif>ht. (A) Banded iron lorrtiation from the early Paleoproterozoic

Dales Gorge Memlier of the Brocknian Iron Forrtiation, Hamersley basin of Western Ausiralid. Clear part i5 chert pod with opaque hematite

impurities, riark parl is dominantly magnetite; note the contrast in thickness and sharpness of laminae as ihey exit the chert pod into the

surrounding B!F. Field of view is --5 mm wide. IB) CIranuliir iron formation from ihe Paleoproterozoic Sokoman Iron Formation, Labrador trough.

Peloid-like granules consist of chert and hematite with lesser amounts of magnetite; the interslices are filled with slightly recryslallized

chalcedonic cement. Field of view is -'2.'imm wide. (Cl Oolitic ironstone from the late Ordovician to early Silurian Don Braulio FormtUiun,

Sierra de VJllictJm of the Argentine Pre-Cordillera. The ooids consist of silicate, show nice pseudouniaxial extinction crosses between crossed

polarizers, and are locally truncated along dark styiolitic seams; the composition of the fine-grainetJ matrix is undetermined, but it is probably a

mixture of fine quartzose silt and chert. Field of view is -

5

mm wide.

IRONSTONFS AND IRON FORMATIONS

381

scheme subdivides iron formations into Superior-lype versus

Algoma-type, as described below. Given their great age. most

iron [brmations are tec'tonicaily deformed or rnetatnorphosed

to some degree, yet iron formations retain their distinctive

chemical cotnposition. even at high grades. The metamorph-

istii of iron formations is a complex topic in its own right

(Trendall and Morris, 1983, pp. 417-469).

Intrinsic characteristics

Despite their great antiquity, many iron formations have well-

preserved sedimentary features. Like ail arenites. GIFs consist

of a cotiibination of: (I) satid-size clasts (long referred to as

"granules. " for exatnple. Van Hise and Leith. 191 I): (2) fmer

grained material (matrix), which is relatively rare; and {3)

cetnents (interstitial, void-filling authigenie minerals)

(Dimroth. 1976). In addition, diagenetic phases replace these

primary constituents in part or whole in all iron formations.

The granules, which are analogous to carbonate peloids and

intraelasts. are mostly fine to coarse sand size (Metigel. 1973)

and range from well-rounded to angular (Figure I8(B)). Ooids

with concentrically laminated cortices are abundant locally

(Diniroth. 1976: Simonson. 1987). but much rarer than gra-

nules.

GIF's had depositional porosities of 40 percent to

50 percent, much o\' which was occluded by siliceous cement

early in diagenesis (Figure I8(B); Mengel, 1973; Simonson.

1987).

Other GIFs are heavily compacted and show tight

frameworks and distorted clasts. Many GIFs have intergra-

nular cavities, cracks, and vugs that are largely filled with

chalcedonic and drusy quartz cetnents prior to compaction.

Similar cracks and vugs arc widely developed in the strotna-

loiitic cherts found in some GIFs. These cracks and vugs

probably (triginated via post-depositional shrinkage due to the

dewatering of gelatinous precursors, and sotne contain internal

seditnent that is distributed geopetally (Simonson. 1987).

Depositional stritetures are often obscured by diagenetically

redistribitted minerals, but dunc-scaie cross-stratification is

widespread in (ilFs (Sitiionson. 19S5). The few paleocurrents

which have been measured show complex polymodal patterns

with hints of herringbone typical of shallow marine sands

(Ojakangas. 1983). Flat pebble conglomerates are a minor but

widespread component of GIFs with the pebbles generally

derived from more siliceous layers. Stromatolites that vary in

width from a centimeter to over a meter and range in

morphology frotn columnar to domal are another tninor but

distincti\e sedimentary structure found in GIFs but not BIFs.

Although they are usually interpreted as products of seditnent

trapping and/or precipitation by microbial mats, some

stromatolites in GIFs have characteristics like those of

siliceous sinters deposited in and around hot springs. Thanks

to the early silica cementation, iron formations contain some

o\'

the best-preserved early Precambrian biotas in the world

(Ttctidall and Morris. 1983, pp. 373-400).

In contrast to GIFs. BIFs generally lack any obvious

detrital textures. Fven though they are diagenetically reorga-

nized, tnany Bil-"S are still retnarkably iine-grained and

unitbrtn (Figure I8(A)). As noted above. BIFs show more

diversity oi' iron minerals than GIFs, including substantial

thicknesses ol'all four of James' facies. Most of these minerals

are thought to be derived from phases precipitated from

the original basin waters, but some BIFs eontain aluminous

silicate phases, most notably stilpnomelane. due to the

presence of volcaniclastic contaminants. Exquisite volcanic

shards replaced by stilpnomelane occur in some iron

formations (LaBerge, 1966a.b).

.As the name itnplies. most BIFs have well-developed thin

latninaiion lo thin bedding (Figure 18(A)). This is no surprise,

given the lack oi' burrowcrs in the Precambrian. but the layers

in BIFs (particularly those rich in iron oxides) can be quite

striking, and in sotne cases they can be correlaled for hundreds

of kilometers (Trendall and Blockley. 1970; Ewers and Morris,

1981).

The bedding in BIFs can also be highly cyclic via

alternations of iron-rieh and iron-poor precipitates or alter-

nations of BIF and fine shaly or volcaniclastic strata (Trendall

and Blockley. 1970; Ewers and Morris. 1981; Beukes. 1984).

Trendall (1972) attempted to relate these cycles to orbital

parameters, but they have yet to be tested for the periodicities

typical of Milankovitch forcing. Sedimentary structures other

than banding are rare in BIFs, except for chert pods

(F'igure I8(A)). whieh are best interpreted as localized pockets

of early cementation. Chert-poor BIF surrounding the pods

offers textbook examples of differential compaction following

localized early cementation (Dimroth. 1976; Beukes, 1984;

Simonson. 1987) which indicate chert-poor BIE-'s lost up to 90

percent or more of their original thickness during cotnpaction:

this is typical of muds in general. The tninerals shielded within

chert pods also indicate the origitial sediment had a range of

compositions similar to the ones shown by present-day BIFs.

Stratigraphic context and secular variation

Although they are associated with a wide variety of lithologies.

the nature of the rocks associated with iron formations

changes progressively through time. Gross (1965. 1983) used

this and other criteria lo subdivide iron formations into

Algoma-type and Superior-type. His original definitions have

evolved through time, but the modifier Superior-type is still

used for uniquely large iron formations of the late Arehean

and Paleoproterozoie that are associated with non-volcanic

sedimentary rocks. The modifier Algoma-typc is used for iron

formations that are generally smaller and occur in Archean

greenstone belts where they are associated with volcanic rocks

(Fralick and Barrett. 1995). Virtually all of the Algoma-type

iron formations are BIFs, and they run the full gamut from

oxide to sulfide facies mineralogies. In contrast, the thicker,

more laterally extensive Superior-type iron formations contain

GIFs as well as BIFs; the BIFs again show a full range of iron

mineralogies, but the GIFs aredotninated by oxide and silicate

facies rocks. Some of the Superior-type iron formations are

associated with shallow*water deposits, but many of them as

well as most of the Algoma-type iron formations are

associated with deeper water deposits.

Iron formations range from early Archean to Paleoproter-

ozoic in age and are found among the oldest sedimentary

strata on earth in the Isua supracrustal belt in western

Greenland. Iron accumulation clitnaxed during an interval of

<80(l million years in the Late Archean to Paleoptoicro/oic

and ended rather abruptly on or before 1.8Ga (Gole and

Klein. 1981; Trendal! and Morris. 1983. pp. 471 490).

Algoma-type iron fortnations were forming in North America

as the oldest Superior-type iron-formations formed in Western

Australia and South Africa, indicating a gradual transition

between the two.

A noteworthy episode of global sedimentary iron accumula-

tion also took place in the Neoproterozoic. at which time iron-

rich rocks often referred to as iron formations were deposited

382

IRONSTONES AND IRON FORMATIONS

on several continents. These late Precambrian iron fortnations

tend to be richer in iron and have a simple iron mineralogy

dominated by hematite (Beukes and Klein, 1992). Many of

these iron formations are also closely associated with glacio-

genic sediments (Young. 1988), so they may differ in origin.

Origins

and

implicafions

for

earth history

The slow rise and more rapid collapse of iron formation

deposition early in Earth's history must be linked to co-

e\olution of the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and

lithosphere. but controversy continues over the details. Many

hypotheses championed by early workers have been

abandoned. For example, suggestions that Iron formations

originated via the replacetnent of carbonates, represent

evaporites unique to the early Precambrian. or were deposited

in lacustrine basins are no longer tenable. Sedimentological

studies have made it clear that iron formations are primary

precipitates deposited mostly in open marine settings

(Ojakangas. 1983; Beukes, 1984; Simonson, 1985). The genetic

model curtently ptesented in tnost textbooks is likewise at odds

with otir current knowledge of iron fortnations. Cloud (1973)

first suggested thai dissolved ferrous iron was ubiquitous in the

early ocean and iron fortnations formed wherever photo-

synthesizing microbes produced free oxygen, causing iron

oxides to precipitate. It was an elegant hypothesis at the time.

but we now know the iron minerals in iron formations are

much more than jusf oxides and the iron concentrations in

carbonate sediments contemporaneous with iron formations

are not high enough to fit this scenario (Veizer cl uL. 1990,

1992;

Simonson and Hassier. 1996)

It is now widely believed that hydrothermal sources in the

deep ocean supplied the iron to make iron formations. BIF

deposition has been linked to hydrothermal activity with

reasonably high confidence via strafigraphic context and facies

relationships for some Algoma-type iron formations, and all

types of iron formations show various geochemical signatttres

of hydrothcrmal sources (Klein and Beukes, 1992). It is also

widely believed that iron formations precipitated along

chetnoclines in a stratified ocean (Beukes and Klein. 1992;

Sitnonson and Hassier, 1996), which would e.xpiain why iron

formations occur in many different teefonic settings and in

association with many difierent rock types (Gross, 1983;

Fralick and Barrett, 1995). Isley (1995) outlined a plausible

scenario whereby iron-rich plumes released from deep-sea

hydrothermal systems could travel to distant depocenters. The

main point of contention is the mechanism(s) responsible for

precipitating such great quantities of iron undiluted by other

types of clastic or chemical sediment. Recent isotopic work

indicates microbes played a role in the precipitation and/or

diagenetic reorganization of the iron (Beard eial.. 1999).

Consensus has also been reached on the cause of the shift

from Algoma- to Superior-type iron formations through time.

The appearance of large iron-formations probably reflects the

first developtnent of extensive shelf environmetits in the Late

Archean (Eriksson. 1995). This is consistent with the

simultaneous appearance of laterally extensive exatnples of

other stable-shelf deposits such the first large carbonate

platforms (Grotzinger, 1994). Age differences among the

largest iron formations on different continents could reflect

the fact that the "cratonization" of shields was a highly

diachronous process (Eriksson and Donaldson. 1986). The

smaller size of Algoma-type iron formations is generally

believed to signal smaller depositional environtnents, but Gole

and Klein (1981) point out thai they are more highly deformed

and some "may have been quite extensive prior to deformation

and disruption." The growth in the size of iron formations

through time cottld also involve changes in the bathymetry

and/or chemistry of the world ocean that permitted the

dispersal of iron over longer distances. However, this would

require an increase in the tnobility of dissolved

iron,

which

runs counter to the prevailing view that the concentration of

free oxygen in the atmosphere was increasing at that time

(Eriksson, 1995). Even within the Superior-type category of

iron lbrmations. secular changes are evident. The oldest

Superior-type iron fortnations are almost pure BIF. whereas

GIF's reached their acme around 2.0Ga. This suggests the

locus of iron formation deposition shifted into progressively

shallower environments, which may signal a progressive

shallowing of a global chemocline through time.

The abrupt end to the deposition of iron formations in the

Paleoproterozoic is presumably related more to atmospheric

and hydrospheric than lithospheric evolution. Many lines of

evidence signal a dramatic rise in atmospheric oxygen around

2.2Ga to !.9Ga (Hollatid. 1994). which at sotne point

ventilated the world ocean sufftciently well to prevent the

storage and long distance transport of large quantities of

dissolved

iron.

However, the disappearance of iron formations

around 1.8Ga may have actually been a result of the deep

oceans becoming sulfidic rather than oxic (Anbar and Knoll,

2002). In either case a brief reappearance by iron formations

late in the Precambrian tnay signal a return to these earlier

conditions. The Neoproterozoic glaciations were so extretne

that Hoffman elal. (1998) have argued they gave rise to a

"snowball earth." Perhaps the ice capped the world ocean in

such a way that it could become highly stratified for the lirst

time in over an eon, thereby reactivating some of the

mechanisms at work in the Paleoproterozoic. Like the older

iron formations, the source of the iron for the Neoproterozoic

iron formations appears to have been hydrothermal (Young.

1988).

Iron formalions also differ frotn younger iron-rich

sediments in their high silica content. Various lines of evidence

including the cement-filled cracks and vugs in GIFs and the

apparent syneresis of the original sediment indicate the silica in

iron formation is a primary component. Given the absence of

silica-secreting organisms, higher silica concentrations should

have been present in Precambrian seawater to co-precipitatc

with the

iron,

but again the precise tnechanism for this is

unclear. On average. GIFs are probably tnorc siliceous than

BIFs.

and oolitic and stromatolitic layers probably have the

lowest iron contents of

all.

This is consistent with a deep-ocean

source of

iron,

but it could also reflect a greater abundance of

silica cement in GIFs.

Ironstones

The tenn ironstones encompasses a diverse group of rocks

ranging in age from Protcrozoic to Pliocene (Van Houton.

2000) which consist of materials ranging in size from sand to

mud.

Ironstones are one of several types of iron-rich

sedimentary rocks formed during the Phanerozoic. The latter

includes exhalativc sediments formed directly by hydrothermal

activity and "green sands." which are clastic seditncnts rich in

glauconitic silicates. Such deposits have traditionally been

differentiated from ironstones and that practice is followed

IRONSTONES AND IRON FORMATIONS

383

here,

even though glauconitic sediments and ironstones have

much in common (Van Houton and Purucker, 1984; Odin,

1988). Given their young geologic age. ironstones are much

less likely to be deformed or metamorphosed than iron

fortnations and comtnonly contain fossil debris. This has

permitted detailed analyzes of the depositional setting of

iron-

stoties

(e.g..

Hunter, 1970; Van Houton and Bhattacharyya.

1982). bitt consensus on the specific mechanisms and timing of

iron precipitation has retnained elusive.

Intrinsic characteristics

Ironstones cotitain representatives of all four of James" (1954)

tnineral facies. but differ from iron formations in some ways.

Most ironstones consist of oxides and/or silicates, although

siderite is also common in some (Odin. 1988). This is similar to

the assemblages found in GIFs, but more oxidized than iron

formations as a whole, given the widespread occurrence of

reduced facies in BIFs. The oxides and silicates found in

ironstones versus iron formations also differ systematically.

Hetnatite is found in both, but gocthitc is only comnmn in

ironstones whereas magnetite is only common in iron

fortnations. Likewise, chamosite and berthierine arc the chief

iron-rich silicates in ironstones but rare in iron formations. In

addition to iron-rich phases, ironstones typically contain

quartz sand, calcite, dolomite, and authigenic phosphorite

and chert. All of these phases are rare in iron formations with

the exception of chert. These tnineralogical differences arc

retlecJed in lower iron and silica and higher alutnina contents

in ironstone versus iron fonnation. which is partly, but not

entirely, a rellection of the age disparity between the two (sec

belov\).

Ooids arc a distinctive feature of many ironstones

(Figure 18(C)). but they are rarely its main constituent. Like

those in iron formations, the ooids in ironstones consist of

a nucleus plus a cortex with thin concentric laminations; no

radial textures have been reported from ooids in cither iron

formations or ironstones. Ironstone ooids consist of iron

silicates and/or iron oxides: these two minerals occur in

alternating laminae in some ooids. The nuici of the ooids are

diverse in composition, rangitig from calcareous fossil debris

to detrital quartz sand grains to fragments of oolitie cortices.

Replacetnent textures are commonly observed in the ooids.

involving both iron-rich and iron-poor materials (including

fossils) as both replacer and rcplacee. Despite the attention

lavished on the ooids, other constituents probably form the

bulk of ironstones. One common constituent is interstitial

calcite or dolomite ccmcnl. but the most abundant arc

probably fitiely crystalline iron oxides, iron-rich silicates, and/

or siderite. Much of this finer tnaterial is authigenic rather than

detrital in origin (Odin. 1988). Many oolitic ironstones are

cross-bedded, a sure sign they originated as well-sorted sands,

but other ironstones are highly bioturbated. and show evidence

of hardground-like induration in the form of local sediment

reworked as intraelasts (Odin. 19S8).

Strafigraphic context

and

secular variation

Most oolitic ironstones take the form of thin interbeds amidst

successions of clastic and carbonate strata deposited in shallow

marine environments. These are typically sediments deposited

close to paleoeoastlines in water on the order of a few tens of

meters deep. In general., ironstones are Ibrmed closer to shore

and in shallower water than time-equivalent glaueonitic

deposits

(e.g..

Hunter. 1970). but the abundant remains of

nonnal marine organisms and the evidence of repeated

reworking indicate ironstones accumulated on the open

sealloor rather than in restricted settings. Nevertheless, most

workers believe ironstones did not accumulate in the highest

energy environments, which is consistent with their common

association with clastic mudroeks. Ironstones also tend to

occur at stratigraphic breaks which coincide with trans-

gressions (Van Houton and Bhattacharyya, 1982). Essentially,

ironstones are now believed to constitute condensed sequences

formed largely during times of ma.ximum transgression and

reduced clastic inllux. This is also true oti a grander scale: the

two tnain pulses of ironstone accutnulation coincide with

Fischer's two '"greenhouse" phases of sea-level highstand frotn

the Ordovician to the Devonian and from the Jurassic to the

Paleogene (Van Houton and Arthur, 1989).

Ironstones also vary in mineralogical composition as a

function of age. Goethite and berthierine are both relatively

comtnon in the Mcsozoic to Tertiary ironstones, whereas

hematite and chamosite dotninate the Paleozoic ironstones.

This contrast probably reflects a higher degree of diagenetic

equilibration by the older ironstones.

Origins

and

implicafions

for

earfh history

The fundamental problem in the origin of ironstones is

reconciling the evidence for deposition under open-marine,

oxidizing conditions with the fact thai dissolved iron is only

mobile under reducing conditions (Odin. 1988). This leaves

three options: (I) ironstones were originally deposited as

something entirely different and replaced by iron-rich phases

after burial: (2) conditions fluctuated between oxidizing and

reducing during deposition; or (3) high concentrations of iron

somehow managed lo accumulate under oxidizing conditions.

Sotne of the earliest in\cstigators took the presence of ooids in

ironstones to mean that they were diagcneticalK replaced

carbonates. Fven though carbonate fossils are locally replaced

by iron-rich minerals, this interpretation has fallen out of favor

due to the evidence of synseditnentary reworking of various

types of ironstone and the apparent lack of any units of

carbonate oolite that are half-converted to oolitic ironstone.

Faced with a lack of sedimentological evidence for bottom

water anoxia during deposition, most workers now envision

ironstones as forming under a fully oxidized water column.

This is clearly happening today in the case of glauconitic

sediments (Van Houton and Purucker. 1984). and thin oolitic

coatings of chamosite have been reported from pellets on the

modern seafloor at one site (Rohrlich etal... 1969). The latter

are well below wave base, which suggests the coatings may be

able to grow in .situ without benclit of regular physical

movement. Some researchers have even proposed the ooids

originated entirely in siiu. but the widespread breakage and

regrowth of the ooids argue against this. Other workers have

suggested they are pedogenic ooids that were transported then

redcposited on the seafloor, but the highly concentrated nature

of ironstones and their stratigraphic context makes this seem

highly unlikely also. The current thinking is that ironstones

originally accumulated mainly as ferric materials, then were

modified considerably via early diagenetic authigencsis of the

iron-rich phases very close to the sediment water interf^ice

(Odin,

1988).

384

IRONSTONES AND IRON FORMATIONS

In summary, ironstones can probably originate in different

ways,

but mosf formed more or less where they were ultimately

buried via a process of slow iron precipitation during times

of highly reduced seditnentation rates. Proximity to a river

mouth is also thought to be advantageous because the source

of the iron is generally attributed to deep weathering on

adjacent landmasses. However, this is somewhat at odds with

the temporal correlation of ironstone and black shale

deposition (Van Houton and Arthur. 1989). Whatever the

source of the iron and the mechanism of deposition, both the

iron-rich and iron-poor phases in ironstones were clearly

affected by a host of early diagenetic transformations; many

took place so close to the sediment/walcr interface that new

phases were detritally reworked. In conclusion, the separation

of iron formations and ironstones into two separate categories

seems to be quite justifiable, but a closer comparison between

these two might be very instructive in terms of revealing what

processes were taking place on or near the early Precambrian

seafloor.

Bruce M. Simonson

Bibliography

Aiihar. A.D., iiiid Knoll. A.H..

21J02.

Proterozoic ocean chemistry

and

evolution:

A

hioirtoryanic hridge?

Science.

297

:

11.^7 -1192.

Beard.

B.L..

Johnson.

CM.. Cox. L., Sun. H..

Nealsoti.

K.H.. and

Agtiitar,

C. 1999.

Iron isotope biosienatures.

.Science.

285:

1889

1892.

Beukes.

N.J..

1984. Sedimentology

of the

Kuruman atid Griquatown

Iron-formations. Transvaal Stipcrgroap. Griquakind West. SoiHh

Africa.

Precimthrktn

Reseurch.

24:

47-84.

Beukes,

N.J.. and

Klein.

C. 1992.

Models

for

iron-formalion

deposition.

In

Schopf,

J.W.. ;ind

Klein.

C

(eds.).

The Prolerozoie

Biiisphere.

.-)

Mitllitlisciplinarv

Situly.

Cambridge University Press.

pp.

147-151.

Cloud.

P.. 1973.

Paleoecological signiticiincc

of the

banded

iron-

formalion.

Economic Geoliifry.

68: 1135 1143.

Dimroth,

E.,

1976. Aspects

of

the

sedimentary petrology

of

eherly iroti

formation.

In

Wolf.

K.H.

(ed.), Hantlhook

cj

Siratu-Botind itnd

Slniliffirm

Ore

Depo.siis,

7.

Elsevier.

pp. 203 254.

Eriksson.

K.A.. 1995.

Crustal giowtli. surface processes

and

alnio-

spheric evolution

of the

eiirly Earth.

In

Coward,

M.P.. and

Ries.

A.C.

(eds.), Etirly

Precunihriun

Processes.

Geological .Society

of London. Special Puhlictttion,

95. pp.

11

-25.

Eriksson.

K.A..

atid Dotialdson.

J.A. 1986.

Basin;tl aitd shelf

sedimentation

in

reiaiion

to the

Archaean-Prolerozoic boundary.

Preccimhniin

Reseairh.

33:

103-121.

Ewers.

W.E.,

atid Morris.

R.C.. 1981.

Studies

of the

Dales Gorge

Member

of the

Brockman Iron Fortnation. Western Aiistralia.

EeonomicGeology.

76:

1929-1953.

Fralick.

P.W.. and

Barrett.

T.J., 1995.

Depositional controls

on

iron fortnalion associations

in

Canada.

In

Plint.

A.G.

(ed.),

Seclimeiiiiiry

Em ies

Analysis. Internatiomil Association

of

Sedimentologisi, Special Publication,

22. pp. 137 156.

Gole.

M.J.. and

Klein.

C. 1981.

Banded iron-formations through

much

ol'

Pieeambrian time, .louvnal of

Geology.

89

:

!69 183.

Gross.

G.A..

1965.

Geology of Iron Depositsoj

Ciinuda.ihlunie

I.

General

GeologyundEnilualionaflron

Deposits.

Ottawa: Geological Survey

of Canada. Economic Geology. Report

22.

Gross.

G.A., 1983.

Tectonic systems

and the

deposition

of

iron-

formation.

Preitnnhyiein

Reseiireh.

20:

171-187.

Grotzinger.

J.P.. 1994.

Trends

in

Precambrian carbonate sediments

and their implications

lor

undetstanding evolution.

In

Bcngsion.

S.

(ed.).

Early Li/eon

Eitrlh.

Nobel

Symposiiii)i,S4.

Columbia Ihiiversity

Press,

pp.

245-25S.

Hoffman.

P.F..

Kaufman.

A.J..

Ilalverson.

CJ.P..

and

Schrag.

D.P..

1998.

A

Neoprolero/oic snowball earth.

.Seieiiee.

281

:

1.342-1.346.

Holland.

H.D.. 1994.

Early Proierozoic atmospheric change.

In

Bengston.

S.

(ed.). Early Life

on

Eurlh.

Nobel Symposium

No.

S4.

Columbia University Press,

pp. 237 244.

Hunter.

R.E.. 1970.

Facies

of

iron sedimentation

in ihe

Clinton

Group.

In

Fisher.

G.W..

Pettijolin.

F.J..

Reed.

J.C. Jr.. and

Weaver,

K.N.

(eds.).

Siiulies

of

Appalaehian

Geology:

Cenlnilanil

Southern.

Wiley,

pp. iOl 124.

Isley,

A.E.. 1995.

Hvdrothermal plumes

and

tlie delivery

of

iron

lo

banded iron fortnalion. Jourmil of

Geology.

103:

169-185.

James.

H.L., 1954.

Sedimentary facies

of

iron-formalion. Economic

Geology.

49: 235 293.

James.

H.L.. 1966.

Chemistry

of the

Iron-Rich Sedimentary Rocks.

L^nileil

Slates Geological Survey Professional Paper

440-W.

l.aBerge.

G.L..

I96(ia. Altered pyroclastic rocks

in

iron-formation

in

the MamerslL-y Range, Western Australia.

Economic

Geology.

61 :

147-161.

LaBerge.

G.L..

1966b. Pyroclaslic rocks

in

South African

iron-

formations.

£•((»((»»«•

Ctvi/(',t,'r. 61

: 572 581.

Klein.

C. and

Beukes.

N.J.. 1992.

Proterozoie iron fortnations.

In Condic.

K.C.

(ed.).

Prolerozoie

Crusia! Evolution. Elsevier.

pp.

383 418.

Mengel,

J.T., 1973.

Physical sedimentation

in

Precatnbrian cherty

iron fomiaiions

of the

Lake Superior type.

In

Amstutz,

G.C..

and Bernard.

A.J.

(eds.). Ores

in

Sedintfiits. Springer-Verlag,

pp.

179 193.

Morris.

R.C.. 1987.

Iron ores derived

by

enrichment

of

banded

iroti-

formation.

In

Hein.

J.R.

(ed.).

Siliceous Sedimentary Rock-hosled

Ores and

Pelroleiini.

Van

Nostrand Reinhold

Co.. pp.

231

267.

Odin.

G.S.

(ed.).

19H8.

Green Marine Clays. Developments

in

Seditnentology

45.

Elsevier.

Ojakangas.

R W..

1983.

Tidal deposits

in

the early Protero/oic basiti

of

the Lake Superior region tlie Palms and Pokegama I-ormaiions:

evidence

for

subtidal shelf deposition

of

Superior-type banded

iron-formation.

In

Medaris.

L.G. Jr.

(ed.). Early Proteroroic

Geology

of

the Great Eakes

Region.

Geological Socieiy

of

Atnerica

Memoir.

60. pp. 49 66.

Rohrlicli.

V,.

Price.

N.B . and

Calveri.

S.H., 1969.

Chaniosiie

in

tlie

Recen!

scdimenls

of

Loch Etive. Scotland.

Journal

of Sedimentary

Petrology.

39: 624 631.

Simonson.

B.M..

1985. Sedimentoiogieai constraints

on ihe

origins

of

Precambrian iron-i'ormiitions. Geological Society

of

Amereriai

Bulletin.

96:

244-252.

Sitnonson.

B.M., 1987.

Early silica cementation

and

subsequent

diagenesis

in

arenites from four early Proterozoie iron forma-

tions

ol"

Nortli America. Jotirnal

of

Sedimentary

Petrology.

57:

494

511.

Simonson.

B.M.. and

Hassier.

S.W..

1996. Was the depositioti oflarge

Precambrian iron fortnations linked

to

major marine trans-

gression.'

Journal oj

Geology.

104: 665 676.

Trendall.

A.F.. 1972.

Revolution

in

earth history. Journal

t)f

the

Geological Society

ojAuslralia. 19

:

287-31!.

Trendall.

A.F..

2002.

The

significance

of

iron-form at ion

in the

Precambrian stratigraphic record.

In

Altermann.

W.. and

Corcoran.

P.L.

(eds.). Precanthrian Sedimentary Environments:

A Modern

Approach

to

Ancient

Deposilional

.Systems.

International

Association

of

Sedimeniolosiists. Special Piiblicatiim.

33. pp.

33

66.

Trendall.

A.F.. and

Blockley.

J.G.. 1970. The

lion Formations

of

the Precambrian Hamersley Group. Western Australia. Perth:

Geological Survey

oji{['.\lern

.Australia

Bulletin.

119.

Trendall.

A.F.. and

Morris.

R.C.

(eds.).

1983.

Iron-Formaiion. Facts

and

Prohlems.

Elsevier.

Van Misc.

C.R.. and

Leith,

C.K..

1911.

Geology

of

the Lake Superior

Region.

United Slates Geological Survey Monograph

52.

Van Houton.

F\B.,

2000. Ooidal ironstones

and

phosphorites—a

comparison from

a

stratigraplier's view.

In

Glenn.

C.R..

Prevol-

Lucas.

L . and

Lucas. J. (eds.).

Marine

Authigenesis:

FrontGlohalto

Mierobial. Society

of

Economic Paleontologists

and

Mineralogists.

Special Publication. 44.

pp. 79 106.

Van Houton.

F.B.. and

Arthur.

M.A.. 1989.

Temporal patterns

among Phanerozoic oolitic ironslones

and

oceanic anoxia.

In

Young.

T.P.. and

Taylor. W.E.G. (eds.).

Phanerozoic

Ironslones.

Geoloiiical Society

of

London, Special Publication,

46, pp.