Mattingly J.D., Heiser W.H., Pratt D.T. Aircraft Engine Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

,,,=

==

==

==

=1

¢,

o~

¢-q

~o~

I-

~ I ~ I,~ _

I ~1

I I I I~1 I I i~r i i f~l f i]~ ~ . .._, ~

,._=

I I I I~1 I I I~1 I I I~1 I I I,~

I I I I~1 I I I~-I I I I~1 I I I~-I~

ddddddddddddddddddddddd

E

E

2

;=

,..5

~=

$

H

..j

E

b

182

Fuel

Saved

(lbf~

ENGINE SELECTION: PERFORMANCE CYCLE ANALYSIS 183

300

200

100

-100

-200

20

J

21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

Compressor Pressure Ratio (~c)

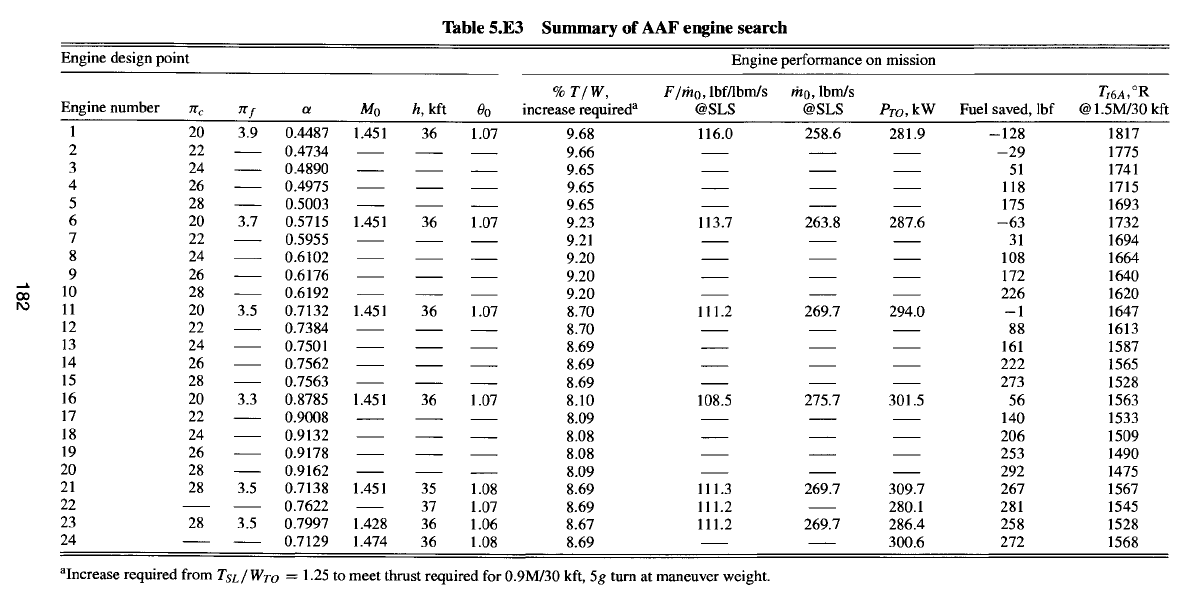

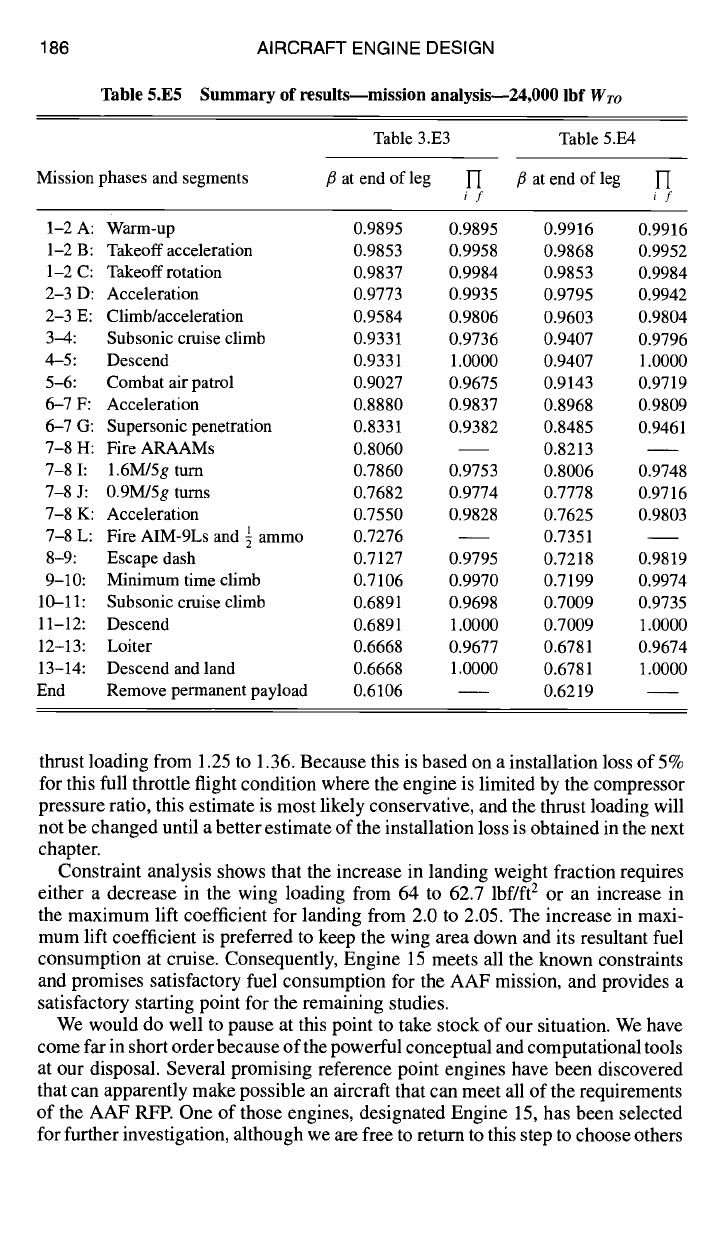

Fig. 5.E3 Fuel saved referenced to Wr = 6690 lbf.

performance results. Unfortunately, as we have come to expect, the reverse is true

for the specific thrust.

The fuel saved for these engines is plotted in Fig. 5.E3. Engine 15 is se-

lected for further investigation (even though Engine 20 saves 19 lbf more fuel)

because it saves significant fuel while keeping the engine specific thrust above

110 lbf/(lbm/s). Compressor pressure ratios above 28 are not shown because they

result in temperatures leaving the compressor greater than 1660°R at the maximum

Mach flight condition of 1.8M/40 kft.

When the reference point altitude of Engine 15 is changed to 35 kft (Engine

21), less fuel is saved. And when it is changed to 37 kft (Engine 22), more fuel

is saved. However these savings are exaggerated when compared with Engine

15 because the difference in power takeoff

(Pro)

accounts for about 8 lbf of

fuel (assuming a thermal efficiency of 45%, 300kW of

Pro

for the 1.5 hr AAF

mission consumes 185 lbf of fuel). Thus the savings caused by altitude changes

are negligible. Likewise the changes in fuel saved for the changes in design Mach

number (Engines 23 and 24) are caused mainly by the changes in power takeoff

(Pro).

Note that the specific thrust

(F/mo)

does not appear to change with

compressor pressure ratio (7rc) for a given fan pressure ratio (~rf). This is be-

cause the exit total pressure is determined by the fan pressure ratio (7~f) and the

exit total temperature (T~7) is fixed. The increases in compressor pressure (~rc) per-

mit larger engine bypass ratios (o0 with corresponding lower fuel consumption.

184 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

The Engine 15 design parameters are as follows:

M0 = 1.451 7/'f = 3.5

Tt4 =

3200°R Crow = 0.0152

h = 36 kft c¢ = 0.7563 Tt7 = 3600°R

Zrc = 28 M6 = 0.4 rh0 = 200 lbm/s

The results of the reference point calculations for the Engine 15 engine were

given earlier in sample printout A. Sample printout B and sample printout C give

the performance of this engine at one full throttle and partial throttle operating

condition, respectively.

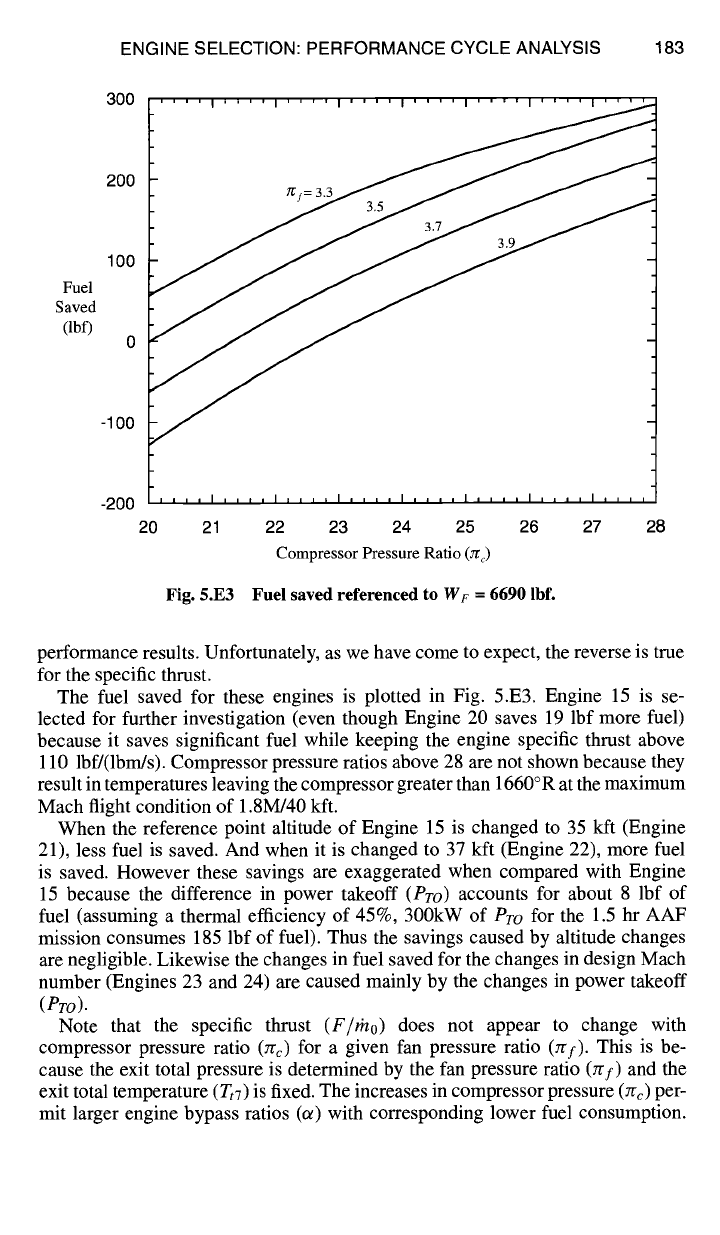

5.4.6 AAF Engine: Operational Envelope and Mission Performance

Having selected a promising engine for the AAF, its capability to operate over the

aircraft's flight regime must be confirmed and its performance for all mission legs

determined. The operational envelope is confirmed, as with the baseline engine, by

flying the engine at military power over the expected Mach number/altitude flight

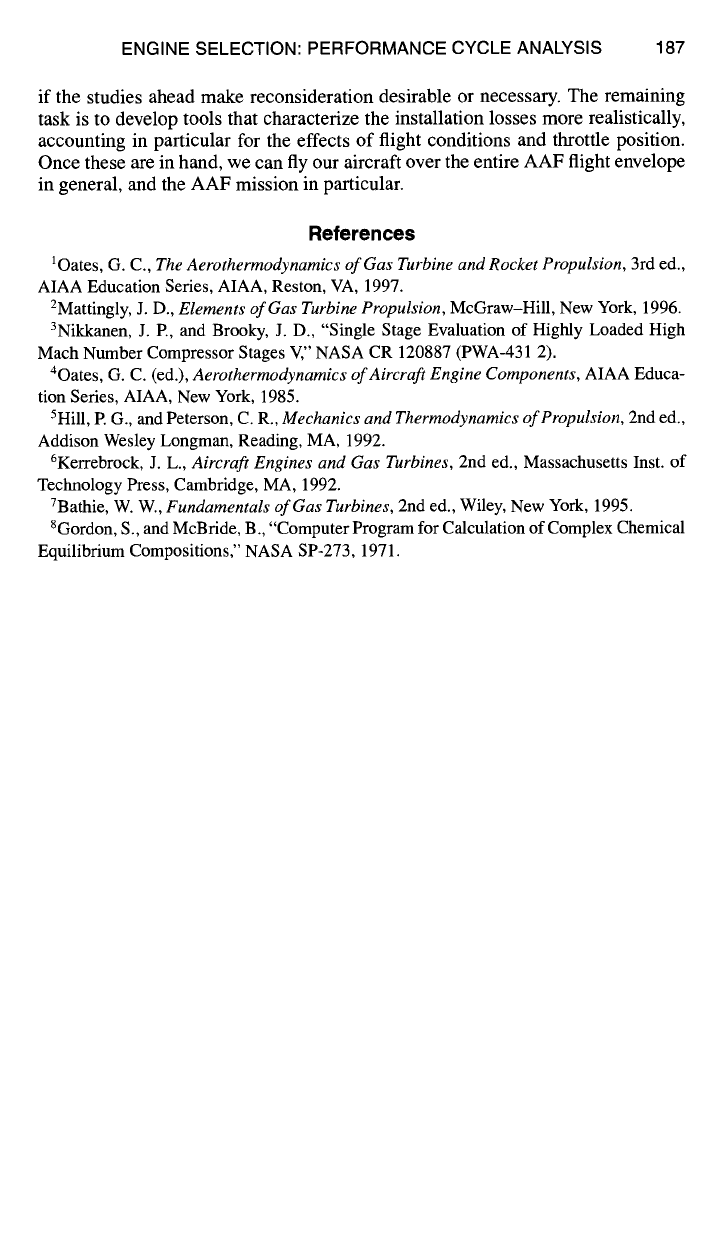

envelope of the AAE The engine operational envelope thus obtained is shown

in Fig. 5.E4. The flight regime of the AAF is well within the engine operational

envelope.

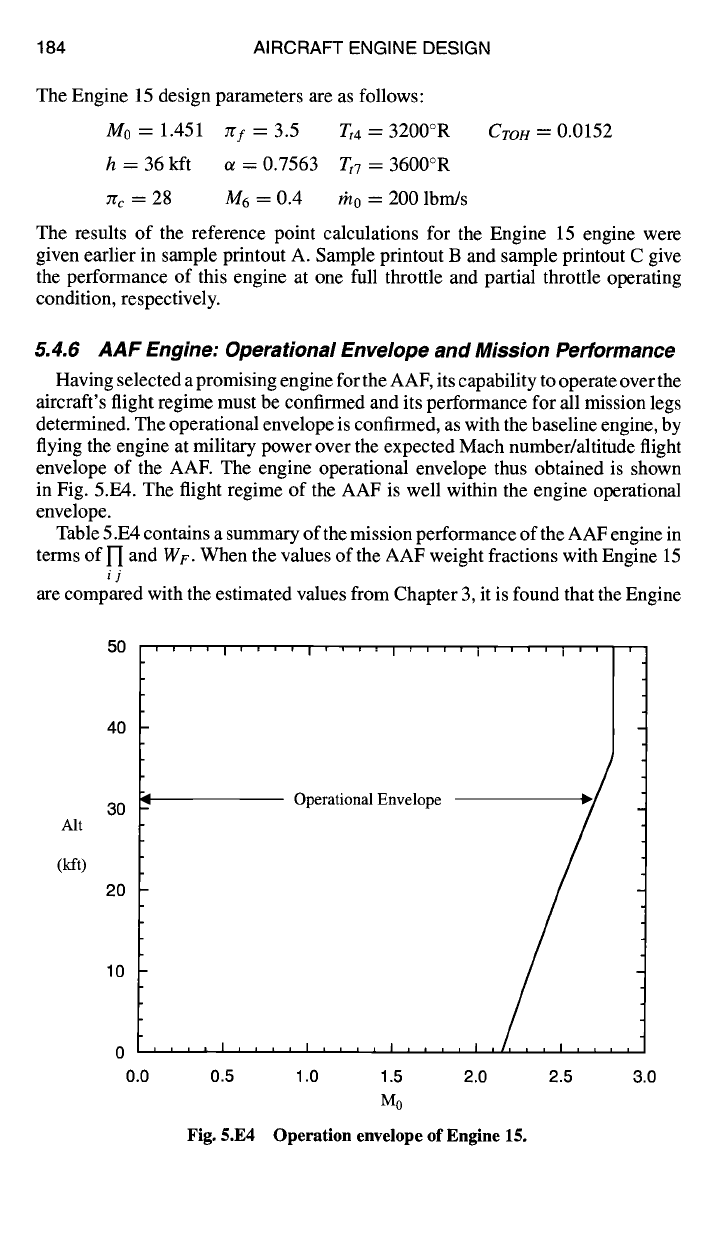

Table 5.E4 contains a summary of the mission performance of the AAF engine in

terms of ['I and WF. When the values of the AAF weight fractions with Engine 15

ij

are compared with the estimated values from Chapter 3, it is found that the Engine

Alt

(kft)

50 ' ' ' ' I ' '

40

30

20

10

0 , , , , I

0.0 0.5

' ' I ' ' ' ' I ' ' ' ' I ' ' ' ' I 'i~ ' '

-- Operational Envelope

, , I , , , i ]

I I I I ] I I

1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0

Mo

Fig. 5.E4 Operation envelope of Engine 15.

ENGINE SELECTION: PERFORMANCE CYCLE ANALYSIS

Table 5.E4 AAF

mission--Englne 15

185

Mission phases and segments

Table 3.E3 Engine 15

l-I w~, lbf H

WF,

lbf % change

if if

1-2: A Warm-up 0.9895 252 0.9916 202 -19.4

1-2: B Takeoff acceleration 0.9958 100 0.9952 113 13.0

1-2: C--Takeoff rotation 0.9984 39 0.9984 38 -2.6

2-3: D--Horizontal acceleration 0.9935 155 0.9942 138 - 11.0

2-3: E~limb/acceleration 0.9806 453 0.9804 461 1.8

3-4: Subsonic cruise climb 0.9736 607 0.9796 471 -22.4

5-6: Combat air patrol 0.9675 729 0.9719 634 -13.0

6-7: F---Acceleration 0.9837 354 0.9809 420 18.6

6-7: G--Supersonic penetration 0.9382 1317 0.9460 1161 -11.8

7-8: I--1.6M/5g turn 0.9753 478 0.9748 497 4.0

7-8: J--0.9M/5g turns a 0.9774 427 0.9716 546 27.9

7-8: K--Acceleration 0.9828 317 0.9803 369 16.4

8-9: Escape dash 0.9795 358 0.9819 319 -10.9

9-10: Zoom climb 0.9970 51 0.9975 46 -9.8

10-11: Subsonic cruise climb 0.9698 516 0.9734 457 -11.4

12-13: Loiter 0.9677 535 0.9674 547 2.2

Total 6688 6417 -4.2

aIncrease required from TSL / WTO

=

1.25 to meet thrust required for 0.9 M/30 kft, 5g turn at maneuver

weight.

15 uses significantly less fuel in the Warm-up 1-2 A, Horizontal Acceleration

2-3, Subsonic Cruise Climb 3-4, and Supercruise 6-7 phases. For all other mission

phases, the Engine 15 consumes about the same or more fuel, with the net result

that Engine 15 consumes 4% less fuel for the complete mission giving a cushion

of 271 lbf vs the total fuel consumption of 6690 lbf of Chapter 3.

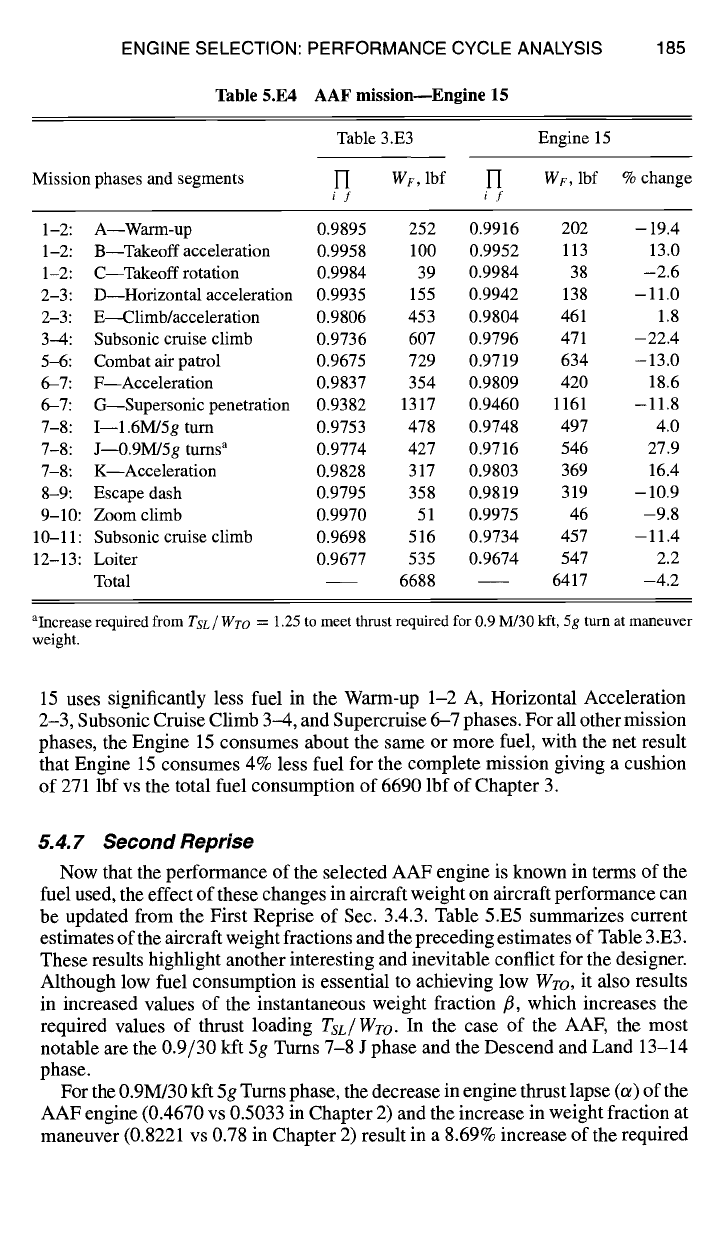

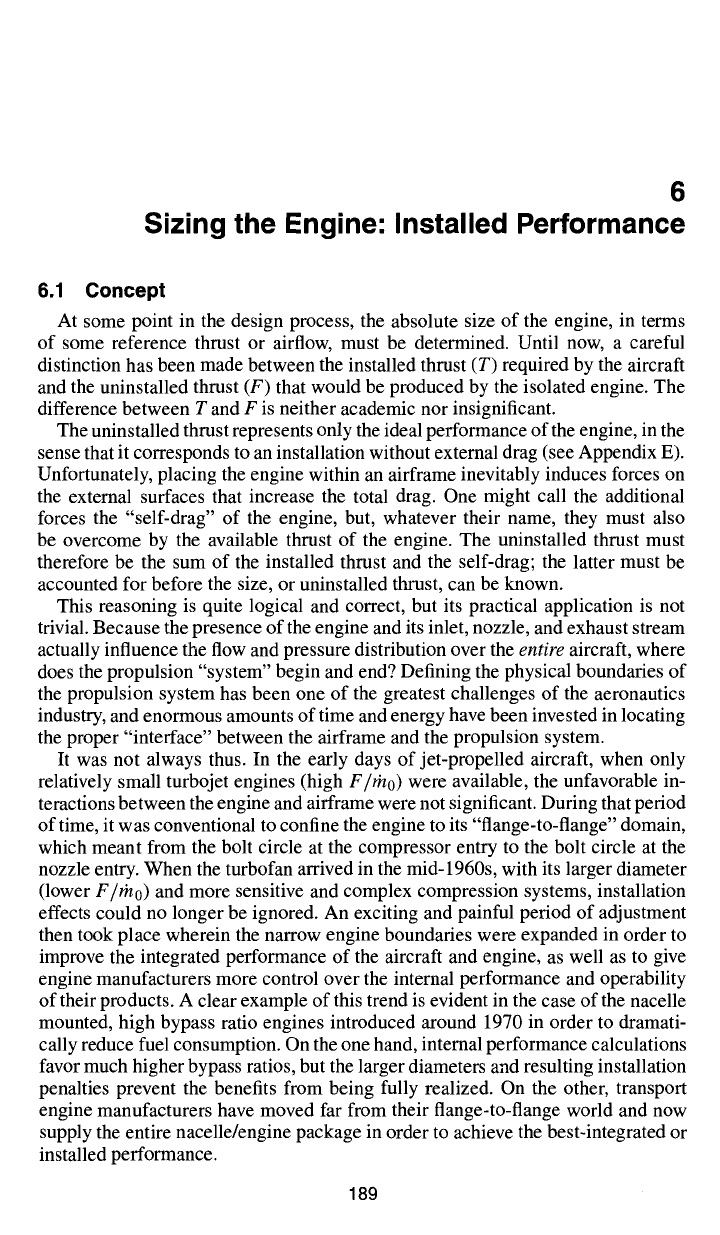

5.4.7 Second Reprise

Now that the performance of the selected AAF engine is known in terms of the

fuel used, the effect of these changes in aircraft weight on aircraft performance can

be updated from the First Reprise of Sec. 3.4.3. Table 5.E5 summarizes current

estimates of the aircraft weight fractions and the preceding estimates of Table 3.E3.

These results highlight another interesting and inevitable conflict for the designer.

Although low fuel consumption is essential to achieving low

Wro,

it also results

in increased values of the instantaneous weight fraction/3, which increases the

required values of thrust loading

TSL/Wro.

In the case of the AAF, the most

notable are the 0.9/30 kft 5g Turns 7-8 J phase and the Descend and Land 13-14

phase.

For the 0.9M/30 kft 5g Turns phase, the decrease in engine thrust lapse (or) of the

AAF engine (0.4670 vs 0.5033 in Chapter 2) and the increase in weight fraction at

maneuver (0.8221 vs 0.78 in Chapter 2) result in a 8.69% increase of the required

186

AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

Table 5.E5 Summary of resultsmmission analysis--24,000 lbf

Wro

Mission phases and segments

Table 3.E3 Table 5.E4

/3 at end of leg 1-[ /3 at end of leg l~

if if

1-2 A: Warm-up 0.9895 0.9895 0.9916 0.9916

1-2 B: Takeoff acceleration 0.9853 0.9958 0.9868 0.9952

1-2 C: Takeoff rotation 0.9837 0.9984 0.9853 0.9984

2-3 D: Acceleration 0.9773 0.9935 0.9795 0.9942

2-3 E: Climb/acceleration 0.9584 0.9806 0.9603 0.9804

3-4: Subsonic cruise climb 0.9331 0.9736 0.9407 0.9796

4-5: Descend 0.9331 1.0000 0.9407 1.0000

5-6: Combat air patrol 0.9027 0.9675 0.9143 0.9719

6--7 F: Acceleration 0.8880 0.9837 0.8968 0.9809

6-7 G: Supersonic penetration 0.8331 0.9382 0.8485 0.9461

7-8 H: Fire ARAAMs 0.8060 0.8213

7-8 I: 1.6M/5g turn 0.7860 0.9753 0.8006 0.9748

7-8 J: 0.9M/5g turns 0.7682 0.9774 0.7778 0.9716

7-8 K: Acceleration 0.7550 0.9828 0.7625 0.9803

7-8 L: Fire AIM-9Ls and ½ ammo 0.7276 0.7351

8-9: Escape dash 0.7127 0.9795 0.7218 0.9819

9-10: Minimum time climb 0.7106 0.9970 0.7199 0.9974

10-11: Subsonic cruise climb 0.6891 0.9698 0.7009 0.9735

11-12: Descend 0.6891 1.0000 0.7009 1.0000

12-13: Loiter 0.6668 0.9677 0.6781 0.9674

13-14: Descend andland 0.6668 1.0000 0.6781 1.0000

End Remove permanent payload 0.6106 0.6219

thrust loading from 1.25 to 1.36. Because this is based on a installation loss of 5%

for this full throttle flight condition where the engine is limited by the compressor

pressure ratio, this estimate is most likely conservative, and the thrust loading will

not be changed until a better estimate of the installation loss is obtained in the next

chapter.

Constraint analysis shows that the increase in landing weight fraction requires

either a decrease in the wing loading from 64 to 62.7 lbf/ft 2 or an increase in

the maximum lift coefficient for landing from 2.0 to 2.05. The increase in maxi-

mum lift coefficient is preferred to keep the wing area down and its resultant fuel

consumption at cruise. Consequently, Engine 15 meets all the known constraints

and promises satisfactory fuel consumption for the AAF mission, and provides a

satisfactory starting point for the remaining studies.

We would do well to pause at this point to take stock of our situation. We have

come far in short order because of the powerful conceptual and computational tools

at our disposal. Several promising reference point engines have been discovered

that can apparently make possible an aircraft that can meet all of the requirements

of the AAF RFP. One of those engines, designated Engine 15, has been selected

for further investigation, although we are free to return to this step to choose others

ENGINE SELECTION: PERFORMANCE CYCLE ANALYSIS 187

if the studies ahead make reconsideration desirable or necessary. The remaining

task is to develop tools that characterize the installation losses more realistically,

accounting in particular for the effects of flight conditions and throttle position.

Once these are in hand, we can fly our aircraft over the entire AAF flight envelope

in general, and the AAF mission in particular.

References

1Oates, G. C.,

The Aerothermodynamics of Gas Turbine and Rocket Propulsion,

3rd ed.,

AIAA Education Series, AIAA, Reston, VA, 1997.

2Mattingly, J. D.,

Elements of Gas Turbine Propulsion,

McGraw-Hill, New York, 1996.

3Nikkanen, J. P., and Brooky, J. D., "Single Stage Evaluation of Highly Loaded High

Mach Number Compressor Stages V," NASA CR 120887 (PWA-431 2).

4Oates, G. C. (ed.),

Aerothermodynamics of Aircraft Engine Components,

AIAA Educa-

tion Series, AIAA, New York, 1985.

5Hill, P. G., and Peterson, C. R.,

Mechanics and Thermodynamics of Propulsion,

2nd ed.,

Addison Wesley Longman, Reading, MA, 1992.

6Kerrebrock, J. L.,

Aircraft Engines and Gas Turbines,

2nd ed., Massachusetts Inst. of

Technology Press, Cambridge, MA, 1992.

7Bathie, W. W.,

Fundamentals of Gas Turbines,

2nd ed., Wiley, New York, 1995.

8 Gordon, S., and McBride, B., "Computer Program for Calculation of Complex Chemical

Equilibrium Compositions," NASA SP-273, 1971.

6

Sizing the Engine: Installed Performance

6.1 Concept

At some point in the design process, the absolute size of the engine, in terms

of some reference thrust or airflow, must be determined. Until now, a careful

distinction has been made between the installed thrust (T) required by the aircraft

and the uninstalled thrust (F) that would be produced by the isolated engine. The

difference between T and F is neither academic nor insignificant.

The uninstalled thrust represents only the ideal performance of the engine, in the

sense that it corresponds to an installation without external drag (see Appendix E).

Unfortunately, placing the engine within an airframe inevitably induces forces on

the external surfaces that increase the total drag. One might call the additional

forces the "self-drag" of the engine, but, whatever their name, they must also

be overcome by the available thrust of the engine. The uninstalled thrust must

therefore be the sum of the installed thrust and the self-drag; the latter must be

accounted for before the size, or uninstalled thrust, can be known.

This reasoning is quite logical and correct, but its practical application is not

trivial. Because the presence of the engine and its inlet, nozzle, and exhaust stream

actually influence the flow and pressure distribution over the entire aircraft, where

does the propulsion "system" begin and end? Defining the physical boundaries of

the propulsion system has been one of the greatest challenges of the aeronautics

industry, and enormous amounts of time and energy have been invested in locating

the proper "interface" between the airframe and the propulsion system.

It was not always thus. In the early days of jet-propelled aircraft, when only

relatively small turbojet engines (high F/mo) were available, the unfavorable in-

teractions between the engine and airframe were not significant. During that period

of time, it was conventional to confine the engine to its "flange-to-flange" domain,

which meant from the bolt circle at the compressor entry to the bolt circle at the

nozzle entry. When the turbofan arrived in the mid-1960s, with its larger diameter

(lower F/tho) and more sensitive and complex compression systems, installation

effects could no longer be ignored. An exciting and painful period of adjustment

then took place wherein the narrow engine boundaries were expanded in order to

improve the integrated performance of the aircraft and engine, as well as to give

engine manufacturers more control over the internal performance and operability

of their products. A clear example of this trend is evident in the case of the nacelle

mounted, high bypass ratio engines introduced around 1970 in order to dramati-

cally reduce fuel consumption. On the one hand, internal performance calculations

favor much higher bypass ratios, but the larger diameters and resulting installation

penalties prevent the benefits from being fully realized. On the other, transport

engine manufacturers have moved far from their flange-to-flange world and now

supply the entire nacelle/engine package in order to achieve the best-integrated or

installed performance.

189

190 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

For such high performance aircraft as the Air-to-Air Fighter (AAF) of this

textbook, the engine is likely to be "buried" within the fuselage, and the division

of territorial jurisdiction becomes difficult. The engine designer would like to have

control over those external surfaces that directly interact with the engine, but cannot

possibly be responsible for the entire envelope that surrounds the engine. In the

end, the engine designer will be allowed to influence those parts that are believed

to generate the bulk of the installation penalties and are affected by the inlet

and exhaust flows. This will generally include the inlet and the nozzle, the exact

boundaries being decided by negotiation in each case. As you will see, the external

drag on the inlet and nozzle is strongly affected by the throttle setting, and it is

therefore referred to as "throttle dependent drag."

The foregoing should persuade you that engine integration has itself become a

major technology in modern aircraft design and development. Aircraft and engine

companies alike have invested heavily in this area and now have expert orga-

nizations available to deal with its problems; the government and industry have

acted collectively to produce clarifying standards. ~ Today it is known that engine

integration can have beneficial and satisfying results when considered from the

outset and done properly. When done poorly (or not at all), development crises

are invited that, in the past, have led to dramatic examples of reduced aircraft per-

formance and engine operability, increased program time and cost, and/or bitter

recriminations.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide some preliminary tools for estimating

the installation penalties that must be compensated for by added uninstalled thrust.

Only inlet and nozzle external losses will be considered, and they will be expressed

in their most convenient form, namely as a fraction of the uninstalled thrust, so that

T = F

- ~inletF - q)nozzle F

or

where

and

T

F = > T (6.1)

1 - qSi.le, - (anozzte

(Pinlet = Dintet/ F

(6.2a)

#Pnozzle = Dnozzle / F

(6.2b)

Please note that

~)inlet

and

4~nozzle

will vary with flight condition and throttle setting

for any given engine.

In addition to entering a territory rich in history and jurisprudence, this is the first

encounter in this textbook with individual engine components: inlets and nozzles.

In later chapters, the focus will be on their internal behavior in order to ensure that

they will deliver the performance assumed in the cycle calculations, but now only

their external behavior will be considered. Despite their outward appearance of

simplicity, inlets and nozzles are actually very complex devices because they must

meet many simultaneous requirements and they can have a very detrimental effect

on system performance if they do not function properly. Much good technical

work on engine/aircraft integration has been accomplished and reported over

the past 30 years, so that many references are now available. The basics can be

SIZING THE ENGINE: INSTALLED PERFORMANCE 191

found in Refs. 2 and 3, and an excellent survey is located in Chapter 4 of Ref. 4.

The contents of Ref. 4 also have been updated and have been published in three

textbooks as part of the AIAA Education Series; see Refs. 2, 5, and 6. From such

writings it is possible to construct a partial list of the requirements to be met by

inlets and nozzles that emphasizes the many roles they play, as follows:

Both inlets and nozzles:

1) Minimize installation drag on their own and adjacent aircraft surfaces (over

wide ranges of angles of attack and throttle settings).

2) Maximize internal total pressure recovery (Jra, Zrn).

3) Provide controllable flow matching for all operating conditions. (Remember,

the engine knows how much flow it wants.)

4) Minimize weight and cost while meeting life and reliability goals.

5) Suppress acoustic and radar signatures.

Inlets:

6) Control inlet spatial and temporal distortion.

7) Provide good starting and stability characteristics.

Nozzles:

8) Suppress infrared (IR) signatures.

9) Provide thrust reversing and vectoring.

Merely skimming Ref. 5 will reveal that many types of inlets and nozzles have

been developed to meet these requirements, depending upon the specific operating

conditions. It will also become clear that the analysis and testing of these devices

have become very sophisticated. Nevertheless, it is not the purpose of this textbook

to provide comprehensive design methods for every conceivable inlet and nozzle

configuration. Instead, some typical preliminary design estimation tools for

~inlet

and q~nozJe will be developed. If more accuracy is required, the open literature is

recommended.

What really matters here is that some account must be made at this point in the

design cycle for installation penalties. The sooner the problems are identified, the

sooner the engine and aircraft designers can start working to solve them.

Once an agreement is reached on the means for computing

q)inlet

and Cbnozzle

as a function of flight conditions (altitude, Mach number, and angle of attack)

and throttle setting

(Tt4

and Tt7), the engine performance models of Chapter 5

contained within the AEDsys program may be used to size the engine. Starting

from the design point engine and mass flow selected by the methods of Chapter 5,

the engine is "tested" at each critical flight condition at either military power or

maximum power in accordance with the Request for Proposal (RFP) requirement

and then the engine is "flown" through the mission. Next, either the engine mass

flow (size) is adjusted until the required and available thrust are equal at the flight

condition requiring the largest engine by the method of Fig. 6.E2 or the required

size may be found in the following manner. From Eqs. (2.2a) and (6.1) it follows

for each flight condition that

F T

rh 0 _ m

F/r'no

(F/m0)(1 -

4~in~e, - q~,ozz~e)

W[(D + R)/W + Ps/V]

(F//~/0)(1 --

q~inlet -- ~9nozzle)

(6.3)

192 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

To find which of the flight conditions is most "demanding" (that is, requires the

largest engine), each rn0 is merely multiplied by the relevant,

(lJlOreq/rnOavail)

eval-

uated at sea level static as obtained from the performance computations. The

procedure for determining these quantities will be described in detail in Sec. 6.4.3.

You will be pleased to discover that this sizing process has been automated in

AEDsys via the Thrust Scale Factor. The largest resulting product corresponds to

what would be the largest design point engine and, therefore, the required size.

This engine will, naturally, be too large for all except the most demanding flight

condition, and actual performance at the others must be obtained later by throttling

down

Tt4

and/or

Tt7

until

F = W + -~- (1

--

(Pinlet -- q~nozzle)

(6.4)

for an engine of the chosen size. Not until this is done will the true behavior of the

engine, and especially its fuel consumption, be known.

6.2 Design Tools

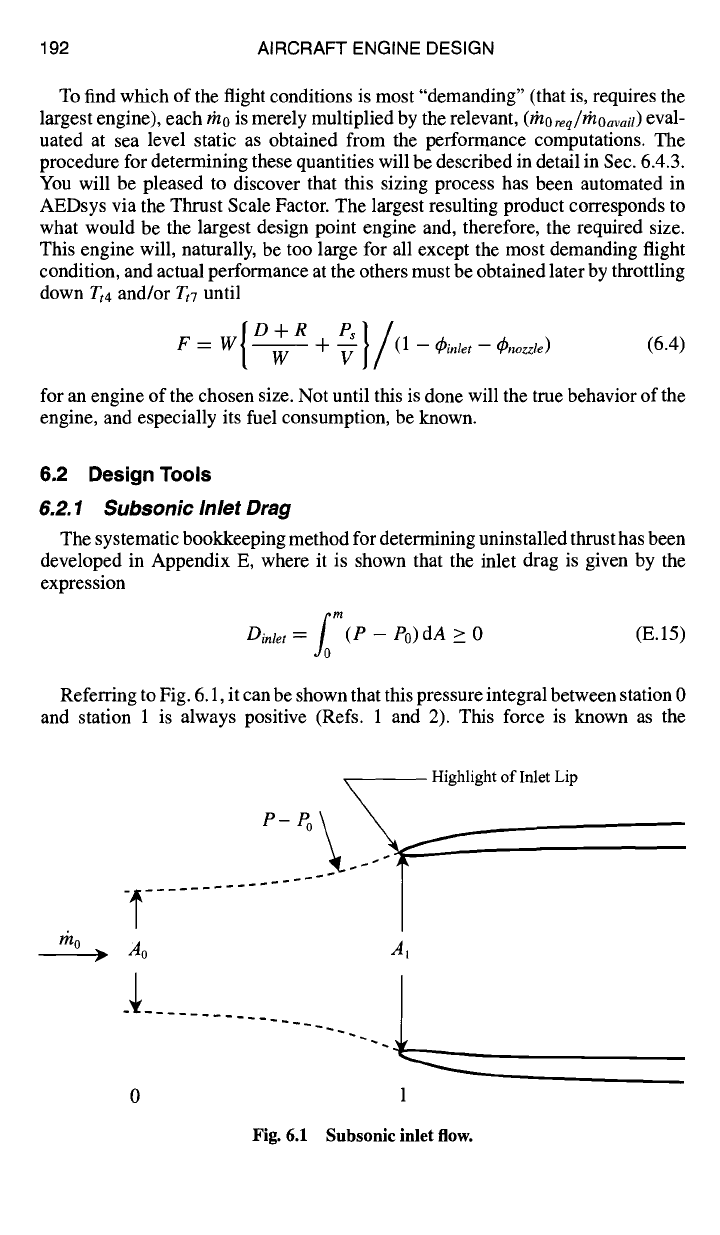

6.2.1 Subsonic Inlet Drag

The systematic bookkeeping method for determining uninstalled thrust has been

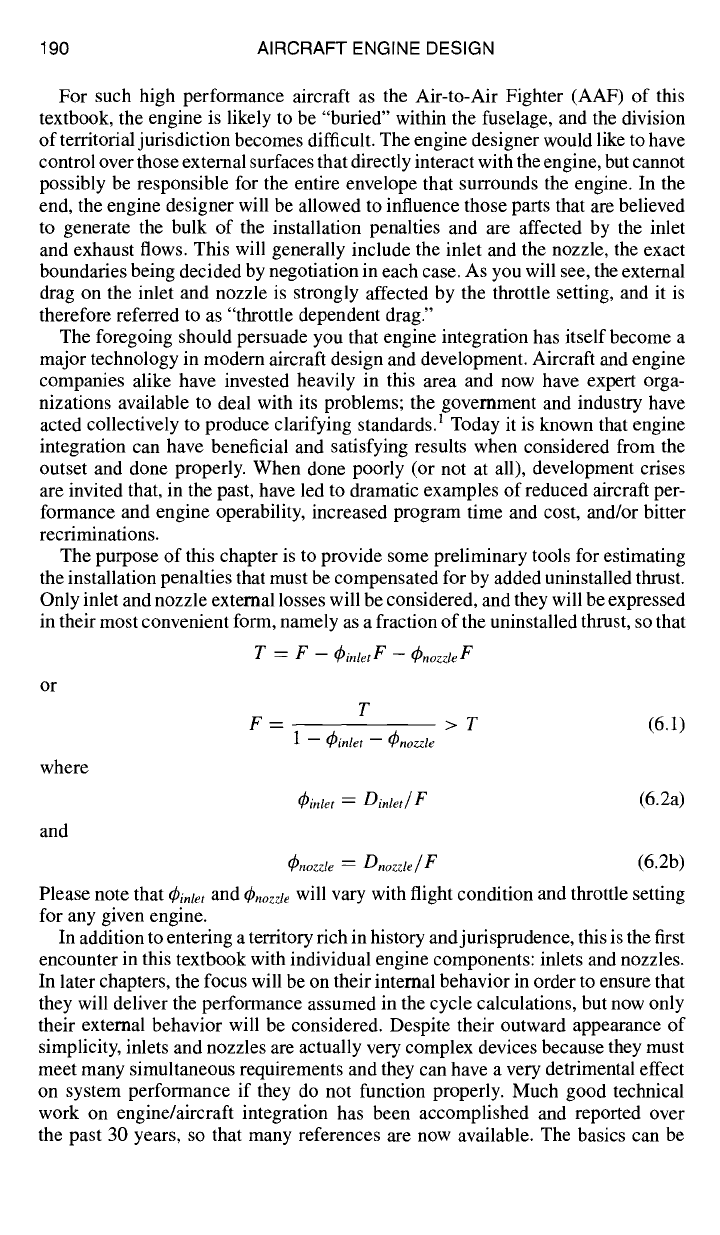

developed in Appendix E, where it is shown that the inlet drag is given by the

expression

fo m

Dinlet :-

(P -

P0)dA > 0 (E.15)

Referring to Fig. 6.1, it can be shown that this pressure integral between station 0

and station 1 is always positive (Refs. 1 and 2). This force is known as the

rho

Highlight of Inlet Lip

Ao Ai

U

0 1

Fig. 6.1 Subsonic inlet flow.