Krishnamurti Bhadriraju. The Dravidian Languages

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Appendix:

Noun paradigms

in individual

languages

271

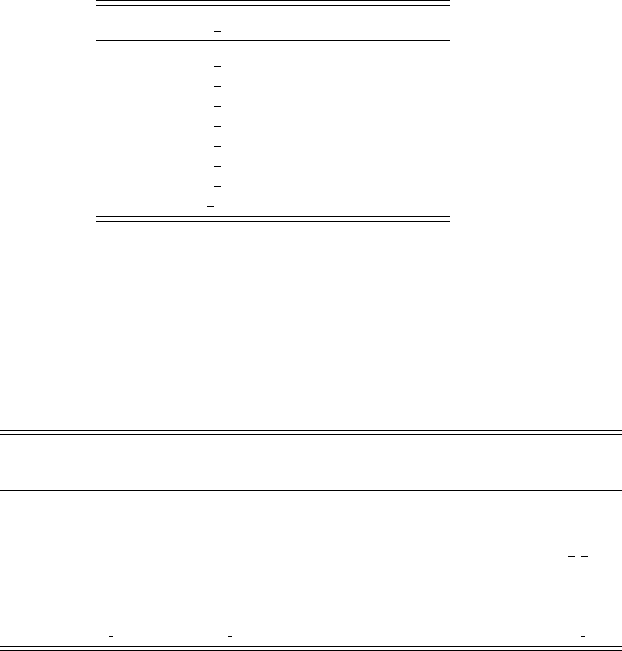

1b. Modern Tamil (Asher 1982: 103)

payyan ‘boy’ maram ‘tree’

Nom payyan maram

Acc payya

n-e mara-tt-e

Dat payya

n-ukku mara-tt-ukku

Instr payya

n-¯ale mara-tt-¯ale

Com payya

n-¯o

.

te mara-tt-¯o

.

te

Loc payya

n-ki

.

t

.

te mar-tt-ile

Abl payya

n-ki

.

t

.

t-eruntu mara-tt-il-eruntu

Gen paya

n(¯o

.

ta) mara-ttu

The difference between the two nouns in the locative and ablative arises from the difference in the

feature of [± animate].

2. Malay¯a

.

lam (Asher and Kumari 1997: 191–4)

Stems

Case Marker ‘son’ ‘daughter’ ‘boy’ ‘tree’

Nom ø makan maka

.

lku

.

t

.

tika

.

l maram

Acc -e makan-e maka

.

l-e ku

.

t

.

tila

.

l-e maratt-e

Dat -kk

ə

/-(n)

ə

makan-n

ə

maka

.

l-kk

ə

ku

.

t

.

tika

.

l-kk

ə

maratt-i

n-n

ə

/-n

ə

Soc -¯o

.

t

ə

makan-¯o

.

t

ə

maka

.

l-¯o

.

t

ə

ku

.

t

.

tika

.

l-o

.

t

ə

mara-tt-¯ot

ə

Loc -il makan-il maka

.

l-il ku

.

t

.

tika

.

l-il mara-tt-il

Instr -¯al makan-¯al maka

.

l-¯al ku

.

t

.

tika

.

l-¯al mar-tt-¯al

Gen -u

.

te/-

re makan-re maka

.

l-u

.

te ku

.

t

.

tika

.

l-u

.

te mara-tt-inre

272 Nominals

3. Ko

.

dagu (Ebert 1996: 30–1)

akk¨em¯ova m¯u

.

di mane mara

‘elder sister’ ‘daughter’ ‘girl’ ‘house’ ‘tree’

Singular

Nom akk¨em¯ova m¯u

.

di mane mara

Dat akk¨en-g¨ım¯ova-k¨ım

.

t

.

di-k¨ı mane-k¨ı mara-k¨ı

Acc akk¨en-a m¯ova

.

l-a m¯u

.

di-na mane-na marat¨ı-na

Gen akk¨en-

.

da m¯ova-

.

da m¯u

.

di-ra mane-ra marat¨ı-ra

Loc – – – mane-l¨ı marat¨ı-l¨ı

Abl – – – mane-nja marat¨ı-nja

Plural

Nom akk¨en-ga m¯ole-ya m¯u

.

di-ya

Dat akk¨en-ga-k¨ım¯ole-ya-k¨ım¯u

.

di-ya-k¨ı

Acc akk¨en-ga

.

l-a m¯ole-ya

.

l-a m¯u

.

di-ya

.

l-a

Gen akk¨en-ga-

.

da m¯ole-ya-

.

da m¯u

.

di-ya-

.

da

4. Kanna

.

da (Steever 1998 based on Sridhar 1990)

mara ‘tree’ mane ‘house’ hu

.

duga ‘boy’

Singular

Nom mara mane hu

.

duga

Obl mara-d- mane- hu

.

duga-n-

Acc marav-annu maney-annu hu

.

duga-n-annu

Dat mara-kke mane-ge hu

.

duga-n-ige

Gen mara-d-a maney-a hu

.

duga-n-a

Loc mara-d-alli maney-alli hu

.

duga-n-alli

Abl mara-d-inda maney-inda hu

.

dugan-inda

Plural

Nom mara-ga

.

lu mane-ga

.

lu hu

.

duga-ru

Acc mara-ga

.

l-annu mane-ga

.

l-annu hu

.

duga-r-annu

Dat mara-ga

.

l-ige mane-ga

.

l-ige hu

.

duga-r-ige

Gen mara-ga

.

l-a mane-ga

.

l-a hu

.

duga-r-a

Loc mara-ga

.

l-alli mane-ga

.

l-alli hu

.

duga-r-alli

Abl mara-ga

.

l-inda mane-ga

.

l-inda hu

.

duga-r-inda

Appendix:

Noun paradigms

in individual

languages

273

5. Tu

.

lu (Bhat 1998: 164)

mara ‘tree’ mage ‘son’ kall¨ı ‘stone’ p¯u ‘flower’

Singular

Nom mara mage kall¨ıp¯u

Acc mara-n¨ı maga-n¨ı kall¨ı-n¨ıp¯u-nu

Dat mara-k¨ı maga-k¨ı kall¨ı-g¨ıp¯u-ku

Abl mara-

.

dd¨ımaga-

.

dd¨ı kall¨ı-

.

dd¨ıp¯u-

.

ddu

Loc 1 mara-

.

t¨ı maga-t¨ı kall¨ı-

.

d¨ıp¯u-

.

tu

Loc 2 mara-

.

tε – kall¨ı-

.

dε p¯u-

.

tε

Soc mara-

.

ta maga-

.

ta kall¨ı-

.

da p¯u-

.

ta

Gen mara-ta maga-na kall¨ı-da p¯u-ta

Plural

Nom mara-kulu maga-llu kallu-lu p¯u-kulu

Acc mara-kul-e-n¨ı maga-ll-e-n¨ı kall¨ı-l-en¨ıp¯u-kul-e-n¨ı

Dat mara-kul-e-g¨ı maga-ll-e-k¨ı kall¨ı-l-e-g¨ıp¯u-kul-e-g¨ı

Abl mara-kul-e-

.

dd¨ı maga-ll-e-

.

dd¨ı kall¨ı-l-e-

.

dd¨ıp¯u-kul-e-

.

dd¨ı

Loc 1 mara-kul-e-

.

d¨ı maga-ll-e-

.

d¨ı kall¨ı-l-e-

.

d¨ıp¯u-kul-e-

.

d¨ı

Loc 2 mara-kul-e-

.

dε – kall¨ı-l-e-

.

dε p¯u-kul-e-

.

dε

Soc mara-kul-e-da maga-ll-e-

.

da kall¨ı-l-e-

.

da p¯u-kul-e-

.

da

Gen mara-kul-e-na maga-ll-e-na kall¨ı-l-e-na p¯u-kul-e-na

In the plural -e is the oblique marker uniformly.

274 Nominals

South Dravidian II

6. Modern Telugu (Krishnamurti and Gwynn 1985)

bomma ‘doll’ tammu

.

du ‘younger brother’ illu ‘house’

Singular

Nom bomma tammu

.

du illu

Obl–Gen bomma -ø tammu

.

d-i i

.

n-

.

ti

Acc bomm-ø/-nu tammu-

.

n

.

ni i

.

n-

.

ti-ni

(← tammu

.

di-ni)

Dat bomma-ku tammu

.

d-i-ki i

.

n-

.

ti-ki

Instr–Soc bomma-t¯o tammu

.

d-i-t¯oi

.

n-

.

ti-t¯o

Abl bomma-ninci tammu

.

n-nunci/-ninci i

.

n-

.

ti-nunci/-ninci

Loc bomma-l¯o tammu

.

l-

.

l¯oi

.

n-

.

t(i)-l¯o

(← tammu

.

d-i-l¯o)

Plural bomma-lu tammu

.

l-

.

lu i

.

n

.

d-

.

lu/i

.

l-

.

lu

‘dolls’ ‘younger brothers’ ‘houses’

Nom bomma-lu tammu

.

l-

.

lu i

.

n

.

d-

.

lu/i

.

l-

.

lu

Obl–Gen bomma-l-a tammu

.

l-

.

l-a i

.

n

.

d-

.

l-a/i

.

l-

.

l-a

Acc bommalu/ tammu

.

l-

.

l-a-nu i

.

n

.

d-

.

lu/i

.

l-

.

lu (or)

bomma-l-(a)-nu i

.

n

.

d-

.

l-a-nu/i

.

l-

.

l-a-nu

Dat bomma-l-a-ku tammu

.

l-

.

l-a-ku i

.

n

.

d-

.

l-a-ku/i

.

l-

.

l-a-ku

Instr–Soc bomma-l-a-t¯o tammu

.

l-

.

l-a-t¯oi

.

n

.

d-

.

l-a-t¯o/i

.

l-

.

l-a-t¯o

Abl bomma-l-a-nunci tammu

.

l-

.

l-a-nunci i

.

n

.

d-

.

l-a-nunci/i

.

l-

.

l-a-nunci

Loc bomma-l-(a)-l¯o tammu

.

l-

.

l-a-l¯oi

.

n

.

d-

.

l-a-l¯o/i

.

l-

.

l-a-l¯o

7. Ko

.

n

.

da (Krishnamurti 1969a: 261–4)

Stem Oblique Acc–Dat Instr–Abl Loc

kiyu ‘hand’ kiyu-di kiyu-di-

ŋ

kiyu-d-a

.

n

.

dk¯ı-du

n¯a

ru ‘village’ n¯aru-di n¯aru-di-

ŋ

n¯a

r-d-a

.

n

.

dn¯a-

.

to

s¯alam ‘cavw’ s¯alam-ti s¯alam-ti-

ŋ

s¯alam-t-a

.

n

.

ds¯alam-i

In the plural the use of instrumental–ablative is rare.

Appendix:

Noun paradigms

in individual

languages

275

8. Kui (Winfield 1928: 25–8)

¯aba ‘father’ aja ‘mother’ k¯oru ‘buffalo’

Singular

Nom ¯aba aja k¯oru

Gen ¯aba aja-ni k¯oru

Acc ¯aba-i aja-ni-i k¯oru-tin-i

Dat ¯aba-ki aja-n-gi k¯oru tin-gi

Ass ¯aba-ke aja-n-ge –

Abl ¯aba + aja-ni + k¯oru +

Plural

Nom ¯aba-ru aja-ska k¯or-ka

Gen ¯aba-r-i aja-ska-ni k¯or-ka

Acc ¯aba-r-i-i aja-ska-ni-i k¯or-ka-tin-i

Dat ¯aba-r-i-ki aja-ska-n-gi k¯or-ka-tin-gi

Assoc ¯aba-r-i-ke aja-ska-n-ge –

Abl ¯aba-r-i + aja-ska-ni + k¯or-ka +

Winfield gives a long list of postpositions that occur in the ablative. The appropriate one is to be

chosen in declension.

Central Dravidian

9. Ollari (Bhattacharya 1957: 25)

aba ‘father’ ¯enig ‘elephant’

Singular Plural Singular Plural

Nom aba aba-r ¯enig ¯eng-il

Acc aba-n/-

ŋ

aba-r-an/-a

ŋ

¯eng-in ¯eng-il-in

Instr aba-n¯al aba-r-n¯al ¯enig-n¯al ¯eng-il-n¯al

Dat aba-payi

.

t aba-r-payi

.

t¯enig-payi

.

t¯eng-il-payi

.

t

Abl aba-

.

tu

ŋ

aba-r-

.

tu

ŋ

¯enig-

.

tu

ŋ

¯eng-il-

.

tu

ŋ

Gen aba-n aba-r-in ¯eng-in ¯eng-il-in

Loc aba-tun aba-r-tun ¯enig-tin ¯eng-il-tin

276 Nominals

North Dravidian

10. Ku

.

rux (Hahn 1911: 15)

Masculine: ¯al, ¯alas ‘man’

Singular Plural

Nom ¯al, ¯al-as ¯al-ar

Gen ¯al, ¯al-as gahi ¯al-ar gahi

Dat ¯al, ¯al-as-g¯e¯al-ar-g¯e

Acc ¯al-an, ¯al-as-in ¯al-ar-in

Abl ¯al-t¯ı, ¯al-as-t¯ı¯al-ar-t¯ı, ¯al-ar-int¯ı

Instr ¯al-tr¯ı, ¯al-as-tr¯ı¯al-ar-tr¯ı, ¯al-ar-tr¯u

Loc ¯al-n¯u, ¯al-as-n¯u¯al-ar-n¯u

Feminine: mukk¯a ‘woman’

Singular Plural

Nom mukk¯a mukka-r

Gen mukk¯a gahi mukka-r gahi

Dat mukk¯a-g¯e mukka-r-g¯e

Acc mukka-n mukka-r-in

Abl mukka-n-t¯ı mukka-r-t¯ı, mukka-r-in-t¯ı

Instr mukk¯a-tr¯ı, -tr¯u mukka-r-tr¯ı, mukka-r-tr¯u

Loc mukk¯a-n¯u mukka-r-n¯u

Neuter: all¯a ‘dog’

Singular Plural

Nom all¯a all¯agu

.

thi

Gen all¯a gahi all¯agu

.

thi gahi

Dat all¯a-g¯e all¯agu

.

thi-g¯e

Acc alla-n all¯agu

.

thi-in

Abl all¯a-t¯ı, alla-n-t¯ı all¯agu

.

thi-t¯ı, -in-t¯ı

Instr all¯a-tr¯ı, -tr¯u all¯agu

.

thi-tr¯ı, -tr¯u

Loc all¯a-n¯u all¯agu

.

thi-n¯u

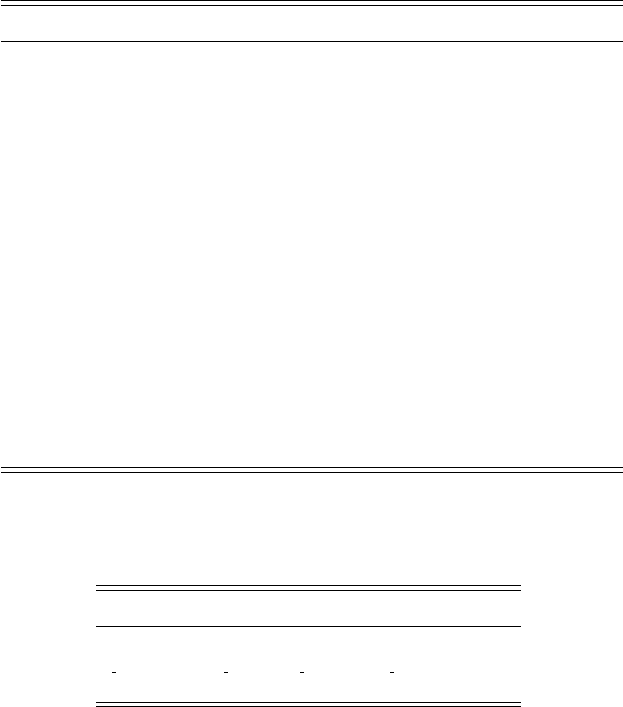

11. Brahui (Bray 1909: 43)

xar¯as ‘bull’

Singular Plural

Nom xar¯as xar¯as-k

Gen xar¯as-n-¯a xar¯as-t-¯a

Dat–Acc xar¯as-e xar¯as-te

Abl xar¯as-¯an xar¯as-te-¯an

Instr xar¯as-a

.

t xar¯as-te-a

.

t

Conj xar¯as-to xar¯as-te-to

Loc xar¯as-

.

t¯ı ‘in ...’ xar¯as-t¯e-

.

t¯ı

xar¯as-¯ai ‘on ...’ xar¯as-te-¯ai

7

The verb

7.1 Introduction

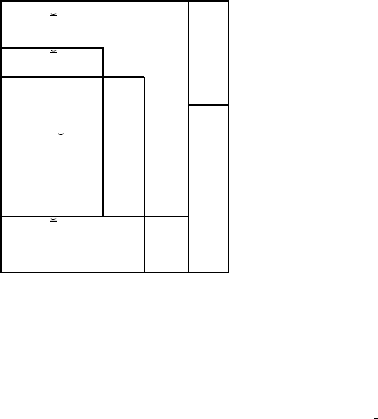

It has been pointed out that Dravidian roots are monosyllabic, of eight canonical forms,

which can be conflated into the formula (C)

˘

¯

V(C), i.e. V, CV, VC, CVC;

¯

V, C

¯

V,

¯

VC, C

¯

VC.

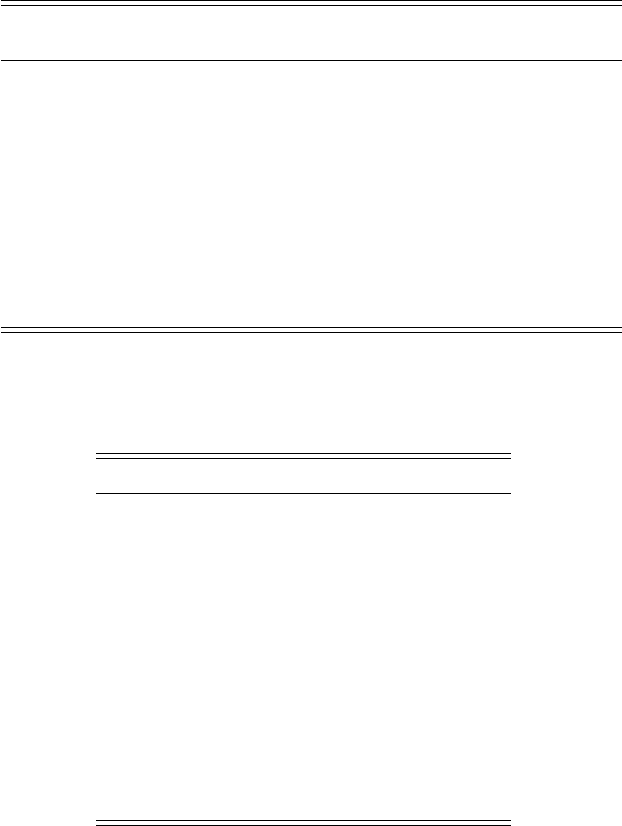

In terms of the phonotactics of Dravidian, a total of 1,496 roots can be reconstructed for

Proto-Dravidian (section 5.1). These may be optionally followed by formative suffixes

of the type -V, -VC, -VCC, or -VCCC. The details can be captured by the diagram in

figure 7.1.

A Dravidian root, of whatever part of speech, may be:

(a) An open syllable, i.e. V, CV,

¯

V, C

¯

V followed either by a Ø formative or one of the

formatives of the shape L (sonorant), stop (P), geminate stop (PP), nasal + homorganic

stop (NP), or a nasal + a geminate homorganic stop (NPP), e.g.

∗

o- ‘to suit’ [924],

∗

¯a-

‘to be, become’ [333],

∗

po- ‘to perforate’ [4452], po-k-/po-t - ‘to make a hole’ [4348],

∗

p¯u n. ‘flower’, v.i. ‘to flower’ [4348],

∗

k¯a/

∗

k¯a-n/

∗

k¯a-

.

tu ‘forest’ [1418, 1438].

(b) A closed syllable, i.e. VC, CVC,

¯

VC, or C

¯

VC without further accretions, e.g.

∗

oy ‘to carry’ [984],

∗

key ‘to do’,

∗

¯a

.

t-u ‘to dance’ [347],

∗

k¯al ‘leg’ [1479]. There is

reason to believe that there are some roots of (C)VCC- type contrasting with (C)VC-

which prosodically belong to this slot. Some of the roots of

˘

¯

VC and C

˘

¯

VC type may have

been originally open-syllabled roots like (a) with the final consonant being historically

a formative (cf. DEDR 4452, 4348, and 1418, 1438 above). The etymological boundar

y

in such forms would be

˘

¯

V-C, C

˘

¯

V-C.

(c) The closed syllable roots with a short vowel

1

may be further extended by formatives

in two layers: V

2

= /i u a/. It is not possible to assign any meaning to these vowels, but

they are detachab

le on structural and etymological grounds; V

2

may be followed by the

above suffixes, i.e. L, P, PP, NP, NPP as a second layer, e.g.

∗

na

.

t-a ‘to walk’ [3582],

∗

par-a

‘to spread’ [3949],

∗

p¯er/

∗

per-V- ‘big’ [4411],

∗

mar-a-n ‘tree’, al-a-nk- ‘to shake’, etc.

(d) There is one class of exceptions to (c) indicated in the last row, i.e. some nasal-

ending roots may be followed by P or PP. In other words, in such stems the etymological

1

A (C)

¯

VC type root becomes (C)VC when a vowel formative follows (see section 4.3.3.2).

278 The verb

# (C

1

)V

1

C

2

# (C

1

)V

1

# (C

1

)V

1

C

2

# (C

1

)V

1

N

V

L

Ø

(u)#

u #

P

PP

P

PP

NP

NPP

Figure 7.1 Structure of Proto-

Dravidian roots and stems (same as

4.1)

boundary is N-P, N-PP where N belongs to

˘

¯

V

1

of the root, e.g

∗

en-t- ‘sun’ [869],

∗

e

.

n-

.

t

.

t-

‘eight’ [784],

∗

w¯e

.

n-

.

tu ‘to wish’ [5528].

If the base ends in a P it is followed by a non-morphemic

∗

-u obligatorily. However, this

is optional if the last segment is a sonorant (L). The number of possible roots (primary

and extended) increases as we proceed from open-syllable roots to closed syllables,

i.e. (C)

˘

¯

VC > (C)

˘

¯

V and monosyllabic to disyllabic

(C)VC-V-

> (C)VC- (see section

5.1). Actually the roots of the (C)V- type are rare, e.g. PD

∗

o-: Ta. o-(-pp-, -tt-) [924];

most other languages have cognates with

incorporated suf

fixes (see

section 5.4.). A root

in Dravidian can be morphosyntactically a noun or a verb or an adjective, e.g.

∗

¯a ‘to

become’ [333],

∗

¯a ‘cow’ [334],

∗

¯ı ‘fly’ [533],

∗

p¯ı ‘excrement’ [4210],

∗

p¯u n. ‘flower’, v.

‘to flower’ [4348],

∗

p¯er/

∗

per-V- ‘big’ [4411],

∗

p¯o ‘to go’ [4572],

∗

n¯ı ‘to abandon’

[3685],

∗

m¯a ‘animal, beast, deer’ [4780],

∗

n¯o ‘to suffer’ [3793],

∗

n¯u ‘sesame seed’

[3720]. From the canonical structure we cannot predict the part of speech of a given

root. It has been demonstrated with adequate evidence that, in disyllabic and trisyllabic

stems with extended formative suffixes, these suffixes (-V-L, -V-P, -V-NP, -V-PP, -V-NPP)

were originally markers of tense and voice in Early Proto-Dravidian. They gradually lost

the tense meaning first and later the voice meaning, thereby becoming mere formatives

(see chapter 5).

7.2 The verbal base

Synchronically, a verbal base (root with or without formatives) is said to be identified

by its form in the imperative singular (Caldwell 1956: 446), e.g. w¯a ‘come’, koy ‘cut’

in most languages. This is not always true, Telugu and Ko

.

n

.

da r¯a (<

∗

wr¯a- <

∗

war-a-)

‘come’ is a suppletive in imperative singular and plural: Te. r¯a imper. 2sg, r¯a-

.

n

.

di 2pl,

7.3 Intr

ansitive, t

ransitive and causative

stems

279

Ko

.

n

.

da ra-

ʔ

a 2sg, ra-du 2pl. A verb in Dravidian is inflected for tense/aspect/mood and

carries a verbal base as its nucleus. A verbal base in Dravidian may be simple, complex

or compound. A simple base is identical to the monosyllabic verb root (C

1

)

˘

¯

V(C

2

),ora

disyllabic one extended with a short vowel (C

1

)V

1

C

2

-V

2

in which -V

2

does not contribute

to the root meaning, e.g.

∗

¯a ‘to be, become’ [333],

∗

key ‘to make’ [1957],

∗

cal ‘to go’

[2781],

∗

man ‘to be’ [4778],

∗

w¯a

.

z ‘to flourish’ [5372],

∗

par-a ‘to spread’ [3949],

∗

i

.

z-i

‘to descend’ [502]; a complex base has a root and a formative suffix, encoding voice,

transitivity or causation, e.g.

∗

a

.

t-a-nku ‘to be subdued, hidden’:

∗

a

.

t-a-nkk ‘to control,

hide’ [63],

∗

key-pi- ‘to cause one to do’; a compound base has more than one root with

the final constituent as a verb, e.g.

∗

akam ‘inside’: Ta. aka-ppa

.

tu ‘to be included’, Te.

aga-pa

.

du ‘to be seen, to f

all in the visual

field’ [7].

Morphologically a verb may be finite or non-finite. A finite verb has the structure

stem + tense-mode + (g)np (gender–number–person) marker, which normally agrees

with the head of the subject noun phrase (NP), Ta. n¯a

ncey-t-¯en ‘I did’, Ko

.

n

.

da v¯anru ki-

t-an ‘he did’. Historically some descendant languages have lost the agreement features,

either partially or fully, like Modern Malay¯a

.

lam, or neutralized all gender–number con-

trasts in the third person,

like Toda and Brahui. A

non-

finite verb has two components,

the verb base + tense/aspect, e.g. Ta

.

cey-tu ‘having done’, Ko

.

n

.

da ki-zi id., perfective

participle or gerund in both the languages; syntactically, it heads a subordinate clause. In

unmarked word order the verb, finite or non-finite, occupies the end position of the clause.

7.3 Intransitive, transitive and causative stems

A simple verb may be inherently intransitive (

∗

¯a- ‘to be’) or transitive (

∗

ciy- ‘to give’)

depending on its meaning and its relationship with the complement phrases in a given

clause. I suggested in section 5.3 (earlier TVB: §2.38, pp. 145–6) that ‘sonorant suffixes

of the R type (l,

.

l, r ,

.

z, w, y) were added to (C)

˘

¯

V- or (C)VC-V-stems to form ex-

tended intransitive/middle-voice stems’. Synchronically, a transitive verb is changed to

intransitive/middle voice in Ku

.

rux and Malto by adding -r, e.g. Ku

.

r. kam- ‘to make’:

kam-r- ‘to be made’, Malt. ey- ‘to bind’: ey-r- ‘to bind oneself’. This seems to be a relic

of a Proto-Dravidian usage, since it is not found in any of the neighbouring Indo-Aryan

and Munda languages. Note that most verbs ending in formative -(V) l/-(V) r in South

Dravidian I and South Dravidian II tend to be intransitive.

Three complementary modes of

forming transitive

–causative stems were quite

an-

cient: (1) by the addition of

∗

-tt to monosyllabic roots that end in an apical stop or nasal

/t

n

.

t

.

n/, and of

∗

-pp to roots ending in final

∗

-i or

∗

-y (the Proto-Dravidian conditions are

not all recoverable). In Central Dravidian both these suffixes got generalized as causative

markers; (2) by the addition of a causative morph -pi- ∼ -wi- ∼ -ppi- to a transitive verb

stem, simple or complex; (3) a complementary type to these is represented by roots of

(C

1

)

¯

VC

2

type, where C

2

is a liquid sonorant, or a disyllabic root of the type (C) VCV- or

(C) VCV-y. A subset of these stems formed transitives by geminating the final stop of

280 The verb

the tense suffixes. In other words, tense and voice were a composite category in this class

of stems. Paradigms of this type survive intact in a subgroup of South Dravidian, namely

Tamil–Malay¯a

.

lam–Ko

.

dagu–Iru

.

la–Toda and Kota (see section 5.4.4); (4) a fourth type,

mainly confined to South Dravidian (SD I and SD II), is the formation of transitive stems

by geminating the final P of the formative syllable in disyllabic or trisyllabic bases. The

final P here is interpreted as part of an erstwhile tense–voice morpheme, which got

incorporated into the base by (3) and lost its tense meaning but retained only the voice

distinction (see section 5.3; earlier Krishnamurti 1997a).

7.3.1 Transitive–causative stems by the addition of

∗

-tt

This pattern is preserved intact in South Dravidian I. Isolated members of the other

subgroups bear evidence to PD

∗

-tt, but they use different additive morphemes.

(1) PD

∗

k¯u

.

tu v.i./tr. ‘to be joined, meet’/v.t.

∗

k¯u

.

t-

.

tu (<

∗

k¯u

.

t-tt-) ‘to unite, put

together’ [1882].

SD I: Ta. Ma. k¯u

.

tu/k¯u

.

t

.

tu, Ko. To. k¯u

.

r-/k¯u

.

t-, Ko

.

d. k¯u

.

d-/k¯u

.

t-, Ka. k¯u

.

du

v.i., k¯u

.

ta ‘joining, connexion’ (derived by adding -a to the transitive base

∗

k¯u

.

t

.

t-), Tu. k¯u

.

duni v.i., k¯u

.

tuni, k¯u

.

n

.

tuni v.t. ‘to mix’, k¯u

.

ta n. ‘mixture’;

SD II: Te. k¯u

.

du v.i., but k¯u

.

d-ali ‘junction’, but k¯u

.

t-ami ‘joining, as-

sembly’.

The other South Dravidian II languages, as well as those of Central Dravidian and North

Dravidian, have only the intransitive form.

(2) PD

∗

uH

.

n/

∗

¯u

.

n ‘to eat, drink’, ¯u

.

t

.

t-(<

∗

uH

.

n-tt-) ‘to give to eat or drink’ [600].

SD I: Ta. u

.

n- v.i./v.t., ¯u

.

t

.

tu- v.t., ¯u

.

n n ‘food’, ¯u

.

t

.

t-am ‘food’ (based on the

caus. stem), Ma. u

.

n

.

nuka/¯u

.

t

.

tuka,Ko

.

d. u

.

n,Ko.u

.

n-/¯u

.

t-, To. u

.

n-, Ko. To. ¯u

.

n

‘food’, Ka. u

.

n-/¯u

.

du v., ¯u

.

ta ‘a meal’, Tu. u

.

npini v., ¯u

.

ta ‘a meal’;

SD II: Te. ¯u

.

tu ‘cattle to drink water completely’, Go. u

.

n

.

d- ‘to drink’, uht-

‘make to drink’, Ko

.

n

.

da u

.

n- ‘to drink’, ¯u

.

t-pis- ‘cause to drink’, Kui u

.

nba-/

¯u

.

tpa-, Kuvi un- ∼ unn- ∼ ¯und-/¯u

.

t-, Pe. u

.

n-/¯u

.

tpa-, Man

.

da u

.

nba-/¯u

.

rpa-;

CD: Kol. Nk. un-/¯ur-t-, Pa. un-/un

.

t-ip-;

ND: Ku

.

r. ¯on- ‘to drink, eat’, ¯on-d-n¯a/on-ta’ ¯an¯a ‘to give a meal’; ¯onk¯a

‘thirst’; Malt. ¯on- ‘to drink, to be coloured’, on-d- ‘to drink, to dye’.

The causative suffix -tt- is retained in South Dravidian I and South Dravidian II with

the exception of Kanna

.

da and Tu

.

lu in South Dravidian I and Telugu and Gondi in South

Dravidian II. Traces of a dental suffix are found in Gondi, Parji and Ku

.

rux–Malto,

justifying its reconstruction for Proto-Dravidian. In Ku

.

rux, a distinction is made between

a transitive with one Agent and a causative with two Agents, e.g. co’on¯a ‘to rise’: c¯o-d-n¯a/

c¯o-da’ ¯an¯a ‘to raise’: c¯o-d-ta’ ¯an¯a ‘to order one to raise’ (Grignard 1924a: 96–7). It

appears the same marker is used both as a transitive and as a causative. It occurs twice in