Mattingly J.D., Heiser W.H., Pratt D.T. Aircraft Engine Design

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

172 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

40 kft

7

Compressor

Pressure

Ratio (z~)

6

3 J L ~ L I ~ ~ i ~ I ~ , , , I ~ ~ , ,

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5

M0

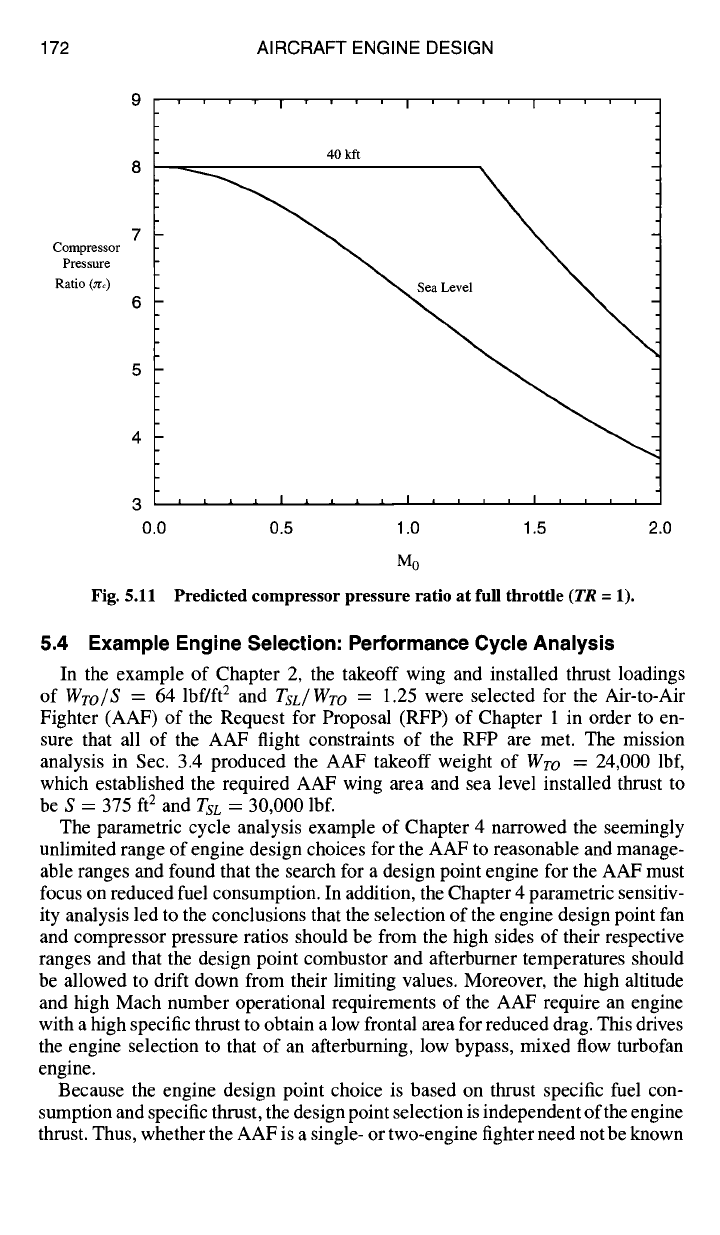

Fig. 5.H Predicted compressor pressure ratio at full throttle

(TR

=

]).

2.0

5.4 Example Engine Selection: Performance Cycle Analysis

In the example of Chapter 2, the takeoff wing and installed thrust loadings

of

WTo/S

= 64 lbf/ft 2 and

TsL/Wro

= 1.25 were selected for the Air-to-Air

Fighter (AAF) of the Request for Proposal (RFP) of Chapter 1 in order to en-

sure that all of the AAF flight constraints of the RFP are met. The mission

analysis in Sec. 3.4 produced the AAF takeoff weight of

WTO

= 24,000 lbf,

which established the required AAF wing area and sea level installed thrust to

be S = 375 ft 2 and

TsL

= 30,000 lbf.

The parametric cycle analysis example of Chapter 4 narrowed the seemingly

unlimited range of engine design choices for the AAF to reasonable and manage-

able ranges and found that the search for a design point engine for the AAF must

focus on reduced fuel consumption. In addition, the Chapter 4 parametric sensitiv-

ity analysis led to the conclusions that the selection of the engine design point fan

and compressor pressure ratios should be from the high sides of their respective

ranges and that the design point combustor and afterburner temperatures should

be allowed to drift down from their limiting values. Moreover, the high altitude

and high Mach number operational requirements of the AAF require an engine

with a high specific thrust to obtain a low frontal area for reduced drag. This drives

the engine selection to that of an afterburning, low bypass, mixed flow turbofan

engine.

Because the engine design point choice is based on thrust specific fuel con-

sumption and specific thrust, the design point selection is independent of the engine

thrust. Thus, whether the AAF is a single- or two-engine fighter need not be known

ENGINE SELECTION: PERFORMANCE CYCLE ANALYSIS 173

until the engine is sized. When the engine is sized, however, in Chapter 6, the

number of engines must be specified by the airframe and propulsion design teams.

With the detailed results of the preceding examples and the parametric

(on-design) and performance (off-design tools) embedded in the textbook's com-

puter programs ONX and AEDsys, the systematic search begun in Chapter 4 for

an optimum combination of engine design choices that satisfy the AAF mission

requirements will now be extended. In the search here, the influence of each of

the design parameters on the engine performance at the off-design critical flight

conditions of the mission is determined. The goal is to find the best combination

of design choices for the AAF engine. The search is well on its way as a result of

the extensive work accomplished in Sec. 4.4.

5.4.1 Critical Flight Conditions

The first engine to be selected in the search for the optimum AAF design point

engine will serve as the baseline engine. The performance of this engine over the

critical legs of the mission forms a basis for comparison of other engine candidates.

It is necessary at the outset, therefore, to establish which mission legs are to be

judged as critical for the search. Any leg that 1) has a high fuel consumption

(low Iq) as determined from Table 3.E3 and Sec. 3.4.4; 2) represents a boundary

of the solution space in the revised constraint diagram of Fig 3.E5; or 3) is an

extreme operating condition should be considered critical. Based on these criteria,

the flight conditions listed in Table 5.El are considered critical for this study. The

power setting or, if the leg is at constant speed, the required uninstalled thrust

[Freq

= D/0.95, allowing in Eq. (6.1) for 5% installation losses] is given in the

table for each mission leg listed. The required thrust can be used in the AEDsys

performance analysis to find the requisite throttle setting (i.e.,

Tt4

and TtT) for type

B, Ps

= 0 legs. The weight fraction and the estimated installed thrust specific fuel

consumption

(TSFC)

obtained in Sec. 3.3 are also listed for those legs considered

fuel critical. The last four legs given in the table represent the takeoff constraint

boundary limit, Combat Turn 2 constraint (0.9/30 kft, 5g), and the maximum Mach

number extreme operating condition.

5. 4.2 Mission Fuel Consumption

Mission fuel usage plays a dominant role in the selection of the AAF engine

design. There are two methods for calculating the fuel used: 1) the mission analysis

portion of the AEDsys computer program, or 2) an estimate based on the algebraic

analysis of Sec. 3.4.2.

Computer calculated mission analysis.

Based on an input takeoff weight,

the mission analysis portion of the AEDsys computer program flies the aircraft

and reference point engine through the mission and determines the fuel used for

each leg and the overall fuel used. This powerful tool includes the engine per-

formance engine model described in this chapter. All you need to do to begin is

design an engine using the ONX computer program's "single point" calculation

capability and save the resulting reference engine as a reference data file (*.REF).

The reference data file is then input into the AEDsys program by selecting "Cycle

Deck" from the Engine pull-down menu (or opening the "Engine Data" window),

174 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

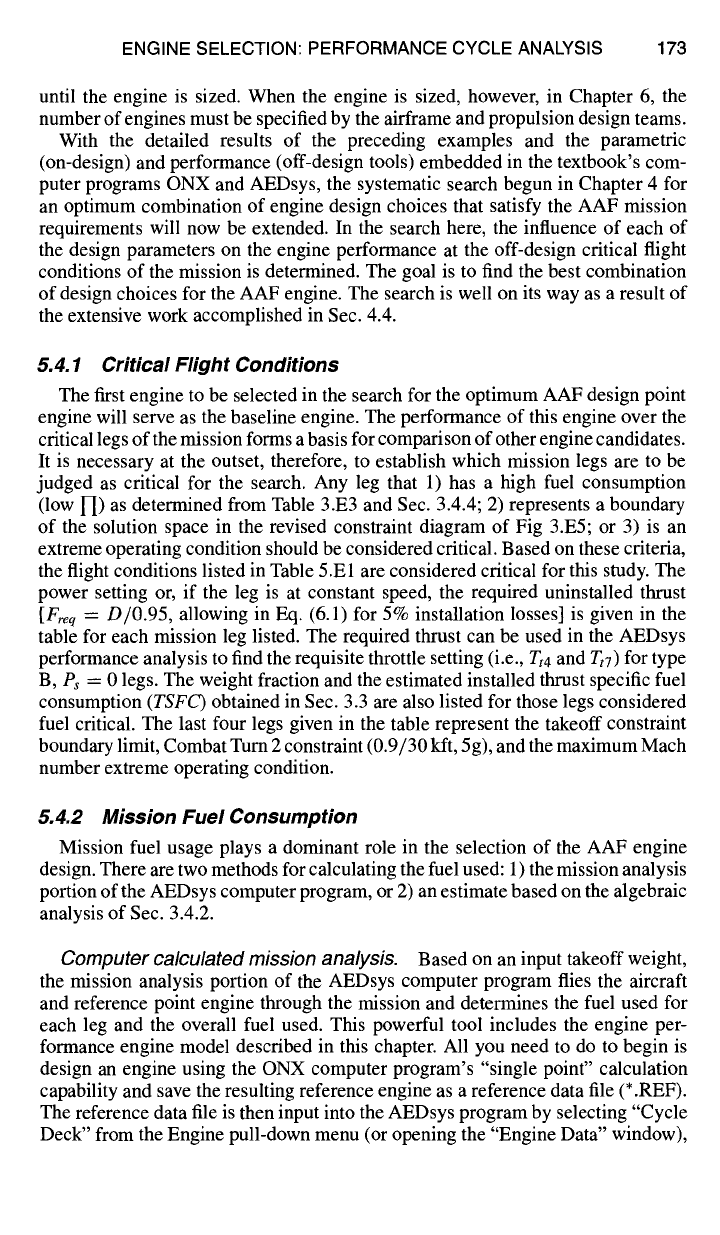

Table 5.El AAF critical mission legs

Mission phases and segments

Table 3.E3

M0 Alt, kft

Freq,

lbf

1-'[ TSFC, 1/h

1-2: A--Warm-up 0.00 2 a Mil 0.9895 0.9352

2-3: E--Climb/acceleration 0.875 23 Mil 0.9806 1.067

3-4: Subsonic cruise climb 0.9 42 2,600 0.9736 1.015

5-6: Combat air patrol 0.697 30 2,366 0.9675 0.9883

6-7: F--Acceleration 1.09 30 Max 0.9837 1.688

6-7: G--Supersonic 1.5 30 11,305 0.9382 1.203

penetration

7-8: I--1.6M/5g turn 1.6 30 19,170 0.9753 1.509

7-8: J----O.gM/5g turns 0.9 30 14,840 0.9774 1.544

7-8: K Acceleration 1.2 30 Max 0.9828 1.713

8-9: Escape dash 1.5 30 11,190 0.9795 1.203

10-11: Subsonic cruise climb 0.9 48 1,926 0.9698 1.015

12-13: Loiter 0.394 10 1,747 0.9677 0.9825

1-2: B--Takeoff acceleration 0.1 2 a Max

1-2: C--Takeoff rotation 0.182 2 a Max

0.gM/5g turns at 0.9 30 16,030

Maneuver weight

Maximum Mach 1.8 40 10,210

aAtl00°F.

selecting the "input reference data file" function, and entering the file name. Then

the maximum compressor pressure ratio (and other operational limits) must be

entered into the engine controls input data. The constant installation loss model

is selected until better installation loss models become available (see Chapter 6)

and the appropriate estimate of the loss entered into the input field. Then the

"Engine Data" window is closed and the "Mission" window opened. Each leg of

the mission is reviewed and the appropriate throttle limits set for Tt4. Refer to the

AEDsys Users Manual

on the accompanying CD-ROM for detailed instructions.

Algebraic mission analysis estimate.

The mission fuel fraction, from

Sec. 3.4.2, is

WF

1-- +-- 1-- +-- 1-- (5.El)

WTO Wro Wro

Because this expression is a function of the weight fractions l-i, l-i, and l-I, the

In jn kn

most important need is for a simple method for finding the weight fraction (I-[)

ij

of each critical mission leg for a 2given engine design. As a critical mission leg

is flown with different reference point engines, only the value of the

TSFC

term

of Table 5.El will change in the weight fraction equation for the leg. Therefore,

from either Eq. (3.14) when Ps > 0 or Eq. (3.16) when

Ps

= 0, for any given leg

ENGINE SELECTION: PERFORMANCE CYCLE ANALYSIS 175

flown with a different engine,

H = exp{-TSFC x constant} (5.E2)

ij

and for the special case of warm-up with a different engine, Eq. (3.42) yields,

assuming the same thrust lapse for all engines,

U = 1 - TSFC x constant (5.E3)

ij

Therefore, in order to find 1-[ for a candidate engine in the search for an optimum

ij

engine, it is necessary only to adjust the Table 5.El value of l--[ to reflect the new

ij

TSFC as found from the engine cycle analysis. It is important to recall at this

point that the TSFC values of Table 5.El are based on the highly generalized

models found in Sec. 3.3.2. You should therefore expect to find differences, some

significant, between the universal models and the AEDsys cycle computations.

The goal of the search remains, in fact, to find reference point engines that, on

balance, are clearly superior.

Because the AEDsys engine performance analysis gives S, the uninstalled thrust

specific fuel consumption, the mission analysis TSFC is estimated as S/0.95, which

allows 5% for installation losses. Therefore, the adjusted mission leg fraction

{(I-DN} can be found from Table 5.El data and the AEDsys engine performance

ij

analysis data by the equations

N \i j/

in general, and

1

N

for warm-up. These equations follow directly from Eqs. (5.E2) and (5.E3).

(5.E4)

(5.E5)

5.

4.3 Getting Started

The search for the AAF engine begins with a baseline reference point engine and

its off-design performance over the critical mission legs given in Table 5.El. But

how are the design choices (M0, h, zrc, ~rf, or, Tt4, TtT, and Mr) for the first engine

to be chosen? A great wealth of guidance is available to help with this selection.

In the first place, the reference point study of Sec. 4.4 reduced the design choices

to the following manageable ranges:

1.2<M0< 1.6

30<h<45kft

15 </rc < 25

0.3 <ot<0.4

176 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

3<7rf <5

Tt4 ~ 3200°R

T,7 < 3600°R

0.35 < M6 < 0.45

In addition, the conclusions of the sensitivity study of Sec. 4.4.5 indicated that Tgf

and 7rc should be selected from the high ends of their respective ranges, while,

Tt4

and/or To should be allowed to drift down from their limiting values in order to

reduce fuel consumption. Moreover, as shown in Sec. 4.3.4, the selections of 7rc

and 2"/'f are interdependent. Because we will select cycles for which

try ~ ZrcL (5.E6)

then, from Eq. (4.34)

1

7Ccn ~ -- (5.E7)

7rtHTgtL

Finally, because zra4 and zrtL must be less than about 0.5 in order to ensure that the

turbine entrance nozzles are choked, we conclude that

rrd4 > 4 (5.E8)

Simultaneously, note that the requirement that zrtH and

7"gtL

be less than 0.5

requires

"CtH

and rtL to be less than about 0.87 [see Eqs. (4.9d) and (4.9e)]. This

impacts on the selection of try and a because Jrf, or, ra4, and

rtL are

related through

the low pressure spool power balance. As an approximation for the purposes here,

consider the low spool power balance for a turbofan with no bleed air, no turbine

cooling, and no power takeoff. Solving the low-pressure spool power balance

equation [Eq. (4.22a)] for 7rf yields

{ r]mL rgk VSml r:tHTgm2(1-- 72tL) lh4.5 } g'e/ /(Y'-l)

try = 1 + (1 + oe)rr the- (5.E9)

where, from Fig. 4.2

rh4.5

= (1 - fl - el

- e2)(1

+ f) + el + e2 ~ 1

rhc

Thus, Eq. (5.E9) provides a relationship between zrf and a for the given flight

conditions and design constants and for the approximate value of 0.87 for rtH and

r2tL.

Finally, as mentioned in Sec. 4.3.4, common sense would encourage keeping

the design choice of M6 in the range 0.354).45 because it is certain to migrate

away during off-design operation.

5.4.4 The Baseline Engine

The search is begun by selecting the reference point for a baseline engine, verify-

ing its operating envelope, performing a sensitivity analysis at its design point, and

determining its off-design performance. The sensitivity analysis provides guidance

ENGINE SELECTION: PERFORMANCE CYCLE ANALYSIS 177

in selecting subsequent engines to be studied, while the detailed off-design perfor-

mance of the baseline engine will illustrate the off-design analysis to be followed

for other candidate engines in the search. As noted in Sec. 4.2.8, the MSH (Mod-

ified Specific Heat) model is used in all of the ensuing AAF engine performance

calculations.

Selection: baseline engine.

Referring to the discussion of Sec. 4.4.4, the

reference point flight conditions for the baseline engine are selected to be M0 =

1.451 and 36,000 ft (00 = 1.07). The design values of Tr4 and

Tt7 are

selected to be

3200°R and 3600°R. These choices fix rr and rz at 1.421 and 10.07, respectively.

Now Eq. (5.E9) is used to relate the selection

ofYr/ande.

Using Fc = 1.4, vtt-/=

rtL =

0.87,

Vml ---- rm2 =

0.97,

OraL =

0.995,

ef

----

0.89, and

lh4.5/tn C

----

1.02

along with the design point values of rr and rz, Eq. (5.E9a) yields

{ 0.765} 3'2

~f=

1 + 1---~

Selecting a midrange bypass ratio of 0.4 for or, the reference point choice of

2Tf

from this equation is about 3.9. As suggested by the sensitivity study and in order

to make

Zrcn

> 4.0 [Eq. (5.E8)], a high range value of 20 is selected for 7rc, which

from Eq. (5.E7) gives a reference point value of 5.13 for erie. Finally, the Mach

number at station 6 is chosen to be 0.4 at the reference point.

Before the performance of any engine with power takeoff can be calculated,

an estimate of the nondimensional power takeoff

(CTo)

is required. We elect to

have the 300 kW of external power driven by the high-pressure spool to minimize

the impact on the mixer. Because the power takeoff,

Pro,

is a small fraction of

the overall power produced by the high-pressure turbine, a rough estimate of the

nondimensional power takeoff will suffice at this point. With

PTO _ I Pr° } F

CTO -- thoh~o [ Fho rh---oo

then values of F and

F/tho

need be determined only to obtain the desired estimate

because

Pro / ho

is known. From Table 4.1,

F/Fno

is estimated to be 110 lbf/(lbm/s).

Thus, with F =

TSL

= 30,000 lbf, we find the mass flow at the sea level static to

be

Fno = F/(F/r'no) ~

270 lbm/s

which is also the corrected mass flow rate at sea level static. Like the maximum

compressor pressure ratio, the corrected mass flow rate is limited to its sea level

static value for flight conditions where 00 <

TR

(see Appendix D). Because this

point corresponds to 00 .-~

TR,

the mass flow rate at the reference point can be

calculated from the corrected mass flow rate using Eq. (5.23) rewritten as

mo = ,h2 =

With rnc2 = 270 Ibm/s, 02 -- 00 =

TR

= 1.07, and 62 = 7rd3o = zrrrra6 = (3.421)

(0.9354)(0.2250) = 0.7200, then

rho = 270 × 0.720/l~/L~.07 ~ 200 lbm/s

178 AIRCRAFT ENGINE DESIGN

Hence, the nondimensional power takeoff, with

Pro

= 300 kW and h0 =

93.72 Btu/lbm

[Cp¢

= 0.24 Btu/(lbm-°R), To = 390.5°R, and h0 =

cpcTo],

is

estimated to be 0.01517 or in round figures, say, 0.0152, which makes

Pro =

300.6 kW ,~ 300 kW.

All engines to be examined in the search will use this design point value of

0.0152 for

Cro. In

addition, the mixer inlet design point Mach number (M6) will

be 0.4 for all engines to be studied.

Please bear in mind the fact that the size or scale of the engine, as represented

here by th0, can and will be easily changed within AEDsys to match the precise

requirements of the aircraft system over the entire mission. Moreover, the scale of

the engine has no effect on any specific performance properties, which includes

the vast majority of the engine cycle quantities of interest.

In summary, the reference point parameters for the baseline engine are as

follows:

M0 = 1.451 2"{f = 3.9

Tt4 =

3200°R

CroH

= 0.0152

h = 36 kft a = 0.4487

Tt7

= 3600°R

zrc = 20 M6 = 0.4 m0 = 200 lbm/s

Note that the bypass ratio has increased from its initial assumed value of 0.4 to

0.4487. This is mainly caused by the decreases in

"CtH

and

TtL

from their assumed

values of 0.87 (see the following).

The reference point performance of this engine at military power is summarized

next. Performance results of particular interest are

F/tho and S.

These and other

data, which are of interest because they are the cumulative result of many approxi-

mations and arguments (Sec. 5.4.3) used as guidance in the selection of the design

choices, are as follows:

F/rho

= 62.49 lbf/(lbm/s)

7rtH = 0.4231 < 0.5

zrtL = 0.4831 < 0.5

rtH = 0.8381 < 0.87

S = 1.0863 (lbm/h)/lbf

7JtL

=

0.8598 < 0.87

et6/ etl6 =

1.0

MI6 = 0.394 ,-~ M6 = 0.4

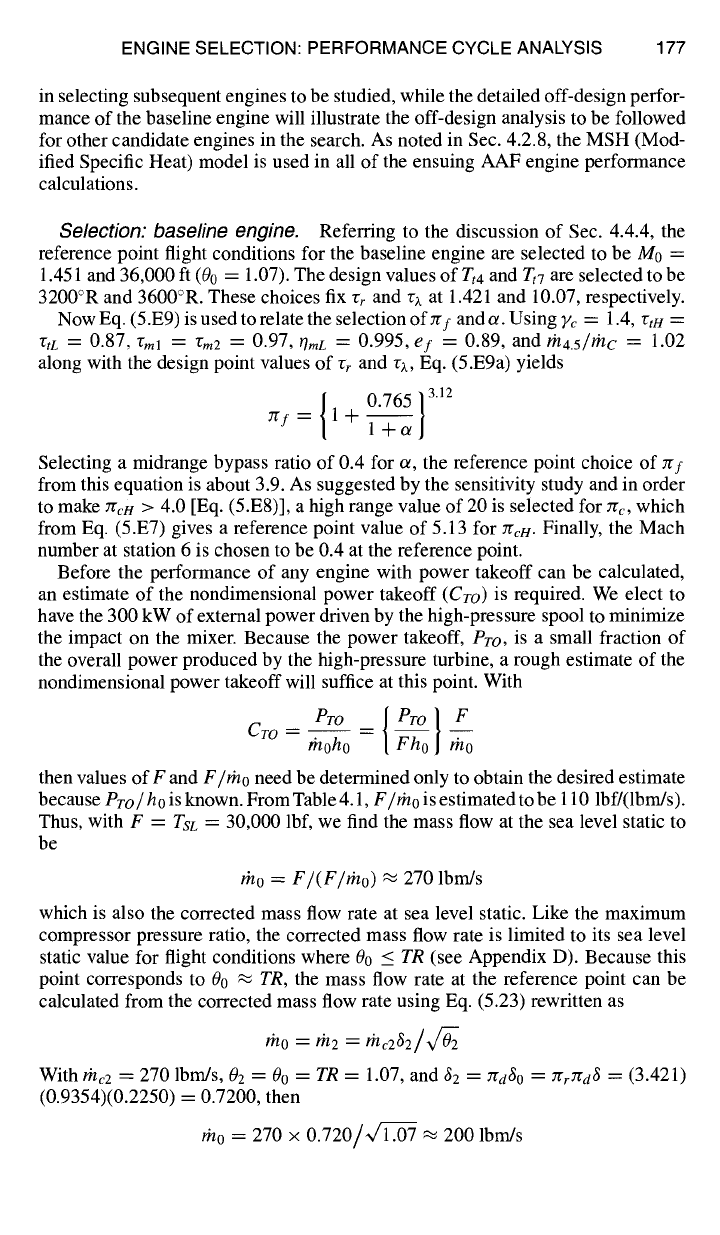

Operating envelope: baseline engine.

Before examining the performance

of the baseline engine, it is important to first ascertain the Mach number and altitude

ranges over which the engine can operate at full throttle (Tt4max with or without

afterburning), i.e., its full throttle operating envelope. It may come as a surprise at

first that an engine might not be able to operate at certain combinations of Mach

number and altitude. The full throttle Mach number and altitude operational limits

of a mixed flow turbofan engine are caused by the requirement that both the Kutta

condition (P6

= P16)

in the fixed area mixer and the power balance between the

fan plus low-pressure compressor and the low-pressure turbine (which fixes P6)

must be satisfied simultaneously. There are Mach number/altitude combinations

where both of these conditions cannot be met simultaneously, as indicated by the

inability of the Engine Test feature of the AEDsys computer program to converge

on a solution for

MI6

and]or

TtL.

To find these boundaries for the baseline engine, a performance analysis is

performed using the Engine Test feature of the AEDsys program with full throttle

ENGINE SELECTION: PERFORMANCE CYCLE ANALYSIS 179

0.90

0.80

0.70

M6

MI 6

0.60

"E tL

0.50

0.40

0.30 '

0.0

Fig. 5.El

' ' ' ' I ' ' ' ' I ' ' ' ' I ' ' ' ' I ' ' ' '

/

' ' ' r

I

, , , , I , , , , I , , , , I D , , ,

0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0

M0

Variation of

M6, M16,

and

"i'tL

for baseline engine at full throttle.

(with imposed limits of Tt4

max m_

3200°R, 7rc

max -~-

20, and T,3

max =

1660°R) over

the expected Mach number/altitude envelope of the AAE The results are shown in

Fig. 5.E 1 as the variations of M6, M]6, and rtL with Mach number at constant values

of altitude. The right endpoints in the plots are limiting operating points for the en-

gine. The values of Mach number and altitude at these points determine an engine's

operational envelope (e.g., see Fig. 5.E4) in a Mach number/altitude coordinate

system.

The results show that the baseline engine cannot operate in the high Mach/low-

altitude regime. Fortunately, this region of inoperability is outside of the AAF flight

envelope. Having established that the baseline engine is acceptable, its performance

over the critical mission legs will be examined next.

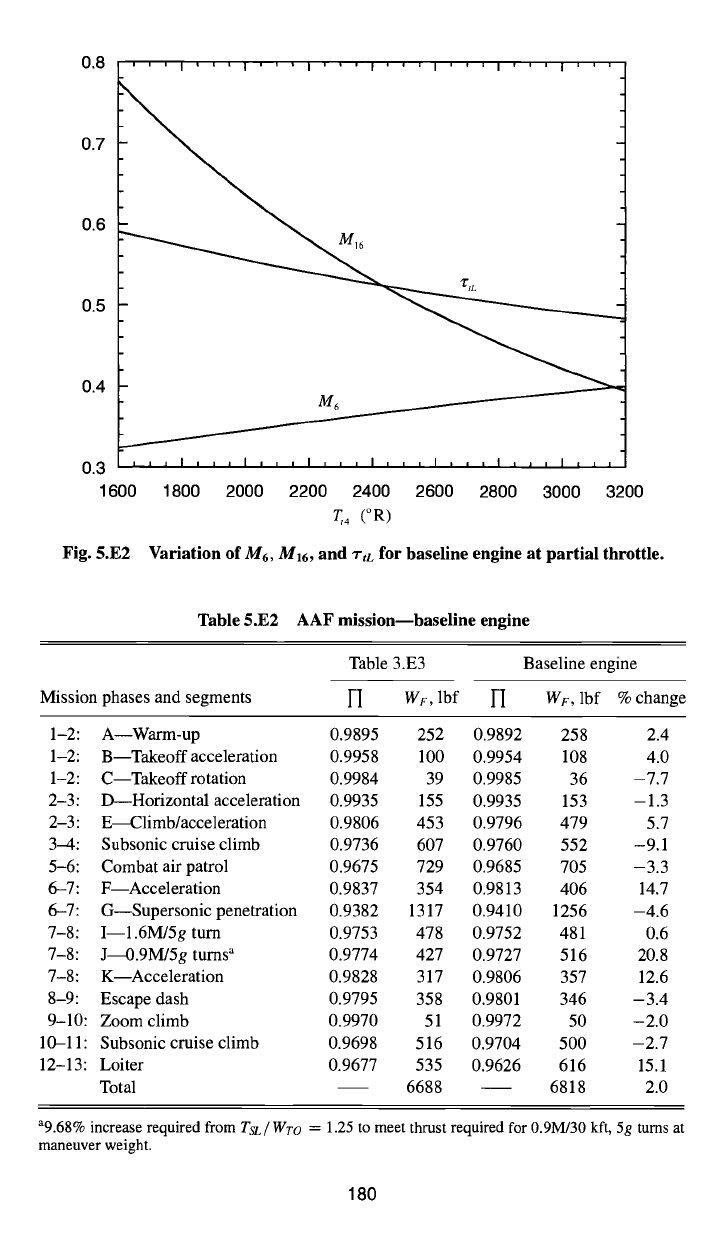

The performance of the engine at partial throttle (Tt4 < Tt4max) is also im-

portant to understand because M6, MI6, and rtc can vary far from their design

values. Figure 5.E2 shows the variation of M6,

M16,

and rtr of the baseline engine

with reduced throttle (Tt4) at 1.451M/36 kft. Note that M16 increases with reduced

throttle while M6 decreases. Thus, it is possible that as these Mach numbers di-

verge, the engine cycle deck may have trouble converging on a solution at reduced

thrott!e.

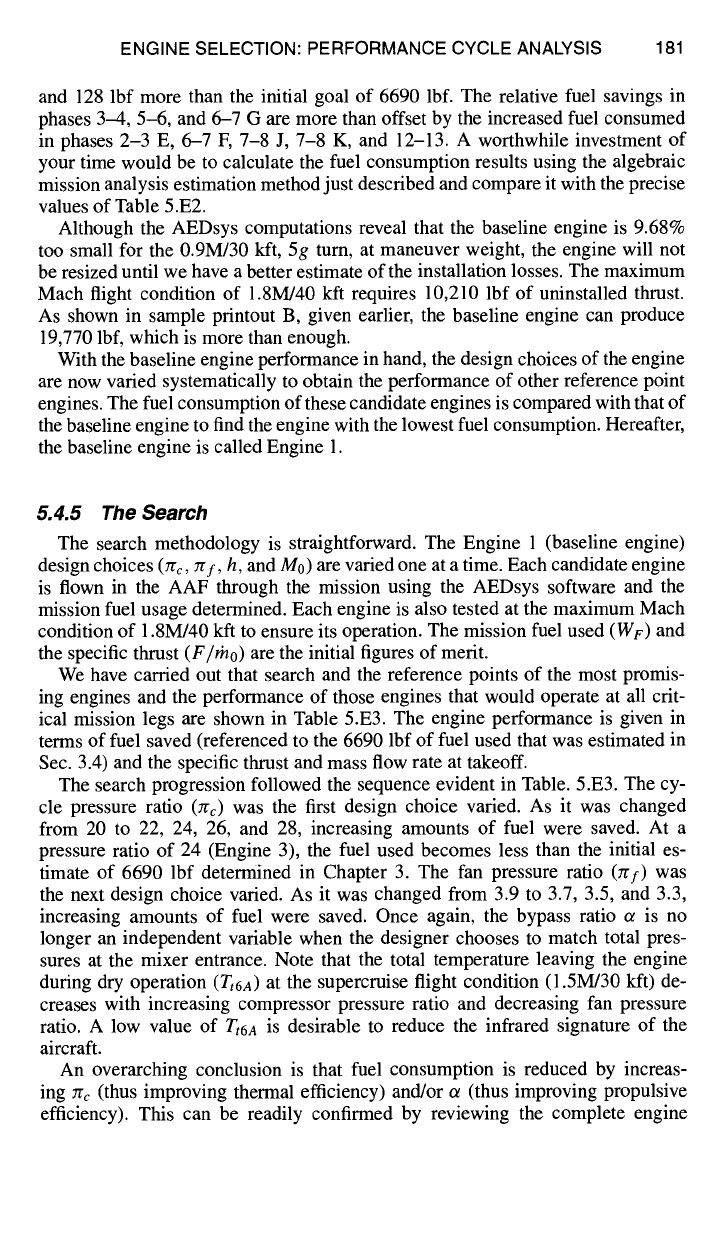

Mission performance: baseline engine. The baseline engine is now flown

through the AAF mission using the Mission Analysis portion of AEDsys. The

results of these computations are presented in Table 5.E2. The bottom line result is

an increase in fuel consumption of 130 lbf from the initial estimate of Table 3.E3,

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

' I ' I ' ' ' I ' ' ' I ' ' ' I ' ' ' I ' ' ' I ' ' ' I ' ' '

M6

,,,l,,,l,,,l,,,l,,,l,,,llliltl i

1600 1800 2000 2200 2400 2600 2800 3000 3200

~,4 (°R)

Fig. 5.E2 Variation of M6, M16, and ~-tL for baseline engine at partial throttle.

Table 5.E2 AAF mission--baseline engine

Mission phases and segments

Table 3.E3 Baseline engine

l-I WF,

lbf l--I

WF,

lbf % change

1-2: A Warm-up 0.9895 252 0.9892 258 2.4

1-2: B Takeoff acceleration 0.9958 100 0.9954 108 4.0

1-2: C--Takeoff rotation 0.9984 39 0.9985 36 -7.7

2-3: D--Horizontal acceleration 0.9935 155 0.9935 153 -1.3

2-3: E~limb/acceleration 0.9806 453 0.9796 479 5.7

3--4: Subsonic cruise climb 0.9736 607 0.9760 552 -9.1

5-6: Combat air patrol 0.9675 729 0.9685 705 -3.3

6-7: F Acceleration 0.9837 354 0.9813 406 14.7

6-7: G--Supersonic penetration 0.9382 1317 0.9410 1256 -4.6

7-8: I--1.6M/5g turn 0.9753 478 0.9752 481 0.6

7-8: J~.9M/5g turns a 0.9774 427 0.9727 516 20.8

7-8: K--Acceleration 0.9828 317 0.9806 357 12.6

8-9: Escape dash 0.9795 358 0.9801 346 -3.4

9-10: Zoom climb 0.9970 51 0.9972 50 -2.0

10-11: Subsonic cruise climb 0.9698 516 0.9704 500 -2.7

12-13: Loiter 0.9677 535 0.9626 616 15.1

Total 6688 6818 2.0

a9.68% increase required from

TsL/Wro

= 1.25 to meet thrust required for 0.9M/30 kft, 5g turns at

maneuver weight.

180

ENGINE SELECTION: PERFORMANCE CYCLE ANALYSIS 181

and 128 lbf more than the initial goal of 6690 lbf. The relative fuel savings in

phases 3-4, 5-6, and 6-7 G are more than offset by the increased fuel consumed

in phases 2-3 E, 6-7 F, 7-8 J, 7-8 K, and 12-13. A worthwhile investment of

your time would be to calculate the fuel consumption results using the algebraic

mission analysis estimation method just described and compare it with the precise

values of Table 5.E2.

Although the AEDsys computations reveal that the baseline engine is 9.68%

too small for the 0.9M/30 kft, 5g tum, at maneuver weight, the engine will not

be resized until we have a better estimate of the installation losses. The maximum

Mach flight condition of 1.8M/40 kft requires 10,210 lbf of uninstalled thrust.

As shown in sample printout B, given earlier, the baseline engine can produce

19,770 lbf, which is more than enough.

With the baseline engine performance in hand, the design choices of the engine

are now varied systematically to obtain the performance of other reference point

engines. The fuel consumption of these candidate engines is compared with that of

the baseline engine to find the engine with the lowest fuel consumption. Hereafter,

the baseline engine is called Engine 1.

5.4.5 The Search

The search methodology is straightforward. The Engine 1 (baseline engine)

design choices (Jrc, zrf, h, and M0) are varied one at a time. Each candidate engine

is flown in the AAF through the mission using the AEDsys software and the

mission fuel usage determined. Each engine is also tested at the maximum Mach

condition of 1.8M/40 kft to ensure its operation. The mission fuel used (WF) and

the specific thrust (F//no) are the initial figures of merit.

We have carried out that search and the reference points of the most promis-

ing engines and the performance of those engines that would operate at all crit-

ical mission legs are shown in Table 5.E3. The engine performance is given in

terms of fuel saved (referenced to the 6690 lbf of fuel used that was estimated in

Sec. 3.4) and the specific thrust and mass flow rate at takeoff.

The search progression followed the sequence evident in Table. 5.E3. The cy-

cle pressure ratio (Zrc) was the first design choice varied. As it was changed

from 20 to 22, 24, 26, and 28, increasing amounts of fuel were saved. At a

pressure ratio of 24 (Engine 3), the fuel used becomes less than the initial es-

timate of 6690 lbf determined in Chapter 3. The fan pressure ratio (zrf) was

the next design choice varied. As it was changed from 3.9 to 3.7, 3.5, and 3.3,

increasing amounts of fuel were saved. Once again, the bypass ratio ~ is no

longer an independent variable when the designer chooses to match total pres-

sures at the mixer entrance. Note that the total temperature leaving the engine

during dry operation

(Zt6a)

at the supercruise flight condition (1.5M/30 kft) de-

creases with increasing compressor pressure ratio and decreasing fan pressure

ratio. A low value of

Tt6 A

is desirable to reduce the infrared signature of the

aircraft.

An overarching conclusion is that fuel consumption is reduced by increas-

ing zr¢ (thus improving thermal efficiency) and/or ot (thus improving propulsive

efficiency). This can be readily confirmed by reviewing the complete engine