Jones M., Fleming S.A. Organic Chemistry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1.6 Bond Strength 39

energies. These numbers do not have to be known precisely, but it is important to

have a rough idea of the bond strengths of common covalent bonds.

Table 1.9 gives averages over a range of compounds. A few compounds may lie

outside these values. In later chapters more precise specific values will appear.

Let’s consider the simplest molecule, which is H

2

with only one electron and

a positive charge. Even this molecule is bound quite strongly.

10

The small amount

of information already in hand—a molecular orbital picture of H

2

and the bond

strength of the bond (104 kcal/mol)—enables us to

construct a picture of this exotic molecule and to estimate

its bond strength. We can imagine making by allow-

ing a hydrogen atom, to combine with H

, a bare pro-

ton. All the work necessary to create an orbital interaction

diagram for this reaction was done in the construction of

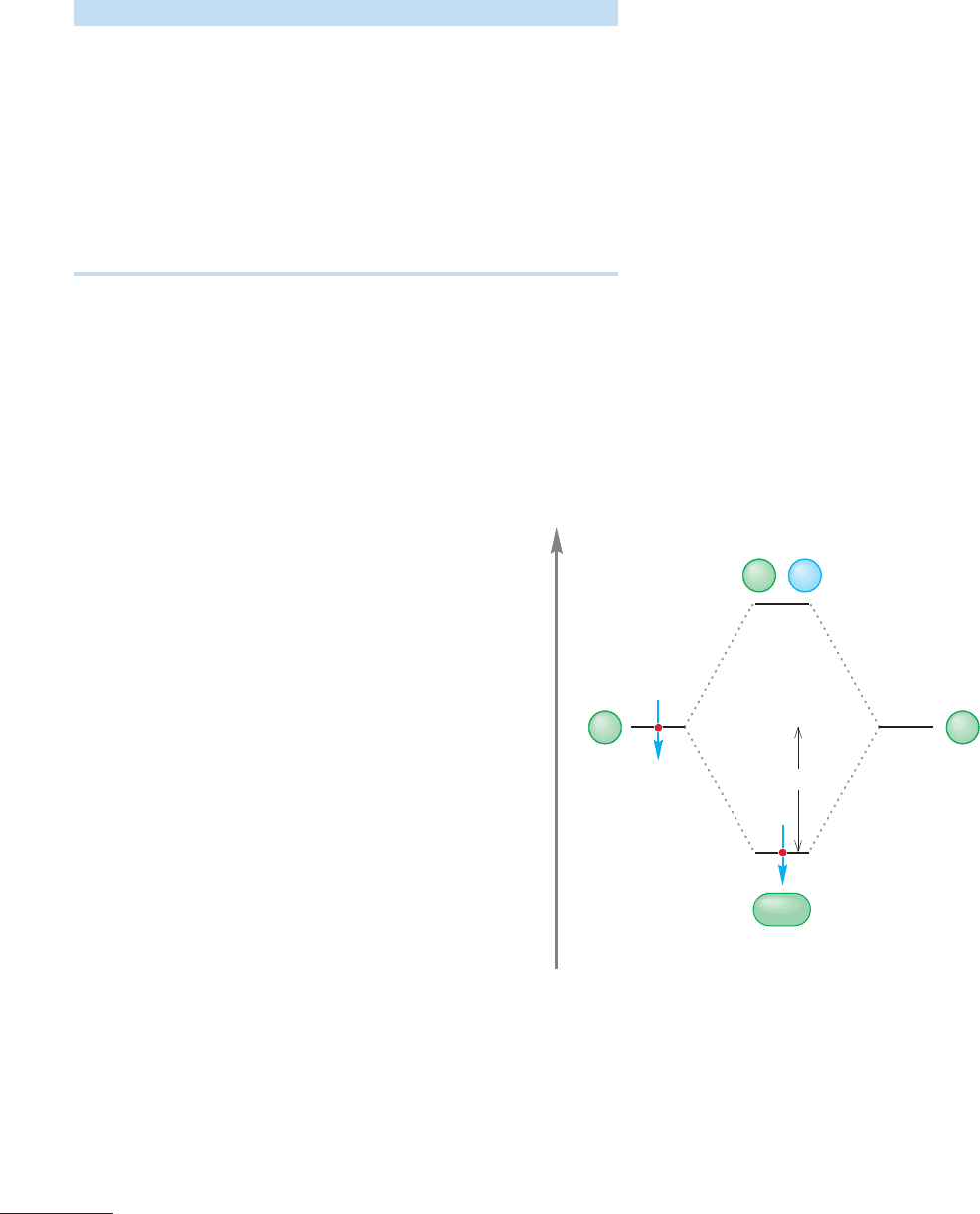

Figure 1.39.We are still looking at the combination of a pair

of hydrogen 1s atomic orbitals, so the building of a diagram

for produces precisely the same orbital diagram,repro-

duced in Figure 1.45. The only difference comes when we

put in the electrons.Instead of having two electrons,as does

H

2

, with one coming from each hydrogen atom, has

only one electron. Naturally, it goes into the lower-energy,

bonding molecular orbital, The electron spin is shown

down, but it could equally well be shown up. There is no

difference in energy between the two spins and we have no

way of knowing which way a single spin is oriented.

What might we guess about the bond energy of this

molecule If two electrons in result in a bond ener-

gy of 104 kcal/mol, it seems reasonable to guess first that

stabilization of a single electron would be worth half the amount, or about

52 kcal/mol.That is, when an atom and an H

ion combine to form the species

we are estimating that 52 kcal/mol of heat is given off. And we are amazing-

ly close to being correct! The molecule is bound by 64 kcal/mol (Fig. 1.45),

which means that the system is 64 kcal/mol more stable than the system of a

separated and H

.H

.

H

2

+

H

2

+

H

2

+

,

H

.

£

B

H

2

+

?

£

B

.

H

2

+

H

2

+

H

.

,

H

2

+

H

O

H

H

2

+

,

10

Here is the answer to Problem 1.22. The simplest molecule is hydrogen (H

2

) minus one electron. Another

electron cannot be removed to give something even simpler because is not a molecule—there are no

electrons to bind the two nuclei.

H

2

2+

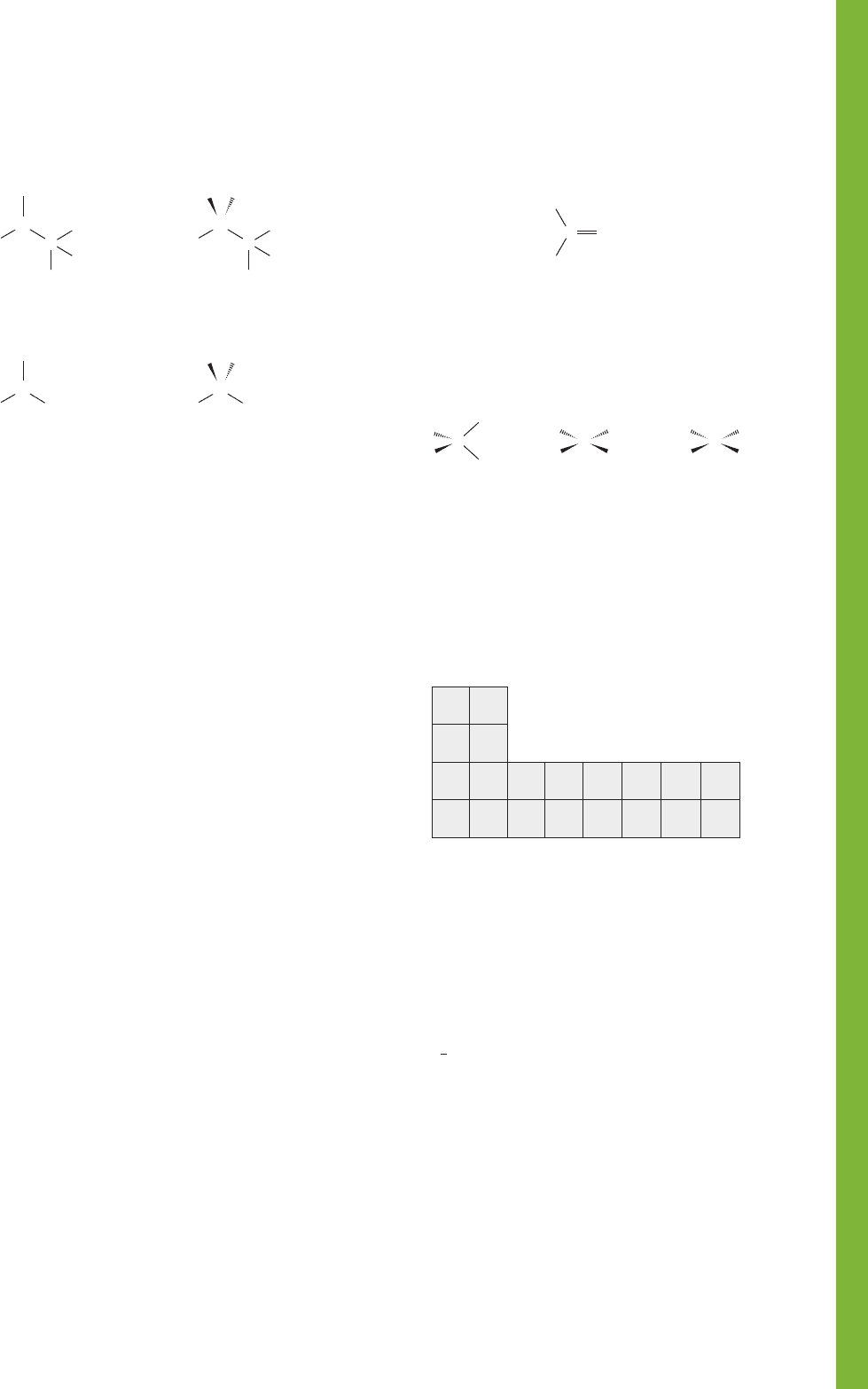

TABLE 1.9 Some Average Bond Dissociation Energies

Bond BDE (kcal/mol) Bond BDE (kcal/mol)

96–105 55–57

93–107 175

110–119 143

82–87 173–181

83–90 230

85–96 204

69–75 71

105–115 88

83–85 103

72–74 136H

O

FC

O

Br

H

O

ClC

O

Cl

H

O

BrC

O

F

H

O

IC

O

N

'

C

q

NC

O

O

'

C

q

CC

O

C

C

P

OS

O

H

'

C

P

NO

O

H

'

C

P

CN

O

H

C

O

IC

O

H

64 kcal/mol

Energy

Φ

A

Φ

B

ψ(H

a

, 1s

1

)

ψ(H

b

, 1s

0

)

+

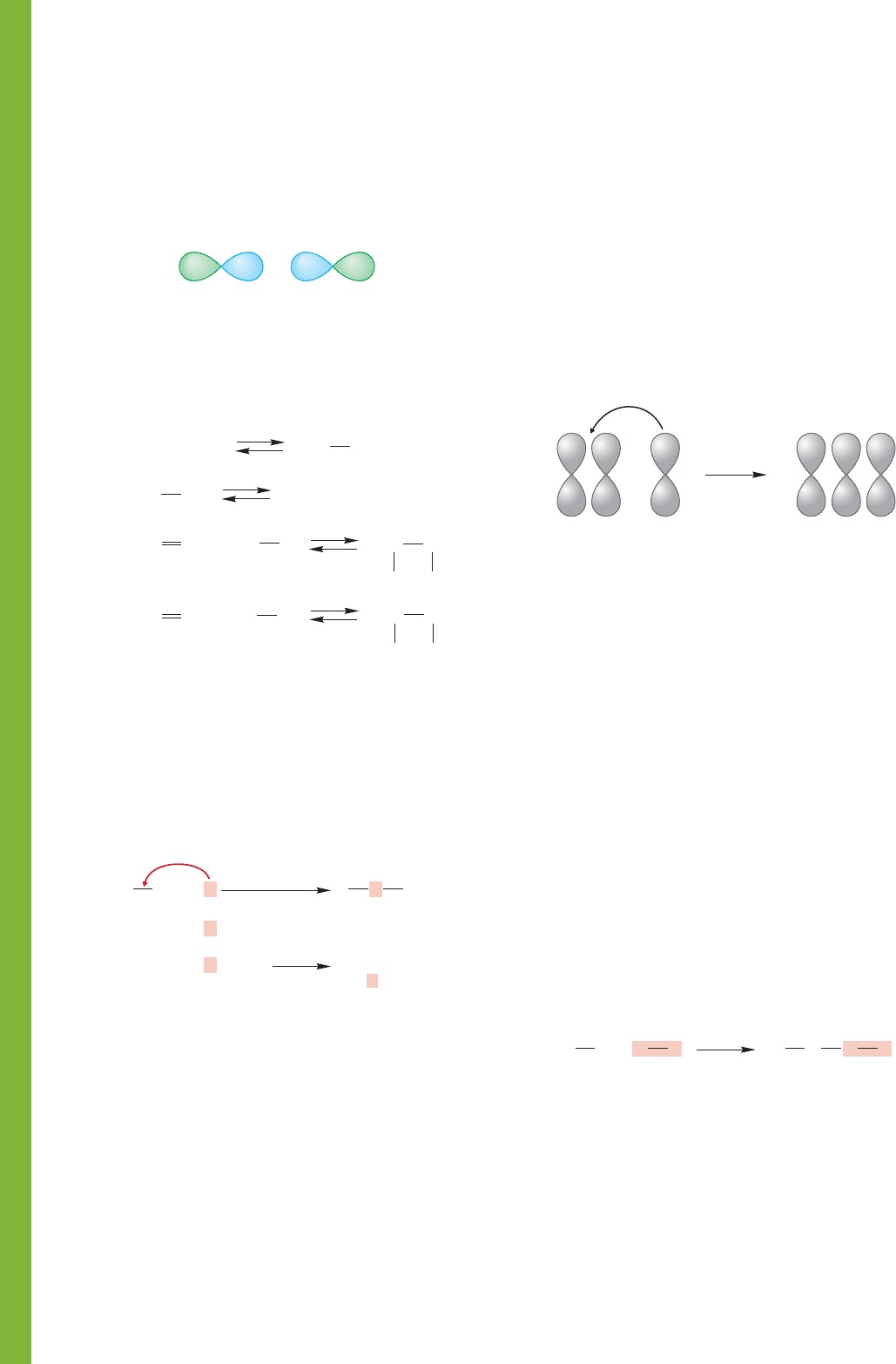

FIGURE 1.45 An orbital interaction

diagram for .

H

2

+

Energy

Φ

A

Φ

B

(He

b

1s

2

)(He

a

1s

2

)

40 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

PROBLEM 1.27 Although our guess 52 kcal/mol is quite close to the actual value,

it is a bit low. In other words, the molecule is more stable (lower in energy)

than we thought. Why is our estimate of bond strength a little low? To ask the

same question another way, why might the stabilization of two electrons in an

orbital be less than twice the stabilization of one electron in the orbital? Hint:

Consider electron–electron repulsion.

It may seem somewhat counterintuitive that a low-energy (strong) bond is asso-

ciated with a large number for the BDE.The lower the energy of a bond, the high-

er the number representing bond strength! The low-energy, strong bond in H

2

has

a BDE of 104 kcal/mol, for example, whereas the higher-energy, weaker bond in

has a BDE of only 64 kcal/mol. A strong bond means a low-energy, stable

species. The diagram in Figure 1.42 should help keep this point straight. A strong

bond means a more stable bond and it means a lower position on an energy diagram.

Remember the sign convention: The

minus sign tells us that this reaction is exothermic as read from left to right. An

exothermic reaction will have products that are more stable than the starting ma-

terials. The products will be lower than the reactants on the energy diagram.

The antibonding molecular orbital has been empty in all of the examples

we have considered. Why the emphasis on What is an empty orbital, anyway?

The easiest,nonmathematical way to think of in H

2

is as the place the next elec-

tron would go. If the bonding molecular orbital is filled, as it is in H

2

, for exam-

ple (Fig. 1.42), another electron cannot occupy and must go instead into the

antibonding orbital, This would create

Dihelium, He

2

, a strictly hypothetical species, is an example of a molecule in

which electrons must occupy antibonding orbitals. Each He, like each H in H

2

,

brings only a 1s orbital to the mixing. Just as in the molecules H

2

and the

molecular orbitals for He

2

are created by the combination of two 1s atomic orbitals

(Fig. 1.46). Each helium atom brings two electrons to the molecule, though, so the

electronic occupancy of the orbitals will be different from that for H

2

or The

bonding orbital can hold only two electrons (Pauli principle, p. 8) so the next

two must occupy The two electrons in this antibonding orbital are destabiliz-

ing to the molecule, just as the two electrons in are stabilizing. As a result, there

£

B

£

A

.

1£

B

2

H

2

+

.

H

2

+

,

H

2

-

1H

2

+ e

-

U

H

2

-

2.£

A

.

£

B

£

B

£

A

£

A

?

1£

A

2

¢H ° =-104 kcal>mol.2 H

.

U

H

O

H,

H

2

+

H

2

+

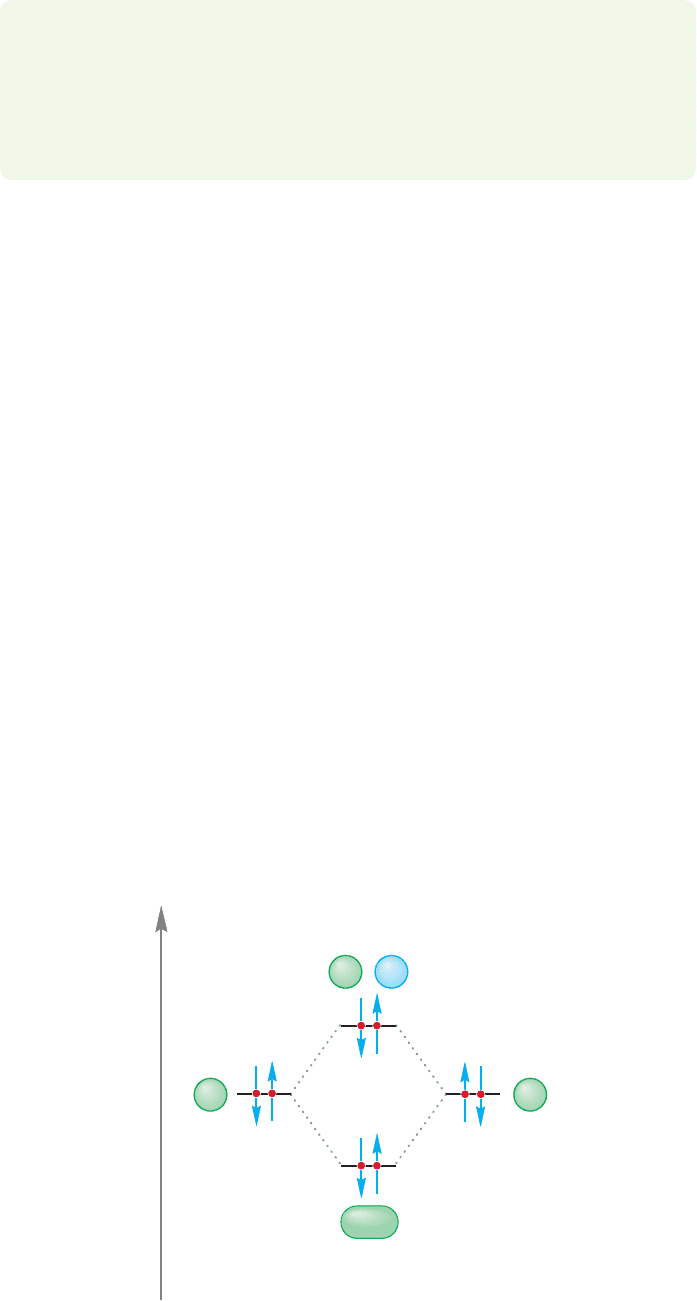

FIGURE 1.46 An orbital interaction

diagram for He

2

.There is no net

bonding because the stabilization

owing to the pair of electrons in the

bonding molecular orbital is offset by

the destabilization from the two

electrons in the antibonding orbital.

1.7 An Introduction to Reactivity: Acids and Bases 41

is no net bonding in the hypothetical molecule He

2

. The stabilization afforded by

the two electrons in the bonding molecular orbital is cancelled by the destabiliza-

tion resulting from the two electrons in the antibonding molecular orbital. Molecular

helium He

2

is, in fact, unknown.

Summary

The energy of an electron in a bonding molecular orbital generated through

mixing of two orbitals depends primarily on the extent of mixing between the two

orbitals that combine to produce it. Extensive interaction leads to a low-energy

bonding molecular orbital (and a high-energy antibonding molecular orbital).

Thus, one or two electrons in such an orbital will be well stabilized. The bond

joining the two atoms is strong. Orbitals that are orthogonal do not mix.

PROBLEM 1.28 Draw the orbital interaction diagram for

WORKED PROBLEM 1.29 Estimate the bond strength for

Show how you arrived at your estimate.

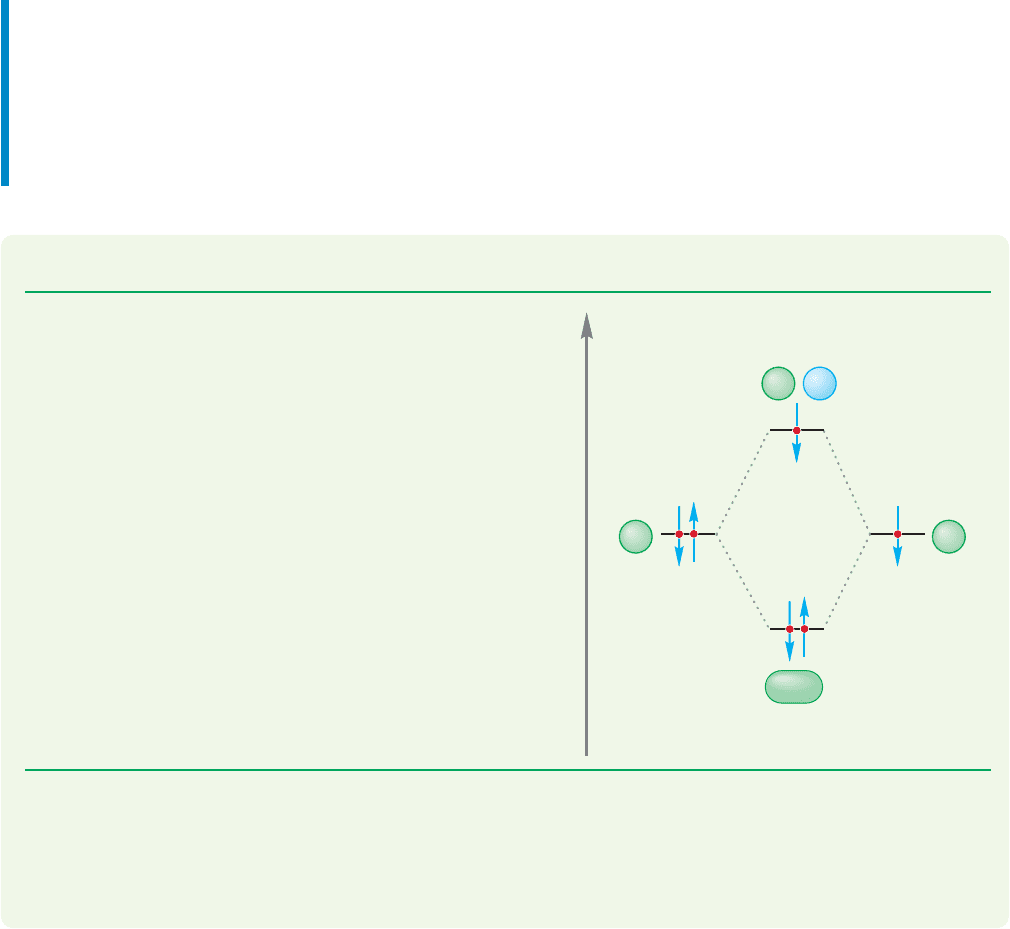

ANSWER The molecular orbital diagram for this molecule can

be easily derived from Figure 1.46 by removing one electron.

The molecule can be constructed from He and He

.This

molecule will have only three electrons. Assuming that an elec-

tron in the antibonding orbital destabilizes the molecule

about as much as one in the bonding orbital stabilizes, there

is one net bonding electron in this molecule (2 bonding elec-

trons – 1 antibonding electron 1 net bonding electron). The

should have a bond strength about the same amount as

another molecule with a single electron in the bonding

molecular orbital. This estimate turns out to be correct. The

bond energy for has been experimentally measured to be

about 60 kcal/mol.

PROBLEM 1.30 Use the answer to Problem 1.27 to work out the answer to a more

subtle question. In He

2

, both the bonding and the antibonding molecular orbitals

are filled with two electrons. Consider electron–electron repulsion to explain why

the stabilization of the two electrons in is less than the destabilization of the

electrons in

1.7 An Introduction to Reactivity: Acids and Bases

Even at this early point we can begin to consider what many see as the real business of

chemistry—reactivity. The orbital interaction diagrams we have just learned to draw

lead us to powerful unifying generalizations. Remember that we can fit no more than

two electrons into any atomic or molecular orbital (p. 8). There are two ways to pro-

vide the electrons that fill the bonding molecular orbital so as to stabilize two electrons.

£

A

.

£

B

He

2

+

H

2

+

,

He

2

+

£

B

£

A

He

2

+

He

2

+

.

He

2

+

.

Energy

ψ(He

a

, 1s

2

)

Φ

B

Φ

A

ψ(He

b

, 1s)

+

42 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

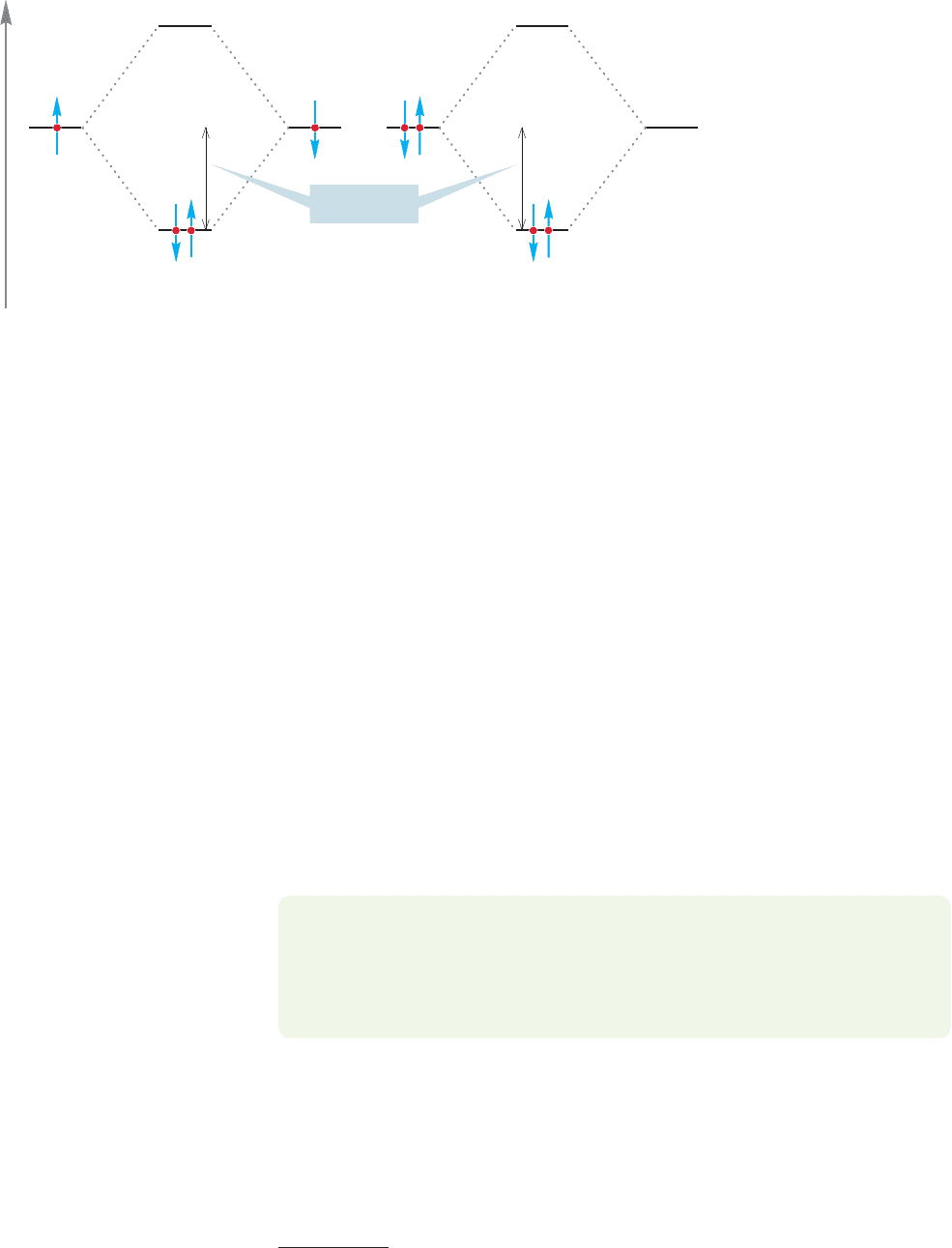

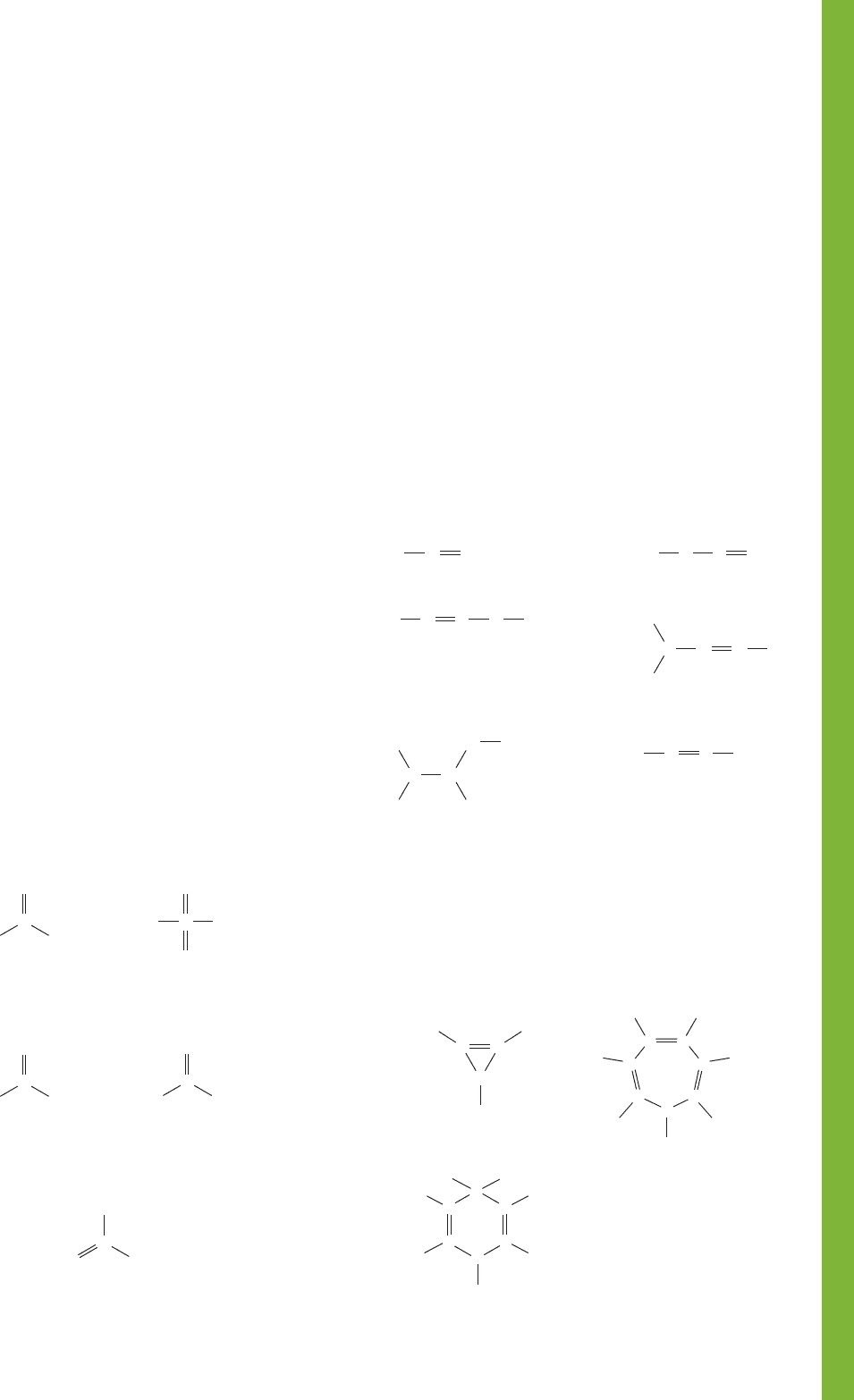

Figure 1.47a shows a pair of

electrons, each in a singly

occupied orbital, combining

to produce a bond in which

the two electrons are stabi-

lized (both electrons move

down to a lower energy

value). Alternatively, we

could imagine the situation

outlined in Figure 1.47b, in

which a filled orbital mixes

with an empty orbital to

produce a similar stabiliza-

tion. An atom or molecule that is a two-electron donor is called a Lewis base.An

atom or molecule that is a two-electron acceptor is called a Lewis acid.These labels

were introduced by G. N. Lewis (p. 14).

Both these bond-forming scenarios are common,but the scenario in Figure 1.47b

is especially important. We have already seen an example of the process shown in

Figure 1.47a, when we considered a pair of hydrogen atoms combining to form H

2

(Fig. 1.42). We have not yet seen any real examples of the Lewis acid–Lewis base

situation, but we will encounter hundreds as we work through this book.

You are probably familiar with Brønsted acids and bases (proton donors and

acceptors, respectively), but the situation described by Figure 1.47b is much more

general. It would seem that a stabilizing (energy-lowering) bond-forming interac-

tion can take place whenever a filled orbital overlaps with an empty orbital. We will

give this important idea the careful treatment it deserves in Chapters 3 and 7, but

it is worth thinking about it a bit right now.

Organic chemists use the terms electrophile for Lewis acid and nucleophile for

Lewis base. The combination of a Lewis base and a Lewis acid (or nucleophile

electrophile), conceptualized in the orbital interaction diagram of Figure 1.47b, leads

to formation of a covalent bond.The concepts that “Lewis bases react with Lewis acids”

and “the interaction of a filled orbital with an empty orbital leads to bond formation

and stabilization of two electrons”run throughout organic (and other) chemistry.These

two concepts allow us to generalize and not to be swamped by all the prolific detail

soon to come. Nucleophile electrophile is the unifying theme of organic chemistry.

FIGURE 1.47 Two interactions that

lead to stabilization of a pair of

electrons.

11

By Walter Kauzmann (1916–2009) in an early book,Quantum Chemistry, Academic Press, New York, 1957.

Energy

Stabilization

(a) (b)

PROBLEM 1.31 Identify the Lewis base (nucleophile) and Lewis acid (electrophile)

in each of these reactions. Write the molecule formed in each case.

(a) (b)

(c) (d)

H

3

C

+

:

NH

3

U

?H

3

C

+

-

:

CH

3

U

?

H

+

-

:

O

.

.

.

.

H

U

?H

+

H

:

-

U

?

1.8 Special Topic: Quantum Mechanics and Babies

We might imagine that molecular orbitals and quantum mechanics,so critical in the

microscopic world, would have little real influence on our day-to-day lives because

we really do live in a world of baseballs, not electrons. Or so it would seem. Yet it

has been argued

11

that “a new-born baby becomes conscious of . . . the consequences

1.9 Summary 43

[of the Pauli principle] long before he finds it necessary to take account of the con-

sequences of Newton’s laws of motion.” How so? Ernest Rutherford (p. 2) told us

long ago that an atom is essentially empty space because the nucleus is very small

compared to the size of a typical atom, and electrons are even tinier than the nucle-

us. Why is it then, that when “solid” objects come together they do not smoothly

pass through one another, as they sometimes do in 3

A.M. science fiction movies?

The answer is that the apparent solidity of matter is the result of Pauli forces.

When your hand encounters the table top, the electrons in the atoms of your hand

and the electrons in the atoms of the table top have the same spins and nearly the

same energies. The Pauli principle ensures that these electrons cannot occupy the

same regions of space, that the table top feels solid to your touch, even though

Rutherford showed us that it is not. Were it not for the Pauli principle our appre-

hension of the world would be vastly different.

Atomic orbitals (mathematically described by wave functions)

are defined by four quantum numbers, n, l, m

l

, and s. Electrons

may have only certain energies determined by these quantum

numbers. Orbitals have different, well-defined shapes: s orbitals

are spherically symmetric, p orbitals are roughly dumbbell

shaped, d and f orbitals are more complicated. An orbital may

contain a maximum of two electrons.

Some molecules cannot be well described by a single Lewis

structure but are better represented by two or more different

electronic descriptions. This phenomenon is called resonance.Be

sure you are clear on the difference between an equilibrium

between two different molecules and the description of a single

molecule using a number of different resonance forms.

When two orbitals overlap, two new orbitals are formed:

one lower in energy than the starting orbitals, the other higher

in energy than the starting orbitals. Electrons placed in the new,

lower-energy orbital are stabilized because their energy is low-

ered. The overlap of atomic orbitals to form molecular orbitals

and the attendant stabilization of electrons as they move from

the atomic orbitals to the lower-energy molecular orbitals are

the basis of covalent bonding.

This orbital-forming process can be generalized: when you

mix n orbitals into the calculation, the mathematical solution

will produce n new orbitals.

anion (p. 4)

antibonding molecular orbital (p. 32)

arrow formalism, curved arrow formalism,

or electron pushing (p. 23)

atom (p. 2)

atomic orbital (p. 3)

aufbau principle (p. 8)

bond dissociation energy (BDE) (p. 37)

bonding molecular orbital (p. 32)

cation (p. 4)

covalent bond (p. 6)

delocalization (p. 27)

dipole moment (p. 14)

electron (p. 2)

electron affinity (p. 4)

electronegativity (p. 15)

electrophile (p. 42)

endothermic reaction (p. 36)

enthalpy change (¢H°) (p. 36)

exothermic reaction (p. 36)

formal charge (p. 20)

functional group (p. 22)

Heisenberg uncertainty principle (p. 2)

heterolytic bond cleavage (p. 37)

homolytic bond cleavage (p. 37)

Hund’s rule (p. 9)

ion (p. 4)

ionic bond (p. 5)

ionization potential (p. 4)

Lewis acid (p. 42)

Lewis base (p. 42)

Lewis structure (p. 14)

lone-pair electrons (p. 14)

molecular orbital (p. 3)

node (p. 6)

nonbonding electrons (p. 14)

nonbonding orbital (p. 32)

nucleophile (p. 42)

nucleus (p. 2)

octet rule (p. 4)

orbital (p. 3)

orbital interaction diagram (p. 33)

orthogonal orbitals (p. 34)

paired spin (p. 8)

parallel spin (p. 10)

Pauli principle (p. 8)

polar covalent bond (p. 14)

quantum numbers (p. 6)

resonance arrow (p. 23)

resonance forms (p. 22)

tautomers (p. 29)

unpaired spin (p. 8)

valence electrons (p. 16)

wave function (ψ) (p. 6)

weighting factor (p. 26)

Key Terms

1.9 Summary

New Concepts

44 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

There are no reactions to speak of yet, but we have developed a

number of tools in this first chapter.

Lewis structures are drawn by representing each valence

electron by a dot. These dots are transformed into vertical arrows

if it is necessary to show electron spin. Exceptions are the ls

electrons, which are held too tightly to be importantly involved

in bonding except in hydrogen. These electrons are not shown in

Lewis structures except in H and He. Somewhat more abstract

representations of molecules are made by showing electron pairs

in bonding orbitals as lines—the familiar bonds between atoms.

The double-headed resonance arrow is introduced to cope

with those molecules that cannot be adequately represented by a

single Lewis structure. Different electronic representations, called

resonance forms, are written for the molecule. The molecule is

better represented by a combination of all the resonance forms.

Be very careful to distinguish the resonance phenomenon from

chemical equilibrium. Resonance forms give multiple descrip-

tions of a single species. Equilibrium describes two (or more)

different molecules.

The curved arrow formalism is introduced to show the flow

of electrons. This critically important device is used both in

drawing resonance forms and in sketching electron flow in reac-

tions throughout this book.

The formation of a bonding molecular orbital (lower in

energy) and an antibonding molecular orbital (higher in energy)

from the overlap of two atomic orbitals can be shown in an

orbital interaction diagram (Fig. 1.48). Electrons are represented

by vertical arrows which also show electron spin ( or ).

Remember that only two electrons can be stabilized in the

bonding orbital and that two electrons in the same orbital must

have opposite spins.

[\

Reactions, Mechanisms, and Tools

New molecular orbital 2

antibonding

New molecular orbital 1

bonding

Atomic orbital 1

Atomic orbital 2

Energy

FIGURE 1.48 The overlap of two atomic orbitals produces two

new molecular orbitals.

Here, and in similar sections throughout the book, we will take

stock of some typical errors made by those who attempt to

come to grips with organic chemistry.

Electrons are not baseballs. Nothing is harder for most stu-

dents to grasp than the consequences of this observation.

Electrons behave in ways that the moving objects in our ordi-

nary lives do not. No one who has ever kicked a soccer ball or

caught a fly ball can doubt that on a practical level it is possible

to determine both the position and speed of such an object at

the same time. However, Heisenberg demonstrated that this is

not true for an electron. We cannot know both the position and

speed of an electron at the same time.

Baseballs move at a variety of speeds (energies), and a base-

ball’s energy depends only on how hard we throw it. Electrons

are restricted to certain energies (orbitals) determined by the val-

ues of quantum numbers. Electrons behave in other strange and

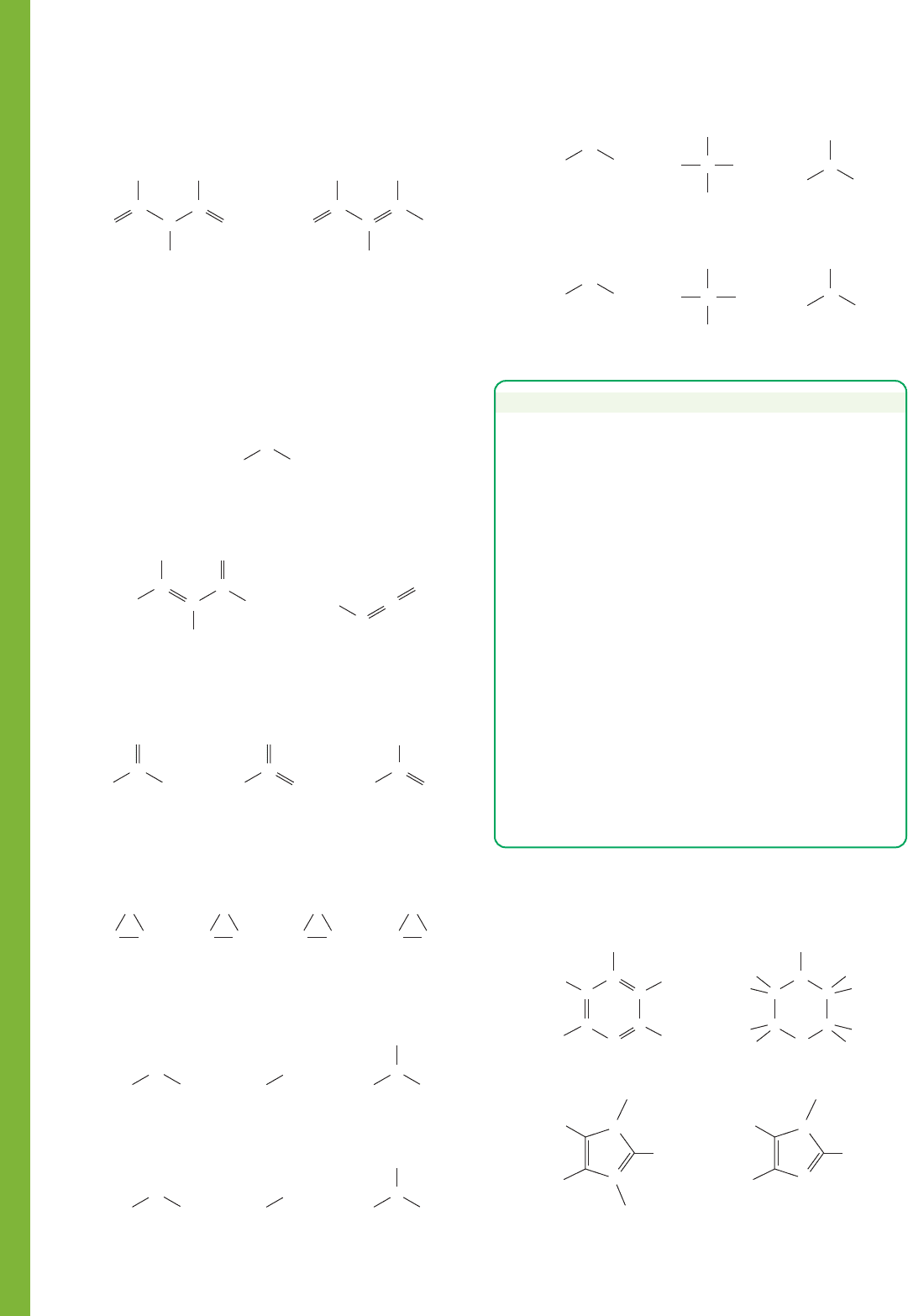

counterintuitive ways. For example, we have seen that a node is a

region of space of zero electron density. Yet, an electron occupies

an entire 2p orbital in which the two halves are separated by a

nodal plane. A favorite question, How does the electron move

from one lobe of the orbital to the other? simply has no mean-

ing. The electron is not restricted to one lobe or the other but

occupies the whole orbital (Fig. 1.49). Mathematics makes these

properties seem inevitable; intuition, derived from our experi-

ence in the macroscopic world, makes them very strange.

It is easy to confuse resonance with equilibrium. On a mun-

dane, but nonetheless important level, this confusion appears as a

misuse of the arrow convention. Two arrows separate two entirely

different molecules (A and B), each of which might be described

by several resonance forms.The amount of A and B present at

equilibrium depends on the equilibrium constant. The double-

headed resonance arrow separates two different electronic

descriptions (C and D) of the same species, E (Fig. 1.29).

Constructing molecular orbitals through combinations of

atomic orbitals (or other molecular orbitals) can be daunting, at

least in the beginning. Remember these hints:

1. The number of orbitals produced at the end must equal the

number at the beginning. If you start with n orbitals, you

must produce n new orbitals. Here is a way to check your

work as it proceeds.

Common Errors

.

FIGURE 1.49 An electron occupies an entire 2p (or other)

orbital—it is not restricted to only one lobe.

1.10 Additional Problems 45

2. Keep the process as simple as you can. Use what you know

already, and combine orbitals in as symmetrical a fashion as

you can.

3. The closer in energy two orbitals are, the more strongly

they interact. At this level of theory, you need only interact

the pairs of orbitals closest in energy to each other.

4. When orbitals interact in a bonding way (same sign of the

wave function), the energy of the resulting orbital is lowered;

when they interact in an antibonding way (different signs of

the wave function), the energy of the resulting orbital is raised.

5. To order the product orbitals in energy, count the nodes. For

a given molecule, the more nodes in an orbital, the higher it

is in energy.

These methods will become much easier than they seem at

first, and they will provide a remarkable number of insights into

structure and reactivity not easily available in other ways.

The sign convention for exothermic and endothermic

reactions seems to be a perennial problem. In an exothermic

reaction, the products are more stable than the starting materials.

Heat is given off in the reaction and is given a minus sign.

Thus, for the reaction An

endothermic reaction is just the opposite. Energy must be

applied to form the less stable products from the more stable

starting material. The sign convention gives a plus sign.

Thus, ¢H ° =+x kcal>mol.A + B

U

C,

¢H °

¢H ° =-x kcal>mol.A + B

U

C,

¢H °

PROBLEM 1.32 Draw Lewis dot structures for the following

compounds:

(a) CH

3

NO

2

(nitromethane, used for fuel in stock car racing)

(b) (vinyl chloride used to make polyvinyl

chloride)

(c) CH

3

CO

2

H (acetic acid, the acid in vinegar)

(d) HOSO

2

OH (sulfuric acid, H

2

SO

4

, the world’s most widely

used industrial chemical)

See the inside front cover for structures, if you don’t know them.

PROBLEM 1.33 Draw two resonance structures for each of the

compounds in the previous problem. Show the arrow pushing

for interconverting the resonance forms for each compound.

PROBLEM 1.34 Use the arrow formalism to write structures

for the resonance forms contributing to the structures of the

following ions:

..

..

Carbonate ion

C

OO

O

(a)

..

..

..

..

..

..

–

–

Sulfate ion

(b)

O

..

..

..

O

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

S

O

O

––

Nitrate ion

(c)

+

..

..

N

OO

O

..

..

..

..

..

..

––

Guanidinium ion

(d)

....

+

C

NH

2

H

2

N

NH

2

A vinyl ammonium ion

(e)

+

C

N(CH

3

)

3

H

2

C

H

CH

2

P

CHCl

PROBLEM 1.35 Use the arrow formalism to write resonance

forms contributing to the structures for the following molecules:

1.10 Additional Problems

..

..

..

(e)

(f)

..

–

..

..

..

NO

+

–

CCH

3

CH

3

+

NC

CH

3

NH

3

C

H

3

C

(d)

(c)

–

.. ..

..

CH

3

C

+

NNCH

3

+

–

NCH

3

C

H

3

C

H

3

C

C

..

..

+

–

NH

2

C

(a) (b)

N

..

..

..

..

NH

3

C

N

+

–

N

..

..

..

PROBLEM 1.36 Draw three resonance structures for each of

the following:

(a)

CH

2

NO

2

(b) CH

3

CO

2

CH

3

(c) (d) HOSO

2

O

PROBLEM 1.37 Draw resonance forms for the following cyclic

molecules:

H

H

H

H

H

H

HH

H

H

H

H

(a) (b)

(c)

..

CC

C

H

HH

–

H

H

C

C

CC

C

C

+

C

C

CC

C

C

C

+

-

CH

2

CO

2

-

46 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

PROBLEM 1.38 Draw resonance forms for the following

acyclic molecules:

PROBLEM 1.39 Ozone (O

3

) resembles the molecules in

Problem 1.35. These days it has a rather bad press, as it is

present in too small an amount in the stratosphere and too

great an amount in cities. Write a Lewis “dot” structure for

ozone and sketch out contributing resonance forms. Write one

neutral resonance form. Be careful with this last part; the

answer is tricky.

PROBLEM 1.40 Draw two resonance structures for each of the

compounds shown below.

PROBLEM 1.41 Which “resonance structure” does not contribute

to the molecule CH

3

NOCH

2

. Why doesn’t it contribute?

PROBLEM 1.42 Add charges to the following molecules where

necessary:

PROBLEM 1.43 Add charges to the following molecules where

necessary:

(a) (b) (c)

(d) (e) (f)

H

3

CH

O

H

..

..

H

3

C

O

H

3

C

H

O

..

..

..

..

H

3

CH

S

H

..

..

H

3

C H

3

C

H

S

..

..

..

..

S

(a) (b) (c) (d)

H

2

CCH

2

O

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

H

2

CCH

2

N

H

2

CCH

2

Br

H

2

CCH

2

S

(a)

H

3

CH

3

CH

3

CCH

2

N

O

–

–

++

(b)

CH

2

N

..

..

..

O

..

..

(c)

CH

2

N

O

..

..

..

(a)

H

3

CC

C

HO

C

H

CH

3

(b)

H

3

C

O

N

C

O

O

O

(a)

H

2

CC

C

HH

C

H

–

CH

2

(b)

H

2

C

C

C

HH

C

H

CH

2

..

–

..

PROBLEM SOLVING

What to do with a “strange”atom like S or P in Problem

1.43? Organic chemistry is largely, but not entirely,

confined to the second row of the periodic table, so what

do you do when you encounter some atom that is not in

the second row? First, don’t panic—if you know the

second row of the periodic table, you can deal with most

of the “strange” atoms you will see. But you do have to

know a few more things. First, P, Si, and S sit right below

N, C, and O. Second, the halogens form a series: F, Cl,

Br, I. If you know the electron counts for the second-row

elements, you don’t have to go through the more

elaborate counting necessary to deal with elements in

subsequent rows. If neutral trivalent N has a pair of

nonbonding electrons, so does P. If neutral divalent O

has two pairs of electrons, so does S. Therefore, HOH

and HSH are related. If tetravalent N is positively

charged, as in H

4

N

, so is tetravalent P as in H

4

P

.

We’ll deal later with atoms further down in the

periodic table.

(g) (h) (i)

(j) (k) (l)

H

3

CH

H

..

..

H

3

C

H

N

H

3

C

H

H

..

..

H

3

CH

P

N

..

P

..

H

3

C

H

H

NH

H

3

C

H

H

PH

PROBLEM 1.44 Determine the formal charge, if there is one,

for each of the nitrogens in the following molecules:

H

H

H

HH

(a)

N

C

CC

C

N

..

H

H

H

(b)

H

H

H

H

H

H

N

C

CC

C

N

..

..

..

(d)

H

H

H

(c)

N

..

H

N

H

H

N

H

N

..

..

..

..

H

N

1.10 Additional Problems 47

PROBLEM 1.53 Would you expect formaldehyde, shown below,

to have a greater dipole moment than carbon monoxide (see

Problem 1.52)? Why or why not?

PROBLEM 1.54 Consider three possible structures for methyl-

ene fluoride (CH

2

F

2

), one tetrahedral (structure A), the others

flat (structures B and C). Does the observation of a dipole

moment in CH

2

F

2

allow you to decide between structures A

and B? What about structures A and C?

PROBLEM 1.55 Draw the electron pushing for the homolytic

cleavage of Br

2

. Draw the electron pushing for heterolytic cleav-

age of Br

2

.

PROBLEM 1.56 While wandering in an alternative universe

you find yourself in a chemistry class and, quite naturally, you

glance at the periodic table on the wall. It looks (in part) like

this:

Deduce the allowed values for the four quantum numbers in

the alternative universe.

PROBLEM 1.57 In a different alternative universe, the follow-

ing restrictions on quantum numbers apply:

n 1, 2, 3, . . .

l n 1, n 2, n 3,...,0

m

l

l 1, l,...,0,...,l 1

Call the elements in this universe 1, 2, 3, . . . and assume that

Hund’s rule and the Pauli principle still apply.

(a) For n 1, 2, and 3 show what orbital subshells are available

and label them as s, p, d, and so on.

(b) How many electrons can be accommodated in the first three

shells (n 1, 2, and 3) in this universe?

(c) Provide electronic descriptions for elements 1 through 14 in

this universe. (In our universe Li would be written 1s

2

2s.)

(d) Construct a periodic table for elements 1 through 23 in this

universe.

s = 앐

1

2

1

H

2

He

3

Li

4

Be

5

B

6

C

13

Al

14

Si

7

N

8

O

15

P

16

S

9

F

10

Ne

17

Cl

18

Ar

11

Na

12

Mg

19

K

20

Ca

C

A

F

F

H

H

B

C

H

F

F

H

C

C

H

H

F

F

C

H

H

..

..

O

PROBLEM 1.45 Determine the formal charges, if any, for the

molecules shown below.

PROBLEM 1.46 Write Lewis dot structures for the neutral

diatomic molecules F

2

and N

2

. In F

2

, there is a single bond

between the two atoms, but in N

2

there is a triple bond between

the two atoms.

PROBLEM 1.47 Atomic carbon can exist in several electronic

states, one of which is (of course) lowest in energy and is called

the “ground state.” Write the electronic description for the

ground state and at least two higher energy, “excited states.”

PROBLEM 1.48 Write the electronic configurations for the fol-

lowing ions:

(a) Na

(b) F

(c) Ca

2

PROBLEM 1.49 Write the electronic configurations for the atoms

in the fourth row of the periodic table,

19

K through

36

Kr. Hint:

The energy of the 3d orbitals falls between that of the 4s and 4p

orbitals. Don’t worry about the m

l

designations of the 3d orbitals.

PROBLEM 1.50 Write electronic configurations for

14

Si,

15

P,

and

16

S. Indicate the spins of the electrons in the 3p orbitals

with a small up or down arrow.

PROBLEM 1.51 There is an instrument, called an electron spin

resonance (ESR) spectrometer, that can detect “unpaired spin.”

In which of the following species would the ESR machine find

unpaired spin? Explain.

(a) O (b) O

(c) O

2

(d) Ne

(e) F

PROBLEM 1.52 For the Lewis structure of carbon monoxide

shown below, first verify that both the carbon and the oxygen

atoms are neutral.

Second, indicate the direction of the dipole moment in this

Lewis structure:

As you have just shown, based on this Lewis structure, carbon

monoxide should have a substantial dipole moment. In fact, the

experimentally determined dipole moment is very small, 0.11 D.

Draw a second resonance structure for carbon monoxide, verify the

presence of any charges, and indicate the direction of any dipole in

this second resonance form. Finally, rationalize the observation of

only a very small dipole moment in carbon monoxide.

:

C

P

O

.

.

:

(a)

C

H

H

H

Al

H

H

(b)

C

H

H

H

Al

HH

H

(c)

H

H

Al

H

(d)

H

H

Al

HH

48 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

PROBLEM 1.58 In Problem 1.25, you looked at two possible

interactions of a pair of 2p orbitals: side-by-side and

perpendicular, or end-on. Now let a pair of 2p orbitals

interact end to end, and draw the two new molecular orbitals

produced.

PROBLEM 1.59 Indicate whether the following reactions are

exothermic or endothermic. Estimate by how much. Use

Table 1.9 (p. 39) and 66 kcal/mol for the “double” part of

.

PROBLEM 1.60 Let’s extend our discussion of a

little bit to make the orbitals for the molecule linear

HHH. Use the molecular orbitals for H

2

and the 1s atomic

orbital of H. Place the new H in between the two hydrogen

atoms of . Watch out for net-zero (orthogonal)

interactions!

(a) How many orbitals will there be in linear HHH?

(b) Use the molecular orbitals of H

2

and the 1s orbital of

hydrogen to produce the molecular orbitals of linear HHH.

Sketch the new orbitals.

(c) Order the new orbitals in energy (count the nodes).

HH

H

2

, ⌽

B

, ⌽

A

HHH

H, 1s

H

H Atomic

orbital

+

–

Molecular

orbitals

Molecular orbitals

for HHH

H

2

+

–

H

O

H

H

O

H

HH

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

H

3

CH

3

C

H

3

C

H

H

2

C

H

2

C

CH

2

.

H

3

C

.

H

2

CCH

2

CH

2

H H

H

2

C

CH

2

H

Br

+

+

+

..

.

..

..

Cl

..

.

..

..

Br

..

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

+

C

P

C

+

–

The following molecular orbital problems are more challeng-

ing than the earlier ones, and may be fairly regarded as

“special topics.” Nonetheless, they do provide some remark-

able insights, and for those who like orbital manipulation,

they will actually be fun. Just remember the “rules” outlined

on p. 34.

PROBLEM 1.61 Make a set of molecular orbitals very much like

the ones you made for linear HHH in Problem 1.60, but this

time use 2p orbitals, not 1s orbitals. Place one 2p orbital

between the other two. Use the molecular orbitals 2p 2p and

2p 2p that you constructed in Problem 1.25. Order the new

orbitals in energy.

PROBLEM 1.62 One can generate the molecular orbitals for

triangular H

3

simply by bending the orbitals generated in

Problem 1.60 to transform the linear molecule into the

bent one.

(a) Bend the three molecular orbitals for HHH to make the

orbitals for the triangle. Make careful drawings. Note that

as the old H(1) and H(3) come closer together in the

triangle they will create a new bonding or antibonding

interaction.

(b) Order the new molecular orbitals in energy by counting the

nodes.

PROBLEM 1.63 Which will be lower in energy, linear or trian-

gular What a sophisticated question! Yet, given the

answer to Problems 1.60 and 1.62, it is easy.

PROBLEM 1.64 In the chapter, we made the two molecular

orbitals for H

2

(p. 34), and in Problem 1.60 we used the two

molecular orbitals of H

2

and a 1s orbital to make HHH.This

time, generate the molecular orbitals for HHHH, linear H

4

,

from the molecular orbitals of two H

2

molecules placed end to

end. Remember: At this level of “theory,” you need only interact

orbitals closest in energy.

Order the new molecular orbitals in energy by counting nodes,

and place the proper number of electrons in the orbitals.

HHHH

+

–

HHHH

H

3

+

?

+

–