Jones M., Fleming S.A. Organic Chemistry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1.3 Covalent Bonds and Lewis Structures 19

WORKED PROBLEM 1.7 Draw Lewis structures for the following neutral species.

Use lines to indicate electrons in bonds,and dots to indicate nonbonding electrons.

*(a) CH

3

*(b) CH

2

(c) Br (d) OH (e) NH

2

(f)

ANSWER The first step is to determine the number of bonding electrons in each atom.

Then make the possible bonds and see how many electrons are left over. Because each

compound is neutral, the number of bonding electrons is equal to the atomic number

less the 1s electrons. For neutral hydrogen, there is always only the single 1s electron.

(a) Carbon has four bonding electrons and forms covalent bonds with three

hydrogens, each of which contributes a single electron. There is one electron

left over on carbon, which is shown as a dot in the Lewis structure:

(b) In carbon can form only two covalent bonds because only two hydro-

gen atoms are available.Two nonbonding electrons are left over:

WORKED PROBLEM 1.8 In each of the following compounds, there is at least one

multiple bond. Draw a Lewis structure for each molecule. Use lines to indicate

electrons in bonds, and dots to indicate nonbonding electrons.

(a) F

2

CCF

2

*(b) H

3

CCN (c) H

2

CO

(d) H

2

CCO (e) H

2

CCHCHCH

2

(f) H

3

CNO

(g)

ANSWER (b) If you did Problems 1.6 and 1.7, the methyl (CH

3

) group should be

familiar by now. Its three covalent bonds are constructed by sharing three of car-

bon’s four valence electrons with the single electrons of the three hydrogens:

The second carbon and the nitrogen bring four and five electrons, respective-

ly. Carbon–carbon and carbon–nitrogen covalent bonds can be formed, which

leaves two unshared electrons on carbon and four on nitrogen:

Formation of a triple bond between carbon and nitrogen completes the pic-

ture, and nitrogen is left with a nonbonding pair of electrons:

=

H

H

CH

C

.

.

N

.

.

..

H

H

CH

CN

..

H

H

CH

.

=

C

.

.

.

N

.

.

.

.

..

H

H

CH

C

.

.

N

.

.

..

C

..

..

..

.

H

H

CH

H

H

H

.

=

H

3

CO

O

‘

C

OH

H

H

=

..

..

C

H

H

C

..

..

CH

2

,

H

H

CH

..

.

.

..

..

H

H

CH

=

H

3

C

O

N

As we examine the nature of the bonding in the various molecules you will study

in organic chemistry, it is vital that you be able to draw Lewis structures quickly and

easily. It is also extremely important to be able to determine the charge on atoms,

sometimes referred to as a formal charge, in a given structure. For single atoms in

the second row of the periodic table, this process is easy as long as you remember

to count the two 1s electrons, which are never shown. Figure 1.22 gives Lewis struc-

tures and charge determinations for six species. Be sure you understand how the

charge is determined in each case.

20 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

=

=

=

1

H

1 Proton

2 Electrons

Net 1

–

Li

.

H

..

=

=

1

H

1 Proton

1 Electron

Neutral

H

.

H

.

=

1

H

1 Proton

0 Electrons

Net 1

+

H

H

=

9

F

9 Protons

2 1s Electrons

8 Nonbonding

electrons

9 Positive charges

10 Negative charges

3 Positive charges

3 Negative charges

6 Positive charges

5 Negative charges

Net 1

–

F

..

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

..

=

3

Li

3 Protons

2 1s Electrons

1 Nonbonding

electron

Neutral

Li

.

C

+

.

.

.

=

6

C

6 Protons

2 1s Electrons

3 Nonbonding

electrons

Net 1

+

–

+

= 1 Negative charge

= No negative charge

= 2 Negative charges

= 1 Positive charge

= 1 Positive charge

= 1 Positive charge

–

H

..

–

–

+

C

.

.

.

+

FIGURE 1.22 A few examples of

charge determination.

=

..

..

..

H

H

C

..

..

..

H

H

C

1 Proton

1 Shared electron

1

H

HH

H

H

CC

HH

..

=

=

9 Protons

2 1s Electrons

6 Nonbonding

electrons

1 Shared electron

9

F

F

..

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

= 9 Positive charges

9 Negative charges

Neutral F

6 Protons

2 1s Electrons

4 Shared electrons

6

C

= 6 Positive charges

6 Negative charges

Neutral C

= 1 Positive charge

= 1 Negative charge

Neutral H

H

H

FIGURE 1.23 Electron counting

in some simple molecules.

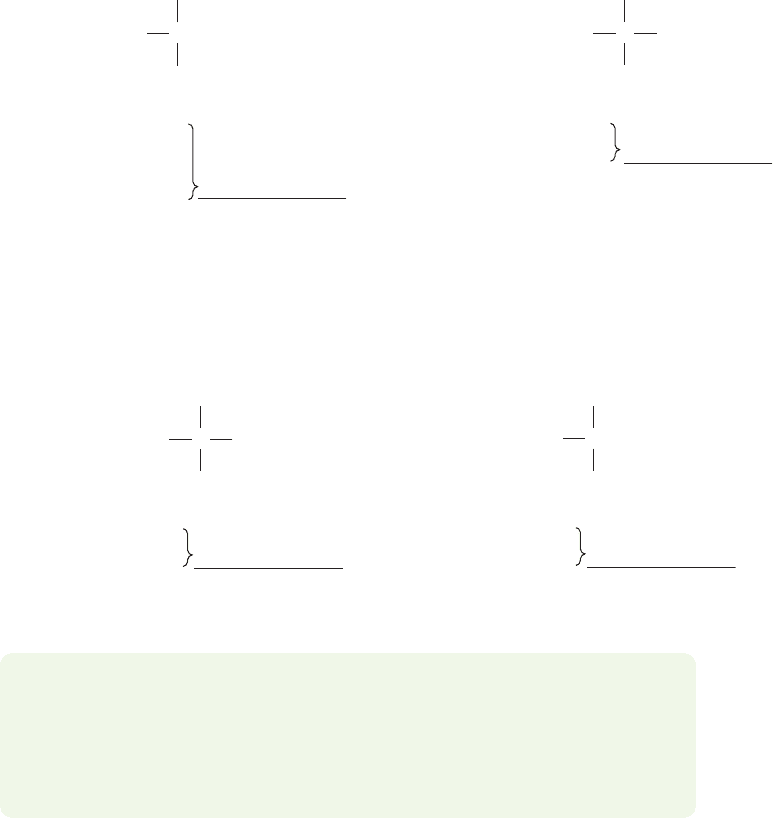

In molecules, the determination of charge is a bit harder because you must take

care to account for shared electrons in the right way. There are two steps to this

process.First, we need to count the electrons that the atom “owns.”Remember that

every second-row atom has a pair of unshown 1s electrons. Count all nonbonding

valence electrons as owned by the atom and count one electron for each bond to

the atom. The second step is to consider the atomic number (positive charge of

the nucleus) for that particular atom and subtract the number of electrons that

the atom owns (negative charges). The resulting value is the formal charge on the

atom. In for example, each hydrogen has only a share in the pair of electrons

binding the two nuclei, and therefore each hydrogen is neutral (Fig. 1.23).

H

2

,

1.3 Covalent Bonds and Lewis Structures 21

=

The methyl anion

6 Protons

2 1s Electrons

2 Nonbonding

electrons

3 Shared electrons

6

C

= 6 Positive charges

7 Negative charges

Net 1

–

H

H

H

C

..

..

..

..

..

H

H

H

C

=

The ammonium ion

7 Protons

2 1s Electrons

4 Shared electrons

7

N

= 7 Positive charges

6 Negative charges

Net 1

+

HH

H

H

N

+

..

..

..

..

HH

H

H

N

+

–

–

FIGURE 1.24 Examples of the

calculation of the charge on an atom

in a molecule.

=

5 Protons

2 1s Electrons

4 Shared electrons

5

B

= 5 Positive charges

6 Negative charges

Net 1

–

HH

H

H

B

..

..

..

..

HH

H

H

B

6 Protons

2 1s Electrons

3 Shared electrons

6

C

= 6 Positive charges

5 Negative charges

Net 1

+

=

H

H

H

C

..

..

..

H

H

H

C

–

–++

FIGURE 1.25 More calculations of

charge in molecules.

PROBLEM 1.9 Draw Lewis structures for the following charged species. In each

case, the charge is shown closest to the charged atom.

(a) (b) (c) (d) (e) (f)

(g) (Hint: Nitrogen is the central atom.)

+

NO

2

+

OH

3

+

CH

3

-

Cl

+

NH

4

-

BH

4

-

OH

In F

2

each fluorine has two 1s electrons, six nonbonding electrons, and a share in

the single covalent bond between the two fluorine atoms. This count gives a total

of nine electrons, exactly balancing the nine positive nuclear charges (9 9 0).

In each carbon has a pair of 1s electrons and a share in four cova-

lent bonds for a total of six. Because each carbon has a nuclear charge of 6, both

are neutral.

Let’s see why the carbon of the methyl anion is negatively charged

and why the nitrogen of the ammonium ion (

NH

4

) is positively charged

(Fig. 1.24). In the methyl anion, carbon has a pair of 1s electrons, two nonbond-

ing electrons, and a share in three covalent bonds, for a total of seven electrons.

The nuclear charge is only 6, and therefore the carbon must be negatively

charged (6 7 1).The nitrogen atom of the ammonium ion has two 1s elec-

trons plus one electron from each of the four covalent bonds, for a total of six.

The nuclear charge is 7, and therefore the nitrogen is positively charged

(7 6 1).

(

-

:

CH

3

)

H

2

C

P

CH

2

,

Figure 1.25 shows two more ions and works through the calculations of charge.

PROBLEM 1.10 Add charges to the following compounds wherever necessary:

(a) (b)

(c) (d)

(e) (f)

(g) (h)

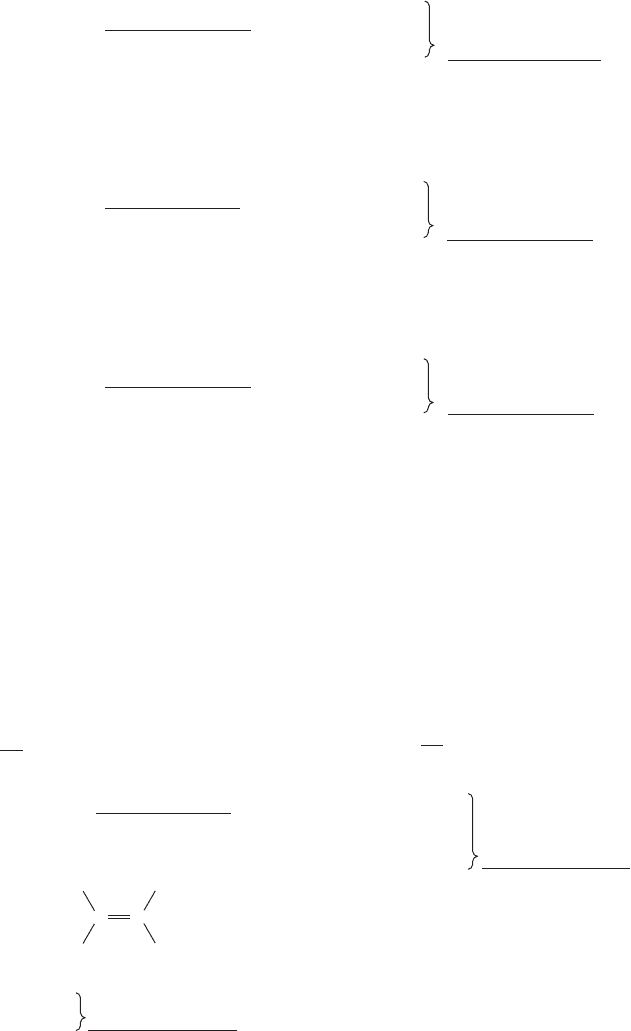

PROBLEM 1.11 Add electrons to complete the following Lewis structures. In each

case, the charge is placed as close as possible to the charged atom.

(a) (b)

(c) (d)

OH

3

(e)

OH (f)

NH

2

(g)

NH

2

(h)

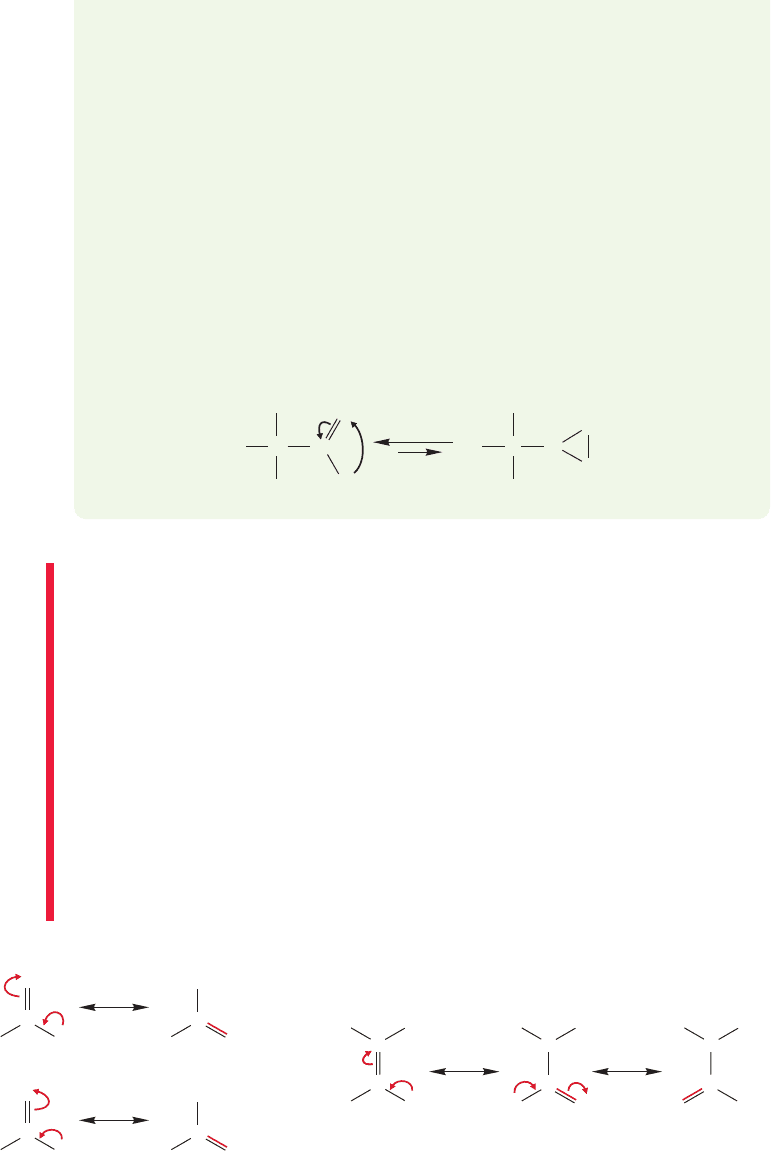

1.4 Resonance Forms

Often, there will be more than one possible Lewis structure for a molecule. This

statement is especially true for charged molecules, but it applies to many neutral

species as well. (You may already have encountered this phenomenon in comparing

your answers to Problems 1.9 and 1.10 with ours.) How do we decide which Lewis

structure is the correct one? The answer almost always is that neither Lewis struc-

ture is complete all by itself. Instead, the molecule is best described as a combina-

tion of all reasonable Lewis structures, that is, as a combination of resonance forms,

which are different electronic representations of the same molecule. Whether or

not a Lewis structure is reasonable, whether or not it is an important contributor,

will be addressed below. The word electronic is emphasized to remind you that the

only differences allowed in a set of resonance forms are differences in electron dis-

tribution. There can be no change in the position of the atoms in resonance forms.

Let’s use nitromethane, H

3

CNO

2

, as an example. The nitro group, NO

2

, is a

functional group, a collection of atoms that behaves more or less the same way wher-

ever it appears in a molecule. As we work through the various structural types of

molecules in organic chemistry, you will become familiar with many functional

groups, but right now, at this early stage, almost everyone needs to look up a struc-

ture now and then. The problem here is that the condensed formula NO

2

doesn’t

contain structural information about how the atoms are connected to one another.

For that matter, neither does CH

3

. Over time, you will become familiar with many

of the functional groups and will be able to write the appropriate structures with-

out even thinking about it. For now, you can consult the collection of functional

groups and their structures on the inside front cover of this book.

Even though nitromethane is a neutral molecule, there is no good way to draw

it without separated charges. Figure 1.26 shows a Lewis structure for nitromethane

that has the nitrogen positive and one of the oxygens negative. But this is not the

only Lewis structure possible! We can draw the molecule so the other oxygen bears

the negative charge. The two renderings of nitromethane in Figure 1.27 are reso-

nance forms of the molecule. Note that the arrangement of the atoms is identical

in the two forms. Resonance forms are different electronic representations of the

same molecule, not pictures of different molecules.The real molecule is the combi-

nation of all its resonance forms and is often called a resonance hybrid.

CH

3

O

C

q

N

+

O

H

HC

-

P

CH

2

-

CH

2

CH

3

+

CH

2

HN

.

.

P

C

P

N

.

.

H

:

N

.

.

H

2

H

2

C

P

O

.

.

::

OH

3

:

O

.

.

.

.

H

:

C

.

H

.

CH

3

:

CH

2

22 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

1.4 Resonance Forms 23

PROBLEM 1.12 Draw a Lewis structure for nitric acid ( ), and verify that

the nitrogen is positive and one of the oxygens is negative (see Fig. 1.26).

Neither Lewis structure in Figure 1.27 is completely accurate because in the

real nitromethane molecule, the two oxygens share the negative charge equally.

Thus, the two resonance forms in Figure 1.27 are equivalent electronic represen-

tations for nitromethane.Notice the special, double-headed arrow between the two

forms.This symbol is a resonance arrow, and in the notation of chemistry is used

exclusively to indicate resonance forms. Also notice the red, curved arrows in

Figure 1.27.These arrows are a notation used to show how we move a pair of elec-

trons from one point to another. In this case, such movement converts one reso-

nance form into the other. Using curved arrows to show how electrons move from

one point to another is called the curved arrow formalism. Other terms you might

encounter that are used to describe this type of analysis are arrow formalism or

electron pushing.

PROBLEM 1.13 Use the arrows to convert your Lewis structure for nitric acid

( Problem 1.12) into a resonance form.

WORKED PROBLEM 1.14 Draw another structure for nitromethane in which every

atom is neutral. Hint: There are only single bonds in this structure.

ANSWER You can arrive at the answer by using arrows to push electron pairs in

the following way:

+

–

H

H

H

C

O

O

N

..

..

..

..

..

..

H

H

H

C

..

..

..

..

O

O

N

HO

O

NO

2

,

HO

O

NO

2

H

N

H

H

C

O

O

..

..

..

..

..

–

8

O

8

O

7

N

+

8 Protons

2 1s Electrons

4 Nonbonding

electrons

2 Shared

electrons

= 8 Positive charges

8 Negative charges

Net neutral

8 Protons

2 1s Electrons

6 Nonbonding

electron

1 Shared

electrons

= 8 Positive charges

9 Negative charges

Net 1

–

6 Protons

2 1s Electrons

4 Shared

electrons

6

C

= 6 Positive charges

6 Negative charges

Neutral

7 Protons

2 1s Electrons

4 Shared

electrons

= 7 Positive charges

6 Negative charges

Net 1+

FIGURE 1.26 One electronic representation of nitromethane.

WEB 3D

H

3

C

N

O

Resonance arrow

Nitromethane

O

..

..

..

..

..

H

3

C

N

+

O

O

..

..

..

..

..

_

_

+

FIGURE 1.27 Two equivalent

resonance forms for nitromethane.

(continued)

Note that, as a new bond is formed between the two oxygen atoms, the two

charges originally on oxygen and nitrogen are canceled. Notice also the long

oxygen–oxygen bond. Remember: In drawing resonance forms, you move only

electrons, not atoms. The oxygen–oxygen distance must be the same in each

resonance form.

Is this cyclic form an important resonance form? Is it a good representation

of the molecule? The problem is the long bond between the oxygens. This bond

must be weak just because it is so long. In the language of organic chemistry, we

would say that the cyclic resonance form contributes little to the structure of

nitromethane.

Is the cyclic structure below a resonance form? Resonance involves different

electronic structures that do not differ in the positions of atoms.If atoms have been

moved, as in the figure below in which there is a normal oxygen–oxygen bond,the

two structures are in equilibrium and are not resonance forms.

Two things must be stressed here. First, although the curved arrows in Figure

1.27 have no physical significance, they do constitute an extraordinarily important

bookkeeping device. They map out the motions of electrons. But be careful—these

arrows, useful as they are, do not represent more than a bookkeeping process. We

will use curved arrows throughout this book, and all organic chemists use them to

keep track of electron movement, not only in drawing resonance forms but in writ-

ing chemical reactions as well. Being able to draw resonance forms quickly and

accurately is an essential skill for anyone wishing to master organic chemistry.

The second point to be stressed is that the bookkeeping represented by curved

arrows in resonance forms is accomplished by moving or “pushing”pairs of electrons.

Be careful when doing this sort of thing not to violate the rules of valence, not to

make more bonds than are possible, for this mistake is easy to make. Figure 1.28

gives some examples of this kind of electron-pair pushing in molecules best repre-

sented as combinations of resonance forms.

–

+

H

H

H

C

O

O

N

..

..

..

..

..

H

H

H

C

..

..

..

..

..

O

O

N

24 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

C

O

O

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

–

–

–

–

H

3

CH

3

C

C

O

O

..

..

C

O

..

..

..

..

..

H

3

CH

3

CCH

2

C

O

C

H

2

.. ..

+

C

N

HH

H

2

NNH

2

..

..

+

C

N

HH

H

2

NNH

2

..

..

+

C

N

HH

H

2

NNH

2

FIGURE 1.28 Resonance forms.

CONVENTION ALERT

It is important to be extremely clear on the following point about resonance struc-

tures.Nitromethane does not spend half its time as one resonance form and half as the

other. There is no equilibration between the resonance forms. Nitromethane is best described

1.4 Resonance Forms 25

as the combination of the two electronic structures shown in Figure 1.27. In

nitromethane, the two resonance forms are equivalent because there is no differ-

ence between having the negative charge on one oxygen or the other, and thus

nitromethane can be reasonably described as a 50:50 combination (average) of the

two forms.

Here’s an analogy that might help: Frankenstein’s monster was always a mon-

ster. One might describe that poor constructed creature as part monster and part

human, but he was always that combination—he did not oscillate between the

two. In chemical terms, one would say that Frankenstein was a resonance hybrid

of monster and human. On the other hand, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde were in equi-

librium. When the good Dr. Jekyll drank the potion, he became the monstrous

Hyde. Later, when the potion wore off, he reverted to Jekyll. Part of the time he

was Jekyll, and part of the time he was Hyde. The two were in equilibrium, not

resonance.

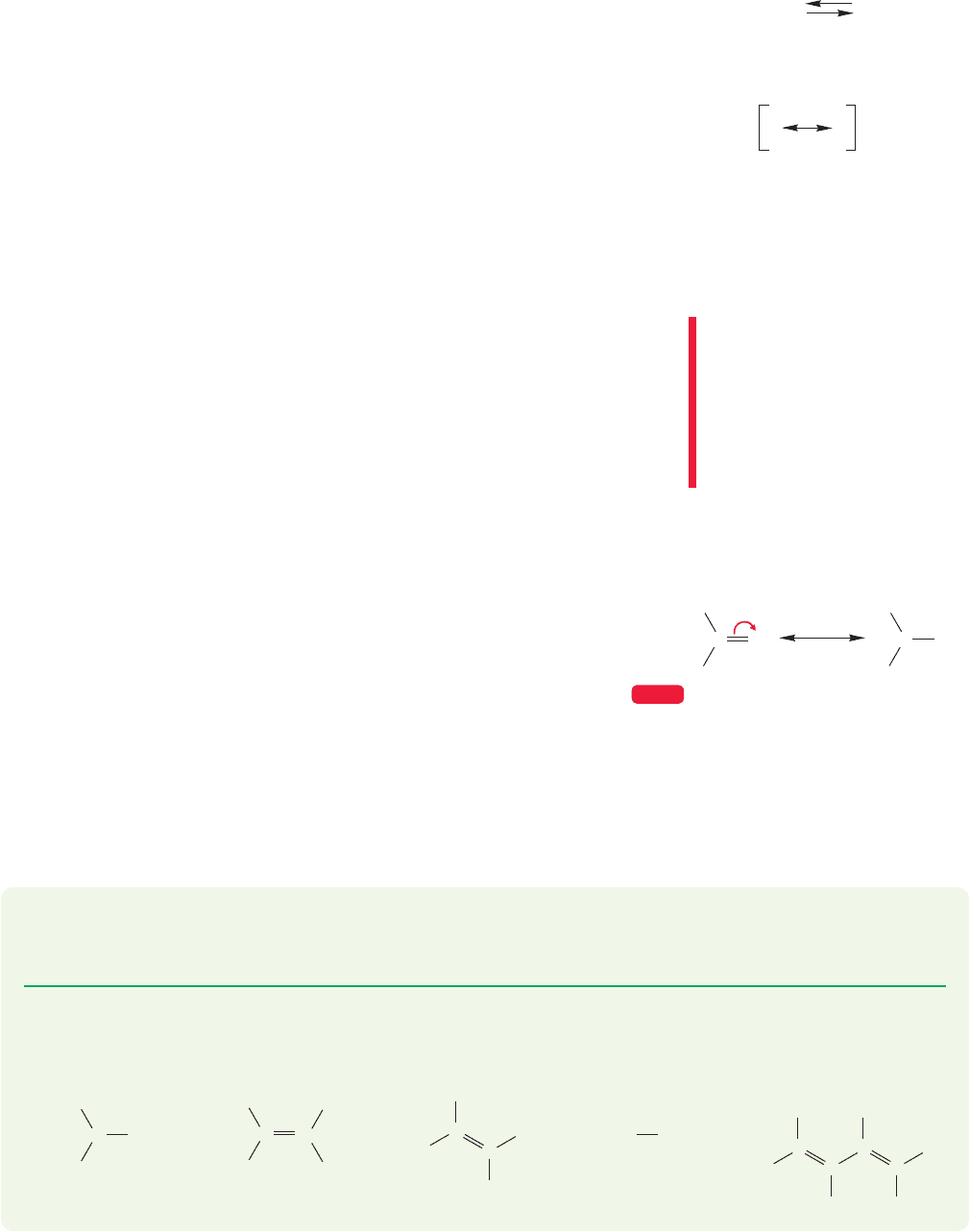

The special double-headed arrow ( ) used in Figures 1.27 and 1.28 is reserved

for resonance phenomena and is never used for anything but resonance. A pair of

arrows ( ) indicates equilibrium, the interconversion of two chemically distinct

species, and is never used for resonance (Fig. 1.29). This point is most important in

learning the language of organic chemistry. It is difficult because it is arbitrary.

There is no way to reason out the use of the different kinds of arrows; they simply

must be learned.

The carbon–oxygen double bond in formaldehyde ( , Fig. 1.30), gives

us another opportunity to write resonance forms. In the resonance form on the left

in Figure 1.30, carbon has a pair of 1s electrons and shares in four covalent bonds;

therefore it is neutral (6 6 0). Oxygen has a pair of 1s electrons, four nonbond-

ing electrons,and a share in two covalent bonds,for a total of eight electrons

(8 8 0). Oxygen is also neutral. However, we can push electrons to gen-

erate the resonance form shown on the right in Figure 1.30, in which the

carbon is positive and the oxygen negative.The real formaldehyde molecule

is a combination, not a mixture, of these two resonance forms, a resonance

hybrid. Because charge separation is energetically unfavorable, these two resonance

forms do not contribute equally to the structure of the formaldehyde molecule. Still,

neither by itself is a perfect representation of the molecule, and in order to repre-

sent formaldehyde well, both electronic descriptions must be considered.

Formaldehyde is the weighted average of the two resonance forms in Figure 1.30.

How we determine a weighted average is what we look at next.

PROBLEM 1.15 There is a third resonance form for formaldehyde, but it con-

tributes very little to the structure and is usually ignored. Can you find it and

explain why it is relatively unimportant?

PROBLEM 1.16 Use the arrow formalism to convert each of the following Lewis

structures into another resonance form. Notice that part (e) of this question asks

you to do something new—to move electrons one at a time in writing Lewis forms.

H

2

C

P

O

Z

U

Z

U

CONVENTION ALERT

A B

Two chemically distinct species

One species, E, with two Lewis

descriptions, C and D

CDE

=

FIGURE 1.29 The difference between

equilibrium (two different species, A

and B; two arrows) and resonance

(different electronic representations,

C and D, for the same molecule, E;

double-headed arrow).

FIGURE 1.30 Formaldehyde.

WEB 3D

H

Resonance forms for formaldehyde

H

C

O

..

..

..

..

..

H

H

CO

+

–

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

..

C

H

3

C

H

3

C

CH

2

H

3

NBH

3

C

CH

3

CH

3

NB

+

–

C

H

H

CH

2

+

+

–

–

H

2

C

C

.

C

H

C

H

H

H

C

CH

2

.

–

+

H

3

C

H

3

C

O

..

..

..

WORKED PROBLEM 1.17 Use the arrow formalism to write resonance forms that

contribute to the structures of the following molecules:

ANSWER (c) As we have seen, it is not only electron pairs (nonbonding electrons)

that can be redistributed (pushed) in writing resonance forms, but bonding electrons

as well. In this case, a pair of electrons in a carbon–carbon double bond is moved.

The positive charge on the right-hand carbon disappears, but reappears on the left-

hand carbon. In the real structure,the two carbons share the positive charge equal-

ly, each bearing one-half the charge. The structure is sometimes written with

dashed bonds to show this sharing:

It is important to be able to estimate the relative importance of resonance forms

in order to get an idea of the best way to represent a molecule. To do so, we can

assign a weighting factor,c, to each resonance form.The weighting factor is a num-

ber that indicates the percent contribution of each resonance form to the resonance

hybrid. Some guidelines for assigning weighting factors are listed below. Fortunately,

this is an area in which common sense does rather well.

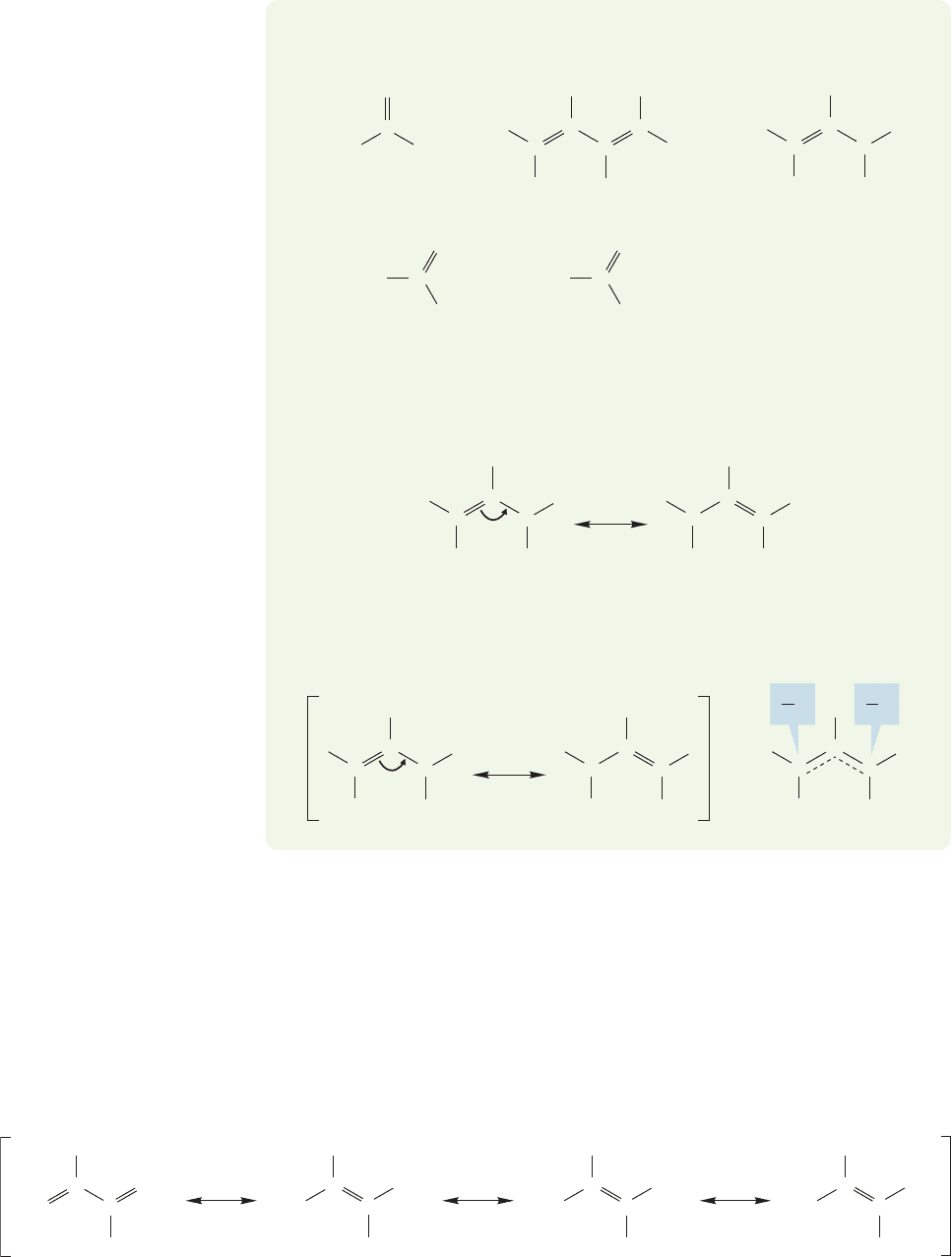

1. The more bonds in a resonance form, the more important a contributor the form

is. For example, 1,3-butadiene can be written as a resonance hybrid of four struc-

tures (Fig. 1.31).

Summary structure

C

C

H C

H

H

H

H

+

C

C

H C

H

H

H

H

+

C

C

H C

H

H

H

H

+

=

1

2

+

1

2

+

C

C

H C

H

H

H

H

+

C

C

H C

H

H

H

H

+

(c)

(a)

(b)

*(c)

(d)

(e)

H

H

C

NH

2

O

O

CH

3

C

–

C

C

H C

H

H

C

H

H

H

C

C

H C

H

H

H

H

+

+

..

..

..

..

..

OH

OH

CH

3

C

+

..

..

..

26 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

H

2

C

C

C

CH

2

+

–

A

H

2

C

C

C

CH

2

H

2

C

C

C

CH

2

BC

–

+

H

2

C

C

C

CH

2

C'

..

..

.

.

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

FIGURE 1.31 Four resonance forms contributing to 1,3-butadiene. Form A is by far the best.

1.4 Resonance Forms 27

It is reasonably well described by form A, which has a total of 11 bonds. Forms

B, C, and C each contain 10 bonds, and will contribute far less than A to the actu-

al 1,3-butadiene structure. Forms C and C are equivalent (this is why they are

labeled C and C rather than C and D) and contribute equally to the hybrid. Even

though A is clearly the major contributor, this does not mean that B, C, and C do

not contribute at all! It simply means that in our equation

Butadiene c

1

(A) c

2

(B) c

3

(C) c

3

(C)

the weighting factor c

1

is much larger than the other coefficients. Therefore,

1,3-butadiene looks much more like A than B, C,or C.

2. Separation of charge is bad. In Figure 1.31, the neutral resonance forms A and B

contribute more to the resonance hybrid than C or C, both of which require a

destabilizing separation of charge. (Form B contributes less than form A, as noted

in guideline 1, because it has fewer bonds.)

3. In ions,

delocalization of electrons (distributing them over as many atoms as pos-

sible) is especially important. Delocalization of electrons is a process that allows

more than one atom to share electrons and it is almost always stabilizing. Electrons

are like water, if allowed to spread out, they will. The allyl cation is a good exam-

ple—the two end carbons each bear one-half of the positive charge (Fig. 1.32).

=

H

H

2

CCH

2

C

H

+

H

2

CCH

2

C

H

+

AA'

c

1

c

2

H

2

C

CH

2

C

+

FIGURE 1.32 The allyl cation is an

equal combination of A and A.

H

H

CCH

2

Cl

H

H

CCH

2

Cl

+

+

..

..

..

..

..

c

2

c

1

FIGURE 1.33 In this carbocation, the

charge is shared by carbon and

chlorine.

H

2

C

CH

2

=

C

H

H

2

CCH

2

C

H

–

H

2

CCH

2

C

H

–

H

2

CCH

2

C

H

–

....

(–)

H

2

C

O

=

C

H

–

H

2

C

C

H

–

H

2

C

C

H

–

..

..

..

..

..

..

c

2

c

1

AB

OO

In this case, c

1

> c

2

c

2

c

1

In this case, c

1

= c

2

1

2

–

1

2

–

(a)

(b)

FIGURE 1.34 (a) The allyl anion.

(b) The enolate anion.

The electrons of the double bond have spread into the empty p orbital.The ion

shown in Figure 1.33 is another good example.Here the charge is shared by the car-

bon and the chlorine, as the two resonance forms show.

4. Electronegativity is important. In the allyl anion (Fig. 1.34a), for example, there

are two equivalent resonance forms. As in the allyl cation, the charge resides

equally on the two end carbons. Figure 1.34a shows two summary structures

for the allyl anion. In one, each of the two end carbons is shown with half a

negative charge; in the other, one resonance form is drawn, and the positions

sharing the charge are indicated by drawing the charge in parentheses ().

The related enolate anion, in which one CH

2

of allyl is replaced with an oxygen

(Fig. 1.34b), also has two resonance forms, but they do not contribute equally

because they are not equivalent. Each has the same number of bonds, and so

we cannot choose the better representation that way. However, form A has

the charge on the relatively electronegative oxygen while form B has it on

carbon, which is considerably less electronegative than oxygen. Form A is the

better representation for the enolate anion, although both forms contribute.

Mathematically, we would say that the weighting factor for A,c

1

, is larger than

that for B,c

2

.

5. Resonance forms that are equivalent contribute equally to a resonance hybrid. The

two forms of nitromethane in Figure 1.27 and the two forms of the allyl cation

(A and A) in Figure 1.32 are good examples. In both cases the resonance forms are

completely equal to each other (indistinguishable, same number of bonds, same

number of charges, charges on same atoms).

In cases such as these, the weighting factors for the two forms, c

1

and c

2

, must

be equal. An equation to represent the mathematics involved in our allyl cation

example is

Allyl c

1

(form A) c

2

(form A)

where c

1

is the weighting factor for resonance form A,c

2

is the weighting factor for

form A, and c

1

c

2

.

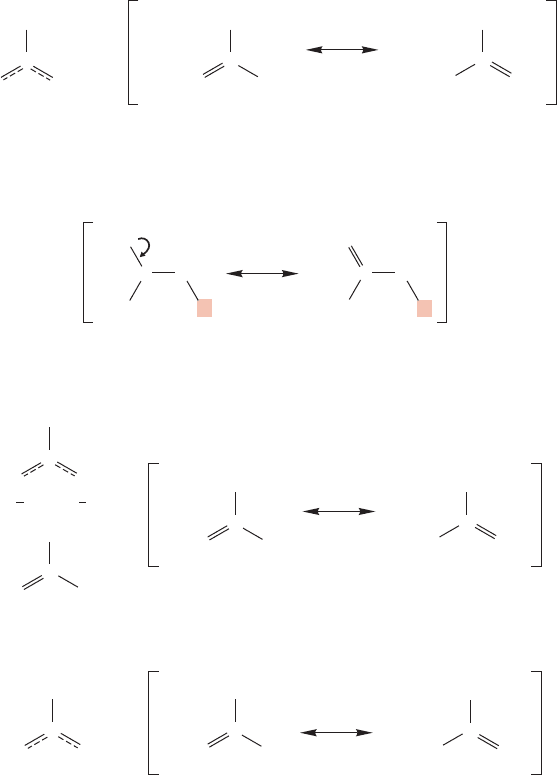

6. All resonance forms for a given species must have the same number of paired and

unpaired electrons. As we saw in Figure 1.5, two electrons occupying the same

orbital must have opposite spin quantum numbers. Most organic molecules,

including our example molecule 1,3-butadiene, have all paired electrons.

Therefore, resonance forms for 1,3-butadiene must also have all paired electrons.

Consider form B in Figure 1.31. It is often the convention to emphasize that all

electrons are paired in this molecule by appending electron-spin arrows alongside

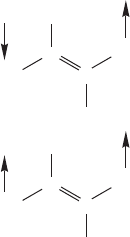

each single electron in this form (Fig. 1.35). Opposed arrows ( and ) indicate

paired spins, arrows in the same direction ( and or and ) indicate parallel

(same-direction) spins.

[[\\

\[

28 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

C

C

CH

2

H

2

C

H

2

C

.

.

C

C

CH

2

.

.

The opposing arrows indicate

that the spin quantum numbers

of the two electrons are different;

this is a resonance form of

1,3-butadiene

The identical arrows indicate

that the spins of the two electrons

are the same; this is not a

resonance form of 1,3-butadiene

H

H

H

H

FIGURE 1.35 In 1,3-butadiene, all

electrons are paired, and all resonance

forms contributing to the structure

must also have all electrons paired.