Kuppan T. Heat Exchanger Design Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

234

Chapter

S

access to the tubes for cleaning as required by process conditions. Four standard types of tube

layout patterns are triangular (30"), rotated triangular (60"), square

(90"),

and rotated square

(45").

(Note that the tube layout angle is defined in relation to the flow direction and is not

related to the horizontal or vertical reference line arrangement, and that the 30°,

60°,

and

45'

arrangements are "staggered," and

90"

is "in-line.") For identical tube pitch and flow rates, the

tube layouts in decreasing order of shell-side heat-transfer coefficient and pressure drop

are

30°,

45",

60°, and

90".

Thus the

90"

layout will have the lowest heat-transfer coefficient and

pressure drop. The selection of the tube layout pattern depends on the following parameters,

which influence the shell-side performance and hence the overall performance:

1.

Compactness

2.

Heat transfer

3. Pressure drop

4.

Accessibility for mechanical cleaning

5.

Phase change

if

any on the shell side

Triangular and Rotated Triangular Arrangements

Triangular and rotated triangular layouts

(30"

and 60") provide a compact arrangement, better

shell-side heat-transfer coefficients, and stronger tube sheets for a specified shell-side flow

area. For a given tube pitchloutside diameter ratio, about 15% more tubes can be accommo-

dated within a given shell diameter using these layouts

[6].

These layout patterns are satisfac-

tory for clean services, but have the disadvantage of making the lanes between tubes rather

inaccessible for mechanical cleaning. It is difficult to insert a rigid tool between the tubes.

Only chemical cleaning or water jet cleaning is possible.

Square and Rotated Square Arrangements

When mechanical cleaning is necessary on the shell side,

45"

and

90"

layouts must be used

with a minimum gap between tubes

of

6.35 mm. There is no theoretical limit to tube outer

diameter for mechanical cleaning, but the 6.35 mm clearance limits the tubes to a minimum

of

2

or

in

outer diameter

in

practice

[7].

The square pitch is generally not used in the fixed

tube-sheet design because of no need of mechanical cleaning on the shell side. These layout

patterns offer lower pressure drops and lower heat-transfer coefficients than triangular pitch.

The

45"

layout is preferred for single-phase laminar flow or fouling service, and for condensing

fluid on the shell side. Shah

121

suggests a square layout for the following applications:

1.

If the pressure drop is a constraint on the shell side, the

90"

layout is used for turbulent

flow, since in turbulent flow the

90"

has superior heat-transfer rate and

less

pressure drop.

2.

For reboilers, a square layout will be preferred for stability reasons. The

90"

layout pro-

vides vapor escape lanes.

4

BAFFLES

Baffles must generally be employed on the shell-side to support the tubes, to maintain the tube

spacing, and to direct the shell-side fluid across or along the tube bundle in a specified manner.

There are a number of different types of baffles and these may be installed in different ways

to

provide the flow pattern required for a given application.

4.1 Classification of Baffles

Baffles are either normal or parallel to the tubes. Accordingly, baffles may be classified as

transverse or longitudinal. The transverse baffles direct the shell-side fluid into the tube bundle

Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger Design

235

at approximately right angles to the tubes, and increase the turbulence of the shell fluid. Every

shell and tube exchanger has transverse baffles except the

X

and

K

shells, which have only

support plates. The longitudinal baffles are used to control the direction of the shell side flow.

For example, F,

G,

and

H

shells have longitudinal baffles. In the

F

shell,

an

overall counterflow

is achieved.

4.2

Transverse Baffles

Transverse baffles are of two types:

(1)

plate baffles and

(2)

rod baffles. Three types of plate

baffles are

(1)

segmental, (2) disk and doughnut, and

(3)

orifice baffles.

Segmental Baffles

The segmental baffle is a circular disk (with baffle holes) having a segment removed. Predomi-

nantly, a large number of shell and tube exchangers employ segmental baffles. This cutting is

denoted as the baffle cut and it is commonly expressed as a percentage of the shell inside

diameter as shown in Fig.

5.

Here the percent baffle cut is the height,

H,

given as a percentage

of the shell inside diameter,

D,.

The segmental baffle is also referred to as a single segmental

baffle. The heat transfer and pressure drop of crossflow bundles are greatly affected by the

baffle cut. The baffle cuts vary from

20

to 49% with the most common being

20-25%,

and

the optimum baffle cut is generally

20%,

as it affords the highest heat transfer for a given

pressure drop. Baffle cuts smaller than

20%

can result in high pressure drop.

As

the baffle cut

increases beyond 20%, the flow pattern deviates more and more from crossflow

[5]

and can

result in stagnant regions or areas with lower flow velocities; both of these reduce the thermal

effectiveness of the bundle

[

11.

Bane Spacing.

The practical range of single-segmental baffle spacing is to

1

shell diameter

[l],

though optimum could be 40-50%

[2].

TEMA

Table RCB-4.52

[3]

provides maximum

baffle spacing for various tube outer diameters, tube materials, and the corresponding maxi-

mum allowable temperature limit. The baffles are generally spaced between the nozzles. The

inlet and outlet baffle spacings are in general larger than the “central” baffle spacing to accom-

modate the nozzles, since the nozzle dimensions frequently require that the nozzle should be

located far enough from the tube sheets.

Figure

5

Baffle cut.

236

Chapter

5

Figure

6

Shellside

flow

distribution influenced by baffle cut,

Ref.

(13).

Bafle Thickness.

TEMA Tables

R-4.41

and

CB-4.41 [3]

provide the minimum thickness of

transverse baffles applying to all materials for various shell diameters and plate spacings.

Shell-Side Flow Distribution.

Segmental baffles have a tendency to poor flow distribution if

spacing or baffle cut ratio is not in correct proportion, as shown in Fig.

6

[13].

Too

low or

too high a ratio results in maldistribution and produces inefficient heat transfer and also favors

fouling. For low-pressure-drop designs, choose baffles that ensure a more uniform flow such

as multisegmental, disc and doughnuts, and rod baffles.

Orientation

of

Bafles.

Alternate segmental baffles are arranged at 180" to each other, which

cause shell-side flow to approach crossflow through the bundle and axial flow in the baffle

window zone. All segmental baffles shown in Fig. 7a have horizontal baffle cuts. Unless the

shell-side fluid is condensed, the horizontal baffle cut should be used for single-phase applica-

tion,

to

reduce accumulation of deposits on the bottom

of

the shell and to prevent stratification

of the shell-side fluid

[5].

The direction of the baffle cut is selected as vertical (Fig. 7b) for

the following shell-side applications

[6]:

(1)

for condensation,

to

allow the condensate

to

flow

freely to the outlet without covering an excessive amount of tubes

[2,5];

(2)

for boiling or

condensing fluids, to promote more uniform flow; and

(3)

for solids entrained in liquid (to

provide least interference for the solids to fall out).

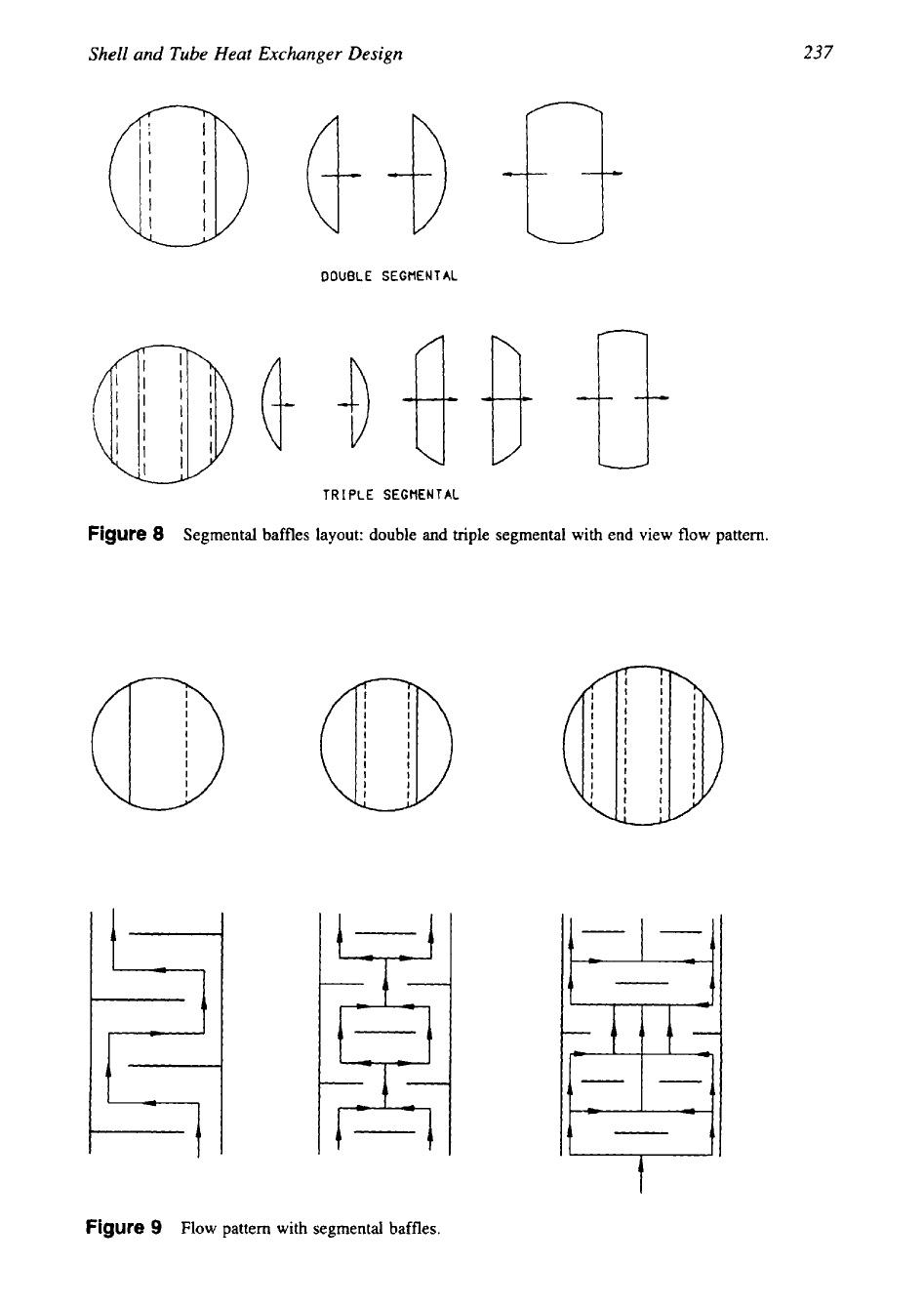

Double Segmental and Multiple Segmental

Baffles

Various multisegmental baffles can be used to reduce baffle spacing, or to reduce crossflow

because of pressure limitations. The multisegmental baffles are characterized by large open

areas and some allow the fluid to flow nearly parallel to the tubes, offering a much lower

pressure drop

[

141.

Segmental baffle layout is shown in Fig.

8

and flow distribution in Fig. 9. In an exchanger

with single segmental baffles the total flow, except for leakages and bypass streams, passes

through the tube bank between baffles in crossflow as shown in Fig. 9a, whereas with double

Figure

7

Baffle cut orientation: (a) horizontal; (b) vertical; and (c) rotated.

237

Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger Design

DOUBLE

SEGMENTAL

TRIPLE

SEGMENTAL

Figure

8

Segmental baffles layout: double

and

triple segmental with end view flow pattern.

Figure

9

Flow pattern with segmental baffles.

238

Chapter

5

segmental baffles barring the leakages, the flow divides into two streams on either side of the

shell (Fig. 9b), and in triple segmental baffles, the flow divides into three streams (Fig. 9c).

Due to this, heat exchangers with double or multiple segmental baffles can handle larger fluid

flows on the shell side. Other features of double segmental or multiple segmental baffles are

as follows [2]:

1.

The flow on the shell side is split into two or more streams as per the number of baffle

segments, namely, double, triple, multiple, etc.; hence, the danger of shell-side flow-in-

duced vibration

is

minimal.

2.

The baffle spacing should not be too small; otherwise it results in a more parallel (longitu-

dinal) flow with significant low stagnant areas.

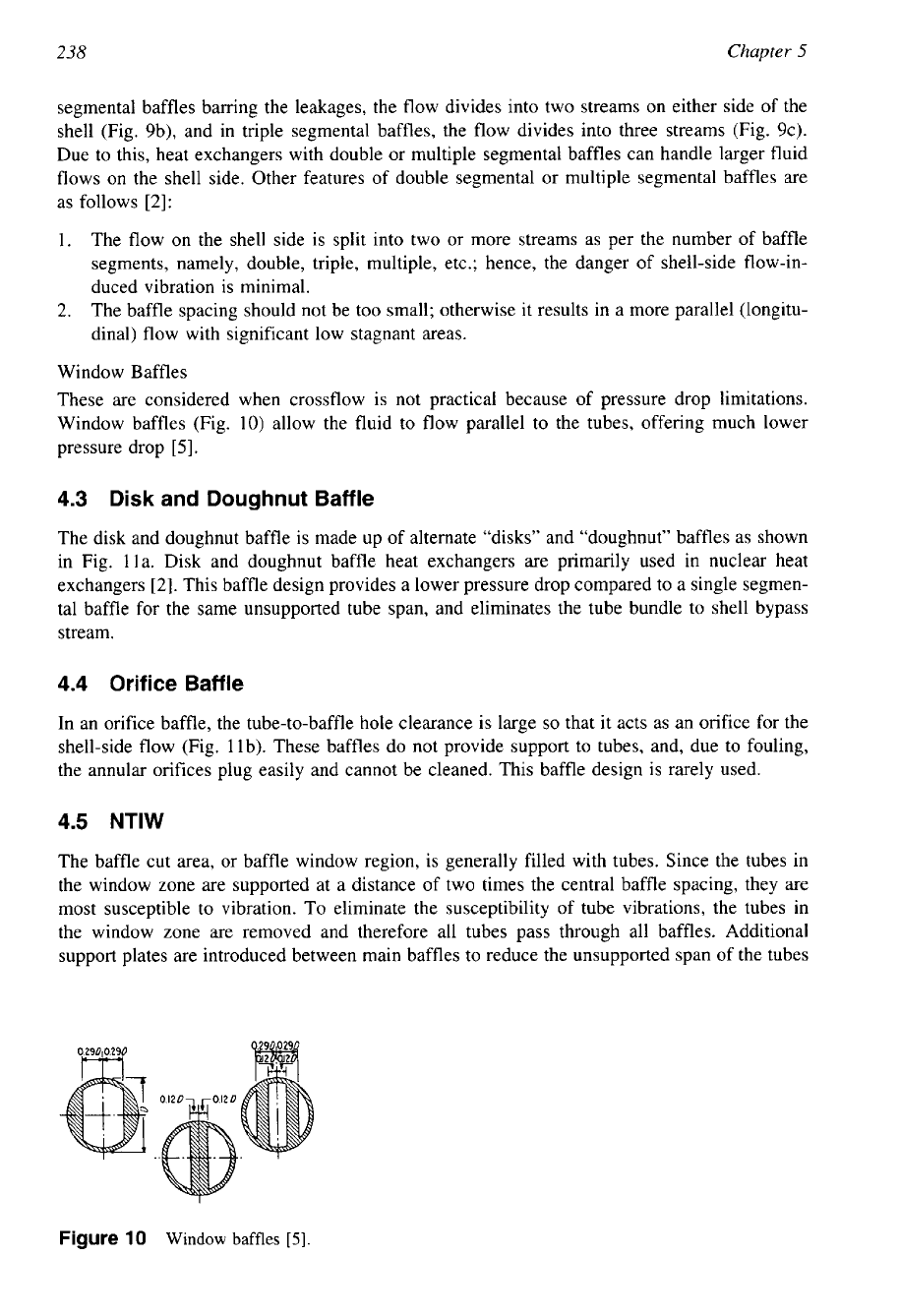

Window Baffles

These are considered when crossflow is not practical because of pressure drop limitations.

Window baffles (Fig. 10) allow the fluid to flow parallel to the tubes, offering much lower

pressure drop

[5].

4.3

Disk

and Doughnut Baffle

The disk and doughnut baffle is made up of alternate “disks” and “doughnut” baffles as shown

in Fig. lla. Disk and doughnut baffle heat exchangers are primarily used in nuclear heat

exchangers [2]. This baffle design provides a lower pressure drop compared to a single segmen-

tal baffle for the same unsupported tube span, and eliminates the tube bundle to shell bypass

stream.

4.4

Orifice Baffle

In an orifice baffle, the tube-to-baffle hole clearance is large

so

that it acts as an orifice for the

shell-side flow (Fig. llb). These baffles do not provide support to tubes, and, due to fouling,

the annular orifices plug easily and cannot be cleaned. This baffle design is rarely used.

4.5

NTlW

The baffle cut area, or baffle window region, is generally filled with tubes. Since the tubes in

the window zone are supported at a distance of two times the central baffle spacing, they are

most susceptible to vibration. To eliminate the susceptibility of tube vibrations, the tubes in

the window zone are removed and therefore all tubes pass through all baffles. Additional

support plates are introduced between main baffles to reduce the unsupported span of the tubes

Figure

10

Window

baffles

[5].

239

Shell and Tube Heat Exchanger Design

orifice

baffles

,

f

Disk

4

Doughnut

2

Disk

Figure

11

Nonsegmental

circular

baffles. (a)

Orifice

baffle, and (b) disk and doughnut

baffles.

as shown in Fig.

12,

thus providing an increase in the natural frequency of the tubes. The

resultant design is referred to as the segmental baffle with no-tubes-in-window

(NTIW)

design.

NTIW

design has the following characteristics

[

151:

1.

Pressure drop about one-third that

of

single segmental baffle design.

2.

Uniform shell-side flow pattern resembling that of an ideal tube bank, which offers high

shell-side heat-transfer coefficient and low fouling tendency.

Figure

12

No

tube in window design

(NTIW).

240

Chapter

5

3.

The baffle cut and number of tubes removed varies from 15 to

25%.

4.

Very low pressure drop

in

the window and correspondingly lower bypass and leakage

streams.

Since the loss

in

heat transfer surface is considerable in an

NTIW

design, this can ba

minimized by having small baffle cuts and possibly by

an

increase

in

the shell-side fluid

velocity or larger shell diameter to contain the same number of tubes.

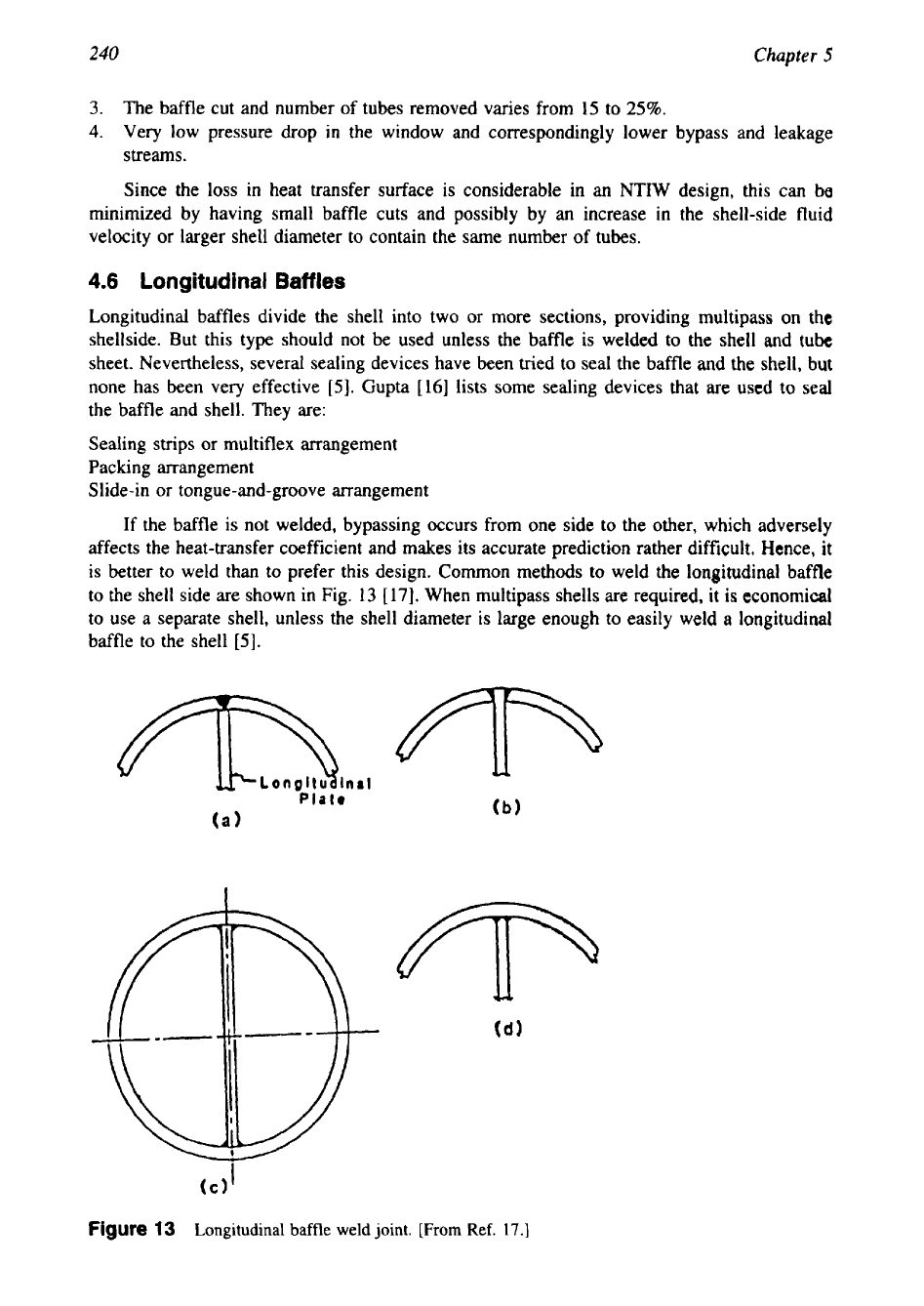

4.6

Longitudinal

Baffles

Longitudinal baffles divide the shell into two or more sections, providing multipass on the

shellside. But this type should not be used unless the baffle is welded to the shell and

tube

sheet. Nevertheless, several sealing devices have been tried to seal the baffle and the shell, but

none has been very effective [5]. Gupta [16] lists some sealing devices that

are

used to seal

the baffle

and

shell. They are:

Sealing strips or multiflex arrangement

Packing arrangement

Slide-in or tongue-and-groove arrangement

If the baffle is not welded, bypassing occurs from one side to the other, which adversely

affects the heat-transfer coefficient and makes its accurate prediction rather difficult. Hence, it

is better

to

weld than to prefer this design. Common methods to weld the longitudinal baffle

to the shell side are shown

in

Fig. 13 [17]. When multipass shells are required, it

is

economical

to use a separate shell, unless the shell diameter is large enough to easily weld

a

longitudinal

baffle to the shell [5].

I

(C)

Figure

13

Longitudinal

baffle

weld joint.

[From

Ref.

17.1

241

Shell and

Tube

Heat Exchanger Design

h

A

A

TYP

for

alt

strip

to

ring

junctions

slde

Figure

14

Special types of plate baffles. (a)

NESTTM;

and

(b) egg-crate baffle support.

4.7

Rod Baffles

Phillips RODbaffle design uses alternate sets of rod grids instead

of

plate baffles, enabling the

tubes to be supported at shorter intervals without resulting in a large pressure drop. Flow-

induced vibration is virtually eliminated by this design. The flow is essentially parallel to tube

axis; as

a

result of the longitudinal flow, it has low pressure drop to heat transfer conversion

characteristics. The tube layout is usually

45"

or

90".

Design

of

rod baffle heat exchanger

is

covered separately.

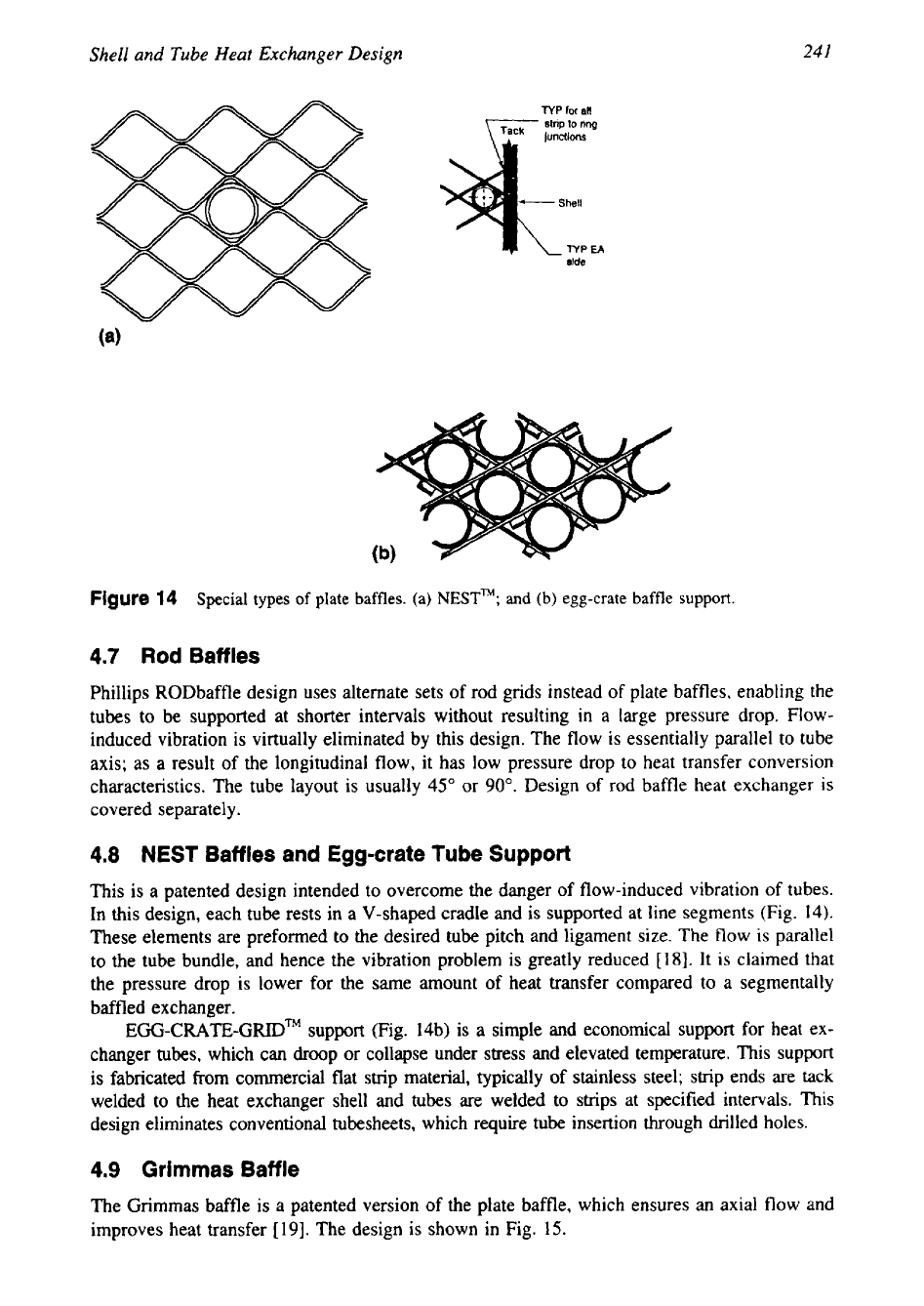

4.8

NEST

Baffles

and

Egg-crate Tube Support

This is a patented design intended to overcome the danger of flow-induced vibration of tubes.

In this design, each tube rests in a V-shaped cradle and is supported at line segments (Fig.

14).

These elements are preformed to

the

desired tube pitch and ligament size. The flow

is

parallel

to the tube bundle, and hence the vibration problem

is

greatly reduced

[

181.

It is claimed that

the pressure drop is lower for the same amount

of

heat transfer compared to a segmentally

baffled exchanger.

EGG-CRATE-GRIDTM

support (Fig. 14b) is

a

simple and economical support for heat ex-

changer tubes, which can droop or collapse under stress and elevated temperature. This support

is fabricated from commercial flat strip material, typically of stainless steel; strip ends are tack

welded to the heat exchanger shell and tubes are welded to strips at specified intervals. This

design eliminates conventional tubesheets, which require tube insertion through drilled holes.

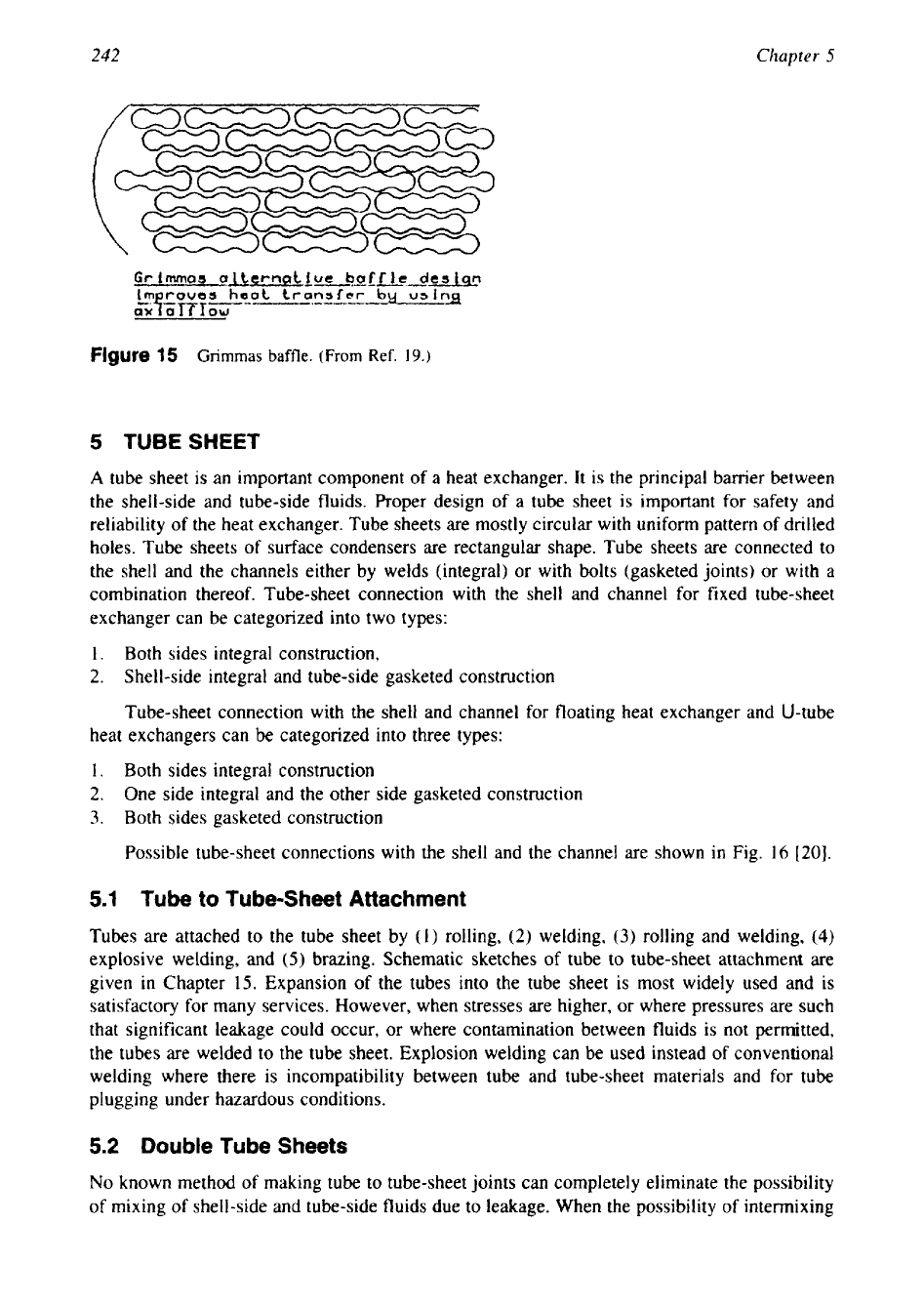

4.9

Grimmas Baffle

The Grimmas baffle is a patented version of the plate baffle, which ensures

an

axial

flow

and

improves heat transfer

[19].

The design is shown in Fig.

15.

242

Chapter

5

Figure

15

Grimmas

baffle. (From

Ref.

19.)

5

TUBESHEET

A

tube sheet is an important component of a heat exchanger. It is the principal barrier between

the shell-side and tube-side fluids. Proper design of a tube sheet is important

for

safety and

reliability of the heat exchanger. Tube sheets are mostly circular with uniform pattern of drilled

holes. Tube sheets of surface condensers are rectangular shape. Tube sheets are connected to

the shell and the channels either by welds (integral)

or

with bolts (gasketed joints)

or

with a

combination thereof. Tube-sheet connection with the shell and channel for fixed tube-sheet

exchanger can be categorized into two types:

1. Both sides integral construction,

2.

Shell-side integral and tube-side gasketed construction

Tube-sheet connection with the shell and channel for floating heat exchanger and U-tube

heat exchangers can be categorized into three types:

1.

Both sides integral construction

2.

One side integral and the other side gasketed construction

3.

Both sides gasketed construction

Possible tube-sheet connections with the shell and the channel are shown in Fig.

16

[20].

5.1

Tube to Tube-Sheet Attachment

Tubes are attached to the tube sheet by

(1)

rolling,

(2)

welding,

(3)

rolling and welding,

(4)

explosive welding, and

(5)

brazing. Schematic sketches of tube to tube-sheet attachment are

given

in

Chapter

15.

Expansion

of

the tubes into the tube sheet is most widely used and is

satisfactory for many services. However, when stresses are higher,

or

where pressures are such

that significant leakage could occur, or where contamination between fluids is not permitted,

the tubes are welded to the tube sheet. Explosion welding can be used instead of conventional

welding where there

is

incompatibility between tube and tube-sheet materials and

for

tube

plugging under hazardous conditions.

5.2

Double Tube Sheets

No

known method

of

making tube to tube-sheet joints can completely eliminate the possibility

of mixing

of

shell-side and tube-side fluids due to leakage. When the possibility

of

intermixing

243

Shell and

Tube

Heat Exchanger Design

Figure

16

Tubesheet connection

with

shell and channel. (Note:

2

and

4

refer to

fixed

tubesheet design.)

of the shell-side and tube-side fluids cannot

be

tolerated, double tube-sheet construction will

offer positive assurance against one fluid leaking into the other at a tube to tube-sheet joint.

Types of Double Tube-Sheets Designs

Two designs of double tube sheets are available:

(I)

the conventional double tube sheet design,

which consists of two individual tube sheets at each end of the tubes, and

(2)

the integral

double tube-sheet design

[2

I].

Conventional Double Tube Sheet Design

In a conventional double tube-sheet design, the tube sheets are installed with a small space

between them. The space is usually open to the atmosphere. Sometimes a thin strip is welded

to avoid ingress of dusts and dirt, or an expansion joint

is

welded with vent at the top and a

drain at the bottom. These patterns are shown in Fig.

17.

While selecting material for double

tubesheet design, the outer tubesheet should be compatible with the tubeside fluid and the

inner tubesheet should be compatible with the shellside fluid. The most important consideration

is the differential radial expansion

of

the two tubesheets which will stress the tubes. The double

tube sheet can be installed only in the U-tube, fixed tube sheet, and floating head, outside

packed stuffing box exchangers. It is not feasible to use the double tube sheet in heat exchanger

types such as

[4]

(1)

floating head, pull-through bundle,

(2)

floating head with split backing

ring, and

(3)

floating head, outside packed lantern ring exchangers. An expression for the space

between the tubesheets pairs,

l,,

which is widely used in the industry

is

a special case of the

more complex analysis of Urgami et al.

[22].

The expression is given by [21]: