Jones M., Fleming S.A. Organic Chemistry

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

1.2 Atoms and Atomic Orbitals 9

6

C

(a)

2p

2s

1s

(b) (c) 1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2p

y

Lowest energy

Energy

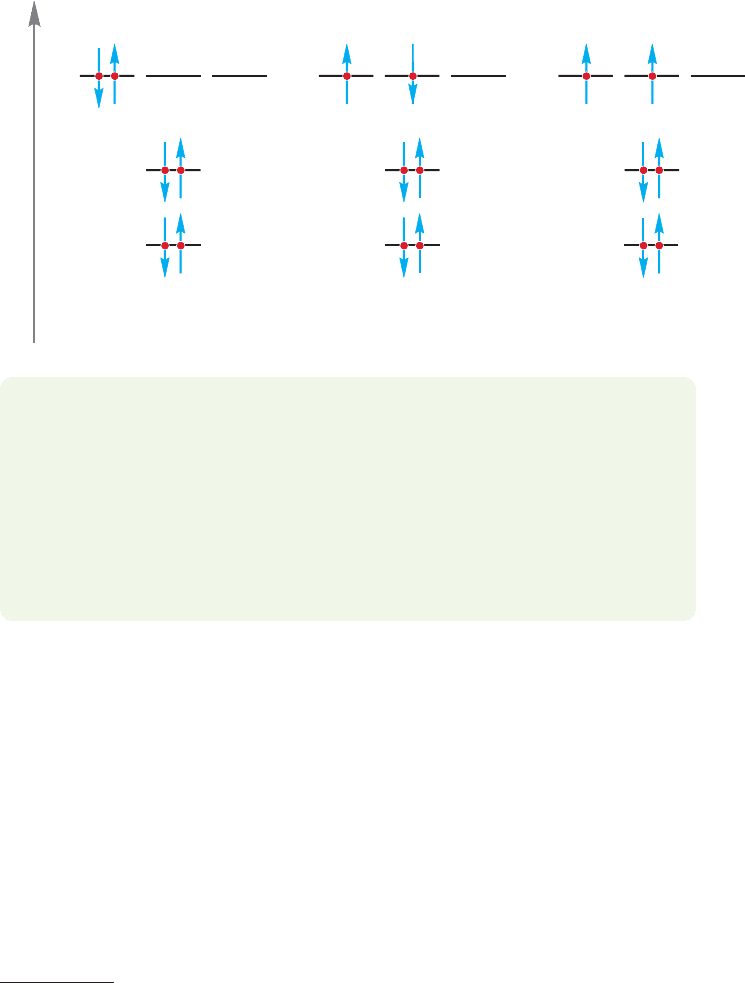

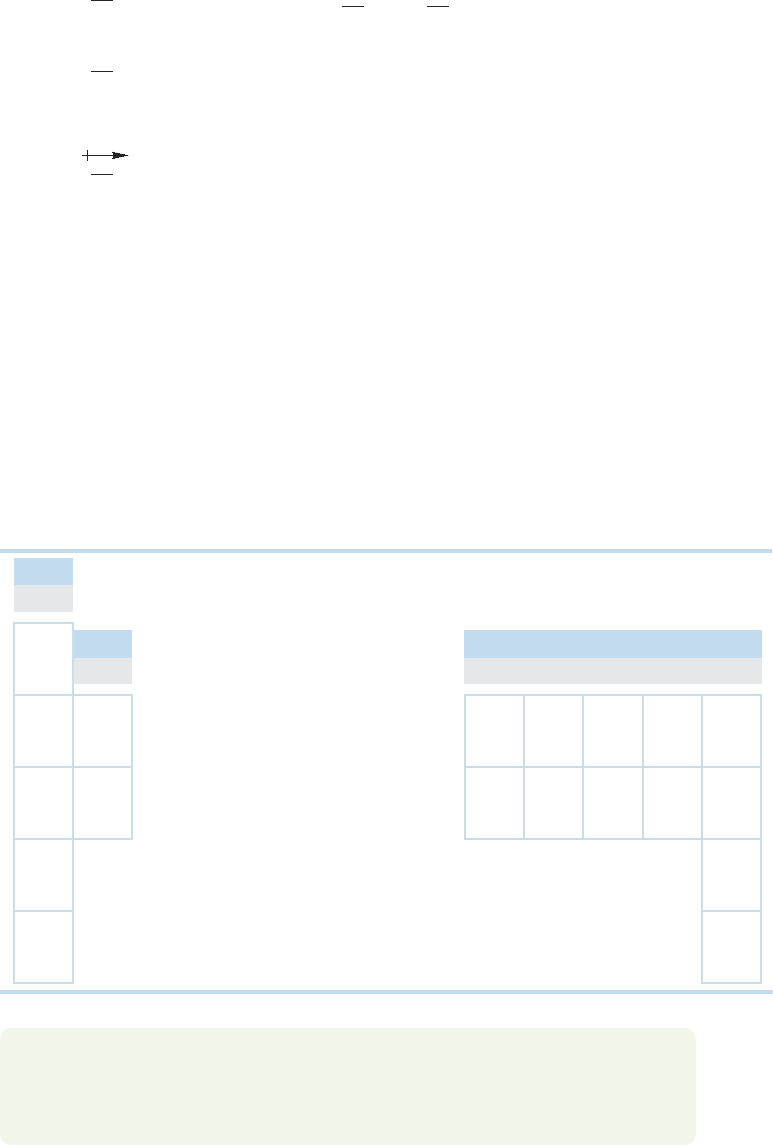

FIGURE 1.5 An application of

Hund’s rule.The electronic

configuration with the largest

number of parallel (same

direction) spins is lowest in

energy. Note the use of the arrow

convention to show electron spin.

reasonable assumption that we should fill the available orbitals in order of their ener-

gies, starting with the lowest-energy orbital. To form these descriptions of neutral

atoms, we add electrons until they are equal to the number of protons in the nucle-

us. Table 1.6 gives the electronic configurations of H, He, Li, Be, and B.

For carbon, the atom after boron in the periodic table, there is a choice to be

made in adding the last electron.The first five electrons are placed as in boron, but

where does the sixth electron go? One possibility would be to put it in the same

orbital as the fifth electron to produce the electronic configuration

(Fig. 1.5a). In such an atom, the spins of the two electrons in the 2p

x

orbital must

be paired (opposite spins).

6

C = 1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

WORKED PROBLEM 1.1 Explain why the two electrons in the 2p

x

orbital of carbon

must have paired spins ( and ).

ANSWER

6

Because they are in the same orbital (2p

x

), both electrons have the same

values for the three quantum numbers n, l, and m

l

(n 2, l 1, m

l

1, 0,

or 1).If the spin quantum numbers were not opposite,one the other

the two electrons would not be different from each other! The Pauli principle (no

two electrons may have the same values of the four quantum numbers) ensures that

two electrons in the same orbital must have different spin quantum numbers.

Alternatively, the sixth electron in the carbon atom could be placed in another

2p orbital to produce (Fig.1.5b).The only difference is the pres-

ence of two electrons in a single 2p orbital in Figure 1.5a, versus

one electron in each of two different 2p orbitals in Figure 1.5b.

The three 2p orbitals are of equal energy (because each has n 2, l 1), and so

how is one to make this choice? Electron–electron repulsion would seem to make

the second arrangement the better one,but there is still another consideration.When

two electrons occupy different but equi-energetic orbitals, their spins can either be

paired ( ) or unpaired ( ). Hund’s rule (Friedrich Hund, 1896–1997) states

that for a given electron configuration,the state with the greatest number of unpaired

(parallel) spins has the lowest energy. So the third possibility for carbon’s sixth elec-

tron (Fig. 1.5c) is actually the best one in this case. Essentially, giving the two

\\\[

(

6

C = 1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

p

y

)

(

6

C = 1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

)

6

C = 1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2p

y

-1>2,+1>2,

-1>2+1>2(

6

C = 1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

)

6

Worked Problems are answered in whole or in part in the text.When only part of a problem is worked, that

part will have an asterisk. Complete answers can be found in the Study Guide.

10 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

electrons the same spin ( ) ensures that they cannot occupy the same orbital and

tends to keep them apart. So, Hund’s rule tells us that the configuration

with parallel spins for the two electrons in the 2p orbitals is the

lowest-energy state for a carbon atom.

PROBLEM 1.2 Explain why the fifth and sixth electrons in a carbon atom may not

occupy the same orbital as long as they have parallel spins.

Now we can write electronic configurations for the rest of the atoms in the sec-

ond row of the periodic table (Table 1.7). Notice that for nitrogen we face the same

kind of choice just described for carbon.Does the seventh electron go into an already

occupied 2p orbital or into the empty 2p

z

orbital? The configuration in which the

and orbitals are all singly occupied by electrons that have the same spin

is lower in energy than any configuration in which a 2p orbital is doubly occupied.

Again, Hund rules!

PROBLEM 1.3 Write the electronic configurations for the atoms in the third row

in the periodic table, through

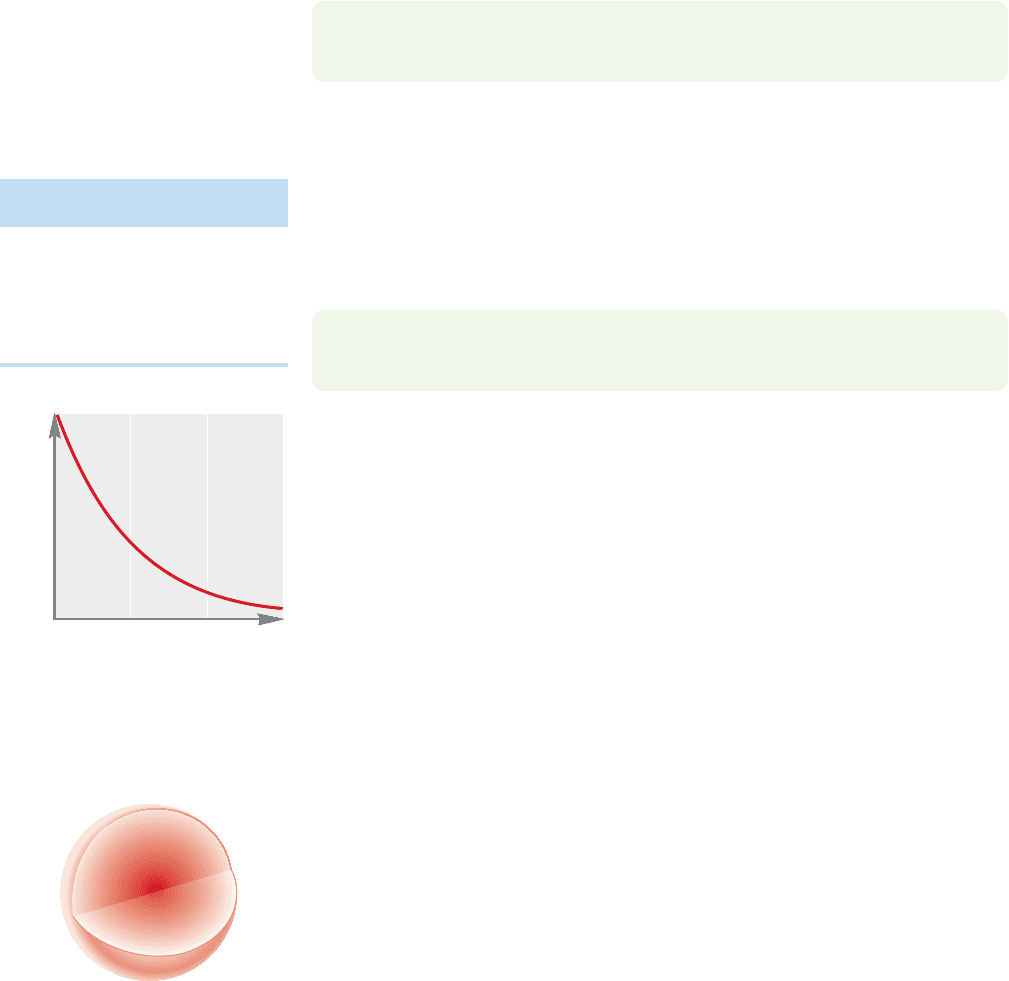

In order to understand the properties and reactions of the molecules you will

encounter in organic chemistry, it will be necessary to know the shapes of the mol-

ecules. It turns out that molecular shape can be best understood by knowing where

the electrons are. Recall that ψ

2

is related to the electron density around a nucleus.

Therefore a graph that plots ψ

2

as a function of r, the distance from the nucleus,

can describe the shape of the orbital. Figure 1.6 plots ψ

2

as a function of r for the

lowest-energy solution to the Schrödinger equation, which describes the 1s orbital.

The graph shows that the probability of finding an electron falls off sharply in all

directions (x, y, and z) as we move out from the nucleus. Because there is no direc-

tionality to r, we find the 1s orbital is symmetrical in all directions—that is, it is

spherical. As noted earlier, it is the quantum number l that is associated with orbital

shape, and all s orbitals, for which l always equals zero, are spherically symmetric.

Note also that the electron density never goes to zero, that there is a finite (though

very, very small) probability of finding an electron at a distance of several angstroms

from the nucleus.

Figure 1.7 translates the two-dimensional graph of Figure 1.6 into a three-

dimensional picture of the 1s orbital, a spherical cloud of electron density that has

its maximum near the nucleus. Although this cloud of electron density is shown as

bound by the spherical surface at some arbitrary distance from the nucleus, it does

not really terminate sharply there. This spherical boundary surface simply indicates

the volume within which we have a high probability of finding the electron. We can

choose to put the boundary at any percentage we like—the 95% confidence level,

the 99% confidence level, or any other value. It is this picture that we have been

approaching throughout these pages. The representation of the electron density in

Figure 1.7 is the one you will probably remember best and the one that will be most

useful in our study of chemical reactions.This sphere centered on the nucleus is the

region of space occupied by an electron in the 1s orbital.

Figure 1.6 correctly gives the probability of finding an electron at a particular

point a distance r from the nucleus, but it doesn’t recognize that as r increases, a

given change in r (denoted by the symbol ) produces a greater volume of space¢r

18

Ar.

11

Na

2p

z

2p

y

,

2p

x

,

6

C = 1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

p

y

\\

TABLE 1.7 Electronic

Descriptions of Some Atoms

in the Second Row

Atom Electronic

Configuration

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

2p

y

2

2p

z

2

10

Ne

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

2p

y

2

2p

z

9

F

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

2p

y

2p

z

8

O

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2p

y

2p

z

7

N

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2p

y

6

C

FIGURE 1.6 A plot of ψ

2

versus

distance r for hydrogen. Note that

the value of ψ

2

does not go to zero,

even at very large r.

(1s)

ψ

2

(1s)

Distance from nucleus r

FIGURE 1.7 A three-dimensional

picture of the 1s orbital. The surface

of the sphere denotes an arbitrary

cutoff.

1.2 Atoms and Atomic Orbitals 11

and thus a greater number of points where the electron might be. To see why this

is so, look at Figure 1.8. Even though the increase, , for each concentric circle is

the same, the volume is much greater for the outer spherical shell. The change in

volume is not linear with the change in radius.

We account for this increasing influence of with the graph shown in Figure

1.8. Here the horizontal axis is again r, but the vertical axis accounts for

the volume of the sphere. The resulting graph gives a picture of the probability of

finding an electron at all points at a distance r from the nucleus. This new picture

takes account of the increasing volume of spherical shells of thickness as the dis-

tance from the nucleus, r, increases.

Summary

1. An electron is described by four quantum numbers (n, l, m

l

, and s).

2. Electrons are filled into the available orbitals starting with the lowest-energy

orbital (the aufbau principle).

3. An orbital can contain only two electrons,which must have paired spin quantum

numbers, and

4. The quantum number l specifies the shape of the orbital, and all s orbitals have

spherical symmetry.

5. We can do no better than to say that within some degree of certainty that an

electron is within a certain volume of space.ψ

2

gives us the shape of that volume.

6. The cutoff point for our degree of certainty is arbitrary because, as Figures 1.6

and 1.8 show, the chance of an electron being far from the nucleus is never zero.

As noted earlier, the mathematical function ψ that describes an atomic orbital

has many of the properties of waves.There are,for example, the hills and valleys evi-

dent in waves in liquids and in a vibrating string. Hills correspond to regions for

which the mathematical sign of ψ is positive, and valleys correspond to regions for

which the mathematical sign of ψ is negative. In a vibrating string, when we pass

from a length of string in which the amplitude is positive to one where it is nega-

tive, we find a stationary point called a node. Nodes also appear in wave functions

at the points at which the sign of ψ changes, where ψ Of course, if ψ

then ψ

2

and so the probability of finding an electron at a node is also zero. In

an atomic orbital, therefore, a node is a region of space in which the electron den-

sity is zero.The number of nodes in an orbital is always one fewer than n, the prin-

cipal quantum number. Thus, the n 1 orbital (1s) has no nodes, all n 2 orbitals

have a single node, all n 3 orbitals have two nodes, and so on. As we turn our

attention from the 1s orbital to higher-energy orbitals, we will have to pay atten-

tion to the presence of nodes.

= 0,

= 0,= 0.

s =-1>2.s =+1>2

¢r

14πr

2

ψ

2

2

¢r

¢r

r

⌬r

0.530

1s Orbital

1s Orbital

1s Orbital

4πr

2

ψ

2

r (A

)

FIGURE 1.8 The graph on the left

shows a slice through the three-

dimensional 1s orbital. At relatively

low values of r (short distance from

the nucleus) will contain a smaller

volume than at higher values of r

(larger distance from the nucleus). The

outer spherical shell contains a greater

volume than the middle shell even

though they are both wide.This

plot is weighted for the increasing

influence of as r gets larger.¢r

¢r

¢r

12 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

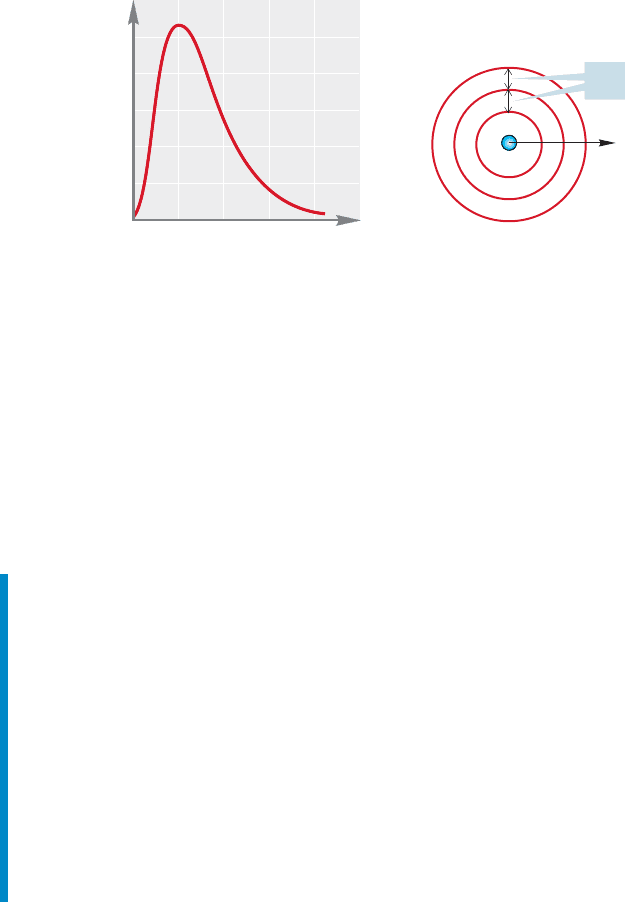

The next higher energy orbital is the 2s (n 2, l 0). Because n 2, there

must be a single node in this orbital, and we expect spherical symmetry, as with

all s orbitals. Figure 1.9a shows a plot of versus r. Figure 1.9b is a

three-dimensional representation of the 2s orbital, which shows a spherical node,

representing the spherical region at which ψ and ψ

2

are zero.

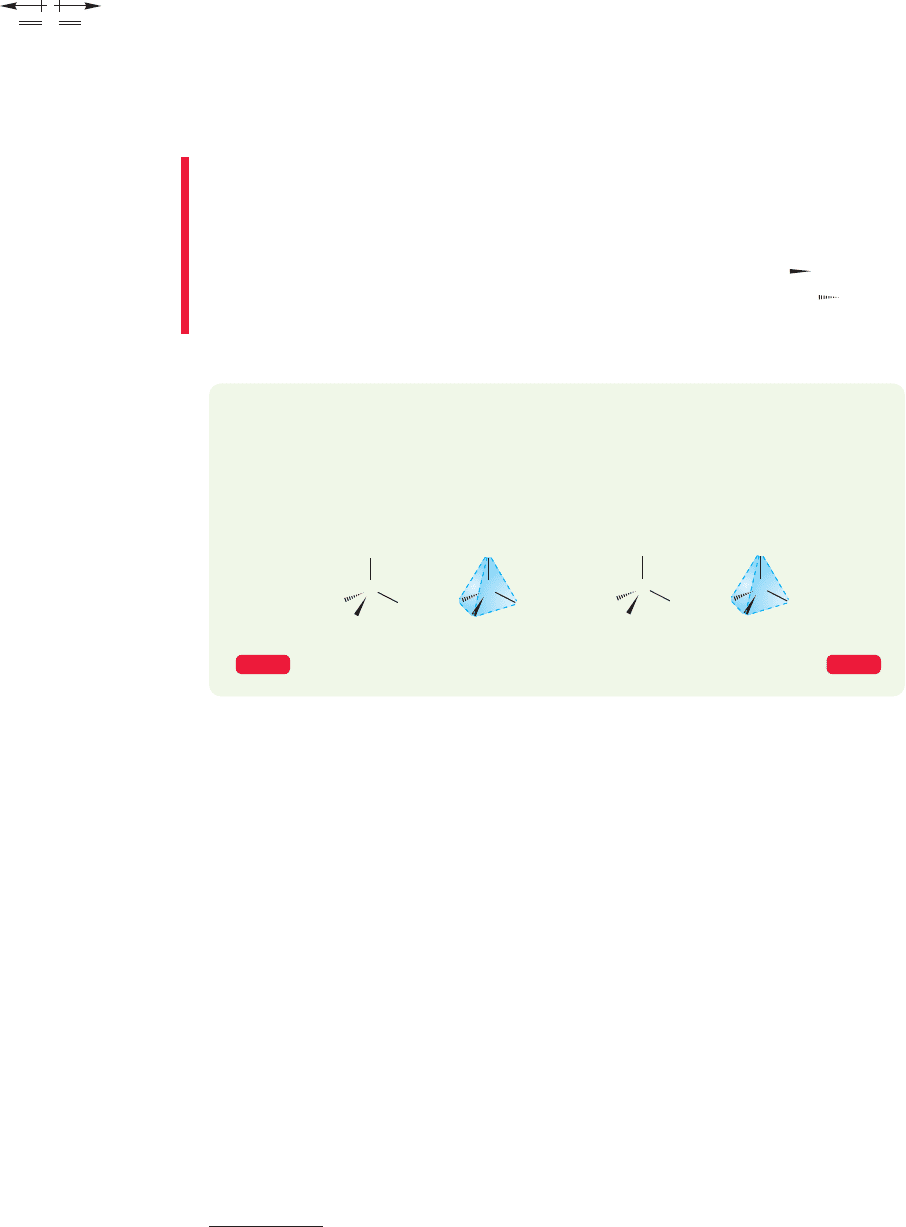

When n 2, l can equal 1 as well

as zero. As described on page 7, the

quantum number combination of n

2, l 1 gives the and

orbitals, each of which must possess a

single node.Because l is not zero,the 2p

orbitals are not spherically symmetrical.

As you may have guessed from the x, y,

z designations, the 2p orbitals are

directed along the x, y, and z axes of a

Cartesian coordinate system (Fig. 1.10).

Each 2p orbital is made up of two lobes

that are slightly flattened spheres, and

the orbital as a whole is shaped roughly like a dumbbell.The node is the plane sep-

arating the two halves of the dumbbell. In one lobe of the orbital, the sign of the

wave function is positive; in the other the sign is negative.To avoid confusion with

electrical charge these signs are usually indicated by a change of color rather than

and . The three 2p orbitals together are shown in Figure 1.11. As you can see,

2p

z

2p

y

,

2p

x

,

4πr

2

ψ

2

FIGURE 1.9 (a) A plot of ψ

2

versus

r for a 2s orbital and (b) a cross

section through the orbital.

1r2

4πr

2

ψ

2

0123456

r ()

Node

2s Orbital

2s Orbital

2s Orbital

Nodal sphere where

the probability density

is zero.

A

(a) (b)

y

y

y

z

z

z

x

x

x

2p

z

2p

y

2p

x

yz plane xz plane

xy plane

FIGURE 1.10 An accurate three-

dimensional representation of three

2p orbitals. Note the nodal planes

separating the lobes where the sign of

ψ differs. Color is used to emphasize

the opposite signs of the lobes.

2p

x

2p

y

Nodal

plane

2p

z

y

y

y

z

z

z

x

x

x

Sign of

ψ = +

Sign of

ψ = –

FIGURE 1.11 A schematic three-

dimensional representation of three

2p orbitals, shown separately and in

combination.

Summary

Electrons in atoms are confined to certain volumes of space, and these volumes

are not all alike in shape. A dumbbell-shaped 2p orbital is quite different from a

spherical 2s orbital, for example.

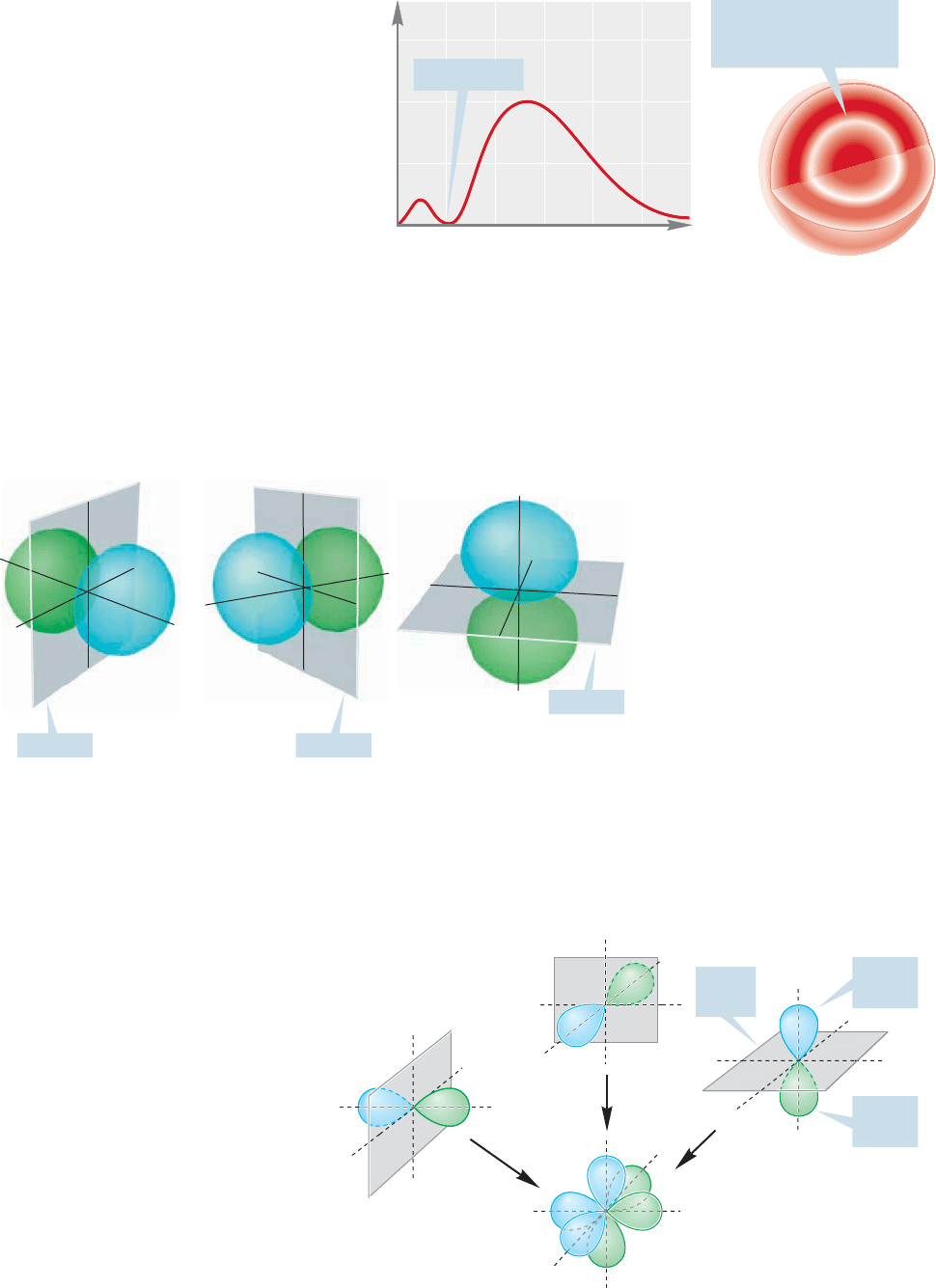

1.3 Covalent Bonds and Lewis Structures

The formation of molecules through covalent bonding is the subject of much of the

remainder of this chapter. Because a covalent bond is formed by the sharing of a pair

of electrons between two atoms, the bond is shown either as a pair of dots between two

atoms or as a line joining the two (Fig.1.13).These two-electron bonds will be promi-

nent in almost all of the molecules shown in this book. For many simple molecules,

even the line between the atoms is left out, and the compound is written simply as A

2

or AB. You are left to supply mentally the missing two electrons.

1.3 Covalent Bonds and Lewis Structures 13

1s Orbitals

not shown

...

1

H

1s

2

He

1s

2

3

Li

1s

2

2s

4

Be

1s

2

2s

2

5

B

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

6

C

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2p

y

7

N

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2p

y

2p

z

8

O

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

2p

y

2p

z

9

F

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

2p

y

2

2p

z

10

Ne

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

2p

y

2

2p

z

2

.

.

.

..

..

.

.

.

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

.

.

..

..

.

.

..

FIGURE 1.12 Schematic pictures of

the first 10 atoms in the periodic

table. Each dot represents an

electron, although the 1s electrons for

the atoms past He are not shown.

.

Two

separate

atoms

Shared electron

pair in the A

2

molecule

+

=

=

A

AA

AA

A

2

.

A

..

FIGURE 1.13 Bonding through the

sharing of electrons is not ionic, but

covalent. Covalent bonding can also

result in stable electronic

configurations.

the stylized dumbbells used to represent 2p orbitals are easier to draw than the more

accurate picture shown in Figure 1.10.

For the first time, we begin to get hints of the causes of the complicated three-

dimensional structures of molecules: Electrons are the “glue” that holds the atoms

of molecules together, and electrons are confined to regions of space that are by no

means always spherically symmetrical.

As Figure 1.12 shows, we can now make quite detailed pictures of the electrons

in atoms. The 1s orbitals have been omitted in the atoms past He. The other elec-

trons are shown as dots.

The idea of covalent bonding was largely the creation of the American chemist

Gilbert Newton Lewis (1875–1946), and the molecules formed by covalent bonds

are usually written as what are called Lewis structures or Lewis dot structures. In

almost all covalently bonded molecules, every atom can achieve a noble gas electron-

ic configuration by sharing electrons. In the H

2

molecule,each hydrogen atom shares

two electrons and thus resembles the noble gas helium (Fig. 1.14). In each fluo-

rine has a pair of electrons in the lowest-energy 1s orbital and eight other electrons

in n 2 orbitals, six unshared (called either nonbonding electrons or lone-pair

electrons) and two shared in the fluorine–fluorine bond as shown in Figure 1.14.

Thus, each fluorine in F

2

has a filled octet and,by virtue of sharing electrons, resem-

bles the noble gas neon. The Lewis dot structure of HF in Figure 1.14 shows that

the hydrogen is helium-like and the fluorine is neon-like.

F

2

,

14 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

Each hydrogen has a

share in two electrons

and is helium-like

One

electron

each

1

H

==

HH H H H

2

..

+

H

.

H

.

==

F

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

FF

2

..

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

.

F

..

.

..

..

+

H

..

F

..

..

..

=

HF

..

..

..

H

.

+

F

..

.

..

..

Electron count

2 1s (not shown)

6 Nonbonding

2 Shared

10 Neon-like

1

H

1 Nonbonding

9

F

2 1s (not shown)

7 Nonbonding

9

Electron count

1

H

2 Shared

2 Helium-like

9

F

2 1s (not shown)

6 Nonbonding

2 Shared

10 Neon-like

Electron count

Electron count

2 1s (not shown)

7 Nonbonding

9

9

F

FIGURE 1.14 Lewis dot structures for

and HF. Every atom has a

noble gas electronic configuration.

F

2

,H

2

,

With the exception of H, electrons in 1s orbitals are not involved in bonding

and therefore are not shown in Lewis structures. Anytime you need to count elec-

trons in one of these structures, you have to remember to account for the unshown

1s electrons.

Hydrogen fluoride is different from any of the molecules mentioned so far in

that the two electrons in the bond are shared unequally between the two atoms. In

any diatomic molecule made from two different atoms, there cannot be equal shar-

ing of the electrons because one atom must attract the electrons more strongly than

the other atom does.Covalent bonds in which the two electrons are shared unequal-

ly are polar covalent bonds.Because electrons carry a negative charge,the atom bear-

ing the larger share of electrons carries a partial negative charge,and the atom bearing

the lesser share of electrons has a partial positive charge. Any molecule in which elec-

trical charge is separated in this way has a dipole moment, which is a measurement

of the polarity of a bond. Dipole literally means two poles. Often a small arrow point-

ing from positive to negative is used to indicate the direction of the dipole, or δ

+

1.3 Covalent Bonds and Lewis Structures 15

(partial positive charge) and (partial negative charge) signs are placed on the

appropriate atoms (Fig.1.15).The dipole moment is measured in debye units named

after the Dutch physicist and chemist Petrus Josephus Wilhelmus Debye

(1884–1966), who spent much of his working life at Cornell University and won

the Nobel prize in Chemistry in 1936.

The tendency of an atom to attract electrons is called electronegativity.Atoms

with high electron affinities are the most electronegative and are found at the right

of the periodic table (Table 1.8). Atoms with low electronegativities and low ion-

ization potentials are called electropositive and lie at the left of the table.The extreme

case for unequal electron sharing is the ionic bonding seen in Na

F

and K

Cl

.

δ

-

δ

+

δ

–

AA

AB

AB

Two identical atoms share the electrons in a covalent bond

equally: examples are H

H and F

F

Two different atoms cannot share the electrons in a covalent

bond equally. One atom will attract the electrons more

strongly than the other. This bond is a polar covalent bond

Here B attracts the electrons more strongly than A. The

direction of the dipole is shown with a plus sign at the

positive end of the arrow, with the symbols

δ

+

and δ

–

added to show the partial charges

FIGURE 1.15 Comparison of covalent

and polar covalent bonds.

TABLE 1.8 Some Electronegativities

H

2.3

Li

0.9

Na

0.9

K

0.7

Rb

0.7

Be

1.6

Mg

1.3

B

2.1

Al

1.6

C

2.5

Si

1.9

N

3.1

P

2.3

O

3.6

S

2.6

F

4.2

Cl

2.9

Br

2.7

I

2.4

2

(IIA)

3

(IIIA)

4

(IVA)

5

(VA)

6

(VIA)

7

(VIIA)

1

(IA)

PROBLEM 1.4 Show the direction of the dipole in the indicated bonds of the

following molecules:

Not all molecules containing polar covalent bonds have dipole moments. Many

do, including all those shown in Problem 1.4; but consider carbon dioxide (CO

2

), a

linear molecule of the structure (the double lines represent double

bonds in which the carbon atom shares two pairs of electrons with each oxygen

atom). Because oxygen is more electronegative than carbon (Table 1.8), both bonds

O

P

C

P

O

H

O

Cl, H

O

F, Li

O

F, H

3

C

O

Cl, HO

O

Br, Br

O

Cl

Carbon dioxide

COO

FIGURE 1.16 Carbon dioxide has no

dipole moment.

in CO

2

are polar, as shown in Figure 1.16.Even though carbon dioxide contains these

two polar bonds, however, there is no net dipole moment in the molecule because

the bond dipoles cancel. The dipole moment of a molecule is the vector sum of all

dipoles in the molecule.In the two dipoles are equal in magnitude and

pointed in exactly opposite directions; they cancel. There are two polar carbon–

oxygen bonds in carbon dioxide, but no dipole moment.

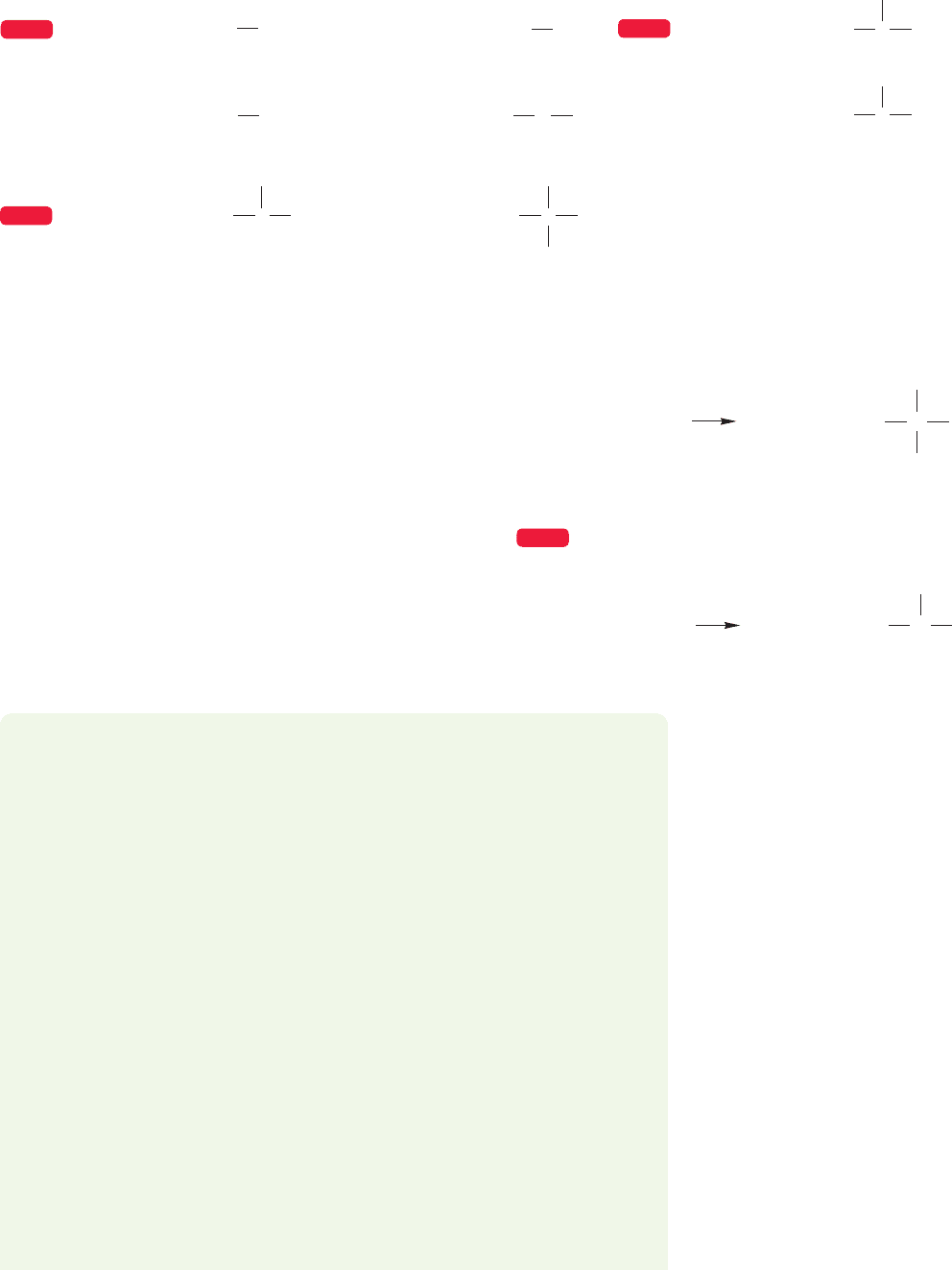

In representing three-dimensional structures on a two-dimensional surface such as

a chalkboard or book page,it is necessary to devise some scheme for showing bonds

directed away from the surface, either toward the front (up and out of the board or

page) or toward the rear (down and into the board or page). In the figure for

Problem 1.5, and in many, many future figures, the solid wedges ( ) represent

covalent bonds that are coming out toward you and the dashed wedges ( ) repre-

sent covalent bonds that are retreating into the page.

O

P

C

P

O,

16 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

=

C

Cl

Cl

Cl

Cl

C

Carbon tetrachloride

(CCl

4

)

Chloroform

(CHCl

3

)

C

Cl

Cl

Cl

Cl

=

C

H

Cl

Cl

Cl

H

Cl

Cl

Cl

WEB 3DWEB 3D

7

7

This icon means that you can find the calculated three-dimensional structure of the molecule on the Web

at www.wwnorton.com/studyspace. That structure can be manipulated so that you can view it from any

direction,and changed so that you can see different versions of it (space filling,ball-and-stick, and so on).The

structures can also be interrogated; they will tell you bond lengths and interatomic angles, if asked. You will

also find comments, problems, and answers related to the molecule on the Web site.

CONVENTION ALERT

In order to write Lewis dot structures for molecules containing only hydrogen

and second row atoms (most organic molecules), we need to know the number of

electrons in the atoms. For atoms in the second row of the periodic table, we can

tell immediately how many electrons are available for bonding by knowing the atom-

ic number of the atom or by knowing the column the atom is in. The number of

available electrons is equal to the total number of electrons in the atom, which is

the same as the atomic number, less the two 1s electrons. One can also use the col-

umn number, which corresponds to the number of electrons in the outer shell (see

Table 1.8).The electrons in the outermost shell, which are the least tightly held elec-

trons, are called the valence electrons.

For atoms in the third row of the periodic table, neither the two 1s electrons nor

the eight electrons in the second shell are shown in the Lewis structure.

Instead, only the valence electrons in the third shell appear.

In complete Lewis structures,every valence electron is written as a dot. In anoth-

er form of a Lewis structure, pairs of electrons forming covalent bonds are shown

as lines and only the nonbonding valence electrons appear as dots. We will use this

kind of Lewis structure throughout this text.Some examples of Lewis structures are

12s

2

2p

6

2

PROBLEM 1.5 Which of these two molecules has a dipole moment and which

does not? Look carefully at the shapes of the two tetrahedral molecules.The blue

dashed lines show the outlines of a tetrahedron. If visualizing the three-

dimensional aspects of these molecules is hard for you at first, by all means use

molecular models.

1.3 Covalent Bonds and Lewis Structures 17

OHHHH

..

..

..

O

..

..

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

..

H

2

O

H

2

HHHHor

..

BH

3

NH

3

CH

4

HH H HB

H

HHN

H

HHC

H

H

or

or

or

F

2

or

HH

..

F

..

..

..

F

..

..

..

HF or

or

B

H

..

..

..

..

..

H

H

N

H

PCl

3

Cl ClP

or

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

Cl

Cl

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

Cl

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

P

..

..

..

..

HH

C

H

H

WEB 3D

WEB 3D

WEB 3D

FIGURE 1.17 A few Lewis dot

structures.

FIGURE 1.18 Construction of a Lewis

structure for (a) methane, and

(b) ammonia, NH

3

.

CH

4

,

shown in Figure 1.17 Another variation of the Lewis structure uses a

line to represent the nonbonding electrons. We will not use this repre-

sentation because the line can be easily confused with a negative charge.

Let’s draw Lewis structures for methane and ammonia (Fig.1.18).

To construct the Lewis dot structure of methane (CH

4

),we first deter-

mine that carbon has four valence electrons for bonding.Carbon

has a total of six electrons, but two are in the unused 1s orbital. Note

that carbon is in column 4 of the periodic table. Each hydrogen con-

tributes one electron. Thus, four two-electron covalent bonds

are formed,with no electrons left over (Fig. 1.18a). For ammo-

nia nitrogen contributes five electrons (seven

minus the 1s pair; nitrogen is in column 5), and the three

hydrogens contribute one electron each.Therefore, three two-

electron nitrogen–hydrogen bonds are formed, each contain-

ing one electron from N and one from H, and there is a

nonbonding pair left over (Fig. 1.18b).

(

7

N)(

:

NH

3

),

(

6

C)

WORKED PROBLEM 1.6 Construct Lewis structures for the following neutral

molecules:

*(a) BF

3

(b) H

2

Be (c) BH

3

(d) ClCH

3

(e) HOCH

3

(f)

ANSWER (a) The first task is to determine the gross structure of Is it

or some other structure containing fluorine–fluorine bonds, or a

structure containing only boron–fluorine bonds? We start by working out the

number of electrons available for bonding. Fluorine has seven valence elec-

trons available for bonding (9 2 1s, or fluorine is in column 7) and thus has a

single unpaired, or “odd” electron. Boron has three valence electrons (5 2

1s, or boron is in column 3).

Notice that boron has three electrons available for bonding and a structure with

three boron–fluorine bonds can be nicely accommodated. There is no easy way to

form a molecule containing both boron–fluorine and fluorine–fluorine bonds.

9

F

1s

2

2s

2

2p

x

2

2p

y

2

2p

z

5

B

1s

2

2s

2

2p

F

..

..

..

.

There are seven electrons

available for bonding

There are three electrons

available for bonding

.

.

B

.

(

5

B)

(

9

F)

B

O

F

O

F

O

F,

BF

3

.

H

2

N

O

NH

2

6

C contributes four electrons to bonding;

each

1

H contributes one electron

CH

4

(b)

.

.

..

.

=

HH

H

N

.

.

.

HH

H

HH

H

N

..

..

..

..

N

..

7

N contributes five electrons to bonding;

each

1

H contributes one electron

NH

3

WEB 3D

.

.

.

.

=

HH

H

H

C

.

.

.

.

HH

H

H

HH

H

H

C

..

..

..

..

C

(a)

(continued)

WEB 3D

.

.

.

.

=

Four valence electrons each

C

.

.

.

.

.

.

C

.

.

.

H

H

C

.

C

6

C

One electron each

1

H

CC

A double bond

Ethene

(Ethylene)

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

18 CHAPTER 1 Atoms and Molecules; Orbitals and Bonding

FIGURE 1.19 Construction of a

Lewis structure for ethane.

A structure with covalent bonds in which the seventh electron on each fluorine is

shared with one of boron’s available three electrons gives the correct answer:

F

..

..

..

F

F

..

..

..

..

..

..

=

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

..

..

B

F

..

..

..

F

F

B

F

..

..

..

F

F

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

..

B

Single bonds such as the ones shown in Figures 1.17 and 1.18 are not the only

kind of covalent bonds. Atoms of elements below the first row of the periodic table

can form double and triple bonds, as we saw earlier when we looked at the covalent

bonds in carbon dioxide.Usually, the structural formula will give you a clue when mul-

tiple bonding is necessary.For example, ethane (H

3

CCH

3

) requires no multiple bonds;

indeed it permits none, as can be seen from construction of the Lewis structure

(Fig 1.19).Each carbon is attached to four other atoms—all four of the valence electrons

in each carbon are shared in single bonds to the three hydrogen atoms and the other

carbon.Therefore all electrons can be accounted for in single bonds between the atoms.

WEB 3D

C

.

.

.

.

=

H

H

Four valence electrons each

H

C

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

H

H

C

.

H

.

.

..

..

..

..

C

..

..

..

HH

H

H

H

H

6

C

One electron each

Ethane

1

H

HH

H

H

C

H

H

C

=

Four valence electrons each

6

C

One electron each

1

H

A triple bond

C

.

.

.

.

C

.

.

.

.

H

.

H

.

C

.

.

C

.

.

HHCCHH

Ethyne

(Acetylene)

WEB 3D

FIGURE 1.21 Construction of a

Lewis structure for ethyne

(acetylene).

FIGURE 1.20 Construction of a

Lewis structure for ethene (ethylene).

In the molecule known as ethene or ethylene (H

2

CCH

2

), only three of carbon’s

four bonding electrons are used up in forming single covalent bonds to two hydro-

gens and the other carbon (Fig. 1.20). There is an unbonded electron remaining on

each carbon, and these two electrons are shared in a second carbon–carbon bond.

Thus, ethylene contains a carbon–carbon double bond.

In ethyne or acetylene (HCCH), shown in Figure 1.21, two of the four bond-

ing electrons in each carbon are used in forming single bonds to one hydrogen and

the other carbon. Two electrons are left over on each carbon, and these are shared

to create a triple bond between the carbons.